The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- XU, Zhiqing, Ke FAN, and Huijun WANG, 2019.

- Springtime Convective Quasi-Biweekly Oscillation and Interannual Variation of Its Intensity over the South China Sea and Western North Pacific. 2019.

- J. Meteor. Res., 33(2): 323-335

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-019-8167-1

Article History

- Received November 6, 2018

- in final form December 24, 2018

2. Climate Change Research Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029;

3. University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049;

4. Collaborative Innovation Center on Forecast and Evaluation of Meteorological Disasters, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, Nanjing 210044

Atmospheric 10–20-day intraseasonal oscillation, termed as quasi-biweekly oscillation (QBWO), over the South China Sea–western North Pacific (SCS–WNP) region is significant in summer (Chen and Chen, 1995; Fukutomi and Yasunari, 1999; Li and Wang, 2005; Kikuchi and Wang, 2009; Chen and Wang, 2017). It has a remarkable impact on weather and climate in the Asian monsoon region (e.g., Mao and Chan, 2005; Jia and Yang, 2013; Li and Zhou, 2013; Ren et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2015). Interannual and interdecadal variations of the atmospheric QBWO intensity over the SCS–WNP region in summer, which is an important issue when dealing with its weather and climate impacts, have been studied in previous works (e.g., Zveryaev, 2002; Teng and Wang, 2003; Lin and Li, 2008; Yang et al., 2008; Li et al., 2015; Hsu et al., 2017; Wu and Cao, 2017; Xu et al., 2017). In summer, a westward- or northwestward-propa-gating atmospheric QBWO dominates over the Asian monsoon region, which is closely related to equatorial Rossby waves (e.g., Chatterjee and Goswami, 2004; Kikuchi and Wang, 2009; Chen and Sui, 2010). Therefore, over the SCS–WNP region, background atmospheric-field anomalies (e.g., moisture and vertical zonal wind shear) may influence equatorial Rossby waves (Wang and Xie, 1996; Xie and Wang, 1996) and subsequently modulate the atmospheric QBWO intensity. For example, developing El Niño events leads to anomalous background atmospheric fields (easterly vertical shear, increased lower-level moisture, and enhanced convection) in a region extending from the equatorial western and central Pacific to tropical WNP in summer, favoring the enhanced atmospheric QBWO intensity over the tropical WNP (Wu and Cao, 2017). The Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation shifted to a negative phase around the late 1990s, leading to the decreased background lower-level moisture and anomalous background westerly vertical shear over the WNP in late summer (Xu et al., 2017). As a result, atmospheric QBWO intensity over the WNP in late summer has weakened significantly since the late 1990s.

As described above, previous studies mainly focused on the atmospheric QBWO and variation of its intensity over the SCS–WNP region in summer. However, less attention has been paid to these aspects in spring, which may also have an important impact on weather and climate (e.g., Zhou and Chan, 2005; Wu, 2018). Some studies documented the origin and structure of atmospheric QBWO over the tropical Indian Ocean in spring (Wen and Zhang, 2008; Wen et al., 2010); however, details regarding characteristics of the atmospheric QBWO over the SCS–WNP region remain to be demonstrated. Seasonal evolution of the atmospheric 20–80-day intraseasonal oscillation intensity in the tropics during the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle has been revealed by previous studies (e.g., Gushchina and Dewitte, 2012; Yuan et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). For example, Yuan et al. (2015) showed that there is a strong atmospheric 30–60-day intraseasonal oscillation in the equatorial western Pacific as well as pronounced eastward-propagating signals in the tropics in spring of central and eastern Pacific El Niño developing years, and these features can also be observed in spring of central Pacific El Niño decaying years. However, less attention has been paid to the connection between the atmospheric QBWO intensity over the SCS and WNP in spring and background sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in the tropical Pacific and underlying mechanisms involved (Wu, 2018; Wu and Song, 2018). Wu and Song (2018) revealed that the atmospheric QBWO intensity over the SCS–WNP region tends to enhance (weaken) in connection with anomalous background atmospheric fields in spring of La Niña (fast El Niño) decaying years. However, the dominant mode of interannual variation of the atmospheric QBWO intensity over the SCS–WNP region in spring and its connection with background SST anomalies in the tropical Pacific remains unknown. Besides, outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) is usually employed to trace atmospheric QBWO. Therefore, atmospheric QBWO usually refers to convective QBWO. In fact, variables other than OLR, such as vertical relative vorticity (e.g., Chen and Sui, 2010), can also be used to trace atmospheric QBWO. However, few studies demonstrate the relationship of QBWO intensities of different atmospheric variables in the troposphere.

This study, with the convective QBWO as its main focus, aims to address some of the knowledge gaps described above. The data and methods used are described in Section 2. Section 3 demonstrates the characteristics of convective QBWO over the SCS–WNP region in spring. Section 4 presents the interannual variation of its intensity. The conclusions are provided in Section 5.

