b College of Biomass Science and Engineering, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610065, China;

c Department of Neurosurgery, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China;

d Key Laboratory of Leather Chemistry and Engineering of Ministry of Education, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610065, China

The precise closure of the wound is beneficial to accelerate the healing process and avoid delayed discharge of patients or other complications caused by poor wound healing [1-3]. For this reason, surgical suture is one of the most commonly used medical devices that can promote the healing by connecting body tissue together with little scar formation in the process of the wound healing. In order to meet different surgical needs, the ideal surgical suture should not only provide appropriate mechanical strength, moderate inflammatory response, anti-bacterial adhesion to prevent wound infection, and significant wound healing promotion, but should also permit easy operation and knot security during the surgery [4, 5]. However, up to now, none of the sutures can satisfy all of these requirements.

One of challenge for surgical suture is that its difficulty handling in minimally invasive surgery such as endoscopic and laparoscopic surgery, where it is hard to close incisions and lacunae with sewing and knotting [6]. When the suture is too tight, necrosis of the surrounding tissue may occur [7, 8], and also, the patients may suffer severe pain after the surgery. If the knot is too weak, scar tissue with poor mechanical properties will be formed, which even lead to hernia, and the bacteria may easily erode the loose wounds [9]. In an effort to overcome these hurdles, the application of a shape memory suture may be an enticing strategy, which can memorize its original tight shape initially, and then release appropriate stress triggered by an external stimulus [10]. For instance, the shape memory performance can be triggered by the body temperature, in other words, the thermal transition temperature (Ttrans) of a shape memory suture is preferably to be around or slightly above body temperature, so that transition from the temporary to the permanent shape could be initiated under physiological environment. When the shape memory suture was deformed into an elongated shape and fixed at low temperature, the intrinsic stress will be stored. Once the suture was applied on the wounds, it will shrink due to the trigger of body temperature, and the knots will tighten owing to the release of the stress [11]. Thus, the suture with near body temperature sensitive shape memory appears to be a promising candidate to improving handling in the surgery.

During the healing process of the surgical wound, bacteriainduced infection commonly occurs that results in surgical site infection (SSI) [12]. The underlying cause of persistent SSI in patients is due to the formation of bacterial colonization and subsequent biofilm in the surgical site [13, 14]. Even if they are treated with antibiotics, they can still produce local inflammation as a chronic infection [15, 16]. Therefore, as a possible carrier of bacteria, the suture itself should have the ability to resist bacteria. Indeed, surgical suture with antibacterial activity has attracted more and more research interests in recent years, such as poly(vinyl alcohol)/exfoliated grapheme fiber.

In general, there are two main antibacterial strategies that have been used for suture fabrication [17]. One is coating drug on the suture surface, and the other is incorporation drug within the suture matrix. Drug-coated sutures are available commercially that is easily be produced in low cost, while their major drawback is the difficulty in attaining efficient drug loading and poor control over the drug release. In contrast, drug-incorporated sutures have advantages of stable and high efficient drug loading. Nevertheless, the harsh processing conditions are normally involved in the production of this type suture. For example, melt spinning is the most common technique to fabricate commercial sutures, but the use high temperature to melt and process the raw material of the suture would inactivate the loaded drugs. Similarly, electrospinning is capable of stable drug loading and controlled release, the inherent low mechanical property of the prepared suture, however, requires harsh post-processing conditions to enhance its strength which would also be harmful to the activities of the loaded drugs [18].

For preparation of shape memory surgical suture, polyurethane is a promising materials due to its so-called microphaseseparated heterogeneous structure where the hard segment plays a role in pivoting point for shape recovery with a higher thermal transition temperature, while the soft segment suggests to be responsible for absorbing external stress [19, 20]. In this work, we report a facile scalable strategy to fabricate surgical sutures possessing both shape memory and antibacterial functions for wound healing. First, shape memory polyurethane (SMPU) block copolymers composed of diphenylmethane diisocyanate (MDI), polycaprolactone (PCL), and 1, 4-butanediol (BDO) as a chain extender were synthesized by a two-step process (Fig. S1 in Supporting information), in which the one with a Ttrans near body temperature was obtained by adjusting the mole ratio of the hard/soft segment, and then the shape memory surgical sutures containing polyhexamethylene biguanide hydrochloride (PHMB) as a model drug for antibacterial activity were fabricated by a facile scalable one-step wet-spinning approach, where PHMB was directly dissolved in the coagulation bath that enable its loading into the sutures through the dual diffusion during the phase separation (Scheme 1).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. One-step wet-spinning of surgical sutures with shape memory function and antibacterial activity. | |

