b Technology Innovation Center for Land Spatial Eco-Restoration in Metropolitan Area, Ministry of Natural Resources, Shanghai 200062, China;

c Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Biotransformation of Organic Solid Waste, Shanghai 200241, China

Oxalic acid (H2C2O4) is an important dicarboxylic acid in atmosphere and is a common component of fog [1], tropospheric aerosols [2], precipitation [1], surface water and soil solutions [3]. Oxalic acid is not only derived from automobile exhaust, fossil combustion, biomass combustion and other incomplete combustion [4,5], but is a common product of photochemical oxidation reaction of many hydrocarbons [6,7]. Their concentrations in the atmosphere range from 10 ng/m3 in remote areas to hundreds or even more than 1000 ng/m3 in urban areas [8-10]. Besides, oxalic acid in soil mainly originates from roots secretion [11], plant residues and microbial metabolites [12], and its concentration is usually in the range of 0–50 µmol/L in soil [13]. In aqueous and atmospheric environment, oxalic acid is often chelated with iron to form photosensitive complexes [14], namely Fe(Ⅲ)-oxalate. Since the 1950s, a large number of studies have found that upon exposure to sunlight, aqueous Fe(Ⅲ)-oxalate complexes would undergo a rapid photochemical redox process [15-20].

Initially, the photochemistry of ferrioxalate has gained increasing attention due to its high solubility, high molar absorption coefficient and high reaction quantum yield. The quantum yield of Fe(Ⅱ) (ΦFe(Ⅱ)) is insensitivity to temperature, concentration, and light intensity [19,21], so that Fe(Ⅲ)-oxalate is known as the most widely accepted standard actinometer [22]. A pioneering work by Parker measured the ΦFe(Ⅱ) using ferrioxalate as a chemical radiometer [18]. Now the ΦFe(Ⅱ) is a known parameter at a specific wavelength range, for instance, 1.25–0.9 for ferrioxalate in the wavelength range of 250–500 nm [22]. Considering the high sensitivity and precision, wide wavelength responsiveness, stability of photolyte and photolysis products [18,19,23,24], ferrioxalate actinometer has been recommended by the International Union for Pure and Applied Chemistry as an actinometry used in liquid phase [25,26].

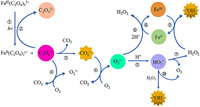

More than an actinometer, the ferrioxalate is known as a prevalent photoactive compound in atmospheric photochemistry and water treatment [27-29]. The photochemical redox reaction of ferrioxalate is an important source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [30,31], such as carbon dioxide anion radicals (CO2•−), superoxide radical anions (O2•−), hydroperoxyl radical (HO2•) and hydroxyl radical (•OH) (Fig. 1). The photochemical reaction of ferrioxalate could represent a vital source of H2O2 in the atmospheric liquid phase, which plays a critical role in atmospheric chemistry, such as the oxidation of SO2 to H2SO4 [32,33]. The photolysis process of ferrioxalate can promote the dissolution of Fe(Ⅲ) [34], and its decarboxylation process is an important mechanism of carbon cycle in natural waters. Besides, the production and consumption of ROS may also affect the redox process of some environmental elements, such as sulfur (S) [35], arsenic (As) [36], chromium (Cr) [37], and the decomposition and transformation of natural organic matter and man-made pollutants.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. The redox cycling of iron and associated ROS generation in the photolysis of Fe(Ⅲ)-oxalate. | |

Photo-Fenton assisted by Fe(Ⅲ)-oxalate has been developed as a new advanced oxidation processes. The strong oxidizing species (•OH) generated in this process can effectively degrade most refractory organic compounds [38-41]. The addition of ferrioxalate complex [42-46] can promote the photo-Fenton reaction at neutral pH, and avoid acidification and precipitation of iron hydroxide in traditional Fenton reaction [47,48]. It shows strong application potential in solar energy utilization, stabilization of the presence of iron in the solution during the sewage treatment, and mineralization of refractory organic pollutants [49-51]. Some examples of photo-ferrioxalate system in the treatment of organic pollutants in actual wastewater are summarized in Table S1 (Supporting information).

The wealthy photochemical properties of ferrioxalate complexes have been the focus of several ultrafast spectroscopy studies, including pump/probe transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy such as flash photolysis, time-resolved X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), femtosecond infrared (IR) absorption spectroscopy and ultrafast photoelectron spectroscopy (PES). The intermediate and stable products of the photolyzed ferrioxalate are well known, but there are some controversies yet about the initial photolysis of ferrioxalate at molecular level.

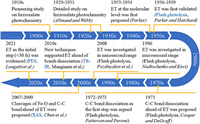

Therefore, in order to facilitate readers to better understand this old story, we have summarized the photochemical studies of ferrioxalate over the past century into a chronicle (Fig. 2). The first detailed study of the photochemical activity of ferrioxalate can be traced back to 1929 [16]. Later, Parker [52] first proposed that the initial step after photoexcitation is intramolecular electron transfer (ET), and introduced flash photolysis to confirm their view. This idea was later denied by DeGraff and Cooper [53] in 1971, who inferred that the dissociation of the C—C bond on the oxalate ligand would occur prior to ET. A year later, an experimental work using flash photolysis by Patterson and Perone [54] agreed with Cooper et al. In 1996, Nadtochenko and Kiwi [55] confirmed the ET mechanism by flash photolysis in the microsecond range, and suggested that a new ultrafast spectroscopy should be introduced. Therefore, in 2007, Chen et al. [24] introduced XAS into this system and proposed that the dissociation of the Fe–O bond is the first step in the photolysis of ferrioxalate. In 2008, Pozdnyakov et al. [56] commented on the work by Chen et al. A review by Pozdnyakov et al. [57] concluded that the main photochemical processes of Fe(Ⅲ) complexes with aliphatic (poly)carboxylic acids include ET and the formation of Fe(Ⅱ), which is further explained in another article [58]. Since then, both XAS and time-resolved infrared spectroscopy (TR-IR) investigations have been carried out to confirm the initial ET mechanism and further define the time range of ET occurrence. In 2018, Chen and Browne [59] reviewed the transient reduction of iron centers and the oxidative degradation of organic ligands in the photochemical reaction of ferrioxalate, which also supported the classical statement of ET. Recently, Longetti et al. [60] used a new method, PES, for the first time, and proposed that ET occurs in the range of less than 30 fs. However, despite advances in both fundamental research and applications, there is no consensus on the molecular-level mechanism, so the story remains unfinished.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. A chronicle of advances in the photochemistry of ferrioxalate at molecular level over the past century. | |

Despite the growing interest in the primary events of the ferrioxalate in the past, to our best knowledge, no reviews have been published so far that focus on the controversy about the molecular-level photolysis mechanism of ferrioxalate. Therefore, this review comprehensively discusses the mechanism and potential of the photochemical reaction of ferrioxalate. Also, more concerns are expressed about the behavior trajectory of ferrioxalate complexes under photoexcitation, including the overall reaction of ferrioxalate and the molecular level. Based on chronological order, the different TA spectroscopic methods used by different research groups are classified, which highlights the current controversy of ET and dissociation mechanism of ferrioxalate. Finally, we propose further prospects about the reaction mechanism of ferrioxalate as well as its application.

