Liver cancer is one of the most common gastrointestinal tumors with its increasing incidence. The overall survival rate and recurrence rate of patients are still not ideal, and the prognosis is poor [1-3]. Therefore, a new strategy is needed to improve the therapeutic effect of liver cancer.

Newcastle disease virus (NDV) is an avian paramyxovirus in the genus Avulavirus [4]. NDV can replicate efficiently in tumor cells, induce apoptosis, and exhibit oncolytic effect [5-7]. In recent years, it has been considered one of the most promising oncolytic viruses by scientists [8]. However, wild-type NDV has not achieved the desired therapeutic effect. With the development of genetic engineering, researchers modified NDV by inserting target genes to construct oncolytic virus with specific functions, further enhancing its oncolytic effect [9-11].

Extracellular matrix (ECM) is a network complex composed of highly cross-linked proteins present in all tissues and organs. However, ECM limits intratumoral spread and penetration of drugs [12-16]. Studies have found that the poor spreading of the virus is related to ECM physical barrier within the tumor [17, 18]. Therefore, ECM as a therapeutic target may be a feasible method to increase the transmission of oncolytic viruses.

Matrix metalloproteinase 8 (MMP8) is the member of collagenase subgroup in the MMP superfamily [19]. It is produced by neutrophils [20]. It is also found in epithelial cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, and endothelial cells [21, 22]. MMP8 has proteolytic activity [23], and its ability to degrade collagen which is the main component of ECM, is higher than that of MMP1 and MMP13 [24]. In addition, MMP8 can cleave other proteins, including proteoglycans, fibronectin, and fibrinogen [25].

At present, studies have shown that recombinant oncolytic viruses expressing ECM degrading enzymes (such as relaxin [26], MMP9 [27], and hyaluronidase [28]) can enhance virus distribution in tumor masses and improve the effect of anti-tumor [29-31]. In addition, remodeling the ECM of tumor tissue using collagenase delivery improves the distribution of the virus in the tumor [32-35]. In this study, we constructed a recombinant NDV expressing MMP8 and observed its anti-tumor therapeutic effect.

The NDV LaSota strain was used to construct the recombinant NDV-MMP8. The DNA fragment encoding human MMP8 (Gene bank Accession No. XM_011542836) was isolated from the plasmid PcDNA3.1-MMP8 (Sangong Biotech, China) with the following primer pair: 5′-AGGTCCAACTCTGTTTAAACTTAGAAAAAATACGGGTAGAAGTGCCACCATGTTCTCCCTGAAG-3′ and 5′-ATTGCCGCTTGGGTTTAAACGCCATATCTACA-3′. The amplified MMP8 gene cDNA was sequenced and cloned into Pme I site between the P and M genes of the NDV LaSota [36]. The resultant plasmid encoding MMP8 gene was named pLa-MMP8. The recombinant NDV viruses were then rescued by transfecting BSR T7/5 cells with pLa-MMP8 along with the three helper plasmids, namely, pBSNP, pBSP, and pBSL [37]. The supernatant was harvested after 72 h at 37 ℃, and then incubated into the nine-day-old embryonated SPF eggs. The allantoic fluid was harvested, and the virus was identified by hemagglutination assay using chicken red blood cells at 72 h post-infection. The recombinant virus was named as NDV-MMP8 (Fig. 1A).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Construction and characteristics of recombinant virus. (A) Structural diagram of the recombinant virus. (B) Expression of MMP8 in HepG2, MHCC97H cells by Western blot. 1, NDV group. 2, NDV-MMP8 group. (C) Secretion level of MMP8 in the supernatant of HepG2 and MHCC97H cells by ELISA in triplicate. (D) Cell viability at the indicated MOI and time points by CCK8 kit in triplicate. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). | |

