b School of Engineering, Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou 311121, China

In an era of rapid medical and technological advancement, cancer continues to present a significant challenge, characterized by its aggressive nature and persistently poor prognosis [1,2]. The pursuit of precision in cancer diagnostics is of paramount importance, as it facilitates early detection and intervention, which are essential for improving patient survival rates [3,4]. However, traditional diagnostic methodologies are encumbered by their lack of specificity, high costs, and an overreliance on tumor growth metrics. Furthermore, state-of-the-art molecular diagnostics are beset by low sensitivity, extended detection timeframes, and potential safety risks, collectively limiting their efficacy in the critical window of early diagnosis [5,6].

Phototheranostics has emerged as a transformative approach to cancer diagnosis and therapy, distinguished by its non-invasive nature and precision in cancer therapy [7,8]. Upon light activation, phototheranostic agents are capable of emitting fluorescence or photoacoustic signals, which enable real-time diagnostic imaging. Additionally, they can also generate heat through photothermal therapy (PTT) or induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) via photodynamic therapy (PDT), thereby facilitating targeted in-situ treatment and thereby enhancing the synergistic effects of diagnostic and therapeutic endeavors [9-11]. The judicious selection of phototheranostic agents, therefore, stands as a critical linchpin for achieving optimal outcomes in the phototheranostics domain.

Organic photovoltaic materials, especially the organic small molecules integral to organic solar cells (OSCs), have garnered significant attention for their exceptional light-harvesting capabilities and wide absorption spectra across the near-infrared (NIR) region, thereby improving the conversion efficiency of solar energy to electrical power [12,13]. Among various types of OPV materials, non-fullerene electron acceptors (NFAs), comprising a fused-ring molecular backbone, have undergone significant enhancement in their light-harvesting capabilities, bandgap narrowing, and NIR absorption properties substantially improved through the ongoing optimization of their core, end units, and side chains. These advancements have not only broadened their applicability across PTT, PDT, and FLI but also highlighted their significant advantages in the development of high-performance phototheranostic agents with considerable potential [14-16].

Emerging as the dark horse in the phototheranostic field, both A-D-A-type and A-D-A'-D-A-type NFAs have demonstrated their unique capabilities in the development of high-performance phototheranostic agents. Despite the emergence of numerous systematic review studies in the field of phototheranostics, a comprehensive review in this field based on NFAs is still relatively lacking. Given the remarkable potential of NFAs in phototheranostics, this review aims to fill this gap by analyzing and summarizing the progress and molecular design strategies of NFAs in phototheranostics, providing a reference and inspiration for future research directions. This review commences with an in-depth exploration of the applications of organic photovoltaic small molecules, particularly focusing on NFAs, within the phototheranostic landscape (Table 1) [17-54]. Subsequently, we provide a comprehensive synthesis of molecular strategies for the design of high-performance phototheranostic agents based on NFAs, encompassing a multifaceted perspective that includes treatment, imaging, and other critical dimensions. These strategies are meticulously crafted to enhance PTT, PDT, and FLI capabilities, and to elevate the overall performance, thereby offering a strategic roadmap for the innovation and design of high-performance phototheranostic agents suitable for clinical applications. By comprehensively analyzing the application of NFAs in phototheranostics, this review provides effective reference for more researchers dedicated to the development of the intersection of photovoltaics and phototheranostics. As the first systematic review article on the application of NFAs in phototheranostics, its significance lies not only in filling the existing literature gap but also in providing a solid theoretical foundation and practical guidance for future research directions.

|

|

Table 1 CSummary of biomedical NFAs' properties including maximum absorption and emission wavelength of the NPs, and biomedical applications. |

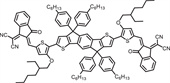

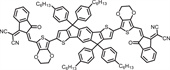

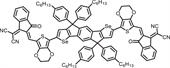

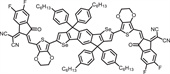

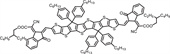

To effectively explore the potential of phototherapy within the intricate environment of living organisms, it is essential to utilize phototheranostic agents with exceptional absorption properties in the NIR spectrum. This attribute is crucial for ensuring significant tissue penetration, which is a fundamental requirement for the success of therapy. This feature is not only essential in amplifying sensitivity and enhancing spatiotemporal resolution but also crucial for extending the absorption spectrum into the second near-infrared region (NIR-Ⅱ, 1000–1700 nm). This spectral range is particularly advantageous due to its diminished scattering and absorption by biological constituents, thereby significantly augmenting the therapeutic reach and efficacy [55-57]. Our prior discussions have thoroughly investigated the methodologies to effectuate a pronounced red-shift in the absorption spectrum, harnessing the intrinsic attributes of the established photosensitizer BODIPY [57]. NFAs, as promising candidates in the realm of phototheranostic materials, offer an unprecedented level of structural adaptability. This flexibility is of great importance for the precise modulation of the absorption spectrum through the strategic manipulation of the electronic push-pull interaction between the donor and acceptor moieties. Such manipulation is designed to enhance intramolecular charge transfer (ICT), as elucidated in Fig. 1. The electron-donating or withdrawing ability of these donor and acceptor groups is crucial for the ICT effect, thus enabling the precise tuning of the absorption spectrum to align with the NIR-Ⅱ window. This fine-tuning is essential for optimizing the agents for deeper tissue penetration and for realizing their full therapeutic potential [58,59]. The common NFAs are classified into two principal structural archetypes: the A-D-A and A-D-A'-D-A configurations. Each of these architectures provides unique opportunities for molecular engineering, offering a myriad of opportunities to tailor the photophysical properties to meet the exacting demands of phototheranostic applications.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Relationship between ICT effects and the selection of donor and acceptor units in NFAs. Reproduced with permission [59]. Copyright 2022, John Wiley and Sons. | |

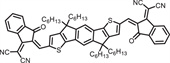

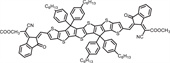

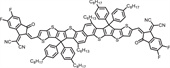

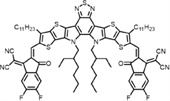

The A-D-A type NFAs are distinguished by their molecular architecture, which comprises two electron-deficient acceptor end groups (A) coupled with a central electron-rich donor unit (D). This configuration endows them with a broad absorption spectrum that spans the visible to near-infrared regions. The precise tuning of the donor and acceptor units, whether in isolation or in conjunction, allows for a subtle modulation of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy levels. This strategic fine-tuning effectively modulates the bandgap, enabling a customized absorption spectrum tailored for phototherapy applications. Moreover, the introduction of elongated alkyl chains not only improves molecular solubility but also enhances planarity, thus promoting the self-assembly into micelles and the subsequent formation of nanoparticles (NPs) through enhanced π-π stacking [60,61].

In a pioneering study published in 2019, Dong et al. [17] charted new territory by exploring the application of the prototypical A-D-A type NFA molecule, ITIC, in biological therapy. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the carbonyl and cyano groups at the molecule's electron-deficient termini serve as formidable electron-withdrawing units, significantly depressing the LUMO energy level. This results in a lowering of the HOMO and LUMO energy levels to −5.48 eV and −3.83 eV, respectively. The incorporation of long alkyl chains not only enhances solubility but also modulates molecular planarity, enabling the spontaneous self-assembly into micelles that culminate in the formation of ITIC NPs. These ITIC NPs, with a small particle size below 40 nm, effectively utilize the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect to reach tumor sites. They also exhibit an excellent photothermal conversion efficiency (PCE) at 660 nm, with a PCE value of 41.6%, which facilitates the thermal ablation of tumors.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) Schematic diagram of ITIC structure and synthesis of nanomaterials for biological applications. (b) Absorption spectra of ITIC and ITIC NPs. (c) DLS and TEM images of ITIC NPs. Reproduced with permission [17]. Copyright 2019, Royal Society of Chemistry. | |

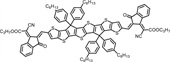

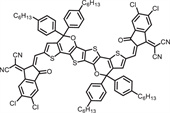

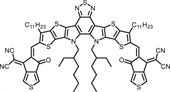

Building upon the remarkable PCE of ITIC, Chen et al. [37] initiated an optimization process of the electron-rich central core, yielding CPDT molecules with an even more constricted bandgap (HOMO and LUMO energy levels at −5.41 eV and −3.50 eV, respectively). As depicted in Fig. 3, the augmented ICT effects endow CPDT with a red-shifted absorption spectrum, extending to 800 nm. FA-CNPs, the nanoparticles derived from CPDT, demonstrate broad absorption up to 950 nm, allowing for profound penetration into tumor tissues. The high PCE (36.5%) and distinguished singlet oxygen quantum yield (Φ = 18.6%) of FA-CNPs enable more effective tumor inhibition through a synergistic PTT/PDT therapeutic approach.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) Schematic diagram of CPDT structure and synthesis of FA-CNPs for biological applications. (b) Absorption spectra. (c) HOMO-LUMO energy level diagram. (d) Survival rate of Hela cells under different conditions. Reproduced with permission [37]. Copyright 2020, John Wiley and Sons. | |

Furthermore, as elucidated in Fig. 4, leveraging the superior electron-donating capacity of the thiophene ring over the benzene ring, the benzene ring in the electron-rich core of ITTC was strategically replaced with a fused-thiophene unit, yielding the ETTC molecule [18,27]. This strategic substitution enhances the D-A interaction, resulting in a pronounced red shift of the maximum absorption peak to 750 nm. The ETTC molecule not only maintains the synergistic PTT/PDT therapeutic efficacy but also unveils superior NIR-Ⅱ fluorescence/photoacoustic imaging capabilities, paving the way for PTT/PDT synergistic therapy guided by advanced NIR-Ⅱ imaging modalities.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (a) Schematic diagram of ITTC structure, synthesis of ITTC NPs for biological applications and the absorption spectra. Reproduced with permission [18]. Copyright 2021, Royal Society of Chemistry. (b) Schematic diagram of ETTC structure, synthesis of ETTC NPs for biological applications and the absorption spectra. Reproduced with permission [27]. Copyright 2021, Royal Society of Chemistry. | |

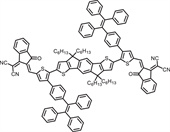

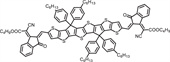

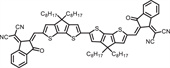

The A-D-A'-D-A class of NFAs is distinguished by its capacity to integrate an extra acceptor unit within the electron-rich core 'D', thereby amplifying the intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) process. This strategic molecular engineering allows for precise modulation of absorption spectra and energy levels, leading to an enhanced absorption profile and a more compact optical bandgap [59,62]. These molecules have not only demonstrated significant potential in the realm of organic photovoltaics but also hold immense promise in the emerging field of phototheranostics.

