文章信息

- 孔维尧, 孙权, 刘鑫鑫, 曲丽, 王福友, 姚明远, 邹红菲.

- Kong Weiyao, Sun Quan, Liu Xinxin, Qu Li, Wang Fuyou, Yao Mingyuan, Zou Hongfei.

- 基于红外相机监测的汪清自然保护区东北豹种群动态

- Population Dynamic of Far Eastern Leopard(Panthera pardus orientalis) in Wangqing Nature Reserve Based on Infrared Camera Monitoring

- 林业科学, 2019, 55(5): 188-196.

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2019, 55(5): 188-196.

- DOI: 10.11707/j.1001-7488.20190521

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2018-10-07

- 修回日期:2019-03-12

-

作者相关文章

2. 吉林省林业科学研究院长白山动物资源与生物多样性吉林省重点实验室 长春 130033;

3. 东北虎豹国家公园管理局汪清分局 汪清国家级自然保护区管理局 汪清 133200

2. Jilin Provincial Academy of Forestry Science Jilin Provincial Key Laboratory of Wildlife and Biodiversity in Changbai Mountain Changchun 130033;

3. Northeast Tiger and Leopard National Park Administration Wangqing Suboffice Wangqing National Nature Reserve Administration Wangqing 133200

东北豹(Panthera pardus orientalis)是分布最北、种群数量最小的豹亚种,在IUCN红皮书中评估濒危等级为“极危”(Jackson et al., 2012),是最濒危的猫科动物亚种之一。东北豹曾广泛分布于我国长白山区、俄罗斯远东地区南部和朝鲜半岛(Nowell et al., 1996),进入20世纪以来,随着人为活动增强,东北豹栖息地迅速缩减,目前仅分布于俄罗斯滨海边疆区西南部(Hebblewhite, 2011)以及我国长白山区大龙岭、老爷岭地区,哈尔巴岭、张广才岭区域有零星记录(孔维尧等, 2017;蒋劲松等, 2015)。

东北豹种群数量系统评估始于20世纪70年代,Abramov等(1974)的雪地调查结果显示,此时俄罗斯的东北豹分布区已局限在滨海边疆区南部3个相互孤立的栖息地,种群数量不足46只。1985年,东北豹在2个北部分布区消失,俄罗斯境内东北豹分布区仅存位于滨海边疆区西南端的1处,种群数量25~35只(Pikunov et al., 1985),此后波动在22~44只之间(Pikunov et al., 1997; Aramilev et al., 2000; Pikunov et al., 2003;2009)。我国东北豹种群调查始于1998年的虎豹雪地同步调查,调查确认东北豹数量3~5只(Yang et al., 1998)。2012年、2014年吉林省进行了2次东北豹专项雪地调查,种群评估数量分别为8~11只(孔维尧等, 2017)和9只(蒋劲松等, 2015)。与种群数量调查相比,东北豹其他研究相对较少,包括遗传多样性(Uphyrkina et al., 2002;Sugimoto et al., 2014)、食性分析(Sugimoto et al., 2016)、疾病(Sulikhan et al., 2018)、家域与社会结构(Salmanova, 2012; Vitkalova et al., 2016)、扩散路径分析(Miquelle et al., 2015)、潜在栖息地预测(Hebblewhite et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2015)等领域。

红外相机监测技术是近年来迅速兴起的一项新型研究方法,因其准确性、长期性、隐蔽性和无损伤性等特点,已广泛应用于生物多样性监测、动物行为学、物种保护与评估、物种时空分布格局、种群数量和密度评估等领域(李佳等,2017)。Karanth(1995)首次采用红外相机开展孟加拉虎(Panthera tigris tigris)的研究,随后相机监测在猫科动物研究中得到广泛应用(Maffei et al., 2004; Di Bitetti et al., 2006; Dillon et al., 2007; Trolle et al., 2003; Soisalo et al., 2006; Kelly et al., 2008; Matiukhina et al., 2016)。Kostyria等(2003)首次将相机监测应用于东北豹研究,2014年之后相关文献数量迅速增加。Zhang等(2018)根据猎物丰富度评估了汪清保护区东北豹容纳量;Qi等(2015)分析了汪清保护区北部—珲春保护区北部东北豹空间分布与猎物丰富度的关系,结果显示狍(Capreolus capreolus)的密度是影响东北豹分布的最主要原因;蒋劲松等(2015)和Wang等(2016)通过在珲春、汪清地区的相机监测发现,我国东北豹主要分布于中俄边境地区并沿老爷岭南部向西扩散,种群数量稳定增长;Vitkalova等(2016)应用相机监测技术评估了俄罗斯豹地公园的东北豹种群数量和密度,发现东北豹在1年监测期的识别个体数在74~79只,在90日监测期则下降到51~55只,种群密度约为每km2 1只。

