b School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Institute for Computation in Molecular and Materials Science, Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing 210094, China;

c Institut Charles Gerhardt Montpellier, UMR-5253, Université de Montpellier, CNRS, ENSCM, Place E. Bataillon, Cedex 05, Montpellier 34095, France;

d Advanced Interdisciplinary Institute of Environment and Ecology, Beijing Normal University, Zhuhai 519087, China

Ammonia, as the basic chemical substance for the production of various synthetic chemicals such as chemical fertilizers, dyes and resins, plays an indispensable role in agriculture and industry [1-3]. The traditional preparation of ammonia is mainly based on the Haber-Bosch process, which operates under extremely harsh conditions (400–600 ℃ and 150–300 atm) [4-6], leading to the huge energy consumption and the massive emission of carbon dioxide [7,8]. To overcome such shortage of the Haber-Bosch method, the electrocatalysis of the N2-to-NH3 conversion paves a green and sustainable avenue for the ammonia synthesis under the mild reaction [9-12], wherein the performance is significantly depended on the efficiency of the catalyst used. Despite tremendous efforts in recent decades, electrocatalysts that selectively and efficiently reduce nitrogen to ammonia remain elusive. Therefore, the development of the highly-active materials for the ammonia synthesis has attracted great attention [13].

Among the varied catalysts, single-atom catalysts (SACs) with utmost atom-utilization efficiency and distinctive coordination environment have become a research hotspot toward the conversion from N2 into NH3 [14-16]. Such as, Zhang et al. demonstrated that FeN3 embedded graphene significantly promotes the electrocatalysis of nitrogen reduction reaction (NRR) wherein the rate determining step is the first protonation with the free energy change of 0.04 eV [17]. Similarly, Zhao et al. found that WN3 decorated graphene is a promising NRR electrocatalyst with the limiting potentials of 0.33 V [18]. As the graphene derivative, the VN3 embedded graphane shows good NRR performance via the enzymatic pathway with the free energy change of 0.28 eV [19]. Additionally, W anchored g-C3N4 exhibits the good activity toward NRR with a limiting potential of 0.35 V via associative enzymatic pathway [20]. The mentioned results indicate the fact that the carbon-based SACs with transition metal decoration as the active site delivers good activity toward N2-to-NH3 conversion.

Exception with the common carbon-based material mentioned above, the waves of renewed interest have turned to two-dimensional monoelemental structures due to its interesting physical and chemical properties [21,22]. It seems the group-VA elemental monolayer is attractive as an electrocatalyst for ammonia synthesis. As an illustration, Liu et al. found that W embedded black phosphorus have the onset potential of 0.42 V [23]. Furthermore, Xu et al. found the V doped arsenene provides an ultralow overpotential of 0.10 V via the enzymatic pathway [24]. Analogously, Song et al. demonstrated that NbP3 embedded arsenene has a low overpotential of 0.36 V via the distal mechanism [25]. Besides, Gu et al. discovered that anionic Os and Re metal centers on the defective antimonene can electrochemically catalyze the nitrogen reduction reaction with a limiting potential close to that of stepped Ru(0001) [26]. The similar conclusion has been drawn by Cao et al. that the antimonene increases the efficiency of NH3 production [27]. For the last group-VA elemental monolayer, bismuthene, it has been successfully synthesized [28,29], which possesses identical atomic structure in comparison with phosphorene, arsenene and antimonene. More encouragingly, Hao et al. discovered that the presence of bismuth nanocrystals and potassium cations in water significantly promotes nitrogen electroreduction to ammonia [30]. Based on the mentioned information, bismuthene might be a promising material for the N2-to-NH3 conversion. Therefore, we are naturally interested in whether the pristine bismuthene is active and whether transition metal decoration would boost the efficiency.

To address the mentioned issues, we systematically studied the catalytic activities of bismuthene with and without anchoring transition metal atom in the application of N2-to-NH3 electrocatalysis by means of the density functional theory (DFT) calculations. For simplification, it donates as TM@Bis wherein 3d/4d/5d TM are taken into consideration with the exception of Tc and Lu due to toxic or radioactive characteristic. Our results demonstrate that the pristine bismuthene fails to capture the N2 molecule, indicating its infeasibility to boost the N2-to-NH3 conversion. Furthermore, the strategy of transition metal decoration is a valid method to activate the inert bismuthene, wherein that W@Bis exhibits the best activity under the distal pathway with a small limiting potential UL of 0.26 V. More interestingly, a volcano curve is established between UL and TM d valence electrons wherein W with 4 electrons in d band has the minimum UL meanwhile either increase or decrease the number of valence electrons would enlarge the UL data. Such phenomenon originates from the underlying acceptance-back donation mechanism. Our study provides the theoretical prediction that the functional bismuthene is a feasible to improve the efficiency for the nitrogen electroreduction to ammonia.

