b Advanced Research Institute of Multidisciplinary Science, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing 100081, China;

c National Chromatographic Research and Analysis Center Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Science, Dalian 116011, China

Aptamers are short ssDNA or RNA sequences which are capable for target molecules recognizing, and can be typically selected from a random oligonucleotide library through a process termed systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) [1-3]. This process generally involves iterated rounds of interaction between library and target, and followed by partition of complex from the unbound oligonucleotide library, and alternated steps of PCR amplification for the generation of sub-libraries till to the final sequencing [4-7]. During repeat rounds, unbound and weakly bound oligonucleotides are continuously removed, and the strongly bound are retained on the targets as high-affinity candidates. To improve their specificity, negative or counter selection is also required [8-10]. So, aptamers are expected to be finally obtained with significant consumption.

To accelerate the evolution, a reduced target concentration is typically used to increase "screening pressure" in repeated rounds [11-13], since lower concentration provides fewer binding sites and is helpful for strongly bound oligonucleotides surviving. However, decreasing target concentration is insufficient for increasing screening pressure in the whole comprehensive selection process. More screening pressures have to be considered. (1) Separation efficiency. High-efficiency separation determines the effective elimination scope of unbound and weakly sequences, which provides stronger screening pressure to speed up the evolution [4]. (2) Repeat rounds. Undesired sequences are eliminated in the continuous iterative interaction between the target and sub-libraries [14]. (3) Negative and counter selection. Negative or counter selection eliminates the non-specific binding sequences through competition [9]. (4) Target concentration. Either reducing the aim target concentration or increasing the counter target concentration provides higher screening pressure.

Most of the current selection works involve in employing efficient separation methods, reducing target concentration, introducing counter targets, or performing more screening rounds to strengthen screening pressure. However, these methods generally require multi-rounds selection and repeated PCR amplification, which causes serious preferential amplification and base mispairing [15-17]. Error reading of evolutional high-affinity sequence distorts the original aptamers candidates [18]. Although several reports have claimed one-round selection [14] or non-SELEX [19-21] can improve the screening efficiency by reducing PCR process, however, it has been suspected for the imperfection of screening pressure. Till now, it remains challenging to synchronously control multi-screening pressure in aptamer selection.

Herein, we present a novel high-efficiency aptamers picking strategy: one-round pressure controllable selection (OPCS), in which multiple screening pressure were integrated. OPCS scheme is depicted in Fig. 1. In OPCS process, two proteins (A and B) were co-incubated with one ssDNA library in a vial, in which each protein bound its favorable sequences specifically and formed its respective protein-ssDNA complex, meanwhile, one protein could supply/suffer the picking pressure of affinity and specificity to/from another, which eliminated weakly bound or unbound sequences for each other. Meanwhile, the screening pressure can be controlled through two approaches: Adjusted the proportion of target proteins, and dominant competition by introducing a predatory protein with high concentration. After incubation, the equilibrium mixture is injected into capillary and completed high-resolution capillary electrophoresis separation of unbound sequences and each complex [22-25] (Fig. 1). Through the collection of each complex fraction, PCR amplification and sequencing, aptamer candidates against protein A and B would be selected simultaneously.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Schematic of OPCS by two targets competition and one-run capillary electrophoresis (CE) separation. | |

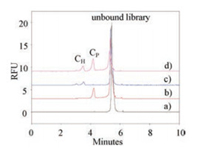

Human holo-transferrin (H-Tf) and platelet derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) were introduced as model proteins to perform the proof of concept of OPCS. In Fig. 2, the single peak of 0.2 μmol/L ssDNA library was observed at 5.28 min (curve a). After the addition of 0.4 μmol/L PDGF-BB or 0.4 μmol/L H-Tf in ssDNA library, complex peaks of CP peak at 4.17 min (curve b) and CH peaks of 3.0 and 3.5 min (curve c) were found, respectively, while the ssDNA peak decreased apparently. When H-Tf, PDGF-BB, and library were co-incubated with two proteins (curve d), both the CP and CH peaks appeared (curve d) indicated that two complexes of PDGF-BB/ssDNA and H-Tf/ssDNA were formed, thus simultaneous selection for two targets was feasible. It is worth noting that only H-Tf was incubated with ssDNA, there were two peaks appeared at 3.0 and 3.5 min, which was attributed to the formation of complexes with different mass-to-charge ratio.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Electropherograms of the separation of complexes and unbound library. Curve: a) 0.2 μmol/L ssDNA, b) a + 0.4 μmol/L PDGF-BB, c) a + 0.4 μmol/L H-Tf, d) a + 0.4 μmol/L H-Tf + 0.4 μmol/L PDGF-BB. CE separation conditions: 50 mol/L H3BO3/Na2B4O7 buffer, pH 8.7, 498 V/cm and 25 ℃. 5 s/0.5 psi injection, LIF detection with excitation/emission at 488/520 nm. | |