To confirm the expression of MMP8, HepG2 and MHCC97H cells were infected with NDV-WT or NDV-MMP8 at MOI of 1 for 48 h. The expression of MMP8 in HepG2 and MHCC97H cells infected with virus was confirmed by Western blot (Fig. 1B). To assess the level of MMP8 expession mediated by recombinant virus, HepG2 and MHCC97H cells were treated with NDV-MMP8 at MOI = 2, 5, 10. Two days after infection, the expression level of MMP8 in culture supernatants was assessed by ELISA. As shown in Fig. 1C, the results indicated that MMP8 expression was dose-dependent. To examine the cytopathic effect in vitro, cell viability was detected by CCK8 assay at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. As shown in Fig. 1D, NDV-MMP8 effectively inhibit the proliferation of tumor cells, cell viability gradually decreased in time-dependent and dose-dependent conditions.

To analyze whether NDV-MMP8 degraded ECM, we established tumor xenogeneic mode by subcutaneously injecting six-week-old male BALB/c nude mice with 5 × 106 HepG2 and MHCC97H cells. Animal experiments were authorized by the Animal Use and Care Committee of Guangxi Medical University. Tumors (100–150 mm3) received three intratumoral injections of PBS or 107 PFU of each virus once every other day. Three days after the last injection of virus, the mice were put to death after anesthesia, and the tumor tissues were collected. We studied the expression of collagen in Masson's trichrome staining, the percentage of collagen area was analyzed in multiple images with Image Pro-Plus software. As shown in Fig. 2, PBS group and NDV-WT group had extensive collagen distribution, and NDV-MMP8 group significantly decreased collagen content (P < 0.001). These results demonstrate that MMP8 effectively degrade the collagen of ECM, weaken the virus transmission barrier.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. NDV expressing MMP8 effectively degrades ECM collagen. In the established HepG2 and MHCC97H cancer models, intratumoral injections of 200 µL PBS, 107 PFU NDV and 107 PFU NDV-MMP8 were performed every other day for three times. The tumors were collected on the third day after the last injection. (A) Expression of collagen by Masson's trichrome staining. Image magnification: × 400. (B) The percentage of collagen area. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 8). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA test (***P < 0.001). | |

To evaluate whether the expression of MMP8 and collagen degradation improved the spread of intratumoral virus, the fluorescent signal of expressing NDV as a sign of virus spread was detected by immunofluorescence assay. As shown in Fig. 3A, the NDV-MMP8 group detected more fluorescence signal of NDV in the tumor tissue than the NDV-WT group. To test whether NDV-MMP8 can increase the viral load of tumors, the virus titer of NDV-WT group and NDV-MMP8 group was analyzed by TCID50 assay. We use the homogenized lysate of tumor tissue to detect the virus titer on BSR T7/5 cells. As shown in Fig. 3B, in the HepG2 and MHCC97H tumor models, the average virus titers of the NDV-MMP8 group were 8.3 times and 10.2 times that of the NDV-WT group, respectively. These findings indicate that NDV-MMP8 increase virus distribution by degrading ECM, and increase the number of intra-tumoral infectious virus particles.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. NDV expressing MMP8 enhances the spread of the virus in liver cancer model. In the established HepG2 and MHCC97H cancer models, intratumoral injections of 200 µL PBS, 107 PFU NDV and 107 PFU NDV-MMP8 were performed every other day for three times. The tumors were collected on the third day after the last injection. (A) Virus expression and distribution by immunofluorescence assay. Magnification: × 400. (B) Virus titer of tumor tissue homogenate (TCID50/g tissue). Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). | |

