b School of Petrochemical Engineering, Changzhou University, Changzhou 213164, China

Traditional tert-butyl calixarenes were synthesized from the condensation reaction of tert-butylpheonl and formaldehyde [1], leading to the formation of cyclic oligomers with different phenol units bridged by methylene groups. Calixarenes could be constructed by one-pot, stepwise, or fragment condensation synthetic strategies [1, 2]. A variety of calixarene derivatives have also been widely and well developed, and they are applied in molecular switches [3], multi-stimuli responsive gel [4], organocatalyst [5], catenane [6], cancer biomarker [7], heteromultivalent platform for peptide binding [8], electrodes [9], controlled drug delivery [10], and so on.

Similarly as calixarenes have the repeating phenol units bridged with methylene groups, the pillararenes that were firstly reported by Ogoshi [11] and Cao [12] have the repeating dimethylhydroquinone units bridged with methylene groups, and their development has also been paid a lot of attentions [13, 14]. Typically, such synthetic strategy based on the condensation reaction of alkylhydroquiones or their analogues and paraformaldehyde has been applied for the development of numberous novel macrocycles, such as helicarenes [15, 16], geminiarene [17], desymmetrized leaning pillar[6]arene [18], biphen[n]arenes [19, 20], terphen[n]arenes and quaterphen[n]arenes [21], tiara[5]arene [22], bowtiearene [23], belt[n]arenes [24, 25], asararenes [26], calix[4, 5]tetrolarenes [27], prismarenes [28] and pagoda[4]arene [29].

All of those macrocyclic arenes mentioned above contain the hydroxy-substituted aromatic rings bridged by methylene groups, and such unique structures play an important role in the supramolecular chemistry. In one of cases, with the hybridized structure of calixarenes and pillararenes (Scheme 1), the calixarenes skeleton with hydroquinone units bridged by methylene groups could be more interesting, due to its redox properties of hydroquinone units and easy modification at both up and lower rims as in pillararenre cases. For example, in 1997 the synthesis of p-(benzyloxy)calix[8]arene was reported [30] as a major product with 48% yield in one-pot synthetic procedure catalyzed by NaOH, while p-(benzyloxy)calix[6]- and [7]-arenes as minor products were obtained with 5.7% and 3.4% yields, respectively. And in their following work, RbOH [31] was used as a base to improve the synthetic yield of p-(benzyloxy)calix[6]arene with the 40% yield. The benzyl groups of such calixarene are good protecting groups for phenol functional groups, but the big size of benzyl groups may not be good for the host-guest interactions. Additionally, the synthesis of p-(methoxy)calix[7]arene (17) was reported [32] in 2014 without the given yield, but its exact structure was not clearly confirmed, where the structure of seven repeating units was only investigated by MS spectrum, and its 1H NMR spectrum of " pure 17" obviously showed it was the mixture of compounds. Moreover, the synthesis of p-(methoxy)calix[6]arene (16) was also reported [33], but it was incorrectly claimed to be 16, after we carefully checked its 1H NMR spectrum data as well as its permethylated derivative, which did not match the reported spectrum data of 16 [34].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Previous synthetic work of 26 and 28, and the synthetic route of 26, 27 and 28 in this work. All the above yields are separation yields. | |

Besides the unclear one-pot synthesis of such hybridized structure above, the previously traditional synthesis of 16 and p-(methoxy)calix[8]arene (18) could be step wisely conducted, in which the introduction of OH groups at the upper rim of the calixarene skeleton was obtained by exploiting a Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of a suitable p-acetyl precursor from tert-butylcalixarenes (Scheme 1) [34]. At present, it is still a big challenge to prepare 16, 17 or 18 calixarenes clearly and directly by one step from p-methoxyphenol and separated them, as well as correctly and accurately characterize them. Herein, we report the facile preparation of 16, 17 or 18 from p-methoxyphenol and paraformaldehyde catalyzed by t-BuONa in the aromatic solvent (Scheme 1), and the separation of 17 and 18 with column chromatography free. Furthermore, the resulting 16, 17 or 18 could be easily methylated to give permethylated p-(dimethyloxy)calix[6, 7 or 8]arenes 26, 27 or 28, and the host-guest interaction between 26 and methyl-4, 4′-bipyridinium hexafluorophosphate (MV+) was also investigated in organic solvents.

