2. 第四军医大学, 西安 710032;

3. 奥克胜美(北京)生物科技有限公司, 北京 100085

2. The Fourth Military Medical University, Xi'an 710032, China;

3. OnkoRx Ltd., Beijing 100085, China

肿瘤是一种多基因参与,多步骤发展的全身性、系统性疾病,基因组稳定性丧失是肿瘤细胞的一个基本特征,其异常生物学行为主要表现为无限复制、血管生成、侵袭与转移、免疫逃逸等。目前肿瘤所致人口死亡数约占我国人口死亡总数的23%,且发病率不断攀升,已成为危害人民生命健康的首要疾病[1-2]。

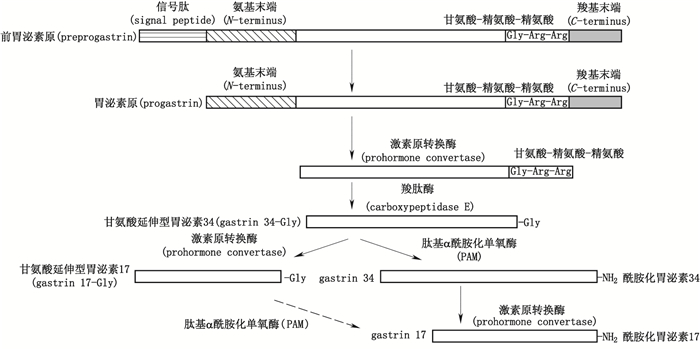

胃泌素为一类胃肠道激素(包括酰胺化胃泌素34、甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素34、酰胺化胃泌素17、甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素17、胃泌素原,见图 1),通过结合相应受体发挥促进胃酸分泌与胃肠道粘膜生长作用;胃泌素过量表达与种类失衡情况下,过量表达的胃泌素17与胃泌素原可通过自分泌、旁分泌或内分泌方式导致多种消化系肿瘤(包括胃癌[4-6]、肠癌[7-9]、胰腺癌[10-11]、食管癌[12]等)的发生发展。如结直肠肿瘤中,Ciccotosto等[13]发现无论幽门螺旋杆菌阳性还是阴性的结肠肿瘤患者,胃泌素原的检出率为100%,甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素的检出率为44%,酰胺化胃泌素的检出率为69%,患者体内非酰胺化胃泌素含量比例显著增加,酰胺化胃泌素含量比例相对降低;van Solinge等[14]研究发现结直肠癌表达胃泌素原的量显著高于正常结直肠粘膜;Paterson等[7]发现外周血胃泌素浓度升高会增加病人患结直肠癌的风险;其余多项研究表明,非酰胺化胃泌素可加速结直肠癌的发展。胃肿瘤中,Goetze等[15]对20例胃腺癌病人肿瘤中酰胺化胃泌素与胃泌素受体的表达情况进行研究,发现酰胺化胃泌素的表达率为80%,胃泌素受体表达率为100%;Sun等[16]研究发现随胃癌发生,人体内血清胃泌素17浓度会显著升高;Huang等[17]也发现随胃癌进展,胃泌素及其受体的蛋白表达呈递增趋势。然而现有治疗上述肿瘤的化疗方法抑瘤作用特异性低,毒副作用大,疗效差,研发抑瘤作用特异性强,毒副作用小,疗效好的新型药物具有重要临床意义,胃泌素分子也正日益得到研究者的重视并已成为治疗相关肿瘤的靶点。

1 胃泌素的促瘤机制 1.1 胃泌素结合的受体种类胃泌素至少可与4类受体结合发挥作用,其中能与其结合的主要受体为胆囊收缩素受体(cholecystokinin receptors,CCK-R),CCK-R包括3类,即CCK-AR、CCK-BR、CCK-CR。

经典的CCK-R为CCK-AR、CCK-BR,其同属于具有7个跨膜区的G蛋白偶联受体超家族,各自氨基酸序列有50%的差异,能被不同的拮抗剂识别[18]。CCK-AR主要位于胰腺腺泡细胞核胆囊平滑肌细胞,其对硫酸化CCK的亲和力要比硫酸化胃泌素或非硫酸化CCK高500~1 000倍[19]。CCK-BR因最初发现于大脑而得名,主要位于肠嗜铬样细胞,主导胃酸分泌,又称为胃泌素受体(gastrin receptor),其含有与CCK和胃泌素亲和力相同的7个跨膜区域,在不同物种间具有高度同源性,可结合酰胺化胃泌素C末端四肽,不能结合甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素与胃泌素原[20-21]。CCK-CR(也称为78 kD胃泌素结合蛋白)属于脂肪酸β-氧化酶类,为低亲和力受体,对酰胺化胃泌素与甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素有相似的亲和力。

除上述受体外,其他可结合胃泌素的新受体也陆续被研究报道。如甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素受体,该受体分布广泛,主要结合甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素的中心七肽铁离子复合物,能促进细胞生长。Singh等[22]还报道了一个45 kD的胃泌素新结合位点,该位点位于纤维母细胞,对甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素和酰胺化胃泌素具有相同的亲和力,也能促进细胞生长。此外,Kowalski-Chauvel等[23]研究发现甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素可与结肠癌细胞系或粘膜内皮细胞表面的F1-ATPase蛋白结合进而促进细胞增殖。膜联蛋白Ⅱ(annexin Ⅱ,ANX Ⅱ)受体为胃泌素原受体,该受体为33~36 kD单体蛋白,也可结合甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素[24]。

总之,目前不同于CCK-AR、CCK-BR、CCK-CR的新受体已广为接受,有学者认为CCK-BR有多种异构体,所谓新受体只是CCK-BR异构体中的1种。如Hellmich等[3]在人结直肠癌细胞上发现了CCK-BR的1个变异体CCK2i4sv,激活该受体可促进细胞增殖。