To explore the therapeutic effect, the tumor tissue was estimated by histological assay. HE staining (Fig. 4A) showed the tumors treated with NDV-MMP8 had a large number of necrotic areas with pyknosis and fragmentation of their nuclei, where as necrotic areas were rarely detected in tumors in other groups. TUNEL staining (Fig. 4B) showed that the NDV-MMP8 group had a larger area of apoptotic tumor cell, and few apoptotic cells were detected in the other two groups. The percentage of positive cells was analyzed in multiple images with Image Pro-Plus software. As shown in Fig. 4C, we found that the apoptotic cells in the NDV-MMP8 group were significantly higher (P < 0.001) than the PBS group and the NDV group. These results suggest that NDV-MMP8 improve the ability to induce tumor cell apoptosis.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Histological staining and TUNEL staining. In the established HepG2 and MHCC97H cancer models, intratumoral injections of 200 µL PBS, 107 PFU NDV and 107 PFU NDV-MMP8 were performed every other day for three times. The tumors were collected on the third day after the last injection. (A) HE staining. Magnification: × 400. (B) TUNEL staining. Magnification: × 400. (C) The percentage of TUNEL positive cells. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 8). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA test (***P < 0.001). | |

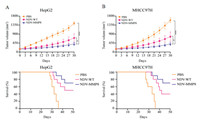

To evaluate the anti-tumor effect of NDV-MMP8, we used six-week-old male BALB/c nude mice injecting with 5 × 106 HepG2 and MHCC97H cells to establish two liver cancer xenograft models. When tumors reached 150 mm3, mice were randomized and divided into three groups. Seven mice in each group were used to observe tumor volume, and ten mice in each group were used to observe mice survival. Mice were treated with intratumoral injections of 200 µL 107 PFU NDV-WT or NDV-MMP8 or PBS every other day for five times. Tumor progression was monitored every other day, and tumor volume was calculated using the following formula: 0.5 × X × Y2 (X: length, Y: width). At the same time, the survival of mice was observed every day. In the HepG2 xenograft model (Fig. 5A), the tumors in the PBS group and the NDV-WT group grew rapidly, and the tumor volume increased by 9.61 times and 4.7 times on the 30th day. However, the tumors in the NDV-MMP8 group showed slow growth rates, and the tumor volume only increased by 2.67 times. Similar results were obtained from the MHCC97H xenograft model (Fig. 5B), the tumors of the PBS group and NDV-WT group increased by 10.4 times and 5.1 times, and only 2.69 times in the NDV-MMP8 group.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Anti-tumor effect in liver cancer xenograft model. When the average tumor volume of mice reached 150 mm3, tumors were injected with NDV or NDV-MMP8 intratumorally every other day for five times. (A) Tumor volume (n = 7) and Kaplan–Meier survival curve (n = 10) in HepG2 cancer xenograft models. (B) Tumor volume (n = 7) and Kaplan–Meier survival curve (n = 10) in MHCC97H cancer xenograft models. A caliper is used to measure the size of the tumor. Data represent mean ± SD (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). | |

Oncolytic viruses (OVs) are emerging promising anti-cancer agents. OVs can selectively replicate in tumor cells and induce systemic anti-tumor immunity [38]. With the characteristics of effective oncolytic effect and non-pathogenic to humans, NDV is an ideal natural OV in cancer treatment. However, due to the body's strong immune effects and cross-linked extracellular environment, NDV has an attenuated effect on the human body [17]. In this research, virus-mediated gene encoding ECM-degrading protein promotes virus spread and enhances therapeutic efficacy.

MMP8 is the first matrix metalloproteinase to be used as an anti-target for cancer therapy [39]. Some studies have shown that MMP8 has the potential to inhibit tumorigenesis or metastasis [40-42]. The anti-tumor effect of the recombinant virus shown in this study may also be related to the anti-cancer mechanism of MMP8. Here, MMP8 only plays the role of degrading ECM or jointly plays its anti-tumor effect, which needs to be further explored and studied. However, studies have shown that intratumoral administration of NDV activated innate immunity and increased the expression of T-cell costimulatory receptors. Next, further work is required to research the mechanism of immune feedback such as CTLA-4 and ICOS induced by NDV [43].