All calculations are performed within the DFT framework as implemented in DMol3 code [31,32]. The generalized gradient approximation with the Perdew−Burke−Ernzerhof (PBE) functional is employed to describe exchange and correlation effects [33]. The DFT Semi-core Pseudopots (DSPP) core treat method is implemented for relativistic effects, which replaces core electrons by a single effective potential and introduces some degree of relativistic correction into the core [34]. The double numerical atomic orbital augmented by a polarization function (DNP) is chosen as the basis set [31]. A smearing of 0.005 Ha (1 Ha = 27.21 eV) to the orbital occupation is applied to achieve accurate electronic convergence. In the geometry structural optimization, the convergence tolerances of energy, maximum force and displacement are 1.0 × 10−5 Ha, 0.002 Ha/Å and 0.005 Å, respectively. The spin-unrestricted method is used for all calculations. A conductor-like screening model (COSMO) was used to simulate water solvent environment for all calculations [35]. COSMO is a continuum model in which the solute molecule forms a cavity within the dielectric continuum. The DMol3/COSMO method has been generalized to periodic boundary cases. The dielectric constant is set as 78.54 for H2O. As a representative, in order to verify the effect of water solution, the adsorption abilities of W@Bis and Nb@Bis with and without COSMO correction are tabulated in Table S1 (Supporting information) for comparison and the corresponding free energy profiles are presented in Figs. S1 and S2 (Supporting information). In line with the previous reports [36], such correction enhances the adsorption strengths and reduces the thermodynamic barriers, being benefiting for the reactants capture and protonation progress. Furthermore, a first principles molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation was performed to assess the thermodynamic stability at 300 K. A canonical ensemble (NVT) within Massive GGM thermostat scheme was used to control the temperature [37,38]. During the stimulation processes, a total simulation time was set to 3 ps with the time step of 1 fs. To check the sufficiency of the stimulation time adopted herein, we further perform another AIMD calculation on W@Bis with the stimulation time of 5 ps and the corresponding result is given in Fig. S3 (Supporting information). Consistently, no structural damage is observed for W@Bis, which is in line with the results drawn from the stimulation time of 3 ps. Therefore, we analyze our data on the basis of AIMD with 3 ps in the discussion.

The 15 Å-thick vacuum is added to avoid the artificial interactions between the catalyst and its images. The adsorption energies (Eads) of NRR intermediates are calculated by

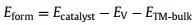

|

(1) |

where Esystem, Ecatalyst and Em represent the total energy of the adsorption system, the catalyst and the adsorbates, respectively.

To evaluate the thermodynamic stabilities of the designed TM embedded bismuthene, we calculated the binding energies Eb using the following equation, which has been extensively used in literatures [39]:

|

(2) |

where EV is the total energy of the catalyst without TM atoms and ETM is the total energy of the single TM atom.

To evaluate the energetic feasibility of the experimental synthesis, we calculated the formation energies Eform using the following equation [40]:

|

(3) |

where ETM-bulk is the total energy of the TM bulk.

Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) of the elementary steps was constructed based on the computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) model developed by Nørskov et al., where the chemical potential of (H+ + e−) pair in solution is equal to the half of the chemical potential of a gas-phase H2 [41-43]. The corresponding ΔG is determined by the following equation [44]:

|

(4) |

where ∆E is the energy difference, ∆ZPE indicates the change in zero point energy, and ∆S represents the change in the entropy, respectively. Herein, the temperature T is 298.15 K. The ZPE and S are calculated from the vibrational frequencies according to standard methods. Following the suggestion of Lim and Wilcox [45], in order to reduce the cumbersome calculation, the substrates are fully constrained for the frequency calculation. The term of ∆GU = – eU corresponds to the free energy contribution caused by the variation of electrode potential while ΔGpH is the pH correction of the free energy, being expressed as ΔGpH = – kTln10 × pH, where kB is the Boltzmann constant. In our case, pH is zero under the acid solution. ΔG < 0 corresponds to an exothermic adsorption process vice versa. The methods have been successfully applied for analyzing N2 fixation process, indicating its robustness and feasibility [46,47].

The limiting potential UL is determined by the following equation [48]:

|

(5) |

where ΔGPDS is the free energy change of the elementary step with the maximum endothermic character during the N2-to-NH3 conversion.