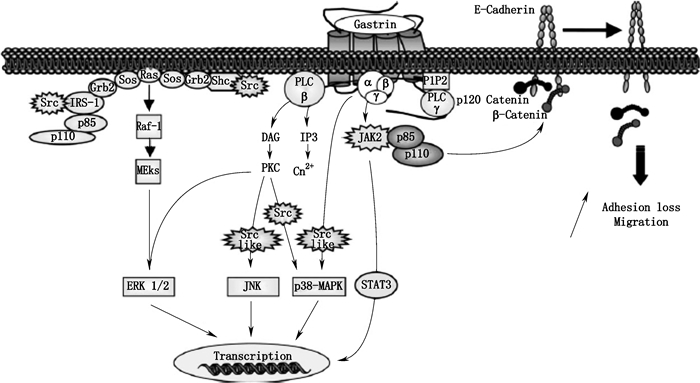

1.2 胃泌素激活的信号通路 1.2.1 酰胺化胃泌素激活的信号通路酰胺化胃泌素激活的信号通路见图 2。

1.2.1.1 ERK 1/2、JNK、p38-MAPK信号通路酰胺化胃泌素可经异源三聚体Gα β γ蛋白激活PLC-β引起磷脂酰肌醇二磷酸(phosphatidyl inositol 4,5-bisphosphate,PIP2)的快速水解,进而生成三磷酸肌醇(inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate,IP3)与甘油二酯(1,2-diacylglycerol,DAG),它们可分别引起Ca2+的调动与蛋白激酶C(protein kinase C,PKC)的活化,活化的PKC可进一步激活ERK 1/2、JNK、p38-MAPK信号通路,其中JNK、p38-MAPK信号通路具有Src激酶依赖性。酰胺化胃泌素也可经Gα β γ直接激活Src依赖的p38-MAPK信号通路[25];还可直接激活Src家族激酶,经Shc/Grb2/Sos或p110/p85/IRS-1Grb2/Sos复合物激活Ras-Raf-1-MEKs依赖的ERK1/2[26]。

小G蛋白超家族包括至少5个亚型(Ras、Rho/Rac/Cdc42、Rab、Arf/Sar1、Ran),该蛋白在许多信号通路中的上游具有关键作用并参与调节多种细胞活动。胃泌素可经CCK-B受体激活ERK1/2与PI3K/AKT通路上游中的小GTPaseRas,进而引发细胞增殖与抗凋亡作用。

1.2.1.2 JAK2-STAT3信号通路酰胺化胃泌素可经Gα β γ直接激活JAK2-STAT3信号通路,其中JAK2激酶还可通过p85/p110复合物引起与细胞膜上E-钙黏蛋白结合的p120连环蛋白、β-连环蛋白脱落,导致细胞粘附力降低产生迁移[27]。此外,酰胺化胃泌素也可经Gβ γ激活PLC-γ1进而形成IP3[3]。

1.2.1.3 经CCK-B受体介导的其他通路除ERK1/2、JNK、p38-MAPK外,在转染CCK-B受体的结肠细胞系RIE-1中胃泌素可激活ERK5通路。该细胞系中,ERK5可能参与转录因子MEF2的激活及CCK-B受体下游环氧化酶-2(cyclooxygenase-2,COX-2)的调节。

某些细胞模型中,如胃与结肠癌细胞、肠上皮细胞、转染CCK-B受体的纤维细胞,胃泌素可增强COX-2的基因表达。该前列腺素合成的关键酶在炎症和致瘤作用中具有重要作用,特别是COX-2可参与过度增殖、变形、侵袭与血管生成。在结肠癌细胞中,ERK1/2与PI3K通路参与胃泌素诱发的COX-2表达,而在肠细胞中,包括ERK1/2、ERK5、JNK、p38-MAPK的多种MAPK通路可导致经胃泌素调节的COX-2转录。

在表达内源性与稳定转染CCK-B受体的不同细胞系中,胃泌素可激活IA型PI3K。其分子机制包括位于酪氨酸残基上衔接r蛋白IRS-1的Src磷酸化,该位点为招募并激活p85/p110 PI3K复合物的结合位点。p85/p110 PI3K下游效应因子AKT(也称为PKB)在CCK-B受体信号通路中也起到作用,并可由胃泌素经磷酸化快速激活。PI3K/AKT通路参与CCK-B受体诱发的细胞增殖及抗凋亡过程,也可调节经该受体诱发的细胞黏附与迁移。

在表达CCK-B受体的胃癌细胞中,胃泌素也可调节与细胞迁移与侵袭(如MMP9,一种基质金属蛋白酶)相关基因的表达,该作用需要PKCs/Raf/ERK1/2通路的参与。

p125-FAK(focal adhesion kinase)为一种位于病灶黏附位点的细胞质蛋白酪氨酸激酶,其可在细胞形态、运动与侵袭中控制多种细胞内信号通路,该蛋白可被包括整合素、RTKs及GPCRs在内的多种细胞膜受体激活。在多种细胞中,p125-FAK磷酸化可导致Src激酶的招募及p125-FAK/Src复合物的活化,该复合物结合并磷酸化整合素相关蛋白(如桩蛋白、踝蛋白)以及衔接蛋白(如Shc、p130Cas)。p125-FAK/Src复合物可经CCK-B受体激活,而经胃泌素形成的p130Cas磷酸化具有Src依赖性。

细胞周期中可控制G1/S过渡的细胞周期素在细胞增殖中具有重要作用,胃泌素可引起周期素D1、D3、E的转录增加。如对表达CCK-B受体的胃癌细胞研究表明胃泌素可介导周期素D1促进子的CRE位点经2个转录因子环磷腺苷效应元件结合蛋白(cAMP-response element binding protein,CREB)与β-链蛋白(β-catenin)的结合进而引起周期素D1生成。

1.2.2 甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素、胃泌素原激活的信号通路甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素、胃泌素原激活的信号通路见图 3。

|

图 3 甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素、胃泌素原激活的信号通路[3] Figure 3 The signal pathway activated by glycine-extend gastrins and progastrin[3] |

甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素可激活PI3K并通过IRS-1/p85/p110复合物引起由可磷酸化核糖体蛋白S6的p70-S6K激酶介导的转录[28];甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素与胃泌素原可直接激活JNK、Src依赖的ERK 1/2与STAT3、JAK2-STAT3信号通路[29]。

1.2.2.2 AKT信号通路甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素与胃泌素原可经Src或JAK2通过p85/p110/PI3K复合物激活AKT(也称为PKB),进而经PI3K/AKT通路激活翻译过程中相关成分(如P70S6K、启动子eIF4E)控制蛋白质合成,调节细胞增殖、抗凋亡、黏附与迁移[29]。此外,胃泌素原还可通过PKCα/p85/p110复合物激活PI3K。