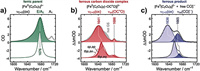

2. Primary photochemical processes of ferrioxalateAlthough the general photochemical processes and their photoproducts are widely accepted (see Text S1 in Supporting information for a brief review of previously reported general photochemical reaction mechanisms for ferrioxalate), its early chapters of this old story (the primary step of the photoreaction) remains as an unsolved mystery. So far, various methods have been employed to study the photoreaction of ferrioxalate in order to explain its redox mechanisms, especially TA spectroscopic [24,53-55,61]. The photochemical mechanisms proposed previously for the photolysis of ferrioxalate can be roughly divided into "prompt" and "delayed" ET. Fig. S3 (Supporting information) illustrates the main processes of intramolecular ET and bond dissociation in ferrioxalate.

The essential difference between these two most widely discussed mechanisms lies in the chronological sequence of one-electron reductions in iron center. The former photoexcitation results in one-electron ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT), which leads to instantaneous reduction of Fe(Ⅲ) and oxidative degradation of oxalate ligands [59,62-65]. In the latter case, the dissociation of C—C bond happens before ET, thereby producing a ferric intermediate with a double radical property in the ligand center [54,66]. In addition, electron photodissociation, and photoinduced spin crossover may be should also be considered. It cannot be neglected that the electrons in the ferrioxalate can charge out into the solution, and the complex also have spin crossover that may affect the reaction process.

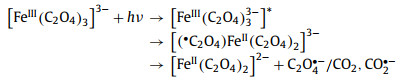

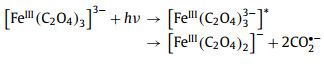

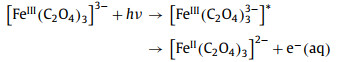

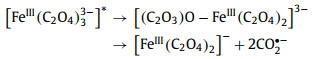

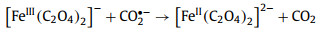

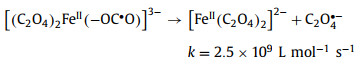

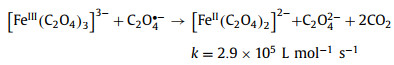

2.1. Intramolecular ETThis mechanism was first proposed by Parker [52] in 1954, indicating that intramolecular ET is the major event after light excitation. The electrons in the ferrioxalate molecule are transferred immediately from oxalate ligand to iron center under light excitation, thereby rendering the reduction of Fe(Ⅲ). The reaction mechanism within 100 ps is described in Eq. 1.

|

(1) |

The metastable [(•C2O4)FeⅡ(C2O4)2]3− is generated after an electron in the oxalate ligand moving into the iron center. Then, the key active intermediates C2O4•− or CO2•− are produced after the ligand dissociation. The photoreduction may also alter the molecular structure of ferrioxalate. The length of Fe(Ⅱ)–O bond is generally 0.1–0.2 Å longer than the length of Fe(Ⅲ)–O bond in the same iron complex [67,68], while the relocation and reallocation of an electron between iron metal and oxalate ligand would disrupt the D3 symmetry of the parent molecule [69].

2.2. Dissociation of bonds in ferrioxalateIn 1971, Cooper et al. conducted a more detailed kinetic study using 340–500 nm irradiation, and concluded from the observed transient spectra that the primary process of ferrioxalate photolysis is not intramolecular ET [53,69]. Firstly, a C–C bond breaks before the ET, and generates a ligand-centered ferric intermediate with biradical character (Eq. 2). Secondly, the dissociation of Fe–O bond also needs to be considered. The valence state of iron remains at +3 (Eq. 3). In this mechanism, the transient (FeⅢ(C2O4)2−) is generated within 5 ps, and its decay life is in the range of nanosecond. In short, the primary photodissociation of ferrioxalate includes the dissociation of the Fe–O bond between the iron center and oxalate ligand, and the cleavage of the C—C bond in the oxalate ligand.

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

In conclusion, the initial redox reaction of Fe(Ⅲ)-oxalate under light may involve ET, dissociation, or both. In both mechanisms, either C2O4•−or CO2•− anion radicals may be generated. These radicals will further react with FeⅢ(C2O4)33− molecules to form an additional Fe(Ⅱ) product, resulting in total quantum yields larger than one in the photochemical reaction of ferrioxalate.

2.3. Electron photodissociationPrevious studies [24,68,69] have identified visible absorption bands in the regions of 500–800 nm and 380–500 nm in TA spectrum, among which the absorption band at 500–800 nm is assigned to hydrated electrons. Although the direct photoionization of ferrioxalate in water is impossible under photoexcitation of less than 4.7 eV, the fact that an electron to be stripped from iron oxalate into the solvent under the electrostatic attraction of the solvent cannot be ignored. This process is called charge transfer into a solvent. Thus, the reaction may produce hydrated electrons, and the reaction formula is shown as Eq. 4. In the process of electron detachment, the polarization of the iron anions may increase due to the change of the electrostatic interaction between surrounding solvent molecules and ferrioxalate complexes, thereby changing the length of the Fe–O bond [69].

|

(4) |

Previous studies have observed intersystem crossover between low-spin and high-spin configurations in many hexagonal metal complexes [70]. After photoinduced Fe(Ⅱ) spin-crossing, the picosecond extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) has observed that the change of metal coordination bond length is about 0.2 Å [71,72]. For the spin crossing of ferrioxalate complex, the molecule is first excited from ground state (6GS) to high electron state (6ES) with the same spin, and then crosses between the systems to a lower spin state (4ES or 2ES) (Eq. 5). Thus, the structural changes and the absorption differences of ferrioxalate molecular could reflect these spin changes [69].

|

(5) |

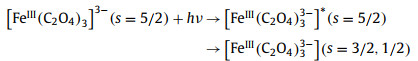

Two most widely debated views are ET from a complexing oxalate ligand to the central iron ion and bond dissociation between them. Several methods are applied to explore the primary photochemical reaction mechanism of ferrioxalate, including flash photolysis, time-resolved XAS, femtosecond pump/probe mid-infrared (MIR) TA spectroscopy and PES. Fig. 3 describes the principle of TA spectroscopy and the advantages and disadvantages of the three main methods.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Principle of different TA spectra. ADC, analog-digital converter; DAC, digital-analog converter. | |

Flash photolysis is an experimental method to study rapid photochemical process. It was first invented by Porter and Norrish [73,74] for the study of chemical reaction kinetics and photochemistry in 1948. This method uses an excitation lamp to generate high-intensity light pulses instantaneously to irradiate the sample, which induce the molecules to achieve photodecomposition or excitation state and generate enough transient molecules to be detected. The absorption spectrum of transient molecules detected by flash lamp or spectral lamp can be directly used to analyze the kinetic process of the reaction. With the application of lasers, experimental devices constructed by laser instead of excitation lamp or spectral lamp has enabled the temporal resolution of transient molecules to reach nanoseconds or even picoseconds.

