b Key Laboratory of Combinatorial Biosynthesis and Drug Discovery (MOE), Hubei Province Engineering and Technology Research Center for Fluorinated Pharmaceuticals, Wuhan University School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Wuhan 430071, China;

c Center for Animal Experiment, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430071, China;

d Shenzhen Institute of Wuhan University, Shenzhen 518057, China

Gastric ulcers, chronic ulcers which occur frequently in the gastric antrum, gastric horn, and cardia, are considered to be one of the most common and multiple diseases worldwide [1, 2]. Factors like Helicobacter pylori (Hp), gastric acid and pepsin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), etc., would cause gastric mucosal damage, resulting in weakened barrier function and leading to the formation of gastric ulcers [3-5]. To diagnose gastric ulcers, endoscopes and X-rays are currently used in clinical practice. However, these techniques are either invasive or radioactive hazard, or highly depending on the experience of the manipulator [4, 6]. Furthermore, considering the pathological characteristics such as recurrence, long pathological period and complicated complications, many tests and evaluations are often required during the diagnosis and treatment process [6, 7]. Therefore, a non-invasive, non-radiation accurate diagnostic technique for gastric ulcers is highly demanded. As an important indicator of clinical gastric function, gastric emptying time can provide valuable information for diagnosis and treatment of diseases [8-10]. Inflammation congestion, edema, scar tissue formation, and pyloric obstruction caused by gastric ulcers would lead to delayed gastric emptying [8], thus making it possible to establish the relationship between gastric emptying and gastric ulcers for further diagnosis [9-11]. Bioadhesive materials such as sucralfate [12, 13], polyacrylic acid, cyclodextrin, cellulose and their derivatives can form viscous colloid, and exhibit long retention time in gastric ulcer sites [14-17], providing an ideal platform to distinguish gastric ulcers from healthy ones. Kazuki Sada et al. synthesized uniform cubic gel particles (CGPs) with well-defined polyhedral shapes using cross-linked cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks (CL-CD-MOF) [18]. CGPs could provide mesoscopic building blocks with a soft interface for biomedical applications. These characters make CL-CD-MOF an attractive platform to prepare gastric ulcer imaging agents.

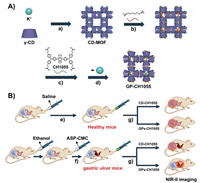

In vivo fluorescence imaging in the second near-infrared bio-transparent window (NIR-II, 1000–1700 nm) is an emerging technique with minimized tissue auto-fluorescence and light scattering, and deeper tissue penetration at longer wavelengths [19-29], that can noninvasively detect and monitor the physiological or pathological processes in vivo at the cellular and molecular level in real-time [30-36]. Thus far, various types of NIR-II inorganic materials [37-39], polymeric nanostructures [40-42] and small-molecule fluorophores [43-48] have been reported. The first NIR-II small-molecule fluorophore CH1055 in 2015 has been built up from benzo-bis (1, 2, 5-thiadiazole) (BBTD) for in vivo imaging [49]. By changing functional groups of CH1055, the resulting dye CH-4 T produced a brilliant 110-fold increase in NIR-II fluorescence, when mixed with plasma proteins in the blood, spontaneously forms brightly fluorescent supramolecular assemblies [50]. However, no research based on small-molecule NIR-II imaging technology has been reported for in vivo detecting detailed pathological changes of gastric ulcers. Herein, we synthesized a novel fluorophores GPs-CH1055 by covalently bonding CH1055 to CL-CD-MOF for gastric ulcer NIR-II imaging (Scheme 1A). GPs-CH1055 gel particles possess high biocompatibility, and have strong stability in different media and pH buffers. Subsequently, in vivo studies were carried out to validate the retention efficiency of GPs-CH1055 gel particles. GPs-CH1055 showed longer residence time in gastric ulcer mice than that in healthy mice, while no significant difference was observed in the control group (Scheme 1B). Besides, GPs-CH1055 was completely excreted from the gastrointestinal tract. Therefore, GPs-CH1055 gel particles could serve as in vivo NIR-II fluorophores for non-invasive gastrointestinal imaging and gastric ulcer diagnosis.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Scheme illustration of the preparation of GP-CH1055 and the gastric retention test. (A) Synthetic diagram of GPs-CH1055. a) Crystallization, b) cross-linking reaction, c) esterification reaction, d) removal of coordinated metal ions. (B) Schematic diagram of gastric retention experiment. e) The mice in the control group were given saline, f) Ethanol and aspirin were used to establish gastric ulcer model, g) CD-CH1055 / GPs-CH1055 was given by gavage. The NIR-II imaging was performed at the same time. | |

