b Guangling College and School of Horticulture and Plant Protection, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou 225009, China;

c College of Life and Environmental Science, Wenzhou University, Wenzhou 325035, China;

d Center of Super-Diamond and Advanced Films (COSDAF), City University of Hongkong, Hong Kong, China

In the recent 15 years, the use of antibiotics has soared by nearly 40% in the worldwide, while over 50% of antibiotics are abused [1]. Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) as a typical sulfonamide antibiotic, exhibits excellent inhibition on Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and indeed keeps humans and animals healthy from bacterial infections [2,3]. However, owing to the incomplete metabolism and relatively high stability, SMX is not readily eliminated by natural degradation and extensively detected in natural water. The toxicity and antibiotic-resistant bacteria of SMX impose adverse effects on ecological system.

In terms of antibiotic decontamination, multiple attempts have been made in carbon-based persulfate advanced oxidation processes (PS-AOPs) [4,5]. Persulfate are comprised of peroxymonosulfate (PMS, HSO5–) and peroxydisulfate (PS, S2O82–). Compared with PMS, PS possesses the higher oxidation potential (2.01 V vs. 1.82 V of PMS), lower cost, higher stability as well as fewer transportation problems. As a promising alternative to transition-metal-based catalyst, advantages including easy availability, porous structure, zigzag/armchair edges, defective sites, and abundant active functional groups, endow the carbonaceous materials with superb catalytic nature [6]. In the meanwhile, the problem about secondary contamination caused by toxic metal leaching can be avoided [7]. Furthermore, in carbon-driven persufate activation, the dominant nonradical pathways can be classified into surface activated complex, singlet oxygen, and electron transfer mediation [8,9]. They show high selectivity toward electron-rich compounds, and can retain excellent reactivity in complex aquatic matrix regardless of inorganic anions and radical scavenger. Therefore, developing efficient carbocatalysts to pursue maximum efficiency of PS-AOPs is highly desired.

Recently, carbon materials with defined heteroatom doping (N, S, Si, Se, B, P, I) into hexagonal skeleton have become prominent members in the carbon family [6,10-13]. Co-doping N with other heteroatoms is viewed as an effective strategy to enhance the catalytic performance [14]. For example, the catalytic activity of N, S-co-doped graphene was superior to that of single N or S doping one [15]. Owing to the electron-rich feature and large electronegativity (3.04 of N vs. 2.55 of C), the dope N can redistribute charge density and spin density of carbon atoms, thus breaking the chemical inertness of carbon network [16]. As a result of large atomic size (1.04 Å of S vs. 0.77 Å of C), replacing certain carbon lattice with S can change the local carbon geometry configuration and create structural defects, which can induce the generation of 1O2 [17]. The coupling effect of N and S creates more defective sites, tunes the electronic structures, and thus boosts the catalysis, but it needs precise control of N/S doping content [18]. It must be pointed out that excessive N/S doping may play an opposite role on catalytic performance. In addition, simultaneous introduction of N and B is prone to form N-B bond via one-step synthesis, resulting in a neutralization effect and deteriorating the catalytic capacity [19]. Although the reverse situation can be obtained with two-step strategies, it involves complex treatment [20]. Moreover, their catalytic durability is still unsatisfactory. Therefore, it is indispensable to develop an advanced heteroatom doping system.

S and B atoms may be two of the prospect candidates for co-doping carbon materials. The virtues of S and B doping are as follows: (1) Owing to the electron-deficient property caused by a vacant p orbit, B-doping enables the Fermi energy level to shift the guide band, which can accelerate the electron transfer reaction on the surface of carbon material [21]. (2) Considering the lower electronegativity of B instead of C (ΧB = 2.04 < XC = 2.55), the incorporation of B can change the charge density and electronic structure of carbon network [22]. (3) As similar to S, defects and imperfections can be introduced by B-doing into carbon lattice [23]. (4) The doped B as Lewis acid site can bind organic molecules, and contributes the cooperative pollutant degradation by adsorption and oxidation [24]. (5) In the case of S and B co-doping, the neutralization effect similar to N and B does not exist [25]. (6) Thiophene S can serve as Lewis basic site and medium to transfer electrons to O—O bind of persulfate, leading to PS activation [26]. However, to the best of our knowledge, S,B-co-doped carbon materials have not been reported to activate PS for contaminants degradation. Besides, the identification of active sites about B-containing functional (BC3, BC2O, and BCO2) groups needs further exploration.

Herein, S,B-co-doped carbon materials were synthesized by one-step calcination method. Sodium lignosulfonate served as both carbon and sulfur sources, and boric acid acted as boron source. Sodium chloride was used as salt template to facilitate the formation of porous structures. SEM, TEM, FT-IR, BET, Raman, and XPS were employed to characterize the catalysts. The catalytic performance was evaluated with sulfamethoxazole (SMX) as model contaminant and PS as the reactant. Reaction parameters, including PS dosage, catalyst dosage, SMX concentration, pH, inorganic anions, real water matrix, and other pollutants were investigated. Moreover, the catalyst reusability, degradation pathways and the toxicity of degradation system were also investigated. The catalytic mechanism was determined in line with the quenching experiments, EPR and electrochemical analysis. The active sites were identified by XPS and Raman spectroscopy before and after reaction. This work focuses on the catalytic performance improvement through the coupling effect of S,B-co-doping, and provides a new perspective to fabricate carbonaceous persulfate activators.

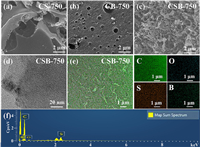

The reagents, material preparation, and experimental procedures were described in Texts S1-S3 (Supporting Information). Fig. 1 and Fig. S1 (Supporting information) displayed the SEM and HRTEM image of as-synthesized carbon materials. All the six components presented rough and wrinkled morphology. Apparently, the S-containing catalysts (CS-750 and CSBs) had more pores compared with single B-doped catalyst CB-750 (Figs. S1a-f). This was probably ascribed to the larger atomic radius of S than B and C (S: 1.02 Å > B: 0.82 Å and C: 0.77 Å), which could cause the distortion of carbon network and collapse of porous structure [27]. From the HRTEM results (Fig. 1d), the lattice stripe of CSB-750 was absent, implying the amorphous structure. The elemental distribution and surface morphology of CSB-750 were further investigated by energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) (Figs. 1e and f). The uniform distribution of four elements C, O, S, and B on the catalyst surface demonstrated the successful heteroatom doping.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. SEM images of CS-750 (a), CB-750 (b) and CSB-750 (c); HRTEM images of CSB-750 (d); Corresponding EDS elemental mappings of C, O, S and B (e); EDS map sum spectrum for CSB-750 (f). | |

XRD analysis was utilized to characterize the crystal structures of carbocatalysts (Fig. 2a). All samples exhibited similar diffraction patterns with two broad peaks. Among them, the strong peak located at 24° was attributed to the (002) plane of the amorphous carbon and the weak peak located at 44° was assigned to the (100) plane of the crystalline carbon. These analogous diffraction peaks implied that B-doping and elevating calcination temperature did not change the crystal structure of carbon materials.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. XRD patterns (a), N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms (b), pore size distribution (c), Raman spectra (d, e), and FT-IR spectra (f) of all samples; Content of thiophene sulfur and oxidized sulfur pecies (C-SOX-C) (g); Content of three boron species (h). | |

