b Institute of Environmental and Health Sciences, College of Quality and Safety Engineering, China Jiliang University, Hangzhou 310018, China;

c State Nuclear Security Technology Center, Beijing 102401, China;

d China Institute for Radiation Protection, Taiyuan 030000, China

Plutonium (Pu) is an important anthropogenic radionuclide with high toxicity [1, 2], which is closely associated with the nuclear industry. Until now, more than 30 Pu isotopes have been found. Pu isotopes, such as 239Pu (t1/2 = 2.41 × 104 y), 240Pu (t1/2 = 6.56 × 103 y), 241Pu (t1/2 = 14.4 y), 242Pu (t1/2 = 3.76 × 105 y), gained more attention since the longer half-life and their important application in nuclear industry and environment [1]. Until now, nuclear accidents [3-5] and the atmospheric nuclear tests are the major sources of Pu in the environment. Recent studies have shown that the nuclear accidents such as Fukushima nuclear power plant accident and Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident have caused serious radioactive contamination in the atmosphere. The major Pu isotope released was 239Pu, and the residual 239Pu in the reactor could generate 240Pu, 241Pu, 242Pu through the further neutron capture reaction [6, 7]. It was estimated that the total amount of 239, 240Pu discharged from the Fukushima nuclear accident to the environment was about 1.03 × 109 Bq to 2.4 × 109 Bq, which was almost one ten-thousandth of the Chernobyl nuclear accident emissions (8.7 × 1013 Bq) [3], one in a million of the atmospheric nuclear test (1.1 × 1016 Bq) (UNSCEAR, 1995) [8]. Anthropogenic radionuclide Pu is characterized as particle reactive and could attach to the surface of atmospheric non-radioactive inert particles (such as mineral dust). Also, it was particularly likely to form submicron radioactive aerosol particles and concentrated in the fine particles with size less than 0.49 µm [9]. Besides, Pu-bearing particles had a large diffusion coefficient, which could stably disperse in the atmosphere or transmit to the remote area with the airflow. However, the particles were finally settled to the ground through the dissolution and chemical reaction with water droplets. The settled radioactive particles could combine with surface soil particles and further resuspend into upper atmosphere because of wind. This process could affect the concentration of Pu in the local area, and in turn, reflected the surface soil physical resuspension processes and long-distance transmission behavior of dust pollutant [2]. Although the activity concentrations of radionuclides in the atmosphere were at low level, particles containing high radiation toxicity Pu may cause long-term damages to human health once entered the body through the respiratory system [10]. Therefore, it is of great significance to monitor Pu activity concentrations and atom ratios in the atmosphere.

Pu atom ratios have provided remarkable environmental tracing significance, especially the 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio. The 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio could be applied as environmental tracer to distinguish the global fallout from the other sources and events [11-13]. To date, the characteristics of Pu in the atmosphere affected by local Pu sources were well understood [14, 15]. However, the monitoring of Pu in the atmosphere that free of various Pu sources were rather scarce, and the atmospheric Pu activity concentrations, atom ratios and sources in aerosol samples were little known. To perform the source appointment of Pu contaminant, a good knowledge of Pu activity concentrations and atom ratios were required, as well as characteristic signatures of different sources observed in a designated location. However, some studies pointed out that Pu activity concentrations in the air were at ultra trace level, generally ranged from 10−7–10−8 Bq/m3 (10−17–10−18 g/m3), which were extremely lower than the reported levels in some contaminated area [8]. Therefore, the analytical technique with extremely low detection limit (fg level) was necessary for the analysis of atmospheric Pu. Consequently, the free of polyatomic interference and excellent detection limit of accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) become a competitive tool to analyze the long-live radionuclides Pu, as well as their atom ratios [16-18].