汪清自然保护区是我国重要的东北豹分布区(蒋劲松等, 2015;Wang et al., 2016),但此区域东北豹种群数量及分布的相关研究报道较少。本研究基于2013—2017年相机监测的数据,分析了保护区内东北豹种群数量和分布情况的长期动态,以期为这一濒危物种的保护提供科学依据。

1 研究区概况吉林汪清自然保护区位于吉林省东部延边朝鲜族自治州汪清县和珲春市境内,地理坐标130°23′07″— 131°03′19″E,43°05′33″—43°30′17″N,面积67 434 hm2。属于中温带湿润温凉季风气候区,全年平均气温为1.5 ℃,年降水量为450~600 mm。保护区内以中低山为主,西南和东北较高,中间较低,海拔均在1 500 m以下,大部分山体海拔在1 000 m以下,相对高度多为200~600 m。海拔700 m以下是以蒙古栎(Quercus mongolica)林、杨(Populus spp.)和榆(Ulmus spp.)等杂木林为主的阔叶林,海拔700~1 100 m是红松(Pinus koraiensis)阔叶林为主的混交林带,在海拔800 m以上以红松与云冷杉(Picea sp.-Abies sp.)混交林为主,海拔1 100~1 500 m为以云冷杉为主并混有红松的暗针叶林。保护区动物资源丰富,分布有国家Ⅰ级重点保护野生动物5种、Ⅱ级重点保护野生动物28种,其中包括虎(Panthera tigris)、豹(Panthera pardus)、棕熊(Ursus arctos)、黑熊(Ursus thibetanus)为代表的顶级食肉动物。

2 研究方法 2.1 相机布设根据5年内收集的豹信息记录,在保护区内的豹重点分布区布设3 km×3 km网格,每个网格中布设一对相机。相机距地面高度为40~50 cm,距离动物可能通过路线3~5 m(Soutyrina et al., 2012)。相机监测时段主要集中在春季和秋季,以回避冬季低温和夏季多雨。每个监测季所有相机同时工作时段(即全部相机架设完毕日期至所有相机停止工作最早日期)不少于40天。相机布设于保护区的兰家、西南岔和杜荒子林场,2013年布设相机15对,2014年春季起增至22对,2017年秋季增至42对(图 1)。

|

图 1 汪清自然保护区红外相机架设位置 Fig. 1 Location of infrared cameras in Wangqing Nature Reserve |

采用相对丰富指数(relative abundance index, RAI) (拍摄事件数量×100/相机总监测天数)计算东北豹相对丰富度(O’Brien et al., 2003)。以拍摄到东北豹的相机数量(每个位点记为1)除以有效回收相机数量(即排除丢失、未工作的相机数量)计算拍摄到东北豹相机比率(Vitkalova et al., 2016)。

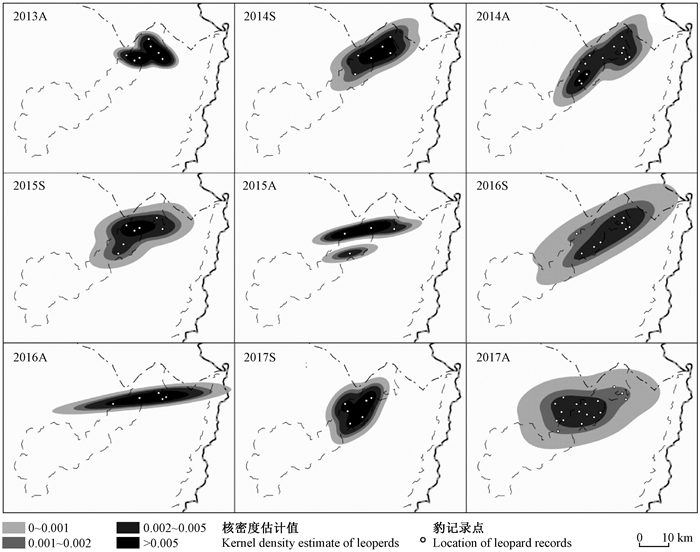

以每个监测季为单位,在ArcGIS 10.2中将拍摄到东北豹历次相机位点转为矢量文件,采用Fixed Kernel Density评估对监测区内东北豹分布概率密度进行核密度估计,采用99%容量等值线定义东北豹分布区(Hebblewhite et al., 2011)并在ArcGIS中计算分布区面积。核密度估计以及等值线划分在GME 0.7.3中计算(Hawthorne, 2016)。

