中国气象学会主办。

文章信息

- 黄艳艳, 王会军. 2020.

- HUANG Yanyan, WANG Huijun. 2020.

- 太平洋年代际振荡的年代际预测方法

- A possible approach for the decadal prediction of PDO

- 气象学报, 78(2): 177-186.

- Acta Meteorologica Sinica, 78(2): 177-186.

- http://dx.doi.org/10.11676/qxxb2020.026

文章历史

-

2019-08-30 收稿

2020-01-02 改回

2. 中国科学院大气物理研究所,竺可桢-南森国际研究中心,北京,100029

2. Nansen-Zhu International Research Centre,Institute of Atmospheric Physics,Chinese Academy of Sciences,Beijing 100029,China

年代际气候预测致力于未来1—10 a或者30 a内的年平均、多年平均和年代际平均等多时间尺度平均的气候状态的预测,因其重要的社会经济及环境价值,近年来受到社会的广泛关注(Meehl,et al,2009)。年代际预测已经是政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)第5次评估报告的重要内容之一。世界气候研究计划第6次耦合模式比较计划(Eyring,et al,2016)更是专门设立了年代际气候预测计划(Boer,et al,2016)。

太平洋年代际振荡(PDO)是气候系统的主要内部年代际变率之一,对气候系统其他成员具有显著影响(Newman,et al,2016)。例如,PDO的年代际转折被认为对东亚和南亚(Fan,et al,2017;Yu,et al,2015;Zhu,et al,2015)、澳大利亚(Arblaster,et al,2002)和北美(McCabe,et al,2004,2012)气候的年代际变化,以及最近的全球变暖停滞(Kosaka,et al,2013)贡献显著。同时,PDO对于农业、水资源和渔业也有显著影响(Mantua,et al,1997;Miller,et al,2004)。

预测气候系统的内部年代际变率非常必要,同时也充满挑战。目前进行年代际气候预测主要依靠初始化的气候模式,因此,初始化方案是当前年代际气候预测能否成功的关键(Meehl,et al,2014;周天军等,2017;Mehta,et al,2019)。然而,初始化冲击一直是模式初始化面临的重要挑战(He,et al,2017;Meehl,et al,2014)。虽然,初始化在个别气候模式中展现了一定的改进模式预测PDO的能力(Mochizuki,et al. 2010,2012),但是,由于北太平洋内部年代际变率机制的争议性(Meehl,et al,2014)和对于初始状态不稳定的内部敏感性(Branstator,et al,2012a,2012b),总的说来,相比于北太平洋(Guemas,et al,2012;Kim,et al,2012;Meehl,et al,2014;Newman,2013;Wang,et al,2018),初始化在北大西洋具有更高的改进技巧( Smith,et al,2010;Yang,et al,2013)。此外,由于PDO的年代际转折可能跟大范围的随机强迫有关,因此对PDO的年代际转折进行预测目前认为存在困难(Newman,et al,2016)。另外,已有研究利用统计模型/动力-统计模型进行年代际预测,且主要是针对地表温度的年代际预测(Fu ,et al,2011;罗菲菲等,2015),针对PDO的预测还罕有尝试。总的来说,针对PDO的预测成果还远不能满足实际需求。

最近提出的年际增量方法(王会军等,2012)给气候预测领域提供了一个新思路。相比传统预测方法将变量相对气候态的异常作为预测对象,年际增量方法将变量的年际增量(当年的值与前一年的差值)作为预测对象。然后将预测的年际增量加上前一年的观测值得到最终预测结果。由于前期观测值包含了年代际信号(王会军等,2010),且气候模式中的年际增量可以有效降低模式的系统性误差(Huang,et al,2014)。因此年际增量方法在气候年际预测中取得较好的成绩(Fan,et al,2008,2009;Fan,2009,2011;Tian,et al,2015)。

在传统年代际气候预测中,一般先预测气候未来几年/十年中每一年的情况,再通过滤波或者滑动平均得到预测的年代际气候变率。文中直接将PDO的年代际变率作为预测对象,并提出增量方法来构建预测模型,该方法有助于提高有效样本以及从前期观测中得到更多有用的年代际信号。

2 数据和方法由于冬季北太平洋物理过程显示出显著的年代际信号(Mantua,et al,1997;Deser,et al,2006;Yeh,et al,2011;Wang,et al,2012),因此文中将冬季(12、1、2月)的PDO年代际变率作为预测对象。年代际变率通过5 a滑动平均得到,标记年份为滑动5 a的中间年份。年代际PDO指数定义为5 a滑动平均的冬季北太平洋(20°—70°N)海表温度异常(SSTA)经验正交函数分解(EOF)主模态的时间序列,其中SSTA为海表温度首先扣除全球平均的海表温度,再扣除气候态年循环(Mantua,et al,1997)。

4组月平均数据被用来预测PDO年代际变率,(1)NOAA v3b的海表温度(SST),水平分辨率为2°×2°(Smith,et al,2008);(2)SODA v2.1.6的海表高度(SSH),水平分辨率为0.5°×0.5°(Carton,et al,2008);(3)NOAA-CIRES 20CR 2c的海平面气压(SLP),水平分辨率为2°×2°(Compo,et al,2011);(4)哈得来中心的海冰密集度(SIC),水平分辨率为1°×1°(Rayner,et al,2003)。

基于年代际PDO指数,计算了3 a增量形式(DI)的PDO(DI_PDO),即年代际PDO指数当年的值与其3 a前的差值(式(1))。如1906年的DI_PDO为1906年的年代际PDO指数减去1903年的年代际PDO指数。文中,DI_PDO首先被视为预测对象,基于3个增量形式的预测因子构建统计预测模型,用来预测DI_PDO。增量形式的预测因子为季节平均的预测因子去除线性趋势后的5 a滑动平均的3 a增量形式。最终预测的年代际PDO为统计模型预测得到的当年DI_PDO加上观测中3 a前的年代际PDO指数(式(2))。

| ${\rm{DI}}\_{\rm{PD}}{{\rm{O}}_{{i}}} = {\rm{PD}}{{\rm{O}}_{{i}}} - {\rm{PD}}{{\rm{O}}_{{{i}} - 3}}$ | (1) |

式中,PDOi和PDOi-3分别为年代际PDO指数在当年和3 a前的值,DI_PDOi为增量PDO在当年的值。

| ${\rm{PD}}{{\rm{O}}_{{i}}} = {\rm{PDO}}_{{{i}} - 3}^{{\rm{obs}}} + {\rm{DI}}\_{\rm{PDO}}_{{i}}^{{\rm{s}} - {\rm{model}}}$ | (2) |

式中,

对原始数据采用5 a滑动平均来得到年代际信号,为了避免虚假的预测技巧,将传统检验方法经过适度调整,用来衡量统计预测模型的预测技巧。一是剔除5 a的交叉检验(Michaelsen,1987):预测对象目标年的预测值,通过剔除研究时段内的5 a值(目标年及其前后2 a的预测对象及对应5 a的预测因子),利用剩余年份构建的预测模型得到。此步骤重复,直到所有年份均得到交叉检验结果。研究时段的最初3 a/最后3 a的交叉检验结果为剔除最初5 a/最后 5 a,利用剩余年份建模预测得到。二是独立试报:预测模型为滚动的67 a,即预测对象在目标年的预测值,通过利用超前于目标年72(69) a至6(3) a前的预测因子(预测对象)构建的预测模型得到。这样做是为了避免预测模型用到任何预测时段的信息。如,利用1903—1969年增量形式的预测因子和1906—1972年DI_PDO构建预测模型,预测1975年的DI_PDO;利用1904—1970年增量形式预测因子和1907—1973年DI_PDO构建预测模型,预测1976年的DI_PDO;依此类推。