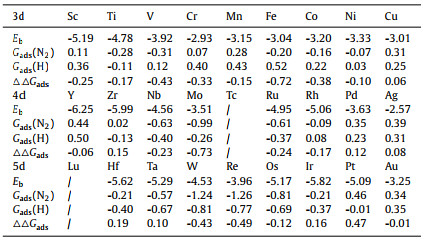

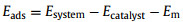

Fig. 1a describes the atomic configuration of the transition metal atom decorated bismuthene (TM@Bis) with one TM substitution. The binding energies Eb between TM and its surrounding are listed in Table 1. In the same period, the TM element with half-filling or full-filling d band delivers the local minimum Eb due to its stable electron configuration. Therein, the corresponding values are −2.93 and −3.01 eV for Cr and Cu, −3.51 and −2.57 eV for Mo and Ag, −3.96 and −3.25 eV for Re and Au, respectively. Since Eb > −1.5 eV indicates the intensive chemical interaction [17], it reveals that TM atom is firmly fixed in the bismuthene. In order to further reveal the strong interaction, Fig. 1b presents the partial density of states (PDOS) between TM d band and Bi p band of TM@Bis wherein the elements of Ti, V, Nb, Mo, W are taken as the illustration along with the information of pristine bismuthene. Wherein, the intensive pd coupling between TM decoration and its Bi ligand as well as the descended p band of Bi ligand clearly supports the formation of the chemical TM-Bi bonds. Furthermore, the TM dopant enriches the electron occupation at Fermi energy, being beneficial for the electron transfer, another advantage for the application of electrocatalysis [49,50]. In addition, the formation energies Eform of TM@Bis are further evaluated in order to illustrate the synthesis feasibility and the values are tabulated in Table S2 (Supporting information). Exception with the dopants of Sc, Y, Pd, Ag and Au, the rest ones possess the positive Eform values. It indicates that the formation of TM@Bis is an endothermic process and needs the extra energy provided. However, the similar systems, such as Ru/g-C3N4, Pt/g-C3N4, Fe/N-G and Co/N-G, have been experimentally prepared and their Eform values are 3.12, 2.88, 2.26 and 2.27 eV, respectively [40,51-54]. To a certain extent, the comparable value in the same order of magnitude implies that the synthesis of TM@Bis is feasible from the energetic aspect. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe its realization due to the advanced experimental technology.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. (a) The schematically atomic structure of TM@Bis. (b) The partial density of states (PDOS) between TM d band and Bi p band for TM@Bis. (c) The difference of adsorption free energy between H and N2, △△Gads = Gads(N2) – Gads(H). (d) The free energy change of the first protonation step △G(*N2→*NNH) and the free energy change last protonation step △G(*NH2→*NH3). | |

|

|

Table 1 The binding energies Eb, the adsorption free energies Gads(N2) and Gads(H), the difference △△Gads between Gads(N2) and Gads(H). (Eb, Gads(N2), Gads(H) and △△Gads in eV). |

Before the activity investigation, the adsorption of N2 molecule is considered and the corresponding free energies Gads(N2) are listed in Table 1. The pristine bismuthene is unable to capture the N2 molecule due to the endothermic Gads(N2), indicating it is inactive toward ammonia production. Furthermore, the similar situations are found for Sc@Bis, Cr@Bis, Mn@Bis, Cu@Bis, Y@Bis, Zr@Bis, Ag@Bis, Pd@Bis, Pt@Bis and Au@Bis, respectively. Therefore, the mentioned systems are ruled out for further consideration. In addition to the good affinity toward N2 molecule, the relative weaker H adsorption is necessary to address the critical competition of the undesirable hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) in aqueous solutions [55-57]. Herein, the difference of adsorption free energies between N2 molecule and H is adopted for the first step of quick screening, that is, △△Gads = Gads(N2) – Gads(H), wherein the negative value indicates the preferred NRR selectivity over HER, visa verse. Fig. 1c reveals that the NRR efficiency of Hf@Bis, Ta@Bis and Ir@Bis would be suppressed by the competition of side HER process. However, the rest configurations would offer good NRR selectivity, involving Ti@Bis, V@Bis, Fe@Bis, Co@Bis, Ni@Bis, Nb@Bis, Mo@Bis, Ru@Bis, Rh@Bis, W@Bis, Re@Bis and Os@Bis. Subsequently, we focus our attention on the free energy changes of the first protonation and the sixth protonation since the potential-determining step (PDS) is generally located at either the first protonation (*N2 + H+ + e– → *NNH) or the sixth protonation (*NH2 + H+ + e– → *NH3) [47,58]. Fig. 1d demonstrates that the elements of Ti, V, Nb, Mo, W and Os would be promising dopants due to the possibility of low thermodynamic barriers if artificially setting the values less than 0.55 eV as our reference according to the previous reports [43,59,60].

To confirm the efficiency of the N2-to-NH3 conversion, we perform the analysis of the whole reaction pathways and the free energy changes of elementary steps are given in Table 2. There are three feasible reaction pathways involving distal, alternative and enzymatic pathways [61-63]. For the distal mechanism, three proton-electron pairs (H+ + e−) first react with the outermost N atom to form the first NH3 molecule, and with that, the remaining N atom undergoes subsequent hydrogenation until the release of second NH3 molecule. While for the alternating mechanism, the proton-electron pairs alternatively attack the two N atoms, generating the two NH3 molecules one after another. The reduction of the side-on adsorbed N2 proceeds through the enzymatic mechanism, in which two N atoms are hydrogenated by proton-electron pairs alternately, and two NH3 molecules will be released consecutively. Herein, it is noteworthy that the continuous protonation progress is from the adsorbed N-containing intermediates reacted with the protons in the solution [47,64-67]. It is a universal and valid method for the proton treatment adopted by the calculations. Therefore, we do not consider the co-adsorption of NRR intermediates and *H specie.

