扩展功能

文章信息

- 赵芳, 林恭华, 吴爱国

- ZHAO Fang, LIN Gonghua, WU Aiguo

- 河流对黄胸鼠遗传格局的影响

- Influence of Riverine Barriers on Genetic Structure of Rattus tanezumi

- 四川动物, 2016, 35(2): 167-172

- Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2016, 35(2): 167-172

- 10.11984/j.issn.1000-7083.20150286

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2015-09-18

- 接受日期: 2015-11-04

2. 云南省地方病防治所, 云南大理 671000

2. Yunnan Institute of Endemic Disease Control and Prevention, Dali, Yunnan Province 671000, China

河流屏障假说(riverine barrier hypothesis)认为,河流作为一种地理隔离,可能会阻碍陆生动物的迁移以及基因流动,从而引起种群分化,促进种群格局的形成(Gascon et al.,2000;Hayes & Sewlal,2004;Li et al.,2009)。针对这一假说,前人的研究得到了2种完全对立的结论。通过对哺乳动物、鸟类、爬行动物、两栖动物和昆虫的反复验证,大多数的研究支持这一假说(Knopp et al.,2011;Díaz-Muñoz,2012;Fernandes et al.,2012)。然而,少数研究并不认为河流能构成影响陆生动物种群格局的屏障。例如,对法国阿尔卑斯山脉中山溪两岸的一些鼩鼱Sorex araneus遗传结构的研究证明,这些山溪并没有明显影响鼩鼱的基因流(Lugon-moulin et al.,1999)。

大家鼠属Rattus现存66个物种,广泛分布于全球各地,通常被认为是迁移扩散能力最强的哺乳动物之一(Wilson & Reeder,2005)。作为各种鼠传病菌(如鼠疫杆菌Yersinia pestis)和体外寄生虫(如跳蚤)最重要的宿主,它们是各种重大动物疾病的元凶(Pagès et al.,2010),而且还会严重破坏生活环境内的建筑物,并且污染和毁坏人类的粮食储存(Hinds et al.,2003)。因此,了解大家鼠属生物多样性形成的机制对疾病的预防和鼠害的防控至关重要。

黄胸鼠Rattus tanezumi是主要分布在东南亚的大家鼠,其生境广泛,包括城区、农村、农田以及森林边缘(Wilson & Reeder,2005),因携带很多鼠传病菌和对人类设施巨大的破坏力而臭名昭著(郑智民等,2008),其中最为人们所熟悉的是,它们是东南亚鼠疫的主要宿主(贺雄,王虎,2010)。黄胸鼠主要分布在热带和亚热带地区,这些地区的大江大河常年不结冰。然而,这些河流是否能影响黄胸鼠的种群遗传分化,目前还没有系统的调查和分析资料。本研究中,我们从云南省捕获了一定数量的黄胸鼠,以线粒体基因和核基因共同作为分子标记来验证云南省内5条大江(怒江、澜沧江、李仙江、元江和南盘江)对黄胸鼠种群遗传格局的影响。

1 材料和方法 1.1 样品采集、DNA提取、基因扩增和测序用活捕笼(20 cm×12 cm×9 cm)捕获黄胸鼠,乙醚麻醉,断颈法处死并收集大腿内侧肌肉样品,保存在95%乙醇中,带回实验室用于分子实验。

采用动物组织基因组DNA提取试剂盒(Qiagen,Germany)提取基因组DNA。根据黄胸鼠线粒体基因组序列(GenBank登录号:KF011916)设计扩增线粒体部分序列的引物:mtDNA-F:5 ’-ACCCTACTTACTGGCTTCA-3 ’;mtDNA-R:5 ’-TAATGGCGAATACTGCTC-3 ’。mtDNA包含完整的tRNA-Tyr基因和细胞色素C氧化酶Ⅰ基因(cytochrome c oxidase subunit Ⅰ,COⅠ)的部分序列。类视黄醇结合蛋白(interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein,IRBP)部分序列的引物根据已发表的黄胸鼠IRBP序列(GenBank登录号:HM217693)设计:IRBP-F:5 ’-CTATGAGCCCAGTACCCTCG-3 ’;IRBP-R:5 ’-AGCACGGACACCTGAAACA-3 ’。