9 a滑动窗口的滑动t 检验(MTT)被用来检验年代际PDO指数的年代际转折点。相关分析的显著性采用t检验,其中有效样本N*的计算基于(Bretherton,et al,1999;Ding,et al,2012)

| ${N^*} = N\frac{{1 - {r_1}{r_2}}}{{1 + {r_1}{r_2}}}$ | (3) |

式中,N为研究样本的所有时间步长,r1和r2分别为相关分析中两个变量滞后1 a的自相关系数。

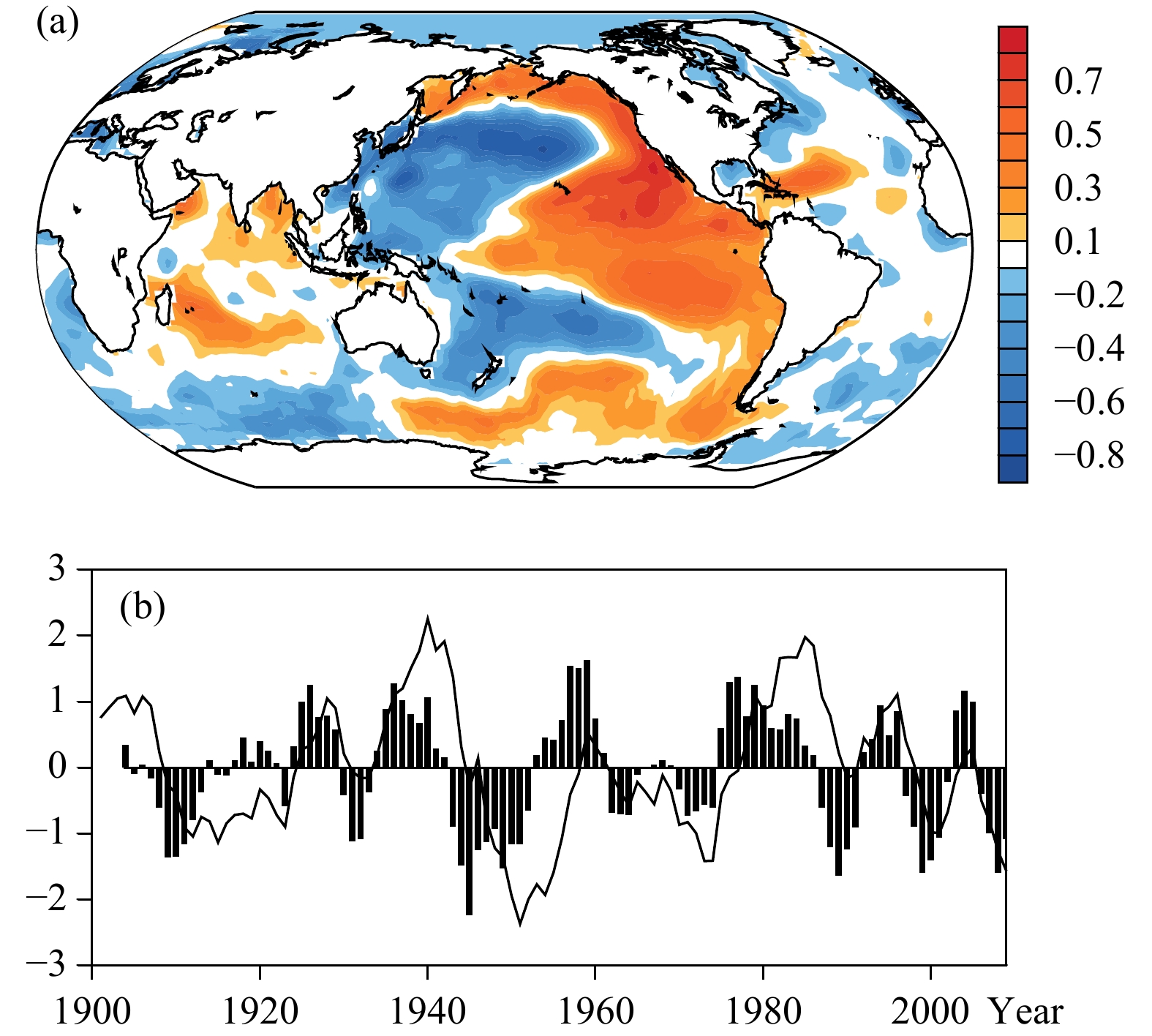

3 PDO的年代际预测图1a给出了年代际PDO指数(北太平洋冬季年代际SSTA EOF第一模态)对应的全球海表温度的空间分布。该模态可以解释27%的北太平洋SSTA的年代际变率总方差。PDO的正位相对应于北太平洋的中部和西部的负SSTA,以及北太平洋东部和赤道东太平洋的正SSTA。图1b同时给出了1901—2009年冬季年代际PDO指数及其DI_PDO。

|

| 图 1 (a) 1901—2009年年代际PDO指数与5 a滑动平均的冬季全球海表温度相关系数及 (b) 1901—2009年年代际PDO指数 (实线) 和1903—2009年DI_PDO (柱) Fig. 1 (a) Correlation coefficient of the 5 a running DJF global SST with the decadal PDO index during 1901—2009 and (b) decadal PDO index during 1901—2009 (solid line) and the DI_PDO during 1903—2009 (bars) |

基于增量形式的预测因子构建一个经验统计模型预测DI_PDO。该模型的建立主要通过以下3个步骤:(1)Newman等(2016)总结出的PDO变率主要与阿留申低压、源于热带的遥相关以及中纬度海洋动力过程有关,基于以上3个物理过程寻找潜在的预测因子;(2)采用5 a滑动平均得到年代际变率,为了防止预测模型用到任何预测时段的信息,预测因子必须至少超前DI_PDO 3 a;(3)采用99%信度水平的F检验的逐步回归来确定最后模型中的预测因子。逐步回归的基本原理是筛选出与预测对象最相关的因子,并剔除与该预测因子显著相关的因子,故最终筛选得到的预测因子应该是与预测对象显著相关,并彼此独立。

