2. 哈尔滨工业大学 机电工程学院,黑龙江 哈尔滨 150001

2. School of Mechatronics Engineering, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150001, China

由于人体运动学信息在教学[1]、医疗[2]、运动康复[3-4]、人体外骨骼[5-7]等领域的广泛应用,人体关节力矩的求解方法一直受到学者的广泛关注。目前对于关节力矩的求解方法根据原理主要分为两种:1)采取人体表面肌电信号(surface ectromyography)结和人体肌肉骨骼模型求解相应的关节力矩[8-9];2)运用惯性测量元件测量人体运动学信息,通过构建人体逆动力学模型来解算关节力矩。在人体逆动力学模型方面,哈尔滨工业大学的郭伟等[10]将单腿支撑相的人体建立为刚体模型,通过光学动捕系统测量人体运动学信息,对人体下肢关节力矩进行解算;韩国科学技术院结合人体上肢质心的运动规律,建立了弹簧单摆模型进而解算了人体踝关节的关节力矩[11]。由于对动力学模型精确度的依赖较高,上述方法难以提供准确度较高的关节力矩求解结果。与之相比,以表面肌电信号作为输入的人体肌肉骨骼模型,由于肌肉相对于关节的高度冗余,具有能够预测肌肉出力、体现拮抗肌肉驱动、反算肌肉激活等方面的优势,能够体现出更丰富的人体运动及肌肉激活的信息。因此近些年来,很多学者提出了使用肌电信号求解关节力矩的方法。该方法主要分为4个过程:1)从肌电信号(sEMG)求解肌肉激活(Muscle activation);2)根据神经肌肉骨骼模型求解肌肉力;3)求解关节力臂;4)参数辨识。现阶段所使用的模型例如Zajac在1989年提出的模型[12]或Huxley的更复杂的生物物理模型[13-14],又如Zahalak的模型[15-16](Zahalak,1986,2000年)是基于Hill的经典著作[17]。本文主要总结了近年来使用肌电信号以及相关生理学模型对关节力矩的求解方法,并阐述了利用神经肌肉骨骼模型对关节力矩求解的基本原理及过程,给出了模型中涉及的一些参数的生理学统计数据。又给出了以求解关节划分的该研究的主要应用,最后总结了这一求解方法目前所存在的问题和之后发展的方向。

1 基本原理人体运动过程中,骨骼肌的收缩是由我们的神经系统进行控制的,当我们的大脑产生的运动指令经过脊柱中枢神经传递到骨骼肌时,骨骼肌开始收缩,与此同时,骨骼肌会产生一定的动作电位,该电位在皮肤表面表现即为肌电信号。

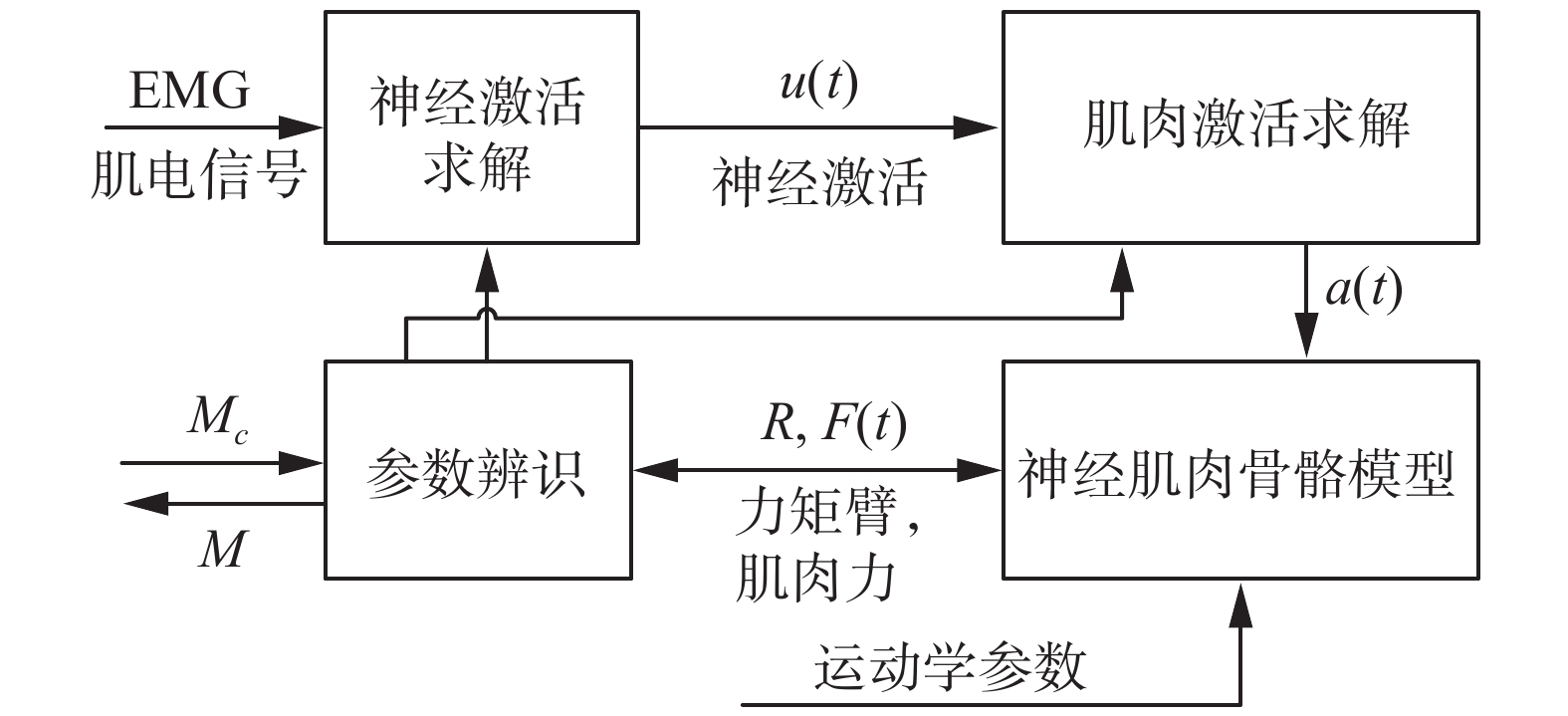

我们将通过表面电极获取的肌电信号进行一定的处理。之后利用神经激活模型求解神经激活u(t)。将u(t)代入到肌肉激活模型来求解肌肉受到神经信号后的肌肉激活程度a(t),将其代入神经肌肉骨骼模型进而来计算肌肉力和关节力矩臂,进一步得到关节力矩M,之后根据实际测量关节力矩Mc,对整体肌肉骨骼模型的参数进行优化,最终得到准确的关节力矩。整个流程如图1所示。

|

Download:

|

| 图 1 关节力矩求解流程 Fig. 1 Joint moment solution | |

从对于肌肉骨骼模型的叙述可知,肌电信号是由神经信号刺激肌肉激活所产生的,因此肌电信号可以用来衡量肌肉激活及神经激活。然而其间的映射关系是高度非线性的,同时肌电信号的幅度也受诸多因素影响[18],(例如放大器的增益、所选用的电极类型、电极相对于肌肉运动点的位置、肌肉与电极之间的组织关系等),所以很难直接利用肌电信号精准的计算和预测肌肉激活以及肌肉力。