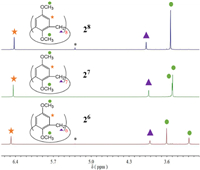

To synthesis p-(methoxy)calix[n]arenes (n = 6, 7, 8), initially, p-methoxyphenol reacted with paraformaldehyde in o-xylene catalyzed by t-BuONa. During the reaction, the orange precipitate was obtained. It was found that the resulting precipitate mixture could be the mixture of three possible calixarene compounds based on its 1H NMR spectrum (Fig. 1a), which showed three sets of signals at 6.65, 6.63 and 6.56 ppm, respectively, corresponding to the benzene units of calixarene, one peak at 3.75 ppm corresponding to the bridged methylene groups, and two peaks at 3.62 and 3.57 ppm corresponding to the methoxy groups. Additionally, based on the integration ratio of proton peaks of above benzene units, the molar ratio of such three calixarene products is approximately 2:1:5, which indicated the formation of three kind of calixarene compounds with different number of monomers.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. 1H NMR spectra (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K) of (a) 16, 17 and 18 mixtures and (b) 26, 27 and 28 mixtures. | |

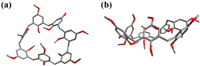

In order to confirm the structures of the above three kind of possible calixarene compounds, they would be analyzed after complete methylation with CH3I, since they were not well soluble in the most common organic solvents and the mixture compounds were very polar, which makes their column purification impossible. After methylation, the 1H NMR spectrum of fully methylated mixture products also showed three sets of signals, further indicating that there might be three calixarene compounds formed (Fig. 1b), and additionally, the silicone gel thin layer chromatography (TLC) also showed three obvious separated spots on TLC plate (petroleum ether: ethyl acetate = 2:1). Then the fully methylated mixture products were successfully separated by column chromatography to obtain three pure calixarene compounds, respectively, and they were then all identified as fully methylated calixarenes by 1H NMR, 13C NMR and HR-ESI-MS, which were confirmed to be 26, 27 and 28, respectively. According to the 1H NMR spectra of the mixture after methylation, the product molar ratio of these three mixtures was 2:1:5 (Fig. 1b), corresponding to the ratio of the reaction mixture before methylation reaction (Fig. 1a). Moreover, the obtained spectra of 26 and 28 were completely in accordance with previously reported one [33, 34]. However, 27 was a new calixarene compound that has not been reported, and its 1H NMR, 13C NMR spectra, and HR-ESI-MS was shown in Figs. S10–S12 (Supporting information). Fortunately, the single crystal of 27 was successfully obtained by slow evaporation of a mixed solvent of ethyl acetate and light petroleum. To the best of our knowledge, the single crystal structures of calix[7]arene derivatives have been rarely reported [35]. From its single crystal structure, the structure of 27 with seven repeating units was confirmed, and it can be seen that 27 has a deformed cavity (Fig. 2). The distance between carbon atoms on the farthest methylene group is 11.4 Å, the angle range between two adjacent benzene rings connected by methylene is 110.3°–115.4°, compared with the angle presented by the normal sp3 hybridization, and 27 shows a certain degree of flexibility.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) Top view and (b) side view of crystal structure of 27. | |

As shown in Fig. 3, the pure 1H NMR spectra of the methylated three calixarenes, 26, 27 and 28, were interestingly and obviously different from each other. From 26 to 28, the chemical shifts of the protons on the benzene ring shifted to a little higher field, and the protons on the methylene group shifted to a little lower field. With the enlargement of the cavity, the chemical shifts of two methoxy groups in the upper and lower edges of calixarene were closer and closer in 1H NMR spectra from 26 to 28, and two methoxy peaks of 28 were completely merged into a single peak (Fig. 3) different from the obvious separation of signals in 26. This may be due to the increasing degree of deformation of the calixarene as the size of cavity increases, and the flipping speed of benzene units is accelerated.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Comparison of pure 26, 27 and 28 by 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K). * Represents the solvent peak of dichloromethane. | |

As a result, three fully methylated 26, 27 and 28 were clearly separated and identified, and in order to further determine their original structures of 16, 17 and 18, a solvent extraction and purification method for 16, 17 and 18 was tried, avoiding their separation problem by column chromatography. After the solubility of the mixture of calixarene products 16, 17 and 18 obtained from the first step was tested in various solvents, an optimal solvent purification process was found (Scheme 2). First, the p-methoxycalixarene crude reaction mixture was dissolved in hot pyridine and then hot filtration was conducted, leading to quite pure 18 in 53% yield, whose structure was confirmed by its methylated structure after its methylation. Then the remaining filtrate was evaporated, and the resulting solid obtained was dissolved in hot dichloromethane and then the hot filtration was conducted. At this time, the precipitate filtered out was major 18 with a small amount of 17 (17: 18 = 1:8, molar ratio), and the remaining filtrate was turned out to contain the major 16 with small amount of 17 after the investigation of their NMR spectra. Finally, the resulting solid evaporated from the above remaining filtrate was dissolved in dichloromethane, and the filtration was conducted at room temperature. After filtration, the small amount of 17 could be removed to obtain a pure 16 solid in 12% yield, whose structure was confirmed by its methylated structure after its methylation. The resulting filtrate contained major 16 with minor 17 (17: 16 = 1:3, molar ratio). Furthermore, the pure 18 and 16 were methylated, respectively, and then washed with methanol to give the pure methylated products 28 and 26, avoiding the column chromatography.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. The solvent purification procedure for the calixarene mixture. | |