PCR扩增使用40 μL反应体系,包括:40~60 ng的基因组DNA,0.6 mmol·L-1 dNTPs,0.2 μmol·L-1的正/反向引物,1 U Taq酶,以及DNA buffer和去离子水的混合反应缓冲液。PCR反应程序是:95 ℃预变性5 min;94 ℃变性45 s,55 ℃退火45 s,72 ℃延伸75 s,35个循环;最后72 ℃延伸7 min。PCR产物用CASpure PCR Purification Kit(Casarray,Shanghai,China)纯化,用PCR扩增引物进行Sanger法测序 。

1.2 谱系地理学分析用MEGA 5(Tamura et al.,2011)中内嵌的Clustal W(Tompson et al.,1997)程序比对测序得到的序列,辅以人工校对。用DnaSP 5(Librado & Rozas,2009)分析mtDNA的变异位点和单倍型的分布。由于IRBP基因为二倍体序列,其中有很多单核苷酸多态性(single nucleotide polymorphisms,SNPs)位点,我们首先使用DnaSP 5中的PHASE 2.1(Stephens et al.,2001)程序构建单倍型,然后基于这些单倍型进行变异位点和遗传结构分析。

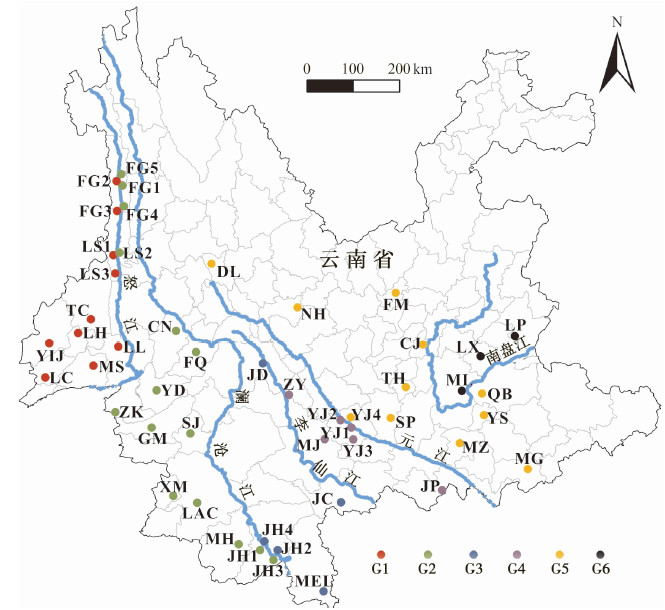

为了推断河流对黄胸鼠谱系地理学特征的影响,按照5条河流的分隔,将采样地点划分为6个地理区域分组(G1~G6,图 1)。用Arlequin 3.11(Excoffier & Lischer,2005)进行分子方差分析(analyses of molecular variance,AMOVA),分别计算区域之间、区域内种群之间和种群内部的方差百分比。

|

|

图 1 黄胸鼠样本及地理分布

Fig. 1 Geographic distribution and grouping of Rattus tanezumi

缩写见表1中地点编号;下图同。 Abbreviations are the same as the locality ID in table 1; the same below. |

同时用SAMOVA v1.0(Dupanloup et al.,2002)对黄胸鼠种群进行谱系地理结构聚类。组数K值的设定从2到6,置换500次。判定标准为:在避免某一组只有单个种群的前提下,FCT值最大且P值有统计学意义的分组为最好的种群分组(Magri et al.,2006;Shi et al.,2012)。