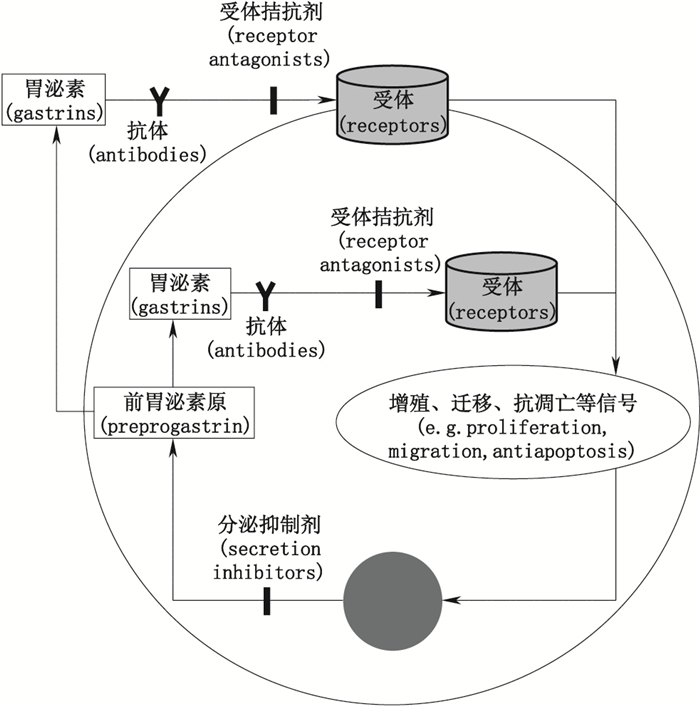

2 分泌抑制法因胃泌素在上述促瘤作用中涉及的信号通路纷繁复杂,且各条信号通路间又存在一定交叉与联系,对单个信号通路阻断难以起到很好疗效。目前抗胃泌素已成为治疗相关肿瘤的有效手段,其具体方法包括分泌抑制、受体拮抗与抗胃泌素抗体法等(见图 4)。

|

图 4 抗胃泌素作用的方法 Figure 4 The methods of anti-gastrins |

胃泌素分泌抑制法主要包括生长抑素(somatostatin)与反义寡核苷酸的应用。生长抑素是胃肠道释放激素的旁分泌抑制剂,其能与三磷酸鸟苷(guanosine triphosphate,GTP)结合蛋白相互作用抑制胃泌素基因的转录进而抑制G细胞释放胃泌素[30]。如奥曲肽(octreotide)、兰瑞肽(lanreotide)、RC160、SMS 201-995为生长抑素类似物,其可通过抑制胃泌素分泌产生抑制胃泌素瘤的作用。研究表明奥曲肽能封闭人结肠癌细胞系HCT116胃泌素基因的转录,减弱胃泌素17对大鼠胰腺癌细胞系AR42J的促生长作用,也能减弱人胃癌细胞系MKN45G的基础增殖[31-32];奥曲肽与兰瑞肽可用于治疗Ⅰ型胃癌[33]及消化系统神经内分泌瘤[34-36];RC160可抑制人胰腺癌细胞系MIA PaCa-2、人结肠癌细胞系HT29的生长,并可显著降低结肠癌细胞的肝转移[37-38];SMS 201-995为人工合成生长抑素类似物,其抑制生长激素分泌的活性比天然生长抑素强3倍,其可通过降低血清胃泌素水平来抑制胃泌素瘤[39]。

有报道称反义寡核苷酸可抑制胃泌素依赖型胰腺癌细胞的体内外增殖,Singh等[40]利用胃泌素反义RNA方法可抑制结肠癌细胞系(Colo312、HCT116)的增殖,但目前对于该方法用于抑制其他相关肿瘤的研究较少,也未见有临床研究报道。胃泌素分泌抑制法的特点为抑瘤作用弱,使用剂量大,易产生毒副作用,作用特异性低。

3 受体拮抗法胃泌素可与多种受体结合发挥作用,其中能与其结合的主要受体为CCK-R。CCK-R拮抗剂主要包括特异性CCK-AR拮抗剂、特异性CCK-BR拮抗剂及非特异性CCK-R拮抗剂,其抗肿瘤作用在体内外实验与临床实验中均已得到证实(见表 1)。

|

|

表 1 CCK-R拮抗剂类型与特点 Table 1 Types and characteristics of CCK-R antagonists |

特异性CCK-AR拮抗剂包括地伐西匹(L-364,718)、氯戊米特、右氯谷胺(CR2017)、MK-329、PNB-028等。如地伐西匹(L-364,718)能抑制LPC1细胞生长也可诱导尤因肿瘤细胞(Ewing tumour cells)死亡[24, 41];氯戊米特为首个非肽类特异性CCK-AR拮抗剂[42];对氯戊米特进行改造修饰后衍生出的右氯谷胺(CR2017)具有较强的抗胃泌素活性[24];MK-329为非肽类CCK-AR拮抗剂,裸鼠体内实验表明其可抑制人胰腺癌的生长[43];PNB-028可抑制免疫缺陷小鼠体内结肠瘤MAC-16、LoVo及胰腺瘤MIA PaCa的生长,并具有较好安全性[44]。

3.2 特异性CCK-BR拮抗剂CCK-BR又称为胃泌素受体(gastrin receptor),可表达于多种肿瘤,曾被认为是介导胃泌素促进肿瘤生长的受体,研究特异性CCK-BR拮抗剂一直受到科研人员的关注,目前已有10余种[如111In-DTPA-CCK8、111In-DTPA-MG0、AG-041R、Z-360、Gastrazole、Netazepide(YF476)、螺谷胺、伊曲谷胺、YM022、CI-988、CR2093、JMV320]被研究报道。

特异性CCK-BR拮抗剂一般为人工合成且与胆囊收缩素/胃泌素(CCK/gastrin)类似的多肽,其C末端一般含有1个能与CCK-BR结合的四肽序列(Trp-Met-Asp-Phe-NH2),如研究表明CCK-8类似物、小胃泌素类似物均可与CCK-BR特异性结合,某些(如111In-DTPA-CCK8、111In-DTPA-MG0)已应用于甲状腺髓样肿瘤病人的临床试验[45]。

L-365,260为首个非肽类CCK-BR拮抗剂,Ohlsson等[46]研究报道L-365,260可抑制外源性胃泌素17促进人胰腺癌细胞系LN 36的体外增殖作用。

