The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- Bingyun WANG, Ming WEI, Wei HUA, Yongli ZHANG, Xiaohang WEN, Jiafeng ZHENG, Nan LI, Han LI, Yu WU, Jie ZHU, Mingjun ZHANG. 2017.

- Characteristics and Possible Formation Mechanisms of Severe Storms in the Outer Rainbands of Typhoon Mujigae (1522). 2017.

- J. Meteor. Res., 31(3): 612-624

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-017-6043-4

Article History

- Received April 22, 2016

- in final form October 10, 2016

2. College of Atmospheric Sciences, Chengdu University of Information Technology/Plateau Atmosphere and Environment Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, Chengdu 610225;

3. Hainan Meteorological Observatory, Haikou 570203;

4. National Satellite Meteorological Center, Beijing 100081

A strong typhoon, named Mujigae, occurred during 2–5 October 2015. Its outer spiral rainbands contained multiple severe storm cells, which resulted in severe weather events, mesocyclones, and tornadoes that caused a considerable number of casualties and substantial economic losses. Generally, the strongest winds, heaviest rains, and deep convective thunderstorms of typhoons are found in the eye wall, making it the most dangerous part. However, major disasters often occur in the outer spiral rainbands of typhoons, far from the eye and eyewall (inner core), due to severe storms, mesocyclones, and tornadoes. Why this happens is an important question. Convective and stratiform clouds constitute the cloud types in the spiral rainbands of a typhoon, and most of the clouds in the updraft region are convective. The development and intensity of such convection reflect the mass and energy changes in the typhoon’s rainbands (Shou et al., 2003; Chen, 2010). Previous studies have found that Doppler radar velocity data can be use to distinguish mesoscale cyclones (called tornado parent clouds when a tornado occurs, 20–50 km in diameter), tornado vortices [referred to as the TVS (tornado vortex signature, 2–4 km in diameter], and tornadoes (sometimes occurring in the TVS, tens to hundreds of meters in diameter) in the evolution of severe storms (Yu et al., 2006). The storm cells include mesocyclones with high rotational speed, strong azimuthal shear speed, long maintenance time, and deep vertical stretch. These mesocyclones can cause meteorological disasters and economic losses that are more severe compared to those caused by general convective storms.

Many researchers have studied and analyzed the weather systems in outer rainbands of typhoons (or hurricanes), including severe storms, mesoscale cyclones, and tornado vortices. In terms of dynamic and thermodynamic mechanisms, the mesocyclone vortices and tornadic cells can intensify just before the typhoon’s landfall and induce tornadoes along the coast in the outer rainbands, demonstrating the ability of baroclinic boundaries to enhance low-level horizontal vorticity and to subsequently intensify the updraft rotation within passing cells. However, the tornadic cells weaken rapidly when the typhoon moves a little farther inland, indicating the presence of a narrow coastal zone in which both the wind shear and buoyancy are favorable for tornado genesis (Benjamin et al., 2011; Todd and Knupp, 2013). Statistical analysis of radar data has indicated that the products of radar observations, such as velocity and reflectivity, can be used successfully to monitor and estimate strong echoes, mesocyclones, convective cells, squall lines, wind shear, short-term strong precipitation, hail, and gales (Wu et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2005; Fang and Zheng, 2007; Feng et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2010, 2015; Zhou, 2010; Zhang et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2012), as well as help to analyze the structure, strength, dynamics, and thermal evolutionary mechanisms for the above systems. Furthermore, they can provide corresponding indicators to guide short-term nowcasting work (Zhao et al., 2007; Matthew and Link, 2009; Matthew and Fuelberg, 2014). With the development of numerical models, numerical simulations have been used to analyze the dynamic, thermodynamic, and structural evolution mechanisms for typhoons (Glen and Wilhelmson, 2006; Wang and Ding, 2008; Ding et al., 2009), including the mechanisms for rain formation and evolution and cyclone formation, and the effect of topography (Franklin et al., 2006; Daniel et al., 2007; Li and Wang, 2012).

The majority of previous studies have focused on typhoons that occurred in summer or spring. In contrast, there have been few studies of strong disaster-causing typhoons that occurred in autumn, especially those that made landfall over mainland China. The NCEP reanalysis data, conventional meteorological data, and the Chinese New Generation Weather Radar of S-band type A (short for CINRAD/SA) Doppler radar data for the period when Typhoon Mujigae—a strong typhoon—made landfall in Guangdong Province, China, were used in this study. The rainbands and severe storm cells were examined to obtain the characteristics of severe storms, mesoscale cyclones, and tornado vortices in the outer rainbands that occurred in Shanwei and Guangzhou. The results of the present study could promote a deeper understanding of severe weather evolution and possible formation mechanisms of storms occurring far away from the inner core of typhoons, as well as help to prevent or reduce disasters caused by typhoons.

2 Background of Typhoon Mujigae2.1 DataThe NCEP–NCAR reanalysis data used in this study were from the NCEP–NCAR Reanalysis-1 project, generated from a state-of-the-art analysis/forecast system that performs data assimilation using past data from 1948 to the present day. The dataset includes four-time daily, daily, and monthly data for the period from 1 January 1948 to the present day, and long-term monthly means derived from the reanalysis data for the years 1981–2010. In terms of spatial coverage, it is a global gridded dataset with 17 pressure levels and 28 sigma levels in the vertical direction. The dataset is updated on a daily basis. In this study, Reanalysis-1 data at 0000, 0600, 1200, and 1800 UTC and at 0800, 1400, 2000, and 0200 (day + 1) Beijing Time (BT) during 1–5 October 2015 were used (the same for other data). Variables such as zonal wind (uwnd), meridional wind (vwnd), specific humidity (shum), geopotential height (hgt), air temperature (air), etc. were extracted from the Reanalysis-1 data for this study.

Conventional meteorological data were obtained from the National Meteorological Information Center of the China Meteorological Administration. The data included air pressure, air temperature, humidity, wind direction, wind speed, precipitation, and other basic meteorological variables from the ground to upper levels collected at weather stations.

