b School of Science, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 210000, China;

c Shanghai Skin Disease Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200443, China

The incidence of malignant tumors is increasing worldwide, posing a threat to public health [1-3]. Numerous breakthroughs in tumor immunology and biotechnology have been reached recently using various strategies such as nanotechnology, gene therapy and combined formulations [4-8]. These advances have provided profound knowledge reserves and technical guidance for tumor immune research and development, allowing tumor immunotherapy to be widely recognized. Immune anti-cancer therapy has shown a fantastic medical breakthrough [9]. Immunotherapy has become the fourth most effective tumor treatment strategy, following surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy [10]. Several cancer immunotherapies exhibit encouraging potential against cancer. Cell therapy is an immune treatment approach applying culture technology in vitro to increase immune cells or using genetic modification to enhance the virulence of immune cells and then infusing them back into the human body to fight against diseases [11]. The therapy utilizes the patient's cells to attack tumor cells and enable the immune system to act like an "anti-cancer drug" [12], e.g., certain cell groups are isolated, genetically tailored, initiated and increased to the cell number required for treatment. Several immune cells, such as T cells, NK cells, dendritic cells and regulatory T cells (Tregs), can be redirected to outbreak tumors or boost local immune reply [13]. CAR-T cell therapy has shown promising potential for cancer treatment. CAR-T cell therapy involves transferring genetic material with specific antigen recognition domains and T cell activation signals into T cells through in vitro modification. The CAR-T enables T cells not to be limited to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) [14], but to independently recognize tumor antigens and directly associate with specific antigens on the surface of tumor cells [15], elevating the ability of the immune system to kill tumor cells. CAR-T cells are widely used in hematological cancer treatment, such as B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) [16], B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL), B-cell chronic lymphoblastic leukemia (B-CLL) [17] and multiple myeloma (MM) [18]. CAR-T cell therapy has been proven to have excellent results, eradicating very advanced leukemia and lymphoma and suppressing cancer cells long term. Meanwhile, CAR-T cells targeting CD19 and BCMA antigens have been clinically accepted worldwide. Cell therapy has gradually become one of the routine cancer treatments. Despite these advances, CAR-T cells still face certain significant challenges. CAR-T cells demonstrate compromised efficacy against solid tumors due to the complex interaction between various immune cell subsets, such as inhibition of the tumor microenvironment (TME), heterogeneity of tumor antigens or evasion mechanisms, and many other drug-resistant mechanisms [19]. Therefore, in the relevant indications of hematology and oncology, T cells are modified to regulate the immune response or kill the infected cells or cancer cells. For instance, CAR-T therapy is designed to improve the efficacy and reduce the toxicity associated with T cell therapy, while increasing patients' compliance to promote the production of CAR-T cells, making CAR-T cell therapy universally applicable and a potentially effective treatment method in cancer. In this review, we summarize the basic structure and evolution process of CAR-T cells. We pay more attention to the difficulties faced by CAR-T therapy and the current progress in designing more effective and CAR-T technology. In addition, we discuss the marketed products and the advance, while introducing the latest approach to break through and overcome the disadvantages of CAR-T cells. Finally, we provide perspectives and insights into CAR-T cell technology in the treatment of hematological malignant tumors and solid tumors.

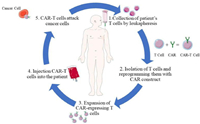

2. CAR-T cell structure and evolutionCAR is a chimeric antigen receptor that gives immune cells a new ability to target specific antigen proteins; T is the T cells that kill tumor cells. CAR-T is a tailored T cell having unique receptors termed CARs on their surface, obtained by delivering chimeric antigen receptor genes into the cells using various carriers such as liposomes and lipid nanoparticles[20,21]. Such CAR-T cells are expanded and finally infused back into the patient. This therapy releases a large number of effector factors through immunity. It will effectively kill tumor cells in a non-MHC-restricted way, treating malignant tumors (Fig. 1).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. The schematic illustration of preparing CAR-T cell therapy. | |

CAR consists of an extracellular binding domain, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular domain [22]. The critical CAR structure contains an artificial extracellular recognition domain (typically a single-stranded antibody that recognizes tumor-specific surface antigens) and an intracellular signal domain (Fig. 2).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Schematic diagram of the CAR structure. | |

The extracellular domain is the part of cell membrane proteins located outside the cytoplasm and exposed to the extracellular space. The extracellular domain consists of signal peptides, tumor-associated antigen recognition regions, and spacers. The role of signal peptides is to guide nascent proteins into the endoplasmic reticulum. Single-chain variable fragments (scFv) are fused from immunoglobulins' heavy and light chains through a flexible connector [23]. It would be used as a signal peptide in the outer domain of CAR, and its function is to recognize specific antigens directly without any MHC [10]. The antigen recognition region is usually a single-stranded antibody with many simple foreign recognition components. When it binds to the high affinity of the target, it could be used to identify any antigen.

The spacer region, also known as the hinge region, typically maintains the stability required for robust CAR expression and activity in effector cells [24] and is a necessary structure for connecting the antigen recognition region and transmembrane structure region [23]. The hinge region based on IgG is often used to build most CAR-T cells [23].

The transmembrane domain connects the extracellular antigen binding domain and the intracellular activation signal domain within the cell membrane. This region comprises homologous or heterologous dimer membrane proteins with an α spiral structure [25]. Frequently, the stability of the receptor is related to the transmembrane domain [23]. Changing the design of the transmembrane region will regulate the degree of expression of the CAR gene.

The intracellular domain is the functional end of the receptor and normally includes activation and co-stimulation signaling regions [26]. When an antigen recognition domain interacts with an antigen, an activation signal is transmitted to T cells, and the most common activation signal is CD3ζ. In addition, efficient T-cell activation requires co-stimulation signals [26]. These signals significantly drive the persistence and proliferation of antigen-stimulated T cells.

2.2. CAR-T structural developmentDepending on the structure of the intracellular region, CAR-T cells have been divided into four generations (Fig. 3). The first-generation CAR only provides signals through CD3ζ. Because no costimulatory molecules could transduce the value-added signals and induce cytokine production, the first generation of CAR-T cells cannot proliferate continuously, leading to a poor tumor-killing effect. A single CD3ζ signal cannot induce an effective T-cell response or produce enough cytokines [26].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. The evolution process of CAR structure. | |

The second generation of CAR adds costimulatory molecules or inducible costimulatory molecules in tandem with CD3ζ [27] based on the first generation. In addition to T cell receptor (TCR) and cytokine receptor antigen stimulation, T cell activation also requires costimulatory molecular signals [28], such as CD27, CD28, 4–1BB, OX40 [29]. The second-generation CAR provides two signals that meet the needs of T cell proliferation and activation, promote the synthesis of cytokines, complete the activation of T cells and avoid apoptosis. It is the most widely used CAR.

The third-generation CAR enhances the antitumor ability of CAR-T cells by combining multiple costimulatory domains, like CD28–41BB [30]. It could significantly prolong the antitumor activity, proliferation activity and survival cycle of T cells, as well as promote the secretion of cytokines, such as IL-2, TNF-α and IFN-γ.

The fourth-generation CAR inserts additional molecular elements into the CAR to express functional transgenic proteins, such as the interleukin gene or other cytokines [31]. The fourth-generation CAR aims to facilitate CAR-T cells to remodel the immune suppression in the TME by secreting anti-cancer cytokines [32]. This type of CAR can enhance the activation ability of T cells and attract and activate innate immune cells, thereby eliminating antigen-negative cancer cells. Besides, improving the expansion and persistence of CAR-T cells could make them resistant to the immunosuppressive tumor environment. These T cells are defined as CAR-T cells with immune-stimulating cytokines [31], also known as universal cytokine-mediated killing redirected T cells (TRUCKs) [23].