The specific surface area and pore structure were determined by N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms. The detailed BET and pore size parameters were summarized in Table S1 (Supporting information). As depicted in Fig. 2b, all catalysts exhibited a type Ⅳ isotherm curve with a noticeable hysteresis loop, indicating the existence of mesopores [28]. This case was in accordance with the pore size distribution range of 1.95–6.66 nm (Fig. 2c). The formation mechanism of the porous structure was proposed. One of the reasons was that the gas volatilization derived from organic components decomposition passed through the carbon layer, leaving a lot of tunnels and creating multiple pores. Another reason was that the wrapped NaCl in the internal pore channels was dissolved and removed, subsequently forming the "leaving pores" [29]. From the specific surface area (SBET) distribution, it could be concluded that B-doping process largely increased the SBET of CSB-750 (822.23 m2/g) relative to that of CS-750 (486.15 m2/g). Such results might be ascribed to the gasses release (H2 and H2O) during boric acid thermal decomposition, which generated more pores and thereby enhanced the surface area. This hypothesis was further verified by 4.65-folds higher pore volume (1.21 cm3/g) and 2.23-times pore diameter (5.90 nm) for CSB-750 than CS-750 (0.26 cm3/g and 2.64 nm). Noting that, when increased carbonization temperature to 850 ℃ and 950 ℃, the BET had a decline, corresponded to CSB-850 (632.92 m2/g and 1.05 cm3/g) and CSB-950 (653.33 m2/g and 1.02 cm3/g). It was reported that high calcination temperature could cause the collapse of porous structure and then lower the pore volume and SBET [30]. In addition, it was rational that CSB-650 possessed small SBET (416.25 m2/g) and pore volume (0.61 cm3/g), possibly because low pyrolysis temperature was unfavorable for the formation of graphitized carbon skeleton. Overall, the large surface area and pore volume of CSB-750 contributed to the mass transfer and active site exposures, strongly supporting pollutant adsorption and catalytic oxidation.

Figs. 2d and e illustrated the Raman spectroscopy of all carbon materials. Obviously, there existed in two distinct peaks at 1350 cm–1 and 1580 cm–1, corresponding to the D band and G band, respectively. The D band stands for defective and disorder carbon and the G band belongs to sp2-hybridized graphitic carbon. The intensity ratio of D band to G band (ID/IG) can be used to evaluate the defect degree of carbonaceous materials. In comparison with the ID/IG of single S-doped CS-750 (0.9646) and sole B-doped CB-750 (0.9453), S,B-co-doped carbons (CSBs) exhibited the higher ID/IG values of 0.9670–1.0037. This phenomenon indicated that the substitution of partial C by B and S created more defective sites. After B element doping, the bond length of the newly emerged C-B was distinct with C—C and C—S bonds, which would reinforce the asymmetry of the electron distribution in the carbon network and hence modulated the geometric defects. Moreover, an increased preparation temperature would improve the defective degree, depicted by ID/IG values: CSB-650 (0.9670) < CSB-750 (0.9910) < CSB-850 (1.0037) ≈ CSB-950 (0.9981). As known, the chemical bonds were more easily cleaved and reconstructed at high temperature, forming more defective sites [31].

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was measured to analyze the surface functional groups of as-derived carbons. As illustrated in Fig. 2f, all catalysts showed strong absorption peaks at 1623 cm–1 and 3435 cm–1, which represented the stretching vibrations of C=O and -OH functional groups, respectively [23]. The weak peak at 1385 cm–1 was associated with the stretching vibration of C-S bond [32]. Except B-free catalyst CS-750, the other catalysts contained a relatively weaker absorption peak at 1126 cm–1, referring to the C-B/B-O signal peak [33]. Their low diffraction intensity resulted from the low proportion of B (0.56%−1.76%).

In order to further analyze the chemical compositions and elemental configurations, XPS measurement was implemented. The atomic percentages were listed in Table S2 (Supporting information). After B doping, the proportion of S reduced from 2.47% (CS-750) to 1.80% (CSB-750), implying a portion of S was replaced by B. In CSB-650, the B and S only accounted for 1.51% and 0.56%, respectively. This was because low heating temperature did not favor the incorporation of S and B into π-conjugated carbon framework. As anticipated, the S content manifested a downward trend as the calcination temperature rise from 750 ℃ to 850 ℃ and 950 ℃ (1.80% > 1.72% > 1.55%). The reason for this fact was ascribed to the decomposition of S-containing groups considering its instability at high temperature. Contrary to sulfur, the boron achieved a higher content at 850 ℃ or 950 ℃ rather than at 750 ℃, revealing the high thermal stability of B.

Fig. S2 (Supporting information) showed the S 2p XPS spectra of all samples. The two peaks at 163.5 eV and 164.6 eV were attributable to S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2 due to spin-orbit coupling of thiophene-sulfur (C-S-C). Another peak at 168.0 eV was derived from the oxidized sulfur (C-SOX-C). Evidently, the thiophene S content of CSBs was up to 77.51%–89.14%, and was far more than that of sole S-doped carbon CS-750 (50.21%) (Fig. 2g and Table S3 in Supporting information). It can be assumed that S,B-doping stimulates the formation of thiophene-sulfur instead of oxidized sulfur. Based on former reports, the thiophene-S containing lone-pair electrons could act as Lewis basic center to promote electron transfer to the electrophilic oxygen of the persulfate, leading to O—O bond cleavage and reactive oxygen species production [26]. Fig. 2h, Fig. S3 and Table S4 (Supporting information) depicted the B 1s high-resolution XPS spectrum and content of three boron species, which comprised of three components: BC3 (189.9 eV), BC2O (191.2 eV), and BCO2 (192.3 eV) [34]. The C 1s spectrum could be fitted into four parts: C–C/C=C (284.8 eV), C–OH/C–O–B (286.3 eV), C=O (287.7 eV) and O=C–O (289.4 eV) (Fig. S4 and Table S5 in Supporting information).

Integrating porous structures with various O- or S-containing groups, carbon materials universally possess good adsorption properties for organic contaminants. Thus, the adsorption experiments were performed within 210 min for adsorption-desorption equilibrium. As could be seen in Fig. S5a (Supporting information), the adsorptive removal of SMX by these samples were relatively low, with the values of only 0.6%−22.9%. Nevertheless, co-doping B into S-embedded carbon indeed enhanced the adsorptive properties, which was confirmed by the adsorption capacity orders: CSB-750 (22.9 mg/g) > CSB-850 (19.6 mg/g) > CSB-950 (17.6 mg/g) > CSB-650 (1.5 mg/g) > CB-750 (1.0 mg/g) ≈ CS-750 (0.6 mg/g). Boron atom with electron-deficient and low electronegativity (2.04 of XB < 2.55 of XC) could alter the electronic structure and surface chemistry of carbonaceous materials, affecting the adsorption nature [35]. In addition, the incorporated B can act as Lewis acid sites to bond organic molecule, as a result promoting the adsorption. The maximum adsorption capacity of CSB-750 (22.9 mg/g) may be related to its higher SBET (822.23 m2/g) and larger pore volume (1.21 cm3/g). Comparatively, for CSB-650, the low adsorption ability was presumably due to that the low carbonization temperature resulted in low SBET (416.25 m2/g) and pore volume (0.61 cm3/g). The adsorption process of CSB-750 could be better fitted by pseudo-second-order (R2 = 0.9819) instead of pseudo-first-order model (R2 = 0.9308), indicating the domination of chemical adsorption (Figs. S5b and c in Supporting information). Additionally, the Langmuir model (R2 = 0.9280) exhibited the higher correlation coefficient (R2) than Freundlich model (R2 = 0.8538), demonstrating monolayer adsorption was predominated (Figs. S5d and e in Supporting information).

