文章信息

- 管理, 郝碧波, 刘天俐, 程绮瑾, 叶兆辉, 朱廷劭. 2014.

- Guan Li, Hao Bibo, Liu Tianli, Cheng Qijin, Yip Paul Siu Fai, Zhu Tingshao. 2014.

- 新浪微博用户中自杀死亡和无自杀意念者特征差异的研究

- A pilot study of differences in behavioral and linguistic characteristics between Sina suicide microblog users and Sina microblog users without suicide idea

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2015, 36(5): 421-425

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2015, 36(5): 421-425

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2015.05.003

-

文章历史

- 投稿日期:2014-11-14

2. 中国科学院大学;

3. 北京大学人口研究所;

4. 香港大学香港赛马会防止自杀研究中心

2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences;

3. Institute of Population Research, Peking University;

4. Hong Kong Jockey Club Center for Suicide Research and Prevention, the University of Hong Kong

自杀是一种严重的心理健康问题。2014年我国城市居民自杀年死亡率为4.82/10万,农村居民则高达8.58/10万[1]。传统自杀风险评估研究主要采用心理测验、访谈和问卷等[2],其成本耗费较大。研究表明,尽管自杀死亡的个体生前很少主动寻求帮助,但在日常言语表达中往往有所流露自杀意念[3, 4]。近年来微博成为社交网络用户具有时效性自我表达的途径之一,因其具有开放可见性,部分学者已关注通过该平台开展自杀相关研究[5, 6, 7]。不论是线上或者线下,语言能够显露出个体身份和社会关系等重要信息[8, 9]。近年来国内外学者在心理健康评估中使用网络社交媒体的文本分析方法已取得一些成果[10, 11, 12, 13, 14]。但由于网络的匿名特性和研究自杀本身的困难[2],总体而言该方法对自杀风险评估和预警仍处在初级阶段,目前尚无有效在线评估用户个体自杀意念和自杀未遂的研究报道。为此本研究在新浪微博平台上探讨自杀死亡用户的微博行为和语言模式,比较网络识别自杀死亡用户和无自杀意念用户的行为和文本特征差异,为在社交媒体平台开展自杀干预提供思路和数据支持。 对象与方法

1. 研究对象:自杀死亡用户样本来自社交网络。通过媒体报道,了解并联络新浪微博认证用户“逝者如斯夫dead”,在其协助下获得被描述为自杀死亡的微博用户账号。在每个疑似自杀死亡账号的微博主页中,从至少3名被该账号关注的微博用户留言中再次确认该账号所有者确系死于自杀。2014年2-5月共收集网络识别自杀死亡新浪微博用户账号35个,从中剔除外国籍1人,ID由经纪人代理1人,认证名1人,以及原创微博数过少(<20条)1人,最终用于分析的网络识别自杀死亡(自杀死亡组)31人(男性12人,女性19人)。

采用3个量表筛选无自杀意念微博用户(对照组)。①贝克自杀意念量表(Scale for Suicide Ideation,SSI)[15]共19个项目,如果用户做到项目5则可通过,且总分越低自杀意念越低;②自杀可能性量表中文版(Suicide Possibility Scale,SPS)[16]共36个项目,分数越高其自杀风险越大,本研究按刘国华和张桂英[17]的筛选标准(<50分);③抑郁自评量表(Self-rating Depression Scale,SDS)[18]共20个项目,分数越高抑郁倾向越大,如<53分则通过。在知情同意下,于2014年5月共向1 500名新浪微博用户发放问卷,回收1 385份,筛选出无自杀意念用户91人,其中保留发布公开微博数>100条者52人,为避免“试验者效应”,从中剔除22名与作者有社交关系的用户,最终确认符合对照组标准的新浪微博活跃用户30人(男15人,女15人)。

本研究通过新浪微博数据开放平台,应用程序编程接口经伦理许可的方法,完成两组用户自注册起至2014年10月8日所有公开可见的微博数据,并获得中国科学院心理研究所伦理委员会的审查批准。

2. 研究方法:

(1)行为特征提取:微博用户行为特征主要体现在自我表达的特点、与其他用户的互动,以及活跃周期等,共提取10类用户行为数据(表 1)。由于自杀死亡组不再有更新,而对照组一直处于活跃状态,为了排除时间因素对用户微博特征值的影响,行为特征指标大多使用比率数据,或平均每篇微博所含特征计数值。行为特征值的提取和计算由计算机程序完成。