3. Strategies to overcome the drawbacks of CAR-T therapyCAR-T cell dysfunction is caused by several factors, including limited poor persistence, T-cell depletion, limited migration of T cells, TME, and antigen escape [33]. To improve the effectiveness and persistence of CAR-T cells and reduce the related toxic side effects, the researchers have proposed many improvement techniques.

3.1. Technologies to enhance the efficacyT-cell dysfunction is one cause that limits tumor treatment using CAR-T cells [34], manifested by loss of proliferative capacity and decreased release of cytokines. The T-cell effectiveness can be boosted by increasing cytokines release and the expression of chemokine receptors and downregulating inhibitory signals. As it is well known, cytokines are potent in modulating the immune system [3]. Promoting cytokine production is an effective strategy to enhance efficacy and is designed to improve the ability of CAR-T cells to actively modulate the cytokine environment in the TME. Tumor cells shape the TME by producing and secreting cytokines. These cytokines can inhibit T-cell function by recruiting immunosuppressive cells directly or indirectly [35]. Interleukin 15 (IL-15) belongs to the common family of γ-chain cytokines and plays a vital role in the survival and expansion of T cells [36]. Modifying CAR-T cells to produce IL-15 [37], IL-36γ [38], or/and IL-23 [39] through autocrine mechanisms could expand the persistence and antitumor ability of CAR-T cells [40]. Similarly, CAR-T cells combined with oncolytic adenoviruses expressing TNF-α and IL-2 also showed the effect of enhancing and prolonging T cell function [41].

The TME usually contains chemokines [42]. Tumor cells up-regulate or down-regulate chemokine or regulate chemokine expression in tumor-associated cells. Chemokine levels influence T-cell migration. The mismatches of chemokine receptors on CAR-T cells and abnormal expression of chemokines in tumors may lead to the decrease of T cells migration to tumor sites [34]. Thus, CAR-T cells were engineered to express chemokine receptors that match the chemokine of a specific tumor, targeting tumors and changing the defense mechanism of tumor cells. Studies have found that CAR-T cells expressing chemokine receptors (CXCR1 or CXCR2) exhibited an enhanced migration to tumor sites expressing IL-8 in the model of invasive tumor cells, such as glioblastoma, ovarian cancer and pancreatic cancer, inhibiting tumor growth and producing lasting immune memory [43]. Therefore, chemokine receptor-modified CAR could significantly heighten the migration and persistence of T cells in tumors.

A stable cell microenvironment is essential to ensure cells' normal metabolism and functional activities. In TME, many inhibitors may hinder the function of CAR-T cells [34]. At the same time, tumor cells could produce and enhance immunosuppression by adapting the TME, leading to tumor resistance and affecting the therapeutic effect [44]. For instance, inhibitory signaling pathways are intrinsic receptors that regulate extracellular and intracellular signals, including PD-1, CTLA-4, TIM-3 and LAG-3 [45]. They could physiologically inhibit T-cell function and increase the expression of inhibitory receptors in a depleted T-cell environment. Also, the expression level of the inhibitory receptor would be increased in the depleted T-cell environment [46]. Generally, immune checkpoint blockers are used to develop immunotherapy strategies to enhance the efficacy of T cells in tumors. PD-1/PD-L1 signaling in the tumor microenvironment is vital in limiting T cell activation, promoting cell depletion and cytokine production [47], thus contributing to tumor escape. Blocking the interaction of PD-1/PD-L1 is usually beneficial in restoring and maintaining the sustained lethality of T cells [45]. The antitumor activity of CAR-T cells and bystander tumor-specific T cells will be improved by making CAR-T cells produce anti-PD-1 single-stranded antibodies and acting in paracrine and autocrine ways [48]. As a negative regulator, TGF-β could reduce the proliferation and cytotoxicity of T cells in vivo [49]. TGF-β affects the differentiation and function of T cells by inducing Treg transformation. Knocking out endogenous TGF-β receptors in CAR-T cells has been proven to reduce the induced Treg transformation and prevent CAR-T cell failure [50]. Furthermore, modifying CAR-T cells to counter these inhibitory ligands and soluble factors [51] would effectively enhance the tumor clearance ability of CAR-T cells.

3.2. Strategies to reduce the toxicitySignificant toxicity is directly associated with inducing a strong immune-effector response in CAR-T cell therapy. The most common immune-mediated toxicity is cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome [52]. CRS is a systemic inflammatory response [53], and the factors that affect its incidence and severity are related to tumor load, lymphocyte failure and CAR-T cell dose [54].

Cytokines IL-6 and IL-1 play an essential role in the pathophysiology of CRS [52]. IL-6 is a pluripotent cytokine with pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects [55,56]. IL-6 is primarily produced by macrophages and other myeloid cells and acts in an autocrine manner, binding to other inflammatory signals to promote macrophage maturation and activation [57,58]. IL-1 is a multi-functional pluripotent cytokine produced primarily by monocytes and macrophages [59]. The use of IL-6 receptor antagonists (IL-6RA) has been found to prevent the development of overt CRS, but has not prevented neurotoxicity [60]. Treatment with IL-1 receptor antagonists (IL-1RA) controls CRS and prevents fatal neurotoxicity [60]. Activated CAR-T cells are able to produce a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). The release of this factor will lead to macrophage activation to produce IL-6 and IL-1 in vitro [61]. Therefore, blocking this pathway could eliminate the production of IL-6 and other cytokines by monocytes in vitro [62]. Studies have shown that a xenograft mouse model was established in CD19 CAR-T treatment, and the combined administration of the anti-GM-CSF antibody Lenzilumab enhanced the antitumor activity of CAR-T cells and reduced CRS and neuroinflammation [63].

The investigators found that treatment with Dasatinib not only stopped the cytolytic activity, cytokine production and proliferation of CAR-T cells in vivo and in vitro, but also partially or entirely inhibited the function of CAR-T cells. After the cessation of Dasatinib, the inhibitory effect is rapidly and completely reversed, and CAR-T cells regain their antitumor function [64]. This provides an opportunity for acute and transient control of CRS without terminating the action of CAR-T cells.

Second-generation genetically modified CAR-T cell products have been designed to efficiently destroy tumor cells. However, additional modifications also create safety and toxicity concerns while improving the capabilities of CAR-T cells against cancer. Using synthetic notch (SynNotch) receptors may solve related problems. This receptor contains an extracellular antigen recognition domain for specific targets. Its principle of action is that it leads to the release of intracellular transcription factors by connecting with the targets, then migrating to the nucleus to induce the expression of secondary CAR genes [65]. Because the SynNotch receptor is entirely independent of the T cell signaling mechanisms, the activation of T cells is not observed before CAR expression. Until SynNotch receptors are activated by antigens in the local TME [66], therapeutic T cells will remain completely inert (non-cytotoxic). CAR expression will only be induced when recognizing the second tumor-associated antigen. Consequently, SynNotch-CAR-T cells can be used as a universal platform to identify and reshape the local microenvironment associated with tumors, improve the selectivity of tumor cells, and reduce related toxic side effects.