The CINRAD/SA Doppler weather radar was used to detect the spatial distribution, intensity, spectrum width and movement speed of clouds, and precipitation. This radar has strong monitoring and early warning capabilities for convective weather, tropical cyclones, heavy rain, and other disastrous weather, with algorithms such as the storm cell identification and tracking algorithm, the mesocyclone detection algorithm, the tornado detection algorithm, the hail detection algorithm, the mesocyclone algorithm, and the velocity azimuth display algorithm. The basic products from the CINRAD/SA Doppler weather radar (15 in total) include the reflectivity factor, the radial velocity, and the spectrum width. More than 30 product types were exported, including the combination of the reflectance factor, vertical profile of reflectivity, radial velocity vertical profile, echo top, hourly accumulated rainfall, 3-h accumulated precipitation, vertical integrated liquid water (VIL), weak echo region, and velocity azimuth display wind profile. Most of these were not available in previous radar products. The CINRAD/SA Doppler radar data have two resolutions: super resolution and standard resolution. During super resolution data collection, for the split cut of each volume coverage pattern, the radar data acquisition (RDA) processes base moments with 0.5° azimuthal by 0.25-km range resolution, and the reflectivity data are processed over a range of 460 km. Standard resolution data produces base moments with 1° azimuthal by 0.25-km range resolution, and the reflectivity data are provided over a range of 460 km. In addition, the standard resolution data are produced when the super resolution data are recombined to 1° azimuthal by 0.25-km range resolution using the radar product generator, or when the super resolution is disabled at the RDA.

2.2 Meteorological conditionsAnalysis of the NCEP–NCAR reanalysis data and conventional sounding data showed that, during 2–4 October 2015, the atmospheric circulation gradually transformed from two troughs and one ridge to three troughs and two ridges at 500 hPa. The middle- and high-latitude circulation changed slowly and steadily in the Northern Hemisphere. There were some small trough and ridge perturbations above the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau. The subtropical high pressure was very strong, with the 588 pressure line maintained stably above 30°N and the subtropical high-pressure center remained over the northeastern part of the South China Sea (Fig. 1). During the propagation of Typhoon Mujigae, the subtropical high-pressure center gradually extended from southeast to northwest. As a result, the typhoon moved from southeast to northwest along the southwestern flank of the subtropical high-pressure zone (Figs. 1a–c). During the strengthening stage of Mujigae, the sea surface temperature was warmer than 28°C in the South China Sea and its adjacent region, while an obvious extreme low temperature zone with temperatures less than –80°C was located over the same region at 100 hPa. The striking differences in the temperatures between the two layers led to thermal instability (Fig. 1d). The water vapor from the Bay of Bengal and the middle of the western Pacific was sufficiently abundant for the sustainable development of the typhoon (Figs. 1a–c, blue arrow, 80 kg m–2 m s–1).

|

| Figure 1 The evolutions of the large-scale circulation at (a) 0800 BT 2 October, (b) 0800 BT 3 October, (c) 0800 BT 4 October, and (d) the distribution of meteorological elements at 0800 BT 4 October. Panels (a–c) display the ground and sea surface temperature (red shading; °C), 500-hPa height field (black lines; hPa) and wind (gray arrows; m s–1), vapor flux (blue arrows; kg m–2 m s–1), and 100-hPa temperature (red dashed lines; °C). Panel (d) presents the sea surface temperature field (red lines; °C), 925-hPa wind field (red wind barbs; m s–1), 850-hPa wind field (purple wind barbs; m s–1), 500-hPa wind field (blue wind barbs; m s–1), and 100-hPa temperature field (blue dashed lines; °C). |

Analyzing the intensity (Fig. 2a) and track (Fig. 2b) of Typhoon Mujigae can reveal its evolutionary process. At 0200 BT 2 October, a tropical depression over Luzon Island of the Philippines intensified and became a tropical storm, numbered 1522 and named Mujigae. At 2000 BT 2 October, Mujigae strengthened and became a severe tropical storm. The maximum wind speed near the inner core was 25 m s–1, the air pressure was 985 hPa, and the northwestward moving speed was 21 km h–1. After 18 h, at 1400 BT 3 October, Mujigae was located at 18.9°N, 114.3°E with intensity reaching typhoon level. The maximum wind speed near the inner core was 33 m s–1, the air pressure was 975 hPa, and the moving speed was 25 km h–1. At 2300 BT 3 October, Mujigae was located at 19.6°N, 112.8°E. The maximum wind speed near the inner core was 45 m s–1, the air pressure was 955 hPa, and the moving speed was 25 km h–1. By this time, it had evolved into a strong typhoon. After 14 h, at 1400 BT 4 October, Mujigae landed at Zhanjiang (21.0°N, 110.8°E), Guangdong Province, when it bore the intensity of a strong typhoon, with a maximum wind speed of 50 m s–1 near the inner core, air pressure of 940 hPa, and moving speed of 20 km h–1. Just 4 h later, at 1800 BT 4 October, Mujigae was located at 21.7°N, 109.8°E and it weakened from strong typhoon to typhoon, with a maximum wind speed of 38 m s–1 near the inner core, air pressure of 970 hPa, and moving speed of 20 km h–1. Another 4 h later, Mujigae continued to weaken and become a severe tropical storm. At 0300 BT 5 October, Mujigae weakened to a tropical storm.