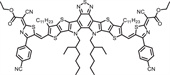

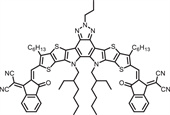

Y6, a representative of the A-D-A'-D-A type NFAs, is renowned for its strong light absorption capabilities. The extended alkyl chains and the rotational freedom at the junction linking the electron donor group to the central nucleus in Y6 are pivotal in augmenting its PTT capabilities. Moreover, the compact singlet-triplet energy gap in Y6 facilitates efficient intersystem crossing (ISC), thereby promoting the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and enhancing its PDT efficacy. In 2021, Han et al. [41] validated the therapeutic potential of Y6 molecules in oncology, demonstrating that Y6 NPs could achieve commendable PTT (PCE = 36.5%) and PDT at 808 nm, accompanied by NIR-Ⅱ fluorescence imaging (FLI) and a fluorescence quantum yield reaching up to 2.8% (Fig. 5a). The pronounced absorption of Y6 in the NIR window provides a distinct advantage in addressing deep-seated tumors. Lan et al. [49] further optimized Y6 by modifying the alkyl chains, yielding BTP-4F-DMO, which retains a small energy gap (Fig. 5b). BTP-4F-DMO NPs exhibit broad absorption at 808 nm and demonstrate superior PTT performance (PCE = 90.5%), along with the capacity to concurrently generate both hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and singlet oxygen (1O2) for type Ⅰ and type Ⅱ PDT, thereby inducing autophagy to accelerate cancer cell death.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. (a) Schematic diagram of Y6 structure, preparation of nanoparticles, absorption and emission spectra and biological applications. Reproduced with permission [41]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (b) Structure of BTP-4F-DMO, preparation of nanoparticles, absorption spectra, expression of characteristic proteins, and schematic diagram of biological applications. Reproduced with permission [49]. Copyright 2023 Elsevier. | |

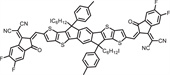

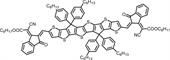

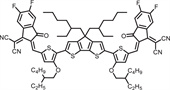

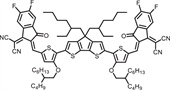

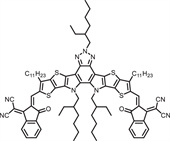

In the A-D-A'-D-A type NFAs, the electron-deficient core A' serves as a distinctive feature of the Y-series molecules. In addition to benzothiazole (BT), which is present in Y6 molecules as A', 2-alkylbenzotriazole (BTz) emerges as another prevalent A' moiety. Alkyl chain modification on the central nitrogen atom acts as a shielding group, preventing excessive π-π stacking and thereby enhancing fluorescence properties [63,64]. As depicted in Fig. 6, Lin et al. [52] developed an BTz-based A-D-A'-D-A type NFA, designated Y16-Pr. The resulting Y16-Pr NPs with broad absorption across the 600–900 nm range, excellent PTT (PCE = 82.4%) and PDT (Φ = 8.3%) performance. Y16-Pr NPs are capable of achieving synergistic therapy combining NIR-Ⅱ FLI-guided type Ⅰ/Ⅱ PDT and PTT, making it a promising candidate for high-performance phototheranostic agents.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. (a) Schematic diagram of Y16-Pr structure, nanoparticle preparation, and biological application. Absorption spectra of (b) Y16-Pr and (c) Y16-Pr-PEG NPs. Reproduced with permission [52]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. | |

Phototheranostic agents are primarily instrumental in therapeutic endeavors through the mechanisms of PTT and PDT. The A-D-A type and A-D-A'-D-A type NFAs have consistently demonstrated robust PTT and PDT capabilities, and in some instances, have been shown to achieve a synergistic therapeutic effect when PTT and PDT are combined [23,35,44,53]. The efficacy of these agents depends on the activation by light of a certain intensity. However, excessive laser power can lead to unintended thermal injuries [65,66]. Thus, optimizing these molecules for efficacious phototherapy at lower laser power thresholds has become a critical focal point in the engineering of high-performance phototheranostic agents.

In this discourse, we provide a detailed account of the methodologies aimed at amplifying the therapeutic index of NFAs within biological matrices, with a particular focus on the optimization of PTT and PDT performance. It is our aspiration that this strategy will provide a valuable reference point for the innovation and modification of phototherapeutic molecules with the potential to set new standards in performance.

3.1. Strategy for enhancing PTT performancePCE is a cardinal parameter for evaluating PTT performance. An insufficient PCE necessitates higher laser intensities to ensure effective thermal ablation of tumors, potentially causing unintended thermal damage to surrounding healthy tissues [67,68]. Thus, the imperative to develop photothermal agents with enhanced PCE is self-evident.

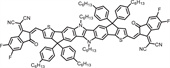

The ability of intramolecular rotation is a key determinant in facilitating non-radiative decay pathways, which are directly associated with improved PCE [69-71]. In a pioneering study in 2019, Lee et al. [29] presented F8-IC, a molecule with an A-D-A configuration, which upon self-assembly with DSPE-PEG2000, yielded F8-PEG nanoparticles. These nanoparticles exhibited a remarkable PCE, reaching up to 82%, and demonstrated outstanding therapeutic efficacy both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 7). Molecular dynamics simulations revealed that the flexible D-A bonds within F8-IC enhance intramolecular rotation capability, which is pivotal to the heat generation mechanism. This finding provides crucial insights into the elevated PCE typically associated with A-D-A type and A-D-A'-D-A type NFAs. Moreover, the near-zero fluorescence quantum yield of these nanoparticles indicates that absorbed light energy is almost entirely converted into heat, thereby further boosting PCE.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 7. (a) The optimized structure model of F8IC and the efficient treatment mechanism of F8-PEG NPs. (b) Preparation of F8-PEG NPs. (c) Heating effect and tumor suppression ability of F8-PEG NPs in mice. Reproduced with permission [29]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. | |

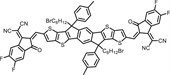

The presence of twisted intramolecular charge transfer (TICT) in the excited state, under conditions that permit a certain degree of intramolecular rotation, is advantageous for the generation of non-radiative decay, thereby augmenting PTT performance [72-74]. In an innovative 2023 study, Li et al. [28] synthesized a series of A-D-A type molecules, CP-F7, CP-F7P, and CP-F8P, with different donor structures created by varying the number of conjugated rings within the donor moiety (Fig. 8). By carefully adjusting the donor structure, they observed that an increment in the number of conjugated rings progressively heightened the electron-donating capacity of the central core in CP-F7, CP-F7P, and CP-F8P. This modulation progressively diminished the energy gap, promoted TICT, and resulted in a significant enhancement of PCE. This pioneering work underscores the viability of modulating the PTT attributes of conjugated molecules by tuning their electron-donating ability, offering a novel approach to the strategic design of efficient, skeleton-tunable photothermal materials.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 8. (a) The structures of CP-F7, CP-F7P and CP-F8P. (b) Preparation of the NPs. (c) Illustration of energy release and biological application. (d) HOMO-LUMO energy level diagram. (e) Comparison of heating capabilities. Reproduced with permission [28]. Copyright 2023, John Wiley and Sons. | |

The therapeutic efficacy of PDT is well-established and based on the lethal reaction of ROS with the protean canvas of intracellular proteins and biomolecules within cancer cells. The generation of ROS is a process that can be significantly enhanced by promoting intersystem crossing (ISC), thereby improving PDT performance [75,76]. The ISC rate constant formula dictates that the stimulation of ISC can be achieved by escalating the spin-orbit coupling constant (SOC) and simutaneously lowering the singlet-triplet energy gap (ΔEST) [77,78]. While the incorporation of heavy atoms is a recognized method for augmenting SOC, the inherent toxicity of such atoms raises a range of biosafety concerns [79-82].