Sun等[47]研究报道AG-041R与COX-2抑制剂NS-398联用可协同抑制人胃癌细胞系MKN-45的增殖。Z-360与吉西他滨合用能较好抑制胰腺癌,该联合疗法在欧洲进行用于治疗进行性胰腺癌的Ⅰb/Ⅱa期临床试验[48]。Gastrazole(JB95008)用于治疗进行性胰腺癌已进行临床试验,相对于安慰剂组,其能显著延长生存期,但需长期静脉注射给药,对其应用带来不便[49]。Netazepide在欧洲与美国已注册为治疗胃癌的孤儿药[50],Boyce等[51-52]报道Netazepide可显著减少Ⅰ型胃神经内分泌肿瘤伴自身免疫萎缩性胃炎患者体内肿瘤数量与体积,稳定患者体内胃泌素水平,并具有较好安全性。

伊曲谷胺是选择性最强的氨基酸衍生型CCK-BR拮抗剂,而螺谷胺的效力与特异性均较低[53-54]。YM022与YF476具有较高的特异性[55-58]。氯苯酰色氨酸(benzotript)能抑制多种胃泌素依赖性肿瘤的生长[59]。CI-988可阻断胃泌素结合CCK-BR,其体内外均可抑制结肠癌细胞系的生长[60];Watson等[61]研究报道CI-988可显著延长接种人胃癌腹水瘤MGLVA1asc后SCID鼠的生存期;Dethloff等[62]研究报道CI-988可拮抗酰胺化胃泌素17促进鼠胰腺癌细胞系AR42J的增殖作用;Moody等[63]报道CI-988可抑制CCK-8或胃泌素17所引起人肺癌细胞系NCI-H727内表皮生长因子受体(epidermal growth factor receptor,EGFR)的激活及细胞增殖;Watson等[64]研究报道CR2093可抑制胃泌素17促进裸鼠体内胰腺癌移植瘤AR42J与胃癌移植瘤MKN45的生长作用。

Caplin等[65]研究报道PD135158可显著抑制胰腺癌细胞系AR42J与胚胎肝细胞系WRL68的增殖;Ishizuka等[66]研究报道JMV320可抑制胃泌素17促人胃癌细胞系AGS-P的生长作用。

此外,应用细胞CCK-BR抗原表位制成特异性免疫原,其生成的抗体与CCK-BR具有较高亲和力,可阻断胃泌素与CCK-BR结合而产生抑瘤作用,特别是抗CCK-BR的N末端抗体与CCK-BR结合后能迅速进入细胞发挥作用[67]。如Watson等[68]研究报道应用抗CCK-BR抗血清可反转高胃泌素血症的促肿瘤生长作用。

3.3 非特异性CCK-R拮抗剂丙谷胺是唯一上市的氨基酸型非特异性CCK-R拮抗剂[69-70],其可抑制肿瘤细胞DNA与蛋白合成,抑制肿瘤细胞周期从G0/G1期向S与G2M期过渡[60];能延长大鼠结肠癌MC26荷瘤鼠生存期,也能抑制大鼠胰腺癌细胞AR42J的增殖[69]。Mełeń-Mucha等[71]研究报道丙谷胺与氟尿嘧啶联用可协同抑制鼠结肠癌细胞系Colon 38的体外生长。

CCK-R拮抗剂法的总体特点为抑瘤作用弱,使用剂量大,易产生毒副作用,作用特异性低,不能阻断所有受体,同时也可能阻断其他正常激素(如甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素34、CCK等)的作用,不能阻断某些新发现和未发现的能介导胃泌素促瘤作用的受体作用。

4 抗胃泌素抗体法针对上述抗胃泌素治疗肿瘤方法的特点以及胃泌素在相关肿瘤发生发展中的促瘤作用,近年采用抗胃泌素抗体治疗相关肿瘤的方法成为热点。

4.1 被动免疫法抗胃泌素抗体法包括被动免疫法与主动免疫法,被动免疫法包括抗胃泌素17多抗或单抗的应用。如Hoosein等[72]研究发现抗胃泌素17多克隆抗体可体外抑制人结肠癌细胞系HCT116的基础增殖,外源性胃泌素17可抵消该抑制作用;Zhou等[73]研究报道抗胃泌素单抗可通过中和人胃癌细胞系SGC7901自分泌的胃泌素,阻断胃泌素与CCK-BR结合进而发挥抑制该肿瘤细胞的增殖,降低细胞周期S期的比例,促进细胞凋亡等作用;Caplin等[65]研究报道抗酰胺化胃泌素17与甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素17抗体可抑制酰胺化与甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素17对胰腺癌细胞系AR42J、胚胎肝细胞系WRL68以及甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素17对肝癌细胞系PLC/PRF/5的增殖作用;Blackmore等[69]研究报道应用抗胃泌素抗体可抑制鼠胰腺癌细胞系AR4-2J通过自分泌胃泌素方式促进自身生长的作用;Watson等[61]研究报道抗酰胺化胃泌素17与甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素17抗体可显著延长接种人胃癌腹水瘤MGLVA1asc后SCID鼠的生存期。

被动免疫法需长期注射,费用高,抗体中和作用不具有及时性,且存在异种抗体免疫原性问题。

4.2 主动免疫法主动免疫法为利用胃泌素17、胃泌素原抗原表位所制备疫苗的应用,包括G17-DT交联疫苗、G17-P64K交联或融合疫苗、G17合成多肽疫苗、GAS-TT复合型疫苗,目前国际对此类疫苗的研究方兴未艾,但尚无产品上市。