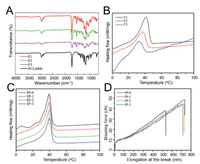

Aiming at preparing a SMPU with suitable Ttrans, i.e., near body temperature, the Tm of the synthesized SMPU was optimized by tuning the molar ratio between the soft and hard segments, and the main compositions and thermal properties are summarized in Table S1 (Supporting information). Three types of SMPU (F1, F2 and F3) were synthesized in terms of the hard segment content, particularly including 20%, 35% and 50%. The structure and thermal properties were investigated by FTIR, DSC, and the resulting curves are presented in Fig. 1. For FTIR, the wide peaks at around 3250 cm-1 to 3400 cm-1 of F1, F2 and F3 curves in Fig. 1A represent the stretching vibration of -NH groups in SMPU, while those cannot be observed in PCL curve. Additionally, the sharp peaks at around 1718 cm-1 represents the typical C=O stretching vibration in SMPU. Thus, it can be inferred that three types of SMPU have been successfully synthesized according to our previous studies [21]. The thermal degradation behavior of the SMPU was also investigated by TGA measurement shown in Fig. S2A (Supporting information), and the results showed that there was no significant difference among the three types of SMPU, suggesting that the thermal degradation of synthesized SMPU mainly depends on the molecular structure and components, rather than the ratio between the soft and hard segments. However, the Tm of SMPU is highly dependent on the crystallization of the soft segments, i.e., the PCL chains, thus DSC was employed to monitor the crystallization behaviors of F1, F2 and F3. The testing program is shown in Fig. S2B (Supporting information), where the thermal history was eliminated in the first heating process, and the Tm was recorded in the second heating process. It was found that three different melting points were measured, 31.2, 35.2 and 41.3 ℃ for F1, F2 and F3, respectively (Fig. 1B). Therefore, as expected, such SMPU, F3 with a suitable Ttrans slightly above the body temperature, was successfully obtained by optimizing the content of hard segment, and thus F3 was further applied to fabricate the shape memory sutures.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. The FTIR spectra (A) and DSC curves (B) of the SMPU. The DSC (C) and stretching (D) curves of the sutures. | |

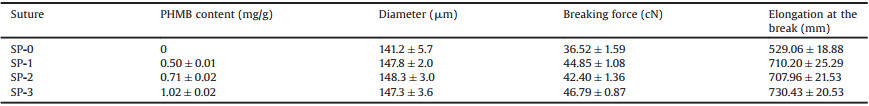

The surgical suture was then fabricated by a facile scalable onestep wet-spinning approach. The spinning parameter is detailed in Table S2 (Supporting information). PHMB was dissolved in the coagulation bath and the dual diffusion between the coagulation bath and the DMAc in the spinning solution resulted in phase separation and forming the fiber as suture containing PHMB. To load different amount of PHMB into the suture, various concentrations of PHMB in the coagulation bath were used. As expected, Table 1 shows the PHMB content in the fabricated sutures (SP-0, 1, 2, 3) was increased with the increasing concentration of the PHMB in the coagulation bath. The DSC curves of the sutures are shown in Fig. 1C. The four sutures have similar melting points that remain near body temperature, indicating that the loaded PHMB did not change the crystallization behavior of PCL segments. In addition, desirable mechanical property is one of prominent features for suture in practical applications. As shown in Fig. 1D and Table 1, it was interesting to find that the PHMB loaded sutures exhibited better mechanical property than that of suture without PHMB. The possible reason is the toughening effect of PHMB in virtue of the possible couplings between biguanide and carbamate groups which led to the enhanced tension resistance [22].

|

|

Table 1 Characteristics of the sutures. |

The SEM images of the sutures are shown in Fig. S3 (Supporting information). The surface morphology shows that their surfaces are almost smooth, even though some shallow grooves along fiber directions can be observed. The cross-sectional morphology displays massive pores feature as a result of phase separation. In addition, there was no significant difference among the four sutures in terms of the surface and cross-sectional morphologies.