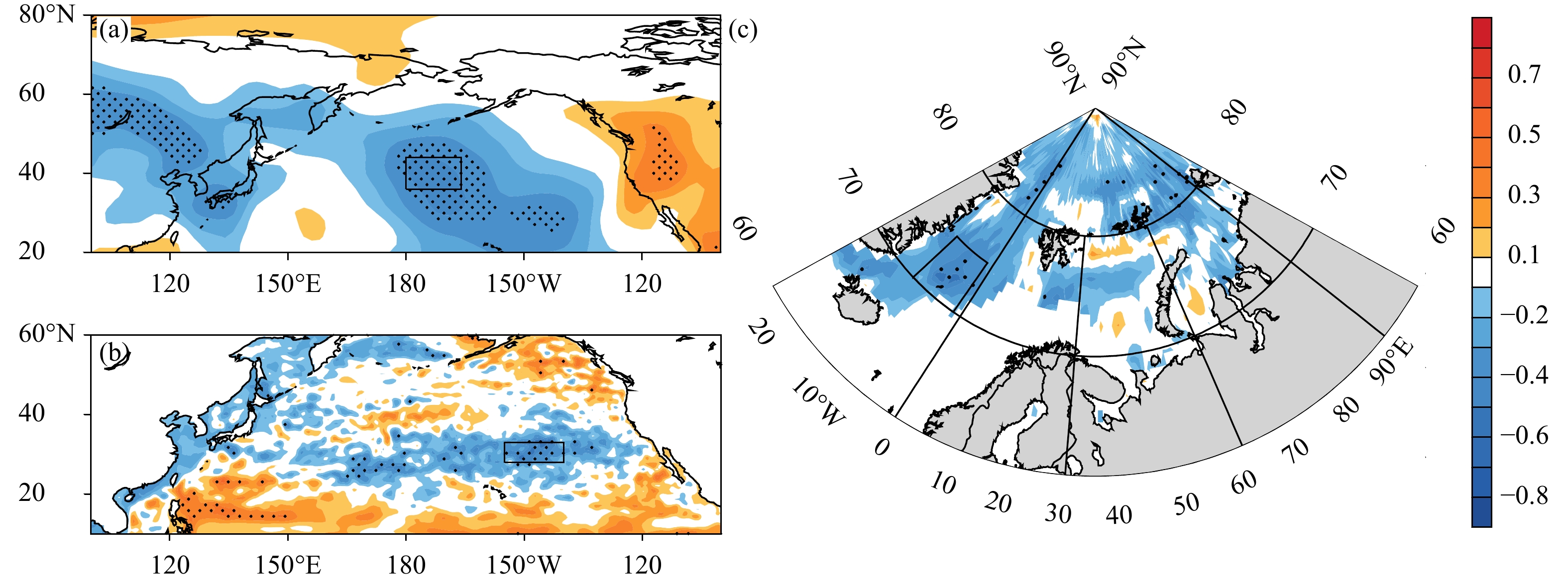

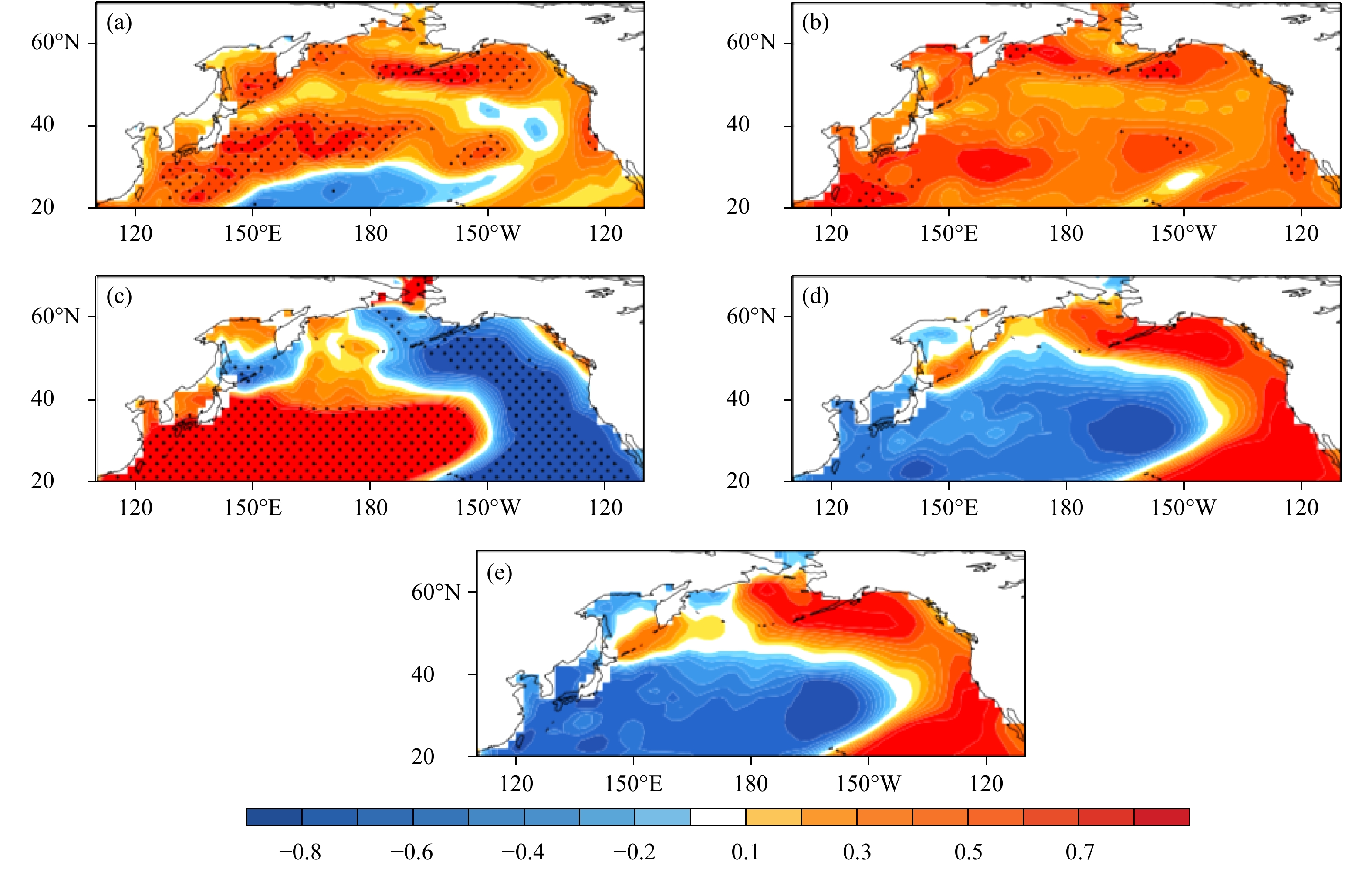

基于以上3个步骤,选择3个超前3 a的预测因子,分别为增量形式的秋季阿留申低压(DI_AL)、增量形式的冬季格陵兰海冰(DI_SIC)和增量形式的春季中太平洋海表高度(DI_SSH)。大部分北太平洋海表温度变率主要受大气驱动(Smirnov,et al,2014),但由于埃克曼输送或者通量—驱动SSTA形态的物理过程,大气的变率会超前于海表温度的变率(Davis,1976;Deser,et al,1997)。前期的阿留申低压是驱动PDO变率的重要大气强迫之一(图2a)(Schneider,et al,2005;Newman,et al,2016)。同时,格陵兰海冰可以通过影响北极涛动来影响PDO变率(图2b)(Lindsay,et al,2005;Sun,et al,2006)。此外,西北太平洋的副极地锋区是PDO变率的大值区(Nakamura,et al,2003)。前期副极地锋区的热容量可以通过热动力响应来驱动PDO变率(图2c)(Qiu,2003;Newman,et al,2016)。