2 结果从云南省38个县50个地点共捕获384只黄胸鼠,地点信息详见表 1和图 1。测序结果显示,比对好的mtDNA序列总长1 182 bp(File S1),有93个多态位点,81个单倍型(mH1~mH81;File S2);IRBP基因总长932 bp(File S3),包括45个变异位点和135个通过PHASE软件分离的SNP单倍型(iH1~iH135;File S4)。mtDNA和IRBP基因的单倍型分布情况详见Table S1。以上所有附属文件可在Dryad数据库中下载(http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.584kb),或联系作者邮件索取。

| 县County | 地点编号Locality ID | 纬度Latitude/° | 经度Longitude/° | 样本大小Sample size | 地理区域编号Geographic group ID |

| 澄江 Chengjiang | CJ | 24.689 70 | 102.982 80 | 4 | G5 |

| 昌宁 Changning | CN | 24.874 91 | 99.644 67 | 10 | G2 |

| 大理 Dali | DL | 25.783 17 | 100.126 44 | 7 | G5 |

| 福贡 Fugong | FG1 | 26.860 44 | 98.871 80 | 5 | G2 |

| 福贡 Fugong | FG2 | 26.890 81 | 98.871 51 | 8 | G1 |

| 福贡 Fugong | FG3 | 26.495 52 | 98.897 28 | 9 | G1 |

| 福贡 Fugong | FG4 | 26.540 11 | 98.897 18 | 3 | G2 |

| 福贡 Fugong | FG5 | 26.981 15 | 98.864 27 | 2 | G2 |

| 富民 Fumin | FM | 25.388 48 | 102.612 07 | 6 | G5 |

| 凤庆 Fengqing | FQ | 24.590 11 | 99.914 53 | 10 | G2 |

| 耿马 Gengma | GM | 23.571 26 | 99.317 34 | 10 | G2 |

| 江城 Jiangcheng | JC | 22.561 00 | 101.872 82 | 9 | G3 |

| 景东 Jingdong | JD | 24.455 62 | 100.834 78 | 9 | G3 |

| 景洪 Jinghong | JH1 | 21.914 90 | 100.780 87 | 10 | G2 |

| 景洪 Jinghong | JH2 | 21.869 97 | 100.990 59 | 9 | G3 |

| 景洪 Jinghong | JH3 | 21.841 72 | 100.979 61 | 8 | G2 |

| 景洪 Jinghong | JH4 | 22.015 90 | 100.811 07 | 9 | G3 |

| 金平 Jinping | JP | 22.723 40 | 103.238 00 | 2 | G4 |

| 澜沧 Lancang | LAC | 22.556 07 | 99.932 30 | 9 | G2 |

| 陇川 Longchuan | LC | 24.247 65 | 97.879 64 | 10 | G1 |

| 梁河 Lianghe | LH | 24.846 86 | 98.324 51 | 10 | G1 |

| 龙陵 Longling | LL | 24.662 60 | 98.867 06 | 9 | G1 |

| 罗平 Luoping | LP | 24.806 35 | 104.222 61 | 8 | G6 |

| 泸水 Lushui | LS1 | 25.908 14 | 98.841 87 | 8 | G1 |

| 泸水 Lushui | LS2 | 25.914 49 | 98.831 43 | 9 | G2 |

| 泸水 Lushui | LS3 | 25.649 92 | 98.883 50 | 9 | G1 |

| 泸西 Luxi | LX | 24.534 33 | 103.759 77 | 1 | G6 |

| 勐腊 Mengla | MEL | 21.360 60 | 101.636 36 | 11 | G3 |

