b National Engineering Laboratory for VOCs pollution Control Material & Technology, Research Center for Environmental Material and Pollution Control Technology, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 101408, China;

c College of Resources and Environment, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 101408, China

As volatile organic compounds (VOCs) pose such a high risk to human health and air pollution, their elimination has been the subject of substantial research [1-3]. Being one of the most common types of oxygenated volatile organic compounds (OVOCs), vinyl acetate (VAE) has long served as a forerunner to organic adhesives in the printing and packaging sectors. VAE is flammable, poisonous, and polymerizable, all of which pose a concern to the environment and human health, even at low levels. However, the effect on the environment and the eradication of VAE were hardly ever investigated. It is vital to design functional catalysts with excellent catalytic oxidation activity, which has not yet been documented for VAE catalytic oxidation, and heterogeneous catalytic oxidation techniques have been a topic of interest for low temperature disposal of environmental persistent pollutants [4,5].

Supported noble-metal catalysts and transition metal oxide catalysts are two examples of catalytic design strategies described in the literature for the removal of environmental contaminants [6]; [7]. The deep oxidation process is well known to benefit greatly from supported noble metal catalysts [8,9]. However, manganese oxide is the focus of most VOCs catalytic oxidation research [10-14] due to its abundance, low toxicity, numerous coordination numbers, oxidation states, high redox potential, high structural flexibility, environmental friendliness, and low cost [15].

The basic structural motifs of manganese oxides are [MnO6] octahedra that share corners and edges [16,17]. This allows for the construction of the tunnel and layer-linked structures in a variety of dimensions [18], including cross-linked structures [19] and layered structures [20-22], depending on the synthetic conditions. Also, the morphologies of urchins, rods, and flowers can be seen in manganese oxides [23,24]. Many studies have been performed to learn more about the connections between structural features and catalytic activity. Research findings suggest that the presence of oxygen vacancies (Vo) would alter the initial charge distribution of the catalyst, improving its catalytic activity, and have found that the cross-linked structural MnO2 highly depends on the density of oxygen vacancies [25,26]. Thus, increasing oxygen vacancy is considered a useful tactic for boosting catalytic performance [27,28]. To effectively manage VAE oxidation, it is crucial to identify and precisely regulate the catalytic sites and types involved.

This research examines the correlation between edging/corner-connected MnO6 structural motifs and oxygen vacancies in multi-dimensional manganese oxides to shed light on the defect sites and reaction mechanisms for VAE catalytic oxidation over manganese oxide. Extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), X-ray powder diffraction (XRD), and density functional theory were utilized to investigate the coordination mode, Mn–O property, defects formation, and structural motif compatibility between layered and cross-linked structures of manganese oxide (DFT). Chemical adsorption-mass spectrometry (TPX-MS), ex/in situ Raman spectroscopy, and in situ diffuse reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy are all used to rigorously verify and examine the reaction mechanism, kinetics, and mineralization process (DRIFT). Finally, a general law of catalytic oxidation VAE pollution was established.

Characterization of structure and morphology: The diffraction peaks of OMS-2, β-MnO2, δ-MnO2 and γ-MnO2 correspond to Cryptomelane (PDF #29-1020), Pyrolusite (PDF #24-0735), Birnessite (PDF #43-1456) and Nsutite (PDF #17-0510), respectively (Fig. S1a in Supporting information) [29]. After the catalytic process, the original structure of the catalyst remained unchanged, as shown by the findings (Fig. S1b in Supporting information). The OMS-2 (2 × 2, 1 × 1), β-MnO2 (1 × 1) and γ-MnO2 (2 × 1, 1 × 1) contained a significant fraction of corn-sharing Mn octahedra (mono- and di-m-oxo-bridged Mn ions) was observed (Figs. 1a–c), which resulted in the formation of different cross-linked structures, including the edge-sharing (di-m-oxo-bridged) and/or corner-sharing (mono-m-oxo-bridges) [MnO6] structural motifs. The δ-MnO2 has a layered structure composed predominantly of edge-sharing [MnO6] octahedra (di-m-oxo-bridged) (Fig. 1d). All MnO2 polymorphs have the same fundamental atomic structure, which consists of tiny Mn4+ ions in a spin-polarized 3d3 configuration and big, highly polarizable O2− ions in a spin-unpolarizable 2p6 configuration, both of which are organized in corner- and edge-sharing [MnO6] octahedra [30]. Moreover, Fig. 1 and Fig. S2 (Supporting information) displayed visual representations of various cross-linked structures (supporting information). However, both cross-linked structural MnO2 samples were exhibited as nanorods of varying sizes. The OMS-2 sample measured between 13 and 33 nm in diameter and between 70 and 270 nm in length. The lengths of the β-MnO2 nanorods were 400–800 nm, while their diameters were 30–90 nm. The urchin-like structures in the γ-MnO2 sample were 8–12 nm in diameter and 50–80 nm in length. The nanoplate-based flower-shaped microspheres of layered-linked structural δ-MnO2 were provided as a contrast to the cross-linked structural MnO2. Amorphous manganese oxide (AMO) is shown in Fig. 1e, revealing its particle and non-crystal structure. Fig. S3 and Table S1 (Supporting information) of the supplementary materials illustrate the MnO2 phase configurations and their corresponding pore sizes, respectively. These findings are strongly connected to the various interlinking mechanisms of MnO6 octahedral in the MnO2 structure. All the manganese oxides exhibit a typical IV isotherm, and the varied pore size distribution features have been determined. The increased SBET (92 m2/g) and pore volume (0.359 cm3/g) of OMS-2 catalysts are attributed as advantageous variables for VAE catalytic oxidation.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. The images of (a) OMS-2, (b) β-MnO2, (c) γ-MnO2, (d) δ-MnO2, and (e) AMO. | |