|

| 图 2 1906—2009年冬季DI_PDO与超前3 a预测因子的相关系数 (a. 秋季 (9—11月) 增量形式的海平面气压,b. 春季 (3—5月) 增量形式的海表高度,c. 冬季 (12—2月) 增量形式的海冰密集度;加点区域为通过90%的信度t检验,矩形表示预测因子的关键区,分别为DI_AL (36°—44°N,180°—166°W),DI_SSH (28°—33°N,155°—140°W),DI_SIC (70°—75°N,15°—2°W)) Fig. 2 Correlation coefficient of the DJF DI-PDO during 1906—2009 with (a. SON DI of sea level pressure leading by three years, b. MAM DI of sea surface height, c. DJF DI of sea ice concentration. The dotted area indicates values significant at the 90% confidence level using studentt test. The boxes in panels indicate the key areas for calculating the DI_Predictors,including DI_AL (36°—44°N, 180°—166°W),DI_SSH (28°—33°N, 155°—140°W) and DI_SIC (70°—75°N, 15°—2°W)) |

| ${\rm{DI}}\_{\rm{PDO}} = - 0.31{\rm{DI}}\_{\rm{AL}} - 0.36{\rm{DI}}\_{\rm{SIC}} - 0.37{\rm{DI}}\_{\rm{SSH}}$ | (4) |

式中,DI_AL为增量形式的9—11月海平面气压(36°—44°N,180°—166°W)区域平均值;DI_SIC为增量形式的3—5月海冰密集度(70°—75°N,15°—2°W)区域平均值;DI_SSH为增量形式的12—2月海表高度(28°—33°N,155°—140°W)的区域平均值。DI_AL、DI_SIC和DI_SSH分别可以解释DI_PDO方差的9.6%、13%、13.7%。

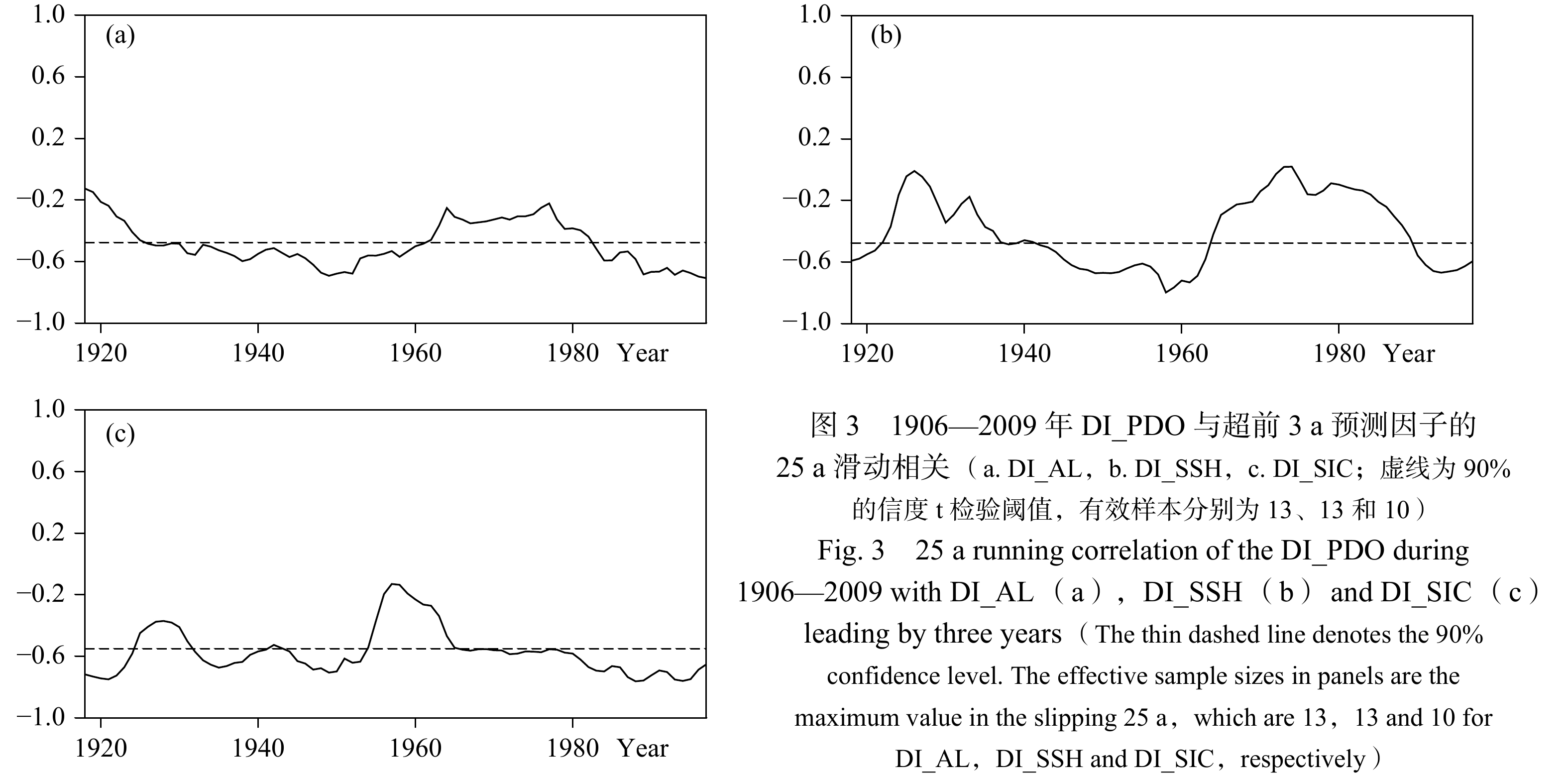

1906—2009年DI_PDO与超前3 a的DI_AL、DI_SSH和DI_SIC的相关系数分别为−0.43、−0.48和−0.43。尽管研究时段3个预测因子都与DI_PDO显著相关,但由于研究时段超过100 a,相关关系不可避免存在年代际变化(图3)。DI_PDO与超前3 a的DI_AL和DI_SSH的相关均在1960—1980年减弱(图3a和b),这可能会影响模型的预测效果,这也可能是预测模型中预测因子解释方差不高的原因。