| 马关 Maguan | MG | 23.012 47 | 104.398 36 | 8 | G5 |

| 勐海 Menghai | MH | 21.994 88 | 100.490 34 | 8 | G2 |

| 墨江 Mojiang | MJ | 23.415 14 | 101.653 69 | 5 | G4 |

| 弥勒 Mile | ML | 24.065 58 | 103.505 03 | 9 | G6 |

| 芒市 Mangshi | MS | 24.406 63 | 98.531 48 | 8 | G1 |

| 蒙自 Mengzi | MZ | 23.360 49 | 103.479 32 | 3 | G5 |

| 南华 Nanhua | NH | 25.192 03 | 101.287 60 | 8 | G5 |

| 丘北 Qiubei | QB | 24.030 23 | 103.778 90 | 10 | G5 |

| 双江 Shuangjiang | SJ | 23.491 36 | 99.838 19 | 8 | G2 |

| 石屏 Shiping | SP | 23.700 24 | 102.545 17 | 13 | G5 |

| 腾冲 Tengchong | TC | 25.031 59 | 98.496 57 | 10 | G1 |

| 通海 Tonghai | TH | 24.117 88 | 102.749 56 | 7 | G5 |

| 西盟 Ximeng | XM | 22.647 26 | 99.607 52 | 10 | G2 |

| 永德 Yongde | YD | 24.074 44 | 99.383 33 | 8 | G2 |

| 盈江 Yingjiang | YIJ | 24.708 05 | 97.932 54 | 10 | G1 |

| 元江 Yuanjiang | YJ1 | 23.569 01 | 102.014 46 | 2 | G4 |

| 元江 Yuanjiang | YJ2 | 23.669 99 | 101.868 41 | 2 | G4 |

| 元江 Yuanjiang | YJ3 | 23.410 32 | 102.040 20 | 4 | G4 |

| 元江 Yuanjiang | YJ4 | 23.711 86 | 102.006 17 | 7 | G5 |

| 砚山 Yanshan | YS | 23.738 36 | 103.806 61 | 10 | G5 |

| 镇康 Zhenkang | ZK | 23.775 77 | 98.825 87 | 10 | G2 |

| 镇沅 Zhenyuan | ZY | 24.005 38 | 101.107 06 | 10 | G4 |

AMOVA分析显示,对于mtDNA而言,超过50%的变异源于种群内部,只有13.33%源于区域之间(即G1~G6之间)。对于IRBP,大多数变异(88.12%)源于种群内部,仅有4.62%源于区域之间(表 2)。

| 基因Gene | 自由度df | 变异来源Source of variation | 变异百分比Percentage of variation/% |

| mtDNA | 5 | 区域间 | 13.33 |

| 44 | 种群间 | 33.04 | |

| 334 | 种群内 | 53.63 | |

| IRBP | 5 | 区域间 | 4.62 |

| 44 | 种群间 | 7.26 | |

| 718 | 种群内 | 88.12 |

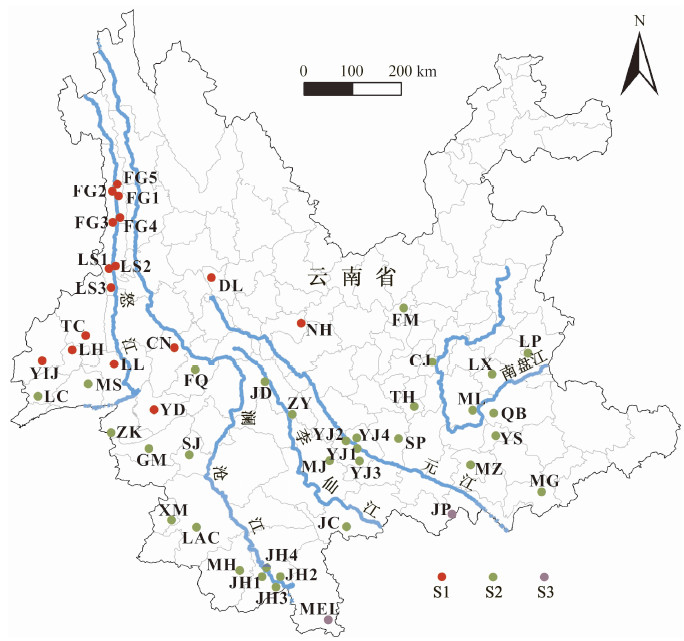

SAMOVA分析显示,对mtDNA而言,K值越大,FCT值越大。但是,当K>3时,会存在某些分组内只有一个种群的情况。因此,K=3时的模型属于最佳模型,此模型的3个分组(S1~S3)分别包含32个、16个和2个种群(图 2)。对IRBP而言,FCT值随着K值的增大而减小,同时也存在某些分组只有一个种群的情况,因此,基于IRBP数据无法得到明显的种群结构(表 3)。

|

| 图 2 基于mtDNA 的50个黄胸鼠种群的SAMOVA分组 Fig. 2 SAMOVA grouping of the 50 Rattus tanezumi populations based on mtDNA sequences |

| 基因Gene | K值 K-value | 分组预测Structure tested | 变异来源Source of variation | 固定指数F CT | ||