Coordination structure and chemical states: Fig. 2 illustrates, on an atomic scale, the structural properties shared by a variety of catalytic active oxides. The X-ray absorption near-edge structure area is very sensitive to the average oxidation state as well as the local coordination geometry [31,32]. Fig. 2a shows that the oxidation states of OMS-2 and β-MnO2 catalysts are intermediate, while those of AMO δ-MnO2 are the lowest and highest, respectively, because of their saturated and undersaturated microstructures. The average oxidation state of OMS-2 and δ-MnO2 was 3.52 and 3.48, respectively, based on the Mn K-edge X-ray absorption of standard manganese oxides calibration curve [33]. This indicates that both the OMS-2 and δ-MnO2 catalysts are unsaturated in their coordination, which leads to a propensity to produce defects. The finding is in excellent accord with the Mn oxidation state previously obtained by XPS analysis. It has been shown that EXAFS can provide quantitative structural information on the atom level (Fig. 2b). δ-MnO2 is composed of an edging-sharing MnO6 octahedron. Two typical strong Fourier transformed peaks were found, one at R of ~1.5 Å, which is typical for 6-fold oxygen coordinated Mn4+ ions, and the other at around 2.5, which is connected to di-m-oxo-bridged Mn4+ ions. For OMS-2, in addition to the peaks at R of ~1.5 Å and 2.5 Å, there is also a prominent third peak at R of ~3.0 Å, which may be attributed to corner-connected Mn ions and comprises a sizeable portion of corner-sharing Mn octahedra leading to tunnel formation. The MnO6 structural motifs in the OMS-2 catalyst are both corner and edge linked. Nevertheless, unlike the structural properties of δ-MnO2, the structural characteristics of β-MnO2 catalyst were dominated by corner-sharing MnO6 (R of ~3.0 Å). Fig. 2c shows the standard k EXAFS data that was done on all the samples, and Table S2 (Supporting information) has a listing of the EXAFS structural parameters. Most of the Mn—O distances were found to be close to 1.9 Å, which is a value that is typical for the Mn4+O6 octahedra that were presented. It has been discovered that the Mn–Mn distances are quite near to 3.0 Å Likewise for OMS-2, the Mn—O coordination number is much lower (4.9) when compared to the comparable values for δ-MnO2 (5.2) and β-MnO2 (5.7), which suggests that there are oxygen defect sites in OMS-2. The findings give strong evidence for the existence. As illustrated in Figs. 2d–f and Fig. S4 (Supporting information), the chemical states of MnO2 catalysts were more crucial than bulk structure characteristics. Table S3 (Supporting information) provides a summary of a quantitative investigation of surface Mn3+/Mn4+ molar ratios. The molar ratio of surface Mn3+/Mn4+ is greater for cross-linked structural OMS-2 than for layered-linked structural δ-MnO2 and non-crystal AMO, according to the findings of a comprehensive study. To maintain the electrostatic equilibrium, a lower state of manganese (Mn3+) that is present on the surface of the catalyst will create Vo [34]. Since manganese oxide materials exhibit Mn3+(d4) in MnO6 structural motifs with longer Mn—O bonds than Mn4+(d3), the presence of Mn3+ chemical states may effectively weaken Mn—O bonds. The Mn3+—O in MnO6 octahedra at the catalyst's surface are more active owing to the flexible oxygen mobility. This is because the Jahn-Teller effect will boost the mobility of oxygen species. Moreover, the surface average Mn chemical state (AOS) was also measured [35]. The determined Mn AOS values for all the MnO2 samples are shown below, which correlate very well with the presence of Mn3+ and defect sites. We also measured the O 1s XPS to see whether there was any correlation between the chemical states and the defect locations (see Fig. 2 and Table S3 for more information). It is possible to fit a curve with two components that have binding energy values of 529.8 and 531.7 eV. The first component has a form that is typical of lattice oxygen (Olatt), while the second component is attributed to oxygen that is chemically absorbed on oxygen vacancies or low-coordination surface oxygen species (Oads). According to the results obtained, the Oads/Olatt molar ratio was found to be greater in the cross-linked structural OMS-2 samples than in the layered-linked structural δ-MnO2 samples. These structural characteristics may help to enhance catalytic performance in deep oxidation processes [36].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) Mn K-edge XANES spectra; (b) magnitude of k2-weighted Fourier transforms of Mn K-edge EXAFS spectra; (c) Mn K-edge EXAFS oscillation function for different catalysts, and XPS spectra in the (d) Mn2p, (e) Mn 3s, and (f) O1s region of catalysts. | |