|

|

Table 2 The free energy change ΔG (ΔG in eV). Ri stands for the ith protonation step. |

As a representative, Fig. 2 shows the free energy profiles of W@Bis via distal mechanism, alternating mechanism and enzymatic mechanism, respectively. For continuous protonation via the distal mechanism, the free energy changes of the elementary steps ΔG are 0.16, –0.32, –1.1, –0.29, 0.25 and 0.26 eV, respectively. The maximum endothermic step is located at the last protonation step of *NH2 + H+ + e– → *NH3. Therefore, the PDS is identified as the *NH3 formation and the corresponding thermodynamic barrier ΔGPDS is 0.26 eV. Similarly, ΔG of the protonation steps are 0.16, 0.86, –0.59, 0.54, –2.26 and 0.26 eV under the alternating pathway wherein the PDS is the second protonation step of *NNH + H+ + e– → *NHNH and ΔGPDS is 0.86 eV. Furthermore, the ΔG are 0.24, 0.35, −0.61, 0.46, −2.12 and 0.26 eV along enzymatic mechanism, respectively. Since the step of *NH*NH2 + H+ + e– → *NH2*NH2 encounters the greatest energy barriers of 0.46 eV, the fourth protonation step is regarded as the PDS of enzymatic mechanism. Herein, we notice that the *NH3 desorption is upshifted energetically and it needs to overcome a barrier of 2.27 eV. In accord with the previous works, the endothermic characteristic of NH3 desorption is a universal phenomenon. To remove its adsorption and recover the active site, the formed *NH3 could be further hydrogenated to NH4+ and readily leave the electrode with the aid of strongly acidic aqueous solution [64,68-70]. Therefore, with aid of the solution [71,72], the *NH3 desorption is not a problematic obstacle in NRR. As a result, distal mechanism with lowest thermodynamic barrier is more favorable for NRR electrocatalysis. In the regard, the N2-to-NH3 convention catalyzed by W@Bis material is energetically favored under the limiting potential UL of 0.26 V. As a supplementary, the NRR activity of W adsorption is further investigated since surface decoration via adsorption is another well-established method to provide the active site for electrocatalysis. According to the free energy profiles presented in Fig. S4 (Supporting information), the limiting potential UL is 0.51 V, being much higher than 0.26 V offered by the W substitution. Therefore, W substitution is more valid to boost ammonia synthesis.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) The free energy profiles of W@Bis via distal pathway. (b) The free energy profile of W@Bis via alternating pathway. (c) The free energy profile of W@Bis via enzymatic pathway. | |

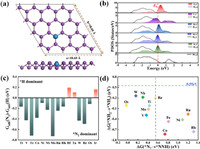

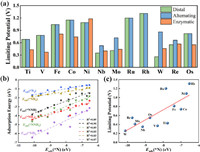

The free energy profiles of the rest systems are supplemented in Figs. S5–S15 (Supporting information). According to the same analysis, we summarize the ΔG of the protonation steps in Table 2 and present the UL data of varied TM@Bis in Fig. 3a. It is noteworthy that we do not consider the enzymatic mechanism on Ru@Bis and Rh@Bis due to the unfeasible characteristic of *N2 side-on adsorption [73]. Herein, the NRR catalyzed by Mo, Nb, W and Re dopants prefer the distal mechanism and the UL values are 0.41, 0.35, 0.26 and 0.55 V, respectively. Furthermore, the NRR catalyzed by Ni, Ru and Rh sites are through alternating pathway with the large UL of 1.09, 1.20 and 1.31 V, respectively, indicating the poor activities. Additionally, the NRR catalyzed by Ti, V, Fe, Co and Os dopants prefer enzymatic mechanism with the UL of 0.43, 0.37, 0.81, 0.74 and 0.55 V, respectively. According to the UL data, the NRR efficiency is in the order of W@Bis > Nb@Bis > V@Bis > Mo@Bis > Ti@Bis > Re@Bis = Os@Bis > Co@Bis > Fe@Bis > Ni@Bis > Ru@Bis > Rh@Bis. As a supplementary, the UL comparison (or reduction potential) between NRR and HER are listed in Table S3 (Supporting information). The data further confirms the good efficiency of the W@Bis endowed with a significantly smaller UL of NRR vs HER. Furthermore, the dopants of Re and Os are also promising candidates for experimental synthesis due to its good selectivity, in despite of the slightly higher UL of NRR. On the contrary, the NRR activity of TM@Bis with the rest dopant might be suffered from the undesirable side reaction. Besides the activity, Table 2 reveals that the PDS under the energetically preferred pathway is the last protonation for W@Bis mentioned above and it turns to the first protonation for the rest ones with the exception of Os@Bis located at the second protonation. On the basis of Sabatier principle, it implies that the NRR activity of the former slightly suffers from the strong affinity toward NRR intermediates meanwhile the latter provides the insufficient activation ability. Fig. 3b presents the universal linear relation of the adsorption energies Eads among varied NRR intermediates, being stemmed from the similar adsorption configuration [74,75]. Herein, the adsorption affinity of TM@Bis could be presented by the *N adsorption energy Eads(*N). Furthermore, Fig. 3c reveals the monotonic scaling between UL and Eads(*N) wherein the TM@Bis endowed with the stronger Eads(*N) offers better performance for N2 electroreduction into NH3. Therefore, our results are in accord with our conjecture that the thermodynamic limitation is posed by the correlations among the adsorption of varied NRR intermediates, which is prevalent phenomenon for SAC with TM active site [27,76].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) The summary of the limiting potentials UL. (b) The fitting of adsorption energy of NRR intermediates as a function of the *N adsorption energy Eads(*N). (c) The fitting of limiting potentials UL as a function of the *N adsorption energy Eads(*N). | |