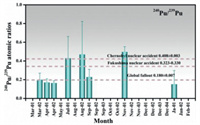

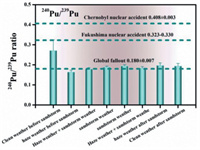

Pu from various sources are characterized with different concentrations and atom ratios. As shown in Fig. S1 (Supporting information), the 240Pu/239Pu atom ratios varied with the type of weapon and the explosive equivalent in the nuclear test, and changed with the reactor type and the nuclear fuel. One of the most important atmospheric Pu sources was global fallout with a well-known 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio characteristic of 0.180 ± 0.007 [19]. Other important sources were the Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident and Fukushima nuclear power plant accident derived Pu with typical 240Pu/239Pu atom ratios of 0.408 ± 0.003 [20] and 0.323–0.330 [21], respectively. Pu in nuclear weapons were characterized with a low 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio, ranging from 0.01 to 0.07 [22, 23], while the nuclear reactor one was featured with a relatively higher 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio, ranging from 0.4 to 0.67 [24]. Therefore, the atom ratios of 240Pu/239Pu could be served as a fingerprint for tracing the source of Pu contamination.

Recently, Chamizo et al. [11] found that long-range transport of dust aerosols (dust Sahara) had a significant effect on 239Pu and 240Pu concentrations in the Seville atmosphere (Receptor region), which could be attributed to the transported of "hot" particles or Pu-bearing soil particles in the contaminated areas after the nuclear activities or nuclear accident. Choi et al. [25] also found that the resuspended soil particles during Yellow Sand events contributed greatly to the elevating of Pu activity concentration in Korea and Japan. Radionuclides released from atmospheric nuclear weapons test were mainly settled down to the surface through the following three ways [26, 27]. Larger radioactive particles (50–100 µm) could quickly settle down near the test area. Radioactive particles with a size of 1–10 µm might remain in the troposphere for several hours to several months and therefore widely spread to remote area. Due to the horizontal diffusion of troposphere atmosphere, radioactive particles (1–10 µm) mainly settled down to the similar latitude zone. However, radioactive particles smaller than 1 µm could reach to the stratosphere and stay for a long time, transporting with the atmospheric circulation. Therefore, except for nuclear tests and nuclear accidents, the soil resuspension maybe the additional Pu sources in the atmosphere [28].

Here we used a highly sensitive AMS to analyze the long-lived radionuclides Pu, as well as their atom ratios. Specific objectives of this study were to (i) analyze and compare pollution characteristics of atmospheric Pu (including the Pu activity concentration, atom ratio, and seasonal variation trend) in a year-round aerosol samples and sandstorm samples, (ii) characterize the possible sources of atmospheric Pu, and (iii) study the potential of Pu isotope to be an environmental tracer in source identification of sandstorm in the atmosphere of Beijing.

The total suspended particulates (TSP) samples were collected using a high-volume TSP sampler in Beijing. Samples were collected during non-sandstorm in 2016 and the sandstorm season in the March of 2018. A total of 2873 m3 TSP was collected for each sample. The samples were weighed before and after sampling for TSP mass calculation, and then stored in the polyethylene sealed bags under −20 ℃ before analyzing. Detail information such as sample time and sampling volume was presented in Table 1 and Table S1 (Supporting information). Pu isotopes and trace elements Al on the collected TSP samples were measured in this study. The method for Pu isotopes analysis was adapted from our previous work [29]. The sample was spiked with 0.5 pg 242Pu for chemical yield monitoring and isotopic dilution, and then fused with 2.5 g LiBO2, 0.3 g LiI and 0.03 g Na2S2O8 in the muffle under a temperature ramping program. After that, sample was dissolved with HNO3 and HCl. The sample was added with PEG-6000 and stirred for 30 min. After centrifugation, a certain amount of TiOCl2 were added to the sample solution and pH was adjusted to 7–8. After that, precipitate was dissolved with concentrated HNO3 with a proportion of 1:1 and NaNO2 was added to adjust the valence of Pu. TEVA chromatographic column was applied for the further Pu purification. After pre-conditioned with 10 mL 8 mol/L HNO3, the sample solution was loaded to the resin. 8 mol/L HNO3 and concentrated HCl were uses to remove sample matrix, uranium and thorium. Pu was eluted with 10 mL 0.1 mol/L HCl + 0.01 mol/L HF. 0.4 mg Ti and 0.1 mg Fe standard solution was added to the Pu solution, while pH was adjusted to > 9. The precipitate was recovered, dried and mixed with niobium powder for AMS analysis. The pre-treatment procedures were strictly quality controlled to avoid any possible contamination to the samples. IAEA 384 and IAEA 385 were used here for method validation. The measured data were fit well with the reference information. The method detection limit (MDL) of 239Pu and 240Pu were 0.3 fg and 11.3 fg, respectively.

