b Collaborative Innovation Center of Henan Province for Green Manufacturing of Fine Chemicals, Key Laboratory of Green Chemical Media and Reactions, Ministry of Education, School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Henan Normal University, Xinxiang 453007, China

Chiral ligands play a major role in the tuning of reactivity and enantioselectivity in asymmetric transition-metal catalysis, which renders the efficient synthesis of chiral scaffolds with biological and economical significances. Quinap (Ⅰ, Scheme 1a) has become an useful subclass of atropisomeric N,P-ligand since discovered by Brown in 1993 [1], displaying distinctive stereocontrol in several enantioselective reactions, such as hydroboration, diboration, allylic alkylation, cycloaddition, A3 coupling and others [2,3]. The original synthesis of enantioenriched Quinap was developed by Brown through chemical resolution using stoichiometrically chiral palladium complexes (Scheme 1b) [1]. After that, chiral sulfoxide auxiliary strategy [4–6], Pd-catalyzed dynamic kinetic phosphination of Quinol [7,8] and atroposelective nitrogen-oxidation protocol [9] were successfully demonstrated to obtain optically active Quinap. Probably because of the absence of a general method to prepare isoquinoline-ring modified Quinap analogs, Guiry, Carreira, Aponich and Ma replaced the isoquinoline unit of Quinap by more accessible azaheterocycles to generate valuable chiral ligands (Scheme 1a), such as Quinazolinap Ⅱ [10,11], Pinap Ⅲ [12,13], StackPhos Ⅳ [14,15], UCDPhim/StackPhim Ⅴ [16,17], and Pyrinap Ⅵ [18]. The additional nitrogen atom made ligands Ⅱ–Ⅵ easily to be modified and allowed their facile array syntheses for the screening in a variety of enantioselective transformations [2,3,10–18]. Despite of these significant achievements on the development of N,P-ligand, to our knowledge, isoquinoline ring-substituted Quinap derivatives bearing structural and electronic modifications are still ignored so far [19]. Because the donor nitrogen in ligands Ⅱ, Ⅲ and Ⅵ are substantially less basic than Quinap, their behaviors in catalytic asymmetric reactions could be different. Therefore, the utilizing Quinap analogs as chiral ligands is far from being studied in depth and breadth, and it is highly desirable to identify the relationship between steric and electronic effects on the isoquinoline ring of Quinaps with their enantioselectivity profiles.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Motivation and the design for Quinap oxides synthesis. | |

Isocyanides are valuable building blocks for the preparation of heterocycles due to their unique and versatile reactivities [20–23]. In this context, palladium-catalyzed imidoylative cyclization of isocyanides becomes a robust approach in the synthesis of a range of nitrogen-containing frameworks [24]. Great contributions have been devoted by the research groups of Takemoto [25], Ji [26], Zhu [27–30], Pal [31], etc., and a variety of azaheterocycles such as indoles [25], 1H-isoindoles [27], 4-aminoquinazolines [26], phenanthridines [28], isoquinolines [28], β-carbolines [29], dibenzoox(di)azepines [30], indoloquinolines [31] and indoloindolones [32] have been successfully assembled. Notably, the enantioselective version of this transformation was recently realized by Zhu and co-workers for the preparation of chiral 3,4-dihydroisoquinolines [33], pyridoferrocenes [34], 2‑arylquinazolinones [35] and pyridohelicenes [36]. During the course of our continuous interests on the heterocyclization of functionalized isocyanides [37–43], we herein present a palladium-catalyzed imidoylative cyclization of arylethenyl isocyanides with 2-diphenylphosphinyl-1-naphthyl bromides, which provides an efficient and practical protocol for the facile synthesis of various isoquinoline ring-modified Quinap phosphine oxide derivatives in good to excellent yields (Scheme 1c). This reaction tolerates many functional groups and renders Quinap derivatives with substitution patterns not obtained using coupling reactions. The potential applications of the resulting chiral N,P-ligands L7 and L12 were demonstrated by a copper-catalyzed enantioselective A3-coupling reaction and alkynylation of quinolines.

