b CAS Key Laboratory of Synthetic Chemistry of Natural Substances, Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai 200032, China

Since the enormous potential of fluorochemical cleaning products were highlighted by 3M company in the 1950s, fluorosurfactants have been extensively exploited over 200 applications in clothing fabrics, electroplating, fire fighting foams, food packaging, petroleum, textile, along with multibillion dollar industries [1, 2]. Aqueous film forming foams (AFFFs), an extinguishing agents to put out polar (alcohols, ketones, esters) or nonpolar (hydrocarbons) solvent fire, is one of the most important applications of fluorinated surfactants. The very low apparent density of AFFFs allows them to be spread at the surface of burning liquids [3, 4]. The evaporation of the water resulting from the heat reduces the intensity of the fire and the foam generates a water film at the surface of the solvent which prevents the emission of flammable vapors. In addition, after extinction, the foam prevents the risk of fire burnback [4]. AFFFs are often found where there are large volumes of flammable liquids and the potential for a fire exists. For example, AFFFs are found at military bases, fire departments, and airports [5, 6]. Fluorinated surfactants have outstanding chemical and thermal stabilities, and play a crucial role in the formation of the water film at the surface of the solvent.

Featuring the most stable C-F single bond [7], perfluoroalkyl substances recently have awakened the concern in human health (the presence and persistency in fetuses, newborn babies, human milk, and human blood, etc.) and social environment [8]. Among of them, fluorinated surfactants that chain lengths of C8 or longer have been revealed more possible to be bioaccumulative and potently toxic [9]. According to the PFOA Stewardship Program, both industrial and academic sectors have set about the deploitation of short-chain based fluorosurfactants (Rf < C6–7) to mitigate their persistent nature of pollution [10].

Hexafluoropropylene dimer containing only C5 main chain is a representative template to synthesize various branched fluorinated surfactants [11-13]. The short chain length makes it is an idea material to preparing non-bioaccumulable alternatives to PFOA/PFOS. On the other hand, hyperbranched hydrocarbon surfactants possess fluorocarbon-like low surface energies than conventional straight chain ones [14], and branched fluorinated surfactants show more efficient at a relatively lowconcentration than common linear fluorosurfactants [15, 16]. As such, the import of branched chain is a valid strategy to develop surfactants with high performance. So far, to the best of our knowledge, most studies just focused on the preparation of new compound derived from hexafluoropropylene oligomer [11-13, 15-17], no report has discussed the application of this kind of branched fluorinated surfactants in the AFFFs field. However, years of employing AFFFs in a variety of situations has resulted in these fire-fighting foam components being directly released to the environment and the contamination of groundwater [5].

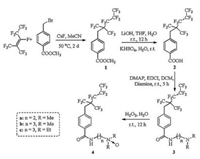

In view of those facts mentioned above, this study proposed a novel serious of fluorosurfactants with branched short fluorinated tails as hydrophobic groups, ammonium oxide as polar groups and benzene ring as space units, respectively (Scheme. 1). Four steps led to the compound 4. First, methyl 4-(bromomethyl)benzoate was changed to compound 1 by a nucleophilic substitution reaction. Second, saponification of the ester 1 followed by acidification led to the carboxylic acid 2. Then, conversion of the acid 2 into the amide 3 was carried out by treating with EDCI and appropriate diamine. Finally, the title compound 4 was obtained by oxidation with hydrogen peroxide. All the chemicals, instruments used in this work, the experimental details and the key spectra are presented in the Supporting information.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Synthetic route for the branched fluorosurfactants. | |