2 Data and methodsThe data employed in this study are: (1) daily OLR, with a horizontal resolution of 2.5° × 2.5° (Liebmann and Smith, 1996), provided by the NOAA; (2) 6-hourly and monthly reanalysis data from ERA-Interim, with a horizontal resolution of 1.5° × 1.5° (Dee et al., 2011); (3) the NOAA Extended Reconstructed SST, version 3b, with a horizontal resolution of 2.0° × 2.0° (Smith et al., 2008); and (4) the Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) monthly precipitation, with a horizontal resolution of 2.5° × 2.5° (Adler et al., 2003).

The Lanczos band-pass filter (Duchon, 1979) is applied to the anomalies of daily data to extract the 10–20-day signals. Due to the cutoff of the Lanczos band-pass filter, the period 1980–2016 is used in this study. Spring refers to the months of March, April, and May. Convective QBWO is traced by the 10–20-day OLR. In this study, the QBWO intensity is represented by standard deviations of the 10–20-day variables in spring (Teng and Wang, 2003; Wang et al., 2018). For better comparison with previous studies (Wu and Song, 2018), the QBWO intensity of kinetic energy is defined as the averaged kinetic energy in spring, calculated by using the 10–20-day zonal and meridional winds.

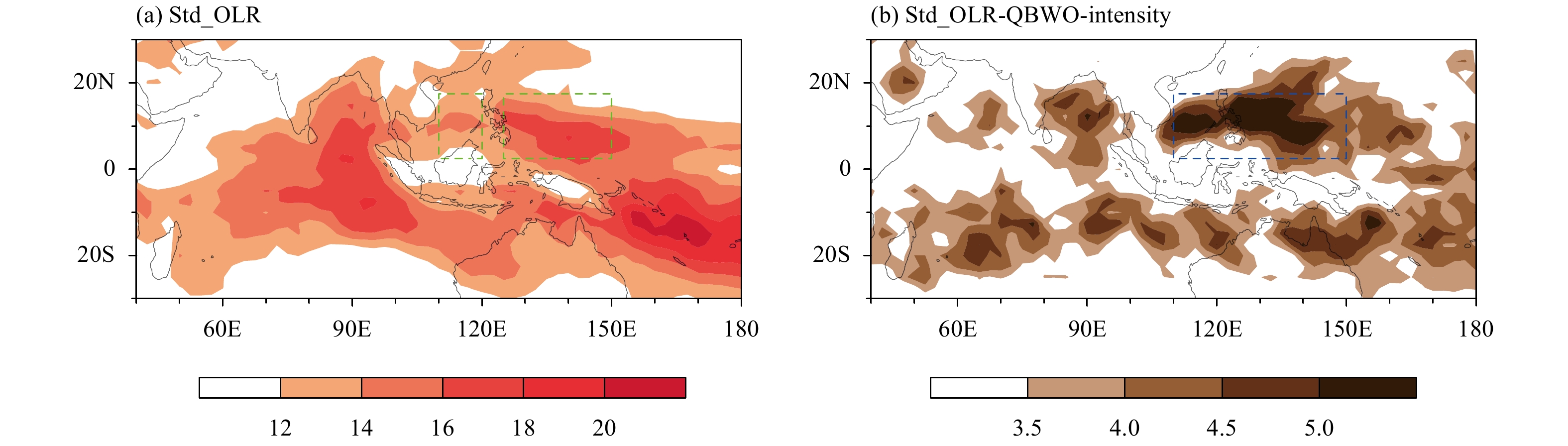

3 Characteristics of convective QBWO over the SCS and WNP in springAs indicated by standard deviations of the 10–20-day OLR (Fig. 1a), there are three convective QBWO activity centers over the tropical Indian Ocean to western Pacific in spring: the eastern tropical Indian Ocean, the SCS–WNP, and the South Pacific convergence zone. Although convective QBWO activities over the three centers are comparable, the variability of convective QBWO intensity over the SCS and WNP is much stronger than that over the other two centers (Fig. 1b). Actually, the variability of convective QBWO intensity over the SCS–WNP region is the strongest in the tropics in spring (figure omitted). To further demonstrate the significant convective QBWO activity over the SCS and WNP, spectral analysis is separately applied to the area-averaged daily OLR anomalies over a boxed region of the WNP (2.5°–17.5°N, 125.0°–150.0°E; the large green rectangle in Fig. 1a) and the SCS (2.5°–17.5°N, 110.0°–120.0°E; the small green rectangle in Fig. 1a). The 5-day running averaged OLR over the two boxes is basically less than 270 W m–2. Its climatology and standard deviation over the WNP (SCS) box are about 245.0 (246.0) and 17.0 (21.0) W m–2, respectively. Based on the monthly OLR, Waliser et al. (1993) revealed that the value of 260 or 270 W m–2 for OLR can be used as the threshold to distinguish the convective from non-convective regions in the tropics. Therefore, OLR can be used to trace the convection in the two boxes. For the WNP box, there is a peak of the multiyear mean power spectra above the 0.05 significance level in the 10–20-day period (Fig. 2a). As for the power spectra of individual years, 30 of 36 yr shows peaks above the 0.05 significance level in the 10–20-day period (figure omitted). For the SCS box, the multiyear mean power spectra are also significant at the 0.05 level in the 10–20-day period (Fig. 2b). Although there is no peak for the multiyear mean power spectra in the 10–20-day period, for the power spectra of individual years, 33 of 36 yr shows peaks above the 0.05 significance level in this period (figure omitted). Therefore, there is significant convective QBWO over the SCS–WNP region in spring.