|

| Figure 2 (a) Intensity and (b) track of Typhoon Mujigae. |

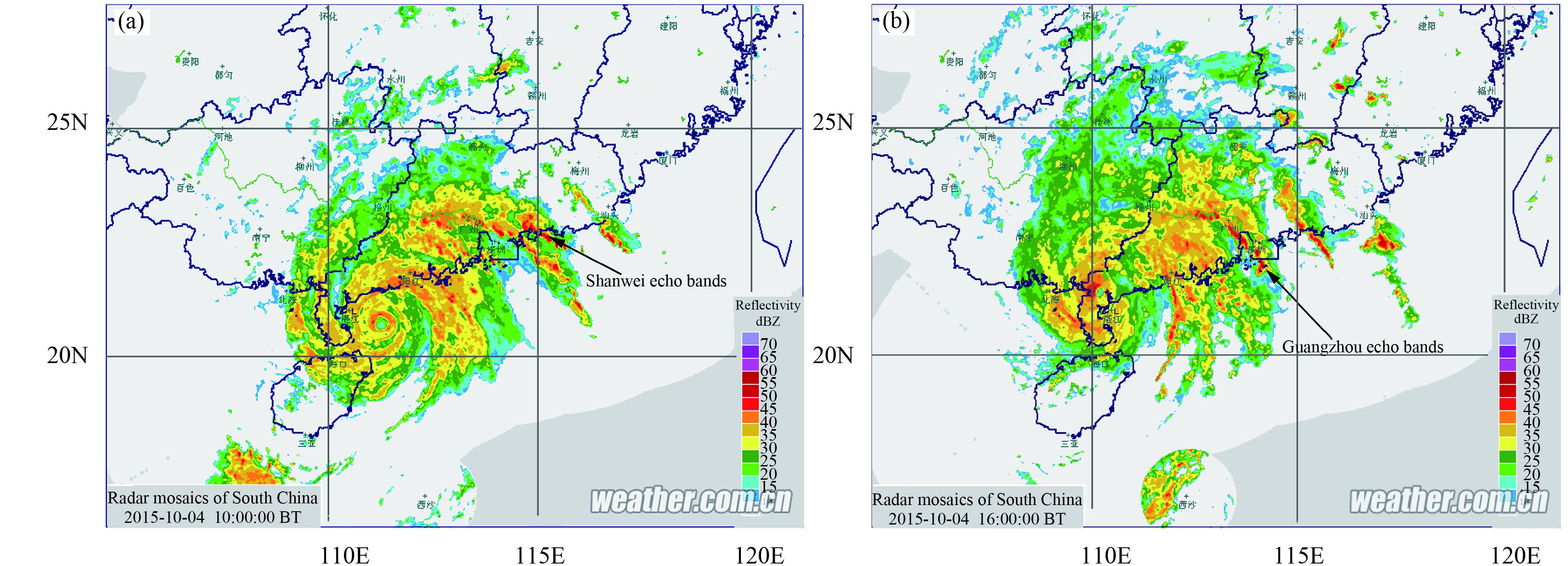

The outer rainbands of Mujigae contained multiple severe convective cells; several of them were so strong that they induced mesoscale cyclones, and a few induced tornadoes (or waterspouts). The radar mosaic for South China (Fig. 3a) shows that there were two severe echo bands with reflectivity greater than 55 dBZ to the south of Shanwei radar station; the closer one was approximately 500 km from the inner core of Mujigae. A waterspout occurred at Shanwei before the landing of Mujigae at approximately 1000 BT 4 October. The radar mosaic of South China at 1600 BT (Fig. 3b) shows strong echo bands with reflectivity greater than 55 dBZ along a line from Macao, Hong Kong, to Guangzhou, approximately 350 km from the inner core of Mujigae. Two tornadoes occurred in Guangzhou after the landfall of Mujigae at approximately 1530–1630 BT 4 October. The waterspout occurred during the strengthening stage of Mujigae before it made landfall, and the tornadoes occurred after Mujigae landed in Guangdong prior to its rapid weakening stage. All of these events took place in the northeast quadrant of Mujigae (the right-hand side of Mujigae’s trajectory), consistent with the results of McCaul (1991) and Zheng et al. (2015).

|

| Figure 3 The radar mosaics of South China at (a) 1000 BT (Beijing Time) and (b) 1600 BT 4 October 2015. |

The Doppler radar radial velocity could be used to identify mesocyclones and tornado vortices. The radar data at Shanwei and Guangzhou stations were used to identify the mesoscale cyclones from 0800 BT 3 to 0800 BT 6 October, based on the mesocyclone index (Robert and White, 1998; Williamson and Hays, 2006) and the products of the radar data inversion. The mesocyclones that occurred were confirmed, and the empty, omission, and type errors were corrected by manual modification. According to the mesocyclone algorithm, the frequencies of mesocyclone occurrence that were identified from Guangzhou and Shanwei radar data products were 387 and 127, respectively. Three types were identified: uncorrelated shear (UNC-SHR), 3D correlated shear (3DC-SHR), and mesocyclone (M). After manually comparing these results with the reflectivity, velocity, VIL, storm relative mean radial velocity map, storm track algorithm information, and other product parameters, the actual monitored frequencies of mesocyclones at the two stations were 217 and 135, respectively.

Among all the mesocyclones monitored by the two radars (Table 1), the UNC-SHR and M types accounted for nearly 95% of the total, and the 3DC-SHR type accounted for only around 5%. The average azimuth angles of the UNC-SHR and 3D-SHR types were 230° and 200° at the two radar stations, respectively. The average azimuth angle of M type mesocyclones was 250° at Guangzhou radar station and 210° at Shanwei radar station. The average distance from the UNC-SHR and 3DC-SHR mesocyclones to the radar stations was approximately 50–70 km, while the average distance between M type mesocyclones and the radar stations was approximately 42 km. Mesocyclones in different stages had different characteristics. For the UNC-SHR type, the values of average base height (BASE), top height (TOP), and shear maximum height (SHRHGT) were 1.5 km at both stations. For the 3DC-SHR type, the three parameters (BASE, TOP, and SHRHGT) at Guangzhou station were 1.8, 3, and 2.5 km, respectively, and at Shanwei station they were 1.8, 3.1, and 1.8 km, respectively. The SHRHGT at Shanwei was lower by approximately 0.7 km than that at Guangzhou. For the M type mesocyclones, the three parameters at Guangzhou station were 1.1, 2.4, and 1.7 km, respectively, and at Shanwei station they were 1.3, 2.7, and 2.1 km, respectively. The values at Shanwei were higher than those at Guangzhou by approximately 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4 km. The characteristics of the radial diameter (DIAMRAD) of the two stations were big–small–big, while those of azimuthal diameter (DIAMAZ) were small–big–small, for the three different types, respectively. The average wind shear (SHEAR) was approximately 0.01 s–1 at the two stations, and the average value for the M type mesocyclones was larger than that for the UNC-SHR and 3D-SHR types. Because the monitored frequencies of the 3DC-SHR type were too few, less than 10 at each station, the average value is not representative.

| Radar station | Number | Type | Frequency | AZ (°) | RAN (km) | BASE (km) | Middle (km) | SHRHGT (km) | DIAMRAD (km) | DIAMAZ (km) | SHEAR (10–3 s–1) |

| UNC-SHR | 66 | 228.4 | 63.0 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 4.7 | 11.1 | ||

| Guangzhou | 217 | 3DC-SHR | 8 | 206.1 | 63.3 | 1.8 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 5.8 | 9.3 |

| MESO | 143 | 254.7 | 42.5 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 12.5 | ||

| UNC-SHR | 30 | 226.8 | 51.4 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 4.9 | 8.5 | ||

| Shanwei | 135 | 3DC-SHR | 5 | 200.2 | 69.6 | 1.8 | 3.1 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 5.2 | 12.6 |

| MESO | 92 | 214.9 | 42.0 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 12.8 | ||

| Notes: The mesocyclone (M) product provides information regarding the existence and nature of vortices associated with thunderstorms. This product is generated from the output of the legacy Mesocyclone Algorithm. The product provides information regarding identified shear features within the storm. Features are classified as uncorrelated shear (sufficiently large, symmetrical, but not vertically correlated); three-dimensional shear regions (vertically correlated, but not symmetrical); and mesocyclones (sufficiently large, vertically correlated, and symmetrical). AZ, azimuth; RAN, range; BASE, base height; Middle, middle height; SHRHGT, shear maximum height; DIAMRAD, radial diameter; DIAMAZ, azimuthal diameter; SHEAR, wind shear. | |||||||||||