Some CAR-T cells may cause off-target cytotoxicity by recognizing target cells expressed in normal tissues [67]. Therefore, another approach to improve safety is to enhance the ability of CAR to recognize tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and to strictly control the expression level of CAR in normal and diseased tissues. It has been found that T cells expressing CAR transiently can be designed by mRNA electroporation to effectively migrate to primary and metastatic tumor sites [68], or CRISPR/Cas9 technology can be used as well to integrate transgenes into limited genetic loci capable of controlling expression levels for precise sequence-specific intervention [69].

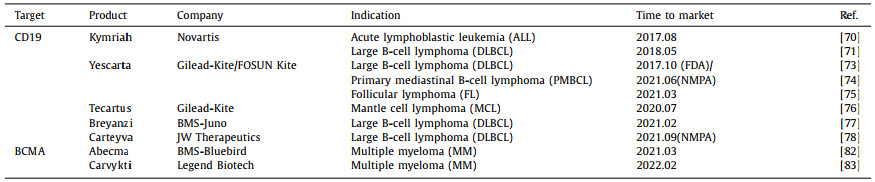

4. Approved CAR-T and clinical advancement 4.1. Marked productsThe Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved seven CAR-T cell therapy products for marketing to treat many types of hematologic malignancies (Table 1), including five CAR-T cell therapies targeting CD19 and two therapies targeting BCMA. Two products were approved by the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA), Axicabtagene Ciloleucel (Yescarta) produced by FOSUN Kite and Relmacabtagene Autoleucel (Carteyva) fabricated by JW Therapeutics.

|

|

Table 1 Global listed CAR-T cell therapy products. |

In August 2017, Kymriah, the world's first CAR-T cell therapy product, was approved for the treatment of recurrent/refractory (r/r) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [70] or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [71]. In an ELIANA trial (No. NCT02435849), the results showed that 81% of patients treated with Kymriah allowed overall remission within three months, with 60% of patients achieving complete remission(CR) 12 months after treatment [72], 47% of the patient experiencing grade 3 or more cytokine release syndrome, indicating safety and efficacy. In October of the same year, Yescarta became the second gene therapy approved by FDA. It is also the first CAR-T cell therapy product approved for treating adult patients with certain types of recurrent/refractory large B-cell lymphoma after receiving two or more systems. These types include unspecified diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [73], primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) [74] and follicular lymphoma (FL) [75]. A clinical trial ZUMA-1 (No. NCT02348216) displayed that 72% of patients attained objective response after receiving Yescarta treatment, and 51% reached CR [76]. The results proved the clinical significance of Yescarta. Subsequently, Tecartus and Breyanzi products for the treatment of adult recurrent/refractory mantle cell lymphoma (r/r MCL) [77] and recurrent/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (r/r DLBCL) [78] were launched between 2020 and 2021. Tecartus had already accomplished positive results in a clinical trial called ZUMA-2 (No. NCT02601313). The data showed that for adult patients with recurrent/refractory mantle cell lymphoma who had previously been treated with chemotherapy, anti-CD20 antibodies and Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors [79], the objective remission rate (ORR) was 92% at a median follow-up of 17.5 months. The complete remission rate (CRR) was 67% [80]. In addition, side-effect determination showed that 15% of patients developed grade three or more CRS, and 31% had grade three or above neurotoxicity [81]. Overall, Tecartus displayed a long-lasting response and good safety in treatment.

In March 2021, Abecma, the first CAR-T cell therapy product targeting BCMA, was approved for treating adult patients with recurrent/refractory multiple myeloma (r/r MM) after receiving four or more pre-treatment therapies [82]. This is a milestone breakthrough in CAR-T cell therapy and marks the official opening of the commercial production mode of BCMA-CAR-T. On February 28, 2022, the FDA officially approved another CAR-T therapy for BCMA, Carvykti. This product treats patients with recurrent/refractory multiple myeloma (r/r MM) [83], inducing early and lasting reactions and controllable side effects. Its clinical value of indications is superior to that of Abecma.

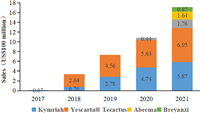

Currently, there are two products approved by NMPA in China. Yescarta injection is the first CAR-T cell therapy approved for marketing in China. FOSUN Kite conducted a technology transfer of Kite's Yescarta products in China in early 2017 and was authorized to localize production, opening a new future of tumor cell therapy in China and another important milestone in the company's global innovative R & D cooperation. The second approved autologous CAR-T product in China, Carteyva, is mainly aimed at recurrent/refractory large B-cell lymphoma (r/r DLBCL) in adult patients after second-line or above systemic treatment [84]. It is also the first CAR-T product in China to be approved as a Class 1 biological product. With the approval of CAR-T products on the market, sales of various products, mainly Yescarta, have increased year by year (Fig. 4). Increasing patients received CAR-T cell therapy. Yet, researchers still need to investigate the progression of CAR-T cells in these patients on a larger scale in the years and decades after treatment to draw more appropriate conclusions. Overall, CAR-T cell therapy has gained increasing attention, and the competition will intensify.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Global sales of listed CAR-T products from 2017 to 2021 (US$100 million). | |

CAR-T cell immunotherapy is currently being studied in several hematological and solid tumor types. The use of CAR-T cells as a cancer treatment has been widely studied in patients with B-cell malignancies, and outstanding achievements have been made in treating acute lymphoblastic leukemia, lymphoma and other blood tumors. Nowadays, a primary CAR-T concern is how to efficiently and effectively expand CAR-T cell production.

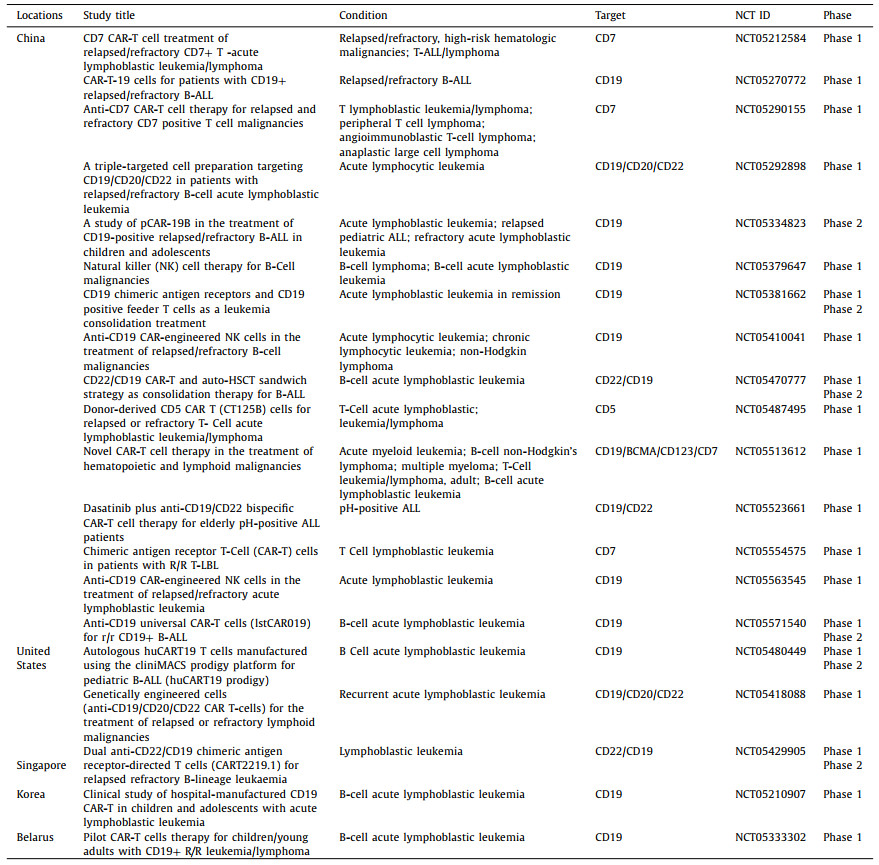

Many CAR-T cell therapies are currently being evaluated worldwide. We use the keyword CAR or chimeric antigen receptor to search from the clinical trial website of Clinicaltrials.gov. According to the website, more than 800 clinical trials of CAR-T cells for cancer are currently underway worldwide. Among them, 371 clinical trials have been directed in China, 258 trials are being managed in the United States and 68 studies have been conducted in Europe [85]. Because of the large number of clinical trials involved, we take acute lymphoblastic leukemia as a typical case and list the latest recruiting CAR-T clinical trials registered worldwide in 2022 (Table 2).

