An atomic cluster consisting of three to a few tens of atoms is an intermediate state of matter. The novelty of an atomic cluster mostly arises from the fact that its physical and chemical properties usually explain the transition from a single atom to the solid-state, which has been proved and studied by modern experimental techniques [1]. The science of clusters is a highly interdisciplinary field concerning astrophysicists, atomic physicists/ chemists, solid-state physicists, nuclear physicists and as well as plasma physicists. Because of the strong dependence of its electronic properties on its size and crystal structure, atomic clusters provide exciting prospects for designing new materials. It may also serve as a model to elucidate the chemically reactive sites on the surface. Studies of the chemistry and physics that occurs on the surface of the atomic cluster provide a new way to investigate surface reaction processes. This research may generate further insight into the fundamental steps that make up the complicated chemical processes taking place on the solid surface.

Silicon (Si) atomic clusters (Sin with n < 12) have been extensively investigated owing to their wide applications in nanoelectronic devices [2, 3] and as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) [4]. Previous results demonstrated that Si6 and Si10 clusters are energetically stable [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. In contrast, as a congener, the investigation of electronic properties of germanium (Ge) atomic clusters was rarely reported. Ge is one of the most important alternatives to Si applied either in semiconducting electronic devices or LIBs, since it has superior electron/hole and lithium (Li) ion mobility at room temperature than Si because of its lower band gap [10, 11, 12].

Owing to its high theoretical capacity (1623 mA h/g) by formation of Li4.4Ge with Li and high volumetric capacity of 7366 A h/L, Ge has been widely utilized as the anode electrode for LIBs [13, 14]. However, the dynamic process and electronic interaction between Li and Ge atoms still remain unknown. An understanding of the structure and electronic properties of Lialloyed Ge atomic cluster is thus helpful to explain the phenomena such as surface chemistry and reaction processes during Li is alloying with Ge electrode, since in the atomic cluster most of the atoms can be regarded as sitting at the surface. The aim of this article is to study the effects of surface alloying of the Li atom on the crystal structure and the electronic properties of the Ge10H16 cluster. This knowledge can be very useful in understanding the chemical reactions of Li with Ge when Ge is applied as an anode material for LIBs.

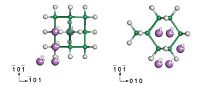

2. Model and calculation methodThe atomic structure of the Ge10H16 cluster is shown in Fig. 1, which was then placed in a cubic cell with periodic boundary situations to investigate the influence of Li alloying on its electronic and crystal structures. The Li atom was located firstly at the tetrahedral (Td) sites of the cluster due to energetical priority. Then, we calculated five different Td sites for the locations of Li atom as shown in Fig. 2. We discussed the Mulliken populations including the atomic populations and band populations, calculated the density of states (DOS), partial DOS (PDOS), and difference in charge density. Finally, we employed complete linear synchronous transit (LST)/quadratic synchronous transit (QST) calculations with convergence thresholds to study the root mean square (RMS) forces on the atoms lower than 0.05 eV/Å.

The calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio simulation Package (VASP) based on the density functional theory (DFT) with generalized gradient approximation (GGA) [15]. The k-point mesh of 1 × 1 × 1 (Gamma) was generated by the Monkhorst-Pack sampling scheme. To eliminate the interactions, the space between the cluster and its replica was beyond 17 Å. Ultrasoft pseudopotential with a plane wave cutoff energy of 330 eV was applied to model the interactions between core electrons and ions. Valence state electrons studied in this work include Ge 4s24p2, H 1s1, and Li 1s22s1. The Broyden-Fletcher- Goldfarb-Shanno (BFGS) algorithm is utilized for relaxing the internal coordinates with the convergence criterion for force less than 0.01 eV/ Å and the energy change 5 × 10-6 eV. During geometric optimization, the stress was less than 0.02 GPa and the maximum displacement was 0.0005 Å.