|

| 图 3 |

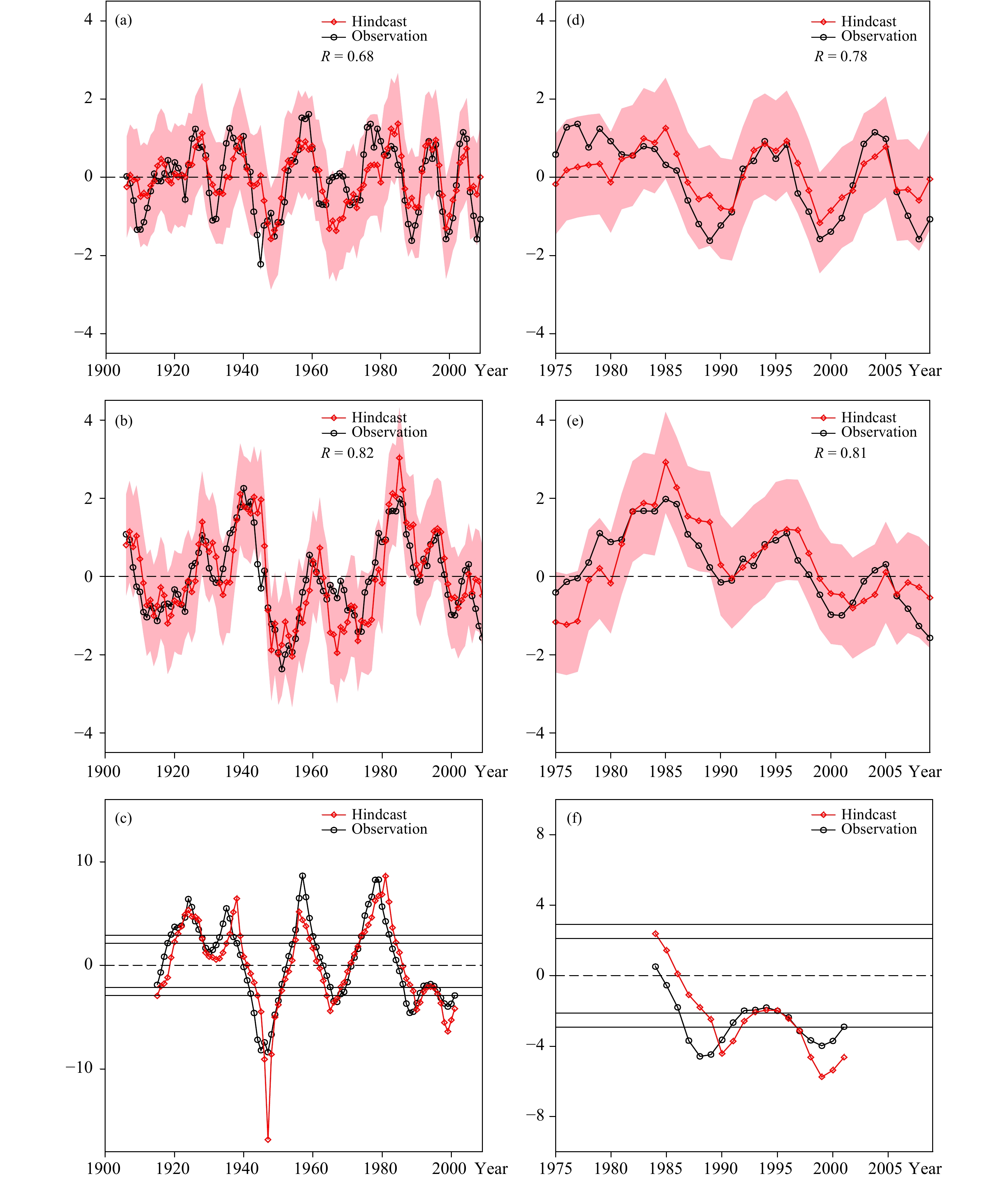

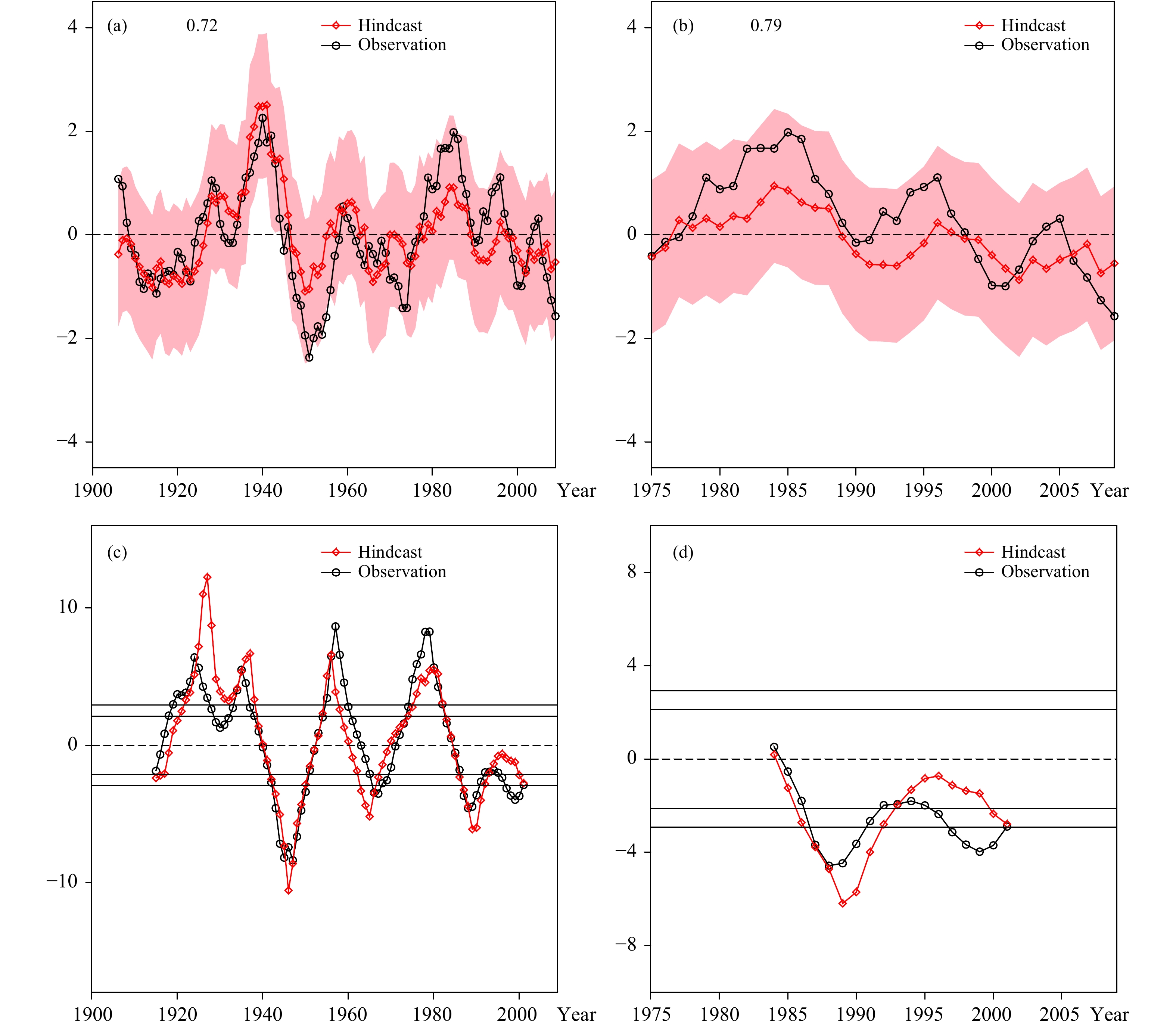

图4a给出了经验统计预测模型剔除5 a交叉检验的1906—2009年DI_PDO。由于之前提到的预测因子和DI_PDO相关关系的年代际变化,果然1960—1980年预测的DI_PDO和观测有较大的不同,表明统计预测模型在该时段预测水平有限。其余年份,预测的DI_PDO变率和振幅与观测在一定程度上一致,特别是1980年之后。观测和预测的DI_PDO 1906—2009年的相关系数为0.68,达到99.9%信度水平。经验统计预测模型对DI_PDO显示出较高的预测水平。

|

| 图 4 DI_PDO (a、d) 和PDO (b、e) 的预测及PDO的9 a滑动t检验 (c、f)(a、b、c. 1906—2009年剔除5 a的交叉检验结果,d、e、f. 1975—2009年独立试报结果;浅粉色色域表示95%的预测置信区间。R为观测和预测的相关系数;c和f中的细实线分为别95%和99%的信度水平阈值) Fig. 4 Prediction of the DJF DI_PDO (a,d),PDO (b,e) and the regime shifts of the PDO detected by moving t test with 9 a moving window (c,f) in cross-validation with five years excluded for the period of 1906—2009 (a—c) and in independent hindcast for the period of 1975—2009 (d—f)(The pink shading is the 95% prediction interval.R is the temporal correlation coefficient between predictions and observations. The thin black solid lines in Panel c and f indicate the confidence thresholds for 95% and 99% levels,respectively) |