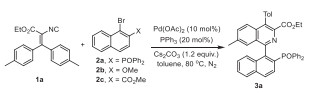

Initially, diaryl substituted vinylisocyanide 1a and 2-diphenylphosphinyl-1-naphthyl bromide 2a were selected as model substrates (Table 1). Luckily, the desired Quinap oxide (Quinapo) 3a was obtained in 93% yield, catalyzed by the established Pd(OAc)2/PPh3 system [27–31] in the presence of Cs2CO3 as a base in toluene at 80 ℃ for 1 h (Table 1, entry 1). The configuration of 3a was confirmed by X-ray diffraction analysis (CCDC: 2367492). It was found that the time for syringe pump addition of the solution of 1a to the reaction mixture is crucial to the product yield (Table 1, entry 1 vs. 2 and 3). When the time was shortened to 0.5 h, the yield of 3a dropped to 75% (Table 1, entry 2) and the time for 0.1 h caused that only trace amount of 3a could be detected (Table 1, entry 3). To our delight, the transformation is rather practical for both 0.5 and 10 mmol scale reactions, affording 3a in excellent yields (Table 1, entries 4 and 5). Notably, when the diphenylphosphinyl in substrate 2a was replaced by methoxyl or methoxycarbonyl groups (2b and 2c), the corresponding products 1-(2-methoxynaphthalen-1-yl)−4-(p-tolyl)isoquinoline-3-carboxylate 3a' or 1-(2-(methoxycarbonyl)-naphthalen-1-yl)−4-(p-tolyl)isoquinoline-3-carboxylate 3a'' could not be detected under the standard conditions (Table 1, entries 6 and 7). These results indicated that the diphenylphosphinyl plays a vital role in this palladium-catalyzed imidoylative cyclization.

|

|

Table 1 Optimization of reaction conditions.a |

After establishing the optimal reaction conditions, we began to explore the scope of both the vinyl isocyanides 1 and 2-diarylphosphinyl-1-naphthyl bromides 2. As displayed in Scheme 2, a wide range of Quinapo derivatives 3a-x were obtained by this palladium-catalyzed imidoylative cyclization. The reaction tolerates a series of diaryl substituted vinyl isocyanides 1, and Quinapos 3a-f bearing both electron-rich, -neutral and -poor aryl at 4-position and electron-donating as well as -withdrawing groups at 7-position were produced in high to excellent (71%−98%) yield. Besides the ester group, amide groups could be easily installed at the 3-position of isoquinoline ring (3g-3k). 4-Unsubstituted 5-Me/7-MeO-Quinapos 3l and 3m were generated in low yields, whereas 6,8-Me2-Quinapo 3n was given in 94% yield. Dibenzo fused Quinapo 3o could also be obtained albeit in low yield. A mixture of (Z)- and (E)−2-isocyano-3-phenyl-3-(p-tolyl)acrylate 1p and 1p' (ratio 1:1.2) was treated with the standard condition, 3p and 3p' were furnished as a mixture (ratio 1:1.2), indicating that only the aryl cis to isocyno group on the vinyl isocyanide occurs cyclization to form isoquinoline ring. Next, the palladium-catalyzed imidoylative cyclization of isocyanide 1a with several phosphine oxides 2 was tested. The benzene ring of diarylphosphine oxides 2 substituted with 4-methyl, 4-methoxyl, 4-chloride, steric-hindered 3,5-dimethyl and ditertbutyl groups were investigated, delivering the desired products 3q–3u in good to excellent yields. Naphthyl-phosphine oxides afforded the desired product 3v in 73% yields. Diethyl phosphonate was also proven to be the suitable substrate to afford the corresponding product 3w in 83% yield. Additionally, the phosphine oxides with a bromide substituted at nathphyl ring was feasible in this reaction to give the bromo Quinapo 3x in 69% yield. Notably, 2‑bromo-3-methylphenyl-substituted diphenylphosphine oxide resulted the corresponding product 3y in excellent yield.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Synthesis of Quinapo derivatives 3. Reaction conditions: 1 (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv., in 10 mL of toluene), 2 (0.75 mmol, 1.5 equiv., in the same amount of toluene), Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%), PPh3 (20 mol%), Cs2CO3 (1.2 equiv.), 80 ℃, N2, syringe pump addition of the solution of 1 within 3 h Isolated yields of 3. | |

On the basis of the present results and literature precedent [27–31], a plausible mechanistic pathway is proposed in Scheme 3 (exemplified by the reaction of 1a with 2a). First, oxidative addition of aryl bromide 2a with Pd(0) and coordination with the diphenylphosphine oxide group [44] produce a five-membered Pd(Ⅱ) intermediate A. Next, coordination and migratory insertion of isocyano group in 1a into C-Pd bond of A affords imidoyl palladium B. Then, activation of the C(sp2)-H bond of intermediate B gives a seven-membered palladacycle C [28]. Finally, reductive elimination delivers Quinapo 3a while concomitantly releasing the catalyst Pd(0) for the next catalytic cycle.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 3. Proposed mechanism. | |