Serving as a platform, cuboidal CD-MOF was simply prepared by reacting γ-CD with KOH in aqueous solution, and crystallized by the regular diffusion method of methanol [49, 51]. The γ-CDs in CD-MOF were then cross-linked with ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether (L) to synthesize CL-CD-MOF. In order to real-time monitor the movement of CL-CD-MOF in the gastrointestinal tract, a NIR-II small molecule CH1055 with four carboxyl was covalently conjugated to CL-CD-MOF via the ester bond. The unreacted L and potassium ions were removed by soaking CL-CD-MOF in the mixed solvent (EtOH/H2O = 1:1 (v/v)) to afford GPs-CH1055 particles. Moreover, CD-CH1055 was synthesized using the amide reaction of CH1055 to mono-6-O-NH2-β-CD as a contrast.

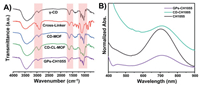

The morphology of CD-MOFs was characterized by transmission electron microscope (TEM), which showed that CD-MOFs were well-defined crystals with a diameter of approximately 200 nm (Fig. S1 in Supporting information). To confirm the cross-linking reaction between L and γ-CD, and verify the modification of CH1055, infrared (IR) spectroscopy and UV absorption spectra were adopted. As shown in the IR spectra (Fig. 1A), the stretching band (2880−2920 cm−1) attributes to the stretching vibration of methylene groups in L. Compared with the sharp peak derives from the C-O-C stretching vibration (1020–1160 cm−1) in free γ-CD, a broad band is observed in immobilized γ-CD due to the cross-linking. These changes confirmed that L successfully served as cross-linkers between γ-CDs to form CL-CD-MOF. Furthermore, UV absorption spectra of GPs-CH1055 were emerged a characteristic absorption peak of CH1055 at 714 nm (Fig. 1B), indicating that CL-CD-MOF was modified with CH1055. The UV spectra also showed that CH1055 was conjugated to the mono-6-O-NH2-β-CD, and CD-CH1055 was further characterized by MALDI-TOF-MS (Fig. S2 in Supporting information).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Characterization of CD-MOFs and GPs-CH1055 particles. (A) FT-IR spectra of γ-CD, ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether (cross-linker), CL-CD-MOF. (B) UV–vis-NIR absorption spectra of CH1055, GPs-CH1055, CD-CH1055 particles in aqueous solution. | |

To assess the photo-stability, GPs-CH1055, CD-CH1055 and ICG were dispersed in water respectively, and were exposed to continuous 808 nm laser irradiation for 2 h at a power density of 180 mW/cm2. The fluorescence intensity of ICG showed a drastic decrease while GPs-CH1055 and CD-CH1055 maintained a stable fluorescence intensity (Fig. 2A, Fig. S3 in Supporting information), demonstrating the superior photo-stability of the as-prepared materials. Moreover, GPs-CH1055 and CD-CH1055 were incubated in water, PBS, and FBS for 2 h, and no significant fluorescent changes were observed at different times points (Fig. 2B, Fig. S4 in Supporting information). Subsequently, the fluorescent intensity of GPs-CH1055 and CD-CH1055 distributed at different pH buffers ranging from 1 to 9 was sustained at different time points (10 min, 1 h, 24 h) (Fig. 2C, Fig. S5 in Supporting information). The in vitro imaging of GPs-CH1055 and CD-CH1055 were also acquired using an InGaAs camera under 808 nm laser excitation with various long-pass (LP) filters (880 nm, 1000 nm, 1250 nm, 1320 nm and 1550 nm). Intensive fluorescence of GPs-CH1055 and CD-CH1055 can be visualized under 880 nm and 1000 nm LP filters with a short exposure time of 30 ms (Fig. 2E), thus paving the way for in vivo NIR-II imaging.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. The in vitro NIR-II fluorescence property and stability of GPs-CH1055 and CD-CH1055. (A) Photo-stability study of GPs-CH1055 and CD-CH1055 in aqueous solution (ICG as reference, under continuous 808 nm laser (180 mW/cm2) irradiation for 120 min). (B) The fluorescence intensity values of GPs-CH1055 in aqueous solution, PBS and FBS after 1 h and 2 h incubation. (C) pH-Stability study of GPs-CH1055 and CD-CH1055 at different pH buffers, the fluorescence intensity was measured after 10 min, 1 h, 24 h incubation. (D) Cell viability of 4T1 and MDCK cells after incubation with different concentrations of the GPs-CH1055 NPs for 24 h (n = 3). (E) NIR-II images of GPs-CH1055 (left) and CD-CH1055 (right) NPs in aqueous solution with different LP filters (LP880, LP1000, LP1250, LP1320, LP1550 from left to right, exposure time: 30 ms). | |