为了从肌电信号中获取有效信息以求解关节力矩,必须滤除噪声,量化神经及肌肉的激活程度。为此,在求解肌肉激活和肌肉力之前,先要对肌电信号进行预处理,再将预处理后的肌电信号转化为神经激活u(t)。预处理过程可以描述为:1) 5~30 Hz高通滤波:由于放大器的精度不足或者电极相对肌肉发生串动会导致采集到的肌电信号的平均值产生时变的漂移,而这部分信号并不属于肌电信号,因此要消除这些由于采集误差导致的直流偏移或低频噪声。2)全波整流和归一化(除以最大自主收缩期间获得的峰值整流EMG值)处理[19-20]。3)低通滤波:肌肉的电信号的频率成分超过了100 Hz,但是肌肉力的频率要比这低得多,因此为了使肌电信号和肌肉力量相关,滤除高频成分是非常重要的[12, 18, 21]。4)求解神经激活:求取神经激活u的方法如下:

| $u(t) = \alpha \times e\Bigg(t - \frac{d}{{{T_E}}}\Bigg) - {\beta _1} \times u(t - 1) - {\beta _2} \times u(t - 2)$ | (1) |

式中:u(t)为第t个采样点的神经激活;e为肌电信号;

| ${\beta _1} = {\gamma _1} + {\gamma _2}(\left| {{\gamma _1}} \right| < 1;\left| {{\gamma _2}} \right| < 1)$ | (2) |

| ${\beta _2} = {\gamma _1} \cdot {\gamma _2}\left( {\left| {{\gamma _1}} \right| < 1;\left| {{\gamma _2}} \right| < 1} \right)$ | (3) |

| $\alpha - {\beta _1} - {\beta _2} = 1$ | (4) |

从肌电信号得到神经激活后,便可以对肌肉激活进行计算和估计。其具体过程为

| $\left\{ \begin{array}{l} a(t) = d\ln (cu(t) + 1) ,\;\;\;\;\;0 \leqslant u(t) < 0.3\\ a(t) = mu(t) + b,\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;0.3 \leqslant u(t) < 1 \end{array} \right.$ | (5) |

式中:u(t)是神经激活;a(t)是肌肉激活。肌肉激活系数c、d、m和b可以根据曲线过渡点及导数关系同时求解。一些学者又将进行了一定的化简[8, 22-23]:

| $a(t) = \frac{{{{\rm{e}}^{Au(t) - 1}}}}{{{{\rm{e}}^A} - 1}}$ | (6) |

其中,A(−3,0)是非线性因子。对于肌肉激活的求解还有一些方法主要如表1所示[24]。

| 表 1 肌肉激活方法列举 Tab.1 Muscle activation method |

表1中列举的公式中Manal在文献[23]中提出的方法相对简便,求解的肌肉激活准确性较高,受到广泛的使用。Cavallaro在文献[25]中提出的方法是对Manal方法的简化,其中参数A1是Manal方法中指数常数项的估计,这里会进一步引入误差,因此准确性较Manal方法低,至于Manal在文献[26]中提出的方法是针对于特定肌肉激活求解所提出的方法,该方法进一步提高了计算精度,但是相对比较繁琐,适用广泛性不强。至于Chadwich、Rengifo、Chadwick、Telen提出的方法为常微分方程,求解比其他方法繁琐,使用相对较少。

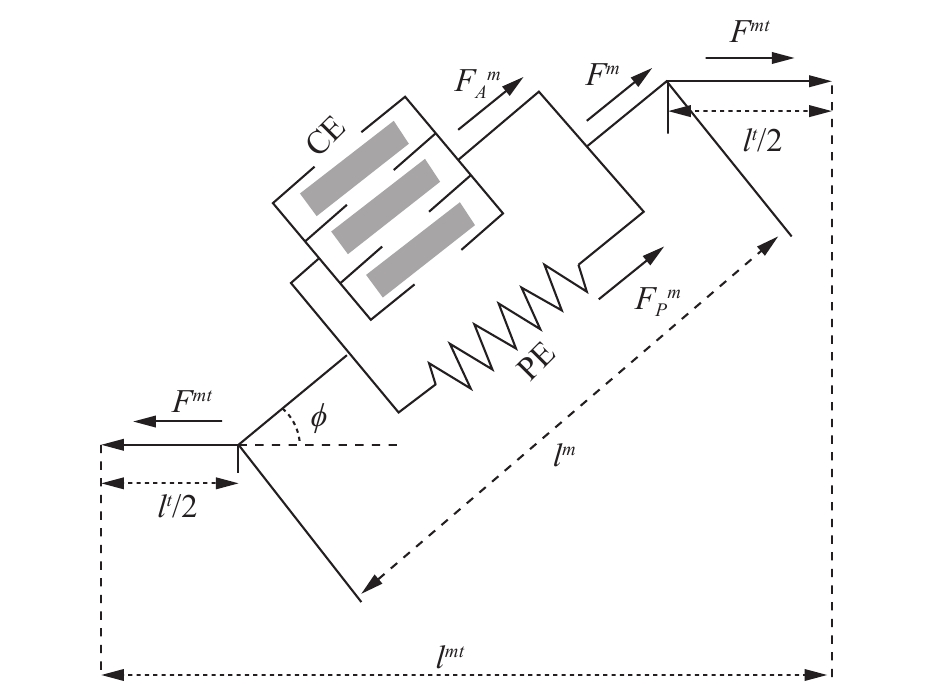

4 神经肌肉骨骼模型在获得肌肉激活及相关人体运动学信息后,便可以利用肌肉骨骼模型对肌肉力以及关节力矩进行求解。肌肉骨骼模型如图2所示,其描述了肌肉肌腱的力的作用关系,其中用一个主动收缩单元CE和一个被动收缩单元PE来近似骨骼肌的工作情况。

|

Download:

|

| 图 2 肌肉骨骼模型 Fig. 2 Musculoskeletal model | |

整个模型对于骨骼肌力量的求解可以由式(7)进行表示:

| $\begin{array}{c} \;\;{F^{mt}}(\theta,t) = {F^t} = [F_A^m + F_P^m]\cos\; \phi= \\ \;[{f_A}(l)f(v)a(t)F_o^m + {f_P}(l)F_o^m]\cos\; \phi \end{array}$ | (7) |

式中:

根据肌肉骨骼模型来看,肌肉力的大小和肌肉纤维长度是有一定关系的,这里将这种关系分别描述为

| $\begin{array}{c} {f_A}(l) = \sin ({b_1} {l^2} + {b_2}l + {b_3})\\ ({b_1} = - 1.317,{b_2} = - 0.403,{b_3} = 2.454) \end{array}$ | (8) |