In the intricate dance of photosensitization, molecules in an excited state can return to the ground state through a spectrum of radiative transitions, including fluorescence, delayed fluorescence, and phosphorescence, or through non-radiative pathways, which include vibrational relaxation, internal conversion, and ISC (Fig. 9). Optimizing PDT efficacy requires strategically suppressing these energy-dissipating mechanisms [83]. It is crucial to recognize that photosensitizer molecules do not operate in a vacuum but are embedded in a microenvironment with a multitude of similar molecules. These molecules engage in crosstalk, culminating in the formation of aggregates driven by specific forces and interactions [84,85]. The aggregation process significantly impacts the probabilities of the various transitions occurring, and the electronic structure is subject to pervasive molecular electronic coupling effects that exist between orbitals, excitons, and the kinetics between excited and ground states [86-88]. Such coupling effects can alter transition dipole moments and reconfigure energy levels. The aggregation of molecules, influenced by their stacking pattern and density, are crucial factors in modulating PDT performance, highlighting the importance of understanding molecular aggregation in the design of efficient photosensitizers.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 9. Excited state deactivation processes. | |

Reducing the planarity of π-conjugated molecules to promote less rigid stacking geometries can strengthen interactions with neighboring substrates and facilitate electron transfer processes, thereby enhancing the efficacy of PDT [89-91]. Building on this principle, Liu et al. [21] presented an A-D-A type molecule, TIDT, which shares the donor core with ITIC and incorporates a tricyanofuran-based group onto the IC end. This modification markedly redcues molecular planarity, weakens π-π stacking, and induces unique PDT properties absent in ITIC (Fig. 10). Utilizing a variety of probes to detect ROS, including 2′, 7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCFH) for ROS, singlet oxugen sensor green (SOSG) for 1O2, aminophenyl fluorescein (APF) for •OH, and dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR123) for O2•−, it was confirmed that TIDT-PEG nanoparticles are capable of inducing both type Ⅰ and type Ⅱ PDT concurrently.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 10. (a) The structure of TIDT and its biological applications. (b) Fluorescence spectral changes of TIDT NPs mixed with DCFH, SOSG, APF, DHR123 probes under 660 nm laser irradiation. Reproduced with permission [21]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier. | |

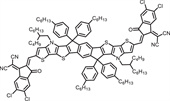

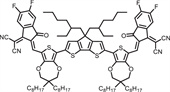

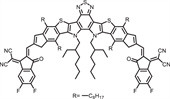

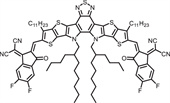

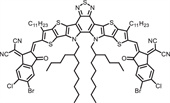

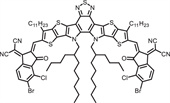

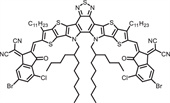

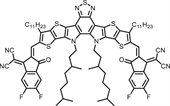

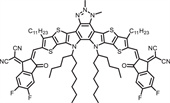

In contrast, other studies have opposing views on the influence of molecular stacking on PDT activity. For example, Tian et al. [51] introduced a strategy to enhance molecular stacking through chlorine-mediated interactions, aiming to amplify intermolecular π-π coupling and improve the PDT efficacy of NIR-Ⅱ emissive photosensitizers with extensive π-conjugated structures (Fig. 11). Experimental evidences reveal that non-covalent halogen interactions can significantly modulate π-π stacking in nanoparticles. The C–Cl bond, characterized by a substantial dipole moment, facilitates the formation of stronger intermolecular forces. X-ray single-crystal structure analysis indicates that BMIC-BO-4Cl, organized by Cl-mediated intermolecular interactions, achieves a more compact molecular stacking arrangement compared to the F-substituted BMIC-BO-4F. This enhanced intermolecular π-π coupling improves light harvesting capacity, charge separation, and conduction capabilities of the aggregates, effectively boosting photodynamic reactions on the nanoparticle surface. Despite exhibiting analogous photophysical properties in their monomeric state, the PDT efficacy of BMIC-BO-4Cl is approximately 1.7-fold greater than that of BMIC-BO-4F nanoparticles in the aggregated nanoparticle state, underscoring its potential as an outstanding NIR-Ⅱ emissive photosensitizer.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 11. (a) Illustration of A-D-A type π-conjugated small molecules, BMIC-BO-4Cl and BMIC-BO-4F. (b) ROS generation and fluorescence intensity change of DHR 123 (for O2•− detection), APF (for •OH detection) and SOSG (for 1O2 detection) in the presence of NPs. (c) Crystal structures and aggregation behaviors, packing modes, side and top views of the extended-crystal structure and energy/charge passages by single-crystal analysis. Reproduced with permission [51]. Copyright 2023, John Wiley and Sons. | |

The divergent findings from these studies are scientifically plausible, as altering molecular packing density involves changes in energy levels, leading to specific structural adaptations and numerous factors that influence PDT activity [83,92]. Consequently, in the pursuit of engineering photosensitizers with enhanced PDT performance, a simplistic approach that pursues either increased compactness or reduced molecular packing density is a reductionist perspective.

3.2.2. Energy level adjustmentPDT is classified into two categories including type Ⅰ and type Ⅱ according to the distinctive pathways of ROS generation (Fig. 12). Type Ⅱ PDT, which generates 1O2 through an energy transfer mechanism, is highly oxygen-dependent. However, the tumor microenvironment often exists in a state of hypoxia, which greatly attenuates the therapeutic efficacy of type Ⅱ PDT at tumor sites [93,94]. Conversely, type Ⅰ PDT, which produces •OH or O2•− via electron transfer, is less dependent on oxygen levels, making it a more effective PDT modality under the hypoxic conditions commonly found in tumors [95]. Despite this, there is an inherent competition between energy transfer and electron transfer processes within photosensitization. Photosensitizers typically exhibit a greater propensity for sensitizing oxygen to generate 1O2 through the energy transfer pathway. The lack of effective strategies to direct photosensitizers towards electron transfer over energy transfer for oxygen sensitization remains a significant challenge in the design and development of photosensitizers with type Ⅰ PDT capabilities.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 12. Mechanistic diagrams of PDT. | |

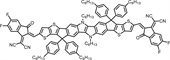

In light of the competition between energy and electron transfer, a sophisticated molecular design approach involves lowering the triplet energy of photosensitizers to suppress energy transfer pathways, thereby selectively enhancing the generation of superoxide anion radicals via the type Ⅰ PDT pathway [96]. As depicted in Fig. 13, Liu et al. [44] introduced an ester-blocked 2-cyanothiazole with robust electron-withdrawing properties to replace the end group of the Y6 molecule, yielding the novel photosensitizer Y6-Th. The detection of 1O2 and •OH was performed using SOSG and HPF as respective probes. Under the irradiation of 808 nm laser, no change in fluorescence intensity was observed. However, with DMPO as the O2•− spin trap reagent, a significant signal peak emerged in the ESR test, indicating the exclusive production of O2•− by Y6-Th. Theoretical analyses of this phenomenon revealed that Y6-Th has a narrow S1-T2 energy gap (0.21 eV), which is instrumental in promoting the ISC process. The S1-T1 energy gap is measured at 0.35 eV, suggesting that the excited state molecules will preferentially decay to the T1 state and then ascend to the T2 state through an internal conversion process. Moreover, from an energetic perspective, the vertical T1-S0 emission energy of Y6-Th is calculated to be 1.03 eV, which is slightly below the threshold required to excite 3O2 to its singlet excited state, thus inhibiting the generation of 1O2. Consequently, the pathway for type Ⅱ PDT in Y6-Th is effectively blocked, resulting in the exclusive manifestation of type Ⅰ PDT.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 13. (a) The structure of Y6-Th and mechanism diagram. (b) Distribution of HOMO-LUMO on the energy level diagram and the energy levels and ΔET1-S0 values. (c) Fluorescence intensity changes and EPR spectrum of the mixed solution of Y6-Th NPs and corresponding probes under 808 nm laser irradiation. Reproduced with permission [44]. Copyright 2024, John Wiley and Sons. | |

Although a variety of photosensitizers have been developed to achieve type Ⅰ PDT, a universal design paradigm for such photosensitizers remains elusive. In 2023, Yang et al. [97] presented an innovative strategy for engineering type Ⅰ photosensitization systems by integrating robust electron acceptors into conventional type Ⅱ photosensitization frameworks through the agency of supramolecular self-assembly, thus enhancing the efficacy of type Ⅰ PDT, as depicted in Fig. 14a. This groundbreaking approach was further developed by Huang et al. [98], who introduced a receptor-mediated light-induced transfer mechanism designed to augment type Ⅰ photosensitization by promoting the dissociation of electron-hole pairs (Fig. 14b). The A-D-A'-D-A type NFA molecule L8-BO-EH-4F (4F) was selected as the electron acceptor, as it is capable of concomitantly generating •OH, O2•−, and 1O2 with the complemention of perylene diimide (PDI) as the electron donor. A range of NPs was synthesized by blending these components in diverse molar ratios. It was observed that these NPs were capable of generating radical ion pairs upon exposure to light, with a variable degree of enhancement in the generation of •OH and O2•−. Notably, the NPs fabricated with an equimolar ratio of 4F to PDI, termed 4F-PDI1, exhibited the most pronounced enhancement effect on ROS, increasing the yield of •OH and O2•− by 3.5-fold and 2.5-fold, respectively, without compromising the inherent 1O2 generation capability. Delving into the underlying mechanism, it was revealed that PDI within the 4F-PDI1 NPs acted as an electron catalyst, significantly amplifying the type Ⅰ photosensitization process. This collection of studies highlights the potential of incorporating electron donors or acceptors through molecular assembly to enhance the electron transfer efficiency of photosensitizers, facilitating a transition from type Ⅱ PDT to type Ⅰ PDT. Moreover, it provides pioneering insights for the conception of novel phototherapeutic agents, specifically tailored for deployment within the hypoxic tumor microenvironment.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 14. (a) The design concept of the type Ⅰ photosensitive system in the previous work. (b) Schematic diagram of enhancing the type Ⅰ sensitization process by promoting electron-hole pair separation. (c) ROS, •OH, O2•−, and 1O2 generation capabilities of different component NPs under the same conditions. Reproduced with permission [98]. Copyright 2024, John Wiley and Sons. | |

Optical imaging represents a fundamental component of the diagnostic toolkit, with key contributions from both photoacoustic imaging (PAI) and fluorescence imaging (FLI). PAI emerges as a byproduct of PTT processes, and its enhancement strategies are fundamentally aligned with those delineated for PTT in Section 3.1, thus requiring no further explication at this juncture. The domain of NIR FLI, and notably the NIR-Ⅱ FLI, has distinguished itself as an exceptional imaging modality. It is distinguished by superior tissue penetration, minimal interference from autofluorescence, an elevated signal-to-noise ratio, and diminished potential for photodamage, underscoring its indispensable role in the phototheranostics continuum [99-101].

