b School and Hospital of Stomatology, China Medical University, Shenyang 110002, China;

c State Key Laboratory of Heavy Oil Processing, College of Science, China University of Petroleum, Beijing 102249, China;

d School and Hospital of Stomatology, Jilin University, Changchun 130021, China;

e Department of Neurosurgical Oncology, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130021, China

Human bone mesenchymal stem cells (hBMSCs) are intensively used in many chemistry biology and clinic fields due to unique pluripotency [1-5]. Especially in musculoskeletal diseases and tooth injuries, the participation of hBMSCs is particularly important since the limited regenerative ability of bone in damaged sites. Therefore, the materials which can accelerate the osteoblast-oriented differentiation attract increasing attention [6, 7]. Traditional strategies include commercial osteogenic induction medium and some soluble factors such as growth factors, cytokines and so on. Most of cues are expensive and some of them are from animals which possesses potential danger [8]. Therefore, a great many of studies rely on commercial osteogenic induction medium. However, the short storage time and limited effect restrict the application of osteogenic induction medium in clinic. Hence, it is urgent to develop a novel reagent with better effect in accelerating osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs for clinical application.

Gold nanodots (Au NDs) attract increasing attention on account of adjustable sizes and morphologies, stable chemical structures and properties, easy-modified surfaces as well as low toxicity [9-11]. Some works have been done to study the role of Au NDs in the differentiation of stem cells, and it is revealed that physicochemical properties are of great significance [3, 4]. However, the influence of Au NDs with highly negative charges in osteogenic differentiation is not clarified deeply and detailly. And for further study, the osteogenesis is influenced by various ways, and the wide explorations are beneficial to reveal this process. In this work, the linkage between osteogenesis and autophagy are exhibited, which is triggered via Au NDs with highly negative charges.

As superficial charges provider, the selection of ligand on Au NDs is very important. Oligopeptides are preferred due to the good biocompatibility compared to alkanethiol with high toxicity. In view of the strong bound between sulfydryl and gold, both cysteine (Cys) and glutathione (GSH) with sulfydryl are good candidates. Cys is linear structure, which possesses smaller steric hindrance compared to GSH with dendritic structure. Different structures of the oligopeptides endow different amount of superficial negative charges on Au NDs, which can be used to figure out the charge influence in osteogenic differentiation.

Addressing the challenges above, the Au NDs with spherical morphology and ultra-small size capped by Cys and GSH were designed (Schemes S1 and S2 in Supporting information). Two kinds of fluorescent Au NDs with different amount of negative charges possessed similar sizes (~2 nm), hBMSCs uptake doses, as well as same exterior functional groups for studying the surface charges precisely. Different from general reported works, the hBMSCs were co-culturing with Au NDs in general medium (GM). While the hBMSCs cultured in commercial osteogenic induction medium were set as control group. Owing to the ultra-small size, Au NDs emitted bright and stable fluorescence which can be used for real-time tracing during the whole process. And the differentiation dynamics were analyzed in multi-aspects covering ALP activity, relative gene expressions, and cytoskeleton formation (Scheme 1). Furthermore, several signaling pathways were monitored to figure out the factors of osteogenesis differentiation. And to prove the universality of the data deeply, Ag NDs and CDs with similar size (~2 nm), same exterior functional groups and different amount surface negative charges were synthesized and analyzed.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. The synthetic route of bright fluorescent Au-Cys NDs and Au-GSH NDs, as well as the further application for inducing osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs. | |