另外一种求解方式为

| ${f_A}(l) = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{\delta _0} + {\delta _1}l + {\delta _2}{l^2}}&{0.5 \leqslant l \leqslant 1.5}\\ 0&{\text{其他}} \end{array}} \right.$ | (9) |

被动收缩力同肌肉纤维长度之间的关系可以表述为[32, 35]

| $\begin{array}{l} {f_P}(l) = {A_P} \cdot [{{\rm{e}}^{{K_{pe}}\frac{{{l^m} - l_o^m}}{{l_o^m}}}} - 1] \\ {A_P} = 0.129,{K_{pe}} = 4.525 \\ \end{array} $ | (10) |

可以简化为

| ${f_P}(l) = \frac{{{{\rm{e}}^{10(l - 1)}}}}{{{{\rm{e}}^5}}} = {{\rm{e}}^{10l - 15}}$ | (11) |

这里所提到的l即肌肉纤维长度是经过归一化之后的长度,即

| $l_o^m(t) = {l_o}(\lambda (1 - a(t)) + 1)$ | (12) |

式中:

肌肉力量的大小除了和肌肉纤维长度有关系外,它还受到肌肉纤维收缩速度的影响[12, 35-36]。Hill在1938年建立肌肉骨骼模型最初是为了研究肌肉收缩和热量之间的关系[17],Hill通过实验发现,当肌肉缩短一个距离x时,伴随肌肉释放出一个收缩热量(H),因此有

| $H = ax$ | (13) |

式中:a是与肌肉横截面相关的热常数。同时Hill还推测

| $E = {F^m}x + H = ({F^m} + a)x$ | (14) |

等式右边对时间求导得

| $({F^m} + a)\frac{{{\rm{d}}x}}{{{\rm{d}}t}} = ({F^m} + a){v^m}$ | (15) |

式中:

| $({F^m} + a){v^m} = b(F_o^m - {F^m})$ |

整理得

| ${F^m} = \frac{{F_o^mb - a{v^m}}}{{b + {v^m}}}$ | (16) |

到这里肌肉力和肌肉纤维收缩速度的关系是建立在最佳纤维长度的情况下的,没有考虑到纤维长度变化所带来的影响。下面给出变纤维长度的肌肉力和肌肉收缩速度之间的关系:

| ${F^m} = \Bigg(\frac{{F_o^mb - a{v^m}}}{{b + {v^m}}}\Bigg){f_A}(l)$ | (17) |

对于肌肉的舒张时的情况为

| ${F^m} = \Bigg(F_{{\rm{Ecc}}}^mF_o^m - (F_{{\rm{Ecc}}}^m - 1)\dfrac{{F_o^mb' + a'{v^m}}}{{b' - {v^m}}}\Bigg){f_A}(l)$ | (18) |

式中:

| $\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {f(v) = \dfrac{{0.3\Bigg[\dfrac{{{v^m}}}{{v_{\max }^m}} + 1\Bigg]}}{{ - \dfrac{{{v^m}}}{{v_{\max }^m}} + 0.3}}},&{\dfrac{{{v^m}}}{{v_{\max }^m}} < 0}\\ {f(v) = \dfrac{{2.34\dfrac{{{v^m}}}{{v_{\max }^m}} + 0.039}}{{1.3\dfrac{{{v^m}}}{{v_{\max }^m}} + 0.039}}},&{\dfrac{{{v^m}}}{{v_{\max }^m}} \geqslant 0} \end{array}} \right.$ | (19) |

其中

求得肌肉激活之后,便可以利用肌肉激活对肌肉力

| $ {\varepsilon ^t} = \frac{{{l^t} - l_s^t}}{{l_s^t}} $ | (20) |

式中:

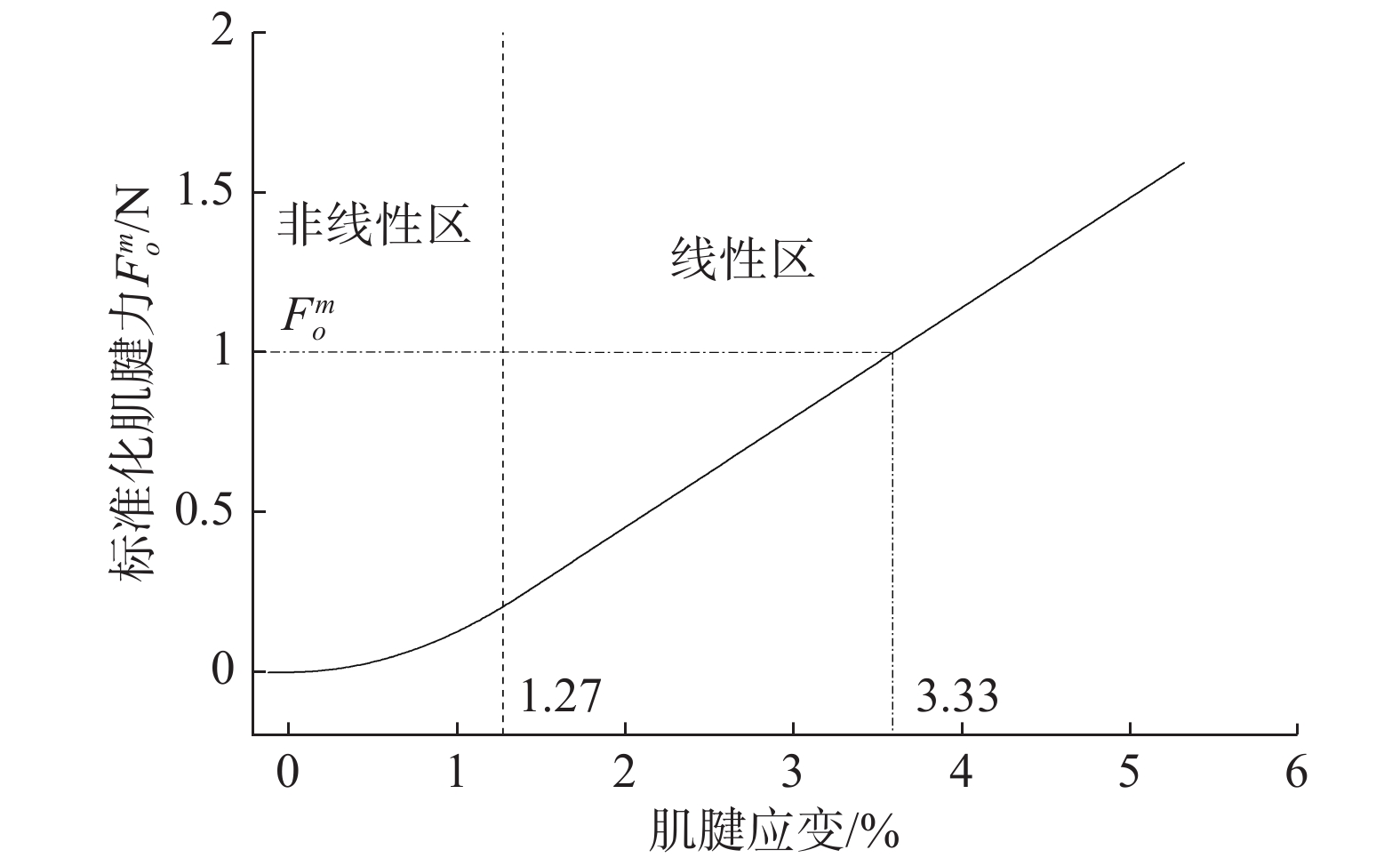

这里值得注意的是,肌腱应变不会为负值,由式(20)可以看到,只有当肌腱束长度大于肌腱束松弛长度时,力才会随应变变化,否则肌腱束力为零。肌腱应变与肌腱力的变化关系由式(21)及图3所示。

