b NHC Key Laboratory of Nuclear Technology Mediccal Trasnformation (Mianyang Central Hospital), Mianyang 621900, China;

c Key Laboratory of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging of Sichuan Province, Mianyang 621999, China;

d Department of Nuclear Medicine, The Affiliated Hospital Southwest of Medical University, Luzhou 646000, China

As the third most common type of diagnosed cancer, colorectal cancer (CRC) has 2 million new cases in 2020, and it is also the second most common cause of cancer death (almost 1 million deaths annually) worldwide [1]. Among CRC diagnoses, 20% have metastatic CRC [2], another 25% with the localized tumor will develop into metastases later [3], and 40% of localized diseases recur after treatment [4]. Metastatic CRC has a poor prognosis, whose 5-year survival rate is not over 20% [2].

Surgery is typically the first treatment for most CRC [5]. Systemic therapy is the primary treatment for unresectable metastatic CRC, including cytotoxic chemotherapy, immunotherapy, biologic therapy, radiation therapy, and their combinations [3]. Since monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) can bind the corresponding target antigens with high affinity and specificity, mAbs therapy is a promising molecular targeted therapy for CRC. In addition to their application in independent immunotherapy, mAbs can also be utilized for antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) therapy or radioimmunotherapy (RIT) [6]. One of the reasons that the latter has broad clinical applications for cancer treatment [7, 8] is the biological half-life of mAbs matches the physical half-life of the commonly used therapeutic radionuclide compared to small molecules such as peptides. The therapeutic radionuclide labeled mAbs could cause DNA double-strand break in tumor cells, which induces cell death and decreases the antibody-induced resistance [9-11]. The therapeutic radionuclide Lutetium-177 (177Lu) has received considerable attention due to its β emission energy (E = 497 keV) and suitable half-life (6.7 days) [12, 13]. The 177Lu radiolabeled mAbs are considered to be a promising cancer therapeutic agent [14-16].

Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), also known as Sialyl Lewis A, is a ligand for epithelial leukocyte adhesion molecules [17], and its overexpression plays a principal part in the invasion and metastasis of many cancers, including CRC [18]. As one of the most representative tumor markers in CRC [19-22], CA19-9 presents on the cellular membrane of tumor cells in more than 56% of CRC patients [23]. While the serum CA19-9 level of patients with metastatic CRC is only significantly higher than that of asymptomatic tumor patients or the healthy controls by about 35% to 40%, there was no noteworthy difference between the latter two groups [24]. Thus, serum CA19-9 estimation is valueless for asymptomatic CRC screening [25]. However, both serum level and immunohistochemical expression of CA19-9 have been considered as prognostic indicators for CRC patients [22, 23]. The relatively high expression of CA19-9 in CRC patients suggests that it can be an attractive target for developing CRC-specific targeting agents. In addition, a single CA19-9 bearing multi epitopes [26] gives it a theoretical advantage over other protein tumor antigens, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). Hence, we wondered whether effective radioisotope-labeled CA19-9 mAbs could work as radiopharmaceuticals for unresectable metastatic CRC. Though the natural characteristics of mAbs are suitable for targeting tumors [27], ideal mAbs for RIT should present high uptake, long retention in tumors, and low uptake in major organs. Here, a systematic Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging study of a series of CA19-9 mAbs was performed to screen a potential candidate for RIT. In brief, the mAbs were radiolabeled with zirconium-89 (89Zr) for screening a mAb with high tumor-specific uptake via PET/CT imaging, then the screened mAb was labeled with 177Lu, and the anti-tumor efficacy was evaluated for CRC (Fig. 1). As far as we known, it is the first time that a radiolabeled CA19-9 mAb was developed for CRC treatment.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Scheme of screening for a 177Lu-labeled CA19-9 mAb via PET imaging of 89Zr-labeled CA19-9 mAbs for CRC therapy. | |