Furthermore, as a gastrointestinal tract imaging agent, GPs-CH1055 was supposed to be completely expelled instead of being assimilated. To test this property, GPs-CH1055 gel particles were given to the healthy mice by gavage, followed by using NIR-II imaging to monitor the biodistribution of GPs-CH1055. It was found that 36 h later, NIR-II signals were diminished in the gastrointestinal tract (Fig. S6 in Supporting information) Then main organs of these mice were excised for further examination. As shown in Fig. S7 (Supporting information), no NIR-II fluorescence signals were observed in all of the organs. All these results indicated that GPs-CH1055 was completely expelled without being absorbed, and can be a stable NIR-II imaging agent in stomach for long-term monitoring.

The cytotoxicity of GPs-CH1055 and CD-CH1055 to 4T1 mammary cancer and MDCK canine kidney cell lines were evaluated by the standard 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. As shown in Fig. 2D, the cell viability remained ~100% even at the concentration of GPs-CH1055 up to 3.52 mg/mL, and no obvious changes were observed in CD-CH1055 either (Fig. S8 in Supporting information), indicating the superior bio-compatibility of these bioactive materials.

A chronic gastric ulcer animal model induced by ethanol-aspirin was established. As one of the most representative NSAIDs, aspirin can not only suppress the activity of COX-2 to reduce inflammation, but also inhibit COX-1 activity, resulting in insufficient synthesis of physiological prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in the gastrointestinal mucosa, which eventually lead to gastric mucosa damage [52-54]. Thus, ethanol (100 μL/20 g) was initially gavage to ICR mice (n = 10) followed by gavaging aspirin (200 mg/kg). Then aspirin was continuously given in the following 4 d to aggravate the symptoms of gastric ulcer caused by ethanol, and postpone the healing process to form chronic gastric ulcer mice models [55-58]. To verify whether the gastric ulcer models were successfully established, mice (n = 3) were randomly sacrificed. We excised the stomach and cut along the great curvature of the stomach to eversion the gastric mucosa, at the same time, the stomach of an untreated ICR mouse was also excised as the control. As shown in optical images, an obvious ulcer site accompanied by tissue erosion was observed at the antrum of the ethanol-aspirin treated group, while the gastric mucosa of the control group remained intact (Fig. S9 in Supporting information). Furthermore, the gastric mucosa was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E). Histological analysis of the ulcer site at different magnification showed exudate and necrotic tissues on the surface of the mucosa, and infiltration of inflammatory cells. Furthermore, vacuoles, nuclear shrinkage, cell rupture were found in the glandular cells surrounding the ulcer (Figs. 3A and B). These data further verified the successful establishment of gastric ulcer models.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. The verification of gastric ulcer models and in vivo NIR-II imaging of GPs-CH1055. (A, B) Hematoxylin and eosin stained images of mucosal tissues of gastric antrum from (A) the control mice and (B) gastric ulcer mice at different multiples (scale bar: 200 μm, 100 μm, 50 μm). Representative NIR-II images of (C) gastric ulcer mouse and (D) healthy mouse at different time points (1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 24 h) after intragastric administrating of GPs-CH1055 gel particles (200 μL/20 g) under 808 nm excitation (1000LP and 100 ms). | |