| AG | AP | WP | ||||

| mtDNA | 2 | 42+18 | 46.11 | 11.73 | 42.16 | 0.461 1 |

| 3 | 32+16+2 | 47.62 | 10.05 | 42.32 | 0.476 3 | |

| 4 | 32+15+2+1 | 49.26 | 8.52 | 42.22 | 0.492 6 | |

| 5 | 32+14+2+1+1 | 49.78 | 7.73 | 42.49 | 0.497 8 | |

| 6 | 32+13+2+1+1+1 | 50.13 | 7.09 | 42.78 | 0.501 3 | |

| IRBP | 2 | 49+1 | 34.50 | 7.08 | 58.42 | 0.345 0 |

| 3 | 48+1+1 | 19.00 | 8.68 | 72.32 | 0.190 0 | |

| 4 | 47+1+1+1 | 14.32 | 8.74 | 76.94 | 0.143 2 | |

| 5 | 46+1+1+1+1 | 13.57 | 8.74 | 77.70 | 0.135 7 | |

| 6 | 43+3+1+1+1+1 | 13.14 | 7.51 | 79.35 | 0.131 4 | |

| 注: AG. 组间, AP. 种群间, WP. 种群内。 Notes: AG. among groups, AP. among populations within group, WP. within population. |

||||||

本研究检验了河流屏障对黄胸鼠种群遗传的影响。单倍型分布分析显示,河流对地理区域(G1~G6)组间的单倍型分布没有 明显的影响。总的来说,81个mtDNA单倍型中有15个是2个或2个以上区域共享的。例如,G2~G6共享mH3单倍型。同时,在135个IRBP单倍型中,有49个被2个或2个以上区域共享,其中,iH47和iH65为所有区域共享(详见Table S1)。

AMOVA分析显示,无论是mtDNA还是IRBP,都只有少数变异源于6个区域之间(分别为13.33%和4.67%),表明5条河流对黄胸鼠种群遗传变异的屏障作用不明显。同时,基于mtDNA的SAMOVA分析也显示所有种群被分成了3组(S1~S3),且每一个SAMOVA分组都被2条或以上河流分隔开,换句话说,每个SAMOVA分组都不是单独位于某一区域内。此外,基于IRBP的SAMOVA分析证明没有明显的种群结构存在。综合来看,所有结果都表明云南省5条主要河流对黄胸鼠种群遗传格局的形成影响很小。

由于对各种生境的适应能力很强,以及高效的迁移和繁殖能力,大家鼠一直被认为是最具有侵略性扩张能力的哺乳动物之一。本属的很多动物在有需要时都会游泳,褐家鼠R. norvegicus的游泳能力(能在水中呆3 d或游0.75 km)在很多文献中被反复证明(Russell et al.,2008)。也有文献(Innes,2005;Shiels et al.,2014)证明屋顶鼠R. rattus能游300~750 m到邻近的岛屿上。作为与屋顶鼠亲缘关系最近的黄胸鼠,我们有理由相信它们也是游泳能手。事实上,在福贡县采样时,当地居民告诉我们黄胸鼠有时候甚至能横游过怒江(个人交流)。云南省5条主要河流的宽度一般都不超过200 m,我们假设黄胸鼠能够轻易游过这几条河流的话,也就证明了对黄胸鼠而言,河流不存在屏障效应。

除了游泳外,黄胸鼠还可能通过船只往来进行迁移(Russell et al.,2008)。由于交通业的发展,目前世界上大部分地区都有褐家鼠和屋顶鼠的分布(Krinke,2000;Aplin et al.,2011)。在中国,火车运输对黄胸鼠在各个省份之间的迁移扮演了重要的角色(张美文等,2000)。同时,桥梁也为黄胸鼠横跨河流两岸提供了路径,然而这些跨河交通及设施究竟如何影响黄胸鼠的种群遗传结构,则需要进一步研究。

| 贺雄, 王虎. 2010. 现代鼠疫概论[M]. 北京: 科学出版社. |

| 张美文, 郭聪, 王勇, 等. 2000. 我国黄胸鼠的研究现状[J]. 动物学研究, 21(6): 487-497. |

| 郑智民, 姜志宽, 陈安国. 2008. 啮齿动物学[M]. 上海: 上海交通大学出版社. |

| Aplin KP, Suzuki H, Chinen AA, et al. 2011. Multiple geographic origins of commensalism and complex dispersal history of black rats[J]. PLoS ONE, 6(11): e26357. |