|

| Figure 1 Standard deviations of (a) 10–20-day OLR (W m–2) and (b) OLR QBWO intensity (W m–2) in spring of 1980–2016. The WNP box, marked by the large green rectangle, refers to the region (2.5°–17.5°N, 125.0°–150.0°E). The SCS box, marked by the small green rectangle, refers to the region (2.5°–17.5°N, 110.0°–120.0°E). The SCS–WNP box, marked by the blue rectangle, refers to the region (2.5°–17.5°N, 110.0°–150.0°E). |

|

| Figure 2 The 33-yr mean power spectra of daily OLR anomalies averaged over the (a) WNP box (large green rectangle in Fig. 1a) and (b) SCS box (small green rectangle in Fig. 1a) in spring. The Markov red-noise spectrum (green line), a priori 0.05 significance level (blue line), and a posteriori 0.05 significance level (red line) are also shown. Daily OLR anomalies in spring are smoothed by a 5-day running average before the spectral analysis is employed for each year during 1980–2016. |

To reveal the spatiotemporal evolution of convective QBWO over the SCS and WNP, the composite analysis, which is the difference between active and suppressed convective QBWO events, is carried out. As shown by Figs. 3, 5, evolution of the convective QBWO over the WNP and SCS shows differences. Therefore, active and suppressed convective QBWO events are separately selected for the WNP and SCS. The active (suppressed) convective QBWO events over the WNP are selected when the standardized 10–20-day OLR over the WNP box exceeds –1 (1) in the peak phase. The active (suppressed) convective QBWO events for the SCS are selected in a similar way, but over the SCS box.

|

| Figure 3 Composite evolution of 10–20-day OLR (shaded; W m–2) and 850-hPa wind (vectors; m s–1) for convective QBWO over the WNP in spring. The plotted fields are significant at the 0.05 significance level. Day 0 indicates the reference time when the 10–20-day OLR over the WNP box is in its peak phase. |

|

| Figure 5 Composite evolution of 10–20-day OLR (shaded; W m–2) and 850-hPa wind (vector; m s–1) for convective QBWO over the SCS in spring. The plotted fields are significant at the 0.05 significance level. Day 0 indicates the reference time when the 10–20-day OLR over the SCS box is in its peak phase. |

According to Fig. 3, for convective QBWO over the WNP, an anomalous cyclonic circulation appears southeast of the Philippines Sea (5.0°N, 150.0°E) on Day –6. From Days –4 to 0, the anomalous cyclonic circulation and enhanced convection develop and propagate northwestward. The enhanced convection reaches its peak over the WNP box on Day 0. The perturbations weaken as they continue to propagate northwestward. The verti-cal motion and specific humidity over the WNP box exhibit a deep vertical structure in the troposphere (Figs. 4a, b), but the vertical relative vorticity is out-of-phase between the lower and upper troposphere (Fig. 4c). Centers of the vertical motion and specific humidity are located within 300–400 and 850–500 hPa, respectively (Figs. 4a, b).

|

| Figure 4 Composite vertical–time cross-sections of 10–20-day variables over the WNP box for convective QBWO over the WNP in spring. (a) vertical motion (Omega; 10–2 Pa s–1), (b) specific humidity (Shum; g kg–1), and (c) vertical relative vorticity (Vvort; 10–5 s–1). Shading indicates the 0.05 significance level. Day 0 indicates the reference time when the 10–20-day OLR over the WNP box is in its peak phase. |

As shown in Fig. 5, for convective QBWO over the SCS, there is an anomalous cyclonic circulation east of the Philippines on Day –6. From Days –4 to 0, the initial perturbations (the anomalous cyclonic circulation and enhanced convection) develop when propagating westward. On Day 0, the enhanced convection reaches its peak phase over the SCS box. The perturbations weaken as they continue to propagate westward. Over the SCS box, the vertical motion and specific humidity also exhibit a deep vertical structure in the troposphere, and the verti-cal relative vorticity is out-of-phase between the lower and upper troposphere (Fig. 6).

|

| Figure 6 As in Fig. 3, but for the SCS box for convective QBWO over the SCS in spring. (a) vertical motion (Omega; 10–2 Pa s–1), (b) specific humidity (Shum; g kg–1), and (c) vertical relative vorticity (Vvort; 10–5 s–1). Shading indicates the 0.05 significance level. Day 0 indicates the reference time when the 10–20-day OLR over the SCS box is in its peak phase. |