In conclusion, our research shows that the Newcastle disease virus expressing MMP8 overcomes the ECM barrier, improves the transduction and transmission efficiency of the virus, and increases anti-tumor efficacy. We believe that the new strategy of promoting viral spread by degrading stromal barriers to enhance therapeutic efficacy has broad prospects in clinical research and treatment.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis research was supported by the Scientific and Technological Innovation Major Base of Guangxi (No. 2018–15-Z04), Guangxi Key Research and Development Project (No. AB20117001), Guangxi Science and Technology Bases and Talent Special Project (No. AD17129062) and Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (No. 2018JJA140524).

| [1] |

J. Ferlay, M. Colombet, I. Soerjomataram, et al., Int. J. Cancer 144 (2019) 1941-1953. DOI:10.1002/ijc.31937 |

| [2] |

J.L. Petrick, S.P. Kelly, S.F. Altekruse, K.A. McGlynn, P.S. Rosenberg, J. Clin. Oncol. 34 (2016) 1787-1794. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2015.64.7412 |

| [3] |

R.L. Siegel, K.D. Miller, A. Jemal, CA Cancer J. Clin. 69 (2019) 7-34. DOI:10.3322/caac.21551 |

| [4] |

R.M. Cox, R.K. Plemper, Curr. Opin. Virol. 24 (2017) 105-114. DOI:10.1016/j.coviro.2017.05.004 |

| [5] |

J. Kalyanasundram, A. Hamid, K. Yusoff, S.L. Chia, Acta Trop. 183 (2018) 126-133. DOI:10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.04.007 |

| [6] |

V. Schirrmacher, Expert Opin, Biol. Ther. 15 (2015) 1757-1771. DOI:10.1517/14712598.2015.1088000 |

| [7] |

V. Schirrmacher, S. van Gool, W. Stuecker, Biomedicines 7 (2019) 66. DOI:10.3390/biomedicines7030066 |

| [8] |

Y. Sun, H. Zheng, S. Yu, et al., J. Virol. 93 (2019) e00322-19. DOI:10.1128/JVI.00322-19 |

| [9] |

X. Xu, C. Yi, X. Yang, et al., Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 14 (2019) 213-221. DOI:10.1016/j.omto.2019.06.001 |

| [10] |

G. Vijayakumar, S. McCroskery, P. Palese, J. Virol. 94 (2020) e01677-19. DOI:10.1128/JVI.01677-19 |

| [11] |

F.Y. Huang, J.Y. Wang, S.Z. Dai, et al., J. Immunother. Cancer 8 (2020) e000330. DOI:10.1136/jitc-2019-000330 |

| [12] |

Y. Zhang, Y. Zhang, Q. Guo, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11 (2019) 23018-23025. DOI:10.1021/acsami.9b06097 |

| [13] |

J.L. Au, B.Z. Yeung, M.G. Wientjes, Z. Lu, M.G. Wientjes, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 97 (2016) 280-301. DOI:10.1016/j.addr.2015.12.002 |

| [14] |

J. Wang, H. Wang, H. Cui, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 3143-3148. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.07.027 |

| [15] |

V.M. Moreno, E. Álvarez, I. Izquierdo-Barba, et al., Adv. Mater. Interfaces 7 (2020) 1901942. DOI:10.1002/admi.201901942 |

| [16] |

H. Shen, Q. Gao, Q. Ye, et al., Int. J. Nanomedicine 13 (2018) 7409-7426. DOI:10.2147/ijn.s178585 |

| [17] |

E. Smith, J. Breznik, B.D. Lichty, Hum. Gene Ther. 22 (2011) 1053-1060. DOI:10.1089/hum.2010.227 |

| [18] |

R. Strauss, A. Lieber, Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 11 (2009) 513-522. |

| [19] |

C. Kapoor, S. Vaidya, V. Wadhwan, G. Kaur, A. Pathak, J. Cancer Res. Ther. 12 (2016) 28-35. DOI:10.4103/0973-1482.157337 |

| [20] |

N. Cui, M. Hu, R.A. Khalil, Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 147 (2017) 1-73. |

| [21] |

A. Malara, D. Ligi, C.A. Di Buduo, F. Mannello, A. Balduini, Cells 7 (2018) 80. DOI:10.3390/cells7070080 |

| [22] |

K. Kessenbrock, V. Plaks, Z. Werb, Cell 141 (2010) 52-67. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015 |

| [23] |

A. Jabłońska-Trypuć, M. Matejczyk, S. Rosochacki, J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 31 (2016) 177-183. DOI:10.3109/14756366.2016.1161620 |