| Díaz-Muñoz SL. 2012. Role of recent and old riverine barriers in fine-scale population genetic structure of Geoffroy's tamarin (Saguinus geoffroyi) in the Panama Canal watershed[J]. Ecology and Evolution, 2(2): 298-309. |

| Dupanloup I, Schneider S, Excoffier L. 2002. A simulated annealing approach to define the genetic structure of populations[J]. Molecular Ecology, 11: 2571-2581. |

| Excoffier L, Lischer HL. 2010. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows[J]. Molecular Ecology Resources, 10: 564-567. |

| Fernandes AM, Wink M, Aleixo A. 2012. Phylogeography of the chestnut-tailed antbird (Myrmeciza hemimelaena) clarifies the role of rivers in Amazonian biogeography[J]. Journal of Biogeography, 39(8):1524-1535. |

| Gascon C, Malcolm JR, Patton JL, et al. 2000. Riverine barriers and the geographic distribution of Amazonian species[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 97(25): 13672-13677. |

| Hayes FE, Sewlal JAN. 2004. The Amazon River as a dispersal barrier to passerine birds: effects of river width, habitat and taxonomy[J]. Journal of Biogeography, 31(11): 1809-1818. |

| Hinds LA, Krebs CJ, Spratt DM. 2003. Rats, mice and people: rodent biology and management[M]. Canberra, Australia: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. |

| Innes JG. 2005. Ship rat[M].//King CA. The handbook of New Zealand mammals 2nd edition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press: 187-203. |

| Knopp T, Rahagalala P, Miinala M, et al. 2011. Current geographical ranges of Malagasy dung beetles are not delimited by large rivers[J]. Journal of Biogeography, 38(6): 1098-1108. |

| Krinke GJ. 2000. The laboratory rat[M]. San Diego, USA: Academic Press. |

| Li R, Chen W, Tu L, et al. 2009. Rivers as barriers for high elevation amphibians: a phylogeographic analysis of the alpine stream frog of the Hengduan Mountains[J]. Journal of Zoology, 277(4): 309-316. |

| Librado P, Rozas J. 2009. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data[J]. Bioinformatics, 25: 1451-1452. |

| Lugon-moulin N, Bruenner H, Balloux F, et al. 1999. Do riverine barriers, history or introgression shape the genetic structuring of a common shrew (Sorex araneus) population?[J]. Heredity, 83: 155-161. |

| Magri D, Vendramin GG, Comps B, et al. 2006. A new scenario for the quaternary history of European beech populations: palaeobotanical evidence and genetic consequences[J]. New Phytologist, 171: 199-221. |

| Pagès M, Chaval Y, Herbreteau V, et al. 2010. Revisiting the taxonomy of the Rattini tribe: a phylogeny-based delimitation of species boundaries[J]. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 10(1): 184. |

| Russell JC, Towns DR, Clout MN. 2008. Review of rat invasion biology: implications for island biosecurity (Science for Conservation 286) [M]. Wellington, NZ: Science & Technical Publishing. |

| Shi W, Kerdelhué C, Ye H. 2012. Genetic structure and inferences on potential source areas for Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) based on mitochondrial and microsatellite markers[J]. PLoS ONE, 7(5): e37083. |

| Shiels AB, William CP, Robert TS, et al. 2014. Biology and impacts of pacific island invasive species. 11. Rattus rattus, the black rat (Rodentia: Muridae)[J]. Pacific Science, 68(2): 145-184. |

| Stephens M, Smith NJ, Donnelly P. 2001. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data[J]. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 68: 978-989. |

| Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, et al. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods[J]. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 28(10): 2731-2739. |

| Tompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, et al. 1997. The Clustal X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 25(24): 4876-4882. |

| Wilson DE, Reeder DA. 2005. Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference[M]. Baltimore, USA: John Hopkins University Press. |

2016, Vol. 35

2016, Vol. 35