As revealed above, the convective QBWO over the WNP and SCS in spring shows westward or northwestward propagation features, which indicates that it is closely connected to equatorial Rossby waves. Similar to Chen and Sui (2010), the zonal wavelength and phase speed of the convective QBWO over the WNP and SCS in spring are calculated, separately. The zonal wave-length is about 7000 (6000) km and the phase speed is –5.79 (–4.96) m s–1 over the WNP (SCS). Furthermore, during the evolution of convective QBWO over the WNP and SCS, in addition to the anomalous cyclone at 850 hPa over the WNP–SCS (Figs. 3, 5), there is an anomalous cyclone along the same longitudinal band in the counterpart region of the Southern Hemisphere (figure omitted). These features are consistent with characteristics of n = 1 equatorial Rossby waves. Therefore, the westward or northwestward propagating convective QBWO over the WNP and SCS in spring is probably connected to n = 1 equatorial Rossby waves.

4 Interannual variation of convective QBWO intensity over the SCS–WNP region in springIn this section, the interannual variation of convective QBWO intensity over the SCS–WNP region in spring is investigated. Linear trends of variables are removed to extract interannual signals. Empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis is applied to the convective QBWO intensity anomalies over the SCS–WNP region to reveal the dominant mode of their variation. The dominant mode (EOF1), which is independent of other EOF modes based on the criteria of North et al. (1982), accounts for 30.3% of the total variance. The anomalies in EOF1 are almost in-phase, with the center located east of the Philippines (Fig. 7a). Therefore, EOF1 is a homogeneous mode. Based on EOF1, an index of the convective QBWO intensity is defined as the standardized area-averaged convective QBWO intensity over the SCS–WNP box (5.0°–17.5°N, 110°–150°E) in spring. The correlation coefficient between the index and time coefficients of EOF1 (Fig. 7b) is 0.99. Therefore, the index is used to describe the interannual variation of EOF1. When the index is greater (less) than 0.0, EOF1 is in a positive (negative) phase. That is, there is enhanced (weakened) convective QBWO intensity over the SCS–WNP region in spring.

|

| Figure 7 (a) Dominant mode and (b) its standardized time coefficients of EOF analysis of convective QBWO intensity anomalies over the SCS–WNP box in spring during 1980–2016. The dominant mode accounts for 30.3% of the total variance. |

Figure 8 presents the regressed QBWO intensities of various atmospheric variables against the index over the SCS–WNP region in spring. Corresponding to the positive phase of EOF1, the local QBWO intensity of vertical motion is enhanced throughout the troposphere over the SCS–WNP box, with a maximum at the middle level (Figs. 8a, e). Meanwhile, the local QBWO intensity of specific humidity is enhanced above 700 hPa, with a maximum at 500 hPa, but weakened slightly below 700 hPa (Figs. 8b, f). Furthermore, the local QBWO intensities of vertical vorticity and kinetic energy are enhanced (weakened) in the lower (upper) troposphere over the SCS–WNP box (Figs. 8c, d, g, h). Similar features are also found for QBWO intensities of the zonal and meridional winds (figure omitted).

|

| Figure 8 Regressed spring QBWO intensities of (a, b) 500-hPa vertical motion (Omega; 10–2 Pa s–1) and specific humidity (Shum; g kg–1), and (c, d) 850-hPa vertical relative vorticity (Vvort; 10–5 s–1) and kinetic energy (KE; m2 s–2) against the convective QBWO intensity index during 1980–2016. (e–h) As in (a–d), but for vertical profiles of regressed QBWO intensities over the SCS–WNP box. Dashed and solid lines in (a–d) indicate the 0.10 and 0.05 significance level, respectively; and blue and red dots in (e–h) indicate the same. |

As shown by Fig. 9, increase in the background moisture over the SCS–WNP region in spring provides more moisture for the 10–20-day convection, and hence favoring the positive phase of EOF1. Corresponding to the positive phase of EOF1, the maximum increase in background moisture over the SCS–WNP box is located within 850–700 hPa (Fig. 9b). The local anomalous background easterly vertical shear also favors the positive phase of EOF1 (Fig. 10). Convective QBWO over the SCS–WNP region in spring is probably connected to n = 1 equatorial Rossby waves. As revealed by previous studies (Wang and Xie, 1996; Xie and Wang, 1996), the anomalous background easterly vertical shear favors the trapping of equatorial Rossby waves at the lower level. As a result, equatorial Rossby waves are enhanced (weakened) at the lower (upper) level. The enhanced waves at the lower level may lead to enhanced 10–20-day convection by generating stronger Ekman pumping–induced heating. Therefore, the anomalous background easterly vertical shear over the SCS–WNP region in spring favors an enhanced convective QBWO intensity, i.e., the positive phase of EOF1.

|

| Figure 9 (a) Regressed 700-hPa background specific humidity (g kg–1) and (b) vertical profile of regressed background specific humidity (g kg–1) over the SCS–WNP box in spring against the convective QBWO intensity index during 1980–2016. Black dots in (a) indicate the 0.05 significance level. Red dots in (b) indicate the 0.05 significance level. |

|

| Figure 10 Regressed background zonal wind vertical shear (200 hPa minus 850 hPa; m s–1) in spring against the convective QBWO intensity index during 1980–2016. Black dots indicate the 0.05 significance level. |