According to the mentioned information, W@Bis performs best toward ammonia generation herein. As previous reported, the W dopant embedded different substrates have been discovered to efficiently catalyze nitrogen fixation. For example, the UL values are 0.33, 0.35 and 0.42 V for the W supported on the N doped graphene, g-C3N4 and black phosphorus, respectively [18,20,23]. It seems a similar good performance of W dopant as the active site. In order to reveal the underlying origin of its universality mentioned above, Fig. 4a schematically shows the integral partial density of states of N2 adsorption on W@Bis as an illustration. Wherein, the electrons contributed by the d-band of W@Bis disturb the N≡N π bond, which makes the N2 bond longer and activated. Spontaneously, the electron returns to the d band again. It is well-known as the acceptance-back donation mechanism. It implies that the metal atom in the middle range of Periodic Table would deliver relative better NRR performance, because its partial filling d band has the ability to release electrons and host electrons. On the contrary, the nearly empty d band of early transition metal element limits the electron transfer from the active site to the reactant meanwhile the almost full d band of the late transition metal element suffers from the electron transfer from the reactant to the active site. The mechanism is in line with our data, that is, the W dopant in the middle range offer relative smaller UL in comparison with the early transition metal elements such as Ti and late transition metal elements such as Fe, Co and Ni. To confirm this view, the fitting between the number of valence electrons and UL data is performed in Fig. 4b. There is a volcano curve with the W@Bis suited at the summit. That is, W with 4 electrons in d band have the minimum limit potentials of 0.26 V. Either increase or decrease the number of valence electrons would enlarge the UL data. The final question is why Nb@Bis delivers slightly inferior performance in comparison with W@Bis since W and Nb have the identical valence electrons in d band. As discussed above, the NRR performances of Nb@Bis and W@Bis separately suffer from the thermodynamic barriers of the first and last protonation steps, which originate from the diffident adsorption ability. The reduced reactivity of Nb@Bis is clearly revealed by the PDOS between W/Nb d band and N p band shown in Fig. 4c wherein the pd hybridization of Nb@Bis is relative weaker in comparison with W@Bis, being in line with the trend of the affinity toward NRR intermediates, as reflected by the Eads listed in Table S1 (Supporting information). It is the reason why the activities of Nb@Bis and W@Bis are different as mentioned above. Furthermore, to gain deep insight into the effect of W@Bis during continuous protonation progress, the electron transfers are analyzed in detail wherein three moieties are artificially divided and displayed in Fig. 4d, involving the adsorbates NxHy (moiety 1), the TMBi3 site (moiety 2) and the bismuthene support (moiety 3). Fig. 4e illustrates the Mulliken charges during the protonation progress, indicating that good conductivity of W@Bis enables the effective electron transfers. More specifically, the electron communications are occurred between the bismuthene support and NRR intermediates meanwhile the electron fluctuation of moiety 2 is negligible [77]. That is, moiety 3 is an electron reservoir and moiety 2 acts as an electron transmitter [19,78].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (a) The integral partial density of states (PDOS) of N2 adsorption on W@Bis. (b) The volcano correlation between the number of valence states (electrons) and limiting potential UL. (c) The partial density of states (PDOS) between W/Nb d band and N p band for W@Bis and Nb@Bis with *N adsorption. (d) The schematically plot of the three moieties. (e) The Mulliken charge variation of W@Bis via distal pathway. (f) The variations of the system energy and the bond lengths d between W and its surrounding Bi ligand during the molecular dynamic stimulation of W@Bis at 300 K. Insert: the atomic structures captured at every ps, respectively. | |