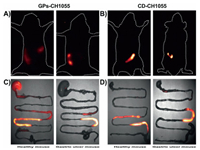

Motivated by the superior NIR-II imaging performance and stability in stomach, GPs-CH1055 was further applied to aspirin-ethanol-induced gastric ulcer mice for non-invasive NIR-II imaging [59]. We initially tracked GPs-CH1055 gel particles in the gastrointestinal tract of gastric ulcer mice and healthy mice. It was found that 1 h post-intragastric administration, a considerable portion of GPs-CH1055 in the gastric ulcer mouse remained in the stomach, and had significant retention effects in gastric ulcer mice, while GPs-CH1055 was completely cleared out the stomach in healthy mice, and entered into small intestine (Figs. 3C and D). As comparison, CD-CH1055 was specifically synthesized by conjugating CH1055 to mono-6-O-NH2-β-CD. As shown in Fig. 4, gastric ulcer mice (n = 3 per group) and untreated ICR mice (n = 3 per group) were intravenously injected with GPs-CH1055 (0.2 mg)/CD-CH1055 (0.2 mg), and imaged at 30 min post-injection. It was observed GPs-CH1055 had a longer retention time in the gastric ulcer mice (Fig. 4A), while no significant fluorescence signals were observed in the stomach area of gastric ulcer mice dosed with CD-CH1055 (Fig. 4B). Subsequently, the intact gastrointestinal tract was excised in 1 h for further analysis. Very strong fluorescence signals from GPs-CH1055 were detected in the ulcerated stomach. However, no obvious fluorescence signals were observed in the stomach of healthy mice and gastric ulcer mice treated with GPs-CH1055/CD-CH1055, CD-CH1055 respectively (Figs. 4C and D). These results further proved that GPs-CH1055 can be specifically retained in the gastric ulcer sites, and can be used for gastric ulcer imaging and diagnosis.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. The in vivo NIR-II Fluorescence imaging of healthy/gastric ulcer mice. (A and B) Representative NIR-II images of the gastrointestinal tract in healthy mice (left) and gastric ulcer mice (right) 30 min after gavage with GPs-CH1055 (A) and CD-CH1055 (B). (C and D) Corresponding ex vivo NIR-II fluorescence images of gastrointestinal tract 1 h after gavage. | |

In summary, we have successfully designed and synthesized a NIR-II fluorophore with superior medium stability and high performance for gastric ulcer dynamic NIR-II imaging and diagnosis. By covalently linking a NIR-II small-molecule dye CH1055 to CL-CD-MOF, the conjugate GPs-CH1055 can realize in real-time observation of gastrointestinal conditions. To the best of our knowledge, as a proof-of-concept, this is the first time that non-invasive and real-time NIR-II imaging of gastric ulcers in health and in disease has been performed. Besides, GPs-CH1055 has excellent biosafety and significant retention effects on gastric ulcer sites, which enables it to distinguish gastric ulcer ones from healthy ones. Further in vivo side-by-side comparison by the treatment of GPs-CH1055 and CD-CH1055, confirmed the specifically retention effect of GPs-CH1055 gel particles in the feature of the pathological changes of gastric ulcers. GPs-CH1055 holds great promise for noninvasive gastric ulcer imaging and diagnosis in the future.

Ethics statementAll animal experiments were approved by the Chinese Regulations for the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Wuhan University.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was partially supported by the National Key R & D Program of China (No. 2020YFA0908800), National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 81773674), Shenzhen Science and Technology Research Grant (No. JCYJ20190808152019182), Hubei Province Scientific and Technical Innovation Key Project (No. 2020BAB058), the Applied Basic Research Program of Wuhan Municipal Bureau of Science and Technology (No. 2019020701011429), the Local Development Funds of Science and Technology Department of Tibet (No. XZ202001YD0028C), Tibet Autonomous Region Science and Technology Plan Project Key Project (No. XZ201901-GB-11), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei (No. 2019CFB679), the Health Commission of Hubei Province Scientific Research Project (No. WJ2021Q031) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. ZNJC201931).

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2021.03.075.

| [1] |

J. Katz, B. Gonzalez, C.A. Cupula, et al., Acta Gastroenterol. Latinoam. 24 (1997) 253-257. |

| [2] |

M. Kuro-o, Y. Matsumura, H. Aizawa, et al., Nature 390 (1997) 45-51. DOI:10.1038/36285 |

| [3] |

I. Thung, S.E. Crowe, M.A. Valasek, et al., Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 43 (2016) 1249-1250. DOI:10.1111/apt.13625 |

| [4] |

G.F.P. de Souza, P. Taladriz-Blanco, L.A. Velloso, M.G. de Oliveira, et al., Molecules 20 (2015) 4109-4123. DOI:10.3390/molecules20034109 |