| ${F^t} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} 0,\qquad {\varepsilon \leqslant 0}\\ {1\;480.3{\varepsilon ^2}},&{0 < \varepsilon < 0.012\;7}\\ {37.5\varepsilon - 0.237\;5},&{\varepsilon \geqslant 0.012\;7} \end{array}} \right.$ | (21) |

|

Download:

|

| 图 3 肌腱力与应变关系 Fig. 3 Relationship between tendon stress and strain | |

如图2所示,由于肌腱与肌肉纤维串联,肌腱力Ft和肌肉力Fm存在下述关系:

| $ {F^t} = {F^m}\cos \;\phi $ | (22) |

其中,

羽状角的大小随关节的活动及肌肉的收缩而变化。KAWAKAMI Y等[38]在1998年利用超声波发现,内侧腓肠肌羽状角可根据关节角度和肌肉激活量从22°变为67°。虽然有一些简单的模型描述了羽状角随肌肉激活的变化,但很少有人通过体内成像研究(如超声)来证实这些变化。通过对动物肌肉的研究,一些研究人员已经提出了相对比较复杂的模型[39](如Woittiez等)和一些简化的模型[40](Scott&Winter)。为便于计算,利用简化模型来预测收缩肌肉的摆动角度,记采样点为t时的羽状角为

| $\phi (t) = {\sin ^{ - 1}}\Bigg(\frac{{l_o^m\sin {\phi _0}}}{{{l^m}(t)}}\Bigg)$ | (23) |

式中

从上文对于肌肉肌腱力的论述来看,对于肌肉力的求解来说,肌腱长度的大小的求解是至关重要的,其值可以根据式(24)得到:

| ${l^{mt}} = {l^t} + {l^m}\cos \;\phi $ | (24) |

即

| ${l^t} = {l^{mt}} - {l^m}\cos \;\phi $ | (25) |

从式(21)和式(25)可以看出,肌肉肌腱长度对于求解肌腱长度和肌腱力是必不可少的,但是肌肉肌腱长度属于人体生物参数,求解较为困难。Menegaldo等[41]在2004年提出了一种用于计算下肢肌肉肌腱长度和关键力矩臂的方法。其研究参照了Delp等[42-43]提出的生理模型所求出的生理学参数。其具体的计算方法如下:

| $\begin{array}{c} L({Q_1},{Q_2},{Q_3},{Q_4}) = {a_1} + {a_2}{f_1}({Q_1},{Q_2},{Q_3},{Q_4}) +\\ {a_3}{f_2}({Q_1},{Q_2},{Q_3},{Q_4}) + \cdots + {a_n}{f_{n - 1}}({Q_1},{Q_2},{Q_3},{Q_4}) \end{array}$ | (26) |

式中:L表示肌肉肌腱长度;ai表示为待定系数;fi是指泛型非线性系数,根据拟合曲面的形状进行选择。而

| ${l^{mt}} = {b_0} + {b_1} \theta $ | (27) |

式中:b0和b1是待定参数;θ为关节角度,可以使用惯性传感器或光学动捕等方式进行测得。

4.6 肌肉力整合求解通过对整个过程的论述,在这里重新讨论最初给定的式(7),这时式中的大部分未知量已经在上述内容给出了求解方法,然而现在依然不能依靠式(7)直接给出对于肌肉力量的一个估计,因为肌肉纤维长度的大小并不知道。

| $\begin{gathered} {F^{mt}}(\theta ,t) = {F^t} = [F_A^m + F_P^m]\cos \phi = \hfill \\ [{f_A}(l)f(v)a(t)F_o^m + {f_P}(l)F_o^m]\cos \;\phi \hfill \\ \end{gathered} $ |

对于肌肉纤维长度的求解需要用到数值积分的方法,因此这里首先根据上述方程(7)进行对肌肉力−肌肉收缩速度关系进行求解:

| $f(v) = \frac{{{F^t} - f_p^lF_o^m\cos \;\phi }}{{{f_A}(l)a(t)F_o^m\cos \;\phi }}$ | (28) |

在设定一个初始的肌肉纤维长度后,便可根据式(8)~(11)求出肌肉力和肌肉纤维长度的关系;根据式(12)和(23)可以对羽状角进行相应的估计,又可以根据式(28)求出肌肉力−肌肉收缩速度关系,之后根据式(19)得到肌肉纤维速度,这时候利用数值积分的方法可以推出下一采样点的肌肉纤维长度。将该时刻的肌肉纤维长度以及关节角度代入到式(24)和(26)后,可以求得此时的肌腱长度,再利用式(20)和(21)未求出该时刻的Ft,再代入到式(7),进行下一步的计算,不断重复此过程,最终得到测试时间段的肌肉力。

4.7 关节力矩求解| ${M^j}(\theta,t) = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^m {({r_i}(\theta ) \cdot F_i^{mt}(\theta,t))} $ | (29) |

式中:

| $r(\theta ) = \frac{{\partial {l^{mt}}(\theta )}}{{\partial \theta }}$ | (30) |

如上所述,d、γ1、γ2、A是求解肌肉激活的4个主要参数,假设所有参与的肌肉都具有相同的肌肉激活求解过程。因此,只需要调整4个激活参数。在肌肉肌腱力求解过程中,

Ai等[46]进行了两组优化,第1组根据受试者特定的肌肉骨骼几何模型进行估计;第2组采用通用的肌肉骨骼模型。之后将两组原始肌电信号和运动学数据都输入到优化模型(非线性最小二乘和levenberg-marquardt算法)中,使得估计力矩和参考力矩差值最小。Menegaldo等[47]采用式(31)对参数进行优化评价指标:

| ${\rm{RMSE}} = \dfrac{1}{{{\rm{T}}{{\rm{M}}_{{\rm{MAX}}}}}}\sqrt {\frac{{\displaystyle\sum\limits_{t = 1}^N {{{({\rm{TM}}(t) - {\rm{TS}}(t))}^2}} }}{N}} \times 100{{\% }}$ | (31) |