Tieppo等[74]研究报道抗胃泌素17疫苗可引起胃Ⅰ型良性肿瘤的复原。Rocha-Lima等[75]利用抗胃泌素17疫苗联合伊立替康治疗结直肠癌可延长病人生存期并改善病人生存质量。Gilliam等[76]报道抗胃泌素17疫苗已开展治疗进行性胃肠道恶性癌的Ⅰ/Ⅱ期临床实验、治疗胰腺癌与胃癌的Ⅲ期临床实验,结果表明该疫苗可显著提高进行性胰腺癌病人的存活率;该疫苗联合化疗药的联合用药方法还可提高抑制肿瘤(如胰腺癌、结肠癌、胃癌)的效果,如该疫苗联合吉西他滨的临床实验表明联合疗法较单用吉西他滨能显著提高进行性胰腺癌病人的总生存率。Smith等[77]研究报道抗胃泌素17疫苗在治疗进行性结直肠癌的Ⅰ/Ⅱ期临床实验结果表明该疫苗具有副作用小,中和胃泌素17作用强等特点。Watson等[78]研究报道抗胃泌素17疫苗可抑制鼠结肠肿瘤DHDK12的体内生长,其产生的抗体可特异性中和酰胺化与甘氨酸延伸型胃泌素17。He等[79]研究报道利用胃泌素17、胃泌素原的抗原表位所制备的抗胃泌素疫苗可有效刺激机体产生能同时中和上述2种抗原的特异性抗体,该疫苗抗体联合低剂量化疗药(氟尿嘧啶、顺铂)可显著抑制人胃癌SGC7901肿瘤在裸鼠体内的生长,较传统高剂量化疗药法,联合用药法具有毒副作用小及疗效好的特点。

总体上,主动免疫法接种次数少、可持续产生特异性抗体、抗体中和作用具有及时性、同时可避免因输注异种抗体而产生的免疫原性问题。

5 总结与展望至今以细胞毒性药物为基础的化疗在肿瘤的综合治疗中仍占有重要地位,但疗效与毒性是制约化疗药临床应用的一对矛盾体。虽然两化疗药联合方案较单药可一定程度提高疗效,但联合方案的较大毒副作用仍是制约其临床应用的主要因素,如有研究表明FUP(氟尿嘧啶+顺铂)方案对胃癌的有效率仅为9%~20%,中位生存时间(median survival time,MST)仅有7.2月[80-81]。而一般在两化疗药联合方案基础上再加上第3种细胞毒药物并不能提高疗效,反而可产生更大的毒性反应;目前临床研究均偏向于采用两化疗药联合方案,再加上抑瘤作用特异性强、毒副作用小的靶向药物。有研究者在两化疗药联合方案基础上,结合抗胃泌素抗体靶向治疗药物进行体内抑瘤实验,结果表明该新疗法疗效与标准高剂量化疗药相当,但其毒性显著降低,该特点对于临床提高肿瘤患者生活质量并延长患者的生存时间具有较大应用价值[79]。分子靶向药物具有高靶向性,其毒性的作用谱和临床表现与常用的细胞毒类药物有很大区别;具有调节作用与稳定细胞作用;与常规化疗或放疗联合应用有更好的效果,如分子靶向药物常可与化疗或放疗发挥协同作用,能提高肿瘤对化疗的敏感性;多靶点联合治疗也是未来分子靶向药物应用的发展趋势。而对各类疾病发病机制的基础研究将是决定分子靶向药物开发的决定性因素。相信随着研究者对胃泌素分子各项作用与机制认识的不断扩展与深入,一定会有更多作用特异性强,疗效好,毒性低的新型药物研发成功。

| [1] |

曾益新, 张晓实, 刘强. 分子靶向治疗:肿瘤治疗的里程碑[J]. 癌症, 2008, 27(8): 785. ZENG YX, ZHANG XS, LIU Q. Molecular target therapy:a milestone on the road for curing cancer[J]. Chin J Cancer, 2008, 27(8): 785. |

| [2] |

孙燕. 肿瘤治疗的新里程碑-靶向药物治疗[J]. 肿瘤药学, 2011, 1(1): 1. SUN Y. New milestone in the development of clinical oncology-molecular targeted therapy[J]. Anti Tumor Pharm, 2011, 1(1): 1. |

| [3] |

FERRAND A, WANG TC. Gastrin and cancer:a review[J]. Cancer Lett, 2006, 238(1): 15. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2005.06.025 |

| [4] |

MISHRA P, SENTHIVINAYAGAM S, RANGASAMY V, et al. Mixed lineage kinase-3/JNK1 axis promotes migration of human gastric cancer cells following gastrin stimulation[J]. Mol Endocrinol, 2010, 24(3): 598. DOI:10.1210/me.2009-0387 |

| [5] |

PATEL O, MARSHALL KM, BRAMANTE G, et al. The C-terminal flanking peptide (CTFP) of progastrin inhibits apoptosis via a PI3-kinase-dependent pathway[J]. Regul Pept, 2010, 165(2-3): 224. DOI:10.1016/j.regpep.2010.08.005 |

| [6] |

XU W, CHEN GS, SHAO Y, et al. Gastrin acting on the cholecystokinin2 receptor induce cyclooxygenase-2 expression through JAK2/STAT3/PI3K/Akt pathway in human gastric cancer cells[J]. Cancer Lett, 2013, 332(1): 11. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2012.12.030 |

| [7] |

PATERSON AC, MACRAE FA, PIZZEY C, et al. Circulating gastrin concentrations in patients at increased risk of developing colorectal carcinoma[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2014, 29(3): 480. DOI:10.1111/jgh.12417 |

| [8] |

WESTWOOD DA, PATEL O, BALDWIN GS. Gastrin mediates resistance to hypoxia-induced cell death in xenografts of the human colorectal cancer cell line LoVo[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2014, 1843(11): 2471. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.06.016 |

| [9] |

MASIA-BALAGUE M, IZQUIERDO I, GARRIDO G, et al. Gastrin-stimulated Gα13 activation of Rgnef protein (ArhGEF28) in DLD-1 colon carcinoma cells[J]. J Biol Chem, 2015, 290(24): 15197. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M114.628164 |

| [10] |

HARRIS JC, GILLIAM AD, MCKENZIE AJ, et al. The biological and therapeutic importance of gastrin gene expression in pancreatic a denocarcinomas[J]. Cancer Res, 2004, 64(16): 5624. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0106 |

| [11] |

CAYROL C, BERTRAND C, KOWALSKI-CHAUVEL A, et al. αv integrin:a new gastrin target in human pancreatic cancer cells[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2011, 17(40): 4488. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v17.i40.4488 |

| [12] |

BEALES IL, OGUNWOBI OO. Glycine-extended gastrin inhibits apoptosis in Barrett's oesophageal and oesophageal adenocarcinoma cells through JAK2/STAT3 activation[J]. J Mol Endocrinol, 2009, 42(4): 305. |