(2)语言特征提取:本研究使用中文版LIWC (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count)词库[19, 20, 21],涉及词类包括总体描述词、语言过程词、心理过程词、个人关切词等共计88类(图 1),并由中国科学院心理研究所计算机网络心理实验室研发的“文心中文心理分析系统”完成语言特征的提取,即由计算机程序从每名用户的微博文本中自动输出88类语言特征,计算每一种类别的词语使用频率百分数值。

|

| 图 1 简体中文LIWC词典词类特征 |

3. 统计学分析:使用SPSS 17.0软件。首先对特征值分布进行Kolmogorov-Smirnov(K-S)正态性检验,对于符合正态分布的行为和语言特征,两组之间的差异使用独立样本t检验;对于不符合正态分布的行为和语言特征,两组之间的差异使用Mann-Whitney U秩和检验。

1. 一般特征:自杀死亡组生前公开发表微博数M=316.0 [四分位间距(QR)=1 216.0],平均活跃天数为(198.0±162.2)d;对照组公开发表微博数M=932.0(QR=915.8),平均活跃天数为(471.5±197.3)d。表明两组在生前或现阶段均较深程度使用微博,并有一定的网络社交水平。

2. 组间差异分析:

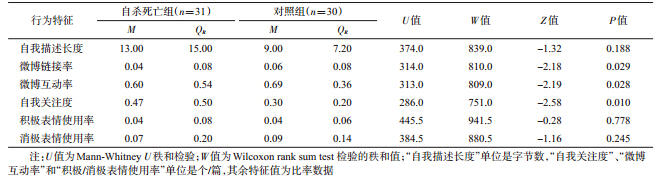

(1)微博行为特征:K-S正态性检验结果表明,10种行为特征中有“微博原创率”、“集体关注度”、“夜间活跃度”和“社交活跃度”4个特征服从正态分布(P<0.05)。对这些特征采用独立样本t检验显示,自杀死亡组和对照组在“社交活跃度”特征上的差异有统计学意义(表 2)。其他行为特征进行Mann-Whitney U秩和检验,结果表明,自杀死亡组的“微博链接率”、“微博互动率”和“自我关注度”与对照组的差异有统计学意义(表 3)。

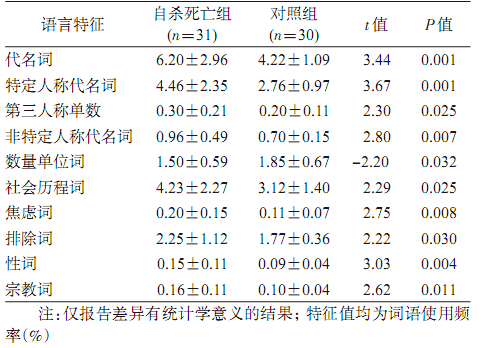

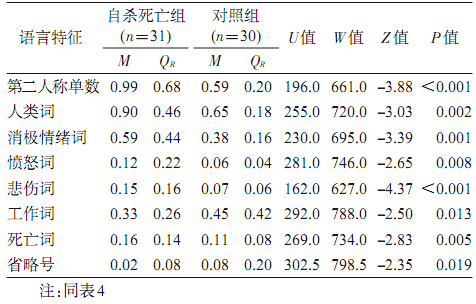

(2)微博语言特征:采用K-S正态性检验,88种语言特征中有61类特征值服从正态分布(P>0.05)。独立样本t检验显示,自杀死亡组和对照组在“代名词”(如他、你们、在下)、“特定人称代名词”(如你、在下、他们)、“第三人称单数”(如他、她)、“非特定人称代名词”(如一切、这些、其他)、“数量单位词”(如条、头、只)、“社会历程词”(如家人、接纳、打招呼)、“焦虑词”(如不安、挣扎、紧绷)、“排除词”(如取消、但是、除外)、“性词”(如上床、性欲、裸体)和“宗教词”(如上帝、慈悲、信仰)特征值的差异有统计学意义(表 4)。其他语言特征进行Mann-Whitney U秩和检验。结果表明,自杀死亡组在“第二人称单数”(如你、您)、“人类词”(如人民、成员、群众)、“消极情绪词”(如担忧、猜疑、嫉妒)、“愤怒词”(如可恶、抱怨、破坏)、“悲伤词”(如心痛、沮丧、无力)、“工作词”(如工厂、面试、薪水)、“死亡词”(如亡故、自杀、遗嘱)和“省略号”(…)的使用频率上与对照组的差异有统计学意义(表 5)。