|

|

Table 2 Globally registered CAR-T clinical trials in 2022. |

In March 2022, FOSUN Kite announced that its second CAR-T cell therapy product, FKC889, got approval from NMPA to conduct clinical trials and was expected to be marketed shortly. FKC889 is the second CAR-T cell therapy in the field of hematological oncology localized by FOSUN Kite through technology transfer, according to Kite's Tecartus. It targets adult recurrent/refractory mantle cell lymphoma (r/r MCL). At the same time, the company also performed clinical trials on other CAR-T products with potential targets, such as CD4, CD20, CD19/CD20, etc. Multi-target CAR-T cell therapy is expected to be applied further in the future.

Arcellx in the United States planned to advance the development of CAR-T cell therapy CART-ddBCMA in 2022. The product is the first candidate based on the ddCAR platform and is undergoing a Phase Ⅰ clinical study to treat recurrent/refractory multiple myeloma (r/r MM) [86]. The candidate therapy has received fast-track qualification, advanced regenerative medicine therapy certification and orphan drug qualification granted by FDA [87]. Currently, most existing cell therapy schemes use the biology-based single-strand variable fragment (scFv) binding domain. It is often beneficial to a limited number of patients, frequently leads to high toxicity, and has narrow applicability in treatable indications [88]. Arcellx overcomes these limitations by designing a new class of D-Domain-driven autologous and allogeneic CAR-T cells, including classic single-infusion CAR-T (called ddCAR) and dose-controllable universal CAR-T (called ARC-SparX). D-Domain is a small, stable, fully synthetic bond with hydrophobic nuclei [86]. Its unique structure may enable higher transduction efficiency, higher cell surface expression, and lower rigid signaling when used in CAR-T cells. ddCAR consists of an intracellular T-cell signaling domain similar to conventional CAR with D-Domain and acts as an extracellular antigen-binding region [89]. This design improved the targeting ability and enhanced the binding affinity by using a new synthetic binding skeleton D-Domain to replace the scFv in CAR-T as the antigen binding domain.

5. CAR-T cell development 5.1. CAR-T cells targetsThe accumulated clinical data have confirmed that CAR-T therapy has significantly affected the treatment of hematological tumors. CAR-T therapy has a mature CAR structure, preparation and clinical scheme. During the research of other indications in hematology and oncology, further efforts will be made to study and verify CAR-T cells' new targets and find the best antigen combination and treatment plan. Selecting and utilizing the target is the key to determining CAR-T therapy's potential.

CAR-T cells targeting CD19 antigen in B-cell leukemia [90] and lymphoma [91] have achieved a better antitumor effect with good coverage and specificity. For the treatment of solid tumors, it is difficult to obtain an ideal target like CD19. Therefore, the role of CAR-T therapy should not be limited to killing cancer cells directly, but can kill cancer cells indirectly by activating endogenous tumor immune response and destroying the tumor growth environment. The identification of suitable surface antigens in solid tumors is more complicated. Here, we focus on CAR-T cell targets explored in solid tumor clinical trials using colorectal cancer (CRC) as an example.

CRC is the second most fatal cancer and the third most prevalent malignant tumor globally [92]. Various pathways mediating the initiation, multiplication, and migration of CRC, such as EGF/EGFR, VEGF/VEGFR and TGF-β/SMAD [93], contain ideal targets for CAR-T therapy. Epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), a tyrosine kinase receptor family member, is highly expressed in many cancer cells [94]. Its overexpression is associated with an increased risk of cancer recurrence and poor prognosis. In preclinical studies, relevant trials have developed anti-HER2 CAR-T cells and validated their efficiency against HER2-positive cancers (NCT02713984). In the phase Ⅰ clinical trial, investigators combined HER2-specific CAR-T cells with oncolytic adenovirus (CAdVEC) to treat CRC (NC03740256). CAdVEC can transmit multiple transgenes in vivo, stimulate different immune axes, and produce additive antitumor effects [95]. CAdVEC responds to tumors by creating a pro-inflammatory microenvironment after receiving HER2-specific CAR-T cells [96]. Studies have also shown that CAdVEC activates endogenous NK-cell antitumor activity in a humanized mouse model [97]. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) regulates cell proliferation, survival and differentiation [98]. Inhibition of EGFR is a primary therapeutic goal in cancer treatment. Phases Ⅰ and Ⅱ clinical trials have evaluated the safety and feasibility of EGFR and EGFR IL-12 CAR-T cells for treating CRC (NCT03542799, NCT02959151). Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is a common biomarker in gastrointestinal cancer tumors [99], and it is widely expressed in colorectal cancer tissues and serum [100]. A preclinical study has proved that anti-CEA CAR-T cells can effectively kill CEA target cells (NCT02349724). The study also proved that CEA-CAR-T cell therapy is well tolerated and safe in CEA-positive CRC patients [100]. The selection criteria of targets are not unique. CAR-T products for other targets are also under active research and development, such as CD133 CAR-T cells [101], tumor-associated glycoprotein 72 (TAG-72) CAR-T cells [102], Mucin-1 (MUC1) CAR-T cells [103], epithelial cell adhesion molecules (EpCAM) CAR-T cells [104], etc.

Target selection is a fundamental and crucial determinant of CAR-T therapy efficacy and always aims to find target cells that are homogeneously and stably expressed in cancer cells. Strategies to optimize the function of CAR-T cells in solid tumors, including identifying more vital and more potential targets to help eradicate tumors, remain one of the key goals in the current development of CAR-T cells.