| [5] |

S.O. Sue, D.M. Dawson, J.A. Brown, D.R. Wood, C.S. Kleoudiset, Clin. Ther. 18 (1996) 1175-1183. DOI:10.1016/S0149-2918(96)80072-5 |

| [6] |

L. Laine, K. Takeuchi, A. Tarnawski, Gastroenterology 135 (2008) 41-60. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.030 |

| [7] |

K. Satoh, J. Yoshino, T. Akamatsu, et al., J. Gastroenterol. 51 (2016) 177-194. DOI:10.1007/s00535-016-1166-4 |

| [8] |

T. Takahashi, J. Gastroenterol. 38 (2003) 421-430. DOI:10.1007/s00535-003-1094-y |

| [9] |

P. Jr Engler-Pinto, J. Gama-Rodrigues, F.P. Lopasso, A.C. Cordeiro, H.W. Pinotti, Rev. Hosp. Clin. Fac. Med. Sao Paulo 50 (1995) 320-325. |

| [10] |

G. Jonderko, K. Jonderko, T. Golab, Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 84 (1990) 357-362. |

| [11] |

A. Tsukamoto, K. Ohno, S. Maeda, et al., J. Vet. Med. Sci. 74 (2012) 1103-1108. DOI:10.1292/jvms.12-0066 |

| [12] |

D. Hollander, A. Tarnawski, Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 173 (1990) 1-5. DOI:10.3109/00365529009091917 |

| [13] |

S. Nakazawa, R. Nagashima, I.M. Samloff, Digest. Dis. Sci. 26 (1981) 297-300. DOI:10.1007/BF01308368 |

| [14] |

M.K. Tolbert, Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 51 (2021) 33-41. DOI:10.1016/j.cvsm.2020.09.001 |

| [15] |

R.M. Yusif, I.I.A. Hashim, E.A. Mohamed, F.A. Badria, AAPS PharmSciTech 17 (2016) 328-338. DOI:10.1208/s12249-015-0351-8 |

| [16] |

Y. Jiao, X. Pang, M. Liu, et al., Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces 140 (2016) 361-372. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.12.049 |

| [17] |

E.P. Barros, S. Souza, M.V. Lins, et al., Life Sci. 265 (2021) 118742. DOI:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118742 |

| [18] |

Y. Furukawa, T. Ishiwata, K. Sugikawa, K. Kokado, K. Sada, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51 (2012) 10566-10569. DOI:10.1002/anie.201204919 |

| [19] |

M. Zhao, B. Li, H. Zhang, F. Zhang, Chem. Sci. 12 (2021) 3448-3459. DOI:10.1039/d0sc04789a |

| [20] |

X. Luo, Y. Yang, X. Qian, Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 2877-2883. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.07.009 |

| [21] |

S. He, J. Song, J. Qu, Z. Cheng, Chem. Soc. Rev. 47 (2018) 4258-4278. DOI:10.1039/C8CS00234G |

| [22] |

S. Zhang, H. Li, Q. Yao, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 2913-2916. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.01.006 |

| [23] |

Y. Xu, C. Li, R. Xu, et al., Chem. Sci. 11 (2020) 8157-8166. DOI:10.1039/d0sc03160g |

| [24] |

L. Tu, Y. Xu, Q. Ouyang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 30 (2019) 1731-1737. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2019.05.022 |

| [25] |

H. Pan, S. Li, J. Kan, Chem. Sci. 10 (2019) 8246-8252. DOI:10.1039/c9sc02674f |

| [26] |

R. Han, J. Peng, Y. Xiao, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 1717-1728. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.03.038 |

| [27] |

S. Liu, Y. Li, R.T.K. Kwok, et al., Chem. Sci. 12 (2021) 3427-3436. DOI:10.1039/d0sc02911d |

| [28] |

J. Li, Y. Liu, Y. Xu, et al., Coord. Chem. Rev. 415 (2020) 213318. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213318 |

| [29] |

Y. Sun, F. Ding, Z. Chen, et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116 (2019) 16729-16735. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1908761116 |

| [30] |

Y. Zhang, H. Teng, Y. Gao, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 2917-2920. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.03.020 |

| [31] |

J. Lin, Q. Li, X. Zeng, et al., Sci. China Chem. 63 (2020) 766-770. DOI:10.1007/s11426-019-9685-6 |

| [32] |

J. Yang, X. Hong, Sci. China Chem. 62 (2019) 7-8. DOI:10.1007/s11426-018-9341-7 |

| [33] |

H. Zhou, Y. Xiao, X. Hong, Chin. Chem. Lett. 29 (2018) 1425-1428. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2018.08.009 |