Before closing our discussion, we pay our attention on the stability of W@Bis, another important factor for catalyst design. Considering the possibility of the structural deformation caused by the adsorbates, Table S4 (Supporting information) presents the variation of W-Bi bond lengths caused by the adsorption. Clearly, the adsorption leads to the elongation of W-Bi bonds. However, the changes of average bond length are within 0.2 Å and the W-Bi bonds keep binding under the adsorption. Furthermore, the PDOS presented in Fig. S16 (Supporting information) provides the evidence to support the strong fixation of W atom wherein the overlapping of pd orbitals is consistently observed below the Fermi energy level, indicating the maintenance of covalent W-Bi bonds, in line with the small variation of bond lengths. Therefore, the W@Bis configuration will not be destroyed by the adsorbates. Moreover, we perform a first principles molecular dynamics simulation with a constant temperature of T = 300 K, in order to ensure the thermodynamic stability of W@Bis at the room temperature. Fig. 4f demonstrates that the atomic structure is well preserved during the simulation, as reflected by the monitoring of the bond length dW-Bi between W and its surrounding Bi atoms. Despite the observed fluctuation, no breaking of W-Bi bonds is found, indicating the good resistance against the structural collapse. However, a slight deformation of atomic configuration of Nb@Bis is observed in Fig. S17 (Supporting information), indicating its inferior stability referring to W@Bis. Therefore, W@Bis endowed with its high efficiency and good stability is a promising candidate for ammonia synthesis.

In a summary, the catalytic performance of TM@Bis toward N2 electroreduction to NH3 is systematically evaluated by means of density functional theory calculations. Based on the free energy profiles, the efficiency is in the order of W@Bis > Nb@Bis > V@Bis > Mo@Bis > Ti@Bis > Re@Bis = Os@Bis > Co@Bis > Fe@Bis > Ni@Bis > Ru@Bis > Rh@Bis, wherein the thermodynamic barriers are 0.26, 0.35, 0.37, 0.41 0.43, 0.55, 0.55, 0.74, 0.81, 1.09, 1.2 and 1.31 eV, respectively. The PDS under the energetically preferred pathway is the last protonation for W@Bis and it turns to the first protonation for the rest ones with the exception of Os@Bis located at the second protonation. It indicates that the NRR performance of the former slightly suffers from the strong affinity toward NRR intermediates meanwhile the latter provides the insufficient activation ability. In addition, the best performance offered by the W dopant stems from the underlying acceptance-back donation mechanism. Therefore, our work offers promising candidates for the experimental synthesis and provides a fundament understanding for the material design for nitrogen reduction electrocatalysis. It represents an efficient and sustainable ammonia synthesis from nitrogen with broad scientific impacts.

Declaration of competing interestThere are no conflicts to declare.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors greatly acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21503097, 52130101, 51701152, 21806023 and 51702345) and China Scholarship Council (No. 202008320215).

Supplementary materialsThe Supporting information is available on line, including details of adsorption energy, formation energy, free energy profile, limiting potential and bond length. Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.07.002.

| [1] |

V. Rosca, M. Duca, M.T. De Groot, M.T.M. Koper, Chem. Rev. 109 (2009) 2209-2244. DOI:10.1021/cr8003696 |

| [2] |

S.L. Zhao, X.Y. Lu, L.Z. Wang, J. Gale, R. Amal, Adv. Mater. 31 (2019) 1805367. DOI:10.1002/adma.201805367 |

| [3] |

L. Zhang, L. Ding, G. Chen, X. Yang, H. Wang, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 2612-2616. DOI:10.1002/anie.201813174 |

| [4] |

W. Guo, K. Zhang, Z. Liang, R. Zou, Q. Xu, Chem. Soc. Rev. 48 (2019) 5658-5716. DOI:10.1039/c9cs00159j |

| [5] |

L. Huang, X. Gu, G. Zheng, Chem 5 (2019) 15-17. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2018.12.015 |

| [6] |

C.Y. Ling, Y.H. Zhang, Q. Li, X.W. Bai, J.L. Wang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 18264-18270. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b09232 |

| [7] |

F. Jiao, B. Xu, Adv. Mater. 31 (2018) 1805173. |

| [8] |

M. Kitano, Y. Inoue, Y. Yamazaki, et al., Nat. Chem. 4 (2012) 934-940. DOI:10.1038/nchem.1476 |

| [9] |

D. Bao, Q. Zhang, F.L. Meng, et al., Adv. Mater. 29 (2017) 1604799. DOI:10.1002/adma.201604799 |

| [10] |

F. Zhou, L.M. Azofra, M. Ali, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 10 (2017) 2516-2520. DOI:10.1039/C7EE02716H |

| [11] |

S. Zhang, Y.X. Zhao, R. Shi, C. Zhou, Adv. Energy Mater. 10 (2020) 1901973. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201901973 |

| [12] |

S. Wu, M. Zhang, S. Huang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107282. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.005 |

| [13] |

Y. Yang, Y. Tang, H. Jiang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 30 (2019) 2089-2109. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2019.10.041 |

| [14] |

S. Yuan, B. Xu, S. Li, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2023) 399-403. DOI:10.1007/978-981-99-1365-7_31 |

| [15] |

L. Chen, C. He, R. Wang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 53-56. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.11.013 |

| [16] |

J. Guo, T.T. Tsega, I.U. Islam, A. Iqbal, X. Qian, Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 2487-2490. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.02.019 |