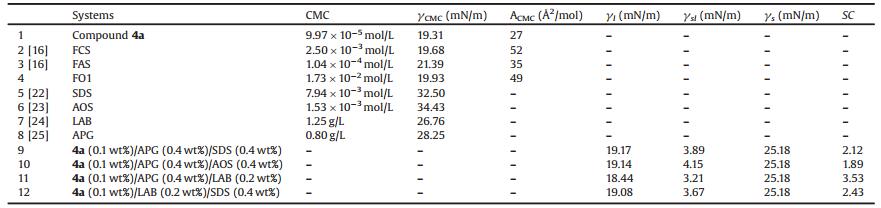

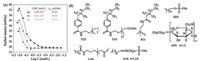

The surface or interface tension of surfactants in individual form or mixed system was tested by the Wilhelmy plate method using a Kruss K100 tensiometer at 25 ℃. All the values were the average of three-run measurements. The change trend of surface tension for 4a–c in aqueous solution upon various concentrations is presented in Fig. 1A. All the CMC of 4a–c are below 1.0 × 10-4 mol/L and the surface tension at CMC (γCMC) are below 20 mN/m. Compounds 4b and 4c showed better surface activity than 4a, for instance, the CMC of 4b reduced from 9.97 × 10-5 mol/L to 5.51 × 10-5 mol/L at 298 K, along with the simultaneous decrease of γCMC from 19.31 mN/m to 18.70 mN/m. All the values of surface properties of compounds 4a–c are lower than that of sodium perfluorooctanoate (about 24.7 mN/m at the CMC of 3.1 × 10-2 mol/L) [18]. Comparisons of surface properties with several fluorinated surfactants (Fig. 1B and synthetic procedure of FO1 see Supporting documents) synthesized from hexafluoropropylene dimmer were summarized in Table 1. The results showed that the compounds we synthesized in this work exhibited the best ability and efficiency to reduce the surface tension of water (The γCMC of compound 4a, FCS and FAS, are 19.31 mN/m, 19.68 mN/m, and 21.39 mN/m, respectively, meanwhile, the CMC values of them are 9.97 × 10-5 mol/L, 2.50 × 10-3 mol/L, 1.04 × 10-4 mol/L, respectively).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. (A) Surface tension measurements of 4a–c at 25 ℃. (B) Structures of FCS/FAS/FO1 and SDS/AOS/APG/LAB. | |

|

|

Table 1 Static surface and interface properties of different water solutions at 25 ℃. |

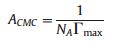

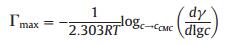

It is generally acknowledged that lower interfacial molecular areas indicate improved interfacial packing ability [19], the abilities of surfactants to form packed layers on water can be evaluated by the values of ACMC (minimal area per molecule). The occupied area per molecule (ACMC) was derived from the static surface tension vs. log(c) curves through the following equation [20, 21]:

|

(1) |

where NA is the Avogadro's number and Γmax is the surface excess concentration as defined by:

|

(2) |

where R is a gas constant, T is the absolute temperature.

As seen in Table 1, compound 4a possessed much lower CMC (9.97 × 10-5 mol/L) and ACMC (27 Å2/mol) than FO1, suggesting that the rigid spacer unit (aromatic spacer) would promote micellization and packing.

AFFFs usually contain fluorinated surfactants, hydrocarbon surfactants, organic solvents, and so on. SDS/AOS/APG/LAB (Fig. 1B) are the most frequently used hydrocarbon surfactants in foam concentrates, determining the formation of foams as well as the reduction of the interfacial tension [3, 4]. We selected compound 4a to mix with SDS, AOS, LAB or APG to exam the potential application of compounds 4a–c in AFFFs.

Two anion hydrocarbon surfactants sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and sodium C14-16 olefin sulfonate (AOS) were selected. Effects of the total concentration of mixed surfactant with different mass ratios on the surface tension are given in Figs. 2A and B. The surface activities of the pure surfactants are summarized inTable 1. Obvious "synergistic" interaction is observed that the CMC decreased with elevated mass ratios of SDS or AOS to 4a, while the value of γCMC for mixed systems almost retained unchanged compared to single 4a solution.It is noteworthy that when the mass ratio of 4a to SDS is 1:1, the γCMC is 18.83 mN/m and the CMC is 1.78 × 10-5 mol/L, which are both lower than that of single 4a or SDS.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (A) Effect of the total concentration of mixed 4a and SDS with different mass ratios on the surface tension at 25 ℃. (B) Effect of the total concentration of mixed 4a and AOS with different mass ratios on the surface tension at 25 ℃. (C) Effect of the concentration of LAB on the surface tension of the mixed 4a and LAB at 25 ℃. (D) Effect of the concentration of APG on the surface tension of the mixed 4a and APG at 25 ℃. | |