Chemical properties and functional characteristics: In catalytic oxidation of organic molecules, oxygen mobility and reducibility of the catalyst are also essential. The H2-TPR profiles of the as-prepared MnO2 catalysts are shown in Fig. 3a. The reduction peaks of each MnO2 species partially overlapped, which was ascribed to the reduction of MnO2 to MnO through Mn2O3 and/or Mn3O4. Comparing the data obtained from various crystallographic structures of MnO2, β-MnO2 exhibited a wide peak at 406 ℃ and 549 ℃. γ-MnO2 exhibited a similar pattern with peaks located at 395 ℃ and 511 ℃, and the lower temperature peak is compatible with the conversion of MnO2 to Mn3O4, and subsequently Mn3O4 to MnO. Yet, OMS-2, δ-MnO2, and AMO exhibited two overlapping reduction peaks, proving the presence of separate MnO2 reduction pathways. Moreover, it was shown that OMS-2 catalysts had the most mobile oxygen species, both on their surface and in their bulk, as measured by the temperature at which their reduction peak position dropped to a lower value. Moreover, the quantities of H2 used were computed and presented in Table S4 (Supporting information), with the theoretical H2 consumption for the reduction of MnO2 to Mn3O4 and Mn3O4 to MnO being 7.67 mmol/g and 4.37 mmol/g, respectively. Nevertheless, each H2 consumption of MnO2 was slightly less than the predicted quantity of H2 required for the reduction of MnO2 to MnO, indicating the presence of a significant proportion of Mn3+. Furthermore, Fig. 3b's comprehensive findings demonstrate that O2-TPD-MS exhibits the capacity to transmit and migrate oxygen species. This capability may be broken down into three categories. At first, observations were made of the adsorbed oxygen species (Ⅰ) and the surface labile lattice oxygen (Ⅱ), which consisted of O2−, O−, and O2−. These observations were made at temperatures that were rather low. The peak (Ⅲ) is subsequently identified as the bulk lattice oxygen (O2−) [37]. In the meanwhile, the capacity of oxygen species is determined by integrating the area of the O2-TPD-MS curves; the OMS-2 has more surface oxygen species that are loosely bound than δ-MnO2. Compared to the layered-linked structural MnO2 catalyst, which only had edge-connected Mn ions, the cross-linked structural OMS-2 with both corner- and edge-connected MnO6 structural motifs led to a reduction peak at a lower temperature and had numerous mobile oxygen species at their surface.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) H2-TPR, (b) O2-TPD-MS, (c) NH3-TPD-MS, (d) pyridine-IR at 100 ℃, (e) vinyl acetate-TPD profiles and (f) summarized results of different MnO2. | |

This study used NH3-TPD-MS to investigate the hypothesis that differences in MnO2 surface acidity are caused by basic MnO6 structural motifs related to corner- and/or edge-sharing (Fig. 3c and Table S5 in Supporting information). Desorption of NH4+ weakly linked to surface hydroxyls accounts for the low-temperature desorption peak below 200 ℃, whereas the peak at 320 ℃ and 450 ℃ corresponds to the medium and strong acidic sites and is attributed to the desorption of NH3 firmly bound to surface corner- and/or edge-connected Mn ions. The percentage of cross-linked structural MnO2 at medium acid sites was found to be higher than that of layered-linked structural δ-MnO2 and AMO. The order was: OMS-2 (28.7%) > AMO (7.7%) > δ-MnO2 (2.0%). The pyridine adsorbed infrared (Py-IR) was subsequently performed (Fig. 3d) to reveal the acidic kinds and quantities of surface acid sites. The findings demonstrate that the amount of Lewis acid of δ-MnO2 is larger than that of OMS-2, and that there are no acid sites for β-MnO2. Meanwhile, the desorption of VAE over the middle strong acid sites, which refer to the corner- and/or edge-connected Mn ions sites and/or defect sites of MnO2's surface, revealed that cross-linked structural MnO2 presented a higher desorption ability of VAE than that of δ-MnO2. This was evident in the VAE-TPD profiles (Fig. 3e). These variations may influence the distribution of byproducts and the tautomerism of the catalytic process. Finally, the cross-linked structural OMS-2 sample exhibited greater abundances of reducibility, middle strong acid sites (unsaturated coordination Mn ions and/or defects sites), and oxygen species features than the layered-linked structural δ-MnO2 and non-crystal AMO samples (Fig. 3f). Differences in structure characteristics and catalytic activity may be traced back to the underlying structural variations between the layered-linked structural δ-MnO2 catalyst and the cross-linked structural OMS-2 catalyst, where MnO6 defect sites can be either corner- or edge-connected.