| [17] |

S. Zhang, M. Wang, S. Jiang, H. Wang, ChemistrySelect 6 (2021) 1787-1794. DOI:10.1002/slct.202100057 |

| [18] |

W. Zhao, L. Chen, W. Zhang, J. Yang, J. Mater. Chem. A 9 (2021) 6547-6554. DOI:10.1039/d0ta11144a |

| [19] |

B.B. Xiao, L. Yang, L.B. Yu, E.H. Song, Q. Jiang, Appl. Surf. Sci. 513 (2020) 145855. DOI:10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.145855 |

| [20] |

Z. Chen, J. Zhao, C.R. Cabrera, Z.J. Chen, Small Methods 3 (2019) 1800368. DOI:10.1002/smtd.201800368 |

| [21] |

M. Fan, X. Liang, Q. Li, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 207275. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.02.080 |

| [22] |

Y. Wang, W. Feng, Y. Chen, Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 937-946. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2019.11.016 |

| [23] |

K. Liu, J. Fu, L. Zhu, X. Zhang, M. Liu, Nanoscale 12 (2020) 4903-4908. DOI:10.1039/c9nr09117c |

| [24] |

Z. Xu, R. Song, M. Wang, et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22 (2020) 26223-26230. DOI:10.1039/d0cp04315j |

| [25] |

R. Song, J. Yang, M. Wang, Z. Shi, Z. Xu, ACS Omega 6 (2021) 8662-8671. DOI:10.1021/acsomega.1c00581 |

| [26] |

J. Gu, Y. Zhao, S. Lin, et al., J. Energy Chem. 63 (2021) 285-293. DOI:10.1016/j.jechem.2021.08.004 |

| [27] |

S. Cao, Y. Sun, S. Guo, Z. Guo, F. Jiang, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13 (2021) 40618-40628. DOI:10.1021/acsami.1c10967 |

| [28] |

F. Reis, G. Li, L. Dudy, et al., Science 357 (2016) 287-290. |

| [29] |

A. Fang, C. Adamo, S. Jia, et al., Sci. Adv. 4 (2018) eaaq0330. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.aaq0330 |

| [30] |

Y.C. Hao, Y. Guo, L.W. Chen, et al., Nat. Catal. 2 (2019) 448-456. DOI:10.1038/s41929-019-0241-7 |

| [31] |

B. Delley, J. Chem. Phys. 92 (1990) 508-517. DOI:10.1063/1.458452 |

| [32] |

B. Delley, J. Chem. Phys. 113 (2000) 7756-7764. DOI:10.1063/1.1316015 |

| [33] |

J.P. Perdew, K. Burke, M. Ernzerhof, Phys. Rev. Lett. 77 (1996) 3865-3868. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865 |

| [34] |

B. Delley, Phys. Rev. B 66 (2002) 155125. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevB.66.155125 |

| [35] |

T. Todorova, B. Delley, Mol. Simulat. 34 (2008) 1013-1017. DOI:10.1080/08927020802235672 |

| [36] |

P. Zhang, Z. Wang, L. Liu, et al., Appl. Mater. Today 14 (2019) 151-158. DOI:10.1016/j.apmt.2018.12.003 |

| [37] |

S. Nosé, J. Chem. Phys. 81 (1984) 511. DOI:10.1063/1.447334 |

| [38] |

L. Yang, S. Feng, W. Zhu, J. Chem. Phys. Lett. 13 (2022) 1726-1733. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpclett.2c00044 |

| [39] |

C. Cui, H. Zhang, Z. Luo, Nano Res. 13 (2020) 2280-2288. DOI:10.1007/s12274-020-2847-0 |

| [40] |

H. Niu, X.T. Wang, C. Shao, Z.F. Zhang, Y.Z. Guo, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8 (2020) 13749-13758. DOI:10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c04401 |

| [41] |

J.K. Nørskov, J. Rossmeisl, A. Logadottir, et al., J. Chem. Phys. B 108 (2004) 17886-17892. DOI:10.1021/jp047349j |

| [42] |

A. Kulkarni, S. Siahrostami, A. Patel, J.K. Nørskov, Chem. Rev. 118 (2018) 2302-2312. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00488 |

| [43] |

J.H. Montoya, C. Tsai, A. Vojvodic, J.K. Nørskov, ChemSusChem 8 (2015) 2180-2186. DOI:10.1002/cssc.201500322 |

| [44] |

J. Wang, M. Shi, G. Yi, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 4623-4627. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.12.040 |

| [45] |

D.H. Lim, J. Wilcox, J. Chem. Phys. C 116 (2012) 3653-3660. DOI:10.1021/jp210796e |

| [46] |

C. Choi, S. Back, N.Y. Kim, et al., ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 7517-7525. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.8b00905 |

| [47] |

J. Zhao, Z. Chen, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 12480-12487. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b05213 |

| [48] |

X. Zheng, Y. Liu, Y. Yan, X. Li, Y. Yao, Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 1455-1458. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.08.102 |