The optimization of FLI performance is often pursued by strategies that encourage a red-shifted absorption profile suitable for NIR-Ⅱ FLI or by amplifying the fluorescence quantum yield [26]. Key approaches to achieve a redshift in absorption include the expansion of π-conjugated systems, the enhancement of donor-acceptor (D-A) interactions, and the assembly into J-aggregates. Given that certain facets of these approaches have been previously addressed in Section 2, this section will now focus on an in-depth analysis of the methods available to augment the fluorescence quantum yield.

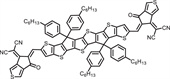

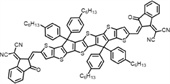

4.1. π-Bridge modificationEnhancing the fluorescence quantum yield is achievable through the strategic modification of the π-bridge to mitigate the impact of excited state TICT or intermolecular π-π interactions. Tang et al. [26] developed a sophisticated molecular engineering approach involving the incorporation of tetraphenylethene into the π-bridge of A-D-A type molecules. This innovative step introduced increased molecular distortion and steric hindrance, effectively reducing molecular stacking and orchestrating a transition from the aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ) to the aggregation-induced emission (AIE) characteristics (Fig. 15). The resulting IDT-TPE NPs displayed a significantly elevated molar absorption coefficient, with the fluorescence quantum yield impressively increased from 0.3% to 1.7%. This research underscores the transformative potential of precise molecular engineering of the π-bridge, which can convert A-D-A type molecules with ACQ tendencies into AIE-active entities, thereby presenting a viable and potent avenue for the innovating fluorescent theranostic agents with enhanced performance.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 15. (a) Schematic diagram of IDT-TPE molecular engineering. (b) Distribution of HOMO-LUMO on the energy level diagram and optimized geometric configuration. (c) Absorption, fluorescence emission, and the corresponding fluorescence quantum yields (inset) of NPs. Reproduced with permission [26]. Copyright 2021, John Wiley and Sons. | |

The side chains integrated into the π-bridge also play a pivotal role in modulating intermolecular π-π interactions. Liang et al. [38] proposed a molecular engineering strategy based on A-D-A type fusion receptor molecules, in which the π-bridge of the original donor was replaced with the sterically bulky 2-octyl-3,4-propylenedioxythiophene (PDOT-C8). This ingenious modification amplified steric hindrance, attenuated intermolecular aggregation, and bolstered the integrity of the conjugated backbone. Subsequently, interactions with water molecules were minimized, resulting in a notable enhancement of fluorescence luminosity, as elegantly portrayed in Fig. 16. The optimized CPTIC-4F nanofluorophores (NFs) showcased an expanded emission profile, extending to 1100 nm, coupled with a fluorescence quantum yield of 0.39% in aqueous media, substantially eclipsing the performance of 3-EHOT-based COTIC-4F NFs. Moreover, the fluorescence brightness of CPTIC-4F NFs outperformed that of COTIC-4F NFs by a remarkable margin of over 20-fold. Equipped with high brightness and extended-wavelength emission, these NFs delivered exceptional imaging capabilities for non-invasive in vivo biological imaging, facilitating the comprehensive visualization of the entire body and cerebral vasculature. The π-bridge engineering exemplified in this work provides profound insights and paves the way for the evolution of molecular designs tailored for high-brightness biological imaging within the NIR-Ⅱ region.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 16. (a) The structure of COTIC-4F, CBTIC-4F, CPTIC-4F, fluorescence promotion effect and bioimaging. (b) Absorption, (c) fluorescence emission and (d) brightness of the three NFs. Reproduced with permission [38]. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature. | |

Imaging in the NIR-Ⅱb window (1500–1700 nm) offers exceptional contrast and the superior capability to penetrate deep tissue layers, thereby enabling the high-definition visualization of microstructures throughout the body [102,103]. Building upon the foundation laid by preceding research, Li et al. [24] selected A-D-A type molecules with a π-bridge structure in 2022 that were suitable for this purpose. By employing cutting-edge atomic programming techniques, they developed an array of semiconductor oligomers with a remarkable capacity for coherent emission in the NIR-Ⅱb spectrum. This was achieved through the innovative introduction of selenium or fluorine substitution (Fig. 17). Notably, the IDSe-IC2F nanoparticles, containing simultaneous selenium and fluorine substitutions, showcased a reduced HOMO-LUMO energy gap. This strategic molecular fine-tuning led to a pronounced red-shift in both absorption and emission, resulting in the emission of bright NIR-Ⅱb fluorescence that extended beyond the 1500 nm boundary. This breakthrough facilitated the high-resolution, in vivo imaging of intricate microstructures, such as the blood vessels of the hind limbs, bile ducts, and bladder in live mice, at depths exceeding the 1500 nm threshold. This study demonstrates a pragmatic and effective approach to the design of organic small molecules, specifically tailored for penetrating deep into tissues for imaging within the NIR-Ⅱb window.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 17. (a) Structures and the energy levels of the HOMOs and LUMOs of IDS-IC, IDSe-IC, and IDSe-IC2F. (b) The preparation of SOM NPs and absorption of IDSe-IC2F NPs. (c) Whole-body imaging and (d) hind limb imaging, as well as (e) biliary and (f) bladder imaging of IDSe-IC2F NPs in NIR-Ⅱ, NIR-Ⅱa, and NIR-Ⅱb windows. Reproduced with permission [24]. Copyright 2022, John Wiley and Sons. | |

The efficacy of a individual therapeutic intervention or imaging modality is inherently constrained by its intrinsic limitations, significantly restricting their practical utility. However, the evolution of multifunctional phototherapeutic agents, based on the precision of single-molecule constructs, has effectively surmounted such constraints. These agents facilitate the accurate identification, diagnosis, and targeted therapy of tumors, propelling the field of precision medicine forward. They enhance the efficacy of treatments and expand the range of potential applications [104]. In light of these advancements, we present a comprehensive strategy for enhancing the multifaceted performance of these agents, particularly those predicated on NFAs. Our objective is to delineate a strategic course that illuminates the path for the innovation of phototherapeutic agents that are not only more robust but also more adaptable and efficient.

5.1. Molecular engineering strategyThe field of molecular engineering, through strategic and precise modification, has unlocked the potential to synthesize molecules that embody both diagnostic and therapeutic functionalities, a concept widely recognized as theranostics. This paradigm has emerged as a highly effective and prevalent strategy for crafting superior performance phototherapeutic agents [57]. The integration of diagnostic capabilities with therapeutic interventions lies in the delicate regulation of the diverse energy dissipation pathways accessible to organic molecules in their excited states. This pathways include radiative decay pathways critical for FLI, ISC mechanisms essential for PDT, and non-radiative decay processes utilized in PAI, photothermal imaging and PTT [105]. Achieving equilibrium within these pathways is a sophisticated endeavor, influenced by various factors including electrostatic interactions, π-π stacking, and steric effects [68,106]. The task of modulating these energy dissipation pathways, despite its inherent complexity when dealing with excited organic molecules, is made more tractable through the versatility of NFAs. Their molecular architecture is characterized by an abundance of modification sites, including spanning side chains, end groups, and π-bridges, which facilitate targeted tailoring. Furthermore, a variety of molecular engineering strategies based on NFAs have been proposed in the literature to effectively regulate these energy dissipation pathways.

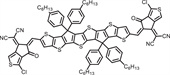

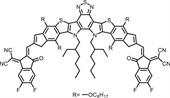

5.1.1. Side-chain modulation strategyThe strategic modification of side chains represents a sophisticated approach to fine-tune the intricate ballet of intermolecular π-π interactions, which in turn influences the molecular stacking and comprehensively modulates aggregate properties. In a pioneering study, Tian et al. [45] introduced a pair of molecules, BDTR9-OC8 and BDTR9-C8, characterized by the presence of a flexible n-octoxy chain and a rigid n-octyl chain at the benzothiadiazole moiety, respectively (Fig. 18). In BDTR9-C8, the rigid side chain induces significant steric hindrance, resulting in an increased angle between the side chain and the π-conjugated plane, forming a geometric alteration notably larger than that induced by the methoxy side chain in BDTR9-OC8. This enhanced steric effect in BDTR9-C8 correlates with stronger intermolecular interaction energies, implying a higher polymerization energy barrier, which in turn leads to a more disordered molecular arrangement within the aggregated state, favoring BDTR9-C8 over BDTR9-OC8. Such an amorphous conformation is instrumental in the more efficacious transmission of excitons and phonons, thereby conferring a marked enhancement in both FLI and PAI. This pioneering work demonstrates that side chain modification is a potent avenue for harmonizing the competitive interplay of energy dissipation pathways.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 18. (a) Diagram of side chain regulation strategy. (b) The optimized geometries of BDTR9-OC8 and BDTR9-C8 and the 2D GIWAXS patterns of the films. (c) In vivo NIR-Ⅱ FLI and PAI of tumor at different time intervals and the signal to background ratio (SBR) for 24 h. (d) Imaging illustration related to (c). Reproduced with permission [45]. Copyright 2022, John Wiley and Sons. | |