The anomalous background easterly vertical shear favors enhanced (weakened) equatorial Rossby waves at the lower (upper) level. This contributes to the fact that the positive phase of EOF1 is accompanied by local enhanced (weakened) QBWO intensities of the vertical relative vorticity, kinetic energy, as well as zonal and meridional winds in the lower (upper) troposphere. To confirm this, a background zonal wind vertical shear index is defined as the standardized area-averaged background zonal wind vertical shear over the SCS–WNP box in spring. Figure 11 shows the regressed QBWO intensities of various variables over the SCS–WNP box against the convective QBWO intensity index, with the signal of the background zonal wind vertical shear index being first removed by linear regression. As shown in Fig. 11, without the influence of the anomalous background zo-nal wind vertical shear over the SCS–WNP region, the relationship between EOF1 and local QBWO intensities of the vertical motion and specific humidity changes slightly (cf. Figs. 8e, f and 11a, b). However, the relationship between EOF1 and local QBWO intensities of the vertical relative vorticity (cf. Figs. 8g and 11c), kinetic energy (cf. Figs. 8h and 9d), as well as zonal and meridional winds (figure omitted) changes remarkably. Corresponding to the positive phase of EOF1, local QBWO intensities of the four variables are enhanced throughout the troposphere.

|

| Figure 11 Vertical profiles of regressed spring QBWO intensities over the SCS–WNP box of (a) vertical motion (Omega; 10–2 Pa s–1), (b) specific humidity (Shum; g kg–1), (c) vertical relative vorticity (Vvort; 10–5 s–1), and (d) kinetic energy (KE; m2 s–2) against the convective QBWO intensity index during 1980–2016, with the signal of background zonal wind vertical shear over the SCS–WNP being first removed in the linear regression. Blue and red dots indicate the 0.10 and 0.05 significance level, respectively. |

The convective QBWO intensity index is significantly and negatively correlated with background SST anomalies in the equatorial central and eastern Pacific in the preceding winter to summer (Figs. 12a–c), but insignificantly correlated to those from autumn to the following winter (Figs. 12d, e). This indicates that EOF1 is mainly influenced by the preceding ENSO, but probably has no connection to the development of ENSO. A simi-lar relationship between the QBWO intensity of 850-hPa kinetic energy and ENSO was revealed by Wu (2018). Background atmospheric fields over the SCS–WNP region in spring can be influenced by the preceding ENSO, for example, as revealed by Wang et al. (2000) and Yuan and Yang (2012). Therefore, EOF1 can be modulated by background SST anomalies in the equatorial central and eastern Pacific in the preceding winter, as demonstrated below.

|

| Figure 12 Regressed background SST (°C) in the preceding winter to following winter against the convective QBWO intensity index during 1980–2016. (a) Preceding winter, (b) spring, (c) summer, (d) autumn, and (e) winter. Black dots indicate the 0.05 significance level. |

When EOF1 is in its positive phase, La Niña-like SST anomalies appear in the tropical Pacific in the preceding winter and spring (Figs. 12a, b). Accordingly, there are increased (decreased) precipitation over the SCS–WNP region, Maritime Continent, and South Pacific convergence zone (equatorial central and eastern Pacific) (figure omitted), and enhanced Walker circulations over the tropical Indian Ocean and Pacific in spring (Fig. 13). Corresponding to the enhanced Walker circulation in the Indian Ocean, anomalous westerlies (easterlies) prevail in the lower (upper) troposphere over the tropical Indian Ocean to WNP (Fig. 13). Therefore, the anomalous background easterly vertical shear appears over the SCS–WNP region (Fig. 12). Furthermore, the increased precipitation over the SCS–WNP region, which is caused by the local air–sea interaction and remote effects from the colder SST in the equatorial central and eastern Pacific (Zhang et al., 1996; Wang et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2017), induces a Rossby-wave response with an anomalous cyclone (anticyclone) in the lower (upper) troposphere to its northwest (Fig. 13). This also contributes to the anomalous background easterly vertical shear over the SCS–WNP region. Besides, corresponding to the increased precipitation, anomalous ascent dominates in the troposphere and anomalous horizontal convergence dominates in the lower troposphere over the SCS–WNP region. Therefore, moisture in the lower troposphere increases (Fig. 10). Influenced by the increased background moisture and anomalous background easterly vertical shear, EOF1 tends to be in its positive phase.

|

| Figure 13 Regressed background (a) 850- and (b) 200-hPa wind (m s–1) in spring against the convective QBWO intensity index during 1980–2016. Light and dark shadings indicate the 0.10 and 0.05 significance level, respectively. |