经验统计模型预测得到的DI_PDO加上3 a前观测的年代际PDO指数,得到最终预测的年代际PDO指数(图4b)。观测和预测的PDO在1960—1980年依然具有明显的不一致。但在其余年份,最终预测的PDO指数和观测结果无论是在变率还是在振幅上都相当吻合,并且预测的PDO指数成功捕捉到了每一次的年代际转折。观测和预测的PDO指数1906—2009年的相关系数达0.82。相比观测的PDO年代际转折点,预测PDO的年代际转折点的误差不大于2 a(图4c)。增量方法显示出对年代际PDO指数的有效预测水平。

对1975—2009年的DI_PDO进行独立试报,进一步验证经验统计模型的预测技巧(图4d)。模型对于1975—1980年的DI_PDO的预测水平有限,预测的DI_PDO的振幅小于0.5,比观测小很多。对1980年之后的DI_PDO统计模型显示出很高的预测水平。观测和预测的1975—2009年DI_PDO的相关系数为0.78,高于99%的信度水平。最终预测的1975—2009年年代际PDO指数与观测的相关系数为0.81(图4e)。观测中1975—2009年的年代际PDO指数具有2次年代际转折,分别为1988/1989和1999/2000年。预测年代际PDO指数第1次转折发生在1990/1991年,比观测晚2 a,第2次发生在1999/2000年,与观测完全一致(图4f)。总的说来,经验统计模型结合增量方法对于年代际PDO指数显示出较高的预测水平,其中包括年代际转折的预测。

为了与增量方法进行对比,建立基于原始变量形式的统计模型,直接预测年代际PDO指数。根据年代际PDO指数与超前3 a的预测因子的相关(图5),为了选出最相关区域,相比DI_AL和DI_SSH的关键区,阿留申低压和海表高度的关键区有了一些改变,海冰密集度的关键区移至喀拉海以北的区域,主要考虑到格陵兰海已不再是显著区。

|

| 图 5 1906—2009年年代际PDO指数与超前3 a预测因子的相关系数 (a. 9—11月海平面气压,b. 3—5月海表高度,c. 12—2月海冰密集度;加点区域表示通过90%的信度水平,矩形表示预测因子的关键区,分别为阿留申低压 (35°—50°N,175°E—160°W),海表高度 (30°—35°N,170°—155°W) 和海冰密集度 (78°—85°N,70°—90°E)) Fig. 5 Correlation coefficient of DJF PDO during 1906—2009 with SON sea level pressure leading by three years (a),MAM sea surface height (b) and DJF sea ice concentration (c)(The dotted area indicates the values significant at/above the 90% confidence level. The boxes are the key areas for calculating Predictors,which are AL(35°—50°N,175°E—160°W),SSH(30°—35°N,170°—155°W) and SIC (78°—85°N,70°—90°E),respectively) |

| ${\rm{PDO}} = - 0.36{\rm{AL}} - 0.35{\rm{SIC}} - 0.37{\rm{SSH}}$ | (5) |

式中,AL为9—11月海平面气压(35°—50°N,175°E—160°W)的区域平均值;SIC为12—2月海冰密集度(78°—85°N,0°—90°E)的区域平均值;SSH为3—5月海表高度(30°—35°N,170°—155°W)的区域平均值。AL、SIC和SSH分别可以解释年代际PDO指数方差的13%、12.3%和13.7%。

1906—2009年年代际PDO指数与超前3 a的AL、SSH和SIC的相关系数分别为−0.48、−0.55和−0.56,均通过了90%的信度水平。基于原始变量的统计模型似乎对年代际PDO指数显示了部分技巧(图6a和c)。然而,交叉检验的PDO未能预测出1950年前后PDO的超强负位相(图6a)。在独立试报中(图6b和d),预测的1975—2009年PDO不仅振幅要远小于观测结果,还在1980年之后一直保持在负位相,显然不对。总的说来,基于原始变量的统计预测模型对于年代际PDO指数的预测技巧远低于增量方法。

|

| 图 6 同图4,但为基于超前3 a的阿留申低压、海冰密集度和海表高度的统计预测模型直接预测的年代际PDO指数 (a. 剔除五年交叉检验的1906—2009年年代际PDO指数,c. 其滑动9 a的滑动t检验结果,b. 独立试报的1975—2009年年代际PDO指数,d. 其9 a的滑动t检验结果) Fig. 6 Same as in Fig.4but for the PDO prediction of the statistical model AL,SSH and SIC leading by 3 a (a. the cross-validated PDO during 1906—2009,c . 9 a MTT results,b. the predicted PDO during 1975—2009 in the independent hindcast,d. 9 a MTT results) |

统计预测模型结合增量方法被进一步用来尝试预报北太平洋(20°—70°N)每个格点上的冬季海表温度距平的年代际变率。式(6)和(4)类似,只是将预测对象变为北太平洋每个格点上的3 a增量形式的海表温度距平(DI_SSTA)。同样,增量形式的预测因子超前DI_SSTA 3 a。最终预测的海温距平为预测DI_SSTA加上观测3 a前的值。文中只给出独立试报中19754—2009年的结果。

| ${\rm{DI}}\_{\rm{SSTA}} = {{a}}{\text •}{\rm{DI}}\_{\rm{AL}} + {{b}}{\text •}{\rm{DI}}\_{\rm{SIC}} + {{c}}{\text •}{\rm{DI}}\_{\rm{SSH}}$ | (6) |

对于1975—2009年北太平洋冬季DI_SSTA,有预测技巧的地方出现在黑潮延伸区至中太平洋和50°N以北的太平洋(图7a)。尽管最终预测的海温距平在北太平洋并不是全部显著(图7b),但却成功捕捉到北太平洋海温距平在1999年的年代际转折(图7c),年代际转折的预测对于目前气候模式还较为困难(Newman,et al,2016)。此外,进一步检验了经验统计模型结合增量方法对PDO空间模态的预测能力。图7d给出了基于式(4)最终预测的年代际PDO指数(图4e)与基于式(6)最终预测的北太平洋海温距平(图7b)独立试报结果1975—2009年的相关系数。对应于正位相的PDO,负的海温距平出现在北太平洋西部至中部,正的海温距平出现在北太平洋东部,与观测一致(图7e),图7d和e的空间相关系数达到0.95。以上结果说明,统计预测模型结合增量方法可以有效预测北太平洋海温距平的年代际转折以及PDO的空间模态。

|

| 图 7 观测和独立试报的1975—2009年冬季预测结果的相关系数 (a. DI_SSTA,b SSTA,c. 预测的SSTA在2000—2009年与1980—1999年的差值,d. 基于式(4)独立试报的年代际PDO指数与基于式(6)独立试报的SSTA 1975—2009年的相关系数,e. 观测结果中1975—2009年年代际PDO指数与SSTA的相关系数;加点区域表示通过90%(a和b)/95%(c)的信度水平) Fig. 7 Correlation coefficients of the observations with the predicted DJF DI_SSTA (a) and the final predicted DJF SSTA (b) in the independent hindcast during 1975—2009,(c) the difference in the predicted DJF SSTA in the independent hindcast between 2000—2009 and 1980—1999,the correlation coefficients of the PDO index with the SSTA over the North Pacific in independent hindcast(d) and observations(e)(The dotted area indicates the values significant at/above the 90% (a, b)/95% (c) confidence level using studentt test) |