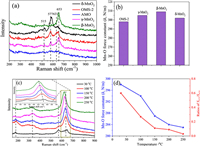

Chemical bond properties and defects: Fig. 4a displays the Raman spectra of MnO2 samples, which demonstrate how the varied connectivity of MnO6 structural motifs within these materials leads to distinct lattice vibrational characteristics. The Raman shift of cross-linked structural MnO2 was discovered to be identical. The OMS-2 type sample has a hollandite-type tunnel structure [38], and the Raman shift at 577 and 631 cm−1 derives from the symmetric stretching vibration of MnO6 groups. The β-MnO2 is a typical rutile-type compound with empty tunnels, distinguished by a Raman shift at 653 cm−1 with A1g symmetry. For γ-MnO2, the peaks at 570 cm−1 are ascribed to deformation modes of the metal-oxygen chain of Mn–O–Mn in the MnO2 lattice, while the peaks at 650 cm−1 are interpreted as Mn—O stretching modes. The layered-linked structural δ-MnO2 is composed of layered sheets of MnO6 structural motifs, with the Raman band at 631 cm−1 and 577 cm−1 attributable to the Mn—O stretching vibration in the basal plane of MnO6 sheets [39]. AMO samples containing no crystals exhibited a mild Raman shift.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (a) Raman spectra and (b) Mn-O bond force constant, (c) in situ Raman spectra and (d) oxygen vacancies properties of different manganese oxides. | |

The characteristics of the Mn—O bond were evaluated using the bond force constant (k), which was determined using an estimation based on Hooke's law [40]. The OMS-2 sample was shown the smallest of Mn—O force constant (Fig. 4b), which indicates that OMS-2 was found to have the greatest propensity of oxygen mobility when compared to that of δ-MnO2, which was then followed by γ-MnO2 and β-MnO2. Also, oxygen vacancies may be formed because of a weakening of the Mn—O bonds, which increases the mobility of oxygen. Fig. 4c shows the comprehensive findings of analyzing in situ Raman spectra to elaborate on the pattern of change in oxygen vacancies and Mn—O bond strength throughout a range of reaction temperatures. The relative strength of the peaks at 570 and 633 cm−1 [41] was correlated with the development of oxygen vacancy. Rising temperatures cause a decline in the ratio of S570 to S633, as seen in Fig. 4d. This indicates that the oxygen vacancies were used up throughout the course of the reaction, and that it was used to energies oxygen molecules in the gas phase. Moreover, when the reaction temperature rises from room temperature to 250 ℃, there is a minor change in the location of the 633 cm−1 peak towards a lower wave-number. Hooke's law was used to determine the Mn—O bond force constant (k) through the Raman shift; the data show that oxygen mobility increased in tandem with the appearance of vacancies in the Mn—O bond. The oxidation of VAE through catalysis is improved by its presence. Correlated with the MnO6 structural unit and defect formation: Defect formation energy of δ-MnO2 and OMS-2 was computed, as shown in Fig. 5, Fig. S5 (Supporting information), and Table S6 (Supporting information), to better understand the differences in the affinity of exposed facets of δ-MnO2 and OMS-2 in reactant molecule activation and its influence on contaminant oxidation. The formation energies of a single oxygen defect at the δ-MnO2 with edge-bridged MnO6 structural motifs were analyzed (Fig. 5a). As the formation energy of oxygen vacancies for (001) is considerably lower than that of (110) and (100), this indicates that it is simpler for oxygen vacancies to develop on (001) facets for δ-MnO2 [42]. The detailed findings showed that the formation energy of oxygen vacancies for (001) is much lower than that of (110). Defect formation energies were shown to be lower for δ-MnO2 compared to OMS-2 catalysts. Nevertheless, OMS-2 has generated two kinds of structural defect sites (VO-e and VO-c) with edge-connected MnO6 and corner-connected MnO6, respectively (Fig. 5b), these are more common than δ-MnO2 sites (edge-bridged MnO6). Results showed that VO-c oxygen vacancies were easier to generate than those of VO-c oxygen vacancies owing to their lower formation energy. The catalytic oxidation of OVOCs is significantly impacted by both VO-e and VO-c defects. As the oxidation of VAE depletes surface-active oxygen species, it is important to study the adsorption of O2 across the defect surface of the catalysts. Among the three-facet designed δ-MnO2, the (001) perfect facets display the maximum adsorption energy towards O2 (Fig. 5c). The oxygen-rich defect site (001) displays amazing power to activate oxygen molecules and to increase the catalytic oxidation performance of OVOCs. In the meanwhile, the defect facets showed more outstanding adsorption performance of O2 than that of the perfect facets. The identical experimental findings were also observed for the OMS-2 catalyst, as shown in Fig. 5d. The results showed that the defect facets displayed better adsorption performance of O2 than that of perfect facets, the VO-e was more readily adsorption of O2 than that of VO-e, and the oxygen-rich defect site facet has more advantages to adsorb O2 than that of other facets. This is because the oxygen-rich defect sites facet contains more oxygen. Both EXAFS analysis and catalytic activity tests demonstrated that the collaborative adsorption of OMS-2 with edging-sharing MnO6 structural defect sites and corner-sharing MnO6 defect sites was more favorable to the catalytic oxidation of VAE compared to δ-MnO2 adsorption at single defect sites.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Defect formation energy of (a) δ-MnO2 and (b) OMS-2; The oxygen molecules adsorption energy over defective manganese oxide of (c) δ-MnO2 and (d) OMS-2. | |