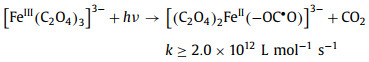

Among early investigations on the photochemical behavior of ferrioxalate between 1910 and 1950 (see more details in Text S2 in Supporting information), flash photolysis was introduced firstly to conduct a detailed study on the photolytic reaction of potassium ferrioxalate by Hatchard and Parker [19] in 1956, in order to establish ferrioxalate as a standard chemical actinometer for photochemical research. In 1959, Parker and Hatchard carried out the preliminary explorations on ferrioxalate solution using flash photolysis [20]. Before that, only Parker and Hatchard used the transient sensing technology to probe the primary photolysis reaction of Fe(Ⅲ)-oxalate, and they had already observed long-lived intermediates. Thus, the intramolecular ET mechanism of ferrioxalate was formally proposed by Parker and Hatchard [20]. Firstly, the change of the first-order constants does not vary with a large change of the initial ferrioxalate concentration, while the second-order "constants" does. Therefore, it is inferred that what is observed is an intramolecular reaction of ferrioxalate. Secondly, the observed long-lived intermediates have greater assimilation ability than ferrioxalate at long wavelengths of 405 nm and 436 nm. Finally, the rate-controlling step takes place before the reduction of the second molecule. It is speculated that the electrons on the ligand are transferred to the central atom after excitation, so that the electron forming one of the bonds between an oxalate ion and the central atom become unpaired. Thus, it is tentatively proposed that the photoreduction mechanism on the nanosecond range includes the initial excitation, followed by dissociation into ferrous oxalate molecules and oxalate anions. Then the oxalate radical reacts with another ferric oxalate ion.

However, a different view emerged in late 1971. DeGraff and Cooper [53] used 340–500 nm irradiation to conduct a more detailed kinetic study. Basing on the observed transient spectra, they concluded that the dissociation between iron center and oxalic ligand prior to intramolecular transfer should also be considered as the major primary reaction [69]. But the rapid reduction of central iron also occurs on the nanosecond range, which is consistent with Parker and Hatchard [20]. Then, another scenario was reported by Rentzepis et al. [75] that electron photolysis also occurs in ferrioxalate complexes. In the process of electron dissociation, the static electricity between the surrounding solvent molecules and Fe(Ⅲ)-oxalate have changed, and the uneven interaction increase the polarization of iron oxalate anions, causing a slight change of the length of the Fe–O bond. Soon after, Jamieson and Perone [66] applied electrochemical measurement techniques to study the secondary photolysis of ferrioxalate solutions irradiated by flash. They found that photoexcitation could cause homolytic cleavage of the C–C bond on the oxalate ligand, which generate two free radicals attached to the ferric dioxalate molecule. Next, the intermediate reacts with ferrioxalate to generate ferrous oxalate. Therefore, the photolysis mechanism about intramolecular ET of ferrioxalate proposed by Parker and Hatchard [20] was denied, because [FeⅡ(C2O4)2]2− and C2O4•− are formed instantaneously, whereas [FeⅡ(C2O4)22−-C2O4•−] is the intermediate of initial photolysis. The experimental observation by Jamieson and Perone [66] showed that the primary intermediate is a ferric diradical containing both reducible and oxidizable groups. Thus, some scholars believe that the reduction of metal ions and the oxidation of oxalate ligands are not the first step in the photoreduction process of metal-oxalate complex [76].

Additionally, based on the previous electrochemical detection method [66], Patterson and Perone [77] tracked the intermediate photoproducts generated by the flash photolysis of ferrioxalate using spectrophotometric and electrochemical monitoring techniques. Since the solution and photolytic conditions used in the earlier flash photolysis studies [66] are different from Parker and Hatchard [20] and DeGraff and Cooper [53], the overall proposed mechanisms are different. Therefore, Patterson and Perone [77] carried out the experiment again under the control of the same conditions. The result showed that the relationship between the absorbance and time of the ferrioxalate solution under flash photolysis is the same as previous researches [20,53] at all wavelengths. The initial reaction process is the dissociation of C—C bond on oxalate, generating ferrioxalate diradical species (Fig. S4 in Supporting information) short-lived substances that can be electrochemically oxidized at −0.1 V [66,76]. Therefore, the intramolecular redox process is the most likely single-molecule reaction that the ferrioxalate diradical specie generate Fe(Ⅱ)-dioxalate, CO2, and CO2•−.

In another study conducted by Nadtochenko and Kiwi [55], the behavior of ferrioxalate complexes under laser irradiation and quenching in the presence of H2O2 were investigated by using 347 nm ruby laser. The absorption of photons and the deactivation of excited substances may occur in the microsecond range. Moreover, with the support of the nanosecond flash photolysis, the view that intramolecular ET is the main cause of the primary photolysis reaction of ferrioxalate is supported by Pozdnyakov et al. [56]. Fig. S5 (Supporting information) illustrates their proposed mechanism of ferrioxalate photolysis [21,31,56]. This is contrary to the conclusion that the FeⅢ–O bond breaks before the ET proposed by Rentzepis and colleagues [69] earlier.

Flash photolysis has opened a road to explore the photochemical reaction process of ferrioxalate. Its long-lived intermediates have been observed by TA, and the reaction rate constant has been determined. But so far, the conflicting views on the reaction characteristics at the molecular level are present in the flash photolysis studies. Furthermore, the data obtained by flash photolysis is insufficient to resolve the dispute over primary photochemistry. Thus, more advanced methods that can detect transient species need to be introduced for probing the ferrioxalate photochemical system.

3.2. Ultrafast high-resolution transient XASTime-resolved XAS is a type of TA spectroscopy that is able to detect transient species. In essence, this method is similar with ultrafast pump-probe detection technology, but the most important component, the detector, is not optical, but absorbed X-ray pulses [78]. Laser pulse excitation is used to initiate a series of basic photochemical processes, and then the reaction intermediates can be detected by XAS to obtain corresponding structural information [79]. Time-resolved XAS is not limited by the time range, and the complex dynamic processes can be clearly observed in the femtosecond field. It is easy to gain information that cannot be obtained from pure laser experiments [78], such as bond length, coordination number. Specifically, XAS mainly includes X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS), X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) and EXAFS. EXAFS and XANES can take transient snapshots of stationary atoms even during rapid chemical reactions. Besides, EXAFS can determine the existence of long-lived transient intermediates based on flash photolysis, and further observe the changes in the Fe–O bond and C—C bond lengths of ferrioxalate after light irradiation. The experimental data of EXAFS [78,79] provide some evidence for the reaction mechanism that the dissociation precedes the intramolecular ET [69].