Through the observation of TEM, both the prepared Au NDs were spherical with similar diameter (Figs. 1a and b). According to the statistical size distribution, the Au-Cys (~1.9 nm, Fig. 1c) was closed to Au-GSH (~2.4 nm, Fig. 1d). And the crystal lattices of two Au NDs were 2.35 Å monitored by HRTEM shown in Figs. 1a and b insets. The results fitted well with Au (111) lattice spacing of face-centered cubic [12]. Au-Cys and Au-GSH gave off strong fluorescence with maximal excitation and emission wavelength at 405/490 nm and 410/609 nm respectively (Figs. 1e and f). The aqueous solutions were yellow transparent liquid with blue emission (Fig. 1e inset) and light-yellow transparent liquid with red emission (Fig. 1f inset). Quantum yield (Q) of Au-Cys in aqueous solution was about 8.4% and Au-GSH in aqueous solution was about 5.1%, using quinine sulfate (0.1 mol/L H2SO4 as solvent, Q = 55%) as reference. On account of the procedure of hBMSCs differentiate into osteoblasts needed a little longer time, and fluorescence stability was continuously tested during three months. As shown in Figs. S1a and b (Supporting information), the fluorescence intensities of Au-Cys and Au-GSH were steady without shift of peak position, which guaranteed fluorescence visualization over whole hBMSCs differentiation course and bone repair process. UV–vis absorption spectra were displayed in Fig. S2 (Supporting information). Distinguished from large Au nanoparticles (over 10 nm), there was no peak around 500 nm. Consisting with previous works [13], it indicated the formation of nanodots below 10 nm with the coincidence of TEM (Figs. 1a and b).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. TEM images of Au-Cys (a) and Au-GSH (b). Insets of (a) and (b): HRTEM images indicated the crystal lattices were 0.235 nm. Size distribution of Au-Cys (c) was about 1.9 nm and Au-GSH (d) was about 2.4 nm. (e) and (f) were fluorescent spectra of Au-Cys and Au-GSH with excitation and emission peaks of 405/490 nm and 410/609 nm, respectively. Inset photographs were Au NDs aqueous solution under visible light and UV light (365 nm). Zeta potential of Au-Cys (g) and Au-GSH (h) were negative charged of ca. -51 mV and ca. -19 mV, owing to the existence of -COO- in cysteine and glutathione. | |

The composition and valence states of Au-Cys and Au-GSH were similar, which depicted by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) in Fig. S3 (Supporting information). The binding energy peaks of Au 4f situated at 88.2 eV and 84.3 eV, which were corresponded to Au(0) and Au(I). Au(0) took shape of the nanodots core, because it was easy to assemble [14]. And the presence of Au(I) contributed a lot to the stabilization of nanodots due to the strong Au-S bond (-112.45 kcal/mol), and stopped them from growing bigger. The Au-S bond tightly bonded the ligands (Cys and GSH) to Au nanodots and ensured the energy interaction between ligands and Au to emit bright fluorescence [15, 16]. Due to the existence of -COO- on Cys and GSH, Au-Cys and Au-GSH were both negative charges. The charges repelled each other, resulting in the stability of nanodots aqueous solution over even 3 months. However, Au-Cys possessed more charges (ca. -51 mV, Fig. 1g) than Au-GSH (ca. -19 mV, Fig. 1h), which was attributed to the structures of Cys and GSH. The –SH of GSH located at the middle of molecule, and the residual parts had large space steric resistance just like arborization when Au-S bond was formed. It resulted that less GSH can bind to Au. On the contrary, the –SH of Cys sited on the end of molecule, the remained portion possessed small space steric resistance like grass when Au-S bond was formed. It led to more Cys binding to Au. Also, the results were proved via XPS. XPS showed that the percentage of S was 4.94% in Au-Cys and 2.26% in Au-GSH. The S proportion can verify the ratio of ligand, because Cys and GSH both have only one –SH group in molecule. Therefore, Au-Cys and Au-GSH only showed difference on surface charges which can explore the charge influence in osteogenic induction of hBMSCs more accurately.

For further test in vitro and in vivo, the biological toxicity of materials is pretty important. Hence, the toxicities of Au-Cys and Au-GSH with gradient concentrations were monitored firstly by MTT assay. As shown in Fig. S4 (Supporting information), Au-Cys and Au-GSH were quite low toxic to hBMSCs at concentration 0, 50, 100, 200, 300, 500 mg/L for three days. Au-GSH even promoted hBMSCs proliferation a little at concentrations 50 and 100 mg/L (Fig. S4b). The Au-Cys and Au-GSH had good biocompatibility with great potential for biological applications. On account of this consequence, following experiments all used 50 mg/L dose. The favorable outcome was predictable because Cys and GSH are common oligopeptides in organisms.

Based on the bright fluorescence of Au-Cys and Au-GSH, the interaction between Au NDs and hBMSCs were traced. After culturing the hBMSCs with Au NDs for 1 day, 7 days, 14 days, and 21 days, the cells intake were observed by laser scanning confocal microscope (Fig. S5 in Supporting information) and the results were qualitative and quantitative analyzed via the bright blue emission of Au-Cys and the bright red emission of Au-GSH. It displayed an obvious cellular uptake of Au-Cys after culturing 1 day. And Au-Cys were mainly located at cytoplasm monitored from fluorescence images from Fig. S5a. Even though the nuclear pore of hBMSCs is greater than 10 nm, the condense structure of nucleus made it hard to enter in. Meanwhile, Au-Cys can be held in hBMSCs through a relatively long time (21 days) with a little increased uptake quantitated in Fig. S5c. And the cellular morphology kept well at 21st day showed in the bright field, which implied good biocompatibility of Au-Cys. Similar phenomenon was also discovered from Au-GSH in uptake efficiency and tendency (Figs. S5b and d). The similar uptake amount of Au-Cys and Au-GSH made it clearer to explore the charge influence for osteogenic differentiation.

