Since the seminal work by Shaw and van Koten in the late 1970s, pincer ligands have been viewed as versatile supporting ligands for transition metals [1]. Generally, the tridentate coordination mode of pincer ligands results in strong binding to the central metal atom which displays a unique balance of high stability vs. reactivity that make pincer ligands privileged platforms for the design of catalysts. During the past three decades, the application of pincer complexes in organic transformations has made considerable progress [2]. The concept of the pincer is now very broad and a variety of compounds that feature pincer-type structure have been designed in recent years [3]. The pincer-type ligand has been widely used in coordination chemistry and such ligands enjoy many catalytic applications due to their activity and variety.

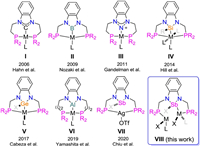

In contrast to the well established role of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus-based central donor atoms in pincer ligands, the chemistry of other donor atoms is less developed, and variations of the donor moieties have been explored to a limited extent. Research on N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-based (benz)imidazolium (PCP) type pincer complexes has been reported by Hahn and others (I, Fig. 1) [4-6], and the coordinating ability with Pd, Pt, Rh and Mo has been described. Such pincer complexes can work as effective catalysts for organic reactions and the formation of ammonia from dinitrogen under mild conditions. In 2009, Nozaki and co-workers reported a boron-based PBP pincer ligand (II, Fig. 1) and its coordination with an iridium(I) precursor via B-H oxidative addition [7]. Continuing this work, a series of groups 8–10 transition-metal complexes bearing this PBP ligand have been synthesized, further demonstrating their catalytic applications in transfer dehydrogenation of cyclooctane and oxidative addition of the C-C bond [8]. Peters et al. reported Co and Ni complexes based on the PBP pincer auxiliary ligand. These facilitate reversible H2 activation and could further serve as catalysts for olefin hydrogenation [9, 10]. Hill and other groups have described the synthesis of an N-heterocyclic silyl pincer ligand which undergoes chelate-assisted Si-H activation with transition metals to afford silyl pincer complexes (IV, Fig. 1) [11]. Stimulated by these development in pincer chemistry, analogues of carbene-based pincer ligands and the corresponding metal complexes have been reported by Cabeza and coworkers in recent years (V, Fig. 1) [12]. Besides the central donor based on groups 13 and 14 elements, Gandelman et al. in 2011, established nitrogen-derived NHC-analogues as ligands (III, Fig. 1) for transition metals chemistry. These analogs display weak σ-donor and reasonable π-acceptor abilities compared to NHCs [13]. In 2018, Thomas et al. reported a pincer ligand with a central N-heterocyclic phosphenium/phosphido donor, revealing the first example of H2 activation across a Co-P bond [14]. Very recently, Yamashita et al. reported the synthesis of a pincer-Ir(V) complex bearing an aluminyl ligand and its application to the transfer dehydrogenation of cyclooctane (VI, Fig. 1) [15].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Selected examples of PXP-type pincer complexes with phenylenediamine framework. | |

As a heavier analogue of phosphine, antimony has attracted much attention owing to the antimony-containing complexes which have found wide application in bond activation and catalytic transformations because of its high Lewis acidity [16]. The role of antimony as a central donor atom in pincer ligands has also been explored by Gabbai group [17]. While this PSbP-type pincer complex exhibits rich coordination and redox chemistry, the corresponding antimony-transition metal platforms have seen applications in anion sensing and catalytic transformation [18]. Encouraged by these advances, it is interesting to explore whether antimony could be introduced to the benzannulated ligand to synthesize a series of novel complexes. Herein, we report the synthesis of an antimony complex 1 and its reactivity towards to a series of inorganic salts and its coordination ability with metal precursors. Complex 1 can be viewed as a neutral PSbP ligand. It is worth mentioning that during the preparation of this manuscript, a series of species with cation PSb+P ligand were reported by Chiu et al. (VII, Fig. 1) [19].