Fig. 6 displays the results of an analysis of VAE's catalytic efficiency. Maximum VAE conversion (T100 = 170 ℃) and CO2 yield (> 99%) are both shown by the OMS-2 nanorod (Figs. 6a and b). Furthermore, as shown in Figs. 6c and d, all the catalysts displayed high reactivity, with acetaldehyde and acetic acid being the main byproducts. VAE's conversion curves into acetaldehyde and acetic acid show the same tendency, increasing slowly at first, peaking at a higher temperature, and then declining quite quickly until the byproducts disappear at higher temperatures [43]. Figs. 6e and f depict the VAE product selectivity distribution across several MnO2 samples during catalytic oxidation at temperatures of 130 ℃ and 150 ℃, respectively. The higher values of acetic acid and acetaldehyde concentration were observed during VAE oxidation, the acetic acid concentration decreases in the order of cross-linked OMS-2 > non-crystal AMO > layered-linked δ-MnO2, the highest concentration for acetic acid reached 80 ppm (selectivity = 52%) for OMS-2 at 130 ℃, it means the ester bond of VAE was easier to break over cross-linked structural MnO2 than that of layered-linked δ-MnO2 due to the quantity difference of edge-connected MnO6 sites. Edge-connected MnO6 sites are the primary catalytic active sites to activate ester bond and to boost CO2 selectivity, as shown by the increase in CO2 yield (20% vs. 10%) and selectivity (75% vs. 31%) when comparing δ-MnO2 and OMS-2. The CO2 selectivity of δ-MnO2 is 79%, while the CO2 selectivity of OMS-2 is 93% when the reaction temperature is increased to 150 ℃, a highly sensitive temperature threshold to activate the corner-connected MnO6 sites, whereas the selectivity of the byproduct is less than 3%. Consequently, the synergistic impact of corner-connected and edge-connected MnO6 sites of OMS-2 was to increase the VAE catalytic activity while simultaneously inhibiting polymerization and the production of byproducts. Comparing the apparent activation energy (Ea) is another way to assess the catalytic activities of the MnO2 samples; the simpler it is to oxidize the VAE when the Ea value is lower [44]. Arrhenius plots for VAE oxidation at conversions below 20% are shown in Fig. S6 (Supporting information), good linear connections between plots of ln (r × 107) vs. 1000/T are achieved, and Ea values calculated from Arrhenius plot slopes are provided in Table S4. It is seen that the OMS-2 catalysts had a lower Ea value (44.10 kJ/mol) than other MnO2 samples, indicating that the activation of VAE on the surface of the OMS-2 catalyst occurs more readily at low temperatures. This was also confirmed by the byproduct distribution of catalytic oxidation VAE across the OMS-2 catalyst. Moreover, it demonstrated exceptional stability (Fig. S7 in Supporting information).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. (a) The light-off curves for the VAE oxidation. (b) Conversion to CO2 of catalysts for VAE catalytic oxidation. (c) Byproduct distribution of acetic acid. (d) Byproduct distribution of acetaldehyde. (e) Product selectivity distribution at 130 ℃. (f) Product selectivity distribution at 150 ℃. | |

Fig. 7 and Table S7 (Supporting information) show OMS-2 (Fig. 7a), γ-MnO2 (Fig. 7b), β-MnO2 (Fig. 7c) being used for in situ DRIFT of VAE catalytic oxidation over MnO2. Carboxyl (C═O) vibrations of carboxylic acid and ester (C═O—O—) were found at 1790 and 1775 cm−1, and these peaks were subsequently attributed to VAE. The vibration absorption strength of OMS-2 was clearly observed in comparison to β-MnO2 and γ-MnO2. Moreover, the OMS-2 adsorption performance did not weaken with the increase of adsorption and reaction temperature, indicating that the adsorption process will not interfere with the catalytic process. Yet, when the reaction temperature increases, the adsorption of β-MnO2 and γ-MnO2 increases as well. This strong adsorption would have a negative impact on the VAE catalytic activity because of the higher concentration of byproducts. The vibration absorption strength of layered-linked structural δ-MnO2 (Fig. 7d) and non-crystal AMO (Fig. 7e) catalysts demonstrates poor adsorption for VAE with the rise of reaction temperature, and this is directly connected to VAE catalytic activity. Meanwhile, the bands at 1735 and 1645 cm−1 might be related to the generation of aldehydic species [45]. These bands have been ascribed to a C═O stretching vibration mode. As the intensity of the in-situ spectra for OMS-2 was higher than that for δ-MnO2, this indicates that the cross-linked structural MnO2, including di- and mono-m-oxo-bridge-connected MnO6 structural motifs were more effective at activating VAE than the layered-linked structural δ-MnO2. Additionally, asymmetric and symmetric COO stretch intensities, v(COO), at 1557 and 1446 cm−1, respectively, correspond to the formation of acetate species from VAE oxidation [46]. When combined with the catalytic performance of VAE oxidation, these results were further evidence that the ester bond cleavage of VAE on the catalysts surface occurred first. With an increase in reaction temperature, the stretching vibrations corresponding to the formate species, v(HCOO), became more evident at 1382, 1342, and 1416 cm−1. These vibrations provide evidence of C—C cleavage of acetaldehyde and acetic acid intermediate over MnO2 catalysts. The formate species, which was a byproduct of acetaldehyde and acetic acid, was to further degrade into CO2 and H2O. The tautomerism between the enol structure and acetaldehyde throughout the reaction led to the identification of the 1025 cm−1 peaks as belonging to C═C—O stretching vibrations. The distinctive vibration peak of VAE has been mapped to the band between 1221 and 1145 cm−1. Additionally, the band intensities of acetate species and formate species at various catalysts were summarized, as shown in Fig. 7f. Detailed results showed that the lower band intensities of the formate and acetate adsorption species over cross-linked structural OMS-2 was observed than that of layered-linked structural δ-MnO2 and non-crystal AMO catalysts. It was explained that the reaction of the intermediate species (formate and acetic acid) with reactive oxygen species.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 7. In situ DRIFT spectra of vinyl acetate catalytic oxidation for (a) OMS-2, (b) γ-MnO2, (c) β-MnO2, (d) δ-MnO2, and (e) AMO catalyst at different reaction temperatures. (f) Summarized results of in situ DRIFT over MnO2 catalysts at 210 ℃. | |