|

|

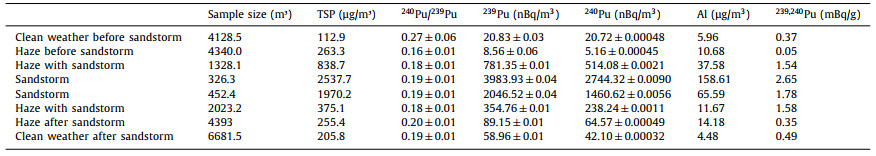

Table 1 The activity concentrations and atom ratios of plutonium isotopes during the sandstorm occurred in Beijing in 2018. |

The obtained results (239Pu, 240Pu, 241Pu activity concentration) in the year-round aerosol month samples were shown in Fig. 1 and Table S1. As shown in Figs. 1a and b, 239Pu activity concentrations in the atmosphere were in the range of 0.62 ± 0.04~99.60 ± 2.33 nBq/m3, and 240Pu activity concentrations ranged from 3.50 ± 1.24 nBq/m3 to 60.23 ± 8.52 nBq/m3. The obtained Pu isotopes concentrations in Beijing were similar to the reported Pu activity concentrations levels in elsewhere, such as Vilnius and Chihuahuan desert with 239, 240Pu activity concentrations of 1–16 nBq/m3 and 12.1–15.1 nBq/m3, respectively [15, 30, 31]. The detection rate of 239Pu, 240Pu and 241Pu were 100%, 64% and 0, respectively. The reason that no 241Pu was detected and only a few of samples were detected with 240Pu was that the only source of Pu isotopes in atmospheric environment in Beijing was global fallout and no nuclear event was happened here or around. Therefore, the following discussions were mainly focused on 239Pu and 240Pu.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Variation trend of plutonium isotopes activity concentration and TSP concentration in the aerosol samples: (a, b) 239Pu and 240Pu of the TSP samples collected in Beijing in 2016, respectively; (c, d) 239Pu and 240Pu of the TSP samples collected during the sandstorm occurred in Beijing in 2018, respectively. | |

239Pu and 240Pu in the atmosphere of Beijing showed an identical seasonal variation pattern, with the higher value (239Pu: 99.60 ± 2.33, 240Pu: 60.23 ± 8.52 nBq/m3) in spring and lower value (239Pu: 0.62 ± 0.04, 240Pu: 2.26±1.77 nBq/m3) in winter (Table S1), suggesting the same source of 239Pu and 240Pu in aerosol sample. The possible source of Pu isotopes maybe the resuspended soil particles when sandstorm frequently happened in spring time in Beijing. Also, previous study have found that the decreasing of Pu activity concentrations in the atmosphere might be attributed to the precipitation, which could result in a higher value in dry season and a lower value in rainy season [11]. Our results agreed well with the climatic characteristics of Beijing, with low rainfall in spring and maximum rainfall in summer. The data obtained in our study and the climate characteristic in Beijing implied that the activity concentration of Pu was influenced by climatic conditions and had a regional season characteristic.