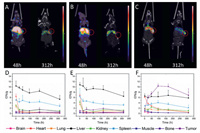

Three mAbs (C001, C002 and C003), as representative candidates for targeting CA19-9, were radiolabeled with 89Zr. The conjugation scheme and structure of 89Zr-DFO-mAb are illustrated in Fig. 1. And the radiochemical purity (RCP) of 89Zr-DFO-C001, 89Zr-DFO-C002, and 89Zr-DFO-C003 were greater than 98% in terms of the instant thin-layer chromatography (iTLC) (Fig. S1 in Supporting information). The in vivo biodistribution of the 89Zr-mAbs was investigated in BALB/c mice bearing colo205 xenografts. And the micro-PET/CT images were recorded at a series of time points after administration (Figs. 2A-C and Fig. S2 in Supporting information) Based on the analysis of PET/CT imaging, the time-activity curves were utilized for further interpreting the pharmacokinetics (Figs. 2D-F).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Micro-PET/CT imaging of 89Zr-DFO-C001 (A), 89Zr-DFO-C002 (B), and 89Zr-DFO-C003 (C) at 48 h and 312 h in colo205 tumor-bearing mice, the red circles indicate the tumor location. The pharmacokinetics of 89Zr-DFO-C001 (D), 89Zr-DFO-C002 (E), and 89Zr-DFO-C003 (F) in colo205 tumor-bearing mice via analysis of PET/CT imaging (n = 3/group). | |

The tumor accumulation of 89Zr-DFO-C001 and 89Zr-DFO-C002 was low (Figs. 2A and B), which increased slightly and gradually until 168 h. Uptake in the cardiac blood pool was notable at 1 h post-injection, which decreased significantly at 24 h and was almost negligible after 48 h. The rapid clearance of 89Zr-DFO-C001 and 89Zr-DFO-C002 from circulation may be a reason that induces low tumor uptake. Meanwhile, the liver uptake decreased gradually after reaching its peak at 1 h post-injection, indicating that the hepatobiliary clearance is fast. This result is consistent with the rapid decline of blood uptake. Generally, the low tumor uptake and poor pharmacokinetics suggest that C001 and C002 are not optimal candidates for CA19-9 targeted radiotherapy.

The screen was continued until C003 was found. Compared with 89Zr-DFO-C001 and 89Zr-DFO-C002, 89Zr-DFO-C003 presented relatively lower liver uptake within 312 h. Notable uptake in cardiac blood was also observed with 89Zr-DFO-C003 at 1 h, while it decreased slower than the other two candidates, which increases the possibility of tumor uptake. The tumor uptake of 89Zr-DFO-C003 was observable at 24 h post-injection and then continually increased to 10.35 ± 0.78 %ID/g at 96 h, which kept higher than the liver uptake from 24 h to 312 h. According to the imaging exposure dose of tissue, 89Zr-DFO-C003 also exhibited the best tumor-targeting efficacy (Fig. S3 in Supporting information). Hence, C003 was selected for 177Lu labeling and subsequent RIT due to its high tumor targeting.

The binding affinity determination of C003 and DOTA-C003 shows these two mAbs displayed similar specific binding affinity to CA19-9-positive colo205 cells (Fig. S4 in Supporting information), which suggests that conjugation with DOTA does not affect the binding ability significantly. The scheme of conjugation and structure of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 are shown in Fig. 1. The average conjugation number of DOTA on every C003 molecule is 3.19 ± 0.15, which was determined via a spectrophotometric method as described previously [28]. An aliquot of 177LuCl3 (~185 MBq) was incubated with 2.5 mg of DOTA-C003 in NaOAc buffer (0.5 mol/L, pH 5.5) at 40 ℃ for 1 h. The RCP of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 was greater than 98% (Fig. S5 in Supporting information). The specific activity of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 was calculated to be 74 MBq/mg. Size-exclusion HPLC analysis of the 177Lu-DOTA-C003 shows a single peak whose retention time corresponds to the unlabeled C003 (Fig. S6 in Supporting information), which indicates that there was no aggregation, and conjugation and radiolabeling did not destroy the structure of C003. For further investigation, the good in vitro stability of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 has been proved with > 95% of activity in saline and > 86% in 10% FBS at ambient temperature for 120 h (Table S1 in Supporting information), which indicates 177Lu-DOTA-C003 is stable enough for future in vitro and in vivo studies.