| [13] |

CICCOTOSTO GD, MCLEISH A, HARDY KJ, et al. Expression, processing, and secretion of gastrin in patients with colorectal carcinoma[J]. Gastroenterology, 1995, 109(4): 1142. DOI:10.1016/0016-5085(95)90572-3 |

| [14] |

van SOLINGE WW, NIELSEN FC, FRIIS-HANSEN L, et al. Expression but incomplete maturation of progastrin in colorectal carcinoma[J]. Gastroenterology, 1993, 104(4): 1099. DOI:10.1016/0016-5085(93)90279-L |

| [15] |

GOETZE JP, EILAND S, SVENDSEN LB, et al. Characterization of gastrins and their receptor in solid human gastric adenocarcinomas[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2013, 48(6): 688. DOI:10.3109/00365521.2013.783101 |

| [16] |

SUN L, TU H, LIU J, et al. A comprehensive evaluation of fasting serum gastrin-17 as a predictor of diseased stomach in Chinese population[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2014, 49(10): 1164. DOI:10.3109/00365521.2014.950693 |

| [17] |

HUANG GJ, ZHANG YL, LE ZQ, et al. The characteristics of gastrin receptor expression in gastric cancer[J]. Chin Ger J Clin Oncol, 2003, 2(3): 145. DOI:10.1007/BF02842286 |

| [18] |

RAI R, CHANDRA V, TEWARI M, et al. Cholecystokinin and gastrin receptors targeting in gastrointestinal cancer[J]. Surg Oncol, 2012, 21(4): 281. DOI:10.1016/j.suronc.2012.06.004 |

| [19] |

BUNDGAARD JR, REHFELD JF. Posttranslational processing of progastrin[J]. Results Probl Cell Differ, 2010, 50: 207. |

| [20] |

CHUECA E, LANAS A, PIAZUELO E. Role of gastrin-peptides in Barrett's and colorectal carcinogenesis[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2012, 18(45): 6560. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v18.i45.6560 |

| [21] |

SINGH P, SARKAR S, KANTARA C, et al. Progastrin peptides increase the risk of developing colonic tumors:impact on colonic stem cells[J]. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep, 2012, 8(4): 277. DOI:10.1007/s11888-012-0144-3 |

| [22] |

SINGH P, OWLIA A, ESPEIJO R, et al. Novel gastrin receptors mediate mitogenic effects of gastrin and processing intermediates of gastrin on Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts.Absence of detectable cholecystokinin (CCK)-A and CCK-B receptors[J]. J Biol Chem, 1995, 270(15): 8429. DOI:10.1074/jbc.270.15.8429 |

| [23] |

KOWALSKI-CHAUVEL A, NAJIB S, BERTRANDA C, et al. Cell surface F1-ATPase binds the gastrin precursor, G-gly, and mediates its proliferative effects on colorectal cancer cells and vascular endothelial cells[J]. Regul Pept, 2010, 164(1): 48. |

| [24] |

DUFRESNE M, SEVA A, FOURMY D. Cholecystokinin and gastrin receptors[J]. Physiol Rev, 2006, 86(3): 805. DOI:10.1152/physrev.00014.2005 |

| [25] |

TRIPATHI S, FLOBAK A, CHAWLA K, et al. The gastrin and cholecystokinin receptors mediated signaling network:a scaffold for data analysis and new hypotheses on regulatory mechanisms[J]. BMC Syst Biol, 2015, 9: 40. DOI:10.1186/s12918-015-0181-z |

| [26] |

ROZENGURT E, WALSH JH. Gastrin, CCK, signaling, and cancer[J]. Annu Rev Physiol, 2001, 63(1): 49. DOI:10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.49 |

| [27] |

CAO J, YU JP, LIU CH, et al. Effects of gastrin 17 on β-catenin/Tcf-4 pathway in Colo320WT colon cancer cells[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2006, 12(46): 7482. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v12.i46.7482 |

| [28] |

KOWALSKI-CHAUVEL A, PRADAYROL L, VAYSSE N, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 and activation of the PI-3-kinase pathway by glycine-extended gastrin precursors[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1997, 236(3): 687. DOI:10.1006/bbrc.1997.6975 |

| [29] |

HOLLANDE F, CHOQUET A, BLANC EM, et al. Involvement of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinases in glycine-extended gastrin-induced dissociation and migration of gastric epithelial cells[J]. J Biol Chem, 2001, 276(44): 40402. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M105090200 |

| [30] |

EVERS BM, PAREKH D, TOWNSEND CM JR, et al. Somatostatin and analogues in the treatment of cancer.A review[J]. Ann Surg, 1991, 213(3): 190. DOI:10.1097/00000658-199103000-00002 |

| [31] |

BAUER W, BRINER U, DOEPFNER W, et al. SMS 201-995:a very potent and selective octapeptide analogue of somatostatin with prolonged action[J]. Life Sci, 1982, 31(11): 1133. DOI:10.1016/0024-3205(82)90087-X |

| [32] |

WATSON SA, MORRIS DL, DURRANT LG, et al. Inhibition of gastrin-stimulated growth of gastrointestinal tumour cells by octreotide and the gastrin/cholecystokinin receptor antagonists, proglumide and lorglumide[J]. Eur J Cancer, 1992, 28A(8-9): 1462. |

| [33] |

MASSIRONI S, ZILLI A, FANETTI I, et al. Intermittent treatment of recurrent type-1 gastric carcinoids with somatostatin analogues in patients with chronic autoimmune atrophic gastritis[J]. Dig Liver Dis, 2015, 47(11): 978. DOI:10.1016/j.dld.2015.07.155 |

| [34] |

POKURI VK, FONG MK, IYER R. Octreotide and lanreotide in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors[J]. Curr Oncol Rep, 2016, 18(1): 7. DOI:10.1007/s11912-015-0492-7 |

| [35] |

SUNDARESAN S, KANG AJ, HAYES MM, et al. Deletion of Men1 and somatostatin induces hypergastrinemia and gastric carcinoids[J]. Gut, 2017, 66(6): 1012. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310928 |

| [36] |

CIVES M, STROSBERG J. The expanding role of somatostatin analogs in gastroenteropancreatic and lung neuroendocrine tumors[J]. Drugs, 2015, 75(8): 847. DOI:10.1007/s40265-015-0397-7 |

| [37] |

QIN Y, SCHALLY AV, WILLEMS G. Treatment of liver metastases of human colon cancers in nude mice with somatostatin analogue RC-160[J]. Int J Cancer, 1992, 52(5): 791. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0215 |