Our ongoing interest in anionic nitrogen-phosphorus ligand [20] as well as metal-metal bond [21] stimulated us to design new PXP-type ligand and investigate its reactivity. Complex 1 was easily prepared by the reaction of SbCl3 with a phenylenediamine ligand in the presence of 2 equiv. of Et3N in THF (Scheme 1). The reaction immediately formed a bright-yellow suspension and was then stirred at room temperature for 2h. Complex 1 was isolated as a yellow solid in 95% yield and its structure was characterized by X-ray diffraction analysis, NMR spectroscopy, elemental analyses and high-resolution mass spectrometry. Its 31P{1H} NMR spectrum showed a single signal at -9.74 ppm from 2 equiv. phosphorus atoms (see Supporting information for details).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. The synthesis of complex 1. | |

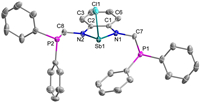

The single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of complex 1 revealed that it is a monomer in the solid state (Fig. 2) and that the antimony atom adopts a trigonal pyramidal configuration. The Sb1-Cl1 bond length is 2.5058(14) Å, which is shorter than that in a similar structure (2.646(2) Å) reported previously by Gudat [22]. The Sb1-N1 (2.024(3) Å) and Sb1-N2 (2.025(3) Å) bond lengths are very close, and are comparable with the corresponding bonds in the [(CH)2(NtBu)2SbCl] cyclic structure. The torsion angle of N2-C2-C1-C6 is 179.3°, suggesting that the antimony-contained heterocycle and the phenyl rings are almost co-planner. The distance of the Sb1-P1 (4.288Å) is much longer than that of the Sb1-P2 (3.258Å), and both of the Sb-P distances are longer than the sum of covalent radii for Sb and P (2.51Å) [23]. Apparently, the short length of the CH2PPh2 sidearm prevents intramolecular donor-acceptor interactions between the P atoms and the Sb atom. One of the sidearm phenyl rings in complex 1 displays a weak interaction with the antimony thus causing the phosphorus atom to be located in an axial direction, which could explain the reason for the longer Sb1-P1 distance.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Molecular structure of complex 1 (drawn with 50% probability). All the hydrogen atoms were omitted for clarity. | |

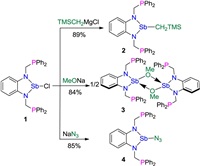

With complex 1 in hand, we first examined its reactivity with TMSCH2Li in toluene at room temperature (Scheme 2) and found that the colour of the system immediately changed from yellow to red-orange. The alkylation reaction, however, gave a complex mixture of intractable products according to the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum. When TMSCH2MgBr was used in this reaction instead of TMSCH2Li, only a single signal at -12.65 ppm was observed in 31P{1H} NMR spectrum and led to the isolation of a complex 2 as a red-orange solid in 89% yield. The 1H NMR spectrum revealed that the methylene groups connecting the N and P atoms exhibit doublets at 4.28 and 3.67 ppm while the methylene connected to the antimony gave a signal at 0.05 ppm.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. The reactivity of complex 1. | |

The solid-state structure of 2 was confirmed by single crystal X-ray diffraction (Fig. 3). The major structural features of 2 are similar to those of 1. The bond length of Sb1-C33 is 2.170(5) Å and it was revealed that the Sb-π interaction through the phenyl rings in the PPh2 unit had disappeared in the alkyl-antimony complex, which is consistent with the short Sb1-P1 distance (3.385Å). Transition metals and actinide hydrides have been thought to be intermediates in catalytic transformation, and an effective method to yield these species is combination of the alkyl complex with hydrides [24]. Use complex 2 with HBPin or PhSiH3 as the hydride source to synthesize Sb-H species failed, no reaction being detected even with heating and the reaction of 1 with LiBEt3H or NaBEt3H gave complicated decomposition product. These experimental results demonstrated that an appropriate ligand could be an important feature contributing to the stability of the active antimony hydride. Very recently, Chitnis et al. reported the first example of naphthalenediamine based antimony hydride and its hydrostibination reaction with unsaturated bonds [25].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Molecular structure of complex 2 (drawn with 50% probability). All the hydrogen atoms were omitted for clarity. | |

Having established the reactions of substituted versions of 1, we further explored the alkoxide and azide derivatives of PSbP complex. Treatment of a solution of 1 in THF with MeONa or NaN3 results in a pale-yellow mixture, from which complex 3 was isolated in 84% yield and 4 in 85% yield, respectively. The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of 3 shows a single signal at -13.41 ppm and that of 4 has only a signal at -7.07 ppm, indicating equivalence of the phosphorus atoms in both 3 and 4 in solution.