An interesting question is: without the influence of background SST anomalies in the equatorial central and eastern Pacific in the preceding winter, is the dominant mode still homogeneous and what is its relationship with background SST anomalies? EOF analysis is applied to the convective QBWO intensity anomalies over the SCS–WNP in spring after removing the signal of Niño3.4 index in the preceding winter by linear regression. As shown in Fig. 14a, the dominant mode (termed RE-EOF1) is still a homogeneous mode, and independent of other modes, but its anomalies over the SCS decrease remarkably and the explained variance drops to 20.1%. The convective QBWO intensity index, with the Niño3.4 index signal in the preceding winter removed, is used to represent the interannual variation of RE-EOF1. This is because the correlation coefficient between the convective QBWO intensity index and time coefficients of RE-EOF1 (Fig. 14b) is 0.89. The index is insignificantly correlated with background SST anomalies in the equatorial central and eastern Pacific in the preceding winter (Fig. 15a). It is, however, significantly and positively (negatively) correlated to background SST anomalies in the tropical WNP (equatorial eastern Pacific) in spring (Fig. 15b). SST anomalies in these two regions may lead to the anomalous Walker circulation in the tropical Indian Ocean and anomalous precipitation in the tropical WNP (figure omitted), which results in anomalous background atmospheric fields as described above modulating the interannual variation of RE-EOF1. The pattern of background SST anomalies persists to summer and disappears in autumn (Figs. 15c, d).

|

| Figure 14 (a) Dominant mode and (b) its standardized time coefficients of EOF analysis of convective QBWO intensity anomalies over the SCS–WNP region in spring during 1980–2016, with the signal of Niño3.4 index in the preceding winter being first removed. The dominant mode accounts for 20.1% of the total variance. |

|

| Figure 15 Regressed background SST (°C) against the convective QBWO intensity index during 1980–2016, with the signal of the Niño3.4 index in the preceding winter being first removed. (a) Preceding winter, (b) spring, (c) summer, and (d) autumn. Black dots indicate the 0.05 significance level. |

In spring, there are three convective QBWO activity centers over the tropical Indian Ocean to western Pacific: the eastern tropical Indian Ocean, the SCS–WNP, and the South Pacific convergence zone. As indicated by spectral analysis, the convection exhibits significant QBWO over the SCS–WNP region in spring. Convective QBWO over the WNP and SCS shows similarities and differences. Convective QBWO over the WNP usually originates from southeast of the Philippines Sea and moves northwestward. In contrast, convective QBWO over the SCS can usually be traced to east of the Philippines and propagates westward. The westward or northwestward propagation is probably connected to n = 1 equatorial Rossby waves. During the evolution of convective QBWO over the WNP and SCS, the vertical motion and specific humidity exhibit a barotropic structure, and vertical relative vorticity shows a baroclinic structure in the troposphere.

The dominant mode of interannual variation of the convective QBWO intensity over the SCS–WNP region in spring is homogeneous, with an anomalous center located east of the Philippines. It accounts for 30.3% of the total variance. The positive phase of the mode, which indicates enhanced the convective QBWO intensity over the SCS–WNP region in spring, is accompanied by the local enhanced QBWO intensity of vertical motion throughout the troposphere, with the center located at the middle level. Moreover, it is also connected to the local enhanced (slightly weakened) QBWO intensity of specific humidity above (below) 700 hPa. Meanwhile, it is also accompanied by local enhanced (weakened) QBWO intensities of the vertical relative vorticity, kinetic energy, as well as zonal and meridional winds in the lower (upper) troposphere. On the interannual timescale, both the local increased background moisture and anomalous background easterly vertical shear tend to favor the positive phase of the dominant mode. Furthermore, the local anomalous background easterly vertical shear is probably a factor contributing to the relationship between the dominant mode and QBWO intensities of the four variables in the troposphere. Sea surface temperature cooling in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific in the preceding winter can lead to the increased background moisture and anomalous background easterly vertical shear over the SCS–WNP region in spring, hence favoring the positive phase of the dominant mode. There is no significant relationship between the dominant mode and background SST anomalies in the following winter.

Without the influence of background SST anomalies in the equatorial central and eastern Pacific in the preceding winter, the dominant mode of interannual variation of the convective QBWO intensity over the SCS–WNP region in spring is still a homogeneous mode, but the explained variance decreases to 20.1% and its anomalies over the SCS decrease remarkably. Corresponding to the positive phase of this mode, there is sea surface warming (cooling) in the tropical WNP (equatorial eastern Pacific) in spring, which modulates background atmospheric fields over the SCS–WNP region. Such a pattern of background SST anomalies persists to summer and disappears in autumn.