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity is a crucial marker for osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs [17]. After culturing in general induction medium (GM, Fig. S6a in Supporting information), osteogenic induction medium (OM, Fig. S6b in Supporting information) and with Au-Cys (Fig. S6c in Supporting information, in GM), Cys (Fig. S6d in Supporting information, in GM), hBMSCs were stained to measure ALP activity. The staining intensity and proportion showed the osteogenic differentiation rate of hBMSCs. Comparing the pictures in Fig. S6 (Supporting information), it was revealed visually that the ALP activity of hBMSCs treated with Au-Cys indicated best effect. Quantified result was shown in Fig. 2a, the ALP activity of hBMSCs treated with Au-Cys displayed 3.8 folds than control group, and 2.5 folds than commercial osteogenic induction medium (OM group). Meanwhile, the result indicated least degree when hBMSCs treated with Cys. It demonstrated Au-Cys can increase activity of ALP in osteogenic differentiation process, and the promotion did not totally rely on its ligand, the nano structure also took an essential effect. To explore the influence of surface charges on the Au NDs, the contrast data of Au-Cys (ca. -51 mV) and Au-GSH (ca. -19 mV) were revealed in Fig. S7 (Supporting information). It was depicted that the ALP staining of hBMSCs culturing with Au-Cys showed significant denser than Au-GSH. Quantified result (Fig. S7c) verified that the ALP activity of hBMSCs culturing with Au-Cys displayed 1.6 folds than Au-GSH. It can be inferred from the results that the more negative charges on the Au NDs surface, the more obvious promotion of osteogenic differentiation occurred.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) The diagram of quantitative ALP activity assay of hBMSCs culturing in general induction medium (control), osteogenic induction medium (OM) and with Au-Cys and Cys. (b) Real time RT-PCR analysis of ALP gene expression in hBMSCs upon treatment with Au-Cys for 3 days, 5 days, 7 days, and 14 days. Real time RT-PCR analysis of characteristic gene expressions concluding BMP2, SP7, and RUNX2 in hBMSCs with incubation Au-Cys, Cys (c) and Au-GSH, GSH (d) for 7 days. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. | |

In order to confirm the osteogenic differentiation consequence of Au NDs from multiple aspects, several characteristic gene expressions related to osteogenesis were analyzed, such as ALP gene, β-actin (ACTb) gene, Bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP2) gene, Specificity phosphatase-7 (SP7), Runt-related gene-2 (RUNX2) [18-20]. The relative genes were all took into consideration, expressing from early to later and regulating the course from mineralization to mature osteoblasts. As shown in Fig. 2c, Au-Cys induced osteogenic gene expressions up-regulation such as BMP2, SP7, and RUNX2, especially SP7 and RUNX2 were 2 folds than control. And Cys as the ligands led to down-regulation or minimal up-regulation in gene expressions. It proved the importance of nanostructure which was beneficial to the adherency of cell. At the same time, Au-GSH did not exhibit as well as Au-Cys in BMP2, SP7, and RUNX2 gene expressions (Fig. 2d). The results revealed that Au-Cys with more surface negative charges displayed further promotion of characteristic gene expressions. And the acceleration of differentiation came from both the nanostructure and the surface charges. These results were in agreement with ALP activities.

To clarify the process of gene expressions, the expression of ALP gene was explored in details at 3 days, 5 days, 7 days, and 14 days (Fig. 2b). From 3 days to 7 days, the ALP expression increased gradually after culturing with Au-Cys. Particularly on the 7th day, the ALP expression stimulated by Au-Cys was nearly 3 folds than control. Then, ALP gene transcribed and translated into protein soon after, accompanying with the declination of ALP gene on the 14th day (Fig. 2b). And the results accorded well with ALP staining. Alkaline phosphatase, translated from ALP gene, was stained in large area with strong intensity after treatment via Au-Cys. It demonstrated that Au-Cys possessed excellent capacity in promoting osteogenic differentiation from hBMSCs at gene and protein level.