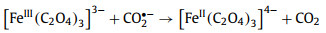

However, Chen et al. [24,68,69] reported that the primary reaction of ferrioxalate after photoexcitation is not intramolecular ET, and there may be another main photochemical process. They used ultrafast pump/probe absorption laser device to examine the Fe–O bond distance measured by EXAFS. Within 0–2 ps after excitation, ferrioxalate is in excited state, and the intermediate Fe–O bond distance is 2.16 Å, about 0.14 Å longer than that of the ground state. In this time frame, neither ET nor ligand dissociation has occurred. Within 4–5 ps after excitation, the length of the Fe–O bond varies from 1.87 Å to 1.93 Å, which is considered as a pentacoordinate [(C2O3)O-FeⅢ(C2O4)2]3−. The reaction process is shown as Eqs. 6–9. In this scenario, no ET take place within 140 ps while the oxalate ligand begins to cleave at 5 ps, generating two CO2•− radicals. Chen et al. [24] provided the following evidences: Firstly, the excited light energy is enough to break the C–C and Fe–O bonds of oxalate molecules. Secondly, the observed Fe–O bond is stretched and the forces between the bonds is weaken, which make it prone to cleavage. Finally, intramolecular ET has a high spatial barrier and is not easy to occur. They argued that dissociation instead of ET dominates, but intermolecular ET cannot be completely excluded. Thus, Chen et al. proposed that the successive cleavages of the Fe–O bond and the C–C bond occur before the ET [31]. However, the experiment only observed and measured the distance of Fe–O bond, while the order of the breakage of Fe–O bond and C–C bond has not been indistinguishable.

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

It is worth noting that different methods of TA spectroscopy would show diverse results. The result proposed by Pozdnyakov et al. [56] in 2008 was queried by Chen et al. [58] who argued that Pozdnyakov et al. misinterpreted their study published in 2007 [68] and thus came to a wrong conclusion. Chen et al. [58] pointed out that previous studies did not provide specific transient spectral data and no experimental data was analyzed, thus denied the view of Pozdnyakov et al. [56] on intramolecular ET. Nevertheless, Cooper and DeGraff [80] suggested that CO2•− free radical-scavenging experiments can distinguish between ET and dissociation. Both Chen et al. and Pozdnyakov et al. carried out the free radical scavenging experiments, but conducted by use of the two different scavengers. Chen et al. used thymine as the CO2•− free radical scavenger, while Pozdnyakov et al. selected methyl viologen dication (MV2+) [56]. They obtained different radical scavenging experimental results [68]. Chen et al. considered that the radical-scavenging reaction would not affect the intramolecular ET process. If ET is the only mechanism, the decrease in the Fe(Ⅱ) amount formed will not exceed 50%. However, using thymine as a CO2•− radical scavenger results in more than 50% decrease of the ΦFe(Ⅱ) in the reaction. It proves strongly that the dissociation is the dominant photoredox reaction and supports the mechanism proposed by Chen et al. [58] of dissociation prior to ET.

Then, Pozdnyakov et al. responded to Chen et al. and adhered the view of ET. They discussed these two views in terms of the properties of Fe(Ⅲ) complexes, the properties of primary photochemical reaction from the free radical species (CO2•− and C2O4•−), the longevity intermediate ferrous oxalate, and oxalic acid [81]. They also responded to the question that no time resolution in the picosecond time range was given. They explained that ET and the cleavage of bond in the molecule are well-known in the picosecond time range. Moreover, regarding free radical scavenging experiments, Pozdnyakov et al. [81] stated that they used a kind of famous electron acceptor, MV2+. On the contrary, Chen et al. [24] chose thymine, which is a poor CO2•− radical scavenger. To understand the photochemistry of ferrioxalate in depth, it is necessary to combine detailed studies of the dynamic behavior of transient substances, the quantum chemical calculations, and the spectral data in the ranges of femtoseconds (fs) to milliseconds (ms).

EXAFS can provide information such as the bond length and coordination number between central atom and coordination atom, but it is not sensitive to the three-dimensional structure and only offers average structural information. Moreover, it does not supply any information about the direction of the bonds. However, XANES can reflect the three-dimensional coordination environment of absorption atoms, which allows to determine the coordination geometry of absorption atoms.

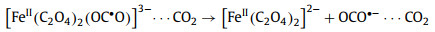

Soon after, a further study on the UV photochemical reactions of ferrioxalate solution was carried out by Ogi et al. [82], who used femtosecond (268 nm) time-resolved XAS. The transition of ferrioxalate from an excited state to a LMCT state was predicted by observing the time evolution of XAS near Fe K-edge and density functional theory calculations. It showed that an initial red-shift by over 4 eV of the K-edge, occurring within the temporal resolution of 140 fs, then it decreases and stabilizes to a value of ~3 eV within ~3 ps, which undergoes no subsequent evolution at least up to 100 ps. However, the magnitude of Fe(Ⅲ) is expected to be smaller than 3 eV. Thus, they speculated that the iron in the reaction product should be divalent. The conclusion is not in accord with that of Chen et al. [69], who reported the blue shift of Fe K-edge under the excitation of 267 nm light. However, the reason for the difference is unclear. In another study, the red shift under 400 nm light excitation was observed by Goldstein and DeGraff [83]. These different results may be due to limited signal-to-noise, which makes it impossible to accurately measure the K-edge shift. Hence, Ogi et al. [82] proposed that the reaction occurs in two steps. Firstly, the excited ferrioxalate undergoes intramolecular ET within 140 fs and loses one CO2 to form [(CO2•)FeⅡ(C2O4)2]3−. Then, the vibrational thermal complex (CO2•− ligand) is dissociated from [(CO2•)FeⅡ(C2O4)2]3− to produce [FeⅡ(C2O4)2]2− within 3 ps. Moreover, the C—C bond of the ligand in the ET state is weakened and then dissociated, and the Fe–O bond gradually elongates. The isomeric form of the transient intermediate is shown in Fig. S6 (Supporting information). Besides, free radical scavenging experiments showed that the ΦFe(Ⅱ) [18,83,84] changed in the presence of scavengers, indicating that the ligand C2O4•− or CO2•− may dissociate from the complex.