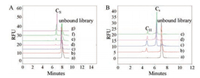

Further, the dynamic competitive binding of two target proteins was demonstrated. In Fig. 3A, keeping the concentration of H-Tf constant at 0.4 μmol/L accompanied by an increasing PDGF-BB concentration from 0.4 μmol/L to 1.2 μmol/L, and the results showed a reduction of CH peak, suggesting that PDGF-BB competitively bound ssDNA from H-Tf complex. Similarly, increasing H-Tf concentration also resulted in the peak area decrease of CP (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that different proportion of two proteins produces adjustable competing pressure. Apparently, the balance pressure of two targets can be generated by employing an equal concentration of two proteins, as a result, aptamers for two proteins can be obtained synchronously. The complexes of CH and CP fractions were collected separately (Fig. S1 in Supporting information). Through one PCR and high-throughput sequencing, seven aptamer candidates (Apt H1∼7) for H-Tf and seven for PDGF-BB (Apt P1∼7) were picked out (Table S1 in Supporting information), whose affinities and secondary structures were characterized and listed in Fig. S2 (Supporting information). The aptamers with the highest affinity for PDGF-BB (Apt P3, KD = 0.081 ± 0.018 μmol/L) and for H-Tf (Apt H6, KD = 0.050 ± 0.015 μmol/L) were synchronously obtained. To assess their specificity, their KD of two sequences of H-Tf and PDGF-BB against their competitor were determined. Fig. S3 (Supporting information) showed that Apt H and Apt P presented stronger affinity for its aim target far more than the competitor protein. Moreover, the target-aptamer binding showed excellent linearity (Fig. S4 in Supporting information). Above results suggested that balance pressure could be employed for two proteins selection with their equal concentration in one OPCS process.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Balanced competition binding of H-Tf, PDGF-BB and ssDNA library. (A) Keeping the constant concentration of H-Tf and increasing PDGF-BB (0.4–1.2 μmol/L). Curve: a) 0.2 μmol/L ssDNA + 0.4 μmol/L H-Tf, b) a + 0.4 μmol/L PDGF-BB, c) a + 0.8 μmol/L PDGF-BB, d) a + 1.2 μmol/L PDGF-BB. (B) Keeping the constant concentration of PDGF-BB and increasing H-Tf (0.4–1.2 μmol/L). Line: a) 0.2 μmol/L ssDNA + 0.4 μmol/L PDGF-BB, b) a + 0.4 μmol/L H-Tf, c) a + 0.8 μmol/L H-Tf, d) a + 1.2 μmol/L H-Tf. | |

Furthermore, if one target is at a dominant high concentration, more binding sites could be provided to compete for more ssDNA sequences. Hence, the target in lower concentration suffers a severe competitive pressure of the dominant competitor, which would facilitate the survival of the sequences with high affinity and specificity.

The dominant screening pressure can also be accomplished through introducing a predatory competitor. Single strand DNA-binding protein (SSB) is an ssDNA binding protein with a nanomolar KD with no sequence selectivity, which was used as the predator for H-Tf in OPCS. Fig. 4A showed that 4.0 μmol/L SSB can bind almost all the sequences when it was incubated with ssDNA library. When 0.2 μmol/L SSB and 0.4 μmol/L H-Tf were co-incubated, both complex peaks of CH and CS appeared separately at about 4.7 min and 6.2 min (Fig. 4B, curve b). Increasing SSB concentration to 1.0 μmol/L, ssDNA peak reduced significantly, and a large CS peak appeared accompanied with an apparent CH peak decrease (Fig. 4B, curve c). When adding another 2.0–3.0 μmol/L SSB (Fig. 4B, curves d and e), ssDNA peak disappeared with further increscent CS peak. With concomitant reducing of CH peak, SSB has shown extraordinary ability to combine ssDNA competitively.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Dominant competition binding of H-Tf, SSB, and ssDNA library. (A) SSB binding ssDNA library. Curve: a-g) 0.4 μmol/L ssDNA library + 0.0, 0.2, 0.4, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 μmol/L SSB; (B) H-Tf and SSB compete for binding ssDNA library. Line: a) 0.2 μmol/L ssDNA + 0.4 μmol/L H-Tf, b) a + 1.0 μmol/L SSB, c) a + 2.0 μmol/L SSB, d) a + 3.0 μmol/L SSB. | |

During the OPCS process, concentration ratio of SSB and H-Tf reached 15:2, under which the peak area of CH no longer decreased, suggesting that SSB competitive binding ssDNA from CH has reached the maximum. In this case, the remained ssDNA in complex CH has the potential of higher affinity and specificity. Collecting complex CH fraction (Fig. S5 in Supporting information) and performing one PCR amplification and sequencing, ten aptamer candidates of Apt H'1-10 were picked (Table S2 in Supporting information), they all have nanomolar KD values (Fig. S6 in Supporting information). Apt H'9 and Apt H'10 have extremely low KD values of 0.003 ± 0.001 μmol/L and 0.005 ± 0.001 μmol/L, respectively. Under the maximum competing pressure generated from the high concentration and predatory binding capacity of SSB, the affinity of Apt H' improved more than a 10-fold compared with that in balance competing pressure. Their KD of Apt H and Apt H' were shown in Figs. S2 and S6. Besides, the KD values of Apt H'1 and Apt H'2 for H-Tf in Fig. S7 (Supporting information) showed 1–2 orders of magnitude lower than that of SSB, which indicated their good specificity for H-Tf. The results demonstrated that employing a dominant competitor in OPCS process could improve the performance of aptamer candidates.