To further investigate the osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs, experiments at cell level were studied. Cytoskeleton is the main support of cells. Strong mechanical property coming from cytoskeleton makes great contribution to osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs. The brighter fluorescence from staining indicated the more formation of cytoskeleton, which inspected the differentiation of hBMSCs after culturing with Au-Cys and Au-GSH (Figs. S8 and S9 in Supporting information). It can be seen from the pictures that cytoskeleton staining of hBMSCs with incubation Au-Cys exhibited brighter and stronger fluorescence compared to Au-GSH (Fig. S9) and osteogenic induction medium (Fig. S8). As shown in Fig. S9c and Fig. S8e diagram, it was quantitative. The results implied that Au-Cys displayed better effect in promoting the formation of cytoskeleton.

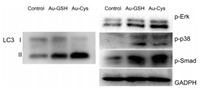

For exploring the mechanism of differentiation, western blotting measurements were designed. Several mainly related signal pathways were monitored, such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) as well as autophagy signaling. Many researches have been verified the importance of autophagy in process of osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs. In the early stage of osteogenic differentiation, the level of autophagy in hBMSCs will increase significantly [21]. Meanwhile, autophagy can improve mineralization capacity, promote osteogenic differentiation and facilitate bone formation [22, 23]. MAPK mediates the transformation of mechanical signals into biochemical signals. TGF-β plays an important role in cells proliferation and differentiation. And the related results were illustrated in Fig. 3. Data proved that Au-Cys promoted osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs through autophagy signaling by enhancing LC3, which including LC3 Ⅰ and LC3 Ⅱ. When autophagosomes are formed, cytosolic LC3 (LC3 Ⅰ) will enzymatically remove a small segment of peptide and change to membrane-type LC3 (LC3 Ⅱ). An increase in LC3 Ⅱ represents autophagy start up [24]. The ratio of LC3 Ⅱ to LC3 Ⅰ represents the degree of autophagy. And MAPK (p-Erk, p-p38) and TGF-β (p-Smad), did not show obvious difference between Au-Cys and Au-GSH. The nanomaterial can get into cells via vesicle through endocysis, and the vesicle enclosed nanomaterials will form lysosome in the end [25]. Meanwhile, the autophagy process started from lysosome, because the highly acidic organelle can degrade protein, carbohydrate and so on. Therefore, it can be inferred that the Au-Cys with highly negative charges triggered osteogenic differentiation via autophagy starting from lysosome.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Western blotting patterns of autophagy signal (LC 3), MAPK (p-Erk, p-p38) and TGF-β (p-Smad) after incubating for 24 h with Au-GSH and Au-Cys. Results were normalized to the internal control GAPDH. | |

For exploring the universality of the conclusion, Ag nanodots (Ag NDs) as well as carbon nanodots (CDs) with different amount surface negative charges were designed (Scheme S3 in Supporting information). The prepared nanodots were all spherical in shape and uniform in size, with diameter of ~2.1 nm (Ag-Cys), ~2.5 nm (Ag-GSH) ~1.8 nm (Cys-CDs), and ~2.2 nm (GSH-CDs), respectively (Fig. S10 in Supporting information). But the zeta potential showing the surficial negative charges differed greatly from each other, Ag-Cys and Cys-CDs possessed more negative charges of ca. -52.5 mV and ca. -38.9 mV, while Ag-GSH and GSH-CDs exhibited fewer negative charges of ca. -17.9 mV and ca. -15.1 mV (Fig. S11 in Supporting information). Cytoskeleton staining of hBMSCs was monitored after culturing with Ag NDs and CDs. As shown in Figs. S12c and f (Supporting information) diagrams, the quantitative results exhibited Ag-Cys and Cys-CDs performed better than Ag-GSH and GSH-CDs. And it can be seen visually in the corresponding fluorescence images (Figs. S12a, b, d and e in Supporting information). The results deduced that plenty surface negative charges were vital to promote osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs.

In this work, fluorescent Au-Cys with large number of negative charges on surface were prepared as osteoinductive agent of hBMSCs. It even had better consequence on ALP activity and cytoskeleton formation than commercial osteogenic induction medium. To explore charge effect, Au-GSH with fewer negative charges was synthesized. And it did not behave as well as Au-Cys in ALP activity, relatively gene expressions, and cytoskeleton staining. Furthermore, Ag NDs as well as CDs were prepared to explore the charge influence deeply. The results all implied that more negative charges possessed better behavior in osteogenic induction. And the reason of osteogenic differentiation may root in autophagy of hBMSCs.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors report no declarations of interest.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51861145311, 22005338), Science Foundation of China University of Petroleum, Beijing (No. 2462017YJRC027). We thank professor Hongdong Li for the guidance and suggestions in this work and Open Project of State Key Laboratory of Superhard Materials (Jilin University 201802).