| Adler, R. F., G. J. Huffman, A. Chang, et al., 2003: The version-2 global precipitation climatology project (GPCP) monthly precipitation analysis (1979–present). J. Hydrometeorol., 4, 1147–1167. DOI:10.1175/1525-7541(2003)004<1147:TVGPCP>2.0.CO;2 |

| Chatterjee, P., and B. N. Goswami, 2004: Structure, genesis and scale selection of the tropical quasi-biweekly mode. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 130, 1171–1194. DOI:10.1256/qj.03.133 |

| Chen, G. H., and C. H. Sui, 2010: Characteristics and origin of quasi-biweekly oscillation over the western North Pacific during boreal summer. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 115, D14113. DOI:10.1029/2009jd013389 |

| Chen, G. H., and X. Wang, 2017: Effect of the westward-propagating zonal wind anomaly on the initial development of quasi-biweekly oscillation over the South China Sea during early summer. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett., 10, 89–95. DOI:10.1080/16742834.2017.1243002 |

| Chen, J. P., Z. P. Wen, R. G. Wu, et al., 2015: Influences of northward propagating 25–90-day and quasi-biweekly oscillations on eastern China summer rainfall. Climate Dyn., 45, 105–124. DOI:10.1007/s00382-014-2334-y |

| Chen, T. C., and J. M. Chen, 1995: An observational study of the South China Sea monsoon during the 1979 summer: Onset and life cycle. Mon. Wea. Rev., 123, 2295–2318. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1995)123<2295:AOSOTS>2.0.CO;2 |

| Chen, X., J. Ling, and C. Y. Li, 2016: Evolution of the Madden–Julian oscillation in two types of El Niño. J. Climate, 29, 1919–1934. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-15-0486.1 |

| Dee, D. P., S. M. Uppala, A. J. Simmons, et al., 2011: The ERA-Interim reanalysis: Configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 137, 553–597. DOI:10.1002/qj.828 |

| Duchon, C. E., 1979: Lanczos filtering in one and two dimensions. J. Appl. Meteor., 18, 1016–1022. DOI:10.1175/1520-0450(1979)018<1016:LFIOAT>2.0.CO;2 |

| Fukutomi, Y., and T. Yasunari, 1999: 10–25 day intraseasonal variations of convection and circulation over East Asia and western North Pacific during early summer. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan, 77, 753–769. DOI:10.2151/jmsj1965.77.3_753 |

| Gushchina, D., and B. Dewitte, 2012: Intraseasonal tropical atmospheric variability associated with the two flavors of El Niño. Mon. Wea. Rev., 140, 3669–3681. DOI:10.1175/MWR-D-11-00267.1 |

| Hsu, P. C., T. H. Lee, C. H. Tsou, et al., 2017: Role of scale interactions in the abrupt change of tropical cyclone in autumn over the western North Pacific. Climate Dyn., 49, 3175–3192. DOI:10.1007/s00382-016-3504-x |

| Jia, X. L., and S. Yang, 2013: Impact of the quasi-biweekly oscillation over the western North Pacific on East Asian subtropi-cal monsoon during early summer. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 118, 4421–4434. DOI:10.1002/jgrd.50422 |

| Kikuchi, K., and B. Wang, 2009: Global perspective of the quasi-biweekly oscillation. J. Climate, 22, 1340–1359. DOI:10.1175/2008JCLI2368.1 |

| Li, C. H., T. Li, A. L. Lin, et al., 2015: Relationship between summer rainfall anomalies and sub-seasonal oscillations in South China. Climate Dyn., 44, 423–439. DOI:10.1007/s00382-014-2172-y |

| Li, R. C. Y., and W. Zhou, 2013: Modulation of western North Pacific tropical cyclone activity by the ISO. Part I: Genesis and intensity. J. Climate, 26, 2904–2918. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00210.1 |

| Li, T., and B. Wang, 2005: A review on the western North Pacific monsoon: Synoptic-to-interannual variabilities. Terrestrial, Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, 16, 285–314. DOI:10.3319/TAO.2005.16.2.285(A) |

| Liebmann, B., and C. A. Smith, 1996: Description of a complete (interpolated) outgoing longwave radiation dataset. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 77, 1275–1277. DOI:10.1175/1520-0477-77.6.1274 |

| Lin, A. L., and T. Li, 2008: Energy spectrum characteristics of boreal summer intraseasonal oscillations: Climatology and variations during the ENSO developing and decaying phases. J. Climate, 21, 6304–6320. DOI:10.1175/2008JCLI2331.1 |

| Mao, J. Y., and J. C. L. Chan, 2005: Intraseasonal variability of the South China Sea summer monsoon. J. Climate, 18, 2388–2402. DOI:10.1175/JCLI3395.1 |

| North, G. R., T. L. Bell, R. F. Cahalan, et al., 1982: Sampling errors in the estimation of empirical orthogonal functions. Mon. Wea. Rev., 110, 699–706. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1982)110<0699:SEITEO>2.0.CO;2 |

| Ren, X. J., X. Q. Yang, and X. G. Sun, 2013: Zonal oscillation of western Pacific subtropical high and subseasonal SST variations during Yangtze persistent heavy rainfall events. J. Climate, 26, 8929–8946. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00861.1 |

| Smith, T. M., R. W. Reynolds, T. C. Peterson, et al., 2008: Improvements to NOAA’s historical merged land–ocean surface temperature analysis (1880–2006). J. Climate, 21, 2283–2296. DOI:10.1175/2007JCLI2100.1 |