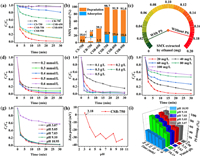

To validate the catalytic performances of as-prepared carbocatalysts, SMX removal was investigated by PS activation. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, a negligible concentration decline could be observed in the PS alone, suggesting that PS cannot oxidize SMX by itself. After PS addition, only 3.9%−18.6% SMX was removed for mono B- and S-doping catalyst (CB-750 or CS-750). By contrast, S and B co-doping promoted the reactivity remarkably. Amongst, the CSB-750 accounted for 98.7% removal of SMX within 30 min, which largely surpassed the adsorptive removal rate of 22.9% (Fig. 3b). The kobs was up to 0.1679 min–1, which showed 22.38- and 279.83-folds improvement over CS-750 (0.0075 min–1) and CB-750 (0.0006 min–1), respectively (Fig. S6 in Supporting information). The substantial improvement might benefit from the coupling effect of S,B-co-doping. As for sulfur, the large atomic radius (1.02 Å of S vs. 0.77 Å of C) can alter the bond length of adjacent C atom, then generating structural defects [36]. Besides, the embedded-S with high spin density can also create spin charge in carbon lattice [37]. B-doping can enable the Fermi energy level of carbon material to shift the guide band, which accelerates the electron transfer reaction on the surface of carbon material [21]. Therefore, S,B-co-doping can optimize the electronic structure, break the chemical inertness of carbon network, and create defective sites, as a result accelerating the oxidation process. Furthermore, in order to further verify whether the adsorbed SMX was degraded on the catalyst surface, SMX was extracted from the reacted catalyst with ethanol. As illustrated in Fig. 3c, the extracted amount of SMX in the adsorption process was 0.1783 mg. However, this value is only 0.0151 mg in the oxidation process, which was 91.5% smaller than that in the adsorption process. This result indicated that SMX adsorbed onto the catalyst could be effectively degraded.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) SMX degradation curve with different catalysts; (b) Adsorptive and oxidative removal of SMX; (c) Extracted SMX with ethanol from the used catalyst (detected at 30 min); SMX removal efficiency at different conditions: (d) PS dosage, (e) catalyst dosage, (f) SMX concentration and (g) initial solution pH; (h) Zeta potential of CSB-750 in various pH; (i) PS decomposition and final solution pH in different systems. Reaction conditions: [SMX] = 20 mg/L, [PS] = 0.5 mmol/L, [Catalyst] = 0.2 g/L, initial solution pH 5.05, unless specially highlighted in the figure. | |

In the case of CSB-650/PS system, a removal efficiency of 39.1% and 0.0147 min–1 were found, and they were below those of CSB-750 (Fig. 3b and Fig. S6). This could be explained that the low calcination temperature was unfavorable for the formation of graphitic carbon skeleton and the incorporation of B and S atoms into the carbon backbone, thereby lowering the number of active centers and catalytic performance. As steadily increased calcination temperature, the CSB-850 and CSB-950 exhibited inferiority (91.0%−91.9%; 0.0716–0.0753 min–1) as compared with CSB-750. Under high annealing temperature, the carbon nanomaterials were easy to be aggregation and pore structure collapse, inhibiting the exposure of active sites [27]. This reasoning agreed well with pore volume orders: CSB-750 (1.21 cm3/g) > CSB-850 (1.05 cm3/g) ≈ CSB-950 (1.02 cm3/g) (Table S1). Interestingly, in spite of different pyrolysis temperature, CSB-850 and CSB-950 showed the similar degradation behaviors. Such results might be due to their almost identical proportions of BC3+BC2O (27.07% vs. 26.65%) and thiophene-sulfur content (79.27% vs. 77.51%) (Tables S3 and S4). The phenomenon implied that BC3, BC2O, and thiophene S might be potential active sites. In general, the S,B-co-doped carbons prepared at a suitable temperature was effective in catalyzing persulfate, whose catalytic performance was comparable to those of many reported carbon- or carbon-metal-based catalysts (Table S6 in Supporting information).

It is well known that PS concentration affects the forming efficiency of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the direct catalytic oxidation. Thence the effect of PS dosage on SMX removal was investigated in Fig. 3d. When PS dosage increased from 0.2 mmol/L to 0.5 mmol/L, kobs was significantly reinforced from 0.0850 min–1 to 0.1679 min–1 (Fig. S7a in Supporting information). Correspondingly, the removal rate heightened from 83.5% to 98.7%. This promotion could be explained that more PS guaranteed full contact with catalyst, as a result enhancing the collision probability between them and generating more ROS. However, at PS = 0.6 mmol/L, the almost invariant removal efficiency (0.1360 min–1) was observed in comparison with that at PS = 0.5 mmol/L. This phenomenon might be due to the number of active sites on the catalyst surface limited the further PS activation. Therefore, the optimal PS dosage of 0.5 mmol/L was used in the following experiments.

The effect of different amount of CSB-750 on SMX degradation was illustrated in Fig. 3e. Apparently, an increased dosage of catalyst was in favor of SMX removal. With a small dosage of 0.1 g/L, only 48.0% of SMX was eliminated within 90 min and the kobs was 0.0470 min–1. The further rising dosage of 0.2 and 0.3 g/L consolidated SMX degradation to 98.7% and 99.0% within 30 min. Accordingly, the kobs was increased to 0.1679 min–1 and 0.2204 min–1, respectively (Fig. S7b in Supporting information). Under these conditions, more available active sites on carbon surface can effectively catalyze PS to generate ROS, leading to a positive contribution on SMX removal. However, when catalyst dosage continued increasing to 0.4–0.5 g/L, the degradation performance exhibited marginal improvement. This should be attributed to the limited amounts of PS, resulting in the saturation of active sites on carbon surface.

The influence of initial SMX concentration on the removal efficiency was also researched and displayed in Fig. 3f. As similar to the previous literature, accompanying the increase of pollutant concentration, both the removal rate and degradation rate decreased. At SMX concentration of 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 mg/L, the removal rate followed the orders of 98.7% > 89.8% > 73.8% > 52.9% > 49.2%. And the kobs were 0.1679 min–1, 0.0503 min–1, 0.0232 min–1, 0.0183 min–1, and 0.0100 min–1, respectively (Fig. S7c in Supporting information). This negative effect might be attributed to the following two factors. On one hand, the limited active sites and loss of active sites covered by more pollutant molecules, resulting in the inhibition of PS activation [38]. On the other hand, the inadequate PS dosage was also in charge of the low oxidation efficiency at high concentration of pollutant. Notably, at far exceeding actual wastewater concentration of 100 mg/L, the removal rate still reached 49.2%, demonstrating a great prospect of CSB-750 in practical application.