With these racemic Quinapos in hand, we arbitrarily selected 3a as the potential ligand. The resolution of 3a was achieved by transformation to the diastereomeric esters with (S)-BINOL or mono-methylated (S)-MeBINOL, which were easily separated at this stage via column chromatography on silica gel (Scheme 4), affording the Quinapo derivatives 5, 6, 9 and 10. Subsequently, Quinap esters 7, 8, 11 and 12 were obtained in moderate to high yields from Quinapo derivatives 5, 6, 9, and 10 by the reduction with HSiCl3. The absolute configurations of ligands 7 and 12 were shown to be (S) and (R) by X-ray single-crystal analysis (CCDC: 2367490 and CCDC: 2367487), respectively.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 4. Synthesis of ligands 7, 8, 11 and 12. | |

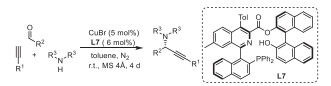

Then, we tried the enantioselective A3-coupling for the synthesis of chiral propynyl amines (Table 2). First, ligands 7, 8, 11 and 12 were screened by the reaction of cyclohexanecarbaldehyde, dibenzylamine and ethynyltrimethylsilane, ligand 7 give the better results, regarding the yield and ee value (Table 2, entries 1 vs. 2–4). It should be mentioned the ee value by ligand 7 is higher than that by Quinap (Table 2, entry 1) [44]. Therefore, the most challenging linear aliphatic (Table 2, entries 6 and 7) and aromatic aldehydes (Table 2, entries 8–22) in A3 reaction were screened by using ligand 7. As shown in Table 2, the reactions were generally highly enantioselective over a range of aldehydes. Remarkably, electron-rich or -poor aromatic aldehydes, naphthaldehyde, heteroaryl aldehydes and ferrocenecarboxaldehyde have little effect on enantioselectivity, whereby the ee values much higher than those obtained by Quinap (entries 8–13, 15–18, 21 and 22) [45,46]. Furthermore, 2-methyl and 2-bromobenzaldehydes gave 95% and 80% ee (Table 2, entries 19 and 20), whereas Quinap affording 32% and 25% ee, respectively [46]. In the enantioselective A3-coupling, Quinap demonstrated a strong positive nonlinear effect [45], while a perfect linear effect was displayed between the enantiopurity of ligand L7 and product (Fig. 1). This result indicated that a monomeric copper(Ⅰ) complex with a single chiral ligand is most likely involved as the catalytically active species, which signal with m/z of 918.20 by ESI mass spectrometric experiment matched the m/z of mono-ligated species [Cu(L7)]+ (Fig. 1, calcd. for C60H42CuNO3P+: 918.2). It is very possible that the bulky BINOL ester group on 3-position of L7 causes the distinct coordination mode of copper with ligand L7 or Quinap and renders the chiral amine products in higher enantioselectivity. A plausible mechanism of this A3 coupling was proposed in Fig. S3 (Supporting information).

|

|

Table 2 Enantioselective A3-coupling employing ligands 7, 8, 11 and 12.a |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. The linear effect and ESI-MS study. | |

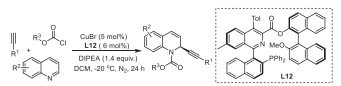

Subsequently, an enantioselective copper-catalyzed addition of alkynes to quinolinium salts was tested (Table 3) [47–49]. After optimization of the reaction conditions (see Supporting information for details), we found that the desired adduct was obtained in 71% yield with 92% ee, when treating quinoline with chloroformate and phenyl acetylene in the presence of CuBr (5 mol%) and P, N-ligand 12 (6 mol%) (Table 3, entry 1). The enantioselectivity reported previously was 42% ee when Quinap was employed as ligand [46]. This three-component reaction delivered the dearomative alkynylation products in high yields with high ee values (Table 3, entries 2–11). This enantioselective alkynylation tolerates a range of functional groups with respect to the three kinds of starting materials, and no significant electronic effect on the stereoselectivity was observed.