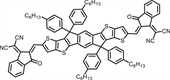

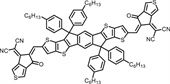

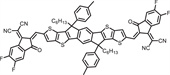

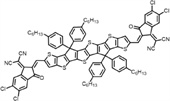

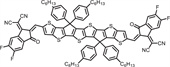

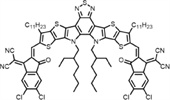

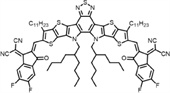

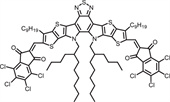

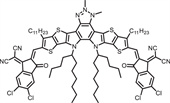

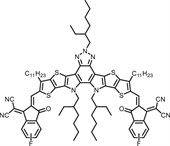

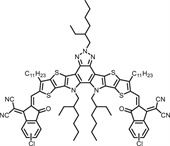

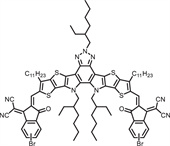

Beyond the realm of side-chain engineering, the targeted alteration of end-groups stands as a cornerstone technique in the photovoltaic modification of NFAs. Inspired by such strategies, Tang et al. [19] focused on the phototheranostic characteristics of a series of NFAs subjected to fluorine and chlorine substitutions (Fig. 19). Their insightful findings revealed that fluorine substitution can significantly increase the electrostatic potential owing to the high electronegativity of fluorine. This enhancement enhances the D-A interactions both within and among molecules, as well as the intermolecular electrostatic interactions in the aggregated state. These combined effects lead to a higher molar extinction coefficient, intensified NIR-Ⅱ fluorescence, and notable improvements in PTT efficacy. This research underscores the potency of fluorination as a strategic approach for the development of highly efficient NIR-Ⅱ phototherapeutic agents.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 19. (a) Fluorination strategy. (b) ESP distributions and surface area distribution with different ESP. (c) Quantum yields and PCE of six NPs. Reproduced with permission [19]. Copyright 2022, John Wiley and Sons. | |

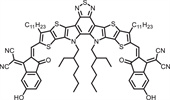

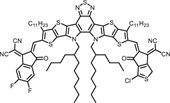

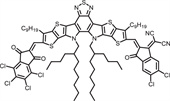

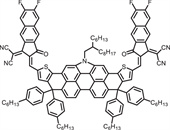

Extending the concept of halogen substitution, the replacement of halogens with alternative functional groups represents a promising avenue for innovation. Yin et al. [50] pioneered this approach by substituting the end groups of the classic photovoltaic molecule BTP-eC9 (BTP-4CN) with 4,5,6,7-tetrachloro-1H-indene-1,3(2H)-dione (TCID), thereby obtaining a series of molecules with different substituents. They systematically investigated the impact of this group replacement on the phototheranostic performance (Fig. 20) and found that the asymmetric molecule BTP-TCID-2CN obtained through appropriate substitution maximized the difference electrostatic potential (∆ESP), ultimately achieving a balance between high FLQY and photothermal conversion performance. Additionally, the biocompatibility and cellular internalization capacity of BTP-TCID-2CN NPs were significantly improved after appropriate introduction of the cyanide group. These characteristics enable BTP-TCID-2CN NPs to safely achieve high-resolution NIR-Ⅱ FLI/PAI-guided PTT in vivo. This work demonstrates the effectiveness of the asymmetric end group strategy of photosensitizers in regulating phototheranostic performance.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 20. (a) Schematic diagram of nitrile-induced molecules enabling balance between NIR-Ⅱ FLI and PTT/PAI. (b) ESP distributions. (c) Temperature elevation, PA intensities and NIR-Ⅱ fluorescence images of different NPs. (d) Live/dead assay, dark-toxicity and phototoxicity of different NPs. Reproduced with permission [50]. Copyright 2023, Royal Society of Chemistry. | |

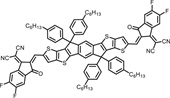

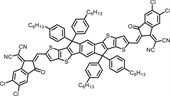

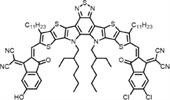

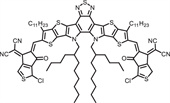

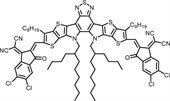

Tian et al. [39] proposed a π-π electronic coupling strategy from different perspectives, augmented by the incorporation of various end groups (Fig. 21). Through meticulous single crystal analysis, it was demonstrated that both BTIC-4Cl and BTIC–OH-δ exhibited relatively planar molecular conformations. However, the chlorine substituent with pronounced steric hindrance induced a more substantial dihedral angle between the ring-fused magnetic core plane of BTIC-4Cl and the IC end group, surpassing that of BTIC–OH-δ. This observation suggests that BTIC–OH-δ with better planar conformation is more conducive to the formation of H-aggregates. Moreover, the presence of hydrogen bonding in BTIC–OH-δ modulates the pattern of π–π stacking, resulting in the formation of smaller frameworks and a more robust π-π electronic coupling. This facilitates the transfer of energy and charge, thereby enhancing PDT performance. However, while π-π stacking is advantageous for PDT, it may not be as beneficial for FLI performance. Therefore, the molecule BTIC-δOH-2Cl, crafted by controlling the introduction of the hydroxyl end group, presents an optimal equilibrium of π-π interactions, harmonizing NIR-Ⅱ FLI and PDT performance. This work illuminates a novel perspective for the future design of NIR-Ⅱ phototheranostic agents.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 21. (a) Hydroxyl end-group regulation strategy. (b) The single-crystal structures and molecular packing of BTIC-4Cl (blue) and BTIC–OH-δ (red) by single-crystal data analysis. (c) Plots of decomposition rates of DPBF (for general ROS detection) and relative PL intensity of SOSG (for 1O2 detection), APF (for •OH detection), and DHR 123 (for O2•− detection). (d) NIR-Ⅱ fluorescence images of three NPs dispersed in water under 808 nm laser irradiation. Reproduced with permission [39]. Copyright 2023, John Wiley and Sons. | |

Although traditional end-group regulation strategies have proven effective in enhancing phototherapy performance, they have been somewhat limited by the static nature of the primary electron-withdrawing group in the end-group, namely the acrylonitrile group. This limitation has restricted the diversity of improvement methods and impeded the evolution of more high-performance phototheranostic agents. In 2023, a pioneering study reported by Lu et al. [32] introduced a series of A-D-A type photosensitizers (F8CA1-F8CA4) featuring end groups modified with cyanobase and adorned with ester side chains of varying lengths (Fig. 22). It was observed that an increase in the steric hindrance of the ester side chains could amplify the photothermal conversion capability. However, this enhancement also had a detrimental influence on fluorescence emission and PDT. The F8CA2 nanoparticles, developed on the basis of this concept, exhibited an optimal balance of steric hindrance and molecular planarity. They not only demonstrated exceptional performance in FLI-guided synergistic PTT and type Ⅰ/Ⅱ PDT but also achieved lysosome targeting. This study introduces a non-planarization strategy for end groups, offering a novel and pragmatic design approach for the creation of multifunctional photosensitizers with organelle-targeting capabilities.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 22. (a) The structure of F8CA1-F8CA4, nanoparticle preparation, and biological application. (b) Lysosome co-localization experiment. Reproduced with permission [32]. Copyright 2023, John Wiley and Sons. | |

The art of oligomerization effectively narrows the bandgap and intensifies the capability for light absorption through π-conjugation extension, while embodying the advantageous characteristics of small molecules and polymers. This approach is distinguished by its precision in crafting well-defined molecular architectures, exacting molecular weights, and commendable reproducibility across different batches [107,108]. Building upon these merits, Tian et al. [109] introduced an innovative dimerization π-conjugation extension strategy (Fig. 23). The high-performing BTIC molecule was selected as the foundational monomer, and its potential was enhanced by the creation of dBTIC-S and dBTIC-D through single and ethylene linkages, respectively. The resulting dimers demonstrated superior performance in both FLI and PTT efficacy compared to the monomer. In particular, the NIR-Ⅱ fluorescence quantum yield of dBTIC-D exhibited an outstanding 8-fold enhancement ralative to the BTIC monomer, and it displayed an impressive ability to effectively ablate tumors at a significantly reduced laser power intensity of 0.3 W/cm².