To estimate the influence of pH, the degradation experiments were carried out at varying solution pH of 3.07, 5.05, 7.03, 9.10 and 10.95. As shown in Fig. 3g, the removing efficiency was found to be almost insensitive to the initial pH of 3–9, and more than 98.7% of SMX was removed within 30 min. Comparatively, a severe degradation deterioration happened at the initial pH of 10.95, and only 43.7% SMX removal was obtained. The kobs value of 0.0161 min–1 was 10.43-times smaller than that at pH 5.05 (0.1679 min–1) (Fig. S7d in Supporting information). To gain clear insights into the inhibition effect at pH 10.95, the Zeta potential of CSB-750, pH variation, and PS decomposition rate were investigated. Firstly, the Zeta potential of CBS-750 was calculated to be 3.18 (Fig. 3h). That implied that the catalyst was mainly negatively charged at the aquatic solution pH > 3.18. In addition, given the pKa of 1.7 and 5.7, SMX dominated in negatively charged forms at initial pH > 5.7 [39]. Therefore, at pH 10.95, there existed in an electrostatic repulsion among CSB-750, negatively charged SMX and S2O82–, which would weaken their interaction and then lower PS activation catalyzed by CSB-750 [40]. The inhibited PS activation was confirmed by PS consumption orders of 41.7% (pH 10.95) < 83.5%−89.7% (pH 3–9) (Fig. 3i and Fig. S8a in Supporting information). With inefficient PS catalysis, the insufficient ROS would give rise to low SMX oxidation, which was in good agreement with Fig. 43.7% SMX removal at pH 10.95. As previously reported that, the production of hydrogen (H+) deriving from PS decomposition could reduce the pH (Eqs. 1–3) [41]. Therefore, the pH change during degradation was measured. As anticipated, the solution pH was merely decreased to 10.15 at initial pH 10.95. Reversely the final solution pH values were around 3.32 at initial pH 3–9 (Fig. S8b in Supporting information). Surprisingly, although this electrostatic repulsion among CSB-750, negatively charged SMX, and S2O82– still existed at initial pH 9.10, the corresponding removal efficiency was at a high level (98.2% and 0.1634 min–1). It was deduced that the electrostatic interaction was limited at this time, and PS adsorption and activation by CSB-750 was not interfered.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Quenching effect of MeOH and TBA (a), BQ (b) and L-histidine (c); (d) EPR spectra obtained with DMPO at different reaction conditions; (e) EPR spectra obtained with TEMP; (f) EPR signal detected with TEMP at different reaction time; (g) N2 and O2 purging experiment; (h) Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) analysis in different systems; (i) Effect of NaClO4 towards SMX degradation. Inset: kinetic rate constant (kobs) in presence of NaClO4. Reaction conditions: [SMX] = 20 mg/L, [PS] = 0.5 mmol/L, [CSB-750] = [CSB-750a] = 0.2 g/L, [CSB-750b] = 0.02 g/L, [DMPO] = [TEMP] = 100 mmol/L. | |

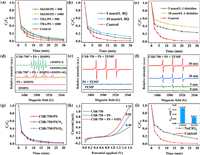

Generally, the main mechanisms in carbon-activated persulfate system are involved in radical pathways (SO4·− and ·OH) and nonradical pathways (1O2 and direct electron transfer) [42]. The chemical quenching experiments were utilized to discriminate the contribution of ROS in SMX degradation (Fig. 4). Herein, MeOH was chosen to quench both SO4·− and ·OH with reaction rate constant of 1.1 × 107 L mol–1 s–1 and 9.7 × 108 L mol–1 s–1, respectively [43]. While TBA was the scavenger of ·OH (k = 6 × 108 L mol–1 s–1), but not SO4·− (k = 4 × 105 L mol–1 s–1) [44]. As illustrated in Fig. 4a and Fig S9a (Supporting information), the addition of MeOH subtly suppressed SMX degradation. The kobs decreased from 0.1679 min–1 to 0.1547 min–1 and 0.1546 min–1, along with the increasing MeOH/PS ratio from 0 to 500 and 1000. Analogous results could be also observed after adding TBA with [TBA/PS] = 500 or 1000. These phenomena revealed that SO4·− and ·OH were both involved in CSB-750/PS/SMX system, but their contributions were marginal. The inhibition of SMX degradation by TBA was slightly higher than that by MeOH. This abnormal experimental phenomenon can be explained that TBA is more hydrophobic than MeOH due to the longer carbon chain. In this case, TBA was more prone to be adsorbed onto the catalyst surface than MeOH, resulting in more significant aggregation of catalyst and less available surface active sites. Thus TBA exhibited the stronger inhibitory effect than MeOH. As a representative scanvenger of superoxide anion, the addition of 10 mmol/L p-benzoquinone (BQ) caused 9.76% reduction in SMX concentration, implying the existence of O2·− (Fig. 4b) [45]. L-Histidine as a quencher of 1O2 was used to confirm the nonradical pathway (Fig. 4c and Fig. S9b in Supporting information) [46]. The addition of 5 mmol/L-histidine inhibited SMX removal from 98.7% to 77.6%, correspondingly the kobs reduction from 0.1679 min–1 to 0.0321 min–1. More detrimental effect was presented using 10 mmol/L-histidine, and the removal efficiency reduced to 63.5% and 0.0215 min–1. Such an inhibition demonstrated that 1O2 should be taken as the primary reactive specie. Likewise, the addition of other 1O2 scavengers (NaN3 and FFA) were also harmful to SMX removal and endowed 46.7%−68.3% reduction (Fig. S10 in Supporting information). These above results confirmed the generation of SO4·−, ·OH, O2·− and 1O2 in the course of PS activation by CSB-750. Again, this was supported by PS decomposition rates in different quenching systems (Text S4 and Fig. S11 in Supporting information).

Subsequently, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurements were used to further differentiate the ROS in the catalytic system. By employing DMPO (5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide), the generation of O2·−, SO4·− and ·OH were determined. O2·− was failed to be detected in spite of repeated attempts (Text S5 and Fig. S12 in Supporting information). As displayed in Fig. 4d, no EPR signal peaks could be observed in the sole PS system, which showed that PS can not produce ROS by its self-decomposition. As the addition of CSB-750, the expected signal peaks of DMPO-OH (αH = αN = 14.9 G) and DMPO-SO4 (αH = 9.6 G, αH = 1.48 G, αN = 0.78 G, and αN = 13.2 G) were absent [47]. Alternatively, a strong seven-line EPR signal with intensity ratio of 1:2:1:2:1:2:1 appeared, referring to the signal peak of DMPO-X [48]. In the pioneering reports, DMPO-SO4 and DMPO-OH were deemed to be unstable and easily oxidized into DMPO-X [49]. Also, To our knowledge, DMPO can be oxidized in aqueous solution by 1O2 into DMPO-X (k = 1.8 × 107 L mol−1 s–1) [50]. Thus, to mitigate this 1O2-induced DMPO-SO4 and DMPO-OH oxidation, the CSB-750 dosage was reduced from 0.2 g/L to 0.02 g/L aiming at diminishing 1O2 production. As shown in Fig. 4d, the signal peaks of DMPO-OH and DMPO-SO4 emerged. This is a straightforward evidence that the radicals (·OH and SO4·−) participated in the degradation process. Aiming at detecting 1O2, the spin trapping agent of TEMP (4‑hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine) was utilized. Fig. 4e depicted no EPR signals for catalyst or PS alone, but simultaneous addition of CSB-750 and PS produced a representative triple isointensity peak (1:1:1). This spectrum might derive from the adduct of TEMP with 1O2, namely TEMP-1O2 (αN = αN = αN = 16.9 G). Fig. 4f illustrated that the intensity of 1O2 signal in CSB-750/PS system could last more than 30 min, implying continuous generation of 1O2. These findings were consistent with the results of quenching experiments. As a whole, both radical and nonradical pathways contributed to SMX degradation, in which 1O2 exerted a primary contribution, while SO4·− and ·OH played a subordinate role.