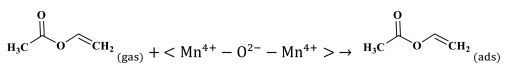

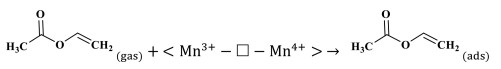

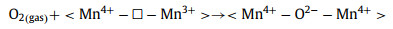

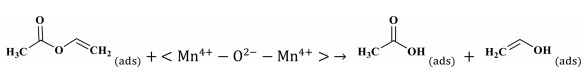

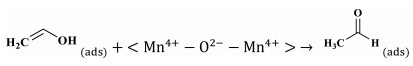

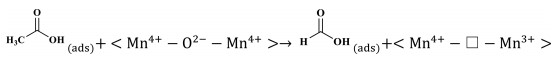

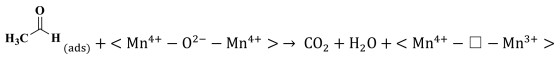

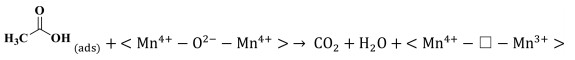

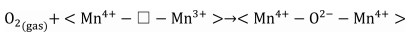

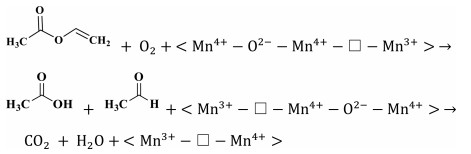

The reaction mechanism of catalytic oxidation of VAE pollutant over manganese dioxide was investigated, considering the differences between the various catalysts. The total oxidation of VAE over transition-metal oxides is governed by the Mars-van Krevelen redox mechanism. At the catalyst surface, molecules of ethyl acetate are adsorbed and converted into VAE(ads) on active metal sites (Mn4+-O2−-Mn4+ and/or Mn3+-Vo−Mn4+), which represent the corner- and edge-connected MnO6 structural motifs (Step 1, Eqs. 1 and 2). While, molecules of oxygen are adsorbed and activated into O(ads) on oxygen vacancies (Step 1ʹ, Eq. 3). While, the highly reducible bridging oxygen may react with VAE to create acetic acid and acetaldehyde owing to the rupture of the ester link (Step 2, Eq. 4). Nevertheless, the acetic acid would not be stable and it would degrade into formate species. In addition, the tautomerism that occurred between the enol structure and acetaldehyde was also a result of this reaction (Step 3, Eqs. 5 and 6). Adsorbed intermediate species (VAE, acetic acid, and acetaldehyde) and O(ads) are converted into carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O) at the end of the process (Step 4, Eqs. 7 and 8). Facilitating the activation of gas-phase oxygen on surface oxygen vacancies (Eqs. 9 and 10) [47] allowed for the replenishment of surface oxygen species by gas-phase oxygen. Based on the Mn–O distance, physicochemical characteristics, and porosities of MnO2, it was shown that a specific amount of formative oxygen vacancy and/or intrinsic vacancy in the Mn3+-Vo−Mn4+ may be relevant for VAE catalytic oxidation over MnO2 surface [48]. Cross-linked structural OMS-2 catalyst with both corner- and edge-connected MnO6 structural motifs led to more superior reducibility, unsaturated coordination Mn ions, defects sites, and oxygen species than that of the exclusive presence of edge-connected Mn ions in the layered structural δ-MnO2 and non-crystal AMO catalyst. The tunnel structure of OMS-2 caused higher catalytic activity and CO2 output than that of other structural MnO2. The OMS-2 showed that the more MnO6 edges and corners were exposed, the weaker the Mn—O bonds were because of the Jahn-Teller effect, and the more oxygen vacancies were generated from the instant active oxygen spilt over from the catalyst surface. These structural variations may facilitate the adsorption of oxygen molecules and the activation of VAE. To illustrate the catalytic oxidation of VAE in detail, consider the following depiction of the individual chemical steps involved. It should be noted that " □ " denotes oxygen deficiencies.