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 23. (a) Schematic diagram of π-conjugated extension strategy for dimerization. (b) Synthetic routes of dBTIC-S and dBTIC-D. (c) Comparison of fluorescence and photothermal properties between monomer and dimer. Reproduced with permission [109]. Copyright 2024, John Wiley and Sons. | |

Immunotherapy holds the promise of selectively targeting tumor cells while amplifying the host's immune defenses, offering a strategic advantage when combined with modalities such as PTT or PDT. This multi-mode therapeutic approach surpasses the efficacy of any single intervention [110-113], addressing not only localized tumors but also curtailing systemic metastasis, preventing recurrence, and engendering long-lasting immune memory [114,115]. Leveraging these insights, Han et al. [43] identified Y8, a molecule with remarkable PTT and PDT properties, and employed syngeneic mouse splenocytes to evaluate the ensuing antitumor immune response (Fig. 24). The study revealed that Y8 nanoparticles, through PTT/PDT, could eradicate tumor cells and release damage-associated molecular patterns like HMGB1 antigens. These were effectively captured by dendritic cells and presented to T cells, igniting a specific immune cascade that led to a more potent synergistic anticancer therapy. In a murine tumor model, Y8 nanoparticles effectively modulated the immune microenvironment of metastatic tumors, invigorated the systemic antitumor immune response, and impeded the growth of metastatic lesions. This pioneering work integrates PTT, PDT, and immunotherapy into a cohesive framework, proposing a novel, safe, and highly effective therapeutic strategy with the potential to reduce treatment burdens while delivering transformative outcomes in cancer care.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 24. (a) Fabrication of Y8 NPs and in vivo validation of dual-mode imaging/PTT/PDT/photoimmunotherapy after Y8 NPs injection. (b) Cellular apoptosis and HMGB1 fluorescence staining images of tumor cells. (c) Primary and metastasis tumor growth and the relative serous cytokines of mice in different groups after treatments. (d) H & E staining of primary and metastasis tumors and CD8 fluorescence images of metastasis tumor tissues. Reproduced with permission [43]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. | |

Ji et al. [54] advanced this field by selecting DTPC–N2F, a photosensitizer with outstanding dual type Ⅰ/Ⅱ PDT and PTT performance (PCE = 67.94%), and combining it with a clinical-grade aluminium adjuvant gel to forge a novel photoimmunotherapy strategy for cervical cancer (Fig. 25). The nanoparticles were encapsulated with cell membranes derived from mouse cervical cancer U14 cells, thus enhancing the precision of their homologous targeting. The co-administration with the aluminium adjuvant gel induced a sustained form of immunogenic cell death (ICD), yielding synergistic antitumor therapeutic effects, fostering immune memory, and enhancing systemic antitumor immune responses, thereby effectively inhibiting the growth of peritoneal metastases. This strategy demonstrated significant inhibition of both primary and metastatic tumors in situ and within a peritoneal metastatic cervical cancer animal model, offering innovative perspectives on the comprehensive treatment of early and advanced stages of cervical cancer.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 25. (a) Schematic diagram of photoimmunotherapy for in situ cervical cancer treatment using DNPs@CM+Alum. (b) Quantification of FCM analysis of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells (CD3+ CD8+) and CD4+ T cells (CD3+ CD4+) in different treatment groups (n = 3). (c) Quantification of FCM analysis of CD8+ T cells (CD3+ CD8+) and CD4+ T cells (CD3+ CD4+) in the spleens of different treatment groups (n = 3). (d) FCM analysis of memory cells in the spleen (CD3+ CD8+ CD44+ CD62L− and CD3+ CD8+ CD44+ CD62L+) (n = 3) and the tumor-infiltrating memory T cells (CD3+ CD8+ CD44+) (n = 3). The data are presented as the mean ± SD. The p values were calculated using two-tailed unpaired t-tests or one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Reproduced with permission [54]. Copyright 2024, John Wiley and Sons. | |

The organismic response to elevated temperatures is frequently characterized by the induction of heat shock proteins (HSPs), which represent an endogenous defense mechanism against the harmful effects of heat stress [116,117]. The targeted inhibition of HSP synthesis represents a strategic approach to attenuating the thermotolerance of tumor cells, thereby facilitating their selective destruction at lower temperatures while preserving the integrity of normal tissue cells. Quercetin (Qu), a natural phytochemical with a favorable safety profile, has emerged as an effective modulator of HSP70 expression, a key HSP subtype, which significantly enhances the efficacy of mild PTT [118-120]. Inspired by these insights, Cai et al. [25] integrated Qu, a potent inhibitor of HSP activity, with IDIC to synthesize IDIC-Qu NPs (Fig. 26). These novel NPs demonstrate tunable photothermal properties, effectively suppressing HSP70 expression and orchestrating the in vivo ablation of tumors through a mild PTT regimen. This innovative multi-component encapsulation strategy not only enriches the spectrum of organic phototherapeutic nanoplatforms but also paves the way for expanded clinical applications of NFAs, heralding a new era of potential in oncology.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 26. (a) Synthesis process and schematic illustration of IDIC-Qu for enhanced cancer PTT. (b) Temperature variation of IDIC-Qu NPs for four cycles of repeated 660 nm laser irradiation (switch on/off) and the linear data obtained from the cooling period. (c) The expressions of HSP70 and HSP90 in 4T1 cells after different treatments were detected by Western blot (L is the abbreviation of laser). (d) Thermogram, tumor growth and weight changes of tumor-bearing mice and the digital photographs of the corresponding tumor after treatments. Reproduced with permission [25]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier. | |

The aqueous solubility of the majority of organic photosensitizers, including NFAs, represents a significant challenge that limits their bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy in biological systems. To address this issue, amphiphilic nanocarriers are increasingly employed for encapsulation, yielding NPs with enhanced water solubility. This encapsulation not only improves the dispersion of hydrophobic agents but also extends their systemic circulation time, thereby amplifying their diagnostic and therapeutic impact. With the evolution of nanocarrier technology, these vehicles have transcended their initial role, now offering functionalities such as chemotherapeutic co-delivery and organelle-specific targeting [121-123]. The convergence of phototherapeutic agents with these advanced nanocarriers to form NPs has become a streamlined and efficacious strategy for the design of a next-generation diagnostic and therapeutic platform with holistic performance.

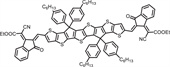

Distinguished from the traditional DSPE-PEG2000 nanocarrier, polyethylene glycol-functionalized pillararenes are characterized by their facile modification, straightforward synthesizability, and innate water solubility. They are capable of self-assembly into supramolecular vesicles with abundant cavities, providing an ideal environment for the encapsulation of photosensitizers. In 2022, Yao et al. [34] reported a pioneering work on utilizing the PEGylated amphiphilic pillararene WP5–2PEG, exploiting the self-assembled supramolecular vesicles for the encapsulation of DPIC, achieving a remarkable drug loading capacity of 69.5% (Fig. 27a). The supramolecular nano-drug DPIC NPs thus constructed are capable of orchestrating a synergistic therapeutic approach that integrates PTT and type Ⅰ/Ⅱ PDT, introducing innovative possibilities for the selection of nanocarriers in this field.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 27. (a) Schematic illustration of DPIC NPs and the application. Reproduced with permission [34]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. (b) Chemical structures of F8CA5 and WP5−2PEG−2TPP and the phototheranostics application of F8CA5 NPs. Reproduced with permission [31]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. (c) Schematic illustration of one-for-all phototheranostic nanoparticles for NIR-Ⅱ/IR thermal imaging guided mitochondria-targeting phototherapy. Reproduced with permission [20]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier. | |

Inspired by the modifiable side chains of aromatic hydrocarbons, Yao et al. [31] further enhanced WP5–2PEG by integrating triphenylphosphonium cations (TPP, a mitochondria-targeting moiety) onto the side chain of WP5–2PEG, yielding a mitochondria-targeted nanocarrier WP5–2PEG-2TPP (Fig. 27b). This novel nanocarrier facilitates the precise delivery of the photosensitizer F8CA5 to the mitochondria, enabling mitochondria-targeted FLI-guided dual phototherapy. The TPP functionalization approach for nanocarriers has been demonstrated to be broadly applicable to other nanocarrier systems. Fan et al. [20] selected an amphiphilic copolymer TPP-PEG-PPG-PEG-TPP, which is TPP-functionalized, to encapsulate the photosensitizer molecule IPIC, which possesses attributes of both PTT and PDT, thereby enabling precise mitochondrial targeting for precision theranostics (Fig. 27c). Collectively, these studies have illuminated a novel trajectory for the construction of multifunctional phototherapeutic agents with organelle-targeting capabilities, heralding a new frontier in targeted oncologic therapies.

6. Conclusions and prospectiveThe rapid development of NFAs has emerged as an efficient catalyst for significant advancements in the field of organic photovoltaics and has concurrently facilitating their integration into phototheranostics. The superior light absorption characteristics and the malleability of energy levels within NFAs are instrumental in enhancing the efficiency of photoelectric conversion, which is a keystone for the development of potent phototheranostic agents. This enhancement in light absorption not only improves therapeutic efficacy but also reduces the necessary light exposure duration, thereby improving patient comfort and increasing the safety of treatment. In the field of cancer diagnosis, the fluorescent attributes of NFAs can be strategically harnessed to fabricate exquisitely sensitive fluorescent probes. These probes, known for their selective accumulation in tumor tissues, facilitate real-time monitoring of tumor status through FLI, thereby revealing unprecedented opportunities for early diagnosis and intervention.

This review undertakes a systematic approach to synthesize the various NFAs-based phototheranostic agents that have emerged over recent years, with a particular focus on the influence of molecular architecture on performance. It is noteworthy that: (1) The expansion of π-conjugation or the fortification of D-A interactions can amplify the ICT effect, thereby promoting red-shifted absorption. (2) Enhancement of intramolecular rotation or the invocation of TICT can augment the potency of PTT. (3) Modulation of molecular stacking can enhance the efficacy of PDT. (4) Adjustments in energy levels can reinforce Type Ⅰ PDT activity. (5) Modifications to π-bridges or atomic programming can mitigate intermolecular π-π interactions or quench the TICT of excited states, augmenting the fluorescence quantum yield and, consequently, enhancing FLI performance. However, a complex interplay of energies exists among the aforementioned imaging and therapeutic modalities, presenting a formidable challenge to balance. In response, we have encapsulated the extant strategies for augmenting comprehensive diagnostic and therapeutic performance based on NFAs, which predominantly include: (1) Molecular engineering strategies, (2) The amalgamation with immunotherapy, (3) The encapsulation of multiple components, (4) The conjugation with functional nanocarriers. NFAs, as emerging drug carriers or targeted therapeutic agents, offer the promise of innovatively optimizing the diagnostic and therapeutic profiles of these materials through chemical structural design or the construction of drug delivery platforms. Furthermore, they have the potential to enhance biocompatibility and pharmacokinetic properties, thereby opening up broad prospects for their application in cancer treatment.