Typically, in carbon-driven persulfate activation, the origins of 1O2 were mainly focused on three aspects: reorganization of O2·−, conversion of dissolved oxygen, and PS activation by structure defects [45,51]. To clarify the real origin of 1O2, more efforts have been input. Usually, O2·− does not oxidize organic contaminants directly, but reacts with H2O, ·OH, SO4·−, and hydrogen ion (H+) via self-recombination to generate 1O2 (Eqs. 4–7) [41]. On the basis of the quenching and PS utilization experiments, O2·− was present in the system. In addition, N2 and O2 purging experiments were conducted to evaluate whether the conversion of dissolved O2 to O2·−. From Fig. 4g, the trivial impact of N2 and O2 revealed that 1O2 did not stem from dissolved oxygen. In other respects, the structure defect can create dangling σ bond, then avoid the π-conjugated electron from being restricted by the edge carbon atom, as a result creating a delocalized electrons region [52]. This delocalized electrons from geometric defects can be migrated to PS, resulting in peroxy bond cleavage of PS and the formation of 1O2. The change of defect degree was characterized by Raman spectrum before and after activation. The orders of ID/IG values followed by 0.9738 (used CSB-750) < 0.9910 (raw CSB-750), which signified the consumption of defective sites during the catalysis (Fig. S13 in Supporting information). Hence, it was ascertained that 1O2 originated from the conversion of O2·− and direct PS activation by structure defects.

Apart from 1O2, the direct electron transfer is other plausible nonradical pathway in the realization of organic matter mineralization [53,54]. In the electron transfer process, the carbon materials act as electron channels to transfer two electrons from organics (electron donor) to PS (electron acceptor). The low electrochemical impedance and good conductivity of carbonaceous materials support receiving the electron from the aromatic pollutants. To assess the electron transfer process, Linear Scanning Voltammetry (LSV) was measured in different systems: only CSB-750, CSB-750/PS, and CSB-750/PS/SMX. The maximum oxidation currents were recorded at 1.6 V and generalized in Table S7 (Supporting information). As shown in Fig. 4h, the oxidation currents for CSB-750 and CSB-750/PS systems were 0.40 mA and 0.84 mA, respectively. However, when PS and SMX were simultaneously added, the electrochemical currents were improved by 1.36 times (1.14 mA) as compared to the CSB-750/PS system (0.84 mA). This case proved the occurrence of electron transfer process in CSB-750/PS/SMX system. In order to further certify the proposed point, quenching experiments using NaClO4 (10 mmol/L) as electron scavenger were carried out (Fig. 4i). Compared to the control, the addition of NaClO4 gave rise to moderate kobs reduction from 0.1679 min–1 to 0.0677 min–1. This was another strong evidence existing the electron transfer. Moreover, the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) for CS-750, CB-750, and CSB-750 as well as the open circuit potential (OCP) in the process of PS activation have been examined (Text S6 and Fig. S14 in Supporting information). The tested results show that a better electron transfer capacity for CSB-750 and the formation of metastable complex C-S2O82–* in the process of PS activation.

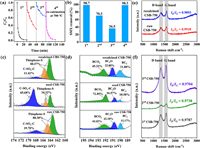

The stability test of CSB-750 was conducted through consecutive reaction cycles. The degradation performance dramatically declined after three cycles from 98.7% (1st) to 70.3% (2nd) and 36.5% (3rd) (Figs. 5a and b). This reduction might result from catalyst deactivation. Firstly, compared with the XPS spectra of fresh and used CSB-750, the proportion of thiophene S dropped from 80.30% to 34.32%, while oxidized sulfur (C-SOx-C) enhanced from 19.70% to 65.68% (Fig. 5c and Table S3). Likewise, the total amount of BC3 + BC2O had a reduction from 57.35% to 27.15% (Fig. 5d and Table S4). The above results indicated that thiophene S and BC3/BC2O were converted into C-SOx-C and BCO2 during PS activation process. Furthermore, after activation, the increased O content (5.30% to 12.37%) also supported the above-mentioned transformation on the side (Table S2). These findings provided direct proof that thiophene S, BC3 and BC2O were the active sites for PS activation. Similar results were also stated in other related literature [22,55].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. (a) Repeated SMX degradation and catalyst regeneration; (b) SMX removal rate for each cycle; S 2p (c) and B 1s (d) XPS spectra for raw CSB-750, used CSB-750 and recalcined CSB-750; (e, f) Raman spectrum of raw and recalcined CSB-750 and after each cycle. Reaction conditions: [SMX] = 20 mg/L, [PS] = 0.5 mmol/L, [CSB-750] = 0.2 g/L, initial solution pH 5.05. | |

Apart from the loss of the active groups, more elaborations were adopted to detect the defective degree variation of catalyst before and after oxidation (Figs. 5e and f). The defect degree of carbocatalysts decreased sequentially after each cycle, with ID/IG values of raw CSB-750 (0.9910) > 1st CSB-750 (0.9787) > 2nd CSB-750 (0.9738) > 3rd CSB-750 (0.9704). It should be pointed out that structural defects were the well-accepted sites in catalytic PS for 1O2 production [56]. Therefore, the decrease in defective degree after catalysis was responsible for the deactivation. In addition, the SBET orders of used CSB-750 (631.67 m2/g) < raw CSB-750 (822.23 m2/g) showed the catalyst coverage by intermediates/parent SMX, which was not conducive to the exposure of active sites, consequently leading to the catalyst deactivation (Table S1). Furthermore, the XPS and Raman spectra of CS-750 and CB-750 before and after reaction were tested. In Fig. S15 (Supporting information), the thiophene S content of CS-750 after reaction decreased from 49.79% to 39.87%. Similarly, the total BC3 + BC2O amount of CB-750 after reaction decreased from 6.80% to 3.48%. The variation of the defect degree before and after oxidation was also tested. The ID/IG values of CS-750 and CB-750 decreased from 0.9646 to 0.9430, 0.9453 to 0.9398, respectively. Therefore, thiophene S, BC3/BC2O, and structural defects were both proved to be the active sites in PS activation.

To be excited, thermal annealing (at 700 ℃ for 2 h under N2 atmosphere) could recover the catalytic activity of CSB-750. In this occasion, this value was 98.3% (0.1662 min–1) for the 4th cycle, and pretty close to 98.7% (0.1679 min–1) for the 1st run. By analyzing the XPS spectra of used and re-calcined CSB-750, the proportion of thiophene S and total BC3 + BC2O increased from 34.32% to 88.57%, and 27.15% to 54.68%, respectively (Figs. 5c and d). On the contrary, heat treatment reduced the content of C-SOx-C and BCO2 from 65.68% (used CSB-750) to 11.43% (re-calcined CSB-750), and 72.85% (used CSB-750) to 45.32% (re-calcined CSB-750), respectively. These might be attributed to the transformation of C-SOx-C to thiophene S and BCO2 to BC3/BC2O. As similar to the varying tendency of thiophene S and BC3/BC2O, the ID/IG value and SBET also became larger accordingly, as described by re-calcined CSB-750 (0.9893 and 696.59 m2/g) > used CSB-750 (0.9738 and 631.67 m2/g) (Fig. 5e and Table S1). Briefly speaking, this reversible conversion regarding thiophene S-oxide (C-SOx-C), BC3/BC2O-BCO2, structural defects, and SBET collaboratively contributed to the deactivation and regeneration of catalyst. Again, the thiophene S, BC3/BC2O, and structural defects were proved to be the active sites for PS activation.