通过构建经验统计预测模型并结合增量方法预测了1906—2009年冬季年代际PDO指数。首先利用5 a滑动平均得到年代际变率,然后选取超前3 a的DI_AL、DI_SSH和DI_SIC为预测因子构建预测模式,预测3 a增量的PDO(DI_PDO),最后将预测的DI_PDO加上3 a前观测PDO得到最后预测的年代际PDO指数。增量方法对于年代际PDO指数显示很高的预测技巧,特别是对于PDO年代际转折的预测。

增量方法的主要优势除了可以从前期观测中得到有用的年代际信号,还可以在相关分析中增加有效样本。如1906—2009年DI_PDO与超前3 a格陵兰DI_SIC的相关中,有效样本为19,但如果是1906—2009年PDO与同样格陵兰区域的海冰密集度的相关,有效样本仅为8。增量方法为直接将变量的年代际变率作为预测对象提供了可能。

上述研究为目前的年代际气候预测提供了新思路,特别是年代际转折的预测。增量方法同样可以应用到气候年代际内部变率其他模态(如大西洋年代际振荡)或者其他气候变量的年代际预测。此外,增量方法还可以应用到目前的气候模式年代际预测产品中。因为增量形式的变量可以在一定程度上减小模式的系统性误差,也许气候模式对于增量形式变量的预测技巧高于原始形式。采用气候模式预测的增量形式加上前期观测值,也许可以提高当前气候模式的年代际气候预测技巧。同样,也可以针对增量形式的变量构建动力-统计预测模型来进一步改进气候模式的年代际预测技巧。

罗菲菲, 李双林. 2015. 动力统计相结合的未来30年东亚气温年代际预测. 中国科学: 地球科学, 45(4): 402-413. Luo F F, Li S L. 2014. Joint statistical-dynamical approach to decadal prediction of East Asian surface air temperature. Sci China: Earth Sci, 57(12): 3062-3072

|

王会军, 张颖, 郎咸梅. 2010. 论短期气候预测的对象问题. 气候与环境研究, 15(3): 225-228. DOI:10.3878/j.issn.1006-9585.2010.03.01 |

王会军, 范可, 郎咸梅等. 2012. 我国短期气候预测的新理论、新方法和新技术. 北京: 气象出版社, 120-139. Wang H J, Fan K, Lang X M, et al. 2012. Advances in Climate Prediction Theory and Technique of China. Beijing: China Meteorological Press, 120-139 (in Chinese)

|

周天军, 吴波. 2017. 年代际气候预测问题: 科学前沿与挑战. 地球科学进展, 32(4): 331-341. |

Arblaster J, Meehl G, Moore A. 2002. Interdecadal modulation of Australian rainfall. Climate Dyn, 18(6): 519-531. DOI:10.1007/s00382-001-0191-y |

Boer G J, Smith D M, Cassou C, et al. 2016. The Decadal Climate Prediction Project (DCPP) contribution to CMIP6. Geosci Model Dev, 9(10): 3751-3777. DOI:10.5194/gmd-9-3751-2016 |

Branstator G, Teng H. 2012a. Potential impact of initialization on decadal predictions as assessed for CMIP5 models. Geophys Res Lett, 39: L12703. DOI:10.1029/2012GL051974 |

Branstator G, Teng H, Meehl G A, et al. 2012b. Systematic Estimates of Initial-Value Decadal Predictability for Six AOGCMs. J Climate, 25: 1827-1846. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00227.1 |

Bretherton C S, Widmann M, Dymnikov V P, et al. 1999. The effective number of spatial degrees of freedom of a time-varying field. J Climate, 12(7): 1990-2009. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(1999)012<1990:TENOSD>2.0.CO;2 |

Carton J A, Giese B S. 2008. A reanalysis of ocean climate using Simple Ocean Data Assimilation (SODA). Mon Wea Rev, 136(8): 2999-3017. DOI:10.1175/2007MWR1978.1 |

Compo G P, Whitaker J S, Sardeshmukh P D, et al. 2011. The twentieth century reanalysis project. Quart J Roy Meteor Soc, 137(654): 1-28. DOI:10.1002/qj.776 |

Davis R E. 1976. Predictability of sea surface temperature and sea level pressure anomalies over the North Pacific Ocean. J Phys Oceanogr, 6(3): 249-266. DOI:10.1175/1520-0485(1976)006<0249:POSSTA>2.0.CO;2 |

Deser C, Timlin M S. 1997. Atmosphere-Ocean interaction on weekly timescales in the North Atlantic and Pacific. J Climate, 10(3): 393-408. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(1997)010<0393:AOIOWT>2.0.CO;2 |

Deser C, Phillips A S. 2006. Simulation of the 1976/77 climate transition over the North Pacific: Sensitivity to tropical forcing. J Climate, 19(23): 6170-6180. DOI:10.1175/JCLI3963.1 |

Ding Q H, Steig E J, Battisti D S, et al. 2012. Influence of the tropics on the southern annular mode. J Climate, 25(18): 6330-6348. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00523.1 |

Eyring V, Bony S, Meehl G A, et al. 2016. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci Model Dev, 9(5): 1937-1958. DOI:10.5194/gmd-9-1937-2016 |

Fan K, Wang H J, Choi Y J. 2008. A physically-based statistical forecast model for the middle-lower reaches of the Yangtze River Valley summer rainfall. Chinese Sci Bull, 53(4): 602-609. DOI:10.1007/s11434-008-0083-1 |

Fan K, Wang H J. 2009. A new approach to forecasting typhoon frequency over the Western North Pacific. Wea Forecasting, 24(4): 974-986. DOI:10.1175/2009WAF2222194.1 |

Fan K. 2009. Predicting winter surface air temperature in Northeast China. Atmos Oceanic Sci Lett, 2(1): 14-17. DOI:10.1080/16742834.2009.11446770 |

Fan K. 2011. A prediction model for Atlantic named storm frequency using a year-by-year increment approach. Wea Forecasting, 25(6): 1842-1851. |

Fan Y, Fan K. 2017. Pacific Decadal Oscillation and the decadal change in the intensity of the interannual variability of the South China Sea summer monsoon. Atmos Oceanic Sci Lett, 10(2): 162-167. DOI:10.1080/16742834.2016.1256189 |

Fu C B, Qian C, Wu Z H. 2011. Projection of global mean surface air temperature changes in next 40 years: Uncertainties of climate models and an alternative approach. Sci China Earth Sci, 54(9): 1400-1406. DOI:10.1007/s11430-011-4235-9 |

Guemas V, Doblas-Reyes F J, Lienert F, et al. 2012. Identifying the causes of the poor decadal climate prediction skill over the North Pacific. J Geophys Res Atmos, 117(D20): D20111. |