式中:

Li等[49]采用遗传算法对未知生理参数进行优化,优化目标函数为

| $\min \sum\limits_{i = 1}^n {{{({\theta _{ci}} - {\theta _{mi}})}^2}} $ |

式中:θci为实际测量关节角度;θmi为模型预测关节角度,这里其使用正向动力学方法,利用预测的关节力矩进一步地求解运动学信息。遗传算法初始种群在优化过程中进化,其参考了文献[50-51]中的结果,减少了搜索空间,提高了优化速度,并通过模型参数辨识,得到最接近实际关节角的最优模型参数值,再通过实验结果得到均方根误差进而提高精度。Son等[52]采用混合正逆动力学方法对参数进行调整,即假设肌电驱动模型估计的关节力矩近似等于测试得到的关节力矩:

| $\min \sum\limits_{t = 1}^n {\Bigg({M_t} - \sum\limits_{j = 1}^m {{r_{tj}} \cdot {F_{kj}}} \Bigg)} $ |

式中:Mk为采样点k时的测定力矩;rkj为j肌肉在k采样点时刻的力矩臂;Fkj为j肌肉在k采样点时的肌肉力。Buongiorno D等[53]做了关于遗传算法(基于Genocop Ⅲ的有约束和无约束算法[54])和线性优化方法(线性最小二乘)的对比研究工作。

为了能够为之后的相关研究提供一些帮助,这里根据文献[20, 51, 53-61]列出了一些常用肌肉的生理参数,如表2。

| 表 2 肌肉生理参数表 Tab.2 Muscle physiological parameters |

表面肌电信号和肌肉骨骼模型主要应用于医学和运动学等方面,这种方法能够帮助人们更好地理解人体运动和人体在进行运动时力矩信息[62-63]。现阶段基于EMG的神经肌肉骨骼模型已经被用于估计人体多处关节的力矩,神经肌肉骨骼模型的应用如表3所示。

| 表 3 神经肌肉骨骼模型的应用 Tab.3 Application of neuromusculoskeletal model |

随着其他学科的不断发展和人们对于进一步理解人类运动意图的需要,该方法又在一些机械运动控制、外骨骼控制等方面得到了应用[23, 64-66]。同时,在体育运动中对运动员的肌肉力量进行分析[67-68]、康复医学中使用该方法对一些瘫痪患者进行肌肉康复训练[46, 69]、人体假肢依靠肌电信号进行控制,使得假肢能够根据人类意图去辅助患者,以及关节疾病等领域也广泛应用了这种方法[70]。在未来,由于人机合作的需求不断加大,这种分析人体运动内力的方法将会得到更加广泛的应用。

7 结束语肌电信号作为一种可方便获取的人体信号,受到了越来越多学者的关注,利用其对关节力矩进行求解可以充分了解人体运动时肌肉骨骼力学特性。本文结合了大量文献给出了利用肌电信号对关节力矩进行求解的方法和基础模型的综合性论述。目前该方法依然存在着一些问题。

肌电信号方面:1)作为模型的输入信号,肌电信号具有高变异性;2)测得的信号为多肌肉信号融合信号,受噪声干扰严重;3)在利用其求解肌肉激活的过程中,映射关系难以得到正确性的评价;4)目前这种映射关系并没有考虑到运动过程中肌肉疲劳对于肌肉活性的影响;5)肌电信号采集设备相对复杂,对应用环境依赖性较强,难以得到广泛的实际应用。

神经肌肉骨骼模型方面:1)生理参数较多,优化求解过程繁琐,求解过程复杂,难以评价中间变量的求解正确性,误差会随着过程不断积累;2)利用神经肌肉骨骼模型控制相关人机交互设备,难以实现实时控制的目标,且不易解决个体差异性问题;3)模型中神经激活和肌肉激活的时间序列以及时间延迟难以准确估计。

在未来对于使用肌电信号求解关节力矩技术研究时,需关注以下可实现技术突破的研究点。

1)提升肌电信号采集设备准确性和稳定性。肌电信号作为整体的输入信号,其获取精度的提升会在大程度上提高估计的关节力矩的准确性。减少肌电信号融合对于最终结果的影响,提高肌电传感器采集位置的容错性。

2)简化模型计算过程及优化参数,提高整体计算模型的鲁棒性。给出对于确定模型参数最为有利的矫正动作,同时寻找一种能够实现实时计算的方法,对于利用肌电信号求解关节力矩这一方法的实时应用以及减小计算内存和累计误差十分重要。提高模型参数的泛化能力,减少优化过程,进而解决个体差异问题对于人机交互设备的发展具有深远意义。

3)给出单肌肉对于肌肉关节力矩的影响关系,减少测量肌肉数量,可以减少整体模型的参数。同时给出肌肉疲劳对于整个模型的计算结果的影响,可以更加深层次地理解肌电信号同肌肉力之间的关系。

| [1] |

MATHEW A J, NUNDY M, CHANDRASHEKARAN N, et al. Wrestle while you learn: EMG as a teaching tool for undergraduate skeletal muscle physiology teaching[J]. Advances in physiology education, 2019, 43(4): 467-471. DOI:10.1152/advan.00029.2019 ( 0) 0)

|

| [2] |

孙全义, 陈雪丽, 李春梅, 等. 颏下肌群表面肌电信号评定脑卒中患者吞咽障碍的价值[J]. 广西医科大学学报, 2019, 36(7): 1104-1107. SUN Quanyi, CHEN Xueli, LI Cunmei, et al. The value of submental muscle surface electromyography signal for evaluating dysphagia in stroke patients[J]. Journal of Guangxi medical university, 2019, 36(7): 1104-1107. (  0) 0)

|

| [3] |

韩书娜, 刘昆磊, 吕杰. 康复锻炼用肌电控制机械手开发[J]. 机床与液压, 2019, 47(11): 48-52. HAN Shuna, LIU Kunlei, LV Jie. Development of myoelectric control manipulator for rehabilitative exercise[J]. Machine tool & hydraulics, 2019, 47(11): 48-52. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-3881.2019.11.010 (  0) 0)

|

| [4] |

MANERO R B R, SHAFTI A, MICHAEL B, et al. Wearable embroidered muscle activity sensing device for the human upper leg[C]//Proceedings of 2016 38th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Orlando, USA, 2016: 6062–6065.

( 0) 0)

|

| [5] |

JACKSON R W, COLLINS S H. An experimental comparison of the relative benefits of work and torque assistance in ankle exoskeletons[J]. Journal of applied physiology, 2015, 119(5): 541-557. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.01133.2014 ( 0) 0)

|

| [6] |

MULAS M, FOLGHERAITER M, GINI G. An EMG-controlled exoskeleton for hand rehabilitation[C]//Proceedings of 9th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics. Chicago, USA, 2005.