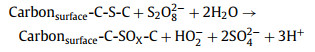

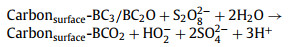

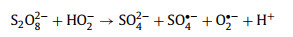

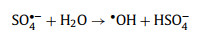

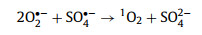

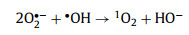

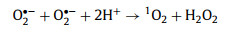

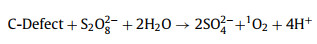

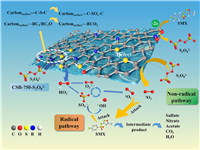

Coupled with the above results, the possible catalytic mechanism was proposed in Scheme 1. Firstly, boron containing a vacant p orbital acted as Lewis acid site to strengthen the PS adsorption onto carbon surface, forming the CSB-750-S2O82– complex (described in Texts S6 and S7, Figs. S14 and S16 in Supporting information) [23]. Thiophene S served as the Lewis basic site to transfer electrons to the electrophilic oxygen of the CSB-750-S2O82– complex, resulting in the breakage of the O—O bond into HO2– and SO42– (Eq. 1) [4]. Similar activation process might happen between BC3/BC2O and CSB-750-S2O82– (Eq. 2) [57]. A subsequent reaction HO2– with S2O82– generated SO4·− and O2·− (Eq. 3) [41]. One part of SO4·− reacted with H2O to form ·OH (Eq. 4) [58]. The resulting O2·− applied as the precursor to react with SO4·−, ·OH, and H+ via self-recombination, getting non-radical species 1O2 (Eqs. 5-7) [41]. In view of previous researches, the structure defects on carbonaceous materials could act as reactive sites and thus mediate PS to generate 1O2 (Eq. 8) [56]. Finally, the graphitized carbon as electron transfer channels to transfer two electrons from SMX to PS, namely direct electron transfer pathway (Eq. 9) [43]. These reactive species attacked SMX to generate intermediates, then a further oxidization formed sulfate, nitrate, acetate, CO2 and H2O. To sum up, both thiophene S, BC3 and BC2O as active sites catalyze CSB-750-S2O82– complex to produce SO4·−, ·OH and O2·−, in which the transformation of O2·− produces partial 1O2; an additional origin of 1O2 assigns to the direct catalysis of persufate by structural defects. Reactive oxygen species, like SO4·−, ·OH, O2·− and 1O2 were both involved in CSB-750/PS/SMX system. 1O2 dominated SMX degradation. SO4·−, ·OH, and electron transfer played the minor role.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

|

(10) |

|

(11) |

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Mechanism of PS activation on CSB-750. | |

As for boron, benefiting from the lower electronegativity than carbon and electron-deficient property (a vacant p obital), the incorporation of B can change the charge density and electronic structure of carbon network. Specially, sulfur possesses a larger atomic radius than carbon, which can create structural defects in carbon lattice. Theoretically, coupling of S and B can not only modulate the electronic characteristics by tailoring spin and charge density, but also fabricate structural defect active centers. Furthermore, the formed B- or S-containing functionalities in the carbon matrix, including thiophene-S, BC3, and BC2O, are the potential reactive sites in PS activation. As shown in Table S8 (Supporting information), the introduction of S and B not only bring multiple active functional groups (thiophene S, BC3/BC2O), but also increase the defect sites and specific surface area, as certified by CSB-750 (0.9910 of ID/IG, 822.23 m2/g) > CS-750 (0.9646, 486.15 m2/g) and CB-750 (0.9453, 563.82 m2/g). One concludes that the coupling of S and B is a plausible strategy to enhance the catalysis.

Fig. S17 (Supporting information) exhibited the effect of various water backgrounds, including Cl–, H2PO4–, SO42–, NO3–, and humic acid (HA) towards SMX degradation in CSB-750-activated PS system. In order to exclude the indirect influence of pH change imposed by the addition of these components, the initial solution pH was analyzed and listed in Table S9 (Supporting information). Except for CO32– (initial pH of 10.98), all the pH values (4.73–8.73) were lower than 11 (causing substantial inhibition effect), ruling out the effect of pH. As depicted in Fig. S17a, the addition of Cl–, H2PO4–, SO42–, and NO3– brought about slight inhibition on degradation efficiency. Compared with the control (0.1679 min–1), the kobs reduced to 0.1591 min–1 (Cl–), 0.1329 min–1 (H2PO4–), 0.1519 min–1 (SO42–), and 0.1352 min–1 (NO3–) (Fig. S17b). According to related document, four anions could consume free radicals (·OH and SO4·−) to form new radical species, for instance Cl·− (2.4 V), Cl2·− (2.0 V), HOCl·− (1.48 V), and NO3·− (2.0–2.2 V) (Text S8 and Eqs. S1-S8 in Supporting information) [59]. These newly emerged radical substances commonly possess less oxidative ability relative to ·OH (1.8–2.7 V) and SO4·− (2.5–3.1 V), consequently undermining SMX degradation. The subtle influence by these anions were further revealed that radical pathway was involved, but exerted a minor contribution. In contrast, the presence of HA caused a predictable degradation inhibition (98.7% to 84.5%; 0.1679 min–1 to 0.0789 min–1). There were two factors accounting for this situation: (1) HA as a representative organic matter can capture radicals, leading to low ROS utilization for SMX oxidation, and (2) the attached HA on catalyst surface can cover the catalytic reaction sites, resulting in the loss of active sites and low oxidation efficiency [60].

However, a great inhibition effect occurred upon the addition of CO32– and HCO3–. With this regard, the removing efficiency declined from 98.7% to 55.2% for CO32– (0.0355 min–1) and 72.6% for HCO3– (0.0605 min–1) (Figs. S17c and d). The reasons behind the severe inhibition were investigated in detail here. As far as we know, CO32– can act as a typical scavenger of superoxide radicals (O2·–), which works as the precursor of singlet oxygen (1O2) (Eqs. 10 and 11) [45]. It could be presumed that CO32– induced inhibition effect was related to the decreased content of 1O2 in the reaction system. This hypothesis was confirmed by quenching and in-situ EPR analysis. One was clearly discovered that these triplet signals almost became half after adding CO32– (Fig. S17e), detected at 5 and 10 min). In addition, considering the initial pH of CO32– added system was 10.98, which was close to the pH (10.95) that could suppress SMX degradation. Thus, to be exclusive of pH interference, the extra degradation experiment was performed at initial pH of 8.98. As shown in Fig. S17c, the removal performance at pH 8.98 (80.9% and 0.0646 min–1) was better than that at pH 11 (55.2% and 0.0355 min–1) (Fig. S17d), indicating strong basic surrounding (pH 11) rendered an adverse role for SMX degradation. Overall, the CO32–-induced inhibition effect was as a result of the cooperation of pH and quenching O2·–.

To monitor the real water matrix, the degradation experiments were exploited using tap water (collected from Dongguan University of Technology), lake water (obtained from Dongguan Pine Lake misty rain-SSL), and diluted landfill leachate (Figs. S17f and g). SMX was added to the diluted landfill leachate to get 0.2 mg/L and 0.5 mg/L solution. The concentration of SMX in tap and lake water were both 20 mg/L. In comparison with the control experiment (deionized water), a certain degree of inhibition indeed appeared in the landfill leachate. But there still remained 62.6%−69.7% removal of SMX at the concentration of 0.2–0.5 mg/L. In particular, SMX removal rate from tap and lake water was as high as 94.3% and 92.3%, respectively. These above results witnessed the excellent prospect of CSB-750 in actual wastewater remediation.

Besides SMX, the degradation behaviors of other contaminants, for instance bisphenol A, ciprofloxacin, rhodamine B, and sulfamonomethoxine, were also investigated. As shown in Fig. S17h, quite swift removal (100%) could be found for rhodamine B and bisphenol A within 2 min. Within 30 min, the removal rate of ciprofloxacin and sulfamonomethoxine attained 85% and 91%, respectively. In addition, it was found that CSB-750 showed excellent activation effect on PMS (86.5% removal), but could not efficiently catalyze H2O2 to degrade SMX (Fig. S17i). These results indicate that the CSB-750 is a promising catalyst in removing organic contaminants.