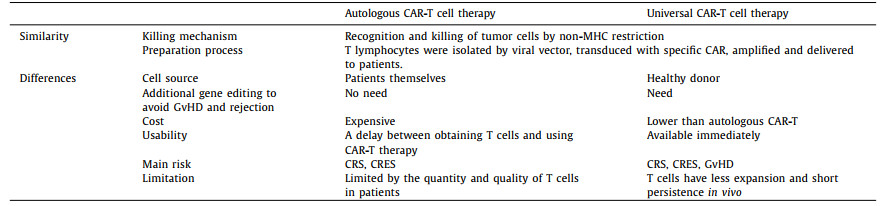

5.2. Universal CAR-T cell therapyCAR-T products that have been marketed worldwide are autologous therapies. Each cancer patient's T cells need to be improved during preparation and re-injected into the patient after expansion. However, some patients have compromised immune systems due to pre-treatment, and their T cells may not be available for CAR-T preparation. Meanwhile, CAR-T products of autologous therapy have shortcomings, such as higher production costs and longer preparation cycles. Therefore, many research institutions and pharmaceutical companies at home and abroad have promoted the development of allogeneic or universal CAR-T (UCAR-T) therapies. UCAR-T contains two broad categories, universal CAR design and universal T cells. The former is based on a specially designed CAR, so CAR-T cells can target a variety of tumor antigens without further genetic modification. And the latter uses CRISPR gene editing and other means to edit the genes of allogenic CAR-T cells [105], killing specific tumor cells while eliminating immune rejection. The most prominent feature of UCAR-T cells is that T cells are not derived from the patient itself but are extracted from healthy donor populations. Thus, the activity of these T cells is more uniform, and it is also convenient for the early production of CAR-T products for the timely treatment of different patients. Despite sharing the exact killing mechanism, UCAR-T cells have different manufacturing processes, costs, safety, and suitability (Table 3).

|

|

Table 3 Comparison of autologous and universal CAR-T cell therapies. |

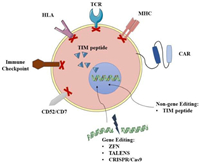

Enhancing the function of universal CAR-T cells based on gene editing is a type of UCAR-T cell therapy that has been widely studied, and some related products have already entered clinical research. Allogeneic CAR-T cells can be edited by gene editing techniques such as zinc-finger nucleases (ZFN) [106], transcription activator-like nucleases (TALENS) [107] and CRISPR/Cas9 [108] (Fig. 5). After knocking out T cell receptor (TCR) and human leukocyte antigen (HLA), immune rejection and Graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) [105] will be significantly weakened. For example, UCART19, developed by Allogene, uses gene editing to knock out genes that express the CD52 protein, making cells resistant to Alemtuzumab. At the same time, CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing used to generate universal CAR-T has begun to combine with other transgenic techniques to allow effective DNA modification of human T cells. This technology will further promote the development of currently available gene manipulation strategies and is expected to produce a powerful antitumor effect. On the other hand, the FDA approved Celyad's CYAD-101 investigational new drug (IND) application in July 2018. This is the world's first non-gene editing UCAR-T clinical project, marking the entry of generic CAR-T cells that are not based on gene editing into the market competition queue. This product reduces GvHD by expressing the TCR inhibitory molecule (TIM peptide), tampering with or eliminating the TCR signals (Fig. 5) [105].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Gene and non-gene editing of universal CAR-T cell. | |

UCAR-T cell therapy has apparent advantages over standard CAR-T cell therapy but also has higher safety and specificity requirements. Long-term observation is still needed for the persistence and evaluation of the side effects of the treatment. As more and more companies and researchers invest in it, this field will usher in subsequent developments.

5.3. Other CAR cellsAlthough CAR-T cell immunotherapy is developing rapidly, clinical applications still have shortcomings. The interaction between the TME and immune cells would affect the clinical results of immunotherapy [109]. For instance, it shows low efficacy in treating solid tumors and related side effects in immunotherapy. Immune cell infiltration and excessive cytokines production could lead to a heterogeneous inflammatory TME [109], promoting the growth and metastasis of tumor cells in an inflammatory environment. Immune cells have various functions and complex components. The functions and components of immune cells are diverse and complex [110]. Usually, the central immune cells involved in killing tumors include T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, NK cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells. They may overcome the defects of CAR-T cells and show significant antitumor efficacy.

Scientists pay increasing attention to NK-cell tumor immunotherapy. NK cells are antitumor effector cells. They account for 15 percent of all circulating lymphocytes and have functions not limited by MHC, cytotoxicity, cytokine generation, and immune memory [111]. Studies have found that mature NK cells can quickly recognize differences between autologous and allogeneic cells [112]. In contrast to T lymphocytes, NK cells do not induce GvHD and, in most cases, play a regulatory role [113]. Besides, the types of cytokines produced by NK cells differ from those produced by T lymphocytes. Active NK cells usually secrete IFN-γ to further inhibit the growth of cancer cells [114], while CAR-T cells generally release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6 [115], resulting in adverse reactions of cytokine release syndrome. With the development of gene modification techniques, NK cells can be further edited, including the introduction of CARs and knockout inhibition genes, while maintaining high cell viability and negligible off-target effects [116]. Since NK cells can recognize and kill tumor cells, increasing the penetration of NK cells into tumors will be a possible strategy to enhance the antitumor activity.

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are a small subset of immune cells specifically designed to suppress excessive immune activation and maintain immune homeostasis in vivo [117]. Generally, Treg cells also play an immunomodulatory role in many inflammatory and autoimmune diseases by modulating anti-inflammatory cytokines secretion [28].

With the continuous improvement of Treg manufacturing technology and widespread applications of synthetic biology and gene editing technology, CAR-Treg cell therapy will play an increasingly important role. CAR-Treg cells are primarily used directly for GvHD and organ transplant rejection [118]. Unlike most autoimmune diseases, there is an obvious target in transplantation: the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecule [119]. These CARs-expressing T cells bypass HLA restrictions when activated and increase specificity through co-receptor signals [120], as well as the targeting flexibility of CARs. In other words, CAR-Treg cells could recognize cell surface molecules without the help of HLA expression [121] and avoid immune escape.

The unique advantages of CAR-NK and CAR-Treg cells show great potential and broad prospects in tumor immunotherapy and are very likely to bring breakthroughs to tumor treatment under CAR modification.

6. Conclusions and perspectivesCAR-T cell therapy has rapidly moved from the initial stage to the rapid development stage. In August 2017, Novartis' Kymriah was approved for marketing in the US as the world's first CAR-T drug, thus kicking off the global era of CAR-T therapy. Increasing preclinical and clinical trial results have revealed new efficacy, drug resistance mechanisms and so on. Scientists have further promoted the screening for new targets, elucidated new signaling mechanisms and applied new cellular techniques. Several techniques have been established to enhance the efficacy of CAR T cells. By modifying CAR-T cells, they could self-regulate the production of cytokines, express chemokine receptors and reduce the expression level of inhibitory receptors [122,123]. Regarding safety, for cytokine release syndrome, it is proposed to use combined drugs to reduce neurotoxicity or to use SynNotch-CAR-T cells to improve the selectivity of tumor cells. In addition, scientists have designed universal CAR-T cells, CAR-NK cells, CAR-Treg cells and other novel CAR-T cells by applying gene editing technologies [124,125]. Different types of CAR-T cells provide multiple options for tumor cellular immunotherapy.

When naturally occurring T cells are ineffective in controlling disease, improved T cells may be a better choice. Compared with traditional tumor treatment methods, cellular immunotherapy has six advantages [126]: safety, individualization, persistence, thoroughness, universality, and little drug resistance. Unlike traditional chemical and biological drugs, CAR-T therapy is to re-inject chimeric receptor T cells genetically modified to express specific antigens into the patient to produce immunity. It belongs to the category of cell therapy. CAR-T cell immunotherapy combines T cells' dynamics with antibodies' antigen specificity as a breakthrough treatment. Since T-cell recognition of antigens does not depend on the MHC, the limitations of the T-cell receptor (TCR)-induced immunity could be mitigated and immune escape could be targeted to overcome [127]. Immunotherapy has become a hot topic in tumor research, and the immune mechanism centered on T cells has gradually been revealed. While conducting an in-depth study on how cancer cells behave, we must insist on combining standard and innovative treatments. New approaches will open and improve inherent cognition, break through the limitations of the original method and promote the development of new technologies.