In a similar study, a desktop device based on a laser plasma X-ray source and a low-temperature microcalorimeter X-ray detector array was first adopted by O'Neil et al. [85]. Comparing these results with formerly issued transient X-ray absorption measurement results on the same reaction, it is inconsistent with the views of Chen et al. [24,68], but consistent with the conclusion of Ogi et al. [82]. Chen et al. did not discuss the edge shift, but focused on the change of the Fe(Ⅲ)-O bond length, and found that the intermediate's Fe–O bond length is closer to that of Fe(Ⅲ) compound [24,68,69,85]. However, Ogi et al. [82] indicated that the length of Fe–O bond does not change much, but they observed a significant edge shift of −4 eV to −5 eV among 140 fs. Moreover, O'Neil et al. [85] observed an edge shift of −1.85 ± 0.4 eV in the XAS spectrum of intermediate state, which is consistent with Ogi et al. [82]. Thus, it is speculated that the intermediate is Fe(Ⅱ) compound at this moment, which supports view of the rapid ET mechanism. Furthermore, O'Neil et al. [85] indicated that arguments of Chen et al. [24,68,69] are too reliant on the observing changes in Fe–O bond length. They [85] also used two methods to evaluate the change of the ferro-oxygen bond length, but did not find a major variance. Thus, it is not enough to prove that ligand dissociations or fragmentations are primary process just by looking at the change of Fe–O or C–C bond length. Although the time-resolved XAS experiments is sensitive to the change in oxidation states, the associated edge shifts also depends on bond elongation [86] and the ratio of excited substances [87]. Therefore, it is necessary to introduce more advanced methods to ascertain the specific situation of intramolecular ET.

3.3. Resolution pump/probe MIR-TA spectroscopyIR absorption spectroscopy is a well-established and very popular analysis approach widely used in all fields of chemistry. In recent years, TR-IR has become one of the strong tools for exploring photochemical kinetics in solution. TR-IR has structural specificity inherent of IR absorption, and can provide a direct observation of chemical dynamic processes at the molecular level [88]. Compared with the previous time-resolved absorption spectroscopy, it is more characteristic and has higher sensitivity to molecular structure. When studying the photochemical process of substances in solution, TR-IR can be generally carried out through two ways, purely laser-based pump probe spectroscopy and real-time Fourier-transform IR detection spectroscopy after flash photolysis [89]. Therefore, the time gap of the TA spectrum in the past can be filled, and the photochemical process from hundreds of femtoseconds to hundreds of seconds can be scanned almost without delay.

Around 2017, Mangiante et al. [90] studied the photolysis of ferrioxalate in water and heavy water after 3 ns light excitation using pump/probe MIR-TA spectroscopy with 0.1 ps resolution. Fig. S7 (Supporting information) shows the photolysis mechanism of ferrioxalate within 3 ns. The time resolved MIR data showed that intramolecular ET occurred on a sub-picosecond range. After ET, an unstable oxalate anion C2O4•− and two bystander ferrioxalate ligands were produced. Within 40 ps after ET, C2O4•− quickly dissociated into free solvated CO2 and CO2•−, where CO2 is expected to depart the Fe(Ⅱ) coordination sphere during 100 ps, and CO2•− stay at least 10 ns on the coordination sphere. This interpretation largely consistent with that of Ogi et al. [82] whose observations of Fe K edge motion are also consistent with the Vas (C–O) region motion by Mangiante et al. [90] in relation to the transition from ferric to ferrous oxalate.

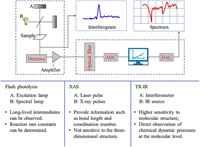

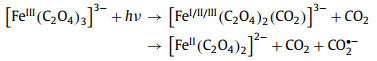

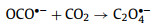

Similarly, the transient spectral method applied by Straub et al. [91,92] is UV-pump/MIR-probe spectroscopy in femtosecond range, which can explore the main reaction process of ferrioxalate as radiometer, namely the kinetics of decarboxylation and the formation of primary intermediates (Fig. 4). After absorbing the 266 nm photons, the excited electrons are transferred rapidly from the complexing oxalate ligand to the central ion, so that the [FeⅢ(C2O4)33−]* in the electronic excited state dissociated into neutral, vibratory CO2 and a penta-coordinated intermediate complex of ferrous dioxalate. This complex has a curved carbon dioxide radical anion ligand (OCO•−) (Fig. S8 in Supporting information). There are three different geometric shapes, square-pyramidal (sp) coordination mode with the OCO•− ligand occupying the apical (ap) binding site, a triangular bipyramidal (tbp) coordination sphere with the OCO•− ligand locating in axial (axe) and equatorial (eq) position. Then, the breakage of Fe–O bond releases CO2•− from the ligand sphere within 400 ps, causing Fe(Ⅲ) reduction to form [FeⅡ(C2O4)2]2−. This as-called thermal decomposition is mainly divided into two continuous processes, Eqs. 10 and 11. Meanwhile, the loose carbonaceous complex can also be isometric as an oxalate anion, according to Eq. 12. However, some shell fragments, such as OCO•−, CO2•− and C2O4•−, might react with another iron oxalate, resulting in the total quantum yield of ferrioxalate more than one.

|

(10) |

|

(11) |

|

(12) |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. The experimental (upper, symbols) and theoretical (lower) infrared spectra of (a) ferric parent, (b) ferrous carbon dioxide complex and (c) ferrous product. Reprinted with permission [92]. Copyright 2022, Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. | |

Of the many reports, Pilz et al. [93] used step-scanning Fourier-transform IR spectroscopy to monitor the primary photolysis process of aqueous ferrioxalate complex under 266 nm irradiation on microsecond-to-millisecond range. By analyzing the latest UV/IR pump probe and ultrafast IR spectral data, the intramolecular transfer mechanism was supported. The photochemical reaction mechanism of ferrioxalate is reorganized as Eqs. 13–15.

|

(13) |

|

(14) |

|

(15) |

Straub et al. [94] revealed the primary changes of light-induced aqueous ferrioxalate by UV-pump/MIR-probe spectroscopy in the femtosecond domain using 266 nm excitation pulses. They monitored the structural changes of the ligand sphere around the iron center in combination with tunable MIR probe pulse and found that the major Fe–O and C–C bond fracture after original photon absorption. After LMCT excitation, the ferrioxalate complex in the excited state is dissociated within 500 fs, and then, the breakages of Fe–O and C–C bond compete with internal conversion, which is required for the CO2-release. In fact, the photochemical mechanism presented by Straub et al. [94] largely elucidates the long-sought molecular level drawing of inner photolysis of ferrioxalate complex. However, the chemical reactivity of the carbon and oxygen center (OCO-ligand) which has significant spin density needs to be explored in future.