All the in vitro cell studies were performed with CA19-9 positive colo205 cells. The immunoreactive fraction (IRF) determined by the Lindmo assay was 86.9% (Fig. 3A). 177Lu-DOTA-C003 could specifically bind colo205 cells, while the value of half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) was 206 nmol/L (Fig. 3B), which is about an order higher than that of other targeted mAbs to their corresponding target cells. The saturation binding amount (Bmax) of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 with colo205 cells (1 × 105) is also relatively high up to 74.97 ± 2.23 nmol (Fig. 3C), which indicates that the maximum binding of each colo205 cell is 0.75 fmol on average. The reasons may be the high expression of CA19-9 on the surface of colo205 cells and a single CA19-9 bearing multi epitopes. And the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) was 0.22 ± 0.02 nmol/L, suggesting 177Lu-DOTA-C003 shows good binding affinity to CA19-9.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Quality control of 177Lu-DOTA-C003. (A) The immunoreactive fraction of 177Lu-DOTA-C003. (B) Saturation cell-binding studies of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 performed with colo205 cells. (C) Determination of Kd and Bmax. | |

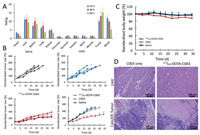

The biodistribution study of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 was also performed in colo205 tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the PET imaging analysis of 89Zr-DFO-C003, 177Lu-DOTA-C003 also exhibited high blood uptake at 24 h post-injection and then decreased gradually to 5.19 ± 1.62 %ID/g at 96 h. At the same time, the liver uptake kept relatively stable from 11.22 ± 1.52 to 9.23 ± 3.06 %ID/g from 24 h to 96 h, indicating the 177Lu-DOTA-C003 was mainly hepatic metabolism. And the relatively high tumor uptake of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 increased from 10.03 ± 1.35 %ID/g (24 h) to 15.18 ± 2.56 %ID/g (96 h) suggests it could be a candidate for RIT. Then we further investigated the anti-tumor effect of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 and C003 on colo205 xenografts. RIT using radiolabeled mAbs is an effective cancer treatment strategy, whose main advantage is the combination of ionizing radiation and mAbs effect. Because cytotoxic radionuclides can bind antigens on the surface of tumor cells specifically via mAbs and then targeting release the cytotoxic radiation [29-32]. In addition, radiotherapy can induce a systemic anti-tumor immune response [33-36]. It was hypothesized that the addition of radiotherapy could improve treatment effects without introducing new chemotherapy drugs. For the C003 group, the tumor-bearing mice were injected intravenously with 5 mg/kg of C003, repeated 14 days after the first treatment (Fig. S7 in Supporting information). At the same time, the tumor-bearing mice of the 177Lu-DOTA-C003 group were treated with an aliquot of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 (~7.4 MBq) following the same procedure. The tumor-bearing mice injected with saline work as the control group. As shown in Fig. 4B, the average standardized tumor volume (STV) of the C003 group (328% ± 40%) and the control group (358% ± 28%) were significantly higher than that of the 177Lu-DOTA-C003 group (221% ± 33%) after 15 days of treatment. This result shows that the 177Lu-DOTA-C003 presents significantly stronger therapeutic efficacy than the unlabeled C003 with the same dose of mAb. The STV of the 177Lu-DOTA-C003 group is 315% ± 67%. The survival period of the 177Lu-DOTA-C003 group was significantly longer than that of the other two groups (P < 0.05) (Fig. S8 in Supporting information). Compared with the control group, C003 immunotherapy was not enough to inhibit tumor growth alone at the dose of 5 mg/kg, and there was no noteworthy difference between the C003 group and the control group (P > 0.05). According to these results, the essential role of 177Lu induced radiotherapeutic effect has been proved in the therapy of CA19-9-positive tumor models.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Anti-tumor treatment study and biosafety evaluation of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 and C003 in BALB/c mice with colo205 xenografts. (A) Biodistribution of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 in colo205 xenografts at 24 h, 48 h and 96 h (n = 3). (B) The standardized tumor volume (STV) of colo205 tumor-bearing mice (n = 5). (C) Record of standardized bodyweight of colo205 tumor-bearing mice (n = 5). (D) H & E staining of liver and tumor tissues from C003 control and 177Lu-DOTA-C003 group after treatment. | |