Mesoscale cyclones occur during severe weather events (e.g., with hail, damaging winds, and tornadoes) when severe storms exist, and 10%–15% of them are associated with tornadoes (Robert and White, 1998). During Typhoon Mujigae, the frequency of mesocyclones monitored by the two radars was 217 in Guangzhou, and 135 in Shanwei, and the accumulated warning signal product of tornadoes was more than 100. From Fig. 4a, the positions of the mesocyclones monitored by the radars in Shanwei and Guangzhou show that severe convection occurred in a zonal region approximately 100 km in length and 60 km in width to the southwest of Shanwei radar station, and in a zonal region approximately 150 km in length and 70 km in width extending from the southeast to northwest across Guangzhou radar station. The mesocyclone products monitored from 2230 BT 3 to 1900 BT 4 October in Shanwei, and from 0330 BT 4 to 1500 BT 5 October in Guangzhou, were consistent with the wind speed of the outer rainbands, which first reached a maximum in Shanwei and then in Guangzhou, accompanied by the movement of Mujigae. According to local witnesses, at least three tornadoes happened: a waterspout in Haifeng and Shanwei at approximately 1000 BT 4 October; a tornado in Shunde and Foshan during approximately 1530–1600 BT; and a tornado at Panyu (PY), Guangzhou during approximately 1600–1630 BT. Therefore, the characteristics of the evolution of the severe convective storms, mesocyclones, and tornado vortices could be analyzed. The paths of the three severe storms were from the southeast to northwest (Fig. 4b). The track of the severe storm in Shanwei that induced the waterspout at the same location (referred to as SWTVS) was the shortest, at about 80 km. It was generated within 100 km of the radar station to the southwest, and intensified to become a more powerful convective mesocyclone cell within 50 km of the radar station, where it induced SWTVS just 5–20 km away from the coastline. The severe storm at Shunde (referred to as SDSS) induced a tornado (referred to as SDTVS) at 170°, about 130 km from the radar station, and from that time, SDSS grew into a more powerful convective mesocyclone cell (referred to as SDM) within 70 km of the radar station and continued to move northwestward. SDM disappeared at 300°, 70 km from the radar station, and then SDSS weakened. The length of SDSS’s track was nearly 200 km. SDTVS was induced within 30 km of the radar station, from 200° to 270°, and caused considerable damage. Its closest distance to the radar station was approximately 20 km. The track of the severe storm in Panyu (referred to as PYSS) that induced a tornado (referred to as PYTVS) at the same location was the longest, at over 200 km, and covered an area from the southeast to northeast of the radar. A mesocyclone was induced by a convective system 60 km from the radar station in PYSS, and PYTVS was induced at 145°, 20 km away, and moved toward the radar station. The closest distance between the tornado and the radar station was 4.2 km, and the tornado resulted in large-scale blackouts in Panyu. Note that PYSS moved toward and passed through Guangzhou radar station from the northeast, and it was within the blind zone of the radar for a while when it was very close to the radar. This resulted in a loss of detection of the mesocyclone and tornado vortex. After careful analysis of the radar speed and strength, and the combination of shear and other data and the damage caused by this system, the missing information was completely recovered.

|

| Figure 4 (a) The locations of the mesocyclone products monitored in Guangzhou (GZM) and Shanwei (SWM), and (b) the tracks of severe storms (SS), mesocyclones (M), and tornadic vortices (TVS) in Panyu (PY), Shanwei (SW), and Shunde (SD) that induced tornadoes in Guangzhou and Shanwei. |

Accompanied by the movement of the outer spiral rainbands, the variables associated with severe convective cells, mesocyclones, and tornadic vortices that induced tornadoes evolved and developed. For example, during the development of severe storms, the maximum reflectivity (MAXREF) was greater than 50 dBZ and the strongest echo at Shanwei was nearly 60 dBZ (Figs. 5a1, b1, c1). The MAXREF initially increased to its maximum value when the tornado occurred, and then weakened. The height of the base of the severe storms (BASE) gradually declined and, after the tornado occurred, increased. The minimum BASE was 0.3 km in both Shanwei and Shunde, and its value was 0.1 km in Panyu, showing a strong relationship with the distance to the radar station. The top height (TOP) of the tornadoes induced by severe storms was approximately 10 km in Shanwei, 7.5 km in Shunde, and above 9 km in Panyu. When the maximum of the TOP suddenly decreased, a tornado occurred approximately 20 min later. The vertically integrated liquid water content (cell-based VIL) of the three severe storms fluctuated in their growth period prior to the formation of the tornado. When tornadoes occurred, the VIL declined sharply. The most severe storm’s VIL was greater than 40 kg m–2 in Shanwei, and approximately 30 kg m–2 in Shunde and Panyu. The maximum echo height was consistent with the changes in VIL. The BASE of the mesocyclones was higher than the convection that induced them (Figs. 5a2, b2, c2). The BASE was approximately 1 km in Shanwei, 0.5 km in Shunde, and 0.8 km in Panyu. Meanwhile, the TOP was half that of the convection that induced them. The TOP was 3 km in Shanwei and Shunde, and over 4 km in Panyu, and all TOPs were greater than the result reported in Zhou et al. (2012). The maximum wind shear in the mesocyclones (MAXSHEAR) was relatively larger when the tornadoes occurred. The MAXSHEAR was over 0.02 s–1 in Shanwei, 0.05 s–1 in Shunde, and approximately 0.02 s–1 in Panyu—values that were close to the results of Zhou et al. (2012)—and the maximum height of MAXSHEAR dropped after the tornadoes occurred. Figures 5a3, b3, and c3 show how the variables of the tornado vortices changed during the three events. The MAXSHEAR of the tornado vortex was 0.08 s–1 in Shanwei, 0.09 s–1 in Panyu, and 0.13 s–1 in Shunde.