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2020.10.031.

| [1] |

Q. Wang, J.X. Xu, H.M. Jin, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 28 (2017) 1801-1807. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2017.07.011 |

| [2] |

C.K.K. Choi, J.M. Li, K.C. Wei, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137 (2015) 7337-7346. DOI:10.1021/jacs.5b01457 |

| [3] |

J.C. Li, X.M. Li, J. Zhang, N. Kawazoe, G.P. Chen, Adv. Healthc. Mater. 6 (2017) 1700317. DOI:10.1002/adhm.201700317 |

| [4] |

J.C. Li, J.E.J. Li, J. Zhang, et al., Nanoscale 8 (2016) 7992-8007. DOI:10.1039/C5NR08808A |

| [5] |

L. Zhong, D.R. Hu, Y. Cu, et al., J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 15 (2019) 857-877. DOI:10.1166/jbn.2019.2761 |

| [6] |

Y. Xiao, J.R. Peng, Q.Y. Liu, et al., Theranostics 10 (2020) 1500-1513. DOI:10.7150/thno.39471 |

| [7] |

X. Chen, X. Liu, K. Huang, Chin. Chem. Lett. 30 (2019) 797-800. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2018.11.011 |

| [8] |

A. Bachhuka, B. Delalat, S.R. Ghaaemi, et al., Nanoscale 9 (2017) 14248-14258. DOI:10.1039/C7NR03131A |

| [9] |

J.C. Li, Y. Chen, N. Kawazoe, G.P. Chen, Nano Res. 11 (2018) 1247-1261. DOI:10.1007/s12274-017-1738-5 |

| [10] |

A.K. Parchur, G. Sharma, J.M. Jagtap, et al., ACS Nano 12 (2018) 6597-6611. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.8b01424 |

| [11] |

H.L. Zhang, P.F. Xu, X.T. Zhang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 1083-1086. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2019.10.005 |

| [12] |

Y.Q. Sun, D.D. Wang, Y.Q. Zhao, et al., Nano Res. 11 (2018) 2392-2404. DOI:10.1007/s12274-017-1860-4 |

| [13] |

Y.Q. Sun, J.P. Wu, C.X. Wang, Y.Q. Zhao, Q. Lin, New J. Chem. 41 (2017) 5412-5419. DOI:10.1039/C7NJ00175D |

| [14] |

Y. Chen, Y. Wang, C.X. Wang, et al., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 396 (2013) 63-68. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2013.01.031 |

| [15] |

Z.T. Luo, X. Yuan, Y. Yu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134 (2012) 16662-16670. DOI:10.1021/ja306199p |

| [16] |

G.B. Gao, R. Chen, M. He, et al., Biomaterials 194 (2019) 36-46. DOI:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.12.013 |

| [17] |

J.Q. Wei, Y. Liu, X.H. Zhang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 28 (2017) 845-850. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2017.01.008 |

| [18] |

D.D. Liu, C.Q. Yi, D.W. Zhang, J.C. Zhang, M.S. Yang, ACS Nano 4 (2010) 2185-2195. |

| [19] |

F.S. Wang, C.J. Wang, S.M. Sheen-Chen, et al., J. Biol. Chem. 277 (2002) 10931-10937. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M104587200 |

| [20] |

C.Q. Yi, D.D. Liu, C.C. Fong, J.C. Zhang, M.S. Yang, ACS Nano 4 (2010) 6439-6448. DOI:10.1021/nn101373r |

| [21] |

A. Nuschke, M. Rodrigues, D.B. Stolz, et al., Stem Cell Res. Ther. 5 (2014) 140-154. DOI:10.1186/scrt530 |

| [22] |

K.H. Chang, A. Sengupta, R.C. Nayak, et al., Cell Rep. 9 (2014) 2084-2097. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.031 |

| [23] |

M. Nollet, S. Santucci-Darmanin, V. Breuil, et al., Autophagy 10 (2014) 1965-1977. DOI:10.4161/auto.36182 |

| [24] |

M.B.E. Schaaf, T.G. Keulers, M.A. Vooijs, K.M.A. Rouschop, FASEB J. 30 (2016) 3961-3978. DOI:10.1096/fj.201600698R |

| [25] |

N. Zhou, S.J. Zhu, S. Maharjan, et al., RSC Adv. 4 (2014) 62086-66209. |

2021, Vol. 32

2021, Vol. 32