Consequently, as discussed above, based on the integration of the proton signals of benzene ring of 16, 17 and 18 in the 1H NMR spectrum of the mixture directly from the reaction, and the molar ratio among 16, 17 and 18 can be determined. In the benzene ring region, the yellow hexagon is from 16, the green circle is from 1, and the blue pentagon is from 18 (Fig. 1a). This strategy provided us the quick method for the identification of molar ratio of 16, 17 and 18 in the mixture. For the following reactions to optimize, different alkaline catalysts and solvents were tried in various reactions to study the distribution of 16, 17 and 18 in the mixture. Using different alkaline catalysts, such as t-BuOLi, t-BuONa and t-BuOK, to react in the same solvent, o-xylene will result in different distributions of products (entries 1–3, Table 1). It could be caused by the different size of Li+, Na+ or K+, because those metal ions play an important role of template agent in the formation of calixarene macrocycles. The same distribution of the product was obtained with the same alkaline catalyst, t-BuOK, in xylene or o-xylene (entries 3 and 4, Table 1), but the distribution of the products obtained in hydrogenated naphthalene is significantly different (entry 5, Table 1). The optimal reaction condition (entry 2, Table 1) for the synthesis of 16 was found, where the molar ratio of the products of 16, 17 and 18 is approximately 2:1:5.

|

|

Table 1 Investigation of the reaction conditions. |

In principle, the cavity of calixarene could be able to host different kind of organic guests leading to interesting potential applications. Among three fully methylated 26, 27 and 28 has a more suitable size of cavity for the host-guest research. It was interesting to find that 26 showed a potentially good host-guest interaction with MV+ in CDCl3/CD3CN (1:1, v/v), which was initially studied by 1H NMR experiment. All the guest signal of MV+ in the 1H NMR spectrum (Fig. S16 in Supporting information) showed the obvious upfield shifts upon addition of 26, and the chemical shifts of protons on pyridine moiety were a little greater than that on methylpyridine moiety, which implied that the pyridine moiety of MV+ more possibly threaded into the pocket of 26. However, because the solubility of 26 in such organic solvents is not so good, as well as guest molecular MV, 1H NMR titration and Job plot experiments were difficult to conduct to measure their host-guest interaction. Therefore, UV–vis absorption spectrometry was selected to study their host-guest interaction. UV–vis absorption spectra of titration experiment of 2 with MV+ is shown in Fig. S18 (Supporting information), which indicated that the peak at 284 nm of 2 was decreasing upon addition of MV+. Job plot experiments based on UV–vis absorption spectra were conducted, which showed that 26 was complexed with MV+ at a stoichiometric ratio of 1:1, and the association constant (Ka) between 26 and MV+ was calculated to be (4.21 ± 0.73) × 103 L/mol.

In summary, we have reported a facile synthetic method under basic catalytic condition to prepare p-methoxycalixarene, 16, 17 and 18, in one single step starting from p-methoxyphenol. In comparison with the previously reported method, this procedure was more efficient and easier to handle. The pure 16 and 18 could be separated by solvent extraction from the mixture and their structures were confirmed. Furthermore, the fully methylated derivatives 26, 27 and 28 were synthesized as well, and the structure of 27 was confirmed by its single crystal structure. Finally, the host-guest interaction between 26 and MV+ was studied in organic solvents. The results reported in this paper represent an interesting and efficient method to construct calixarene family derivatives, and more host-guest interactions and their self-assembly properties are in development in our lab.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare no competing financial interest.