| [38] |

PINSKI J, SCHALLY AV, HALMOS G, et al. Effects of somatostatin analogue RC-160 and bombesin/gastrin-releasing peptide antagonists on the growth of human small-cell and non-small-cell lung carcinomas in nude mice[J]. Br J Cancer, 1994, 70(5): 886. DOI:10.1038/bjc.1994.415 |

| [39] |

SCHALLY AV. Oncological applications of somatostatin analogues[J]. Cancer Res, 1989, 49(6): 6977. |

| [40] |

SINGH P, OWLIA A, VARRO A, et al. Gastrin gene expression is required for the proliferation and tumorigenicity of human colon cancer cells[J]. Cancer Res, 1996, 56(18): 4111. |

| [41] |

MEYER T, CAPLIN ME, PALMER DH, et al. A phase Ⅰb/Ⅱa trial to evaluate the CCK2 receptor antagonist Z-360 in combination with gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2010, 46(3): 526. DOI:10.1016/j.ejca.2009.11.004 |

| [42] |

van der BENT A, BLOMMAERT AG, MELMAN CT, et al. Hybrid cholecystokinin-A antagonists based on molecular modeling of lorglumide and L-364, 718[J]. J Med Chem, 1992, 35(6): 1042. DOI:10.1021/jm00084a009 |

| [43] |

RAI R, CHANDRA V, TEWARI M, et al. Cholecystokinin and gastrin receptors targeting in gastrointestinal cancer[J]. Surg Oncol, 2012, 21(4): 281. DOI:10.1016/j.suronc.2012.06.004 |

| [44] |

PONNUSAMY S, LATTMANN E, LATTMANN P, et al. Novel, isoform-selective, cholecystokinin A receptor antagonist inhibits colon and pancreatic cancers in preclinical models through novel mechanism of action[J]. Oncol Rep, 2016, 35(4): 2097. DOI:10.3892/or.2016.4588 |

| [45] |

ROOSENBURG S, LAVERMAN P, DELFT FL, et al. Radiolabeled CCK/gastrin peptides for imaging and therapy of CCK2 receptor-expressing tumors[J]. Amino Acids, 2011, 41(5): 1049. DOI:10.1007/s00726-010-0501-y |

| [46] |

OHLSSON B, FREDANG N, AXELSON J. The effect of bombesin, cholecystokinin, gastrin, and their antagonists on proliferation of pancreatic cancer cell lines[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol, 1999, 34(12): 1224. DOI:10.1080/003655299750024742 |

| [47] |

SUN WH, ZHU F, CHEN GS, et al. Blockade of cholecystokinin-2 receptor and cyclooxygenase-2 synergistically induces cell apoptosis, and inhibits the proliferation of human gastric cancer cells in vitro[J]. Cancer Lett, 2008, 263(2): 302. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2008.01.012 |

| [48] |

MEYER T, CAPLIN ME, PALMER DH, et al. A phase Ⅰb/Ⅱa trial to evaluate the CCK2 receptor antagonist Z-360 in combination with gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2010, 46(3): 526. DOI:10.1016/j.ejca.2009.11.004 |

| [49] |

MORTON M, PRENDERGAST C, BARRETT TD. Targeting gastrin for the treatment of gastric acid related disorders and pancreatic cancer[J]. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 2011, 32(4): 201. DOI:10.1016/j.tips.2011.02.003 |

| [50] |

BOYCE M, THOMSEN L. Gastric neuroendocrine tumors:prevalence in Europe, USA, and Japan, and rationale for treatment with a gastrin/CCK2 receptor antagonist[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2015, 50(5): 550. DOI:10.3109/00365521.2015.1009941 |

| [51] |

BOYCE M, LLOYD KA, PRITCHARD DM. Potential clinical indications for a CCK2 receptor antagonist[J]. Curr Opin Pharmacol, 2016, 31: 68. DOI:10.1016/j.coph.2016.09.002 |

| [52] |

BOYCE M, MOORE AR, SAGATUN L, et al. Netazepide, a gastrin/cholecystokinin-2 receptor antagonist, can eradicate gastric neuroendocrine tumours in patients with autoimmune chronic atrophic gastritis[J]. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2017, 83(3): 466. DOI:10.1111/bcp.13146 |

| [53] |

REVEL L, FERRARI F, MAKOVEC F, et al. Characterization of antigastrin activity in vivo of CR 2194, a new R-4-benzamido-5-oxo-pentanoic acid derivative[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 1992, 216(2): 217. DOI:10.1016/0014-2999(92)90363-9 |

| [54] |

MAKOVEC F, REVEL L, LETARI O, et al. Characterization of antisecretory and antiulcer activity of CR 2945, a new potent and selective gastrin/CCK(B) receptor antagonist[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 1999, 369(1): 81. DOI:10.1016/S0014-2999(99)00069-2 |

| [55] |

SAGATUN L, MJONES P, JIANU CS, et al. The gastrin receptor antagonist netazepide(YF476) in patients with type 1 gastric enterochromaffin-like cell neuroendocrine tumours:review of long-term treatment[J]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2016, 28(11): 1345. DOI:10.1097/MEG.0000000000000713 |

| [56] |

SATOH M, KONDOH Y, OKAMOTO Y, et al. New 1, 4-benzodiazepin-2-one derivatives as gastrin/cholecystokinin-B antagonists[J]. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo), 1995, 43(12): 2159. DOI:10.1248/cpb.43.2159 |

| [57] |

TAKINAMI Y, YUKI H, NISHIDA A, et al. YF476 is a new potent and selective gastrin/cholecystokinin-B receptor antagonist in vitro and in vivo[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 1997, 11(1): 113. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.110281000.x |

| [58] |

WEBB DL, RUDHOLM-FELDREICH T, GILLBERG L, et al. The type 2 CCK/gastrin receptor antagonist YF476 acutely prevents NSAID-induced gastric ulceration while increasing iNOS expression[J]. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol, 2013, 386(1): 41. DOI:10.1007/s00210-012-0812-5 |

| [59] |

HAHNE WF, JENSEN RT, LEMP GF, et al. Proglumide and benzotript:members of a different class of cholecystokinin receptor antagonists[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1981, 78(10): 6304. DOI:10.1073/pnas.78.10.6304 |