2.3 东北豹个体确认将体侧图像清晰、完整的豹照片和视频截图输入ExtractCompare软件提取体侧斑纹并计算斑纹相似指数,相似指数0.9以上的确认为同一只个体。仅拍摄到体侧部分影像、尚可辨认的模糊影像以及与其他影像相似指数低于0.9的图像采用双盲分组识别的方法进行人工识别(Kelly et al., 2008)。根据个体在不同监测季的出现与消失,计算种群迁入率(immigration rate, Rim)与迁出率(emigration rate, Rem)。2017年秋季迁入率采用2013年开始架设的22台相机数据进行统计。Rim、Rem计算公式为:

| $ {\text{Rim}}_{i}=n_{i} / N_{i} ; \text { Rem }_{i}=m_{i} / N_{i}。$ |

式中:ni为第i个监测季新记录到的成年个体数量,mi 为第i个监测季记录到但在第i+1监测季未记录到的成年个体数量;Ni为第i个监测季识别出的成年个体总数量。未离开雌豹独立生活的幼豹不计入迁入率和迁出率的统计。

2.4 东北豹种群密度评估将每个监测季所有相机同时工作时段定义为有效监测期,采用有效监测期内获取的数据进行种群密度评估。每3天设为一个监测时间单位,以降低0记录频率对种群密度评估的影响(Soutyrina et al., 2012)。使用CAPTURE软件中进行闭合种群检验、适宜模型评估和种群数量估计。本研究对CAPTURE软件中的4种多次标识-重捕法种群估计模型进行评估:M0(Null model),即假设每只动物在所有监测时段捕获率均一致;Mh(Heterogeneity effects model),每只动物捕获率不同,但不同个体不同时间段捕获率无差异;Mb(Behaviour effects model),动物在捕获前后捕获率不同,但无个体和时间差异;Mt(Time effects model),动物在不同时段捕获率不同,但在同一时段不同个体捕获率相同。CPATURE软件会对各种模型给出分值在0~1之间的模型选择标准,根据选择标准得分评估4种假设适宜性。采用卡方检验评估M0与Mb模型、M0与Mt模型的拟合度,分析动物在捕获前后的行为响应以及不同的监测时段捕获率的差异;通过Mh模型拟合优度检验(Mh假设vs非Mh假设),评估Mh模型适宜性。由于Mh模型更符合动物的实际捕获率,且对非闭合种群耐受度更高(Otis et al., 1978),在Mh标准得分并非最高的监测季,仍利用Mh模型估计种群数量(Karanth,1998; Soutyrina et al., 2012)。采用有效监测期内拍摄个体数量与模型估计数量比值,计算种群总捕获率(Rexstad et al., 1991; Karanth,1998)。东北豹种群密度即估计种群数量除以有效监测面积。由于布设相机栅格以外的动物也有可能被拍摄到,相机有效监测面积定义为监测区最外侧相机点向周边延伸一定范围的缓冲区(Otis,1978; Karanth,1998),缓冲区的大小设为东北豹平均家域面积的半径——8 km(Salmanova, 2012; Vitkalova et al., 2016)。

3 结果与分析 3.1 东北豹拍摄频率与空间分布动态在9个监测季内的东北豹拍摄情况及分布区动态变化见表 1,种群空间分布核密度估计见图 2。监测期间,RAI指数波动在0.34~2.12之间,拍摄到豹的相机比率为19%~65%。受相机监测布设数量影响,2013年秋季(架设15对相机)东北豹分布区最小(201 km2),2017年(架设42对相机)分布区上升为992 km2。在相机数量固定为22对的7个监测季,东北豹分布区面积变化在300~500 km2左右,但2016年春季分布区范围达到890 km2。

|

|

|

图 2 汪清保护区东北豹时空分布动态格局 Fig. 2 Spatiotemporal distribution pattern of leopards in Wangqing Nature Reserve |