Figs. 2A and B show the typical macroscopic images in the course of shape memory testing process which is a classical thermal one-way shape memory procedure, and three main steps were involved, including first heating for stretching, cooling for fixation, and heating again for recovery. According to the calculation results of shape fixation (Rf) and recovery (Rr) ratios, all the sutures possess desirable Rf and recovery Rr, which are around 85% and 95%, respectively. In addition, it can be found that the shape memory property becomes better with increasing PHMB concentration in the coagulation bath, especially the Rf. The improvement can be possibly ascribed to the coupling interaction between PHMB and SMPU. In virtue of such desirable shape memory capacity, the suture can be deformed before the operation, and the deformed shape can recover to the original shape triggered by body temperature. Particularly in wound healing, immediate force may possibly produce much pain to the patients. In contrast, the gradual recovery may benefit patients suffering less pain and the wound recovery.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. The typical macroscopic images in the course of shape memory testing (A and B); Antibacterial performance of the sutures (C). | |

A surgical suture with potent antibacterial capacity is crucial to the wound healing, especially the suture applied for the festering wound. The antibacterial capacity of SP-1, SP-2 and SP-3 was evaluated through flat colony counting method. It can be seen from Fig. 2C that both negative and positive bacteria spread fully on the plates of SP-0, comparatively, much less bacterial colonies present on the plates of SP-1, SP-2 and SP-3, in which SP-3 shows the strongest inactivating activity against both negative and positive bacteria. Definitely, the strong antibacterial activity of SP-3, compared with SP-1 and SP-2, is derived from the highest loading amount of PHMB which contains biguanide-rich structure with strong cationic feature that can directly bind to the negatively charged phosphate groups on the cell wall, and thus disrupting the integrity of the cell, eventually leading to bacterial cell death [23]. Based on its better antibacterial activity, SP-3 was selected for the next cell and animal studies.

Prior to in vivo study, it is necessary to test the biocompatibility of the suture. The cytotoxicity of SP-0 and SP-3 was detected by alamar blue test using L929 cells. According to ISO 10993, samples with cell survival rate of more than 75% can be regarded as noncytotoxicity. As shown in Fig. 3A, the cell viability of SP-0 and SP-3 was more than 90% on both the 1st and 3rd day, and there was no significant difference from the blank control, indicating that there was no cytotoxicity for the both two sutures. In the subcutaneous implantation test, there was no obvious tissue rejection for the two sutures after 7 days post-implantation (Fig. 3B), and also, the tissue inflammation scores of the SP-0 and SP-3 sutures were 2 points and 1 point, respectively, indicating that the two sutures have a moderate inflammatory response.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (A) Cytotoxicity analysis using Alamar blue test. (B) The inflammatory cells were highlighted (c, d) to evaluate the inflammatory response in the wounds of SP-0 and SP-3 at day 7. Inflammatory cells were highlighted using Image J software. | |

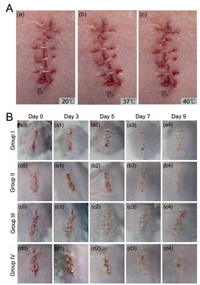

In vivo shape memory performance was carried out to test the self-tightening of the suture. Fig. 4A shows the shape memory function of SP-3 suture under the temperature of 20 ℃, 37 ℃ and 40 ℃, respectively. With the temperature increased, the suture formed a tighter knot on the incision. Therefore, it can be concluded that SP-3 suture may be utilized as a promising material for suturing incisions in minimally invasive surgeries.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (A) SP-3 suture for wound closure: The photos show the shrinkage of the suture with temperature increase (a–c). (B) Images showing the wound healing process. | |