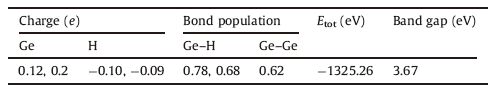

3. Results and discussionThe full geometric optimization of the atomic cluster results in a tetrahedral structure as shown in Fig. 1, in which the Ge-Ge bond length is 2.44 Å, a value close to the experimental Ge-Ge bond length found in amorphous Ge nanoparticles (2.46 Å) [16]. The distances of Ge-H bonds are 1.551 Å for Ge3-Ge-H and 1.546 Å for Ge2-Ge-H2. Then we calculated the Mulliken charge, bond population, and band structure of the Ge10H16 cluster, as provided in Table 1. The Mulliken charge suggests the degree of charge transfer between Ge and H atoms, which obviously indicates that the charge density transfer from the Ge atoms to the H atoms. This is due to the electronegativity of H (2.20) which is higher than that of Ge (2.01), and draws the Ge electrons to the lower energy level. Bond population is an accepted method to investigate the bonding properties between a pair of atoms. The results reported in Table 1 show that the bonding characteristics of both Ge-H and Ge-Ge are covalent. The system total energy (Etot) and band gap are calculated to be -1325.26 and 3.67 eV, which are very close to those of the Si10H16 cluster [4]. The energy gap is fundamentally important for the physical and chemical properties of a solid on which most behaviors of material depend, such as intrinsic conductivity, electronic transitions, and optical transitions. One may note that the band gap of the atomic cluster is much larger than the Ge crystal that is about 0.67 eV. This occurs when the size of a solid is reduced to the nanometer or atomic length scale. Energy gap values more than triple the size of crystalline Si have been reported for nanoscale Si particles [17, 18]. Calculations for the small Si quantum dots and Si nanostructures have predicted a considerable opening of the band gap up to an energy of 4 eV [19], in addition, when the size of a solid deceases to an atomic scale, the effects such as structural change, lattice contraction, atomic relaxation, surface reconstruction, or surface passivation will greatly alter its energy gap. For example, calculation of the Ge clusters with different numbers of atoms give band gap values of 1.35 eV for Ge10, 1.84 eV for Ge9, and 2.64 eV for Ge8 [20]. In our calculations, due to the surface passivation of H, the energy gap is much wider than 2.64 eV, which indicates that the observed photoluminescence radiation is not only due to the size dependent quantum confinement, but also to the surface state transitions.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1.Atomic structure of the Ge10H16 cluster, Ge and H atoms are represented with green and white balls, respectively. | |

|

|

Table 1 Mulliken charge, bond population, total energies (Etot) and band gap of the Ge10H16 cluster. |

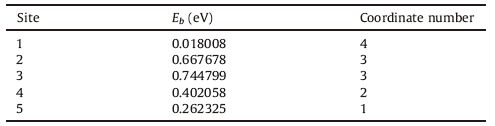

We then studied all the Td positions (labeled with 1-5) for the locations of the Li atom as indicated in Fig. 2. The binding energy (Eb) is defined as,

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2.Five different Td sites for the Li atom (labeled as 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5) in the Ge10H16 cluster. The left is a cross view and right is side view of Fig. 1. The Ge, H, and Li atoms are indicated with green, white, and purple balls, respectively. | |

|

|

Table 2 The record of the calculated binding energies (Eb) and corresponding coordinate number when the Li atom locates at the five various Td sites in Fig. 2. |

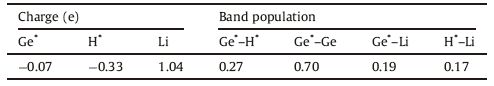

In order to investigate the influence of Li alloying on the geometric structure of Ge10H16 cluster, we choose the most favorable alloying position (site 3) for the location of the Li atom, and then studied the bond lengths, bonding angles, and their Mulliken populations. The results are listed in Tables 3 and 4, where Ge* and H* are the closest Ge and H atoms to the alloyed Li atom. Both the Ge*-H* (1.745 Å) and Ge*-Ge bonds (2.496 Å) increase in length in comparison with the pristine cluster. The increases in the bonding lengths result from the movement of the Ge* atom against the alloyed Li atom, which also causes the ∠Ge- Ge*-Ge bond angle to shrink from 109.3808 to 93.6648 referring to the Ge10H16 cluster. These structural changes provide an explanation of how the system relaxes the strain owing to the Li alloying. Moreover, both the Ge*-Li and H*-Li bond lengths are a little bit shorter than the summation of the radii of Ge, H, and Li atoms, which suggests that the alloyed Li atom has strong chemical interactions with the Ge* and Li* atoms. Upon comparing Table 4 with Table 1, the Mulliken charge of Ge* atom becomes negative and the charge value of its bonded H atom also decreases negatively, while the charge number for Li is 1.04. This information indicates that the valence band of the Li atom is almost transferred to the most neighboring Ge and H atoms. The charge transfer thus weakens the charge density between the Ge*-H* bond from 0.78 to 0.27. However, due to the presence of the Li atom, the band population of Ge*-Ge increases from 0.62 to 0.70. The intensifying of the charge value implies the covalent properties become stronger. The band populations of Ge*-Li and H*-Li are close to zero and the charge number of Li is close to one, which indicates that both the Ge*-Li and H*-Li bonds are ionic nature. This will be further confirmed in the charge density difference plot.