本研究显示,自杀死亡组比对照组自我关注程度更强,链接到他人微博的频率更低,微博中和其他用户的互动也更少。结果表明,有自杀意念的个体可能更关注于自身[22],这与以往大量研究结果一致[14, 23, 24]。研究中还发现自杀死亡组与对照组相比有更多的负面表达。如自杀死亡组在情感方面使用了更多的消极情绪词以及更为具体的类别,包括焦虑、愤怒、悲伤;在功能词方面使用了更多表达排除的词语;在个人关切方面使用更多表达死亡的词语,包括与自杀直接相关的词汇。已有的研究更多关注自杀死亡者或高自杀风险者表达的消极情感[23, 25, 26],有自杀意念的个体在文本中更多使用死亡意象[23]。

本研究显示在宗教词的使用频率上自杀死亡组高于对照组。以往研究表明皈依宗教信仰是应对个体内心极端冲突的一种方式[27],自杀死亡的个体有可能采取该方式。研究还显示,工作词的使用频率自杀死亡组低于对照组。以往有研究认为存在心理健康问题(如抑郁症)的个体,其工作积极性及其业务绩效均可受负面影响[28]。此外,自杀死亡组在多种人称和非人称代词、社会历程词、性词、人类词的使用频率高于对照组,数量词、省略号的使用频率低于对照组,但此结论目前尚无理论依据支持,这些词语类别特征上的差异可能与我国文化语言表达特点相关,值得进一步探讨。

本研究存在局限性。首先获得自杀死亡组的样本信息极为困难。收集网络自杀死亡用户账号主要依赖社交网络媒体报导,与传统研究相比其样本量偏小,且由于网络匿名的特征,现阶段难以大规模开展收集和确认工作,故本研究抽样时未对自杀死亡组和对照组的多种人口统计学信息进行控制存在偏倚。此外国内外目前还无网络自杀特征的评估体系,尽管本研究在预实验中采取了一些避免结果偏倚的措施,如筛选自杀死亡组和对照组要求具有一定数目的公开发表微博,但仍可能难以严格意义上区分微博用户的“行为特征”和“语言特征”;且目前使用的计算机语言特征提取工具还缺乏对每个特征类别明确的定义。

总之,本研究提示在网络微博上自杀死亡用户确实存在特定行为表现以及语言表达,并与无自杀意念的一般用户存在差异。

| [1] Center of Health Statistics and Information, Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China. China Public Health Statistical Yearbook 2013[R/OL]. (2014-04-26) [2014-07-21]. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/htmlfiles/zwgkzt/ptjnj/year2013/index2013.html. (in Chinese) 中华人民共和国卫生部统计信息中心. 2013中国卫生统计年鉴[R/OL]. (2014-04-26) [2014-07-21]. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/htmlfiles/zwgkzt/ptjnj/year2013/index2013.html. |

| [2] Li GY. Suicide and self-harm[M]. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2009:17-22. (in Chinese) [3] Jiang GR, Xia M. Psychological help-seeking:current research and the phases-decision-making model[J]. Adv Psychol Sci, 2006, 14(6):888-894. (in Chinese) 江光荣, 夏勉. 心理求助行为:研究现状及阶段-决策模型[J]. 心理科学进展, 2006, 14(6):888-894. |

| [4] Ray LY, Johnson N. Adolescent suicide[J]. Person Guid J, 1983, 62(3):131-135. |

| [5] Silenzio VMB, Duberstein PR, Tang W, et al. Connecting the invisible dots:Reaching lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents and young adults at risk for suicide through online social networks[J]. Soc Sci Med, 2009, 69(3):469-474. |

| [6] Fu KW, Cheng QJ, Wong PWC, et al. Responses to a self- presented suicide attempt in social media:A social network analysis[J]. Crisis, 2013, 34(6):406-412. |

| [7] Ruder TD, Hatch GM, Ampanozi G, et al. Suicide announcement on Facebook[J]. Crisis, 2011, 32(5):280-282. |

| [8] Tausczik YR, Pennebaker JW. The psychological meaning of words:LIWC and computerized text analysis methods[J]. J Lang Soc Psychol, 2010, 29(1):24-54. |

| [9] Barak A, Miron O. Writing characteristics of suicidal people on the internet:a psychological investigation of emerging social environments[J]. Suicide Life-Threat Behav, 2005, 35(5):507-524. |