| Teng, H. Y., and B. Wang, 2003: Interannual variations of the boreal summer intraseasonal oscillation in the Asian–Pacific region. J. Climate, 16, 3572–3584. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(2003)016<3572:IVOTBS>2.0.CO;2 |

| Waliser, D. E., N. E. Graham, and C. Gautier, 1993: Comparison of the highly reflective cloud and outgoing longwave radiation datasets for use in estimating tropical deep convection. J. Climate, 6, 331–353. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(1993)006<0331:cothrc>2.0.co;2 |

| Wang, B., and X. S. Xie, 1996: Low-frequency equatorial waves in vertically sheared zonal flow. Part I: Stable waves. J. Atmos. Sci., 53, 449–467. DOI:10.1175/1520-0469(1996)053<0449:LFEWIV>2.0.CO;2 |

| Wang, B., R. G. Wu, and X. H. Fu, 2000: Pacific–East Asian teleconnection: How does ENSO affect East Asian climate?. J. Climate, 13, 1517–1536. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(2000)013<1517:PEATHD>2.0.CO;2 |

| Wang, L., T. Li, L. Chen, et al., 2018: Modulation of the MJO intensity over the equatorial western Pacific by two types of El Niño. Climate Dyn., 51, 687–700. DOI:10.1007/s00382-017-3949-6 |

| Wen, M., and R. H. Zhang, 2008: Quasi-biweekly oscillation of the convection around Sumatra and low-level tropical circulation in boreal spring. Mon. Wea. Rev., 136, 189–205. DOI:10.1175/2007MWR1991.1 |

| Wen, M., T. Li, R. H. Zhang, et al., 2010: Structure and origin of the quasi-biweekly oscillation over the tropical Indian Ocean in boreal spring. J. Atmos. Sci., 67, 1965–1982. DOI:10.1175/2009JAS3105.1 |

| Wu, B., T. J. Zhou, and T. Li, 2017: Atmospheric dynamic and thermodynamic processes driving the western North Pacific anomalous anticyclone during El Niño. Part II: Formation processes. J. Climate, 30, 9637–9650. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0495.1 |

| Wu, R. G., 2018: Feedback of 10–20-day intraseasonal oscillations on seasonal mean SST in the tropical western North Pacific during boreal spring through fall. Climate Dyn., 51, 4169–4184. DOI:10.1007/s00382-016-3362-6 |

| Wu, R. G., and X. Cao, 2017: Relationship of boreal summer 10–20-day and 30–60-day intraseasonal oscillation intensity over the tropical western North Pacific to tropical Indo-Pacific SST. Climate Dyn., 48, 3529–3546. DOI:10.1007/s00382-016-3282-5 |

| Wu, R. G., and L. Song, 2018: Spatiotemporal change of intraseasonal oscillation intensity over the tropical Indo-Pacific Ocean associated with El Niño and La Niña events. Climate Dyn., 50, 1221–1242. DOI:10.1007/s00382-017-3675-0 |

| Xie, X. S., and B. Wang, 1996: Low-frequency equatorial waves in vertically sheared zonal flow. Part II: Unstable waves. J. Atmos. Sci., 53, 3589–3605. DOI:10.1175/1520-0469(1996)053<3589:LFEWIV>2.0.CO;2 |

| Xu, Z. Q., T. Li, and K. Fan, 2017: The weakened intensity of the atmospheric quasi-biweekly oscillation over the western North Pacific during late summer around the late 1990s. J. Climate, 30, 9807–9826. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0759.1 |

| Yang, J., B. Wang, and B. Wang, 2008: Anticorrelated intensity change of the quasi-biweekly and 30–50-day oscillations over the South China Sea. Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, L16702. DOI:10.1029/2008GL034449 |

| Yuan, Y., and S. Yang, 2012: Impacts of different types of El Niño on the East Asian climate: Focus on ENSO cycles. J. Climate, 25, 7702–7722. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00576.1 |

| Yuan, Y., C. Y. Li, and J. Ling, 2015: Different MJO activities between EP El Niño and CP El Niño. Scientia Sinica Terrae, 45, 318–334. DOI:10.1360/zd-2015-45-3-318 |

| Zhang, R. H., A. Sumi, and M. Kimoto, 1996: Impact of El Niño on the East Asian monsoon: A diagnostic study of the ’86/87 and ’91/92 events. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan, 74, 49–62. DOI:10.2151/jmsj1965.74.1_49 |

| Zhou, W., and J. C. L. Chan, 2005: Intraseasonal oscillations and the South China Sea summer monsoon onset. Int. J. Climatol., 25, 1585–1609. DOI:10.1002/joc.1209 |

| Zveryaev, I. I., 2002: Interdecadal changes in the zonal wind and the intensity of intraseasonal oscillations during boreal summer Asian monsoon. Tellus A, 54, 288–298. DOI:10.1034/j.1600-0870.2002.00235.x |

2019, Vol. 33

2019, Vol. 33