The solid-state structures of 3 and 4 were determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction (Fig. 4). It was found that 3 is a dimer in the solid state. The unit cell contains two molecules with similar structural features connected by intermolecular Sb-O interaction. The bond length of Sb1-O1 is 2.041(3) Å in the planar five-membered heterocycle, which is shorter than the Sb1-O1' distance (2.469(2) Å). However, 4 displayed a monomer structure. The bond length of Sb1-N3 (2.180(6) Å) was slightly longer than Sb1-N1 (2.022(4) Å) and N2-Sb1 (2.030(4) Å), which may be attributed to the tendency to planarity of the antimony atom. It was observed that the structures of 3 and 4 showed one of the sidearm phosphorus atoms located in the axial direction, which differs from the alkyl complex 2.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Molecular structures of complexes 3 and 4 drawn with 50% probability (all the hydrogen atoms and phenyl rings in the sidearm were omitted for clarity). | |

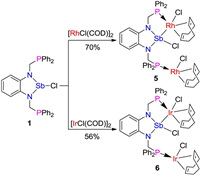

In order to further explore the coordination properties of the PSbP complex, we examined the reactions of 1 with Ir(I) or Rh(I) precursors in toluene at room temperature. As shown in Scheme 3, the reaction mixture immediately forms a dark brown solution for complex 5 and green system for complex 6, which were isolated in 70% and 56% yield, respectively. In the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum, the two phosphorus atoms in 5 exhibited a doublet signal at 31.68 ppm (JRh-P =150.4Hz). The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of 6 showed a singlet at 17.43 ppm. Attempts to synthesize mononuclear metal complex through the stoichiometry reaction failed and it was suggested that the coordination reaction selectively forms a binuclear complex.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 3. The coordination reactivity of 1. | |

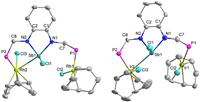

Analysis of the X-ray crystal structure of 5 and 6 demonstrated that the structural features are very similar. As shown in Fig. 5, both 5 and 6 form an asymmetric structure in the crystalline state. One of the transition metal centers in 5 and 6 are pentadentate coordinated and the geometry of the antimony center is a distorted square pyramid. The other Rh atom is coordinated with phosphine, and the bond distance of Sb1-Rh1 (4.173Å) was much longer than Sb1-Rh2 (2.9433(4) Å), which suggests that there is no interaction between Sb1 and Rh1. The bond distance of Rh1-P1 (2.3107(10) Å) is slightly longer than Rh2-P2 (2.2836(10) Å, and this may be attributed to the weak Rh-Sb donor interaction. The bond distance of Sb1-Ir2 is 2.9965(12) Å in 6, and is comparable with the bond distance of Sb1-Rh2. However, both of the Sb-Rh and Sb-Ir distances are longer than that in the Sb+-transition metal (TM) interaction. Attempted to obtain a heterobimetallic species containing Sb-TM covalent bonds by the reduction of 5 and 6 were unsuccessful [26].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. X-ray molecular structures of complexes 5 and 6 drawn with 50% probability (all the hydrogen atoms and phenyl rings in the sidearm were omitted for clarity). | |

In conclusion, we have prepared an antimony complex 1 based on dianionic nitrogen-phosphorus ligand. This complex exhibits good reactivity with a series of inorganic salts, yielding monomer or dimer products. The neutral PSbP complex can coordinate with Ir(I) and Rh(I), giving the corresponding dinuclear complex. Complex 1 clearly expands the family of PXP type ligand. The coordination reactivity with other transition metals is currently under investigation.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare no competing financial interests.

AcknowledgmentsThis research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21772088 and 91961116), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 14380216), the Young Elite Scientist Sponsorship Program of China Association of Science and Technology, the Program of Jiangsu Specially-Appointed Professor, and Shuangchuang Talent Plan of Jiangsu Province.