|

|

Table 3 Enantioselective copper-catalyzed quinoline alkynylation using L12.a |

In summary, we have developed an efficient and straightforward strategy for the expeditious synthesis of a wide range of isoquinoline ring-modified Quinapos through a palladium-catalyzed imidoylative cyclization of arylethenyl isocyanides and 2-diphenylphosphinyl-1-naphthyl bromides. This reaction tolerates many functional groups, is easy scale-up and renders Quinap derivatives with substitution patterns not obtained using coupling reactions. A new class of chiral biaryl P, N-ligand combining Quinap and BINOL is readily available and has been illustrated to be superb chiral ligands for the copper-catalyzed enantioselective A3-coupling reaction as well as asymmetric quinoline alkynylation. Compared to the wee-known unsubstituted Quinap ligand, the remarkable features of this work are: (a) The readily accessible a wide range of isoquinoine ring-modified Quinapos could permit fine tuning of the steric and electronic effects, which is possible to make Quinap derivatives good performance in a broad scope of catalytic asymmetric reactions; (b) The combination with CuBr forms an efficient catalytic system that has been applied to various challenging substrates with more higher enantioselectivity than those using Quinap; (c) It is most likely that monomeric copper(Ⅰ) complex with a single chiral ligand L7 was formed and served as the catalytically active species. Further studies aimed at their application are underway in our laboratories.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statementGuodong Wang: Investigation. Mengying Jia: Writing – original draft, Project administration. Haitao Liu: Investigation. Yong Liu: Investigation. Zhiguo Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Xianxiu Xu: Supervision, Conceptualization.

AcknowledgmentsFinancial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22171168), Excellent Youth Foundation of Henan Scientific Committee (No. 222300420012) and Taishan Scholar Program of Shandong Province is gratefully acknowledged.

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2024.110705.

| [1] |

N.W. Alcock, J.M. Brown, D.I. Htimes, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 4 (1993) 743-756. |

| [2] |

E. Fernández, P.J. Guiry, P.T. Kieran, et al., J. Org. Chem. 79 (2014) 5391-5400. DOI:10.1021/jo500512s |

| [3] |

B.V. Rokade, P.J. Guiry, ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 624-643. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.7b03759 |

| [4] |

R.W. Baker, S.O. Rea, M.V. Sargent, et al., Tetrahedron 61 (2005) 3733-3743. |

| [5] |

T. Thaler, F. Geittner, P. Knochel, Synlett 17 (2007) 2655-2658. |

| [6] |

J. Clayden, S.P. Fletcher, J.J.W. McDouall, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 (2009) 5331-5343. DOI:10.1021/ja900722q |

| [7] |

V. Bhat, S. Wang, B.M. Stoltz, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 16829-16832. DOI:10.1021/ja409383f |

| [8] |

P. Ramírez-López, A. Ros, B. Estepa, et al., ACS Catal. 6 (2016) 3955-3964. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.6b00784 |

| [9] |

P.Y. Jiang, S. Wu, G.J. Wang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202309272. |

| [10] |

M. McCarthy, R. Goddard, P.J. Guiry, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 10 (1999) 2797-2807. |

| [11] |

D.J. Connolly, P.M. Lacey, M. McCarthy, et al., J. Org. Chem. 69 (2004) 6572-6589. |

| [12] |

T.F. Knöpfel, P. Aschwanden, T. Ichikawa, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43 (2004) 5971-5973. DOI:10.1002/anie.200461286 |

| [13] |

P. Zarotti, T.F. Knöpfel, P. Aschwanden, ACS Catal. 2 (2012) 1232-1234. DOI:10.1021/cs300146x |

| [14] |

F.S.P. Cardoso, K.A. Abboud, A. Aponick, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 14548-14551. DOI:10.1021/ja407689a |

| [15] |

S. Yin, K.N. Weeks, A. Aponick, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146 (2024) 7185-7190. DOI:10.1021/jacs.4c00873 |

| [16] |

B.V. Rokade, P.J. Guiry, ACS Catal. 7 (2017) 2334-2338. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.6b03427 |

| [17] |

P.H.S. Paioti, K.A. Abboud, A. Aponick, ACS Catal. 7 (2017) 2133-2138. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.7b00133 |

| [18] |

Q. Liu, H.B. Xu, Y.L. Li, et al., Nat. Commun. 12 (2021) 19. |

| [19] |

H. Doucet, J.M. Brown, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 8 (1997) 3775-3784. |

| [20] |

V. Nenajdenko, Isocyanide Chemistry Applications in Synthesis and Materials Science, Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2012.