Despite the promising advancements in the utilization of NFAs in phototheranostics, significant obstacles remain for clinical translation. In this paper, we highlight several key issues and suggest potential solutions for addressing these challenges: (1) The cost and complexity of synthesis. While the exploitation of intramolecular non-covalent interactions can mitigate the closure reactions in synthesis and reduce costs, the traditional condensed NFAs, with their expansive ring skeletons, inevitably elevated synthesis complexity, purification challenges, and cost. (2) Safety and side effects. Although NFAs-based nanoparticles can be rationally designed to exhibit high targeting specificity, the long-term safety of their application necessitates further validation. Additionally, the control and prevention of potential novel side effects are imperative. (3) Biocompatibility and stability. In the complex environment of blood circulation, the corresponding nanomaterials must exhibit robust stability, minimal leakage, and ensure therapeutic efficacy at the tumor site post-decomposition. In nanobiomedicine, the long-term stability of materials is non-negotiable to guarantee treatment efficacy. (4) The complexity of the tumor microenvironment. Shifts in the tumor microenvironment, such as the epithelial-mesenchymal transition, can influence tumor aggressiveness, metastatic potential, and treatment response. (5) AI-assisted design. NFAs encounter challenges in the AI-assisted design of nanobiomaterials, including molecular representation and optimization, the precision and reliability of machine learning models, and the openness of datasets and tools. However, with the relentless refinement and progression of AI technologies, these hurdles will be overcome, opening up new avenues for the application of NFAs. In conclusion, NFAs hold immense potential in the field of cancer treatment as well as encountering many challenges in future development. Through continued research and technological innovation, these challenges can be overcome, paving the way for the emergence of a new generation of high-performance clinical photodiagnostic agents.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statementYaojun Li: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. Yun Li: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. Shenglong Liao: Writing – review & editing. Yang Li: Writing – review & editing. Shouchun Yin: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (Nos. LZ23B040001, LY23E030003 and LY24B030005), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22105222), the Interdisciplinary Research Project of Hangzhou Normal University (No. 2024JCXK05) and the Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Advanced Functional Polymer Design and Application, Soochow University.

| [1] |

R.L. Siegel, K.D. Miller, N.S. Wagle, A. Jemal, CA Cancer J. Clin. 73 (2023) 17-48. DOI:10.3322/caac.21763 |

| [2] |

R.L. Siegel, A.N. Giaquinto, A. Jemal, CA Cancer J. Clin. 74 (2024) 12-49. DOI:10.3322/caac.21820 |

| [3] |

H. Stower, Nat. Med. 26 (2020) 1804-1805. DOI:10.1038/s41591-020-01151-2 |

| [4] |

M. Ghasemlou, N. Pn, K. Alexander, et al., Adv. Mater. 36 (2024) e2312474. |

| [5] |

A. Pulumati, A. Pulumati, B.S. Dwarakanath, Cancer Rep. 6 (2023) e1764. |

| [6] |

J.S.J. Britto, X. Guan, T.K.A. Tran, et al., Small Sci. 4 (2024) 2300221. |

| [7] |

Y. Dai, H. Zhao, K. He, et al., Small 17 (2021) e2102527. |

| [8] |

L. Wang, N. Li, W. Wang, et al., ACS Nano 18 (2024) 4683-4703. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.3c12316 |

| [9] |

S. Wang, W.X. Ren, J.T. Hou, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 50 (2021) 8887-8902. DOI:10.1039/d1cs00083g |

| [10] |

B. Nasseri, E. Alizadeh, F. Bani, et al., Appl. Phys. Rev. 9 (2022) 011317-011320. |

| [11] |

V.N. Nguyen, Z. Zhao, B.Z. Tang, J. Yoon, Chem. Soc. Rev. 51 (2022) 3324-3340. DOI:10.1039/d1cs00647a |

| [12] |

V.V. Brus, J. Lee, B.R. Luginbuhl, et al., Adv. Mater. 31 (2019) e1900904. |

| [13] |

J. Wang, P. Xue, Y. Jiang, Y. Huo, X. Zhan, Nat. Rev. Chem. 6 (2022) 614-634. |

| [14] |

C. Zhu, J. Yuan, F. Cai, et al., Energy Environ. 13 (2020) 2459-2466. DOI:10.1039/d0ee00862a |

| [15] |

Y. Cui, H. Yao, J. Zhang, et al., Adv. Mater. 32 (2020) e1908205. |

| [16] |

A. Armin, W. Li, O.J. Sandberg, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 11 (2021) 20003570. |

| [17] |

Y. Cai, Z. Wei, C. Song, et al., Chem. Commun. 55 (2019) 8967-8970. DOI:10.1039/c9cc04195h |

| [18] |

G. Zhang, W. Wang, H. Zou, et al., J. Mater. Chem. B 9 (2021) 5318-5328. DOI:10.1039/d1tb00659b |

| [19] |

C. Li, G. Jiang, J. Yu, et al., Adv. Mater. 35 (2023) e2208229. |

| [20] |

Q. Wang, J. Xu, R. Geng, et al., Biomaterials 231 (2020) 119671. |

| [21] |

H. Chen, S. Yan, L. Zhang, et al., Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 405 (2024) 135346. |

| [22] |

J. Xia, H. Quan, Y. Huang, et al., ACS Macro Lett. 13 (2024) 489-494. DOI:10.1021/acsmacrolett.4c00031 |

| [23] |

K. Yang, Z. Zhang, Y. Gan, et al., J. Mater. Chem. B 10 (2022) 7622-7627. DOI:10.1039/d2tb00984f |

| [24] |

Y. Yuan, Z. Feng, S. Li, et al., Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) e2201263. |

| [25] |

W. Fan, Y. He, P. Hu, et al., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 670 (2024) 762-773. |

| [26] |

D. Li, Y. Li, Q. Wu, et al., Small 17 (2021) e2102044. |

| [27] |

X. Li, F. Fang, B. Sun, et al., Nanoscale Horiz. 6 (2021) 177-185. DOI:10.1039/d0nh00672f |

| [28] |

H. Yuan, Z. Li, Q. Zhao, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 33 (2023) 2213209. |

| [29] |

X. Li, L. Liu, S. Li, et al., ACS Nano 13 (2019) 12901-12911. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.9b05383 |

| [30] |

B. Lu, H. Quan, Z. Zhang, et al., Nano Lett. 23 (2023) 2831-2838. DOI:10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c00119 |

| [31] |

B. Lu, Y. Huang, H. Quan, et al., ACS Macro Lett. 12 (2023) 1365-1371. DOI:10.1021/acsmacrolett.3c00454 |

| [32] |

B. Lu, J. Xia, H. Quan, et al., Small 20 (2023) e2307664. |

| [33] |

L. Li, C. Shao, T. Liu, et al., Adv. Mater. 32 (2020) e2003471. |

| [34] |

B. Lu, Z. Zhang, Y. Ji, et al., Sci. China Chem. 65 (2022) 1134-1141. DOI:10.1007/s11426-022-1232-9 |

| [35] |

B. Lu, Z. Zhang, Y. Huang, et al., Chem. Commun. 58 (2022) 10353-10356. DOI:10.1039/d2cc03248a |

| [36] |

B. Li, Y. Gan, K. Yang, et al., Sci. Chin. Mater. 66 (2022) 385-394. |

| [37] |

Z. He, L. Zhao, Q. Zhang, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 30 (2020) 1910301. |

| [38] |

X.F. Zhu, C.C. Liu, Z.B. Hu, et al., Nano Res. 13 (2020) 2570-2575. DOI:10.1007/s12274-020-2901-y |

| [39] |

Y. Zhu, H. Lai, Y. Gu, et al., Adv. Sci. 11 (2024) e2307569. |

| [40] |

B. Lu, Z. Zhang, D. Jin, et al., Chem. Commun. 57 (2021) 12020-12023. DOI:10.1039/d1cc04629b |

| [41] |

Y. Cai, C. Tang, Z. Wei, et al., ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 4 (2021) 1942-1949. DOI:10.1021/acsabm.0c01576 |

| [42] |

M. Li, Z. Lu, J. Zhang, et al., Adv. Mater. 35 (2023) e2209647. |

| [43] |

C. Song, J. Ran, Z. Wei, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13 (2021) 3547-3558. DOI:10.1021/acsami.0c18841 |

| [44] |

H. Xiao, Y. Wang, J. Chen, et al., Adv. Healthc. Mater. 13 (2024) e2303183. |

| [45] |

Y. Zhu, H. Lai, H. Guo, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202117433. |

| [46] |

Z. Liu, J. Wen, G. Zhou, et al., Adv. Ther. 5 (2022) 2200168. |

| [47] |

S. Jia, Z. Li, J. Shao, et al., ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 4 (2022) 5275. DOI:10.1021/acsapm.2c00699 |

| [48] |

Y. Zhao, Y. Cui, S. Xie, et al., Biomater. Sci. 12 (2024) 4386-4392. DOI:10.1039/d4bm00605d |

| [49] |

K. Yang, B. Yu, W. Liu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107889-107894. |

| [50] |

Y.J. Li, J.T. Ye, Y. Li, et al., Polym. Chem. 14 (2023) 3008-3017. DOI:10.1039/d3py00461a |

| [51] |

Y. Gu, H. Lai, Z.Y. Chen, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202303476. |

| [52] |

K. Yang, F. Long, W. Liu, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14 (2022) 18043-18052. DOI:10.1021/acsami.1c22444 |