|

|

Table 3 Calculated values of the Ge*-H*, Ge*-Ge, Ge*-Li, and H*-Li bond lengths and the Ge- Ge*-Ge bonding angle when Li atom is located at the site 3. Ge* and H* are defined as the closest Ge and H atoms to the alloyed Li atom. |

|

|

Table 4 Atomic populations of the Ge*, H*, and Li atoms and bond population analyzes between Ge* and H*, Ge* and Ge, Ge* and Li, and H* and Li. |

To elucidate the change of bonding properties between the Ge* and H* atoms, we plotted the charge density difference before and after Li alloying with the cluster, which is shown in Fig. 3. The charge density difference is expressed as following,

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3.The charge density difference before and after Li alloying at site 3 on the (1 1 0) plane. | |

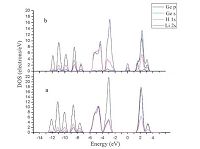

Fig. 4 exhibits the total density of state (TDOS) of the Li-alloyed cluster. Comparing with that of the pristine cluster, there appears two new peaks labeled with A and B. It is clear that peak A corresponds to the Li 1s states. However, peak B is located at the Fermi level, which greatly alters the electronic structure of the Ge10H16 cluster. In order to clarify the electronic interactions between the Li and the neighbor Ge andHatoms, we performed the partial DOS (PDOS) calculation both for the Li-alloyed and pristine Ge10H16 clusters, as shown in Fig. 5 with an energy range from -14 eV to 4 eV. In Fig. 5a, we can see that all the Ge 4s and 4p and H 1s orbitals overlay each other, indicating strong s-p interactions in the Ge and H valence electron states. Comparing Fig. 5a with Fig. 5b, the most noticeable distinctions are the appearance of a peak at the Fermi level, which is derived from Ge 4p, H 1s, and Li 2s states with a majority of Ge 4p and H 1s orbitals. The Li 2s states almost locate at/above the Fermi level, and have intense hybridization with the Ge 4p and H 1s. This finding is consistent with the bond population results, which indicates the alloyed Li has a large amount of electron transfer to H and Ge atoms. The appearance of the peak B alters the semiconducting nature of the Ge10H16 cluster into a conducting property, this may somehow explain why Ge has a very high Li-ion diffusivity.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4.The total density of state (TDOS) of and Li-inserted Ge10H16 cluster at site 3. The energy scale is relative to the Fermi level. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5.The partial density of states (PDOS) of the closest Ge and H atoms in (a) the isolated Ge10H16 and (b) in the Li-alloyed cluster. The energy scale is relative to the Fermi level. | |

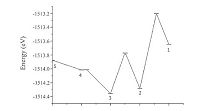

Finally, we calculated the diffusion barriers from the site 5 to site 1 using the complete LST/QST method, which is showed in Fig. 6. One should observe that there exists an energy barrier when Li diffuses from site 3 to site 2 and site 2 to site 1, respectively. Along the pathway from the site 5 to site 4 and site 4 to site 3, no obvious barrier is detected due to the low number of coordinating atoms. As the coordination number increases, the diffusion barrier becomes larger, which is 0.00276 eV from site 4 to site 3; 0.585 eV from site 3 to site 2; and 1.079 eV from site 2 to site 1. The coordination number is considered as a main factor for the Li diffusion, because with a low coordination number, larger lattice space is available for Li to diffuse. It is interesting to see that the relative energy at site 1 is much higher than that at site 2, and the diffusion barrier from site 1 to site 2 (0.169 eV) is largely smaller than that from site 2 to site 1. This indicates that the diffusion from the site 2 to site 1 is difficult to occur, but the inverse process (from site 1 to site 2) is rather likely to happen.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6.The diffusion barriers along the pathways from the site 5 to site 1. | |

The influence of the alloying of Li on the crystal and electronic structures of the Ge10H16 atomic cluster has been investigated. The results of calculations show that the binding energy of Li with the Ge10H16 cluster is greatly impacted by its coordination Ge number. After Li alloying, most valence electrons of the Li atom are transferred to the closest Ge and H atoms, which results in the weakening of the Ge-H bonding. Moreover, Li alloying will push the closest Ge atom away and leads to the decrease of the ∠Ge- Ge-Ge angle. In particular, Li alloying greatly alters the electronic properties of Ge10H16 cluster from semiconducting to conducting coincident with a peak appearing in DOS at the Fermi level. This may account for the reason why Ge has a rather high Li-ion diffusivity.