Step 1 VAE adsorption and activation:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

Step 1ʹ Oxygen molecule activation:

|

(3) |

Step 2 The breaking of the ester bond:

|

(4) |

Step 3 Tautomerism between enol structure and acetaldehyde:

|

(5) |

Acetic acid decomposes into formate species:

|

(6) |

Step 4 Adsorbed VOCs transformed into CO2 and H2O:

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

Step 1ʹʹ Re-activation of gas-phase oxygen:

|

(9) |

Overall reaction:

|

(10) |

However, the packaging and printing industries contribute to OVOC emissions by producing some of the most common types of OVOCs (primarily alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, and esters). The findings of an analysis of OMS-2′s catalytic activity in the oxidation of organic molecules are shown in Fig. S8 (Supporting information). These VOCs may be totally oxidized in a similar fashion to OMS-2 at lower temperatures. Because of the synergistic impact between the corner- and edge-connected MnO6 structural motifs of OMS-2 catalysts, this material has shown to be a powerful catalyst with promising application prospects for the reduction of VOC emissions.

In conclusion, the flammability, toxicity, and polymerizability of VAE pose a concern for the environment and human health. Nevertheless, no evidence of very efficient catalytic degradation of long-lasting vinyl acetate pollution has been revealed. The efficiency of VAE catalytic oxidation is assessed for various structural manganese oxides, including 2D layered-linked, 3D cross-linked, and amorphous structural manganese oxides with tuneable MnO6 structural motifs and accessible oxygen vacancies (VO-e and VO-c). In OMS-2 catalysts, the maximum catalytic activity was observed due to the synergistic effects of two kinds of oxygen vacancies and edging/corner-connected MnO6 structural motifs. Moreover, in situ experimental and theoretical methods are used to investigate the structure-activity relationship and the degradation process of VAE oxidation. Intriguingly, corner-connected MnO6 structural motifs and VO-c structural oxygen defect sites of manganese oxides significantly improved the low-temperature VAE activation, while edge-connected MnO6 structural motifs and VO-e oxygen vacancies of manganese oxides significantly improved the high CO2 yield. The availability of a redox couple, surface oxygen species, and weak Mn—O bonds are crucial to the activation of the C—H, C—O, and C═C bond and the deep catalytic oxidation of VAE, and both corner/edge-connected MnO6 and oxygen vacancies of manganese oxides were found to enhance the formation of these intermediate species. This work has the potential to provide an efficient structural and defect engineering technique for VOC oxidation catalysts.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22006079), the R&D Program of Beijing Municipal Education Commission (No. KJZD20191443001), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2016YFC0204203), the Project of Ningxia Key Research and Development Plan (No. 2020BEB04009), and National First-rate Discipline Construction Project of Ningxia (No. NXYLXK2017A04).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108437.

| [1] |

X. Xing, T. Zhao, J. Cheng, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 3065-3072. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.09.056 |

| [2] |

C. He, J. Cheng, X. Zhang, et al., Chem. Rev. 119 (2019) 4471-4568. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00408 |

| [3] |

P. Wu, S.Q. Zhao, X.J. Jin, et al., Appl. Surf. Sci. 574 (2022) 151707. DOI:10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.151707 |

| [4] |

Y.F. Jian, M.D. Ma, C.W. Chen, et al., Catal. Sci. Technol. 8 (2018) 3863-3875. DOI:10.1039/C8CY00444G |

| [5] |

Q.M. Ren, S.P. Mo, J. Fan, et al., Chin. J. Catal. 41 (2020) 1873-1883. DOI:10.1016/S1872-2067(20)63641-5 |

| [6] |

C. He, Z.Y. Jiang, M.D. Ma, et al., ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 4213-4229. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.7b04461 |

| [7] |

P.C. Guo, H.B. Qiu, C.W. Yang, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 402 (2021) 123846. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123846 |

| [8] |

C.Y. Ma, Z. Mu, J.J. Li, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (2010) 2608-2613. DOI:10.1021/ja906274t |

| [9] |

S.S. Chang, Y. Jia, Y.Q. Zeng, et al., J. Rare Earth 40 (2022) 1743-1750. DOI:10.1016/j.jre.2021.10.009 |

| [10] |

P. Wu, S.Q. Zhao, J.W. Yu, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12 (2020) 50566-50572. DOI:10.1021/acsami.0c17042 |

| [11] |

K.X. Cao, X. Dai, Z.B. Wu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 1206-1209. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.09.001 |

| [12] |

K. Shen, M.X. Jiang, X.W. Yang, et al., J. Rare Earth. 41 (2023) 523-530. DOI:10.1016/j.jre.2022.04.004 |

| [13] |

L. Li, L.P. Song, Z.Y. Fei, et al., J. Rare Earth. 40 (2022) 645-651. DOI:10.1016/j.jre.2021.02.004 |

| [14] |

Q.J. Yu, Y.C. Feng, J.H. Wei, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 3087-3090. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.09.072 |