| [60] |

RAI R, CHANDRA V, TEWARI M, et al. Cholecystokinin and gastrin receptors targeting in gastrointestinal cancer[J]. Surg Oncol, 2012, 21(4): 281. DOI:10.1016/j.suronc.2012.06.004 |

| [61] |

WATSON SA, MICHAELI D, GRIMES S, et al. A comparison of an anti-gastrin antibody and cytotoxic drugs in the therapy of human gastric ascites in SCID mice[J]. Int J Cancer, 1999, 81(2): 248. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0215 |

| [62] |

DETHLOFF LA, BARR BM, BESTERVELT LL. Inhibition of gastrin-stimulated cell proliferation by the CCK-B/gastrin receptor ligand CI-988[J]. Food Chem Toxicol, 1999, 37(2-3): 105. DOI:10.1016/S0278-6915(98)00119-7 |

| [63] |

MOODY TW, NUCHE-BERENGUER B, MORENO P, et al. CI-988 inhibits EGFR transactivation and proliferation caused by addition of CCK/gastrin to lung cancer cells[J]. J Mol Neurosci, 2015, 56(3): 663. DOI:10.1007/s12031-015-0533-6 |

| [64] |

WATSON SA, CROSBEE DM, MORRIS DL, et al. Therapeutic effect of the gastrin receptor antagonist, CR2093 on gastrointestinal tumour cell growth[J]. Br J Cancer, 1992, 65(6): 879. DOI:10.1038/bjc.1992.184 |

| [65] |

CAPLIN M, KHAN K, GRIMES S, et al. Effect of gastrin and anti-gastrin antibodies on proliferation of hepatocyte cell lines[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2001, 46(7): 1356. DOI:10.1023/A:1010634031457 |

| [66] |

ISHIZUKA J, MARTINEZ J, TOWNSEND CM, et al. The effect of gastrin on growth of human stomach cancer cells[J]. Ann Surg, 1992, 215(5): 528. DOI:10.1097/00000658-199205000-00016 |

| [67] |

MICHAELI D, CAPLIN M, WATSON SA, et al. Immunogenic compositions to the CCK-B/gastrin receptor and methods for the treatment of tumors: US, 2004/0001842 A1[P]. 2004-01-01

|

| [68] |

WATSON SA, MORRIS TM, MCWILLIAMS DF, et al. Potential role of endocrine gastrin in the colonic adenoma carcinoma sequence[J]. Br J Cancer, 2002, 87(5): 567. DOI:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600509 |

| [69] |

BLACKMORE M, HIRST BH. Autocrine stimulation of growth of AR4-2J rat pancreatic tumour cells by gastrin[J]. Br J Cancer, 1992, 66(1): 32. DOI:10.1038/bjc.1992.212 |

| [70] |

CHAO C, HELLMICH MR. Gastrin, inflammation, and carcinogenesis[J]. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes, 2010, 17(1): 33. DOI:10.1097/MED.0b013e328333faf8 |

| [71] |

MEŁEN-MUCHA G, ŁAWNICKA H, MUCHA S. The combined effects of proglumide and fluorouracil on the growth of murine Colon 38 cancer cells in vitro[J]. Endokrynol Pol, 2005, 56(6): 934. |

| [72] |

HOOSEIN NM, KIENER PA, CURRY RC, et al. Antiproliferative effects of gastrin receptor antagonists and antibodies to gastrin on human colon carcinoma cell lines[J]. Cancer Res, 1988, 48(24 Pt 1): 7179. |

| [73] |

ZHOU JJ, CHEN ML, ZHANG QZ, et al. Blocking gastrin and CCK-B autocrine loop affects cell proliferation and apoptosis in vitro[J]. Mol Cell Biochem, 2010, 343(1-2): 133. DOI:10.1007/s11010-010-0507-5 |

| [74] |

TIEPPO C, BETTERLE C, BASSO D, et al. Gastric type Ⅰ carcinoid:a pilot study with human G17DT immunogen vaccination[J]. Cancer Immunol Immunother, 2011, 60(7): 1057. DOI:10.1007/s00262-011-1031-5 |

| [75] |

ROCHA-LIMA CM, de QUEIROZ MARQUES JUNIOR E, BAYRAKTAR S, et al. A multicenter phase Ⅱ study of G17DT immunogen plus irinotecan in pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer progressing on irinotecan[J]. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 2014, 74(3): 479. DOI:10.1007/s00280-014-2520-y |

| [76] |

GILLIAM AD, WATSON SA. G17DT:an antigastrin immunogen for the treatment of gastrointestinal malignancy[J]. Expert Opin Biol Ther, 2007, 7(3): 397. DOI:10.1517/14712598.7.3.397 |

| [77] |

SMITH AM, JUSTIN T, MICHAELI D, et al. Phase Ⅰ/Ⅱ study of G17-DT, an anti-gastrin immunogen, in advanced colorectal cancer[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2000, 6(12): 4719. |

| [78] |

WATSON SA, MICHAELI D, GRIMES S, et al. Gastrimmune raises antibodies that neutralize amidated and glycine-extended gastrin-17 and inhibit the growth of colon cancer[J]. Cancer Res, 1996, 56(4): 880. |

| [79] |

HE Q, GAO H, GAO M, et al. Anti-gastrins antiserum combined with lowered dosage cytotoxic drugs to inhibit the growth of human gastric cancer SGC7901 cells in nude mice[J]. J Cancer, 2015, 6(5): 448. DOI:10.7150/jca.11400 |

| [80] |

VANHOEFER U, ROUGIER P, WILKE H, et al. Final results of a randomized phase Ⅲ trial of sequential high-dose methotrexate, fluorouracil, and doxorubicin versus etoposide, leucovorin, and fluorouracil versus infusional fluorouracil and cisplatin in advanced gastric cancer:a trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gastrointestinal Tract Cancer Cooperative Group[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2000, 18(14): 2648. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2000.18.14.2648 |

| [81] |

OHTSU A, SHIMADA Y, SHIRAO K, et al. Randomized phase Ⅲ trial of fluorouracil alone versus fluorouracil plus cisplatin versus uracil and tegafur plus mitomycin in patients with unresectable, advanced gastric cancer:The Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study (JCOG9205)[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2003, 21(1): 54. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2003.04.130 |

2018, Vol. 38

2018, Vol. 38