|

| Figure 5 Evolutions of variables associated with (a1–c1) severe storms, (a2–c2) mesocyclones, and (a3–c3) tornadic vortices that induced tornadoes (or waterspouts) in (a1–a3) Shanwei, (b1–b3) Shunde, and (c1–c3) Panyu. The definitions of the variables are as follows: BASE, base height (km); TOP, top height (km); MAXREFHGT, maximum reflectivity height (km); CELL-BASED VIL, vertically integrated liquid water (kg m-2) from strom cell base; MAXREF, maximum reflectivity (dBZ); HGT, height of the maximum tangential shear (km); DIAMRAD, radial diameters (km); DIAMAZ, azimuthal diameters (km); SHEAR, maximum tangential shear (s–1); DEPTH, 3D feature depth of tornado vortex signature (km); AVGDV, average differential velocity (m s–1); LLDV, low level delta velocity (m s–1); MXDV, average differential velocity (m s–1); MXSHR, maximum tangential shear (s–1). |

From the above analysis of severe storms, mesocyclones, and tornadic vortices in the three recorded cases in the outer rainbands of Typhoon Mujigae, it can be concluded that the parent clouds experienced strengthening–weakening–strengthening changes at different stages of their life cycle, and the changes in the parent clouds had direct impacts on the intensity of the mesocyclones. Furthermore, tornadoes occurred in mesocyclones that had relatively larger values of wind shear. The magnitude of the average velocity difference and low-level velocity difference initially increased, and then decreased when the tornado occurred. However, if the parent clouds and mesocyclones were to strengthen again, the probability of tornado occurrence would increase correspondingly.

4 Possible formation mechanisms for severe storms, mesocyclones, and tornadoes in the outer spiral rainbands of a typhoonIt is well-known that a mature typhoon is nearly circular in shape, and the horizontal structure of the low-altitude wind field can be broken into three main parts: the eye, eyewall, and outer region with spiral rainbands. The nearly cloud-free area of light winds is called the eye of the typhoon and is generally 5–30 km in radius. Surrounding the eye is the violent, stormy eyewall, approximately 10–30 km in width, formed as inward-moving, warm air turns upward into the storm. The strongest winds and heaviest precipitation are found in this area. Outside the eyewall of a typhoon, rainbands spiral inward to the eyewall. These rainbands are capable of producing heavy rain and strong winds (and occasionally tornadoes). Sometimes, there are gaps between the bands where no rain is found. The storm’s outer rainbands (often accompanied by typhoon or tropical storm–force winds) can extend approximately 100–1000 km from the center (Zhang et al., 2000; Zhu et al., 2000; Kossin and Schubert, 2004; Barnes and Barnes, 2014). In general, the strongest winds, heaviest rain, and deep convective thunderstorms are found in the eyewall, making it the most dangerous part of the typhoon. However, major disasters often occur in the outer spiral rainbands of the typhoon far from the eye and eyewall, and some studies have focused on wind speed changes from the eye to eyewall (no more than 200 km in radius), which can be explained by the Rankine Vortex Model (RVM) (or Modified Rankine Vortex Model) (Black and Willoughby, 1992; Mallen et al., 2005; Sitkowski et al., 2011). For this reason, the typhoon’s eye and eyewall areas were considered as a whole (i.e., the inner core of the typhoon system) in this study, with more attention focused on the wind speed changes in the outer region (spiral rainbands) of Mujigae, approximately 70–800 km away from the inner core (eye and eyewall).

During the movement of typhoons, multiple outer spiral rainbands form and disappear. But why do major disasters usually occur in the severe storm regions with severe convection, mesocyclones, and tornadic vortices in the spiral rainbands? Which are far away from the inner core (eye and eyewall) of the typhoon, as in the case of Mujigae? The velocity of the tangential wind increases with the increasing radius from the inner core to a certain range. When the radius reaches the threshold, the tangential velocity reaches its maximum, and then decreases gradually with increasing radius. This phenomenon has been observed in sandstorms, tornadic vortices, mesocyclonic vortices, and typhoons. In response to this phenomenon, a corresponding vortex velocity distribution model, that is, the RVM, was established by Rankine (1882) (Fig. 6a). The tangential velocity of a Rankine vortex with circulation Γ and radius R is written as:

| $\mu \left( r \right) = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}{{\rm{\Gamma }}r/2\pi {R^2}},\\{{\rm{\Gamma }}/2\pi r},\end{array}\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}{r \leqslant R,}\\{r > R.}\end{array}} \right.$ | (1) |

The RVM has been widely used as a diagnostic tool and improved to analyze and explain the observed tangential velocity, energy, and pressure structures in multiple fields, such as fluid mechanics, construction mechanics, and aerodynamics (Lee and Wurman, 2005; Cantor et al., 2006; Gan and He, 2009; Inoue et al., 2011; Tanamachi et al., 2013).

From the radar mosaic of South China and low altitude wind field distribution of Mujigae at 2000 BT 3 October (Fig. 6b), it was found that Typhoon Mujigae (red cycle) was located at 19.4°N, 113.5°E, while the air pressure of the inner core was 965 hPa and the maximum wind speed of the inner core was 38 m s–1. At 700 hPa, the wind speed in the outer area of the inner core region was approximately 16–18 m s–1, while it was 24–26 m s–1 at places away from the inner core by approximately 150 km to the northeast and 500 km to the south (figures omitted). As the distance continued to increase in both directions, the wind speed also decreased. At 850 hPa, the wind speed in the outer area of the inner core region was approximately 18 m s–1, while it was more than 20 m s–1 at places away from the inner core by approximately 200 km to the north, and more than 24 m s–1 at places away by approximately 500 km to the south of the inner core. As the distance continued to increase in both directions, the wind speed decreased correspondingly. From the radar mosaic of South China and low-altitude wind field distribution of Mujigae at 0800 BT 4 October (Fig. 6c), Typhoon Mujigae was located at 20.4°N, 111.6°E, and the air pressure of the inner core was 950 hPa while the maximum wind speed over the inner core was 48 m s–1. At 925 hPa, the wind speed in the outer area of the inner core region was approximately 10–12 m s–1, while it was more than 20 m s–1 at places away from the inner core by approximately 300 km to the northeast and 500 km to the south. As the distance continued to increase in both directions, wind speed decreased. At 850 hPa, the wind speed in the outer area of the inner core region was approximately 16 m s–1, while it was 24–26 m s–1 at places away by approximately 200 km to the north of the inner core and more than 20 m s–1 at places away by approximately 600 km to the south of the inner core. Moreover, as the distance continued to increase in both directions, wind speed decreased. From the radar mosaic of South China and low-altitude wind field distribution of Mujigae at 2000 BT 4 October (Fig. 6d), Typhoon Mujigae was located at 21.9°N, 109.5°E, where the air pressure of the inner core was 980 hPa and the maximum wind speed over the inner core was 33 m s–1. At 700 hPa, the wind speed in the outer area of the inner core region was approximately 12 m s–1, while it was more than 26 m s–1 at places away from the inner core by approximately 350 km to the northeast. As the distance continued to increase in both directions, the wind speed decreased. At 850 hPa, the wind speed in the outer area of the inner core region was approximately 16 m s–1, while it was 24–26 m s–1 at places away by approximately 200 km to the west of the inner core and more than 24 m s–1 at places away by approximately 350 km to the east of the inner core. As the distance continued to increase in both directions, wind speed decreased.