In order to confirm 239Pu and 240Pu in the atmosphere was related to dust storms, we collected sand storm samples during the sand storm event happened in March 2018. The results of 239Pu and 240Pu in sandstorm samples were presented in Figs. 1c and d and Table 1. It could be seen from the figure that higher concentrations were observed for 239Pu and 240Pu during the sandstorm period, with the high value up to 3983.98 ± 0.04 nBq/m3 and 2744.32 ± 0.04 nBq/m3 for 239Pu and 240Pu, respectively. It was significantly higher than the maximum values (99.6 ± 2.33 nBq/m3 and 60.23 ± 8.52 nBq/m3 for 239Pu and 240Pu) observed in month samples. Obviously, when sandstorm occurred, the suddenly increasing of TSP concentration resulted in 239Pu and 240Pu concentration increase. 239Pu and 240Pu activity concentration in sandstorm weather was higher than the value in haze weather and mixed weather of haze and sandstorm. Besides, the 239Pu and 240Pu activity concentration in sandstorm weather were higher than those in haze weather before sandstorm, about 465 times and 503 times. Above all, the highest 239Pu and 240Pu activity concentration was observed in spring of Beijing, when sandstorms frequently happened in spring in Beijing, further suggested that Pu was involved in sandstorm.

When comparing the 239Pu and 240Pu concentration in haze weather after sandstorm to those in sandstorm weather, it was significantly decreased. These suggested that sand source was the major source of 239Pu and 240Pu in the atmosphere of Beijing when sandstorm occurred. The contribution of haze source was neligible. Besides, for sandstorm samples, 239Pu, 240Pu activity concentration and TSP concentration showed a similar variation trend, but for year-round samples are inconsistent (Figs. 1a and b). Therefore, aerosol samples collected during the sandstorm implied that the Pu activity would correlate with the TSP concentration. Based on the results mentioned above, we can preliminarily infer the tracer significance of Pu in sandstorm.

240Pu/239Pu atom ratio has also been employed to identify sources of Pu in urban atmosphere [30]. 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio varied with different sources of Pu, which could serve as a fingerprint for tracing the source of Pu contamination in the atmosphere [32-35]. At present, the anthropogenic radionuclides Pu in the atmosphere was mainly derived from nuclear tests and nuclear accidents such as the Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident and the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident. As shown in Fig. 2 and Table S1, the 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio in the atmosphere of Beijing in 2016 ranged from 0.17 to 0.50, with an average value of 0.29. It was higher than the global fallout and significantly different from nuclear weapons 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio (0.01–0.007). Since only five samples were detected with 240Pu in the year-round aerosol samples, it was difficult to give a specific explanation of the higher 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio. However, if we exclude the outlier of 0.50 ± 0.06, the average 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio was 0.19, which was consistent with characteristic of global fallout. As for the higher 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio of 0.50, even though the data were similar to the characteristic of nuclear accident, the only one sample detected with a higher atom ratio could not be attributed to Fukushima or Chernobyl nuclear accident. The atmospheric circulation and the non-volatile characteristic of Pu could not support this conclusion. In short, high ratios of the 240Pu/239Pu more than 0.4 observed in aerosol samples collected in 1/11 in 2016 may be attributed to the uncertainty of low level of 240Pu in the measurement process. Therefore, a large number of aerosol samples should be collected and investigated for the deep research of Pu sources in the future. Fig. 3 illustrated the 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio in the aerosol samples collected during the sandstorm occurred in 2018. It could be seen that most of 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio varied around 0.18, which was the recognized characteristic atom ratio of global fallout. However, the samples obtained in clean weather before sandstorm showed an obvious higher 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio (0.27 ± 0.06) than other samples and the average ratio of global fallout (0.18 ± 0.01), which may attributed to the not well measured 240Pu. Although the special ratio (0.27 ± 0.06) is closed to the typical 240Pu/239Pu atom ratios (0.323–0.330) of Fukushima nuclear power plant accident, the only one sample detected with a higher atom ratio (0.27 ± 0.06) could not be attributed to Fukushima nuclear accident atmospheric circulation and the non-volatile characteristic of Pu could not support this conclusion. Therefore, the characteristic 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio during the sandstorm period could be inferred to be associated with global fallout.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. The 240Pu/239Pu atmo ratio in the aerosol samples collected in Beijing in 2016. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. The 240Pu/239Pu atmo ratio in the aerosol samples collected during the sandstorm occurred in Beijing in 2018. | |