The mineralization degree was investigated by total organic carbon (TOC) analysis (Fig. S18 in Supporting information). The TOC removal rate was up to 81.4% within 30 min, indicating an efficient mineralization into non-hazardous CO2 and H2O. To figure out the degradation pathways, the degradation intermediates were measured by liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometer (LC-MS). Tables S10 and S11 (Supporting information) listed the molecular structure of degradation intermediates and the related fragments according to m/z values and previous reports. The MS and MS2 spectrum were illustrated in Fig. S19 (Supporting information). A total of ten intermediates were identified, and nine possible degradation pathways (A-I) were put forward (Fig. S20 in Supporting information).

In pathway A, an electrophilic addition between ·OH and electron-rich aniline resulted in hydroxylation product P1 (m/z = 268.03967 [M−H]–) [61]. For pathway B, it could be involved in the C-S bond cleavage and follow-up oxidation by SO4·−, ·OH or 1O2 to get intermediate P2 (m/z = 108.04432 [M + H]+) [62]. In pathway C, 1O2 attacked the amino group (-NH2) on the benzene ring to form hydroxylamine-substitutional intermediate P3 (m/z = 268.03967 [M−H]–). Subsequently, the -NH—OH unit could be further oxidized by 1O2 to produce the -nitroso group, simultaneously accompanying the production of intermediate P4 (m/z = 266.02365 [M−H]–) (pathway D) [63]. As similar to pathway B, the nitrosobenzene P5 (m/z = 108.04432 [M + H]+) was formed by the C–S bond cleavage between benzene ring and sulfone (pathway E) [63]. In pathway F, the C–S bond cleavage and follow-up hydroxylation reaction in SMX generated sulfamic acid intermediate P6 (m/z = 176.99721 [M−H]–) [64]. The intermediate P6 endured one-step hydrolysis reaction with S–N bond breakage, resulting in sulfuric acid P7 (m/z = 96.95994 [M−H]–) and aminated-isoxazole intermediate P9 (m/z = 99.05549 [M + H]+), as illustrated in pathway G and G-2 [65]. The similar hydrolysis process also happened in pathway H, in return achieving sulfonic acid P8 (m/z = 156.01216 [M−H]–) and P9 [2]. For pathway I, the intermediate P10 (m/z = 156.01054 [M + H]+) was as a result of dehydrogenation and isomerisation of P8 [66]. The intermediates obtained from the various pathways underwent further oxidation to produce sulfate (m/z = 96.95994 [M−H]–), nitrate (m/z = 61.98828 [M−H]–), acetate (m/z = 59.01383 [M−H]–), CO2 and H2O (m/z = 60.99306 [M−H]–) (detected in the acid form).

Toxicity evaluation software was used to simulate the toxicity of degradation intermediates with the aid of quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) mathematical model [67]. The evaluation variables comprised of the acute toxicity of the half-lethal dose (LD50) (96 h) oral rat, developmental toxicity, and mutagenicity. These calculated results were provided in Fig. S21 and Table S12 (Supporting information). Although the predicted acute toxicity value of degradation intermediates (383–4279 mg/kg) were lower than that of SMX (7206 mg/kg), the LD50 of most intermediates were still within the low-toxic (200–2000 mg/kg) or nontoxic (more than 2000 mg/kg) criteria (Fig. S21a). Thus, these formed intermediates would not harm the environment. Distinctive from the acute toxicity, the developmental toxicity presented a downward trend, as certified by the lower toxicity value of intermediates (0.36–0.90, exclusive of P2) than that of parent SMX (0.91) (Fig. S21b). Even the intermediates P5, P7, P9 and P10 were predicted to be developmentally nontoxic. Seemingly, the mutagenicity of partial intermediates (P5 and P9) became slightly higher, but most intermediates (P1, P3, P4, P6 and P7) were not mutagenic (Fig. S21c). The above calculation results revealed that the toxicity still existed in a few intermediates after catalytic oxidation. It is necessary to prolong the reaction time to realize full mineralization of SMX into CO2 and H2O as much as possible.

The toxic effect of the CSB-750/PS system on Chlorella were also evaluated (Figs. S21d and S22, Text S9 and Table S13 in Supporting information). In the counterpart group T2 containing pure SMX solution, the growth inhibition percentage of Chlorella was as high as 83.1% after incubation for 96 h. While the inhibition proportion decreased to 8.9% in the experimental group T3, which was cultivated by the degraded SMX solution. This case demonstrates that CSB-750/PS system can reduce the SMX toxicity and exhibited potential application in contaminant detoxification.

In summary, S,B-co-doped carbon materials were successfully synthesized using one-step pyrolysis with sodium lignosulfonate, boric acid, and sodium chloride. The pseudo-second-order and Langmuir models fitted well for the adsorption process. The as-prepared CSB-750 exhibited superior activity in activating PS for SMX degradation. 98.7% removal and 81.4% mineralization could be obtained within 30 min. The rate constant (kobs) was up to 0.1679 min–1, corresponding to 22.38- and 279.83-folders higher than that of solo S-doping CS-750 (0.0075 min–1) and single B-doping CB-750 (0.0006 min–1), respectively. The CSB-750/PS system manifested excellent adaptability over a wide pH range of 3–9. Thiophene sulfur, BC3, BC2O, and structural defects were determined to be the reactive sites in activating PS. Radical and nonradical pathways were both involved in CSB-750/PS/SMX system, in which 1O2 dominated the degradation, SO4·−/·OH/direct electron transfer exerted the minor contribution, and O2·− acted as the precursor for the production of partial 1O2. Depending on the reaction intermediates, nine possible degradation pathways were proposed and the toxicity of the degradation system presented a certain degree of decline. Furthermore, other pollutants, such as bisphenol A, ciprofloxacin, rhodamine B, and sulfamonomethoxine, could also be degraded effectively by CSB-750/PS system. These findings demonstrated that S and B co-doping is indeed a feasible and efficacious approach to enhance the catalysis.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis study was financially supported by the GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Nos. 2019A1515110649, 2020A1515110271, 2019A1515110244), the National Natural, Science Fund of China (No. 51908127), the Guangdong Province Universities and Colleges Pearl River Scholar Funded Scheme (2017), the Research Team in Dongguan University of Technology (No. TDYB2019013).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.107755.

| [1] |

Y. Gao, Q. Wang, G. Ji, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 429 (2022) 132387. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.132387 |

| [2] |

S. Wang, L. Xu, J. Wang, Chem. Eng. J. 375 (2019) 122041. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.122041 |

| [3] |

K. Zhang, X. Min, T. Zhang, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 413 (2021) 125294. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125294 |

| [4] |

W. Huang, S. Xiao, H. Zhong, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 418 (2021) 129297. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.129297 |

| [5] |

J. Xu, J. Song, Y. Min, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 3113-3118. |

| [6] |

J. Yu, H. Feng, L. Tang, et al., Prog. Mater. Sci. 111 (2020) 100654. DOI:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100654 |

| [7] |

Y. Zhao, B. Huang, J. Jiang, et al., Chemosphere 244 (2020) 125577. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125577 |

| [8] |

A. Jawad, K. Zhan, H. Wang, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 54 (2020) 2476-2488. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.9b04696 |

| [9] |

W. Ren, L. Xiong, G. Nie, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 54 (2020) 1267-1275. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.9b06208 |

| [10] |

R. Paul, F. Du, L. Dai, et al., Adv. Mater. 31 (2019) 1805598. DOI:10.1002/adma.201805598 |

| [11] |

T. Zharig, T. Asefa, Adv. Mater. 31 (2019) 1804394. DOI:10.1002/adma.201804394 |

| [12] |

C. Hung, C. Chen, C. Huang, et al., J. Clean. Prod. 336 (2022) 130448. DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130448 |

| [13] |

Y. Liu, W. Miao, X. Fang, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 380 (2020) 122584. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.122584 |