AcknowledgmentThis work was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22071104, 21871136).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.05.045.

| [1] |

V. Böhmer, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 34 (1995) 713-745. DOI:10.1002/anie.199507131 |

| [2] |

B.Q. Hong, F.F. Yang, H.Y. Guo, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 20 (2009) 1039-1041. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2009.04.008 |

| [3] |

G.G. Pognon, C. Boudon, K.J. Schenk, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (2006) 3488-3489. DOI:10.1021/ja058132l |

| [4] |

K.P. Wang, Y. Chen, Y. Liu, Chem. Commun. 51 (2015) 1647-1649. DOI:10.1039/C4CC08721F |

| [5] |

Z.X. Xu, G.K. Li, C.F. Chen, Z.T. Huang, Tetrahedron 64 (2008) 8668-8675. DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2008.07.001 |

| [6] |

Z.T. Li, X.L. Zhang, X.D. Lian, et al., J. Org. Chem. 65 (2000) 5136-5142. DOI:10.1021/jo000196l |

| [7] |

Z. Zheng, W.C. Geng, J. Gao, et al., Chem. Sci. 9 (2018) 2087-2091. DOI:10.1039/c7sc04989g |

| [8] |

Z. Xu, S. Jia, W. Wang, et al., Nat. Chem. 11 (2019) 86-93. DOI:10.1038/s41557-018-0164-y |

| [9] |

Q. Zhao, W. Huang, Z. Luo, et al., Sci. Adv. 4 (2018) eaao1761. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.aao1761 |

| [10] |

Y. Zhou, H. Li, Y.W. Yang, Chin. Chem. Lett. 26 (2015) 825-828. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2015.01.038 |

| [11] |

T. Ogoshi, S. Kanai, S. Fujinami, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (2008) 5022-5023. DOI:10.1021/ja711260m |

| [12] |

D. Cao, Y. Kou, J. Liang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48 (2009) 9721-9723. DOI:10.1002/anie.200904765 |

| [13] |

K. Jie, Y. Zhou, E. Li, F. Huang, Acc. Chem. Res 51 (2018) 2064-2072. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00255 |

| [14] |

T. Xiao, W. Zhong, L. Zhou, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 30 (2019) 31-36. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2018.05.034 |

| [15] |

G.W. Zhang, P.F. Li, Z. Meng, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55 (2016) 5304-5308. DOI:10.1002/anie.201600911 |

| [16] |

C.F. Chen, Y. Han, Acc. Chem. Res. 51 (2018) 2093-2106. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00268 |

| [17] |

J.R. Wu, Y.W. Yang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 12280-12287. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b03559 |

| [18] |

J.R. Wu, A.U. Mu, B. Li, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 9853-9858. DOI:10.1002/anie.201805980 |

| [19] |

H. Chen, J. Fan, X. Hu, et al., Chem. Sci. 6 (2015) 197-202. DOI:10.1039/C4SC02422B |

| [20] |

L. Dai, Z.J. Ding, L. Cui, et al., Chem. Commun. 53 (2017) 12096-12099. DOI:10.1039/C7CC06767D |

| [21] |

B. Li, B. Wang, X. Huang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 3885-3889. DOI:10.1002/anie.201813972 |

| [22] |

W. Yang, K. Samanta, X. Wan, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 3994-3999. DOI:10.1002/anie.201913055 |

| [23] |

S.N. Lei, H. Xiao, Y. Zeng, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 10059-10065. DOI:10.1002/anie.201913340 |

| [24] |

T.H. Shi, Q.H. Guo, S. Tong, M.X. Wang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 4576-4580. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c00112 |

| [25] |

Q. Zhang, Y.E. Zhang, S. Tong, M.X. Wang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 1196-1199. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b12181 |

| [26] |

S.T. Schneebeli, C. Cheng, K.J. Hartlieb, et al., Chem. Eur. J. 19 (2013) 3860-3868. DOI:10.1002/chem.201204097 |

| [27] |

Y. Zafrani, Y. Cohen, Org. Lett. 19 (2017) 3719-3722. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01511 |

| [28] |

P. Della Sala, R. Del Regno, C. Talotta, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 1752-1756. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b12216 |

| [29] |

X.N. Han, Y. Han, C.F. Chen, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 8262-8269. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c00624 |

| [30] |

A. Casnati, R. Ferdani, A. Pochini, R. Ungaro, J. Org. Chem. 62 (1997) 6236-6239. DOI:10.1021/jo970620r |

| [31] |

V. Huc, V. Guérineau, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010 (2010) 2199-2205. DOI:10.1002/ejoc.200901281 |

| [32] |

R. Zhou, S. Teo, M.P. Srinivasan, Thin Solid Films 550 (2014) 210-219. DOI:10.1016/j.tsf.2013.10.161 |

| [33] |

T.A. Yamagishi, E. Moriyama, G.I. Konishi, Y. Nakamoto, Macromolecules 38 (2005) 6871-6875. DOI:10.1021/ma0478299 |

| [34] |

M. Mascal, R. Warmuth, R.T. Naven, et al., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 (1999) 3435-3441. |

| [35] |

P. Thuéry, M. Nierlich, B. Souley, et al., J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. (1999) 2589-2594. |

2021, Vol. 32

2021, Vol. 32