For RIT, potential toxicity is the reason for limiting radiation doses and causing side effects of treatment [37]. In our group, the body weights of the mice in the 177Lu-DOTA-C003 group were found to decrease about 10% (P < 0.05), whereas the C003 group and the control group did not show any decrease (Fig. 4C). For evaluating the side effect, histological analysis of the liver was performed in the C003 group and the 177Lu-DOTA-C003 group after treatment. The H & E staining confirmed the livers of the mice treated with 177Lu-DOTA-C003 had a few hemorrhagic spots, which were not observed in the liver tissue of the C003 group (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that the 177Lu-DOTA-C003 treatment may have some side effects caused by the accumulation of 177Lu. A large amount of tumor tissue necrosis can be observed in the radiotherapy group, while the tumor tissue of the C003 group showed no apparent change. Taken together, these results indicated 177Lu-DOTA-C003 presents limited toxicity and accepted biosafety for RIT, and could induce the damage of the tumor.

The combination of the specific tumor-targeting mAbs and the suitable radionuclide provides an effective strategy for the diagnostic imaging of tumors, therapy effect evaluation, and tumor-targeting ionizing radiation delivery [27]. Differences in the target antigen expressed level and the specific targeting ability of mAbs affect the tumor uptake efficacy of mAbs and therapeutic effect [38]. CA19-9 is overexpressed in some CRC, while its expression level is relatively low in normal tissues. Moreover, a single CA19-9 bearing multi epitopes makes it more advantageous as a tumor target, which is suitable for some novel treatment strategies, such as RIT. In this study, the CA19-9 mAbs conjugated with DFO or DOTA were successfully prepared. The theranostic role of 89Zr/177Lu-labeled CA19-9 mAbs was evaluated in colo205 xenografts. 89Zr-DFO-mAbs could differentiate the biodistribution of mAbs in vivo, which is useful for screening the mAb with high tumor uptake. Among the three candidates, 89Zr-DFO-C003 showed high uptake of about 10 %ID/g in the CA19-9-positive tumor and low uptake in non-target tissues, which provides good tumor contrast and may be useful for CA19-9-targeted diagnosis. Thus, C003 was chosen as a highly tumor-targeting candidate for 177Lu labeling and the following RIT. The good in vitro stability of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 has been proved with no off-labeling and degradation after incubation for 120 h in 10% FBS and PBS, which is critical for RIT. Moreover, the 177Lu-DOTA-C003 could specifically bind colo205 cells in vitro, and effectively inhibit the growth of colo205 xenografts compared with the other two groups treated with unlabeled C003 and saline. Also, limited toxicity was observed by 177Lu-DOTA-C003 in the immunohistochemical analysis. Hence, 89Zr/177Lu labeled C003 provides an effective approach for the theranostic of CA19-9-positive CRC.

It should be pointed out that some limitations in this study require more attention in future work. First of all, the study was only performed in mice bearing colo205 xenografts. In addition, both the determination of the appropriate dose and the timing of administration are crucial for maximizing the therapeutic efficacy, so more research work is required to figure out the optimal combination. Lastly, as the shed and circulating CA19-9 cannot be ignored in clinical practice, a preloading strategy is required for improving tumor uptake, increasing tumor-to-tissue ratios, and reducing uptake in non-target tissues.