| [15] |

X. Wang, Y. Liu, Y. Zhang, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 229 (2018) 52-62. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.02.007 |

| [16] |

Y. Gan, M.L. Fu, P. Liu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 2726-2730. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.09.006 |

| [17] |

L. Zhang, Y. Yang, Y.Z. Li, et al., Chin. J. Catal. 43 (2022) 379-390. DOI:10.1016/S1872-2067(21)63816-0 |

| [18] |

P.F. Smith, B.J. Deibert, S. Kaushik, et al., ACS Catal. 6 (2016) 2089-2099. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.6b00099 |

| [19] |

Y. Meng, K. Zhao, Z. Zhang, et al., Nano Res. 13 (2020) 709-718. DOI:10.1007/s12274-020-2680-5 |

| [20] |

M. Qi, Z. Li, Z. Zhang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107437. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.04.035 |

| [21] |

Y. Wang, K.S. Liu, J. Wu, et al., ACS Catal. 10 (2020) 10021-10031. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c02310 |

| [22] |

B. Chen, B. Wu, L.M. Yu, et al., ACS Catal. 10 (2020) 6176-6187. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c00459 |

| [23] |

F. Wang, H. Dai, J. Deng, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 46 (2012) 4034-4041. DOI:10.1021/es204038j |

| [24] |

W.N. Li, J. Yuan, S. Gomez, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (2005) 14184-14185. DOI:10.1021/ja053463j |

| [25] |

J. Jia, P.Y. Zhang, L. Chen, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 189 (2016) 210-218. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.02.055 |

| [26] |

L. Li, X. Feng, Y. Nie, et al., ACS Catal. 5 (2015) 4825-4832. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.5b00320 |

| [27] |

G. Zhu, J.G. Zhu, W.L. Li, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 52 (2018) 8684-8692. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.8b01594 |

| [28] |

W. Yang, Z.A. Su, Z. Xu, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 260 (2020) 118150. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118150 |

| [29] |

Y. Yang, J. Huang, S.W. Wang, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 142 (2013) 568-578. |

| [30] |

D.A. Kitchaev, H.W. Peng, Y. Liu, et al., Phys. Rev. B 93 (2016) 0451321-0451325. |

| [31] |

J.E. Penner-Hahn, Coord. Chem. Rev. 190-192 (1999) 1101-1123. DOI:10.1016/S0010-8545(99)00160-5 |

| [32] |

H. Dau, P. Liebisch, M. Haumann, et al., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 376 (2003) 562-583. DOI:10.1007/s00216-003-1982-2 |

| [33] |

A. Bergmann, I. Zaharieva, H. Daub, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 6 (2013) 2745-2755. DOI:10.1039/c3ee41194j |

| [34] |

S.P. Mo, S.D. Li, W.H. Li, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 4 (2016) 8113-8122. DOI:10.1039/C6TA02593E |

| [35] |

J.L. Wan, L. Zhou, H.P. Deng, et al., J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 407 (2015) 67-74. DOI:10.1016/j.molcata.2015.06.026 |

| [36] |

V. Santos, M. Pereira, J. Órfao, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 99 (2010) 353-363. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2010.07.007 |

| [37] |

L. Ye, P. Lu, D.S. Chen, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 2509-2512. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.12.040 |

| [38] |

T. Gao, M. Glerup, F. Krumeich, et al., J. Phys. Chem. C 112 (2008) 13134-13140. DOI:10.1021/jp804924f |

| [39] |

C. Julien, M. Massot, R. Baddour-Hadjean, et al., Solid State Ionics 159 (2003) 345-356. DOI:10.1016/S0167-2738(03)00035-3 |

| [40] |

J.T. Hou, Y.Z. Li, L.L. Liu, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 1 (2013) 6736-6741. DOI:10.1039/c3ta11566f |

| [41] |

G. Zhu, J. Zhu, W.J. Jiang, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 209 (2017) 729-737. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.02.068 |

| [42] |

S. Rong, P. Zhang, F. Liu, et al., ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 3435-3446. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.8b00456 |

| [43] |

Y. Zhou, H.P. Zhang, Y. Yan, J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. E 84 (2018) 162-172. DOI:10.1016/j.jtice.2018.01.016 |

| [44] |

G. Cheng, L. Yu, B. He, et al., Appl. Surf. Sci. 409 (2017) 223-231. DOI:10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.02.218 |

| [45] |

H. Sun, Z.G. Liu, S. Chen, X. Quan, Chem. Eng. J. 270 (2015) 58-65. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2015.02.017 |

| [46] |

T.H. Tan, J. Scott, Y.H. Ng, et al., ACS Catal. 6 (2016) 8021-8029. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.6b01833 |

| [47] |

N. Guillén-Hurtado, A. García-García, A. Bueno-López, et al., J. Catal. 299 (2013) 181-187. DOI:10.1016/j.jcat.2012.11.026 |

| [48] |

J.Z. Huang, S.F. Zhong, Y.F. Dai, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 52 (2018) 11309-11318. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.8b03383 |

2023, Vol. 34

2023, Vol. 34