( 0) 0)

|

| [7] |

AMBROSINI E, FERRANTE S, ZAJC J, et al. The combined action of a passive exoskeleton and an EMG-controlled neuroprosthesis for upper limb stroke rehabilitation: first results of the RETRAINER project[C]//Proceedings of 2017 International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics. London, UK, 2017.

( 0) 0)

|

| [8] |

LLOYD D G, BUCHANAN T S. A model of load sharing between muscles and soft tissues at the human knee during static tasks[J]. Journal of biomechanical engineering, 1996, 118(3): 367-376. DOI:10.1115/1.2796019 ( 0) 0)

|

| [9] |

MCGILL S M. A myoelectrically based dynamic three-dimensional model to predict loads on lumbar spine tissues during lateral bending[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 1992, 25(4): 395-414. DOI:10.1016/0021-9290(92)90259-4 ( 0) 0)

|

| [10] |

郭伟, 杨丛为, 邓静, 等. 外骨骼机器人系统中人体下肢关节力矩动态解算[J]. 机械与电子, 2015(10): 71-75. GUO Wei, YANG Cong Wei, DENG Jing, et al. Dynamic solution of the lower extremity joint torques in man-machine system of lower extremity exoskeleton[J]. Machinery & electronics, 2015(10): 71-75. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-2257.2015.10.021 (  0) 0)

|

| [11] |

SONG Jialei, ZHONG Yong, LUO Haoxiang, et al. Hydrodynamics of larval fish quick turning: a computational study[J]. Proceedings of the institution of mechanical engineers, part C: journal of mechanical engineering science, 2018, 232(14): 2515-2523. DOI:10.1177/0954406217743271 ( 0) 0)

|

| [12] |

ZAJAC F E. Muscle and tendon: properties, models, scaling, and application to biomechanics and motor control[J]. Critical reviews in biomedical engineering, 1989, 17(4): 359-411. ( 0) 0)

|

| [13] |

HUXLEY A F. Muscle structure and theories of contraction[J]. Progress in biophysics and biophysical chemistry, 1957, 7: 255-318. DOI:10.1016/S0096-4174(18)30128-8 ( 0) 0)

|

| [14] |

HUXLEY A F, SIMMONS R M. Proposed mechanism of force generation in striated muscle[J]. Nature, 1971, 233(5321): 533-538. DOI:10.1038/233533a0 ( 0) 0)

|

| [15] |

ZAHALAK G I. A comparison of the mechanical behavior of the cat soleus muscle with a distribution-moment model[J]. Journal of biomechanical engineering, 1986, 108(2): 131-140. DOI:10.1115/1.3138592 ( 0) 0)

|

| [16] |

ZAHALAK G I. The two-state cross-bridge model of muscle is an asymptotic limit of multi-state models[J]. Journal of theoretical biology, 2000, 204(1): 67-82. DOI:10.1006/jtbi.2000.1084 ( 0) 0)

|

| [17] |

HILL A V. The heat of shortening and the dynamic constants of muscle[J]. Proceedings of the royal society B: biological sciences, 1938, 126(843): 136-195. ( 0) 0)

|

| [18] |

HAN Jianda, DING Qichuan, XIONG Anbin, et al. A state-space EMG model for the estimation of continuous joint movements[J]. IEEE transactions on industrial electronics, 2015, 62(7): 4267-4275. DOI:10.1109/TIE.2014.2387337 ( 0) 0)

|

| [19] |

BUCHANAN T S, LLOYD D G, MANAL K, et al. Neuromusculoskeletal modeling: estimation of muscle forces and joint moments and movements from measurements of neural command[J]. Journal of applied biomechanics, 2004, 20(4): 367-395. DOI:10.1123/jab.20.4.367 ( 0) 0)

|

| [20] |

MURRAY W M, BUCHANAN T S, DELP S L. The isometric functional capacity of muscles that cross the elbow[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 2000, 33(8): 943-952. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9290(00)00051-8 ( 0) 0)

|

| [21] |

CROUCH D L, HUANG He. Musculoskeletal model predicts multi-joint wrist and hand movement from limited EMG control signals[C]//Proceedings of 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Milan, Italy, 2015.

( 0) 0)

|

| [22] |

LLOYD D G, BESIER T F. An EMG-driven musculoskeletal model to estimate muscle forces and knee joint moments in vivo[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 2003, 36(6): 765-776. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9290(03)00010-1 ( 0) 0)

|

| [23] |

MANAL K, GONZALEZ R V, LLOYD D G, et al. A real-time EMG-driven virtual arm[J]. Computers in biology and medicine, 2002, 32(1): 25-36. DOI:10.1016/S0010-4825(01)00024-5 ( 0) 0)

|

| [24] |

DESPLENTER T, TREJOS A L. Evaluating muscle activation models for elbow motion estimation[J]. Sensors, 2018, 18(4): 1004. DOI:10.3390/s18041004 ( 0) 0)

|

| [25] |

CAVALLARO E E, ROSEN J, PERRY J C, et al. Real-time myoprocessors for a neural controlled powered exoskeleton arm[J]. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering, 2006, 53(11): 2387-2396. DOI:10.1109/TBME.2006.880883 ( 0) 0)

|

| [26] |

MANAL K, BUCHANAN T S. A one-parameter neural activation to muscle activation model: estimating isometric joint moments from electromyograms[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 2003, 36(8): 1197-1202. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9290(03)00152-0 ( 0) 0)

|

| [27] |

CHADWICK E K, BLANA D, KIRSCH R F, et al. Real-time simulation of three-dimensional shoulder girdle and arm dynamics[J]. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering, 2014, 61(7): 1947-1956. DOI:10.1109/TBME.2014.2309727 ( 0) 0)

|

| [28] |

RENGIFO C, AOUSTIN Y, PLESTAN F, et al. Distribution of forces between synergistics and antagonistics muscles using an optimization criterion depending on muscle contraction behavior[J]. Journal of biomechanical engineering, 2010, 132(4): 041009. DOI:10.1115/1.4001116 ( 0) 0)

|

| [29] |

CHADWICK E K, BLANA D, VAN DEN BOGERT A J, et al. A real-time, 3-D musculoskeletal model for dynamic simulation of arm movements[J]. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering, 2009, 56(4): 941-948. DOI:10.1109/TBME.2008.2005946 ( 0) 0)

|

| [30] |

THELEN D G. Adjustment of muscle mechanics model parameters to simulate dynamic contractions in older adults[J]. Journal of biomechanical engineering, 2003, 125(1): 70-77. DOI:10.1115/1.1531112 ( 0) 0)

|

| [31] |

SCHUTTE L M, RODGERS M M, ZAJAC F E, et al. Improving the efficacy of electrical stimulation-induced leg cycle ergometry: an analysis based on a dynamic musculoskeletal model[J]. IEEE transactions on rehabilitation engineering, 1993, 1(2): 109-125. DOI:10.1109/86.242425 ( 0) 0)

|

| [32] |

HERZOG W. History dependence of force production in skeletal muscle: a proposal for mechanisms[J]. Journal of electromyography and kinesiology, 1998, 8(2): 111-117. DOI:10.1016/S1050-6411(97)00027-8 ( 0) 0)

|

| [33] |

GORDON A M, HUXLEY A F, JULIAN F J. The variation in isometric tension with sarcomere length in vertebrate muscle fibres[J]. The journal of physiology, 1966, 184(1): 170-192. DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007909 ( 0) 0)

|

| [34] |

DING Qichan, XIONG Anbin, ZHAO Xingang, et al. A novel EMG-driven state space model for the estimation of continuous joint movements[C]//Proceedings of 2011 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics. Anchorage, USA, 2011.