| [49] |

D. Han, X. Liu, J. Cai, Y. Xie, Y. Qian, J. Energy Chem. 59 (2020) 55-62. |

| [50] |

W. Yang, H. Huang, X. Ding, Z. Ding, Z. Gao, Electrochim. Acta 335 (2020) 135667. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2020.135667 |

| [51] |

S.B. Tian, Z.Y. Wang, W.B. Gong, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 11161-11164. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b06029 |

| [52] |

X.G. Li, W.T. Bi, L. Zhang, S. Tao, Y. Xie, Adv. Mater. 28 (2016) 2427-2431. DOI:10.1002/adma.201505281 |

| [53] |

D.H. Deng, X.Q. Chen, L. Yu, et al., Sci. Adv. 1 (2015) 1500462. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.1500462 |

| [54] |

H.L. Fei, J.C. Dong, M. Arellano-Jiménez, et al., Nat. Commun. 6 (2015) 8668. DOI:10.1038/ncomms9668 |

| [55] |

C.Y. Ling, Y.X. Ouyang, Q. Li, et al., Small Methods 3 (2019) 1800376. DOI:10.1002/smtd.201800376 |

| [56] |

X. Liu, Y. Jiao, Y. Zheng, M. Jaroniec, S.Z. Qiao, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 9664-9672. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b03811 |

| [57] |

A. Maibam, S. Krishnamurty, J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 600 (2021) 480-491. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2021.05.027 |

| [58] |

Z.W. Chen, J.M. Yan, Q. Jiang, Small Methods 3 (2019) 1800291. DOI:10.1002/smtd.201800291 |

| [59] |

E. Tayyebi, Y. Abghoui, E. Skulason, ACS Catal. 9 (2019) 11137-11145. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.9b03903 |

| [60] |

C.W. Xiao, R.J. Sa, Z.J. Ma, et al., Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46 (2021) 10337-10345. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.12.148 |

| [61] |

K. Yuan, D. Lützenkirchen-Hecht, L.B. Li, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 2404-2412. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b11852 |

| [62] |

Z. Xu, C. An, Z. Zhang, Z. Zhou, J. Mater. Chem. A 6 (2018) 18599-18604. DOI:10.1039/C8TA07683A |

| [63] |

G. Zheng, L. Li, S. Hao, X. Zhang, Z. Tian, L. Chen, Theory Simulat. 3 (2020) 2000190. DOI:10.1002/adts.202000190 |

| [64] |

Z.W. Seh, J. Kibsgaard, C.F. Dickens, et al., Science 355 (2017) eaad4998. DOI:10.1126/science.aad4998 |

| [65] |

C. Liu, Q. Li, C. Wu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 2884-2888. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b13165 |

| [66] |

Z.X. Wei, Y.F. Zhang, S.Y. Wang, C.Y. Wang, J.M. Ma, J. Mater. Chem. A 6 (2018) 13790-13796. DOI:10.1039/C8TA03989E |

| [67] |

W. Song, J. Wang, L. Fu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 3137-3142. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.02.043 |

| [68] |

B.Y. Ma, Y. Peng, D.W. Ma, Z. Deng, Z.S. Lu, Appl. Surf. Sci. 495 (2019) 143463. DOI:10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.07.205 |

| [69] |

S. Ji, Z.X. Wang, J.X. Zhao, J. Mater. Chem. A 7 (2019) 2392-2399. DOI:10.1039/c8ta10497b |

| [70] |

H.J. Chun, V. Apaja, A. Clayborne, K. Honkala, J. Greeley, ACS Catal. 7 (2017) 3869-3882. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.7b00547 |

| [71] |

Y. Tan, Y. Xu, Z.M. Ao, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22 (2020) 13981-13988. DOI:10.1039/d0cp01963a |

| [72] |

C. Changhyeok, B. Seoin, N.Y. Kim, et al., ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 7517-7525. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.8b00905 |

| [73] |

P.Y. Du, Y.H. Huang, G.Q. Zhu, et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24 (2022) 2219-2226. DOI:10.1039/d1cp04926g |

| [74] |

E. Skulason, T. Bligaard, S. Gudmundsdottir, et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14 (2012) 1235-1245. DOI:10.1039/C1CP22271F |

| [75] |

D.W. Ma, Z.P. Zeng, L.L. Liu, XW. Huang, Y. Jia, J. Phys. Chem. C 123 (2019) 19066-19076. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b05250 |

| [76] |

X. Cui, C. Tang, Q. Zhang, Adv. Energy Mater. 8 (2018) 1800369. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201800369 |

| [77] |

Z.G. Wang, H.H. Wu, Q. Li, et al., Adv. Sci. 7 (2019) 1901382. |

| [78] |

X.W. Zhai, L. Li, X. Liu, et al., Naloscale 12 (2020) 10035-10043. DOI:10.1039/d0nr00030b |

2023, Vol. 34

2023, Vol. 34