3.4. Other methodAs an emerging technique, ultrafast PES can track the oxidation state changes of atoms or molecules by measuring their binding energy [95-97]. It is especially sensitive to the change of the metal oxidation state and its process, so it is widely used to study the ultrafast kinetics of solvated transition metal complexes [98-100]. In the study of Longetti et al. [60], the ferrioxalate complexes in steady-state and transient state were characterized by observing the emission signal from the Fe 3d orbitals in PES. Due to the obvious spectral characteristics of ferric and photogenic ferrous species, changes in the oxidation state of iron center have been well monitored. Combining the results of these three time-resolved methods (XAS [82], fs-IR [91] and PES), Longetti et al. proposed the following initial process of ferrioxalate under photoexcitation (Fig. S9 in Supporting information). The initial step for the photoexcitation of ferrioxalate is a prompt metal photoreduction, occurring on a time less than 30 fs. Thus, the viewpoint of delayed reduction of metal as previously proposed by Chen et al. [69] is not supported, while they confirmed the conclusion by Ogi et al. [82] that the absorption at wavelengths less than 440 nm is due to the LMCT state. Besides, they also observe that about 25% of the reduced species recombined into the steady-state parent ferric molecule in ~2 ps due to the interaction between the dissolved molecules and the solvent molecules after photoreduction. This interpretation resolves some discrepancies found in previous fs X-ray and the TR-IR studies on the initial events of ferrioxalate photolysis. Fig. S10 (Supporting information) illustrates the process of ferrioxalate from photoexcitation to CO2 decomposition. Next, it can be confirmed by further studies using a deep-ultraviolet pump–probe TA study [101] in the LMCT absorption region.

4. ConclusionIt is essential to elucidate the reaction mechanism of ferrioxalate under photoexcitation, especially to clarify the controversy over the primary photolysis mechanism at the molecular level. Understanding its primary mechanisms is crucial to optimizing the reaction pathway. However, throughout the controversy, it has been largely unclear on (ⅰ) whether the formation of the carbonaceous radical anion requires a prior ET from the oxalate ligand to the metal center, (ⅱ) what time range the initial ligand release occurs. A complete picture of the initial photoreaction steps of ferrioxalate is still lacking.

In the past century, with the continuous development of TA spectroscopy, great advances in investigating the reaction mechanism of ferrioxalate photolysis under UV–vis have been made. Flash photolysis opens a road to observe transient intermediates, and XAS could measure the bond length. TR-IR absorption spectroscopy further determines the time range of ET in the primary photochemical reaction of ferrioxalate. According to the reported studies, the view about intramolecular ET precedes dissociation has gained more experimental support. However, the ultimate molecular level mechanism has not been well understood. For instance, which electrons in the oxalate ligand undergo intramolecular ET and the order of cleavages of C—C and Fe–O bonds have not been identified. While ET is believed to occur within sub-picosecond, a more precise time range is not yet clear. Thus, although the intermediates and products of photoreactions are well known, there is no consensus on the original ET mechanism.

Therefore, the significance of this review is to help researchers clearly understand the current status of research on the photolysis process of ferrioxalate by sorting out different existing views. In addition, this review analyzes the advantages and disadvantages of different ultrafast time-resolved methods, which will help to find new methods for in-depth detection of ET and bond dissociation. The subsequent work should make full use of the advantages of existing technologies to achieve more accurate monitoring and analysis of the photochemical reaction process of ferrioxalate through combined methods, and focus on the more precise time range of ET occurrence currently unresolved. Furthermore, previous studies on ferrioxalate are mainly in liquid phase, but there are relatively few cases on other forms of ferrioxalate complex or heterogeneous ferrioxalate. Therefore, the primary photochemical processes in the multiphase media will be an important and challenging work awaiting for in-depth investigation.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41977313). Z. W. thanks the support from the Foundation of Key Laboratory of Yangtze River Water Environment, Ministry of Education (Tongji University), China (No. YRWEF202003) and Key Laboratory of Eco-geochemistry, Ministry of Natural Resources (No. ZSDHJJ202006).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.107752.

| [1] |

K. Kawamura, S. Steinberg, I. Kaplan, Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 19 (1985) 175-188. DOI:10.1080/03067318508077028 |

| [2] |

J. Calvert, A. Lazrus, G. Kok, et al., Nature 317 (1985) 27-35. DOI:10.1038/317027a0 |

| [3] |

T. Fox, N. Comerford, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 54 (1990) 1139-1144. DOI:10.2136/sssaj1990.03615995005400040037x |

| [4] |

Y. Zuo, J. Hoigne, Environ. Sci. Technol. 26 (1992) 1014-1022. DOI:10.1021/es00029a022 |

| [5] |

K. Kawamura, S. Bikkina, Atmos. Res. 170 (2016) 140-160. DOI:10.1016/j.atmosres.2015.11.018 |

| [6] |

J. Yu, X. Huang, J. Xu, M. Hu, Environ. Sci. Technol. 39 (2005) 128-133. DOI:10.1021/es049559f |

| [7] |

A.M. Carlton, B. Turpin, K. Altieri, et al., Atmos. Environ. 41 (2007) 7588-7602. DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.05.035 |

| [8] |

B. Laongsri, R.M. Harrison, Atmos. Environ. 71 (2013) 319-326. DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.02.015 |

| [9] |

T. Guo, K. Li, Y. Zhu, H. Gao, X. Yao, Atmos. Environ. 142 (2016) 19-31. DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.07.026 |

| [10] |

J. Meng, G. Wang, J. Li, et al., Sci. Total Environ. 493 (2014) 1088-1097. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.04.086 |

| [11] |

H. Shen, X. Yan, M. Zhao, S. Zheng, X. Wang, Environ. Exp. Bot. 48 (2002) 1-9. DOI:10.1016/S0098-8472(02)00009-6 |

| [12] |

T.A. Sokolova, Eurasian Soil Sci. 53 (2020) 580-594. DOI:10.1134/s1064229320050154 |

| [13] |

B.W. Strobel, Geoderma 99 (2001) 169-198. DOI:10.1016/S0016-7061(00)00102-6 |

| [14] |

B. Faust, R. Zepp, Environ. Sci. Technol. 27 (1993) 2517-2522. DOI:10.1021/es00048a032 |

| [15] |

A. Allmand, W. Webb, J. Chem. Soc. (Res.) (1929) 1518-1531. |

| [16] |

A. Allmand, W. Webb, J. Chem. Soc. (Res.) (1929) 1531-1537. |

| [17] |

A. Allmand, K. Young, J. Chem. Soc. (Res.) (1931) 3079-3087. |

| [18] |

C.A. Parker, P. Roy, Soc. A Math. Phys. Sci. 220 (1953) 104-116. |

| [19] |

C.G. Hatchard, C.A. Parker, Phys. Eng. Sci. 235 (1956) 518-536. |

| [20] |

C. Parker, C. Hatchard, J. Phys. Chem. 63 (1959) 22-26. DOI:10.1021/j150571a009 |

| [21] |

Z. Wang, W. Song, W. Ma, J. Zhao, Prog. Chem. 24 (2012) 423-432. |

| [22] |

H. Kuhn, S. Braslavsky, R. Schmidt, Pure Appl. Chem. 76 (2004) 2105-2146. DOI:10.1351/pac200476122105 |

| [23] |

K. Aoki, Skin Res. 17 (1975) 29-33. |

| [24] |

J. Chen, H. Zhang, I. Tomov, X. Ding, P. Rentzepis, Chem. Phys. Lett. 437 (2007) 50-55. DOI:10.1016/j.cplett.2007.02.005 |