( 0) 0)

|

| [35] |

CROUCH D L, HUANG H. Musculoskeletal model-based control interface mimics physiologic hand dynamics during path tracing task[J]. Journal of neural engineering, 2017, 14(3): 036008. DOI:10.1088/1741-2552/aa61bc ( 0) 0)

|

| [36] |

AO Di, SONG Rong, GAO Jinwu. Movement performance of human-robot cooperation control based on EMG-driven hill-type and proportional models for an ankle power-assist exoskeleton robot[J]. IEEE transactions on neural systems and rehabilitation engineering, 2017, 25(8): 1125-1134. DOI:10.1109/TNSRE.2016.2583464 ( 0) 0)

|

| [37] |

FORCINITO M, EPSTEIN M, HERZOG W. Can a rheological muscle model predict force depression/enhancement?[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 1998, 31(12): 1093-1099. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9290(98)00132-8 ( 0) 0)

|

| [38] |

KAWAKAMI Y, ICHINOSE Y, FUKUNAGA T. Architectural and functional features of human, triceps surae muscles during contraction[J]. Journal of applied physiology, 1998, 85(2): 398-404. DOI:10.1152/jappl.1998.85.2.398 ( 0) 0)

|

| [39] |

WOITTIEZ R D, HUIJING P A, BOOM H B K, et al. A three-dimensional muscle model: a quantified relation between form and function of skeletal muscles[J]. Journal of morphology, 1984, 182(1): 95-113. DOI:10.1002/jmor.1051820107 ( 0) 0)

|

| [40] |

SCOTT S H, WINTER D A. A comparison of three muscle pennation assumptions and their effect on isometric and isotonic force[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 1991, 24(2): 163-167. DOI:10.1016/0021-9290(91)90361-P ( 0) 0)

|

| [41] |

MENEGALDO L L, DE TOLEDO FLEURY A, WEBER H I. Moment arms and musculotendon lengths estimation for a three-dimensional lower-limb model[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 2004, 37(9): 1447-1453. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.12.017 ( 0) 0)

|

| [42] |

DELP S L, LOAN J P. A graphics-based software system to develop and analyze models of musculoskeletal structures[J]. Computers in biology and medicine, 1995, 25(1): 21-34. DOI:10.1016/0010-4825(95)98882-E ( 0) 0)

|

| [43] |

DELP S L, LOAN J P, HOY M G, et al. An interactive graphics-based model of the lower extremity to study orthopaedic surgical procedures[J]. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering, 1990, 37(8): 757-767. DOI:10.1109/10.102791 ( 0) 0)

|

| [44] |

DE GROOTE F, VAN CAMPEN A, JONKERS I, et al. Sensitivity of dynamic simulations of gait and dynamometer experiments to hill muscle model parameters of knee flexors and extensors[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 2010, 43(10): 1876-1883. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.03.022 ( 0) 0)

|

| [45] |

REDL C, GFOEHLER M, PANDY M G. Sensitivity of muscle force estimates to variations in muscle–tendon properties[J]. Human movement science, 2007, 26(2): 306-319. DOI:10.1016/j.humov.2007.01.008 ( 0) 0)

|

| [46] |

AI Qingsong, DING Bo, LIU Quan, et al. A subject-specific EMG-driven musculoskeletal model for applications in lower-limb rehabilitation robotics[J]. International journal of humanoid robotics, 2016, 13(3): 1650005. DOI:10.1142/S0219843616500055 ( 0) 0)

|

| [47] |

MENEGALDO L L, OLIVEIRA L F. The influence of modeling hypothesis and experimental methodologies in the accuracy of muscle force estimation using EMG-driven models[J]. Multibody system dynamics, 2012, 28(1/2): 21-36. ( 0) 0)

|

| [48] |

QASHQAI A, EHSANI H, ROSTAMI M. A hill-based EMG-driven model to estimate elbow torque during flexion and extention[C]//Proceedings of 2015 22nd Iranian Conference on Biomedical Engineering. Tehran, Iran, 2015.

( 0) 0)

|

| [49] |

LI Kexiang, ZHANG Jianhua, LIU Xuan, et al. Estimation of continuous elbow joint movement based on human physiological structure[J]. Biomedical engineering online, 2019, 18(1): 31. DOI:10.1186/s12938-019-0653-2 ( 0) 0)

|

| [50] |

PAU J W L, SAINI H, XIE S S Q, et al. An EMG-driven neuromuscular interface for human elbow joint[C]//Proceedings of 2010 3rd IEEE RAS & EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics. Tokyo, Japan, 2010.

( 0) 0)

|

| [51] |

HOLZBAUR K R S, MURRAY W M, DELP S L. A model of the upper extremity for simulating musculoskeletal surgery and analyzing neuromuscular control[J]. Annals of biomedical engineering, 2005, 33(6): 829-840. DOI:10.1007/s10439-005-3320-7 ( 0) 0)

|

| [52] |

SON J, HWANG S J, LEE J S, et al. Optimization of muscle parameters to predict ankle joint moments[C]//Proceedings of 6th World Congress of Biomechanics. Singapore, 2010.

( 0) 0)

|

| [53] |

BUONGIORNO D, BARSOTTI M, BARONE F, et al. A linear approach to optimize an EMG-Driven Neuromusculoskeletal model for movement intention detection in myo-control: a case study on shoulder and elbow joints[J]. Frontiers in neurorobotics, 2018, 12: 74. DOI:10.3389/fnbot.2018.00074 ( 0) 0)

|

| [54] |

MICHALEWICZ Z, NAZHIYATH G. Genocop III: a co-evolutionary algorithm for numerical optimization problems with nonlinear constraints[C]//Proceedings of 1995 IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation. Perth, WA, Australia, 1995.