| [14] |

C. Wang, J. Kang, H. Sun, et al., Carbon 102 (2016) 279-287. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2016.02.048 |

| [15] |

P. Sun, H. Liu, M. Feng, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 251 (2019) 335-345. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.03.085 |

| [16] |

S. Liu, Z. Zhang, F. Huang, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 286 (2021) 119921. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2021.119921 |

| [17] |

Y. Guo, Z. Zeng, Y. Li, et al., Catal. Today 307 (2018) 12-19. DOI:10.1016/j.cattod.2017.05.080 |

| [18] |

W. Sun, K. Pang, F. Ye, et al., Sep. Purif. Technol. 279 (2021) 119723. DOI:10.1016/j.seppur.2021.119723 |

| [19] |

X. Chen, X. Duan, W. Oh, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 253 (2019) 419-432. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.04.018 |

| [20] |

Y. Zheng, Y. Jiao, L. Ge, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52 (2013) 3110-3116. DOI:10.1002/anie.201209548 |

| [21] |

S. Yu, W. Zheng, Nanoscale 2 (2010) 1069-1082. DOI:10.1039/c0nr00002g |

| [22] |

C. Nie, Z. Dai, W. Liu, et al., Environ. Sci. Nano 7 (2020) 1899-1911. DOI:10.1039/D0EN00347F |

| [23] |

B. Liu, W. Guo, H. Wang, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 396 (2020) 125119. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.125119 |

| [24] |

Y. Wang, M. Liu, X. Zhao, et al., Carbon 135 (2018) 238-247. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2018.01.106 |

| [25] |

X. Duan, K. O'Donnell, H. Sun, et al., Small 11 (2015) 3036-3044. DOI:10.1002/smll.201403715 |

| [26] |

Y. Guo, Z. Zeng, Y. Li, et al., Sep. Purif. Technol. 179 (2017) 257-264. DOI:10.1016/j.seppur.2017.02.006 |

| [27] |

S. Liu, C. Lai, B. Li, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 384 (2020) 123304. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.123304 |

| [28] |

Y. Gao, T. Li, Y. Zhu, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 393 (2020) 6844. |

| [29] |

T. Li, H. Jin, Z. Liang, et al., Nanoscale 10 (2018) 6844-6849. DOI:10.1039/C8NR01556B |

| [30] |

D. Ding, S. Yang, X. Qian, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 263 (2020) 118348. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118348 |

| [31] |

S. Indrawirawan, H. Sun, X. Duan, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 3 (2015) 3432-3440. DOI:10.1039/C4TA05940A |

| [32] |

V. Thirumal, A. Pandurangan, R. Jayavel, et al., Synth. Met. 220 (2016) 524-532. DOI:10.1016/j.synthmet.2016.07.011 |

| [33] |

J. Li, W. Qin, J. Xie, et al., Nano Energy 53 (2018) 415-424. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.08.075 |

| [34] |

X. Yu, P. Han, Z. Wei, et al., Joule 2 (2018) 1610-1622. DOI:10.1016/j.joule.2018.06.007 |

| [35] |

Y. Zhao, L. Yang, S. Chen, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 1201-1204. DOI:10.1021/ja310566z |

| [36] |

X. Duan, H. Sun, S. Wang, Accounts Chem. Res. 51 (2018) 678-687. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00535 |

| [37] |

X. Huo, P. Zhou, J. Zhang, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 391 (2020) 122055. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122055 |

| [38] |

N. Liu, L. Zhang, Y. Xue, et al., Sep. Purif. Technol. 184 (2017) 213-219. DOI:10.1016/j.seppur.2017.04.045 |

| [39] |

B. Xu, F. Liu, P.C. Brookes, et al., Mar. Pollut. Bull. 131 (2018) 191-196. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.04.027 |

| [40] |

W. Ren, G. Nie, P. Zhou, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 54 (2020) 6438-6447. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.0c01161 |

| [41] |

Y. Qi, B. Ge, Y. Zhang, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 399 (2020) 123039. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123039 |

| [42] |

H. Qiu, P. Guo, L. Yuan, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 2614-2618. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.08.014 |

| [43] |

L. Tang, Y. Liu, J. Wang, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 231 (2018) 1-10. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.02.059 |

| [44] |

Y. Chen, Y. Lin, S.H. Ho, et al., Bioresour. Technol. 259 (2018) 104-110. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2018.02.094 |

| [45] |

X. Cheng, H. Guo, Y. Zhang, et al., Water Res. 113 (2017) 80-88. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2017.02.016 |

| [46] |

S.Y. Egorov, E.G. Kurella, A.A. Boldyrev, et al., IUBMB Life 41 (1997) 684-697. |

| [47] |

H.E. Gsponer, C.M. Previtali, N.A. García, Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 16 (1987) 23-37. |

| [48] |

L.E. J, Z.J. L, V.F. A, Org. Biomol. Chem. 3 (2005) 3220-3227. DOI:10.1039/b507530k |

| [49] |

J. Hou, J. Lin, H. Fu, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 389 (2020) 124344. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.124344 |

| [50] |

C. Liu, L. Chen, D. Ding, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 254 (2019) 312-320. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.05.014 |

| [51] |

J. Lee, S. Hong, Y. Mackeyev, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 45 (2011) 10598-10604. DOI:10.1021/es2029944 |

| [52] |

D. Xue, H. Xia, W. Yan, et al., Nano-Micro Lett. 13 (2021) 5-27. DOI:10.1007/s40820-020-00538-7 |

| [53] |

J. Wang, H. Guo, Y. Liu, et al., Appl. Surf. Sci. 507 (2020) 145097. DOI:10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.145097 |

| [54] |

W. Ren, C. Cheng, P. Shao, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 56 (2022) 78-97. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.1c05374 |

| [55] |

H. Liu, P. Sun, M. Feng, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 187 (2016) 1-10. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.01.036 |

| [56] |

X. Cheng, H. Guo, Y. Zhang, et al., Water Res. 157 (2019) 406-414. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2019.03.096 |

| [57] |

S. Zhu, X. Huang, F. Ma, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 52 (2018) 8649-8658. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.8b01817 |

| [58] |

Y. Long, S. Li, Y. Su, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 404 (2021) 126499. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.126499 |

| [59] |

J. Wang, S. Wang, Chem. Eng. J. 411 (2021) 128392. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.128392 |

| [60] |

X. Zhang, Z. Ding, J. Yang, et al., Environ. Chem. Lett. 16 (2018) 1069-1075. DOI:10.1007/s10311-018-0721-z |

| [61] |

Y. Bao, W. Oh, T.T. Lim, et al., Water Res. 151 (2019) 64-74. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2018.12.007 |

| [62] |

W. Zhu, Z. Li, C. He, et al., J. Alloy. Compd. 754 (2018) 153-162. DOI:10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.04.286 |

| [63] |

J. Niu, L. Zhang, Y. Li, et al., J. Environ. Sci. 25 (2013) 1098-1106. DOI:10.1016/S1001-0742(12)60167-3 |

| [64] |

S. Tian, L. Wang, Y. Liu, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 53 (2019) 5282-5291. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.9b00180 |

| [65] |

Y. Shang, X. Xu, Q. Yue, et al., Environ. Sci. Nano 7 (2020) 1444-1453. DOI:10.1039/D0EN00050G |

| [66] |

M. Pu, J. Niu, M. Brusseau, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 394 (2020) 125044. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.125044 |

| [67] |

Z. Yang, X. Xia, L. Shao, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 410 (2021) 128454. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.128454 |

2023, Vol. 34

2023, Vol. 34