| [25] |

S. Straub, P. Brünker, J. Lindner, P. Vöhringer, EPJ Web Conf. 205 (2019) 05016. DOI:10.1051/epjconf/201920505016 |

| [26] |

E. Fernández, J. Figuera, A. Tobar, J. Photochem. 11 (1979) 69-71. DOI:10.1016/0047-2670(79)85008-X |

| [27] |

S. Steinberg, K. Kawamura, I. Kaplan, Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 19 (1985) 251-260. DOI:10.1080/03067318508077036 |

| [28] |

F. Joos, U. Baltensperger, Atmos. Environ. A Gen. Top. 25 (1991) 217-230. DOI:10.1016/0960-1686(91)90292-F |

| [29] |

Y. Zuo, Photochemistry of iron(Ⅲ)/iron(Ⅱ) complexes in atmospheric liquid phases and its environmental significance. Ph. D. Dissertation, ETH, Zurich, 1992.

|

| [30] |

T. Kelly, P. Daum, S. Schwartz, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 90 (1985) 7861-7871. DOI:10.1029/JD090iD05p07861 |

| [31] |

D. Gunz, M. Hoffmann, Atmos. Environ. Part A 24 (1990) 1601-1633. DOI:10.1016/0960-1686(90)90496-A |

| [32] |

C. Miles, P. Brezonik, Environ. Sci. Technol. 15 (1981) 1089-1095. DOI:10.1021/es00091a010 |

| [33] |

R. Zepp, B. Faust, J. Hoigne, Environ. Sci. Technol. 26 (1992) 313-319. DOI:10.1021/es00026a011 |

| [34] |

Z. Wang, C. Chen, W. Ma, J. Zhao, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3 (2012) 2044-2051. DOI:10.1021/jz3005333 |

| [35] |

E. Harris, B. Sinha, P. Hoppe, et al., Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12 (2012) 407-423. DOI:10.5194/acp-12-407-2012 |

| [36] |

B. Kocar, W. Inskeep, Environ. Sci. Technol. 37 (2003) 1581-1588. DOI:10.1021/es020939f |

| [37] |

S.J. Hug, H.U. Laubscher, B.R. James, Environ. Sci. Technol. 31 (1997) 160-170. DOI:10.1021/es960253l |

| [38] |

M. Lucas, J. Peres, Dyes Pigment. 74 (2007) 622-629. DOI:10.1016/j.dyepig.2006.04.005 |

| [39] |

D. Prato-Garcia, R. Vasquez-Medrano, M. Hernandez-Esparza, Sol. Energy 83 (2009) 306-315. DOI:10.1016/j.solener.2008.08.005 |

| [40] |

N. Klamerth, S. Malato, M.I. Maldonado, A. Agüera, A. Fernández-Alba, Catal. Today 161 (2011) 241-246. DOI:10.1016/j.cattod.2010.10.074 |

| [41] |

D. Trigueros, A. Módenes, P. Souza, et al., J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 385 (2019) 112095. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2019.112095 |

| [42] |

H. Bates, N. Uri, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 75 (1953) 2754-2759. DOI:10.1021/ja01107a062 |

| [43] |

R. Larson, M. Schlauch, K.A. Marley, J. Agric. Food Chem. 39 (1991) 2057-2062. DOI:10.1021/jf00011a035 |

| [44] |

P. Maruthamuthu, R.E. Huie, Chemosphere 30 (1995) 2199-2207. DOI:10.1016/0045-6535(95)00091-L |

| [45] |

E.G. Solozhenko, N.M. Soboleva, V.V. Goncharuk, Water Res. 29 (1995) 2206-2210. DOI:10.1016/0043-1354(95)00042-J |

| [46] |

Z.M. Li, P.J. Shea, S.D. Comfort, Chemosphere 36 (1998) 1849-1865. DOI:10.1016/S0045-6535(97)10073-X |

| [47] |

L.O. Conte, A.V. Schenone, O.M. Alfano, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 24 (2017) 6205-6212. DOI:10.1007/s11356-016-6400-3 |

| [48] |

A.J. Exposito, J.M. Monteagudo, A. Duran, I. San Martin, L. Gonzalez, J. Hazard. Mater. 342 (2018) 597-605. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.08.069 |

| [49] |

A. Durán, J.M. Monteagudo, A. Carnicer, I. San Martín, P. Serna, Sol. Energy Mat. Sol. C 107 (2012) 307-315. DOI:10.1016/j.solmat.2012.07.001 |

| [50] |

Q. Zeng, S. Chang, M. Wang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 2212-2216. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.12.062 |

| [51] |

Q. Zeng, S. Chang, A. Beyhaqi, et al., Nano Energy 67 (2020) 104237. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.104237 |

| [52] |

C. Parker, Trans. Faraday Soc. 50 (1954) 1213-1221. DOI:10.1039/tf9545001213 |

| [53] |

B. DeGraff, G. Cooper, J. Phys. Chem. 75 (1971) 2897-2902. DOI:10.1021/j100688a004 |

| [54] |

J. Patterson, S. Perone, J. Phys. Chem. 77 (1973) 2437-2440. DOI:10.1021/j100639a015 |

| [55] |

V. Nadtochenko, J. Kiwi, J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 99 (1996) 145-153. DOI:10.1016/S1010-6030(96)04377-8 |

| [56] |

I. Pozdnyakov, O. Kel, V. Plyusnin, V. Grivin, N. Bazhin, J. Phys. Chem. A 112 (2008) 8316-8322. DOI:10.1021/jp8040583 |

| [57] |

I.P. Pozdnyakov, A.A. Melnikov, N. Tkachenko, et al., Dalton Trans. 43 (2014) 17590-17595. DOI:10.1039/C4DT01419G |

| [58] |

J. Chen, A. Dvornikov, P. Rentzepis, J. Phy. Chem. A 113 (2009) 8818-8819. DOI:10.1021/jp809535q |

| [59] |

J. Chen, W.R. Browne, Coord. Chem. Rev. 374 (2018) 15-35. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2018.06.008 |

| [60] |

L. Longetti, T.R. Barillot, M. Puppin, et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23 (2021) 25308-25316. DOI:10.1039/d1cp02872c |