In summary, a highly specific CA19-9 mAb (C003) was screened via Micro-PET/CT imaging and worked as a candidate for 177Lu labeling and following RIT. An aliquot of 177Lu-DOTA-C003 (~7.4 MBq/mouse) displayed a significantly better treatment efficacy than the 5 mg/kg immunotherapy, and there was no noticeable observation of side effects. This is the first time that a radiolabeled CA19-9 mAb was developed for CRC treatment. Both the 89Zr-DFO-C003 for CRC immune-PET imaging and the 177Lu-DOTA-C003 for radiotherapy against CRC exhibit good potential in clinical application.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21976167, U20A20384), the CAEP Innovation and Development Foundation (No. CX20200003), Nuclear Energy Development Project of State Administration of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense (No. 20201192-1), Key R & D Project of Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2020YFS0030), the Central Guidance for Local Science and Technology Development Projects (No. 202138-03). Special thanks to Prof. Tong Zhou and Ms. Zhe Li from Sinotau Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. for providing mAbs and performing the histological analysis.

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.056.

| [1] |

Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month 2021, Available online: https://www.iarc.who.int/news-events/colorectal-cancer-awareness-month-2021/. [Accessed November 11, 2021]

|

| [2] |

Cancer Stat Facts: Colorectal Cancer, Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html. [Accessed November 11, 2021]

|

| [3] |

L.H. Biller, D. Schrag, JAMA 325 (2021) 669-685. DOI:10.1001/jama.2021.0106 |

| [4] |

C.J. Kahi, C.R. Boland, J.A. Dominitz, et al., Gastroenterology 150 (2016) 758-768. e711. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.001 |

| [5] |

S. Stintzing, F1000Prime Rep. 6 (2014) 108. DOI:10.12703/P6-108 |

| [6] |

M.D. Girgis, T. Olafsen, V. Kenanova, et al., Int. J. Mol. Imaging 2011 (2011) 834515. DOI:10.1155/2011/834515 |

| [7] |

Z.N. Chen, L. Mi, J. Xu, et al., Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 65 (2006) 435-444. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.12.034 |

| [8] |

M.M. Andrade-Campos, A.E. Montes-Limón, G. Soro-Alcubierre, et al., Ann. Hematol. 93 (2014) 1985-1992. DOI:10.1007/s00277-014-2145-6 |

| [9] |

D.L. Costantini, C. Chan, Z. Cai, et al., J. Nucl. Med. 48 (2007) 1357. DOI:10.2967/jnumed.106.037937 |

| [10] |

S.V. Govindan, R. Stein, Z. Qu, et al., Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 84 (2004) 173-182. DOI:10.1023/B:BREA.0000018417.02580.ef |

| [11] |

F. Forrer, J. Chen, M. Fani, et al., Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 36 (2009) 1443-1452. DOI:10.1007/s00259-009-1120-2 |

| [12] |

F.F. Guillermina, E.O.-G. Blanca, L.S.C. Clara, et al., Curr. Radiopharm. 8 (2015) 150-159. DOI:10.2174/1874471008666150313115423 |

| [13] |

A. Vilchis-Juárez, G. Ferro-Flores, C. Santos-Cuevas, et al., J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 10 (2014) 393-404. DOI:10.1166/jbn.2014.1721 |

| [14] |

E.J. Razumienko, J.C. Chen, Z. Cai, et al., J. Nucl. Med. 57 (2016) 444-452. DOI:10.2967/jnumed.115.162339 |

| [15] |

J.S. Batra, M.J. Niaz, Y.E. Whang, et al., Urol. Oncol. 38 (2020) 848. e849-848. e816. |

| [16] |

M.C. Yeh, B.W.C. Tse, N.L. Fletcher, et al., EJNMMI Res. 10 (2020) 46. DOI:10.1186/s13550-020-00637-x |

| [17] |

M.K. Gupta, R. Arciaga, L. Bocci, et al., Cancer 56 (1985) 277-283. DOI:10.1002/1097-0142(19850715)56:2<277::AID-CNCR2820560213>3.0.CO;2-M |