| [34] |

H. Zhou, S. Li, X. Zeng, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 1382-1386. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.04.030 |

| [35] |

R. Zhang, Z. Wang, L. Xu, et al., Anal. Chem. 91 (2019) 12476-12483. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.9b03152 |

| [36] |

Y. Xu, Y. Zhang, J. Li, et al., Biomaterials 259 (2020) 120315. DOI:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120315 |

| [37] |

X. Lei, R. Li, D. Tu, et al., Chem. Sci. 9 (2018) 4682-4688. DOI:10.1039/c8sc00927a |

| [38] |

F. Ren, H. Liu, H. Zhang, et al., Nano Today 34 (2020) 100905. DOI:10.1016/j.nantod.2020.100905 |

| [39] |

U. Rocha, K.U. Kumar, C. Jacinto, et al., Small 10 (2014) 1141-1154. DOI:10.1002/smll.201301716 |

| [40] |

Y. Liu, J. Liu, D. Chen, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 21049-21057. DOI:10.1002/anie.202007886 |

| [41] |

S. Liu, H. Ou, Y. Li, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 15146-15156. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c07193 |

| [42] |

Z. Zhang, X. Fang, Z. Liu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 3691-3698. DOI:10.1002/anie.201914397 |

| [43] |

Y. Zheng, Q. Li, J. Wu, et al., Chem. Sci. 12 (2021) 1843-1850. DOI:10.1039/d0sc04727a |

| [44] |

H. Zhou, X. Zeng, A. Li, et al., Nat. Commun. 11 (2020) 6183. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-19945-w |

| [45] |

J. Lin, X. Zeng, Y. Xiao, et al., Chem. Sci. 10 (2019) 1219-1226. DOI:10.1039/c8sc04363a |

| [46] |

F. Ding, Y. Zhan, X. Lu, et al., Chem. Sci. 9 (2018) 4370-4380. DOI:10.1039/c8sc01153b |

| [47] |

C. Tang, C. Song, Z. Wei, et al., Sci. China Chem. 63 (2020) 946-956. DOI:10.1007/s11426-020-9723-9 |

| [48] |

F. Ding, Z. Chen, W.Y. Kim, et al., Chem. Sci. 10 (2019) 7023-7028. DOI:10.1039/c9sc02466b |

| [49] |

A.L. Antaris, H. Chen, K. Cheng, et al., Nat. Mater. 15 (2016) 235-242. DOI:10.1038/nmat4476 |

| [50] |

A.L. Antaris, H. Chen, S. Diao, et al., Nat. Commun. 8 (2017) 15269. DOI:10.1038/ncomms15269 |

| [51] |

V. Singh, T. Guo, H. Xu, et al., Chem. Commun. 53 (2017) 9246-9249. DOI:10.1039/C7CC03471G |

| [52] |

R.A. Smaldone, R.S. Forgan, H. Furukawa, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 122 (2010) 8812-8816. DOI:10.1002/ange.201002343 |

| [53] |

L. Zhang, C. Yao, M. Gao, H. Li, World J. Gastroenterol. 11 (2005) 2830-2833. |

| [54] |

K. Kanatani, M. Ebata, M. Murakami, S. Okabe, J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 55 (2004) 207-222. |

| [55] |

W.L. Smith, R.M. Garavito, D.L. DeWitt, J. Biol. Chem. 271 (1996) 33157-33160. DOI:10.1074/jbc.271.52.33157 |

| [56] |

C.J. Hawkey, J. Naesdal, I. Wilson, et al., Gut 51 (2002) 336-343. DOI:10.1136/gut.51.3.336 |

| [57] |

B.L. Slomiany, J. Piotrowski, A. Slomiany, J. Endotoxin Res. 7 (2001) 203-209. DOI:10.1177/09680519010070030201 |

| [58] |

C.J. Hawkey, Gastroenterology 119 (2000) 521-535. DOI:10.1053/gast.2000.9561 |

| [59] |

Z. Li, X. Qiao, G. He, et al., Nano Res. 13 (2020) 3377-3386. DOI:10.1007/s12274-020-3025-0 |

2021, Vol. 32

2021, Vol. 32