The effect of SP-3 suture on the wound healing was evaluated by a mouse skin suture-wound model. Group Ⅲ and group Ⅳ were infected with bacteria smear while group Ⅰ and group Ⅱ without this handling. Fig. 4B shows the wound healing of the four groups on day 0, 3, 5, 7, 9 after the surgery. On day 0, there was no abnormality in each group. On day 3, the skin around the wound in group Ⅲ was red and swelling, while the other three groups did not show this phenomenon, indicating that the bacteria smear induced wound infection, since red swelling is a typical manifestation of inflammation after wound infection. With the time prolonged, the wounds in group Ⅰ, Ⅱ and Ⅳ were healing gradually without infection, whereas the ones in group Ⅲ remains showed infection signs such as necrosis on day 9. During the whole healing process, although both in the presence of bacteria, the wounds in group Ⅳ were not as red and swollen as in group Ⅲ, and finally exhibited better healing when compared to that in group Ⅲ. Overall, it revealed that SP-3 suture is capable of antibacterial activity and promoting wound healing.

One of the most common signs of infection is an increase of body temperature (BT) [24], and thus the BT of the mice was observed by infrared thermal imager every day (Fig. S4 in Supporting information). Consistently, the average temperature of the mice at every day (1–9) in group Ⅲ was higher than those in other three groups, and the BT of the mice in group Ⅳ was significantly lower than that in group Ⅲ, indicating once again that SP-3 suture has good antibacterial activity.

Histology of the suture neighboring tissue was examined by H & E staining (Fig. 5). The results showed that, without bacteria smear, there was no obvious inflammatory response in group Ⅰ and Ⅱ on both day 3 and day 7. However, with bacteria smear, there were a large number of macrophages and neutrophils around the suture hole in group Ⅲ on both day 3 and day 7, indicating that the aggravated inflammatory reaction was induced by the bacterial infection. On the contrary, there was no obvious inflammatory cell around the suture hole in group Ⅳ, suggesting that SP-3 suture is beneficial to anti-inflammatory.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. H & E stained cross-sections of the suture site skin of four groups on the 3rd and 7th days after operation. Scale bar: 50 μm. | |

To further investigate the anti-inflammatory effect of the suture, the expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β was determined by immunohistological staining. As shown in Fig. S5 (Supporting information), both the expression of TNF-α and IL-1β in group Ⅰ, Ⅱ and Ⅳ was significantly lower than that in group Ⅲ on day 3 and 7. Proinflammatory cytokines are produced in the early stages of inflammation. TNF-α and IL-1β regulate the expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules, which are necessary for the aggregation of inflammatory cells to the injured site. Appropriate expression of TNF-α and IL-1β is crucial to active the inflammatory reaction for body defense such as bacteria-induced infection. Nevertheless, continuous high expression of the two cytokines is harmful to body restore. Here, combination of the histology and immunohistology results, it can conclude that the group Ⅲ showed a remarkable and continuous inflammation reaction due to the bacteria smear and SP-3 suture is capable of reducing this reaction.

In conclusion, we successfully fabricated surgical sutures with shape memory function and antibacterial activity for wound healing using a facile scalable one-step wet-spinning strategy. SMPU with a Ttrans near body temperature was first synthesized and characterized by FTIR, DTG and DSC, and then the surgical sutures containing different amount of PHMB were fabricated and characterized by their morphology, mechanical properties, in vitro shape memory function, and antibacterial activity. The optimized suture was further evaluated by animal studies and the results confirmed that the suture was capable of shape memory and inactivating bacteria, and thus promote wound healing. Taken together, our work demonstrated that a facile scalable one-step wet-spinning strategy for fabrication of surgical suture was developed, which offers great promise for clinical applications in wound healing.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51803128), Opening Project of Key Laboratory of Leather Chemistry and Engineering (Sichuan University), Ministry of Education (No. 20826041C4159), Sichuan Science and Technology Programs (Nos. 2017SZYZF00009, 19YJ0126), Strategic Project of Lu Zhou Science & Technology Bureau (No. 2017CDLZ-S01).