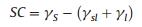

The combination systems of 4a (0.1 wt%) with zwitterionic hydrocarbon surfactant lauroylamide propylbetaine (LAB) and nonionic hydrocarbon surfactant alkyl polyglycoside (APG) were further evaluated (Figs. 2C and D). It reveals that a conspicuously low surface tension, which were all below 18.50 mN/m in selected concentration range. In terms of LAB, the lowest surface tension reached to 17.90 mN/m when the concentration is 0.3 wt%. The incorporation of APG exhibited a better "synergistic" interaction than LAB, along with all surface tensions lower than 18.00 mN/m and lowest surface tension of 17.31 mN/m at 0.4 wt%. Compounds 4a–c not only have great micellization and packing abilities but also have remarkable compatibility to various types of hydrocarbon surfactants, these excellent properties make the application in AFFFs possible. The multicomponent system of AFFFs places the demand of good synergistic effect with additives for fluorosurfactants to guarantee the ability to form water film at the interface. This water film formation occurs when the spreading coefficient (SC) of the foaming solution is positive. That spreading coefficient is defined in Eq. (3) [26]:

|

(3) |

where γs is the surface tension of the solvent; γsl is the interfacial tension between the solvent and the foaming solution and γl is the surface tension of the aqueous foaming solution.

The use of fluorinated surfactants provides the foaming solution with a particularly low surface tension (γl) and hydrocarbon surfactants reduce the foaming solution/solvent interfacial tension (γsl). Without an appropriate choice of these two types of surfactants, the spreading coefficient would be negative and extinction impossible. AFFFs usually contains more than one hydrocarbon surfactant to achieve the idea effect [3, 4]. Table 1 listed the ternary systems which were comprised by 4a and two hydrocarbon surfactants. The recipes were designed according to the consequences in the binary systems. The γs of the cyclohexane, the γl of the aqueous solution and the γsl between the solvent and the aqueous solution were measured and presented in Table 1. On the basis of resulted surface tension, all the four systems showed better surface activities than single 4a aqueous solution and the calculated spreading coefficients were positive. The foaming solutions were dropped on cyclohexane to exam the spreading abilities. The results of spreading tests showed all the four aqueous solution could form a water film at the interface of cyclohexane. The excellent performances both in binary and ternary systems of our well-designed compounds further verified 4a–c can be potential surfactants candidates to develop practical AFFF materials.

In this work, we successfully synthesized three novel branched fluorosurfactants starting from perfluoro-2-methyl-2-pentene. The introduction of aromatic spacer unit can promote micellization in aqueous solution and packing at the air-water interface. The asobtained compounds not only exhibited excellent ability to reduce surface tension to below 20.00mN/m but also showed remarkable efficiency to reduce the surface tension of water (the CMC values of compounds 4a–c inwaterwereless than 1.0 × 10-4mol/L at 298K). The CMC decreased obviously with the increased mass ratios of SDS or AOS to 4a, while the γCMC of mixed systems were barely changed. Moreover, the combined systems showed even better synergistic interaction when 4a was mixed with APG or LAB, along with surface tension less than 18.00mN/m at several mixed conditions. The surface tensions of ternary systems are also less than single 4a solution. The phenomenon of the foaming solution spread on the cyclohexane means compounds 4a–c are promising fluorosurfactants to design new formulations in fire-fighting field.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 2167020782) and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No. 15DZ2281500).