From the above analysis, it can be deduced that the wind speed gradually increased with the increase in the distance R from the inner core (eye and eyewall) in the outer spiral rainbands. When the threshold distance R was reached, the wind speed then gradually reduced with the increase in the distance. This is exactly what the RVM showed. This phenomenon fitted the RVM well (Fig. 6e) and was consistent with the simulation results of the Rankine vortex carried out by Chen et al. (2013). The mesocyclones and tornadic vortices that occurred in the outer spiral rainbands of Typhoon Mujigae can also be explained by the RVM (Fig. 6f). One good example can be found in the mesocyclone vortex and tornadic vortex that occurred at 224.6°, 25.3 km from the radar station, at 1536 BT 4 October, which were observed by the radar at 2.4° elevation and 1.2 km above ground level (AGL) at Guangzhou station (Fig. 6f). The mesocyclone vortex is indicated by the black cycle and the tornadic vortex by the inverted triangle. The absolute velocity of the vortex increased from 5 m s–1 at its center to more than 27 m s–1 outward; the actual maximum value of the velocity was –30 m s–1 (blue) toward the radar and 38 m s–1 (yellow) away from radar; the distance between the maximum positive and negative velocities was approximately 2 km; and the maximum rotational speed was 34 m s–1. The same vortex observed at 0.5° elevation and 0.4 km AGL had a maximum outflowing speed of 33 m s–1, a maximum inflowing speed of 30 m s–1, and an average rotational speed of 31.5 m s–1 (Wood and Brown, 1997; Wurman and Gill, 2000; Wurman, 2002; Wurman and Alexander, 2005). According to the mesoscale cyclone rotation speed index, the vortex that occurred at 1536 BT was a strong mesocyclone, and the velocity of the vortex outside the distance of the maximum speed decreased gradually, consistent with the RVM. Therefore, the formation mechanism for the severe storms and strong vortices in the outer spiral rainbands could be explained by the RVM.

|

| Figure 6 (a) The Rankine Vortex Model (RVM) for Typhoon Mujigae. (b) The radar mosaic of South China and the wind velocity fields (m s–1) at 700 and 850 hPa at 2000 BT 3 October. (c) The radar mosaic of South China and wind velocity fields (m s–1) at 850 and 925 hPa at 0800 BT 4 October. (d) The radar mosaic of South China and wind velocity fields (m s–1) at 850 and 925 hPa at 2000 BT 4 October. (e) The radar mosaic of South China (severe storms in Guangzhou) at 1600 BT 4 October overlaid by the RVM. (f) The velocity (m s–1) of a mesoscale cyclone monitored at 1536 BT 4 October in Shunde. |

The turbulence theory of atmospheric boundary layer dynamics can be used to give a reasonable interpretation of the formation of mesoscale cyclones and tornadic vortices in detail. The average thickness of the atmospheric boundary layer is approximately 1 km near earth’s surface. Therefore, the atmosphere in this layer should be regarded as a viscous fluid with turbulence characteristics (Roland, 1991; Yu et al., 2004). According to the fluid mechanical properties of a boundary layer, theoretical studies and experiments of viscous fluids carried out by Reynolds (1895), Richardson (1910) and Prandtl (1952) suggested that the occurrence of turbulence depends on the Reynolds Number of the flow field. The Reynolds Number is the dimensionless ratio of the fluid inertial force to the viscous force. When fluid disturbance occurs, the inertial force helps disturbances to obtain energy from the main stream, while the viscous force blocks the development of disturbances. The occurrence of atmospheric turbulence requires a high Reynolds Number and proper kinetic and thermodynamic conditions. Wind shear is a dynamic factor for the development of disturbances. When the wind shear is large enough, the fluctuation is unstable and turbulences will form. The uneven distribution of temperature is a thermodynamic factor that influences the atmospheric turbulence. Factors that are favorable for turbulence generation and development occur when the horizontal temperature distribution is uneven, the atmospheric baroclinicity is unstable, the atmospheric kinetic energy is unstable, atmospheric disturbances are relatively strong, and the wind speed and shear are very large. Moreover, the atmospheric turbulence is composed of various scales of vortices with a continuous distribution. Due to the stretching mechanism of vortices, a vortex of large or small size can form, even on a scale of 1 mm, and the rotational energy of a vortex can be gradually transferred from the secondary smaller-scale vortices down to the smallest vortex. Finally, the viscous stress of the smallest vortex transforms the rotational kinetic energy into heat or mechanical energy, which eventually dissipates. For Typhoon Mujigae, during the occurrence of the mesoscale cyclones and tornadic vortices, the base height of the severe storms within the atmospheric boundary layer was less than 1 km in the outer spiral rainbands, and the rainbands were located at the radius of maximum tangential wind speed, based on the RVM. The larger wind shear provided the dynamic condition, and the divergence in the vertical temperature from the warm ground to the cold upper level at 100 hPa provided the thermal condition. Both conditions were favorable for the development of disturbance instability and the formation of turbulent motions. As a result, various vortices at multiple scales formed in the outer spiral rainbands of Mujigae.

5 SummaryStrong disastrous typhoons with tornadoes in the outer spiral rainbands landing in China in the fall are very rare, and thus our understanding of them needs to improve. Accordingly, the present study analyzed the background, characteristics, and possible formation mechanisms for severe storms, mesoscale cyclones, and tornadic vortices in the outer rainbands of Typhoon Mujigae. The preliminary conclusions are as follows.

(1) The sea surface temperature near Mujigae was higher than 28°C, whereas an extreme cold temperature lower than –80°C existed at the upper level of the atmosphere at 100 hPa. This formed a strong unstable temperature gradient, boosting the formation and intensification of the typhoon. The subtropical high remained stable in northeastern South China Sea, and the ridge line of the subtropical high remained to the south of 24°N. Therefore, Typhoon Mujigae moved from southeast to north-west along the southwestern edge of the subtropical high.

(2) During the strengthening and landing periods of Mujigae, several mesoscale vortices and a waterspout occurred in the outer spiral rainbands, with severe storms occurring at places 500 km away from the inner core of the typhoon. After Mujigae landed in mainland China and before it weakened, two tornadic vortices occurred in Shunde and Panyu, approximately 350 km away from the inner core.