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2020.07.006.

| [1] |

(a) C.J. Moulton, B.L. Shaw, J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. (1976) 1020-1024; (b) G. Van Koten, K. Timmer, J.G. Noltes, A.L. Spek, J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. (1978) 250-252. |

| [2] |

(a) J. Choi, A.H.R. MacArthur, M. Brookhart, A.S. Goldman, Chem. Rev. 111 (2011) 1761-1779; (b) E. Peris, R.H. Crabtree, Chem. Soc. Rev. 47 (2018) 1959-1968; (c) H.A. Younus, N. Ahmad, W. Su, F. Verpoort, Coord. Chem. Rev. 276 (2014) 112-152. |

| [3] |

(a) D. Morales-Morales, C.M. Jensen, The Chemistry of Pincer Compounds, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2007; (b) G. van Koten, D. Milstein, Organometallic Pincer Chemistry, SpringerVerlag, Berlin-Heidelberg, 2013; (c) G.R. Freeman, J.A.G. Williams, Metal complexes of pincer ligands: excited states, photochemistry, and luminescence, in: G. van Koten, D. Milstein (Eds. ), Organometallic Pincer Chemistry, Springer, Berlin, 2013, pp. 89-129; (d) C. Gunanathan, D. Milstein, Chem. Rev. 114 (2014) 12024-12087; (e) H. Valdes, L. Gonzalez-Sebastian, D. Morales-Morales, J. Organomet, Chem. 845 (2017) 229-257. |

| [4] |

(a) H.M. Lee, J.Y. Zeng, C.H. Hu, M.T. Lee, Inorg. Chem. 43 (2004) 6822-6829; (b) T. Steinke, B.K. Shaw, H. Jong, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 (2009) 10461-10466; (c) B.K. Shaw, B.O. Patrick, M.D. Fryzuk, Organometallics 31 (2012) 783-786. |

| [5] |

A. Plikhta, A. Pothig, E. Herdtweck, B. Rieger, Inorg. Chem. 54 (2015) 9517-9528. |

| [6] |

A. Eizawa, K. Arashiba, H. Tanaka, et al., Nat. Commun. 8 (2017) 1-12. |

| [7] |

Y. Segawa, M. Yamashita, K. Nozaki, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 (2009) 9201-9203. |

| [8] |

(a) M. Hasegawa, Y. Segawa, M. Yamashita, K. Nozaki, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51 (2012) 6956-6960; (b) M. Yamashita, Bull. Chem. Soc. Japan. 89 (2016) 269-281; (c) E.H. Kwan, H. Ogawa, M. Yamashita, ChemCatChem 9 (2017) 2457-2462. |

| [9] |

T.P. Lin, J.C. Peters, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 15310-15313. |

| [10] |

T.P. Lin, J.C. Peters, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 13672-13683. DOI:10.1021/ja504667f |

| [11] |

(a) L.S. Dixon, A.F. Hill, A. Sinha, J.S. Ward, Organometallics 33 (2014) 653-658; (b) Z. Xiong, X. Li, S. Zhang, Y. Shi, H. Sun, Organometallics 35 (2016) 357-363; (c) B.J. Frogley, A.F. Hill, M. Sharma, A. Sinha, J.S. Ward, Chem. Commun. 56 (2020) 3532-3535. |

| [12] |

(a) L. Álvarez-Rodríguez, J. Brugos, J.A. Cabeza, et al., Chem. Commun. 53 (2017) 893-896; (b) J. Brugos, J.A. Cabeza, P. Garcia-Alvarez, E. Pe'rez-Carreño, Organometallics 37 (2018) 1507-1514; (c) J. Brugos, J.A. Cabeza, P. García-Álvarez, E. Pérez-Carreño, D. Polo, Dalton Trans. 47 (2018) 4534-4544. |

| [13] |

(a) Y. Tulchinsky, M.A. Iron, M. Botoshansky, M. Gandelman, Nat. Chem. 3 (2011) 525-531; (b) Y. Tulchinsky, S. Kozuch, P. Saha, et al., Chem. Sci. 5 (2014) 1305-1311. |

| [14] |

(a) G.S. Day, B. Pan, D.L. Kellenberger, B.M. Foxman, C.M. Thomas, Chem. Commun. 47 (2011) 3634-3636; (b) A.M. Poitras, S.E. Knight, M.W. Bezpalko, B.M. Foxman, C.M. Thomas, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 1497-1500. |

| [15] |

S. Morisako, S. Watanabe, S. Ikemoto, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 15031-15035. |

| [16] |

(a) S. Kobayashi, T. Busujima, S. Nagayama, Chem. Eur. J. 6 (2000) 3491-3494; (b) S. Thibaudeau, A. Martin-Mingot, M.P. Jouannetaud, O. Karam, F. Zunino, Chem. Commun. (2007) 3198-3200; (c) A. Saito, M. Umakoshi, N. Yagyu, Y. Hanzawa, Org. Lett. 10 (2008) 1783-1785; (d) A. Saito, J. Kasai, Y. Odaira, H. Fukaya, Y. Hanzawa, J. Org. Chem. 74 (2009) 5644-5647; (e) F. Liu, A. Martin-Mingot, M.P. Jouannetaud, F. Zunino, S. Thibaudeau, Org. Lett. 12 (2010) 868-871. |