|

| [21] |

V.P. Boyarskiy, N.A. Bokach, K.V. Luzyanin, et al., Chem. Rev. 115 (2015) 2698-2779. DOI:10.1021/cr500380d |

| [22] |

J. Zhang, P. Yu, S.Y. Li, et al., Science 361 (2018) 1087-1095. |

| [23] |

J. Zhang, S.-X. Lin, D.-J. Cheng, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137 (2015) 14039-14042. DOI:10.1021/jacs.5b09117 |

| [24] |

J.W. Collet, T.R. Roose, B. Weijers, et al., Molecules 25 (2020) 4906-4957. DOI:10.3390/molecules25214906 |

| [25] |

T. Nanjo, C. Tsukano, Y. Takemoto, Org. Lett. 14 (2012) 4270-4273. DOI:10.1021/ol302035j |

| [26] |

Z.Y. Gu, T.H. Zhu, J.J. Cao, et al., ACS Catal. 4 (2014) 49-52. DOI:10.1021/cs400904t |

| [27] |

S. Tang, S.W. Yang, H. Sun, et al., Org. Lett. 20 (2018) 1832-1836. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00346 |

| [28] |

J. Li, Y. He, S. Luo, et al., J. Org. Chem. 80 (2015) 2223-2230. DOI:10.1021/jo502731n |

| [29] |

S. Tang, J. Wang, Z. Xiong, et al., Org. Lett. 19 (2017) 5577-5580. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02725 |

| [30] |

W.M. Hu, F. Teng, H. Hu, et al., J. Org. Chem. 84 (2019) 6524-6535. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.9b00683 |

| [31] |

S.B. Nallapati, B. Prasad, B.Y. Sreenivas, et al., Adv. Synth. Catal. 358 (2016) 3387-3393. DOI:10.1002/adsc.201600599 |

| [32] |

T. Tang, X. Jiang, J.M. Wang, et al., Tetrahedron 70 (2014) 2999-3004. |

| [33] |

J. Wang, D.W. Gao, J. Huang, et al., ACS Catal. 7 (2017) 3832-3836. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.7b00731 |

| [34] |

S. Luo, Z. Xiong, Y. Lu, et al., Org. Lett. 20 (2018) 1837-1840. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00348 |

| [35] |

F. Teng, T. Yu, Y. Peng, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 2722-2728. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c00640 |

| [36] |

T. Yu, Z.Q. Li, J. Li, et al., ACS Catal. 12 (2022) 13034-13041. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.2c04461 |

| [37] |

J. Wang, Z. Li, S. Bai, Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107823. |

| [38] |

X. Guo, J. Dong, Y. Zhu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107608. |

| [39] |

Z.Y. Hu, J.H. Dong, Y. Men, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 1805-1809. DOI:10.1002/anie.201611024 |

| [40] |

Z. Hu, H. Yuan, Y. Men, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55 (2016) 7077-7080. DOI:10.1002/anie.201600257 |

| [41] |

X. Xu, L. Zhang, X. Liu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52 (2013) 9271-9274. |

| [42] |

J. Tan, X. Xu, L. Zhang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48 (2009) 2868-2872. DOI:10.1002/anie.200805703 |

| [43] |

Y. Li, X. Xu, J. Tan, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133 (2011) 1775-1777. DOI:10.1021/ja110864t |

| [44] |

Y.N. Ma, S.X. Li, S.D. Yang, Acc. Chem. Res. 50 (2017) 1480-1492. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00167 |

| [45] |

N. Gommermann, C. Koradin, K. Polborn, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42 (2003) 5763-5766. |

| [46] |

N. Gommermann, P. Knochel, Chem. Eur. J. 12 (2006) 4380-4392. DOI:10.1002/chem.200501233 |

| [47] |

D.A. Black, R.E. Beveridge, B.A. Arndtsen, J. Org. Chem. 73 (2008) 1906-1910. DOI:10.1021/jo702293h |

| [48] |

M. Pappoppula, F.S.P. Cardoso, B.O. Garrett, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 5202-15206. |

| [49] |

Z. Gao, J. Qian, H. Yang, et al., Org. Lett. 23 (2021) 1731-1737. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c00156 |

2025, Vol. 36

2025, Vol. 36