He Y J, Wang B, Liu M M, et al. 2017. Reduction of initial shock in decadal predictions using a new initialization strategy. Geophys Res Lett, 44(16): 8538-8547. DOI:10.1002/2017GL074028 |

Huang Y Y, Wang H J, Fan K. 2014. Improving the prediction of the summer Asian–Pacific Oscillation using the interannual increment approach. J Climate, 27(21): 8126-8134. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00209.1 |

Kim H M, Webster P J, Curry J A. 2012. Evaluation of short-term climate change prediction in multi-model CMIP5 decadal hindcasts. Geophys Res Lett, 39(10): L10701. |

Kosaka Y, Xien S P. 2013. Recent global-warming hiatus tied to equatorial Pacific surface cooling. Nature, 501(7467): 403-407. DOI:10.1038/nature12534 |

Lindsay R W, Zhang J. 2005. The thinning of arctic sea ice, 1988-2003: Have we passed a tipping point?. J Climate, 18(22): 4879-4894. DOI:10.1175/JCLI3587.1 |

Mantua N J, Hare S R, Zhang Y, et al. 1997. A Pacific interdecadal climate oscillation with impacts on salmon production. Bull Amer Meteor Soc, 78(6): 1069-1080. DOI:10.1175/1520-0477(1997)078<1069:APICOW>2.0.CO;2 |

McCabe G J, Palecki M A, Betancourt J L. 2004. Pacific and Atlantic Ocean influences on multidecadal drought frequency in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 101(12): 4136-4141. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0306738101 |

McCabe G J, Ault T R, Cook B I, et al. 2012. Influences of the El Niño Southern Oscillation and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation on the timing of the North American spring. Int J Climatol, 32(15): 2301-2310. DOI:10.1002/joc.3400 |

Meehl G A, Goddard L, Murphy J, et al. 2009. Decadal prediction: Can it be skillful?. Bull Amer Meteor Soc, 90(10): 1467-1486. DOI:10.1175/2009BAMS2778.1 |

Meehl G A, Goddard L, Boer G, et al. 2014. Decadal climate prediction: An update from the trenches. Bull Amer Meteor Soc, 95(2): 243-267. DOI:10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00241.1 |

Mehta V M, Mendoza K, Wang H. 2019. Predictability of phases and magnitudes of natural decadal climate variability phenomena in CMIP5 experiments with the UKMO HadCM3, GFDL-CM2. 1, NCAR-CCSM4, and MIROC5 global earth system models. Climate Dyn, 52(5-6): 3255-3275. |

Michaelsen J. 1987. Cross-validation in statistical climate forecast models. J Climate Appl Meteor, 26(11): 1589-1600. DOI:10.1175/1520-0450(1987)026<1589:CVISCF>2.0.CO;2 |

Miller A J, Chai F, Chiba S, et al. 2004. Decadal-scale climate and ecosystem interactions in the North Pacific Ocean. J Oceanogr, 60(1): 163-188. DOI:10.1023/B:JOCE.0000038325.36306.95 |

Mochizuki T, Ishii M, Kimoto M, et al. 2010. Pacific Decadal Oscillation hindcasts relevant to near-term climate prediction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 107(5): 1833-1837. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0906531107 |

Mochizuki T, Chikamoto Y, Kimoto M, et al. 2012. Decadal prediction using a recent series of MIROC global climate models. J Meteor Soc Japan, 90A: 373-383. DOI:10.2151/jmsj.2012-A22 |

Nakamura H, Kazmin A S. 2003. Decadal changes in the North Pacific oceanic frontal zones as revealed in ship and satellite observations. J Geophys Res Oceans, 108(C3): 3078. DOI:10.1029/1999JC000085 |

Newman M. 2013. An empirical benchmark for decadal forecasts of global surface temperature anomalies. J Climate, 26(14): 5260-5269. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00590.1 |

Newman M, Alexander M A, Ault T R, et al. 2016. The Pacific Decadal oscillation, revisited. J Climate, 29(12): 4399-4427. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-15-0508.1 |

Qiu B. 2003. Kuroshio Extension variability and forcing of the Pacific Decadal Oscillations: Responses and potential feedback. J Phys Oceanogr, 33(12): 2465-2482. DOI:10.1175/2459.1 |

Rayner N A, Parker D E, Horton E B, et al. 2003. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J Geophys Res Atmos, 108(D14): 4407. DOI:10.1029/2002JD002670 |

Schneider N, Cornuelle B D. 2005. The forcing of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. J Climate, 18(21): 4355-4373. DOI:10.1175/JCLI3527.1 |

Smirnov D, Newman M, Alexander M A. 2014. Investigating the role of ocean-atmosphere coupling in the North Pacific Ocean. J Climate, 27(2): 592-606. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00123.1 |

Smith D M, Eade R, Dunstone N J, et al. 2010. Skilful multi-year predictions of Atlantic hurricane frequency. Nat Geosci, 3(12): 846-849. DOI:10.1038/ngeo1004 |

Smith T M, Reynolds R W, Peterson T C, et al. 2008. Improvements to NOAA's historical merged land-ocean surface temperature analysis (1880-2006). J Climate, 21(10): 2283-2296. DOI:10.1175/2007JCLI2100.1 |

Sun J Q, Wang H J. 2006. Relationship between Arctic Oscillation and Pacific Decadal Oscillation on decadal timescale. Chinese Sci Bull, 51(1): 75-79. |

Tian B Q, Fan K. 2015. A skillful prediction model for winter NAO based on Atlantic sea surface temperature and Eurasian snow cover. Wea Forecasting, 30(1): 197-205. DOI:10.1175/WAF-D-14-00100.1 |

Wang T, Otterå O H, Gao Y Q, et al. 2012. The response of the North Pacific decadal variability to strong tropical volcanic eruptions. Climate Dyn, 39(12): 2917-2936. DOI:10.1007/s00382-012-1373-5 |

Wang T, Miao J P. 2018. Twentieth-century Pacific Decadal Oscillation simulated by CMIP5 coupled models. Atmos Oceanic Sci Lett, 11(1): 94-101. DOI:10.1080/16742834.2017.1381548 |

Yang X S, Rosati A, Zhang S Q, et al. 2013. A predictable AMO-like pattern in the GFDL fully coupled ensemble initialization and decadal forecasting system. J Climate, 26(2): 650-661. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00231.1 |

Yeh S W, Kang Y J, Noh Y, et al. 2011. The North Pacific climate transitions of the winters of 1976/77 and 1988/89. J Climate, 24(4): 1170-1183. DOI:10.1175/2010JCLI3325.1 |

Yu L, Furevik T, Otterå O H, et al. 2015. Modulation of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation on the summer precipitation over East China: A comparison of observations to 600-years control run of Bergen Climate Model. Climate Dyn, 44(1-2): 475-494. DOI:10.1007/s00382-014-2141-5 |

Zhu Y L, Wang H J, Ma J H, et al. 2015. Contribution of the phase transition of Pacific Decadal Oscillation to the late 1990s' shift in East China summer rainfall. J Geophys Res Atmos, 120(17): 8817-8827. DOI:10.1002/2015JD023545 |

2020, Vol. 78

2020, Vol. 78