( 0) 0)

|

| [55] |

SON J, KIM S, AHN S, et al. Determination of the dynamic knee joint range of motion during leg extension exercise using an EMG-driven model[J]. International journal of precision engineering and manufacturing, 2012, 13(1): 117-123. DOI:10.1007/s12541-012-0016-4 ( 0) 0)

|

| [56] |

AN K N, HUI F C, MORREY B F, et al. Muscles across the elbow joint: a biomechanical analysis[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 1981, 14(10): 659-661, 663-669. DOI:10.1016/0021-9290(81)90048-8 ( 0) 0)

|

| [57] |

JACOBSON M D, RAAB R, FAZELI B M, et al. Architectural design of the human intrinsic hand muscles[J]. The journal of hand surgery, 1992, 17(5): 804-809. DOI:10.1016/0363-5023(92)90446-V ( 0) 0)

|

| [58] |

LANGENDERFER J, JERABEK S A, THANGAMANI V B, et al. Musculoskeletal parameters of muscles crossing the shoulder and elbow and the effect of sarcomere length sample size on estimation of optimal muscle length[J]. Clinical biomechanics, 2004, 19(7): 664-670. DOI:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2004.04.009 ( 0) 0)

|

| [59] |

LIEBER R L, FAZELI B M, BOTTE M J. Architecture of selected wrist flexor and extensor muscles[J]. The journal of hand surgery, 1990, 15(2): 244-250. DOI:10.1016/0363-5023(90)90103-X ( 0) 0)

|

| [60] |

LIEBER R L, JACOBSON M D, FAZELI B M, et al. Architecture of selected muscles of the arm and forearm: anatomy and implications for tendon transfer[J]. The journal of hand surgery, 1992, 17(5): 787-798. DOI:10.1016/0363-5023(92)90444-T ( 0) 0)

|

| [61] |

JIANG Ning, ENGLEHART K B, PARKER P A. Extracting simultaneous and proportional neural control information for multiple-DOF prostheses from the surface electromyographic signal[J]. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering, 2009, 56(4): 1070-1080. DOI:10.1109/TBME.2008.2007967 ( 0) 0)

|

| [62] |

DOWLING D J. The use of electromyography for the noninvasive prediction of muscle forces[J]. Sports medicine, 1997, 24(2): 82-96. DOI:10.2165/00007256-199724020-00002 ( 0) 0)

|

| [63] |

RASCHKE U, CHAFFIN D B. Support for a linear length-tension relation of the torso extensor muscles: an investigation of the length and velocity EMG-force relationships[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 1996, 29(12): 1597-1604. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9290(96)80011-X ( 0) 0)

|

| [64] |

ROSEN J, BRAND M, FUCHS M B, et al. A myosignal-based powered exoskeleton system[J]. IEEE transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics-Part A: systems and humans, 2001, 31(3): 210-222. DOI:10.1109/3468.925661 ( 0) 0)

|

| [65] |

MANAL K, GRAVARE-SILBERNAGEL K, BUCHANAN T S. A real-time EMG-driven musculoskeletal model of the ankle[J]. Multibody system dynamics, 2012, 28(1/2): 169-180. ( 0) 0)

|

| [66] |

ROSEN J, FUCHS M B, ARCAN M. Performances of hill-type and neural network muscle models—toward a myosignal-based exoskeleton[J]. Computers and biomedical research, 1999, 32(5): 415-439. DOI:10.1006/cbmr.1999.1524 ( 0) 0)

|

| [67] |

MENEGALDO L L, OLIVEIRA L F. An EMG-driven model to evaluate quadriceps strengthening after an isokinetic training[J]. Procedia IUTAM, 2011, 2: 131-141. DOI:10.1016/j.piutam.2011.04.014 ( 0) 0)

|

| [68] |

MENEGALDO L L. Real-time muscle state estimation from EMG signals during isometric contractions using Kalman filters[J]. Biological cybernetics, 2017, 111(5/6): 335-346. ( 0) 0)

|

| [69] |

MA Ye, XIE Shengquan, ZHANG Yanxin. A patient-specific EMG-driven neuromuscular model for the potential use of human-inspired gait rehabilitation robots[J]. Computers in biology and medicine, 2016, 70: 88-98. DOI:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2016.01.001 ( 0) 0)

|

| [70] |

WANG He, ZHANG Xiaodong, CHEN Jiangcheng, et al. Realization of human-computer interaction of lower limbs rehabilitation robot based on sEMG[C]//Proceedings of the 4th Annual IEEE International Conference on Cyber Technology in Automation. Hong Kong, China, 2014: 491–495.

( 0) 0)

|

| [71] |

SHAO Qi, BASSETT D N, MANAL K, et al. An EMG-driven model to estimate muscle forces and joint moments in stroke patients[J]. Computers in biology and medicine, 2009, 39(12): 1083-1088. DOI:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2009.09.002 ( 0) 0)

|

| [72] |

PIZZOLATO C, LLOYD D G, SARTORI M, et al. CEINMS: a toolbox to investigate the influence of different neural control solutions on the prediction of muscle excitation and joint moments during dynamic motor tasks[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 2015, 48(14): 3929-3936. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.09.021 ( 0) 0)

|

| [73] |

ZHUANG Yu, YAO Shaowei, MA Chenming, et al. Admittance control based on EMG-driven musculoskeletal model improves the human-robot synchronization[J]. IEEE transactions on industrial informatics, 2018, 15(2): 1211-1218. ( 0) 0)

|

| [74] |

LLOYD D G, BUCHANAN T S. Strategies of muscular support of varus and valgus isometric loads at the human knee[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 2001, 34(10): 1257-1267. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00095-1 ( 0) 0)

|

| [75] |

OLNEY S J, WINTER D A. Predictions of knee and ankle moments of force in walking from EMG and kinematic data[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 1985, 18(1): 9-20. DOI:10.1016/0021-9290(85)90041-7 ( 0) 0)

|

| [76] |

RAJAGOPAL A, DEMBIA C L, DEMERS M S, et al. Full-body musculoskeletal model for muscle-driven simulation of human gait[J]. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering, 2016, 63(10): 2068-2079. DOI:10.1109/TBME.2016.2586891 ( 0) 0)

|

| [77] |

HOANG H X, DIAMOND L E, LLOYD D G, et al. A calibrated EMG-informed neuromusculoskeletal model can appropriately account for muscle co-contraction in the estimation of hip joint contact forces in people with hip osteoarthritis[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 2019, 83: 134-142. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2018.11.042 ( 0) 0)

|

| [78] |

BUCHANAN T S, MONIZ M J, DEWALD J P A, et al. Estimation of muscle forces about the wrist joint during isometric tasks using an EMG coefficient method[J]. Journal of biomechanics, 1993, 26(4/5): 547-560. ( 0) 0)

|

| [79] |

VAN DEN BOGERT A J, BLANA D, HEINRICH D. Implicit methods for efficient musculoskeletal simulation and optimal control[J]. Procedia IUTAM, 2011, 2: 297-316. DOI:10.1016/j.piutam.2011.04.027 ( 0) 0)

|

| [80] |

BUENO D R, MONTANO L. Neuromusculoskeletal model self-calibration for on-line sequential Bayesian moment estimation[J]. Journal of neural engineering, 2017, 14(2): 026011. DOI:10.1088/1741-2552/aa58f5 ( 0) 0)

|

2020, Vol. 15

2020, Vol. 15