On the other hand, cell therapy has highly specialized requirements from research to production. The high production cost, lengthy process and the inability to form a standardized process have contributed to the high price of cellular immunotherapy, making it universally applicable to most patients. Meanwhile, problems in tumor cells, such as cytokine release syndrome, nervous system toxicity, TME challenges and other issues, remain to be solved, impairing the use of CAR-T products to a certain extent. Therefore, we need to continuously improve CAR-T technology, develop effective targeted therapy, and reduce toxicity without affecting antitumor activity so that CAR-T cell therapy can be used for different tumor entities and more patients.

Thus far, although there is still a gap between the popularity of cell therapy and traditional methods, it has gradually shown the trend of catching up. Cell gene therapy has become one of the cutting-edge pharmaceutical fields with tremendous development potential. As CAR-T cell therapy continues to obtain breakthroughs, we will consciously and creatively utilize the immune system to fight against cancer and other diseases. Compared with other immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors and cytokine therapy [128], CAR-T cell therapy has elevated target ability and could target multiple pathways. Notably, CAR-T cell therapy demonstrates practical efficacy against several poor prognoses and rare tumors. Moreover, CAR-T can target carbohydrates and lipids besides protein receptors and polypeptide antigens, indicating its potential to combat other diseases, such as inflammation and infection. CAR-T therapy has become a hot spot in the field of tumor immunotherapy. Many enterprises at home and abroad compete for the layout, and the market scale will be expanded step by step. It is necessary not only to strengthen technological innovation and continue to deepen technological study and development but also to combine the technologies of companies in various countries to jointly promote industrial development. CAR-T products are expected to grow rapidly in the near future, occupying a large part of the global market share. It is believed that CAR-T technology, as an emerging treatment method, will benefit more patients under the updated iteration of technology and the support of national policies because of its unique efficacy and advantage.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81872823, 82073782 and 82241002), the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (No. 19430741500), National Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for Undergraduate (No. 202210316145), and the Key Laboratory of Modern Chinese Medicine Preparation of Ministry of Education of Jiangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. zdsys-202103).

| [1] |

W. Yang, C. Lei, S. Song, et al., Cancer Cell Int. 21 (2021) 1-14. DOI:10.1186/s12935-020-01646-5 |

| [2] |

E.I. Hwang, E.J. Sayour, C.T. Flores, et al., Nat. Cancer 3 (2022) 11-24. DOI:10.1038/s43018-021-00319-0 |

| [3] |

Q. Xiao, X. Li, Y. Li, et al., Acta Pharm. Sin. B 11 (2021) 941-960. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2020.12.018 |

| [4] |

E. Khatoon, D. Parama, A. Kumar, et al., Life Sci. 306 (2022) 120827. DOI:10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120827 |

| [5] |

M. Yuan, Y. Zhao, H.T. Arkenau, et al., Signal. Transduct. Tar. 7 (2022) 1-18. DOI:10.1038/s41392-021-00710-4 |

| [6] |

Q. Xiao, X. Li, C. Liu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 4191-4196. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.01.083 |

| [7] |

M. Zoulikha, W. He, Pharm. Res. 39 (2022) 441-461. DOI:10.1007/s11095-022-03214-0 |

| [8] |

G.F. Boafo, Y. Shi, Q. Xiao, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 4600-4604. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.04.033 |

| [9] |

O. Demaria, S. Cornen, M. Daëron, et al., Nature 574 (2019) 45-56. DOI:10.1038/s41586-019-1593-5 |

| [10] |

M.M.E. Ahmed, J. Sci. Res. Med. Biol. 2 (2021) 86-116. |

| [11] |

Y. Song, Y. Huang, F. Zhou, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 597-612. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.08.090 |

| [12] |

S. Rafiq, C.S. Hackett, R.J. Brentjens, Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17 (2020) 147-167. DOI:10.1038/s41571-019-0297-y |

| [13] |

N.N. Shah, T.J. Fry, Nature Rev. Clin. Oncol. 16 (2019) 372-385. |

| [14] |

J. Masoumi, A. Jafarzadeh, J. Abdolalizadeh, et al., Acta Pharm. Sin. B 11 (2021) 1721-1739. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2020.12.015 |

| [15] |

A.D. Fesnak, C.H. June, B.L. Levine, Nat. Revi. Cancer 16 (2016) 566-581. DOI:10.1038/nrc.2016.97 |

| [16] |

F.L. Locke, S.S. Neelapu, N.L. Bartlett, et al., Mol. Ther. 25 (2017) 285-295. DOI:10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.10.020 |

| [17] |

C.J. Turtle, K.A. Hay, L.A. Hanafi, et al., J. Clin. Oncol. 35 (2017) 3010-3020. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2017.72.8519 |

| [18] |

S.A. Ali, V. Shi, I. Maric, et al., Blood 128 (2016) 1688-1700. |

| [19] |

L. Fu, X. Ma, Y. Liu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 1718-1728. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.10.074 |

| [20] |

Y. He, W. Zhang, Q. Xiao, et al., Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 17 (2022) 817-837. DOI:10.1016/j.ajps.2022.11.002 |

| [21] |

K.T. Magar, G.F. Boafo, X. Li, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2021) 587-596. |

| [22] |

R. Huang, X. Li, Y. He, et al., J. Hematol. Oncol. 13 (2020) 86. DOI:10.1186/s13045-020-00910-5 |

| [23] |

C. Zhang, J. Liu, J.F. Zhong, et al., Biomark Res. 5 (2017) 22. DOI:10.1186/s40364-017-0102-y |

| [24] |

Y. Zhao, X. Zhou, Immunotherapy 12 (2020) 653-664. DOI:10.2217/imt-2019-0139 |

| [25] |

S.K. Tasian, R.A. Gardner, Ther. Adv. Hematol. 6 (2015) 228-241. DOI:10.1177/2040620715588916 |

| [26] |

A.Z. Mehrabadi, R. Ranjbar, M. Farzanehpour, et al., Biomed. Pharmacother. 146 (2021) 112512. |

| [27] |

M. Bell, S. Gottschalk, Front. Immunol. 12 (2021) 684642. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2021.684642 |

| [28] |

Y. Fu, Q. Lin, Z. Zhang, et al., Acta Pharm. Sin. B 10 (2020) 414-433. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2019.08.010 |

| [29] |

M.F. Sanmamed, F. Pastor, A. Rodriguez, et al., Semin. Oncol. 42 (2015) 640-655. DOI:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.05.014 |

| [30] |

B.G. Till, M.C. Jensen, J. Wang, et al., Blood 119 (2012) 3940-3950. DOI:10.1182/blood-2011-10-387969 |

| [31] |

M. Chmielewski, H. Abken, Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 15 (2015) 1145-1154. DOI:10.1517/14712598.2015.1046430 |

| [32] |

H. Dana, G.M. Chalbatani, S.A. Jalali, et al., Acta Pharm. Sin. B 11 (2021) 1129-1147. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2020.10.020 |

| [33] |

C.L. Bonifant, H.J. Jackson, R.J. Brentjens, et al., Mol. Ther-Oncolytics. 3 (2016) 16011. DOI:10.1038/mto.2016.11 |

| [34] |

F. Freitag, M. Maucher, Z. Riester, et al., Curr. Opin. Oncol. 32 (2020) 510-517. DOI:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000653 |

| [35] |

M.A. Morgan, A. Schambach, Front. Immunol. 9 (2018) 2493. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02493 |