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary materialrelated tothis article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2019.11.006.

| [1] |

F.E. Muysoms, S.A. Antoniou, K. Bury, et al., Hernia 19 (2015) 1-24. DOI:10.1007/s10029-014-1342-5 |

| [2] |

J. Huang, L. Chen, Z. Gu, et al., J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 15 (2019) 1357-1370. DOI:10.1166/jbn.2019.2815 |

| [3] |

J. Huang, L. Chen, Q. Yuan, et al., J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 15 (2019) 1371-1383. DOI:10.1166/jbn.2019.2814 |

| [4] |

K. Shao, B.Q. Han, J.N. Gao, et al., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B:Appl. Biomater. 104 (2016) 116-125. DOI:10.1002/jbm.b.33307 |

| [5] |

F. Alshomer, A. Madhavan, O. Pathan, et al., Curr. Med. Chem. 24 (2017) 215-223. DOI:10.2174/0929867324666161118141724 |

| [6] |

A. Abiri, O. Paydar, A. Tao, et al., Surg. Endosc. 31 (2017) 3258-3270. DOI:10.1007/s00464-016-5356-1 |

| [7] |

D.J. Kim, W. Kim, Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 12 (2016) 77-79. |

| [8] |

Z.Z. Sheng, X. Liu, L.L. Min, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 28 (2017) 1131-1134. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2017.03.033 |

| [9] |

Y. Tsukamoto, H. Oshima, T. Katsumori, et al., Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 45 (2018) 474-476. |

| [10] |

K. Kapoor, A.M. Bhandare, M.M.J. Farnham, et al., Resp. Physiol. Neurbi. 226 (2016) 51-62. DOI:10.1016/j.resp.2015.11.015 |

| [11] |

R. Duarah, Y.P. Singh, P. Gupta, et al., Biomed. Mater. 13 (2018) 045004. DOI:10.1088/1748-605X/aab93c |

| [12] |

J.M. Xia, W.J. Wang, X. Hai, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 30 (2019) 421-424. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2018.07.008 |

| [13] |

J. Dhom, D.A. Bloes, A. Peschel, et al., J. Orthop. Res. 35 (2017) 925-933. DOI:10.1002/jor.23305 |

| [14] |

S. Kathju, L. Nistico, I. Tower, et al., Surg. Infect. (Larchmt) 15 (2014) 592-600. DOI:10.1089/sur.2013.016 |

| [15] |

J.L. Del Pozo, Expert Rev. Anti. Ther. 16 (2018) 51-65. DOI:10.1080/14787210.2018.1417036 |

| [16] |

R. Roy, M. Tiwari, G. Donelli, et al., Virulence 9 (2018) 522-554. DOI:10.1080/21505594.2017.1313372 |

| [17] |

S. Padmakumar, J. Joseph, M.H. Neppalli, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Int. 8 (2016) 6925-6934. DOI:10.1021/acsami.6b00874 |

| [18] |

T.T. Wu, M.Z. Ding, C.P. Shi, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 617-625. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2019.07.033 |

| [19] |

K.H. Wu, B.D. Yan, S.Y. Yu, Mater. Express. 9 (2019) 245-254. DOI:10.1166/mex.2019.1493 |

| [20] |

L. Yang, Z.X. Wang, T. Zhao, et al., Mater. Express 8 (2018) 199-210. |

| [21] |

X.Q. Yin, Y. Wen, Y.J. Li, et al., Front. Chem. 6 (2018) 490. DOI:10.3389/fchem.2018.00490 |

| [22] |

F. Li, Y. Liu, C.B. Qu, et al., Polymer 59 (2015) 155-165. DOI:10.1016/j.polymer.2014.12.067 |

| [23] |

L.W. Place, S.M. Gulcius-Lagoy, J.S. Lum, Colloids Surf. A 530 (2017) 76-84. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2017.07.004 |

| [24] |

O. Nomura, T. Ihara, H. Sakakibara, et al., Pediatr. Int. 61 (2019) 449-452. DOI:10.1111/ped.13831 |

2020, Vol. 31

2020, Vol. 31