239, 240Pu concentration in form of mBq/g was discussed here to further clarify the sources of Pu in atmosphere of Beijing. From Table 1 we could see that TSP samples showed a higher 239, 240Pu concentration when sandstorm occurred, ranging from 1.54 mBq/g to 2.65 mBq/g. It was much higher than samples collected in clean weather or haze weather before and after sandstorm. Furthermore, in the year-round TSP samples, 239, 240Pu concentration was in the range of 0.01–0.86 mBq/g, with an average concentration of 0.09 mBq/g. When sandstorm occurred, soil particles were the major component in aerosol samples. Pu concentration in aerosol samples was only affected by Pu absorbed on soil particle. At the same time, it was reported that the source of sandstorm was the desert area of the southern Mongolia and Inner Mongolia. The 239, 240Pu concentration in surface soil of southern Mongolia was in the range of 0.42–3.53 mBq/g, with an average of 1.59 mBq/g [36]. Also, higher 239, 240Pu concentration was found in desert area of Inner Mongolia [37]. Our data in sandstorm samples were similar to that in the soil samples in the desert area. Combining the report on the sources of sandstorm in Beijing and the similar concentration of 239, 240Pu between TSP and soil samples in the desert area, it could be seen that the soil dust transported from remoted area was a major source of Pu in atmosphere of Beijing. When considering the year-round TSP samples, most of the samples showed 239, 240Pu concentration in the range of 0.01–0.07 mBq/g, which was much lower than in local soil samples (average 0.1 mBq/g). Under non-sandstorm weather condition, local soil particle was not the only source of atmospheric particles, secondary particles or other sources such as industrial source, automobile emission source, contributed most of particles to the atmosphere. Moreover, according to results of atmospheric particle source appointment, soil particle in the local area accounted for 10%–30% of atmospheric particle [38]. Our data were consistent with source appointment results from the aspect of 239, 240Pu concentration. In general, Pu isotopes in atmospheric samples were derived from the soil particle resuspension.

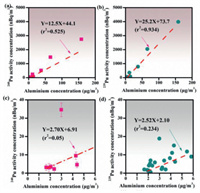

Soil resuspension has been suggested to be one of the important natural sources of Pu in the atmosphere. Using aluminum (Al) as an indicator of soil resuspension, the contribution of the resuspended surface soil was evaluated by investigating the relationship between 239Pu, 240Pu and Al. As shown in Fig. 4, significant positive correlations between 239Pu and Al (r2 = 0.934), between 240Pu and Al (r2 = 0.525) have been observed in the TSP samples collected during the sandstorm occurred in 2018 (Figs. 4a and b). The high correlation demonstrated that soil resuspension was a primary source of atmospheric Pu during the sandstorm period in Beijing. Similar results were also found in aerosol samples collected from Chihuahuan desert [31]. However, a weak correlation was observed between 239Pu, 240Pu and Al in the year-round TSP month samples (r2 = 0.05, and r2 = 0.234) (Figs. 4c and d). Since dust source was not the only source of atmospheric particles in normal weather condition, other sources such as industrial source or automobile emission source that containing no anthropogenic Pu contributed most part of atmospheric particles. Therefore, the lack of correlation between Pu and Al in the month TSP samples collected in 2016 indirect proved that the proportion of resuspended soil particles in the aerosol was not so high. The correlation results in the two different type of aerosol samples indicated that higher concentration of Pu in the atmosphere were mainly attributed to higher TSP concentration with soil dust as the main component. After clearly identifying the primary sources of Pu and its correlation with Al, it could be concluded that 239Pu and 240Pu could be used as two potential tracer of sandstorms, which may have a potential application in the source apportionment of sandstorm occurred in Beijing. Besides, due to the significant positive correlation between Pu and Al, 239Pu/Al ratio (12.5 µBq/g) or 240Pu/Al ratio (25.2 µBq/g) could act as tracers of sandstorm, which could also be applied for the source apportionment of sandstorm of Beijing.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Correlation between concentrations of 239Pu, 240Pu and Al in the aerosol samples. (a, b) The correlation between 240Pu and Al (r2 = 0.525) and 239Pu and Al (r2 = 0.934) of the sandstorm samples collected during the sandstorm occurred in 2018. (c, d) The correlation between 240Pu and Al (r2 = 0.05) and 239Pu and Al (r2 = 0.234) of the year-round samples collected in Beijing in 2016. | |