| [61] |

H. Zipin, S. Speiser, Chem. Phys. Lett. 31 (1975) 102-103. DOI:10.1016/0009-2614(75)80067-4 |

| [62] |

J. Šima, J. Makáňová, Coord. Chem. Rev. 160 (1997) 161-189. DOI:10.1016/S0010-8545(96)01321-5 |

| [63] |

C. Weller, S. Horn, H. Herrmann, J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 268 (2013) 24-36. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2013.06.022 |

| [64] |

I. Pozdnyakov, F. Wu, A. Melnikov, et al., Russ. Chem. B 62 (2013) 1579-1585. DOI:10.1007/s11172-013-0227-6 |

| [65] |

P. Borer, S. Hug, J. Colloid Interfaces Sci. 416 (2014) 44-53. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2013.10.030 |

| [66] |

R. Jamieson, S. Perone, J. Phys. Chem. 76 (1972) 830-839. DOI:10.1021/j100650a007 |

| [67] |

P. Kennepohl, E. Solomon, Inorg. Chem. 42 (2003) 696-708. DOI:10.1021/ic0203320 |

| [68] |

J. Chen, H. Zhang, I. Tomov, et al., J. Phys. Chem. A 111 (2007) 9326-9335. DOI:10.1021/jp0733466 |

| [69] |

J. Chen, H. Zhang, I. Tomov, P. Rentzepis, Inorg. Chem. 47 (2008) 2024-2032. DOI:10.1021/ic7016566 |

| [70] |

C. Brady, J. McGarvey, J. McCusker, et al., Time-resolved relaxation studies of spin crossover systems in solution. In: Spin crossover in transition metal compounds III, Top. Curr. Chem., 235, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2004, pp. 1–22.

|

| [71] |

M. Khalil, M.A. Marcus, A.L. Smeigh, et al., J. Phys. Chem. A 110 (2006) 38-44. DOI:10.1021/jp055002q |

| [72] |

R.K. Pandey, S. Mukamel, J. Phys. Chem. A 111 (2007) 805-816. DOI:10.1021/jp0627022 |

| [73] |

P.R G. Porter, Soc. A Math. Phys. Sci. 200 (1950) 284-300. |

| [74] |

R.G.W.N.G. Porter, Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Sci. 210 (1952) 439-460. |

| [75] |

P. Rentzepis, R.P. Jones, J. Jortner, Chem. Phys. Lett. 15 (1972) 480-482. DOI:10.1016/0009-2614(72)80353-1 |

| [76] |

F. Duke, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 69 (1947) 2885-2888. DOI:10.1021/ja01203a073 |

| [77] |

J.I.H. Patterson, S.P. Perone, J. Phys. Chem. 77 (1973) 2437-2440. DOI:10.1021/j100639a015 |

| [78] |

C. Bressler, M. Chergui, Chem. Rev. 104 (2004) 1781-1812. DOI:10.1021/cr0206667 |

| [79] |

L. Chen, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 56 (2005) 221-254. DOI:10.1146/annurev.physchem.56.092503.141310 |

| [80] |

G.D. Cooper, B.A. DeGraff, J. Phys. Chem. 76 (1972) 2618-2625. DOI:10.1021/j100662a027 |

| [81] |

I. Pozdnyakov, O. Kel, V. Plyusnin, V. Grivin, N. Bazhin, J. Phys. Chem. A 113 (2009) 8820-8822. DOI:10.1021/jp810301g |

| [82] |

Y. Ogi, Y. Obara, T. Katayama, et al., Struct. Dyn. 2 (2015) 034901. DOI:10.1063/1.4918803 |

| [83] |

S. Goldstein, J. Rabani, J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 193 (2008) 50-55. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2007.06.006 |

| [84] |

C. Weller, S. Horn, H. Herrmann, J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 255 (2013) 41-49. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2013.01.014 |

| [85] |

G.C. O'Neil, L. Miaja-Avila, Y.I. Joe, et al., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8 (2017) 1099-1104. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b00078 |

| [86] |

M. Kubin, M. Guo, T. Kroll, et al., Chem. Sci. 9 (2018) 6813-6829. DOI:10.1039/c8sc00550h |

| [87] |

C. Bressler, R. Abela, M. Chergui, Z. Krist. Cryst. Mater. 223 (2008) 307-321. DOI:10.1524/zkri.2008.0030 |

| [88] |

P. Vohringer, Dalton Trans. 49 (2020) 256-266. DOI:10.1039/c9dt04165f |

| [89] |

H. Graener, A. Laubereau, Opt. Commun. 54 (1985) 141-146. DOI:10.1016/0030-4018(85)90279-2 |

| [90] |

D.M. Mangiante, R.D. Schaller, P. Zarzycki, J.F. Banfield, B. Gilbert, ACS Earth Space Chem. 1 (2017) 270-276. DOI:10.1021/acsearthspacechem.7b00026 |

| [91] |

S. Straub, P. Brunker, J. Lindner, P. Vohringer, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20 (2018) 21390-21403. DOI:10.1039/C8CP03824D |

| [92] |

S. Straub, P. Brunker, J. Lindner, P. Vohringer, Angew. Chem. 130 (2018) 5094-5099. DOI:10.1002/ange.201800672 |

| [93] |

F.H. Pilz, J. Lindner, P. Vohringer, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21 (2019) 23803-23807. DOI:10.1039/c9cp05233j |

| [94] |

S. Straub, P. Brünker, J. Lindner, P. Vöhringer, EPJ Web of Conferences 205 (2009) 0516. |

| [95] |

O. Link, E. Lugovoy, K. Siefermann, et al., Appl. Phys. A 96 (2009) 117-135. DOI:10.1007/s00339-009-5179-1 |

| [96] |

F. Buchner, A. Lübcke, N. Heine, T. Schultz, Rev. Sci. Instrum. 81 (2010) 113107. DOI:10.1063/1.3499240 |

| [97] |

H. Okuyama, Y.I. Suzuki, S. Karashima, T. Suzuki, J. Chem. Phys. 145 (2016) 074502. DOI:10.1063/1.4960385 |

| [98] |

A. Moguilevski, M. Wilke, G. Grell, et al., ChemPhysChem 18 (2017) 465-469. DOI:10.1002/cphc.201601396 |

| [99] |

M. Borgwardt, M. Wilke, I. Kiyan, E. Aziz, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18 (2016) 28893-28900. DOI:10.1039/C6CP05655E |

| [100] |

J. Ojeda, C. Arrell, L. Longetti, M. Chergui, J. Helbing, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19 (2017) 17052-17062. DOI:10.1039/C7CP03337K |

| [101] |

M. Chergui, J. Chem. Phys. 150 (2019) 070901. DOI:10.1063/1.5082644 |

2023, Vol. 34

2023, Vol. 34