AcknowledgmentsThe project is financially supported by the Projects of Undergraduate Innovation & entrepreneurship Training Plans of Quanzhou Normal University (No. 201310399008). Wu would like to thank Quanzhou "Tong-Jiang Scholar" program, Fujian "Min- Jiang Scholar" program, program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (No. NCET-13-0879), the Education and Scientific Research Foundation (Class A) for Young Teachers of Education Bureau of Fujian Province, China (No. JA13263).

| [1] | G. Schull, T. Frederiksen, A. Arnau, et al., Atomic-scale engineering of electrodes for single-molecule contacts, Nat. Nanotechnol. 6(2011) 23-27. |

| [2] | J.D. Meindl, Q. Chen, J.A. Davis, Limits on silicon nanoelectronics for terascale integration, Science 293(2001) 2044-2049. |

| [3] | J. Dong, H. Li, L. Li, Multi-functional nano-electronics constructed using boron phosphide and silicon carbide nanoribbons, NPG Asia Mater. 5(2013) e56. |

| [4] | Y.L. Sun, H.L. Song, Y. Yang, et al., First-principles study of lithium insertion into Si10H16 cluster, Comput. Theor. Chem. 1056(2015) 56-60. |

| [5] | C.C. Arnold, D.M. Neumark, Study of Si4 and Si4- using threshold photodetachment (ZEKE) spectroscopy, J. Chem. Phys. 99(1993) 3353-3362. |

| [6] | C.S. Xu, T.R. Taylor, G.R. Burton, et al., Photoelectron spectroscopy of SinH-(n=2-4) anions, J. Chem. Phys. 108(1998) 7645-7652. |

| [7] | C. Sporea, F. Rabilloud, X. Cosson, et al., Theoretical study of mixed silicon-lithium clusters SinLip(+) (n=1-6, p=1-2), J. Phys. Chem. A 110(2006) 6032-6038. |

| [8] | K.D. Rinnen, M.L. Mandich, Spectroscopy of neutral silicon cluster Si18-Si41:spectra are remarkably size independent, Phys. Rev. Lett. 69(1992) 1823-1826. |

| [9] | J.M. Hunter, J.L. Fye, M.F. Jarrold, et al., Structural transition in size-delected germanium cluster ions, Phys. Rev. Lett. 73(1994) 2063-2066. |

| [10] | R. Pillarisetty, Academic and industry research progress in germanium nanodevices, Nature 479(2011) 324-328. |

| [11] | J.G. Ren, Q.H. Wu, H. Tang, et al., Germanium-graphene composite anode for high-energy lithium batteries with long cycle life, J. Mater. Chem. A 1(2013) 1821-1826. |

| [12] | L.C. Yang, Q.S. Gao, L. Li, et al., Mesoporous germanium as anode material of high capacity and good cycling prepared by a mechanochemical reaction, Electrochem. Commun. 12(2010) 418-421. |

| [13] | C. Wang, J. Ju, Y. Yang, et al., (Ⅰ)n situ grown graphene-encapsulated germanium nanowires for superior lithium-ion storage properties, J. Mater. Chem. A 1(2013) 8897-8902. |

| [14] | C. Zhong, J.-Z. Wang, X.W. Gao, et al., (Ⅰ)n situ one-step synthesis of a 3D nanostructrured germanium-graphene composite and its application in lithium-ion batteries, J. Mater. Chem. A 1(2013) 10798-10804. |

| [15] | J.P. Perdew, J.A. Chevary, S.H. Vosko, et al., Atoms, molecules, solid and surface:applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation, Phys. Rev. B:Condens. Matter 15(1992) 6671-6687. |

| [16] | G. Dalba, P. Fornasini, R. Grisenti, et al., Local order in hydrogenated amorphous germanium thin films studied by extended X-ray absorption fine-structure spectroscopy, J. Phys.:Condens. Matter 9(1997) 5875-5888. |

| [17] | T. van Buuren, T. Tiedje, J.R. Dahn, et al., Photoelectron spectroscopy measurements of the band gap in porous silicon, Appl. Phys. Lett. 63(1993) 2911-2923. |

| [18] | M. Ben-Chorin, B. Averboulch, D. Kovalev, et al., (Ⅰ)nfluence of quantum confinement on the critical points of the band structure of Si, Phys. Rev. Lett. 77(1996) 763-766. |

| [19] | C.-Y. Yeh, S.B. Zhang, A. Zunger, Confinement, surface, and chemisorption effects on the optical properties of Si quantum wires, Phys. Rev. B:Condens. Matter 50(1994) 14405-14415. |

| [20] | S. Oeguet, J.R. Chelikowsky, S.G. Louie, Quantum confinement and optical gaps in Si nanocrystals, Phys. Rev. Lett. 79(1997) 1770-1773. |

2016, Vol.27

2016, Vol.27