(3) The spatial and temporal distributions of the severe convective storms monitored by two radars were closely related to the position of the outer spiral rainbands of Mujigae. The severe storms monitored by the radar at Shanwei primarily occurred in a belt zone approximately 100 km in length and 60 km in width to the southwest of the radar station, and the severe storms monitored by the radar in Guangzhou primarily occurred in a zone approximately 150 km in length and 70 km in width that moved across the radar station from the southeast.

(4) During the developing and strengthening process of severe convection, which induced tornadoes, the base height of severe convection became lower when tornado occurred and reached its lowest height. After that, the base of severe convection began to rise. The period for the top of the severe convective systems to descend continuously was more than 20 min before tornado occurred. Thereby, the decrease in the top of convective systems has the potential to be used as an early warning indicator. The development and movement of severe storms and mesocyclones demonstrated a generating–strengthening–weakening–strengthening–weakening–dissipation pattern.

(5) The RVM was able to address why severe storms with the strongest echoes, mesocyclone vortices, and tornadic vortices frequently occur in spiral rainbands that are far from the inner core of a typhoon, such as Mujigae. Severe storms occur at the radius where the velocity of the wind field reaches its maximum value. At approximately 1000 BT 4 October, the wind velocity had its maximum value in the outer rainbands 500 km away from the inner core of Mujigae in Shanwei, and a waterspout occurred. After Mujigae landed at approximately 1530 BT, the wind velocity reached its maximum at the distance 350 km away from the inner core of Mujigae in Guangzhou. Accompanied by the effect of increasing elevation (Ji, 2007), the vertical wind shear was even stronger than before and two tornadoes occurred. The theory of atmospheric boundary layer turbulence and fluid mechanics provide good explanations for the formation of vortices of various scales.

The finer structure and evolution of the severe storms, mesocyclones, and tornadoes in the outer spiral rainbands of Mujigae will be further investigated in future work.

Acknowledgments. We acknowledge the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions and advice on this work. We thank Yuhang Chen for assistance in figure plotting.

| Barnes C. E., Barnes G. M., 2014: Eye and eyewall traits as determined with the NOAA WP-3D lower-fuselage radar. Mon. Wea. Rev., 142, 3393–3417. DOI:10.1175/MWR-D-13-00375.1 |

| Benjamin W. G., Zhang F., Markowski P., 2011: Multiscale processes leading to supercells in the landfalling outer rainbands of Hurricane Katrina (2005). Wea. Forecasting, 26, 828–847. DOI:10.1175/WAF-D-10-05049.1 |

| Black M. L., Willoughby H. E., 1992: The concentric eyewall cycle of Hurricane Gilbert. Mon. Wea. Rev., 120, 947–957. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1992)120<0947:TCECOH>2.0.CO;2 |

| Cantor B. A., Kanak K. M., Edgett K. S., 2006: Mars Orbiter Camera observations of Martian dust devils and their tracks (September 1997 to January 2006) and evaluation of theoretical vortex models. J. Geophys. Res., 111(E12), E12002. DOI:10.1029/2006JE002700 |

| Chen L. S., 2010: Tropical meteorological calamities and its research evolution. Meteor. Mon., 36, 101–110. |

| Chen X. M., Zhao K., Lee W. C., et al.,2013: The improvement to the environmental wind and tropical cyclone circulation retrievals with the modified GBVTD (MGBVTD) technique. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol., 52, 2493–2508. DOI:10.1175/JAMC-D-13-031.1 |

| Daniel J. K., Bryan G. H., Rotunno R., Durran D. R., 2007: The triggering of orographic rainbands by small-scale topography. J. Atmos. Sci., 64, 1530–1549. DOI:10.1175/JAS3924.1 |

| Ding Z. Y., Wang Y., Shen X. Y., et al.,2009: On the causes of rainband breaking and asymmetric precipitation in Typhoon Haitang (2005) before and after its landfall. J. Trop. Meteor., 25, 513–520. |

| Fang C., Zheng Y. Y., 2007: The analysis of mesocyclone product from the Doppler weather radar. Meteor. Mon., 33, 16–20. |

| Feng J. Q., Tang D. Z., Yu X. D., et al.,2010: The accuracy statistics of mesocyclone identification products from CINRAD/SA. Meteor. Mon., 36, 47–52. |

| Franklin C. N., Holl G. J., May P. T., 2006: Mechanisms for the generation of mesoscale vorticity features in tropical cyclone rainbands. Mon. Wea. Rev., 134, 2649–2669. DOI:10.1175/MWR3222.1 |

| Gan W. J., He Y. B., 2009: Analysis of tornado forces on low-rise buildings according to the model of transmitting Rankine vortex. Sichuan Build. Sci., 35, 84–86, 89. |

| Glen S. R., Wilhelmson R. B., 2006: Finescale spiral band features within a numerical simulation of Hurricane Opal (1995). Mon. Wea. Rev., 134, 1121–1139. DOI:10.1175/MWR3108.1 |

| Inoue H. Y., Kusunoki K., Kato W., et al.,2011: Finescale Doppler radar observation of a tornado and low-level mesocyclones within a winter storm in the Japan sea coastal region. Mon. Wea. Rev., 139, 351–369. DOI:10.1175/2010MWR3247.1 |

| Ji C. X., Xue G. Y., Zhao F., et al.,2007: The numerical simulation of orographic effect on the rain and structure of Typhoon Rananim during landfall. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 31, 233–244. |

| Kossin J. P., Schubert W. H., 2004: Mesovortices in Hurricane Isabel. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 85, 151–153. DOI:10.1175/BAMS-85-2-151 |

| Lee W. C., Wurman J., 2005: Diagnosed three-dimensional axisymmetric structure of the Mulhall tornado on 3 May 1999. J. Atmos. Sci., 62, 2373–2393. DOI:10.1175/JAS3489.1 |

| Li Q. Q., Wang Y. Q., 2012: A comparison of inner and outer spiral rainbands in a numerically simulated tropical cyclone. Mon. Wea. Rev., 140, 2782–2805. DOI:10.1175/MWR-D-11-00237.1 |

| Mallen K. J., Montgomery M. T., Wang B., 2005: Reexamining the near-core radial structure of the tropical cyclone primary circulation: Implications for vortex resiliency. J. Atmos. Sci., 62, 408–425. DOI:10.1175/JAS-3377.1 |

| Matthew D. E., Link M. C., 2009: Miniature supercells in an offshore outer rainband of Hurricane Ivan (2004). Mon. Wea. Rev., 137, 2081–2104. DOI:10.1175/2009MWR2753.1 |