| [18] |

R. Kannagi, M. Izawa, T. Koike, et al., Cancer Sci. 95 (2004) 377-384. DOI:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03219.x |

| [19] |

H. Katoh, K. Yamashita, Y. Kokuba, et al., World J. Surg. 32 (2008) 1130-1137. DOI:10.1007/s00268-008-9535-7 |

| [20] |

V. Liska, , V. Treska, et al., Anticancer Res. 27 (2007) 2861-2864. DOI:10.1016/j.schres.2009.05.024 |

| [21] |

T.C. Mineo, V. Ambrogi, G. Tonini, et al., J. Am. Coll. Surg. 197 (2003) 386-391. DOI:10.1016/s1072-7515(03)00387-9 |

| [22] |

W.S. Wang, J.K. Lin, T.J. Chiou, et al., Hepatogastroenterology 49 (2002) 160-164. DOI:10.1046/j.1523-5378.7.s1.2.x |

| [23] |

Y. Ikeda, M. Mori, A. Kido, et al., Am. J. Gastroenterol. 86 (1991) 1163-1166. DOI:10.3109/00365529109003964 |

| [24] |

X. Filella, R. Molina, J.J. Grau, et al., Ann. Surg. 216 (1992) 55-59. DOI:10.1097/00000658-199207000-00008 |

| [25] |

W.M. Thomas, J.F. Robertson, M.R. Price, et al., Br. J. Cancer 63 (1991) 975-976. DOI:10.1038/bjc.1991.213 |

| [26] |

L. Mare, A. Caretti, R. Albertini, et al., Inter. J. Biochem. Cell B 45 (2013) 792-797. DOI:10.1016/j.biocel.2013.01.004 |

| [27] |

N. Dammes, D. Peer, Theranostics 10 (2020) 938-955. DOI:10.7150/thno.37443 |

| [28] |

E. Dadachova, L.L. Chappell, M.W. Brechbiel, Nucl. Med. Biol. 26 (1999) 977-982. DOI:10.1016/S0969-8051(99)00054-2 |

| [29] |

O.M. Ozpiskin, L. Zhang, J.J. Li, Theranostics 9 (2019) 1215-1231. DOI:10.7150/thno.32648 |

| [30] |

A.K. Erdi, Y.E. Erdi, E.D. Yorke, et al., Phys. Med. Biol. 41 (1996) 2009-2026. DOI:10.1088/0031-9155/41/10/011 |

| [31] |

S.M. Larson, J.A. Carrasquillo, N.K.V. Cheung, et al., Nat. Rev. Cancer 15 (2015) 347-360. DOI:10.1038/nrc3925 |

| [32] |

T.M. Allen, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2 (2002) 750-763. DOI:10.1038/nrc903 |

| [33] |

E.J. Van Limbergen, D.K. De Ruysscher, V.Olivo Pimentel, et al., Br. J. Radiol. 90 (2017) 20170157. DOI:10.1259/bjr.20170157 |

| [34] |

R.S.A. Goedegebuure, L.K. de Klerk, A.J. Bass, et al., Front. Immunol. 9 (2018) 3107. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2018.03107 |

| [35] |

M. Xu, Y. Han, G. Liu, et al., Mol. Pharm. 15 (2018) 4426-4433. DOI:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00371 |

| [36] |

J. Ren, M. Xu, J. Chen, et al., Theranostics 11 (2021) 304-315. DOI:10.7150/thno.45540 |

| [37] |

J.A. Torok, J.K. Salama, Nat. Rev. Clinical Oncol. 16 (2019) 666-667. DOI:10.1038/s41571-019-0277-2 |

| [38] |

A. Sabet, H.J. Biersack, S. Ezziddin, Semin. Nucl. Med. 46 (2016) 40-46. DOI:10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2015.09.005 |

2022, Vol. 33

2022, Vol. 33