In this study, the OPCS strategy was proposed for the first time, which realized multi-screening pressure controllable through two approaches of balanced competition by equal protein concentration, and dominant competition by a predatory protein with high concentration. Target proteins H-Tf, PDGF-BB and SSB were used as model proteins, aptamers with high affinity and good specificity were obtained by one round selection. Besides, we have performed aptamers selection of Rec A, LZM, Cas9 and OGG1 (Fig. S8 in Supporting information) to confirm the feasibility and universality of OPCS. Our results show the OPCS strategy greatly improves the aptamers selection efficiency with advantageous of less consumption and time. This strategy not only performs a more effective way for aptamers selection, but shows great potential in other ligands or drugs selection.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors report no declarations of interest.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21675012, 21874010 and 21827810), and the Young Elite Scientist Sponsorship Program of Beijing Association for Science and Technology. There are no conflicts to declare.

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2020.10.018.

| [1] |

A.D. Ellington, J.W. Szostak, Nature 346 (1990) 818-822. DOI:10.1038/346818a0 |

| [2] |

C. Tuerk, L. Gold, Science 249 (1990) 505-510. DOI:10.1126/science.2200121 |

| [3] |

L. Bock, L. Griffin, J. Latham, et al., Nature 355 (1992) 564-566. DOI:10.1038/355564a0 |

| [4] |

L.P. Zhao, G. Yang, X.M. Zhang, et al., Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 48 (2020) 560-572. DOI:10.1016/S1872-2040(20)60012-3 |

| [5] |

Z.J. Wang, E.N. Chen, G. Yang, et al., Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 48 (2020) 573-582. DOI:10.1016/S1872-2040(20)60013-5 |

| [6] |

T. Wang, C. Chen, L.M. Larcher, et al., Biotechnol. Adv. 37 (2019) 28-50. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.11.001 |

| [7] |

J. Yan, H. Xiong, S. Cai, et al., Talanta 200 (2019) 124-144. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2019.03.015 |

| [8] |

Y. Zhang, B.S. Lai, M. Juhas, Molecules 24 (2019) 941. DOI:10.3390/molecules24050941 |

| [9] |

Y.X. Wu, Y.J. Kwon, Methods 106 (2016) 21-28. DOI:10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.04.020 |

| [10] |

M. Darmostuk, S. Rimpelova, H. Gbelcova, et al., Biotechnol. Adv. 33 (2015) 1141-1161. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.02.008 |

| [11] |

J. Tok, J. Lai, T. Leung, et al., Electrophoresis 31 (2010) 2055-2062. DOI:10.1002/elps.200900543 |

| [12] |

C. Ravelet, C. Grosset, E. Peyrin, J. Chromatogr. A 1117 (2006) 1-10. DOI:10.1016/j.chroma.2006.03.101 |

| [13] |

S.M. Krylova, A.A. Karkhanina, M.U. Musheev, et al., Anal. Biochem. 414 (2011) 261-265. DOI:10.1016/j.ab.2011.03.010 |

| [14] |

P. Bayat, R. Nosrati, M. Alibolandi, et al., Biochimie 154 (2018) 132-155. DOI:10.1016/j.biochi.2018.09.001 |

| [15] |

R. Yufa, S.M. Krylova, C. Bruce, et al., Anal. Chem. 87 (2015) 1411-1419. DOI:10.1021/ac5044187 |

| [16] |

M. Nakano, J. Komatsu, S.I. Matsuura, et al., J. Biotechnol. 102 (2003) 117-124. DOI:10.1016/S0168-1656(03)00023-3 |

| [17] |

T. Kanagawa, J. Biosci. Bioeng. 96 (2003) 317-323. DOI:10.1016/S1389-1723(03)90130-7 |

| [18] |

Z.J. Zhuo, Y.Y. Yu, M.L. Wang, et al., Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 (2017) 2142. DOI:10.3390/ijms18102142 |

| [19] |

S. Lisi, E. Fiore, S. Scarano, et al., Anal. Chim. Acta 1038 (2018) 173-181. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2018.07.029 |

| [20] |

C.H. Lam, N.E. Ward, J. Englehardt, Mol. Ther. 23 (2015) S57. |

| [21] |

M. Berezovski, M. Musheev, A. Drabovich, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (2006) 1410-1411. DOI:10.1021/ja056943j |

| [22] |

C. Zhu, G. Yang, M.G, et al., Biotechnol. Adv. 37 (2019) 107432.

|

| [23] |

A.T.H. Le, S.M. Krylova, M. Kanoatov, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 2739-2743. DOI:10.1002/anie.201812974 |

| [24] |

S.D. Mendonsa, M.T. Bowser, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126 (2004) 20-21. DOI:10.1021/ja037832s |

| [25] |

M. Berezovski, A. Drabovich, S.M. Krylova, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (2005) 3165-3171. DOI:10.1021/ja042394q |

2021, Vol. 32

2021, Vol. 32