| [53] |

B. Yin, Q. Qin, Z. Li, et al., Nano Today 45 (2022) 101550. |

| [54] |

G. Niu, X. Bi, Y. Kang, et al., Adv. Mater. 36 (2024) 2407199. |

| [55] |

C. Xu, K. Pu, Chem. Soc. Rev. 50 (2021) 1111-1137. DOI:10.1039/d0cs00664e |

| [56] |

Y. Lu, M. Li, Adv. Funct. Mater. 34 (2024) 2312753. |

| [57] |

Y. Li, M. Jiang, M. Yan, et al., Coord. Chem. Rev. 506 (2024) 215718-215737. |

| [58] |

P. Cheng, Y. Yang, Acc. Chem. Res. 53 (2020) 1218-1228. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00157 |

| [59] |

D. Meng, R. Zheng, Y. Zhao, et al., Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) e2107330. |

| [60] |

X. Wan, C. Li, M. Zhang, Y. Chen, Chem. Soc. Rev. 49 (2020) 2828-2842. DOI:10.1039/d0cs00084a |

| [61] |

Y. Che, M.R. Niazi, R. Izquierdo, D.F. Perepichka, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 24833-24837. DOI:10.1002/anie.202109357 |

| [62] |

Y. Lin, J. Wang, Z.G. Zhang, et al., Adv. Mater. 27 (2015) 1170-1174. DOI:10.1002/adma.201404317 |

| [63] |

X.D. Zhang, H. Wang, A.L. Antaris, et al., Adv. Mater. 28 (2016) 6872-6879. DOI:10.1002/adma.201600706 |

| [64] |

Y. Su, B. Yu, S. Wang, H. Cong, Y. Shen, Biomaterials 271 (2021) 120717. |

| [65] |

Y. Maruoka, T. Nagaya, K. Sato, et al., Mol. Pharm. 15 (2018) 3634-3641. DOI:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00002 |

| [66] |

X. Yin, Y. Cheng, Y. Feng, et al., Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 189 (2022) 114483. |

| [67] |

J. Ma, X. Yang, Y. Sun, J. Yang, Sci. Rep. 9 (2019) 10987. |

| [68] |

Y.Y. Zhao, H. Kim, V.N. Nguyen, et al., Coord. Chem. Rev. 501 (2024) 215560-215573. |

| [69] |

S. Liu, X. Zhou, H. Zhang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 5359-5368. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b13889 |

| [70] |

Z. Zhao, C. Chen, W. Wu, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 768-778. |

| [71] |

X.W. Liu, W. Zhao, Y. Wu, et al., Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 3887-3894. |

| [72] |

S. Sasaki, G.P.C. Drummen, G.I. Konishi, J. Mater. Chem. C 4 (2016) 2731-2743. |

| [73] |

Q. Yang, Z. Hu, S. Zhu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 1715-1724. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b10334 |

| [74] |

D. Liese, G. Haberhauer, Isr. J. Chem. 58 (2018) 813-826. DOI:10.1002/ijch.201800032 |

| [75] |

Z.Z. Zou, H.C. Chang, H.L. Li, S.M. Wang, Apoptosis 22 (2017) 1321-1335. DOI:10.1007/s10495-017-1424-9 |

| [76] |

E. Pang, S.J. Zhao, B.H. Wang, et al., Coord. Chem. Rev. 472 (2022) 214780-214795. |

| [77] |

Y. Cai, W. Si, W. Huang, P. Chen, J. Shao, et al., Small 14 (2018) e1704247. |

| [78] |

X. Li, N. Kwon, T. Guo, Z. Liu, J. Yoon, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 11522-11531. DOI:10.1002/anie.201805138 |

| [79] |

S. Liu, H. Zhang, Y. Li, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 15189-15193. DOI:10.1002/anie.201810326 |

| [80] |

X. Wang, Y. Song, G. Pan, et al., Chem. Sci. 11 (2020) 10921-10927. DOI:10.1039/d0sc03128c |

| [81] |

L. Huang, D. Qing, S. Zhao, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 430 (2022) 132638-132642. |

| [82] |

Y. Yu, S. Wu, L. Zhang, et al., Biomaterials 280 (2022) 121255. |

| [83] |

Z. Zhuang, J. Li, P. Shen, Z. Zhao, B.Z. Tang, Aggregate 5 (2024) e540. |

| [84] |

A. Huang, L. Su, Acc. Mater. Res. 4 (2023) 729-732. DOI:10.1021/accountsmr.3c00098 |

| [85] |

Z. Zhao, S. Lei, M. Zeng, M. Huo, Aggregate 5 (2023) e418. |

| [86] |

S.A. Chen, T.H. Jen, H.H. Lu, J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 57 (2013) 439-458. DOI:10.1007/978-1-4614-3320-0_27 |

| [87] |

P. Shen, H. Liu, Z. Zhuang, et al., Adv. Sci. 9 (2022) 2200374. |

| [88] |

Y. Tian, D. Yin, L. Yan, WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 15 (2023) e1831. |

| [89] |

G. Han, T. Hu, Y. Yi, Adv. Mater. 32 (2020) 2000975. |

| [90] |

S. Song, Y. Zhao, M. Kang, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 31 (2021) 2107545. |

| [91] |

Y. Jin, Q.C. Peng, S. Li, et al., Natl. Sci. Rev. 9 (2022) nwab216. |

| [92] |

J. Xia, S. Xie, Y. Huang, X.X. Wu, B. Lu, Chem. Commun. 60 (2024) 8526-8536. DOI:10.1039/d4cc02596b |

| [93] |

Y. Wan, L.H. Fu, C. Li, J. Lin, P. Huang, Adv. Mater. 33 (2021) e2103978. |

| [94] |

L. Huang, S. Zhao, J. Wu, et al., Coord. Chem. Rev. 438 (2021) 213888-213908. |

| [95] |

B. Lu, L. Wang, H. Tang, D. Cao, J. Mater. Chem. B 11 (2023) 4600-4618. DOI:10.1039/d3tb00545c |

| [96] |

K.X. Teng, W.K. Chen, L.Y. Niu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 19912-19920. DOI:10.1002/anie.202106748 |

| [97] |

K.X. Teng, L.Y. Niu, Q.Z. Yang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145 (2023) 4081-4087. DOI:10.1021/jacs.2c11868 |

| [98] |

X. Hu, Z. Fang, F. Sun, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63 (2024) e202401036. |

| [99] |

Z. Hu, C. Fang, B. Li, et al., Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4 (2020) 259-271. |

| [100] |

Q. Ma, X. Sun, W. Wang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 1681-1692. |

| [101] |

W. Zhang, X. Du, Y. Ma, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 34 (2023) 2308591. |

| [102] |

Z. Wang, M. Zhang, S. Chi, et al., Adv. Healthc. Mater. 11 (2022) e2200521. |

| [103] |

F. Zhao, X. Zhang, F. Bai, et al., Adv. Mater. 35 (2023) e2208097. |

| [104] |

H. Ren, J. Li, J.F. Lovell, Y. Zhang, Coord. Chem. Rev. 503 (2024) 215634-215653. |

| [105] |

Y. Dai, Z. Sun, H. Zhao, et al., Biomaterials 275 (2021) 120935. |

| [106] |

S. Song, Y. Zhao, M. Kang, et al., Adv. Mater. 36 (2024) e2309748. |

| [107] |

N. Liang, D. Meng, Z. Wang, Acc. Chem. Res. 54 (2021) 961-975. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00677 |

| [108] |

X. Zhao, F. Zhang, Z. Lei, Chem. Sci. 13 (2022) 11280-11293. DOI:10.1039/d2sc03136a |

| [109] |

H. Li, Q. Li, Y. Gu, et al., Aggregate 5 (2024) e528. |

| [110] |

S. Yang, G.L. Wu, N. Li, et al., J. Nanobiotechnol. 20 (2022) 475. |

| [111] |

S. Yang, B. Sun, F. Liu, et al., Small 19 (2023) e2207995. |

| [112] |

J. Ye, Y. Yu, Y. Li, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16 (2024) 34607-34619. DOI:10.1021/acsami.4c05334 |

| [113] |

P. Hu, X. Peng, S. Zhao, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 492 (2024) 152033. |

| [114] |

W. Li, T. Ma, T. He, Y. Li, S. Yin, Chem. Eng. J. 463 (2023) 142495. |

| [115] |

T. Ma, W. Li, J. Ye, et al., Nanoscale 15 (2023) 16947-16958. DOI:10.1039/d3nr03881e |

| [116] |

K. Yang, S. Zhao, B. Li, et al., Coord. Chem. Rev. 454 (2022) 214330. |

| [117] |

Z. Chen, S. Li, F. Li, et al., Adv. Sci. 10 (2023) e2206707. |

| [118] |

X. He, S. Zhang, Y. Tian, W. Cheng, H. Jing, Int. J. Nanomed. 18 (2023) 1433-1468. DOI:10.2147/ijn.s405020 |

| [119] |

W. Wang, J. Yu, Y. Lin, et al., Biomater. Adv. 149 (2023) 213418. |

| [120] |

B. Li, G. Fu, C. Liu, et al., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 665 (2024) 389-398. |

| [121] |

J. Li, K. Kataoka, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 538-559. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c09029 |

| [122] |

P. Wen, W. Ke, A. Dirisala, et al., Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 198 (2023) 114895. |

| [123] |

C. He, P. Feng, M. Hao, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 34 (2024) 2402588. |

2025, Vol. 36

2025, Vol. 36