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2018.04.017.

| [1] |

M.R. Porter, Handbook of Surfactants, 2nd ed., Blackie Academic & Professional, London, 1994.

|

| [2] |

A. Czajka, G. Hazell, J. Eastoe, Langmuir 31 (2015) 8205-8217. DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b00336 |

| [3] |

M. Pabon, J.M. Corpart, J. Fluorine Chem. 114 (2002) 149-156. DOI:10.1016/S0022-1139(02)00038-6 |

| [4] |

M.L. Carruette, H. Persson, M. Pabon, Fire Technol. 40 (2004) 367-384. DOI:10.1023/B:FIRE.0000039164.88258.1d |

| [5] |

C.A. Moody, J.A. Field, Environ. Sci. Technol. 34 (2000) 3864-3870. DOI:10.1021/es991359u |

| [6] |

C.A. Moody, J.W. Martin, W.C. Kwan, D.C. Muir, S.A. Mabury, Environ. Sci. Technol. 36 (2002) 545-551. DOI:10.1021/es011001+ |

| [7] |

M.M. Montero-Campillo, N. Mora-Diez, A.M. Lamsabhi, J. Phys. Chem. A 114 (2010) 10148-10155. |

| [8] |

C.A. Ng, K. Hungerbuehler, Environ. Sci. Technol. 49 (2015) 12306-12314. |

| [9] |

R. Renner, Environ. Sci. Technol. 40 (2006) 12-13. |

| [10] |

T. Schuster, J.W. Krumpfer, S. Schellenberger, et al., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 428 (2014) 276-285. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2014.04.051 |

| [11] |

S.V. Kostjuk, E. Ortega, F. Ganachaud, B. Améduri, B. Boutevin, Macromolecules 42 (2009) 612-619. DOI:10.1021/ma8012338 |

| [12] |

L. Chen, H. Shi, H. Wu, J. Xiang, Colloids Surf. A 384 (2011) 331-336. |

| [13] |

S. Peng, M.H. Hung, J. Fluorine Chem. 133 (2012) 77-85. DOI:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2011.10.007 |

| [14] |

M. Sagisaka, T. Narumi, M. Niwase, et al., Langmuir 30 (2014) 6057-6063. DOI:10.1021/la501328s |

| [15] |

W. Dmowski, H. Plenkiewicz, K. Piasecka-Maciejewska, et al., J. Fluorine Chem. 48 (1990) 77-84. |

| [16] |

M. Sha, R. Pan, P. Xing, B. Jiang, J. Fluorine Chem. 169 (2015) 61-65. DOI:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2014.11.005 |

| [17] |

M. Sha, R. Pan, L. Zhan, P. Xing, B. Jiang, Chin. J. Chem. 32 (2014) 995-998. DOI:10.1002/cjoc.201400377 |

| [18] |

Q. Zhang, Z. Luo, D.P. Curran, J. Org. Chem. 65 (2000) 8866-8873. |

| [19] |

A. Leiva, M. Urzúa, L. Gargallo, D. Radić, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 299 (2006) 70-75. |

| [20] |

D.J. Holt, R.J. Payne, W.Y. Chow, C. Abell, J. Colloid InterfaceSci. 350 (2010) 205-211. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2010.06.036 |

| [21] |

T.H.V. Ngo, C. Damas, R. Naejus, R. Coudert, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 400 (2013) 59-66. |

| [22] |

M. Dahanayake, A.W. Cohen, M.J. Rosen, J. Phys. Chem. 90 (1986) 2413-2418. DOI:10.1021/j100402a032 |

| [23] |

J. Wang, W. Wang, F. Wang, Z. Du, China Surfactant Deterg. Cosmet. 39 (2009) 162-165. |

| [24] |

H. Ju, T. Tao, Y. Jiang, Y. Wang, Text. Auxiliaries 34 (2017) 12-15. |

| [25] |

J. Han, L. Ma, Q. Yang, W. Zhang, China Surfactant Deterg. Cosmet. 45 (2015) 505-508. |

| [26] |

W.D. Harkins, A. Feldman, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 44 (1922) 2665-2685. DOI:10.1021/ja01433a001 |

2018, Vol. 29

2018, Vol. 29