| [24] |

K.A. Hasty, J.J. Jeffrey, M.S. Hibbs, H.G. Welgus, J. Biol. Chem. 262 (1987) 10048-10052. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)61073-7 |

| [25] |

P.F. Yu, Y. Huang, Y.Y. Han, et al., Oncogene 36 (2017) 482-490. DOI:10.1038/onc.2016.217 |

| [26] |

K.H. Jung, I.K. Choi, H.S. Lee, et al., Cancer Lett. 396 (2017) 155-166. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2017.03.009 |

| [27] |

P. Sette, N. Amankulor, A. Li, et al., Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 15 (2019) 214-222. DOI:10.1016/j.omto.2019.10.005 |

| [28] |

J. Kiyokawa, Y. Kawamura, S.M. Ghouse, et al., Clin Cancer Res. 27 (2021) 889-902. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-20-2400 |

| [29] |

S. Schäfer, S. Weibel, U. Donat, et al., BMC Cancer 12 (2012) 366. DOI:10.1186/1471-2407-12-366 |

| [30] |

B.K. Jung, H.Y. Ko, H. Kang, et al., J. Immunother. Cancer 8 (2020) e000763. DOI:10.1136/jitc-2020-000763 |

| [31] |

Y. Li, J. Hong, B.K. Jung, E. Oh, C.O. Yun, Cancer Lett. 459 (2019) 15-29. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2019.05.033 |

| [32] |

B. Thaci, I.V. Ulasov, A.U. Ahmed, et al., Gene Ther. 20 (2013) 318-327. DOI:10.1038/gt.2012.42 |

| [33] |

S. Lavilla-Alonso, M.M. Bauer, U. Abo-Ramadan, et al., Cancer Gene Ther. 19 (2012) 126-134. DOI:10.1038/cgt.2011.76 |

| [34] |

A. Hamada, Y. Kita, K. Murakami, et al., J. Virol. Methods 279 (2020) 113854. DOI:10.1016/j.jviromet.2020.113854 |

| [35] |

L.C. Chandler, A.R. Barnard, S.L. Caddy, et al., Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 14 (2019) 77-89. DOI:10.1016/j.omtm.2019.05.012 |

| [36] |

J. Ge, X. Wang, L. Tao, et al., J. Virol. 85 (2011) 8241-8252. DOI:10.1128/JVI.00519-11 |

| [37] |

J. Ge, G. Deng, Z. Wen, et al., J. Virol. 81 (2007) 150-158. DOI:10.1128/JVI.01514-06 |

| [38] |

H.L. Kaufman, F.J. Kohlhapp, A. Zloza, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15 (2016) 660. DOI:10.1038/nrd.2016.178 |

| [39] |

J. Decock, S. Thirkettle, L. Wagstaff, D.R. Edwards, J. Cell Mol. Med. 15 (2011) 1254-1265. DOI:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01302.x |

| [40] |

P. Åström, K. Juurikka, E.S. Hadler-Olsen, et al., Br. J. Cancer 117 (2017) 1007-1016. DOI:10.1038/bjc.2017.249 |

| [41] |

M. Sarper, M.D. Allen, J. Gomm, et al., Breast Cancer Res. 19 (2017) 33. DOI:10.1186/s13058-017-0822-9 |

| [42] |

J. Decock, W. Hendrickx, S. Thirkettle, et al., Breast Cancer Res. 17 (2015) 38. DOI:10.1186/s13058-015-0545-8 |

| [43] |

D. Zamarin, R.B. Holmgaard, J. Ricca, et al., Nat. Commun. 8 (2017) 1434. DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-01484-6 |

2021, Vol. 32

2021, Vol. 32