| [36] |

A.M. Esteves, E. Papaevangelou, D. Smolarek, et al., Front. Mol. Biosci. 8 (2021) 755764. DOI:10.3389/fmolb.2021.755764 |

| [37] |

Y. Chen, C. Sun, E. Landoni, et al., Clin. Cancer Res. 25 (2019) 2915-2924. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1811 |

| [38] |

X. Li, A.F. Daniyan, A.V. Lopez, et al., Leukemia 35 (2021) 506-521. DOI:10.1038/s41375-020-0874-1 |

| [39] |

X. Ma, P. Shou, C. Smith, et al., Nat. Biotechnol. 38 (2020) 448-459. DOI:10.1038/s41587-019-0398-2 |

| [40] |

G. Krenciute, B.L. Prinzing, Z. Yi, et al., Cancer Immunol. Res. 5 (2017) 571-581. DOI:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0376 |

| [41] |

K. Watanabe, Y. Luo, T. Da, et al., JCI Insight 3 (2018) 99573. DOI:10.1172/jci.insight.99573 |

| [42] |

C. Querfeld, S. Leung, P.L. Myskowski, et al., Cancer Immunol. Res. 6 (2018) 900-909. DOI:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0270 |

| [43] |

L. Jin, H. Tao, A. Karachi, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 4016. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-11869-4 |

| [44] |

M.D. Wellenstein, K.E. de Visser, Immunity 48 (2018) 399-416. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.004 |

| [45] |

Q. Xie, J. Ding, Y. Chen, Acta Pharm. Sin. B 11 (2021) 1365-1378. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.027 |

| [46] |

E.J. Wherry, M. Kurachi, Ther. Adv. Hematol. 15 (2015) 486-499. |

| [47] |

D.S. Thommen, V.H. Koelzer, P. Herzig, et al., Nat. Med. 24 (2018) 994-1004. DOI:10.1038/s41591-018-0057-z |

| [48] |

S. Rafiq, O.O. Yeku, H.J. Jackson, et al., Nat. Biotechnol. 36 (2018) 847-856. DOI:10.1038/nbt.4195 |

| [49] |

L. Yang, Y. Pang, H.L. Moses, Trends Immunol. 31 (2010) 220-227. DOI:10.1016/j.it.2010.04.002 |

| [50] |

N. Tang, C. Cheng, X. Zhang, et al., JCI Insight 5 (2020) e133977. DOI:10.1172/jci.insight.133977 |

| [51] |

C.C. Kloss, J. Lee, A. Zhang, et al., Mol. Ther. 26 (2018) 1855-1866. DOI:10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.05.003 |

| [52] |

E.C. Morris, S.S. Neelapu, T. Giavridis, et al., Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22 (2021) 85-96. |

| [53] |

D.W. Lee, B.D. Santomasso, F.L. Locke, et al., Biol. Blood Marrow Tr. 25 (2019) 625-638. DOI:10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.12.758 |

| [54] |

K.A. Hay, L.A. Hanafi, D. Li, et al., Blood 130 (2017) 2295-2306. DOI:10.1182/blood-2017-06-793141 |

| [55] |

W. He, N. Kapate, C.W. Shields IV, et al., Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 165 (2020) 15-40. |

| [56] |

K.T. Magar, G.F. Boafo, M. Zoulikha, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107453. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.04.051 |

| [57] |

C.A. Hunter, S.A. Jones, Nat. Immunol. 16 (2015) 448-457. DOI:10.1038/ni.3153 |

| [58] |

M. Zoulikha, F. Huang, Z. Wu, et al., J. Control. Rel. 346 (2022) 260-274. DOI:10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.04.027 |

| [59] |

P. Migliorini, P. Italiani, F. Pratesi, et al., Autoimmun. Rev. 19 (2020) 102617. DOI:10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102617 |

| [60] |

M. Norelli, B. Camisa, G. Barbiera, et al., Nat. Med. 24 (2018) 739-748. DOI:10.1038/s41591-018-0036-4 |

| [61] |

Y. Liu, Y. Fang, X. Chen, et al., Sci. Immunol. 5 (2020) eaax7969. DOI:10.1126/sciimmunol.aax7969 |

| [62] |

M. Sachdeva, P. Duchateau, S. Depil, et al., J. Biol. Chem. 294 (2019) 5430-5437. DOI:10.1074/jbc.AC119.007558 |

| [63] |

R.M. Sterner, R. Sakemura, M.J. Cox, et al., Blood 133 (2019) 697-709. DOI:10.1182/blood-2018-10-881722 |

| [64] |

K. Mestermann, T. Giavridis, J. Weber, et al., Sci. Transl. Med. 11 (2019) eaau5907. DOI:10.1126/scitranslmed.aau5907 |

| [65] |

K.T. Roybal, J.Z. Williams, L. Morsut, et al., Cell 167 (2016) 419-432. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.011 |

| [66] |

K.T. Roybal, W.A. Lim, Annu. Rev. Immunol. 35 (2017) 229-253. DOI:10.1146/annurev-immunol-051116-052302 |

| [67] |

C.H. Lamers, S. Sleijfer, S. van Steenbergen, et al., Mol. Ther. 21 (2013) 904-912. DOI:10.1038/mt.2013.17 |

| [68] |

G.L. Beatty, A.R. Haas, M.V. Maus, et al., Cancer Immunol. Res. 2 (2014) 112-120. DOI:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0170 |

| [69] |

J. Eyquem, J. Mansilla-Soto, T. Giavridis, et al., Nature 543 (2017) 113-117. DOI:10.1038/nature21405 |

| [70] |

S.L. Maude, T.W. Laetsch, J. Buechner, et al., N. Engl. J. Med. 378 (2018) 439-448. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1709866 |

| [71] |

S.J. Schuster, M.R. Bishop, C.S. Tam, et al., N. Engl. J. Med. 380 (2019) 45-56. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1804980 |

| [72] |

E. Harris, J.J. Elmer, Biotechnol. Progr. 37 (2021) e3066. DOI:10.1002/btpr.3066 |

| [73] |

S.S. Neelapu, F.L. Locke, N.L. Bartlett, et al., N. Engl. J. Med. 377 (2017) 2531-2544. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1707447 |

| [74] |

I. Papadouli, J. Mueller-Berghaus, C. Beuneu, et al., Oncologist 25 (2020) 894-902. DOI:10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0646 |

| [75] |

I. Papadouli, J. Mueller-Berghaus, C. Beuneu, et al., Oncologist 25 (2020) 1-9. DOI:10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0883 |

| [76] |

N. Bouchkouj, Y.L. Kasamon, R.A. de Claro, et al., Clin. Cancer Res. 25 (2019) 1702-1708. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2743 |

| [77] |

Nat. Biotechnol. 38 (2020) 1012-1012.