| Matthew J. O., Fuelberg H. E., 2014: A parameter for forecasting tornadoes associated with landfalling tropical cyclones. Wea. Forecasting, 29, 1238–1255. DOI:10.1175/WAF-D-13-00086.1 |

| McCaul E. W., 1991: Buoyancy and shear characteristics of hurricane-tornado environments. Mon. Wea. Rev., 119, 1954–1978. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1991)119<1954:BASCOH>2.0.CO;2 |

| Prandtl, L., 1952: Essentials of Fluid Dynamics: With Applications to Hydraulics Aeronautics, Meteorology, and Other Subjects. Hafner Publishing Company, New York, 460 pp. |

| Rankine, W. J. M., 1882: A Manual of Applied Physics. 10th ed., Charles Griff and Co., 663 pp. |

| Reynolds O., 1895: On the dynamical theory of incompressible viscous fluids and the determination of the criterion. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 186, 123–164. DOI:10.1098/rsta.1895.0004 |

| Richardson, L. F., 1910: The approximate arithmetical solution by finite differences of physical problems involving differential equations, with an application to the stresses in a masonry dam. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 210, 307–357. Bibcode: 1911RSPTA.210..307R. doi:10.1098/rsta.1911.0009. |

| Robert R. L., White A., 1998: Improvement of the WSR-88D mesocyclone algorithm. Wea. Forecasting, 13, 341–351. DOI:10.1175/1520-0434(1998)013<0341:IOTWMA>2.0.CO;2 |

| Roland, B. S., 1991: An Introduction to Boundary Layer Meteorology: Chinese Edition. Translated by Yang, C. X., China Meteorological Press, 738 pp. (in Chinese) |

| Shou, S. W., S. S. Li, and X. P. Yao, 2003: Mesoscale Meteorology. China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 191–203. (in Chinese) |

| Sitkowski M., Kossin J. P., Rozoff C. M., 2011: Intensity and structure changes during hurricane eyewall replacement cycles. Mon. Wea. Rev., 139, 3829–3847. DOI:10.1175/MWR-D-11-00034.1 |

| Tanamachi R. L., Bluestein H. B., Xue M., et al.,2013: Near-surface vortex structure in a tornado and in a sub-tornado-strength convective-storm vortex observed by a mobile, W-band radar during VORTEX2. Mon. Wea. Rev., 141, 3661–3690. DOI:10.1175/MWR-D-12-00331.1 |

| Todd A. M., Knupp K. R., 2013: An analysis of cold season supercell storms using the synthetic dual-Doppler technique. Mon. Wea. Rev., 141, 602–624. DOI:10.1175/MWR-D-12-00035.1 |

| Wang Y., Ding Z. Y., 2008: Structural and characteristic analyses of spiral rain bands around the landing of Typhoon Haitang. J. Nanjing Instit. Meteor., 31, 352–362. |

| Williamson, P. S., and S. L. Hays, 2006: The Federal Committee for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research (FCMSSR): Doppler Radar Meteorological Observations. Federal Meteorological Handbook No. 11, Part C, WSR-88D Products and Algorithms. Department of Commerce/National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Washington DC, U.S., 349 pp. |

| Wood V. T., Brown R. A., 1997: Effects of radar sampling on single-Doppler velocity signatures of mesocyclones and tornadoes. Wea. Forecasting, 12, 928–938. DOI:10.1175/1520-0434(1997)012<0928:EORSOS>2.0.CO;2 |

| Wu Z. F., Ye A. F., Hu S., et al.,2004: The statistic characteristics of mesoscale and microscale systems with the new generation weather radar. J. Trop. Meteor., 20, 391–400. |

| Wurman J., 2002: The multiple-vortex structure of a tornado. Wea. Forecasting, 17, 473–505. DOI:10.1175/1520-0434(2002)017<0473:TMVSOA>2.0.CO;2 |

| Wurman J., Gill S., 2000: Finescale radar observations of the Dimmitt, Texas (2 June 1995), Tornado. Mon. Wea. Rev., 128, 2135–2164. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(2000)128<2135:FROOTD>2.0.CO;2 |

| Wurman J., Alexer C. R., 2005: The 30 May 1998 Spencer, South Dakota, storm. Part II: Comparison of observed damage and radar-derived winds in the tornadoes. Mon. Wea. Rev., 133, 97–119. DOI:10.1175/MWR-2856.1 |

| Yu, X. D., X. P. Yao, T. N. Xiong, et al., 2006: Doppler Weather Radar Principle and Operational Applications. China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 314 pp. (in Chinese) |

| Yu, Z. H., M. Q. Miao, Q. R. Jiang, et al., 2004: Fluid Mechanics. 3th ed., China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 378 pp. (in Chinese) |

| Zhang, P. C., B. Y. Du, and T. P. Dai, 2000: Radar Meteorology. 3th ed., China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 511 pp. (in Chinese) |

| Zhang Y. P., Yu X. D., Wu Z., et al.,2012: Analysis of the two tornado events during a process of regional torrential rain. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 70, 961–973. |

| Zhao K., Zhou Z. D., Hu D. M., et al.,2007: The rainband structure of Typhoon Paibian (0606) during its landfall from dual-Doppler radar observations. J. Nanjing Univ. (Nat. Sci.), 43, 606–620. |

| Zheng F., Zhong J. F., Lou W. P., 2010: Analysis of a tornado in outside-region of the super typhoon " Sepat” in 2007. Plateau Meteor., 29, 506–513. |

| Zheng Y. Y., Zhang B., Wang X. H., et al.,2015: Analysis of typhoon–tornado weather background and radar echo structure. Meteor. Mon., 41, 942–952. |

| Zhou H. G., 2010: Mesoscale spiral rainband structure of super typhoon Wipha (0713) observed by dual-Doppler radar. Trans. Atmos. Sci., 33, 271–284. |

| Zhou X. G., Wang X. M., Yu X. D., et al.,2012: Application of excess rotation kinetic energy in distinguishing the tornadic and non-tornadic mesocyclones in China. Plateau Meteor., 31, 137–143. |

| Zhu J. J., Wang L., Huang X. S., et al.,2005: Hail forecasting related to mesocyclone product of CINRAD/SA. Meteor. Mon., 31, 38–42. |

| Zhu, Q. G., J. R. Lin, S. W. Shou, et al., 2000: Principles and Methods of Synoptic Meteorology. 4th ed., China Meteorological Press, 649 pp. (in Chinese) |

2017, Vol. 31

2017, Vol. 31