There were experimental evidences showing that the anthropogenic radionuclide 239Pu and 240Pu in the atmosphere of Beijing were at ultra trace level. The concentrations of 239Pu and 240Pu were observed the highest in spring and the lowest in winter, which indicated the soil resuspension was the major source of 239Pu and 240Pu in the atmosphere of Beijing. Pu concentration in aerosol samples collected during dust storms was much higher than that during non-dust storms. Above all, significant positive correlation between 239Pu and Al (r2 = 0.934), 240Pu and Al (r2 = 0.525) implied that soil resuspension during the sandstorms period was the major source of the present atmospheric Pu. Pu atom ratios along with Pu isotopes concentration in aerosol samples provided remarkable environmental tracing significance, which could be used as fingerprint in sandstorm sources. The two can be combined to trace the source of dust. Meanwhile, 239Pu/Al ratio and 240Pu/Al ratio were two potential tracers that could be applied in source identification of sandstorm. Although the number of storm samples is indeed small, the purpose of this work is preliminary exploration the potential application of plutonium isotopes in source identification of sandstorm, and lay a foundation for its tracer application. Therefore, it will provide reference for further research in this field in the future. Future work will be conducted on a large number of storm samples to further elucidate the tracer significance of atmospheric plutonium isotopes.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the financial supports from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U1932103, U1832212, 11875266), Key Deployment Projects of Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. ZDRW-CN-2018–1) and Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. 7191008).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.030.

| [1] |

J.H. Harley, J. Radiat. Res. 21 (1980) 83-104. DOI:10.1269/jrr.21.83 |

| [2] |

K. Hirose, Y. Igarashi, M. Aoyama, et al., J. Environ. Radioact. 101 (2010) 106-112. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2009.09.003 |

| [3] |

K. Hirose, P.P. Povinec, Sci. Rep. 5 (2015) 15707. DOI:10.1038/srep15707 |

| [4] |

A. Sakaguchi, P. Steier, Y. Takahashi, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 48 (2014) 3691-3697. DOI:10.1021/es405294s |

| [5] |

N. Casacuberta, M. Christl, K.O. Buesseler, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 51 (2017) 9826-9835. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.7b03057 |

| [6] |

P. Thakur, H. Khaing, S. Salminen-Paatero, J. Environ. Radioact. 175-176 (2017) 39-51. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2017.04.008 |

| [7] |

M.P. Johansena, D.P. Childa, T. Cresswell, et al., Sci. Total Environ. 691 (2019) 572-583. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.531 |

| [8] |

UNSCEAR. Publications. Source and effects of Ionizing radiation. Fuel. Energy. Abstract 36 (1995) 220

|

| [9] |

D.D. Gay, J.R. Watts, Jour (1981). DOI:10.2172/5249678 |

| [10] |

A.S. Aliyu, N. Evangeliou, T.A. Mousseau, et al., Environ. Int. 85 (2015) 213-228. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2015.09.020 |

| [11] |

E. Chamizo, M. García-León, S.M. Enamorado, et al., Atmos. Environ. 44 (2010) 1851-1858. DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.02.030 |

| [12] |

Y. Hao, Y. Xu, S. Pan, et al., Mar. Pollut. Bull. 130 (2018) 240-248. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.03.037 |

| [13] |

M.E. Ketterer, K.M. Hafer, J.W. Mietelski, J. Environ. Radioact. 73 (2004) 183-201. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2003.09.001 |

| [14] |

P. Thakur, H. Khaing, S. Salminen-Paatero, J. Environ. Radioact. 175 (2017) 39-51. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2017.04.008 |