|

| [78] |

D.S. Aschenbrenner, Am. J. Nurs. 121 (2021) 21-22. DOI:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000767784.40244.e4 |

| [79] |

A. Mian, B.T. Hill, Expert Opin. Biol. Th. 21 (2021) 435-441. DOI:10.1080/14712598.2021.1889510 |

| [80] |

M.L. Wang, K.A. Blum, P. Martin, et al., Blood 126 (2015) 739-745. |

| [81] |

M. Wang, J. Munoz, A. Goy, et al., N. Engl. J. Med. 382 (2020) 1331-1342. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1914347 |

| [82] |

A. Robinson, Oncology 43 (2021) 21. |

| [83] |

A. McClanahan, M. Spychalla, J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 13 (2022) 328. DOI:10.6004/jadpro.2022.13.3.30 |

| [84] |

Z. Ying, H. Yang, Y. Guo, et al., Cancer Med. 10 (2021) 999-1011. DOI:10.1002/cam4.3686 |

| [85] |

J. Wei, Y. Guo, Y. Wang, et al., Cell. Mol. Immunol. 18 (2021) 792-804. DOI:10.1038/s41423-020-00555-x |

| [86] |

J.M. Buonato, J.P. Edwards, L. Zaritskaya, et al., Mol. Cancer Ther. 21 (2022) 1171-1183. DOI:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0552 |

| [87] |

D. Ilic, M. Liovic, Regen. Med. 15 (2020) 1833-1840. DOI:10.2217/rme-2020-0052 |

| [88] |

M.J. Frigault, M.R. Bishop, E.K. O'Donnell, et al., Blood 136 (2020) 2. |

| [89] |

H. Qin, J.P. Edwards, L. Zaritskaya, et al., Mol. Ther. 27 (2019) 1262-1274. DOI:10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.04.010 |

| [90] |

T. Zhang, L. Cao, J. Xie, et al., Oncotarget 6 (2015) 33961-33971. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.5582 |

| [91] |

J.N. Kochenderfer, M.E. Dudley, S.H. Kassim, et al., J. Clin. Oncol. 33 (2015) 540-549. |

| [92] |

Y.H. Xie, Y.X. Chen, J.Y. Fang, Signal Transduct. Tar. 5 (2020) 22. DOI:10.1038/s41392-020-0116-z |

| [93] |

A. Tiwari, S. Saraf, A. Verma, et al., World J. Gastroenterol. 24 (2018) 4428-4435. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v24.i39.4428 |

| [94] |

M. Greally, C.M. Kelly, A. Cercek, Curr. Prob. Cancer 42 (2018) 560-571. DOI:10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2018.07.001 |

| [95] |

A. Rosewell Shaw, C. Porter, G. Biegert, et al., Cancers (Basel) 14 (2022) 2769. DOI:10.3390/cancers14112769 |

| [96] |

E. Ponterio, R. De Maria, T.L. Haas, Front. Immunol. 11 (2020) 565631. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2020.565631 |

| [97] |

A. Rosewell Shaw, C.E. Porter, T. Yip, et al., Commun. Biol. 4 (2021) 368. DOI:10.1038/s42003-021-01914-8 |

| [98] |

M. Habban Akhter, N. Sateesh Madhav, J. Ahmad, Artif. Cell. Nanomed B 46 (2018) 1188-1198. DOI:10.1080/21691401.2018.1481863 |

| [99] |

H. Li, C. Yang, H. Cheng, et al., J. Cancer 12 (2021) 1804-1814. DOI:10.7150/jca.50509 |

| [100] |

C. Zhang, Z. Wang, Z. Yang, et al., Mol. Ther. 25 (2017) 1248-1258. DOI:10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.010 |

| [101] |

Y. Wang, M. Chen, Z. Wu, et al., Oncoimmunology 7 (2018) e1440169. DOI:10.1080/2162402X.2018.1440169 |

| [102] |

K.M. Hege, E.K. Bergsland, G.A. Fisher, et al., J. Immunother. Cancer 5 (2017) 22. DOI:10.1186/s40425-017-0222-9 |

| [103] |

J. Betge, N.I. Schneider, L. Harbaum, et al., Virchows Arch. 469 (2016) 255-265. DOI:10.1007/s00428-016-1970-5 |

| [104] |

S.A. Joosse, T.M. Gorges, K. Pantel, EMBO Mol. Med. 7 (2015) 1-11. DOI:10.15252/emmm.201303698 |

| [105] |

H. Lin, J. Cheng, W. Mu, et al., Front. Immunol. 12 (2021) 744823. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2021.744823 |

| [106] |

H. Torikai, A. Reik, P.Q. Liu, et al., Blood 119 (2012) 5697-5705. DOI:10.1182/blood-2012-01-405365 |

| [107] |

L. Poirot, B. Philip, C. Schiffer-Mannioui, et al., Cancer Res 75 (2015) 3853-3864. |

| [108] |

Y. Hu, Y. Zhou, M. Zhang, et al., Clin. Cancer Res. 27 (2021) 2764-2772. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3863 |

| [109] |

J. Li, D.J. Burgess, Acta Pharm. Sin. B 10 (2020) 2110-2124. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2020.05.008 |

| [110] |

S. Han, K. Huang, Z. Gu, et al., Nanoscale 12 (2020) 413-436. DOI:10.1039/C9NR08086D |

| [111] |

Y. Gong, R.G.J. Klein Wolterink, J. Wang, et al., J. Hematol. Oncol. 14 (2021) 73. DOI:10.1186/s13045-021-01083-5 |

| [112] |

S.E. Franks, B. Wolfson, J.W. Hodge, Cancers 12 (2020) 2131. DOI:10.3390/cancers12082131 |

| [113] |

F. Simonetta, M. Alvarez, R.S. Negrin, Front. Immunol. 8 (2017) 465. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00465 |

| [114] |

G. Ji, L. Ma, H. Yao, et al., Acta Pharm. Sin. B 10 (2020) 2171-2182. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2020.09.004 |

| [115] |

C.T. Petersen, G. Krenciute, Front. Oncol. 9 (2019) 69. DOI:10.3389/fonc.2019.00069 |

| [116] |

R.S. Huang, M.C. Lai, H.A. Shih, et al., J. Exp. Med. 218 (2021) e20201529. DOI:10.1084/jem.20201529 |

| [117] |

Y.R. Mohseni, S.L. Tung, C. Dudreuilh, et al., Front. Immunol. 11 (2020) 1608. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2020.01608 |

| [118] |

Y. Imura, M. Ando, T. Kondo, et al., JCI Insight 5 (2020) e136185. DOI:10.1172/jci.insight.136185 |

| [119] |

S. Wright, C. Hennessy, J. Hester, et al., Engineering 10 (2021) 30-43. |

| [120] |

A. Sicard, C. Lamarche, M. Speck, et al., Am. J. Transplant. 20 (2020) 1562-1573. DOI:10.1111/ajt.15787 |

| [121] |

Z. Zhao, Y. Chen, N.M. Francisco, et al., Acta Pharm. Sin. B 8 (2018) 539-551. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2018.03.001 |

| [122] |

J. Wei, Y. Liu, C. Wang, et al., Signal Transduct. Tar. 5 (2020) 1-9. DOI:10.1038/s41392-019-0089-y |

| [123] |

C. Li, Y. Zhang, Y. Wan, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 1615-1625. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.01.001 |

| [124] |

I.Y. Jung, J. Lee, Mol. Cells 41 (2018) 717. |

| [125] |

J. Salas-Mckee, W. Kong, W.L. Gladney, et al., Hum. Vacc. Immunother. 15 (2019) 1126-1133. DOI:10.1080/21645515.2019.1571893 |

| [126] |

T. Tang, X. Huang, G. Zhang, et al., Signal Transduct. Tar. 6 (2021) 1-13. DOI:10.1038/s41392-020-00451-w |

| [127] |

Q. Zeng, Z. Liu, T. Niu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107747. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.107747 |

| [128] |

Q. Xiao, X. Li, C. Liu, et al., Acta Pharm. Sin. B (2022). DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2022.07.012 |

2023, Vol. 34

2023, Vol. 34