| [17] |

(a) J.S. Jones, F.P. Gabbai, Acc. Chem. Res. 49 (2016) 857-867; (b) D. You, F.P. Gabbaï, Trends in Chemistry 1 (2019) 485-496. |

| [18] |

(a) C.R. Wade, F.P. Gabbaï, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50 (2011) 7369-7372; (b) C.R. Wade, I.S. Ke, F.P. Gabbaï, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51 (2012) 478-481; (c) I.S. Ke, F.P. Gabbaï, Inorg. Chem. 52 (2013) 7145-7151; (d) I.S. Ke, J.S. Jones, F.P. Gabbaï, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53 (2014) 2633-2637; (e) J.S. Jones, C.R. Wade, F.P. Gabbaï, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53 (2014) 8876-8879; (f) H. Yang, F.P. Gabbaï, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137 (2015) 13425-13432; (g) J.S. Jones, C.R. Wade, F.P. Gabbaï, Organometallics 34 (2015) 2647-2654; (h) J.S. Jones, F.P. Gabbai, Chem. Eur. J. 23 (2017) 1136-1144; (i) D. You, F.P. Gabbaï, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 6843-6846. |

| [19] |

N.K. Srungavruksham, Y.H. Liu, M.K. Tsai, C.W. Chiu, Inorg. Chem. 59 (2020) 4468-4474. |

| [20] |

(a) X. Sun, Q. Zhu, Z. Xie, et al., Chem. Eur. J. 25 (2019) 14295-14299; (b) X. Sun, W. Su, K. Shi, Z. Xie, C. Zhu, Chem. Eur. J. 26 (2020) 5354-5359. |

| [21] |

(a) G. Feng, M. Zhang, D. Shao, et al., Nat. Chem. 11 (2019) 248-253; (b) G. Feng, M. Zhang, P. Wang, et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116 (2019) 17654-17658; (c) X. Xin, C. Zhu, Dalton Trans. 49 (2020) 603-607; (d) G. Feng, K.N. McCabe, S. Wang, L. Maron, C. Zhu, Chem. Sci. (2020), doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/D0SC00389A. |

| [22] |

D. Gudat, T. Gans-Eichler, M. Nieger, Chem. Commun. (2004) 2434-2435. |

| [23] |

P. Pyykkö, M. Atsumi, Chem. Eur. J. 15 (2009) 186-197. |

| [24] |

(a) D. Gudat, A. Haghverdi, M. Nieger, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39 (2000) 3084-3086; (b) S. Harder, J. Brettar, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45 (2006) 3474-3478; (c) J. Spielmann, D. Piesik, B. Wittkamp, G. Jansen, S. Harder, Chem. Commun. (2009) 3455-3456; (d) M. Arrowsmith, T.J. Hadlington, M.S. Hill, G. Kociok-Köhn, Chem. Commun. 48 (2012) 4567-4569; (e) S. Schnitzler, T.P. Spaniol, L. Maron, J. Okuda, Chem. Eur. J. 21 (2015) 11330-11334; (f) C.C. Chong, H. Hirao, R. Kinjo, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53 (2014) 3342-3346; (g) C.C. Chong, H. Hirao, R. Kinjo, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 190-194; (h) C.C. Chong, R. Kinjo, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 12116-12120; (i) Z. Yang, M. Zhong, X. Ma, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 10225-10229; (j) J.K. Pagano, J.M. Dorhout, R. Waterman, K.R. Czerwinski, J.L. Kiplinger, Chem. Commun. 51 (2015) 17379-17381; (k) S. Bagherzadeh, N.P. Mankad, Chem. Commun. 52 (2016) 3844-3846. |

| [25] |

K.M. Marczenko, J.A. Zurakowski, K.L. Bamford, J.W. MacMillan, S.S. Chitnis, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 18096-18101. |

| [26] |

N. Hara, T. Saito, K. Semba, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 7070-7073. |

2021, Vol. 32

2021, Vol. 32