| [10] Pestian J, Nasrallah H, Matykiewicz P, et al. Suicide note classification using natural language processing:a content analysis[J]. Biomed Inform Insights, 2010, 2010(3):19-28. |

| [11] Jashinsky J, Burton SH, Hanson CL, et al. Tracking suicide risk factors through Twitter in the US[J]. Crisis, 2014, 35(1):51-59. |

| [12] Zhang JW. Research on emotion recognition technology of microblog based on psychological prewarning model[D]. Hefei:Hefei University of Technology, 2013. (in Chinese) 张金伟. 微博情感分析的心理预警模型与识别研究[D]. 合肥:合肥工业大学, 2013. |

| [13] Li L. Internet suicide notes recognition research[D]. Wuhan:Central China Normal University, 2012. (in Chinese) 李隆. 网络文本自杀倾向性识别方法研究[D]. 武汉:华中师范大学, 2012. |

| [14] Wang XY, Zhang CH, Ji Y, et al. A depression detection model based on sentiment analysis in micro-blog social network[M]. Trends and Applications in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. Berlin Heidelberg:Springer, 2013:201-213. |

| [15] Li XY, Phillips MR, Tong YS, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of Beck Suicide Ideation Scale (BSI-CV) in adult community residents[J]. Chin Mental Health J, 2010, 24(4):250-255. (in Chinese) 李献云, 费立鹏, 童永胜, 等. Beck 自杀意念量表中文版在社区成年人群中应用的信效度[J]. 中国心理卫生杂志, 2010, 24(4):250-255. |

| [16] Liang YN, Yang LZ. Study on reliability and validity of the Suicide Probability Scale[J]. Chin J Health Psychol, 2010, 18(2):225-227. (in Chinese) 梁瑛楠, 杨丽珠. 自杀可能性量表的信效度研究[J]. 中国健康心理学杂志, 2010, 18(2):225-227. |

| [17] Liu GH, Zhang GY. Gender differences of the undergraduates' suicide probability[J]. Chin J Sch Health, 2012, 33(10):1198- 1200. (in Chinese) 刘国华, 张桂英. 大学生自杀可能性的性别比较[J]. 中国学校卫生, 2012, 33(10):1198-1200. |

| [18] Shu L. Self-rating depression scale[J]. Chin Mental Health J, 1999, Suppl:S194-196. (in Chinese) 舒良. 抑郁自评量表 (SDS)[J]. 中国心理卫生杂志, 1999, 增刊:194-196. |

| [19] Pennebaker JW, Francis ME, Booth RJ. Linguistic inquiry and word count:LIWC 2001[J]. Mahway:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2001, 71:2001. |

| [20] Pennebaker JW, Mehl MR, Niederhoffer KG. Psychological aspects of natural language use:Our words, our selves[J]. Annu Rev Psychol, 2003, 54(1):547-577. |

| [21] Gao R, Hao BB, Li H, et al. Developing simplified Chinese psychological linguistic analysis dictionary for microblog[M]. Berlin Heidelberg:Springer, 2013:359-368. |

| [22] Psych MWD, Sedway J, Bulik CM, et al. Linguistic analyses of natural written language:Unobtrusive assessment of cognitive style in eating disorders[J]. Int J Eat Disord, 2007, 40(8):711-717. |

| [23] Li TM, Chau M, Yip PSF, et al. Temporal and computerized psycholinguistic analysis of the blog of a Chinese adolescent suicide[J]. Crisis, 2014, 35(3):168-175. |

| [24] Stirman SW, Pennebaker JW. Word use in the poetry of suicidal and nonsuicidal poets[J]. Psychosom Med, 2001, 63(4):517-522. |

| [25] Li TM, Chau M, Wong PW, et al. A hybrid system for online detection of emotional distress[M]. Berlin Heidelberg:Springer, 2012:73-80. |

| [26] Pestian JP, Matykiewicz P, Linn-Gust M, et al. Sentiment analysis of suicide notes:A shared task[J]. Biomed Inform Insights, 2012, 5 Suppl 1:3-16. |

| [27] Pienaar J, Rothmann S, van De Vijver FJR. Occupational stress, personality traits, coping strategies, and suicide ideation in the South African Police Service[J]. CJB, 2007, 34(2):246-258. |

| [28] Lerner DMS, Henke RM. What does research tell us about depression, job performance, and work productivity?[J]. J Occup Environ Med, 2008, 50(4):401-410. |

2015, Vol. 36

2015, Vol. 36