| [15] |

T. Shinonaga, K. Guckel, M. Yamada, et al., Geochem. J. 55 (2021) 33-38. DOI:10.2343/geochemj.2.0615 |

| [16] |

E. Chamizo, S.M. Enamorado, M. García-León, et al., Nucl. Ins. Meth. Phys. Res. Sec. B 266 (2008) 4948-4954. DOI:10.1016/j.nimb.2008.08.001 |

| [17] |

X.L. Zhao, W.E. Kieser, X.X. Dai, et al., Nucl. Ins. Meth. Phys. Res. Sec. B 294 (2013) 356-360. DOI:10.1016/j.nimb.2012.01.056 |

| [18] |

K. Hain, T. Faestermann, L. Fimiani, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 51 (2017) 2031-2037. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.6b05605 |

| [19] |

J.M. Kelley, L.A. Bond, T.M. Beasley, Sci. Total. Environ. 237-238 (1999) 483-500. DOI:10.1016/S0048-9697(99)00160-6 |

| [20] |

T. Shinonaga, P. Steier, M. Lagos, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 48 (2014) 3808-3814. DOI:10.1021/es404961w |

| [21] |

J. Zheng, K. Tagami, S. Uchida, Environ. Sci. Technol. 47 (2013) 9584-9595. DOI:10.1021/es402212v |

| [22] |

T. Warneke, I.W. Croudace, P.E. Warwick, et al., Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett. 203 (2002) 1047-1057. DOI:10.1016/S0012-821X(02)00930-5 |

| [23] |

J.W. Mietelski, B. Was, Isotopes. 46 (1995) 1203-1211. DOI:10.1016/0969-8043(95)00162-7 |

| [24] |

E. Iranzo, S. Salvador, C.E. Iranzo, Health. Phys. 52 (1987) 453-461. DOI:10.1097/00004032-198704000-00006 |

| [25] |

M.S. Choi, D.S. Lee, J.C. Choi, et al., Sci. Total Environ. 370 (2006) 262-270. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.07.036 |

| [26] |

S. Xing, Trace Application of Long-Lived Radionuclides 239, 240Pu and 129I in the Environment, Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, PhD thesis, 2015.

|

| [27] |

G. Lujaniene, V. Aninkevicius, V. Lujanas, J. Environ. Radioact. 100 (2009) 108-119. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2007.07.015 |

| [28] |

S.Oikawa M.Yamada, Y. Shirotani, et al., J. Environ. Radioact. 227 (2021) 106459. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2020.106459 |

| [29] |

X.X. Dai, M. Christl, S. Kramer-Tremblay, et al., J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 27 (2012) 126-130. DOI:10.1039/C1JA10264H |

| [30] |

G. Lujanienė, D. Valiulis, S. Byčenkienė, et al., Atmos. Environ. 61 (2012) 419-427. DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.07.046 |

| [31] |

P. Thakur, S. Ballard, R. Nelson, J. Environ. Monitor. 14 (2012) 1604-1615. DOI:10.1039/c2em30027c |

| [32] |

J. Lehto, X. Hou, Chemistry and Analysis of Radionuclides, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2011

|

| [33] |

S.G. Tims, S.E. Everett, L.K. Fifield, et al., Nucl. Ins. Meth. Phys. Res. Sec. B 268 (2010) 1150-1154. DOI:10.1016/j.nimb.2009.10.121 |

| [34] |

P. Lindahl, S.H. Lee, P. Worsfold, et al., Mar. Environ. Res. 69 (2010) 73-84. DOI:10.1016/j.marenvres.2009.08.002 |

| [35] |

D. Arnold, W. Kolb, Isotopes 46 (1995) 1151-1157. DOI:10.1016/0969-8043(95)00158-a |

| [36] |

K. Hirose, Y. Kikawada, Y. Igarashi, et al., J. Environ. J. Environ. Radioact. 166 (2017) 97-103. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2016.01.007 |

| [37] |

W. Zhang, X. Hou, H. Zhang, et al., Environ. Pollut. 289 (2021) 117967. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117967 |

| [38] |

C. Liang, F. Duan, K. He, et al., Environ. Int. 86 (2016) 150-170. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.016 |

2022, Vol. 33

2022, Vol. 33