在研究期间9个监测季内,共识别东北豹个体9只,其中成年雌性个体3只、雄性个体3只,幼崽2只,性别不明个体1只。2013年秋季识别确认个体数量最高,共5只个体,其中包括1雌2幼的家庭群;2014年春季识别成体数最多,共4只个体。2015年秋季和2016年秋季监测区仅识别豹1只,均为L5M。监测区内分布最稳定的是雄豹L5M,在8个监测季有拍摄记录,其次是雌豹L11,在5个监测季有记录。豹个体记录情况及迁入率、迁出率见表 2。

|

|

模型选择及闭合种群检验结果见表 3。Mh模型选择标准得分在4个监测季最高,在其他5个监测季得分仅次于M0。Mb、Mt模型评估捕获率与M0模型评估捕获率也无显著差异,此结果表明动物在捕获前后以及各不同监测时间段捕获率无显著变化。

|

|

东北豹捕获率与种群密度估计结果见表 4。研究期间东北豹种群密度在0.12~0.88只·(100 km2)-1间波动,种群总捕获率总体较高,但2017年春季拍摄个体仅占种群评估数量的0.43。

|

|

雪地调查主要依据掌垫宽度通过专家评估判断个体数量,但由于足迹清晰度、测量误差的原因,特别是不同专家判定标准不一致,评估数量存在较大误差(Pikunov et al., 2000; Aramilev et al., 2000)。由于东北豹家域重叠度可高达59%,依据足迹大小判断会在很大程度低估种群数量(Salmanova, 2012)。与雪地调查相比,相机监测具有不受气候影响、监测期灵活(李佳等,2017)、便于查询检索(O’Connell et al., 2011)等优点,在个体判断上具有其他手段不可比拟的优势,因此相机监测已成为评估大型猫科动物数量与分布的主流方法(Soisaloa et al., 2006;马鸣等, 2006;Wang et al., 2009; Qi et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016; Matiukhina et al., 2016)。本文研究区在2012年2—3月、2014年1月和2017年2月曾进行东北豹雪地调查,评估数量分别为0~2只、3只和2只,均低于临近监测季相机监测拍摄到的个体数。

采用核密度估计分析的9个监测季东北豹分布概率密度反映出较明显的时空异质性。西南岔林场始终是东北豹活动最频繁区域,该区域植被以红松阔叶混交林为主,人为活动较少,猎物资源丰富(孔维尧,2017),以上均为东北豹偏好生境(Hebblewhite et al., 2011)。这一结果也表明动物分布概率密度可以反映生境适宜度(张桂铭等,2013)。与此对应,兰家区域东北豹分布概率密度在2015年后明显降低。兰家山体高度多在700 m以上,高海拔带来的较深积雪是东北豹分布的一个限制性因子(Gavashelishvili et al., 2008;Qi et al., 2015)。2015年春季—2017年秋季兰家林场狍的RAI(6.15±0.86)与西南岔林场(7.02±1.11)差异并不明显,但野猪(Sus scrofa) RAI仅为后者的18.83%。Qi等(2015)2014冬季在汪清保护区的研究表明野猪密度与东北豹密度负相关,与本研究2015年后的结果不符,但2014年春、秋2季的监测结果支持了Qi等(2015)的结论。2014年春季兰家林场狍RAI为西南岔林场的2.17倍,野猪RAI仅为后者的14.11%。与此对应,2014年春季兰家林场东北豹分布概率高于西南岔林场,但随着狍丰富度差异的缩小,东北豹频繁活动区域向野猪丰富度更高的西南岔林场转移。以上结果表明东北豹对猎物丰富度的响应机制存在弹性适应。Sugimoto等(2016)的研究表明东北豹捕食狍的频率高于野猪,本研究表明在猎物充足的情况下,东北豹更偏好在狍密度较高的兰家林场活动,虽然此区域的海拔并不处于最适宜范围;而在猎物丰富度降低的条件下,东北豹活动频繁区域向野猪丰富度更高、海拔更低的西南岔林场转移。

猎物丰富度与东北豹种群数量也存在一定的相关性。在狍RAI最高的2014年春、秋2个监测季,东北豹的RAI、拍摄个体数和种群密度均处于较高水平。2016年秋东北豹RAI(0.34)、拍摄个体数(1只)均处于最低值,而狍的RAI(7.71±1.46)也处于较低水平。狍RAI最低值出现在2017年春季,该监测季豹的RAI(0.59)仅高于2016年秋,但识别个体数(3只)仅次于2014年春,种群评估密度[0.88±0.41只·(100 km2)-1]也是监测期最高的评估数值。这种评估密度与猎物丰富度的反常关系可能是由于该监测季东北豹并非处于严格意义的闭合种群状态以及监测范围小而产生的种群密度高估。

闭合种群是对种群数量进行评估的前提条件。由于豹生活史较长,在90天内的监测期,违反闭合种群假设的主要情况是动物进入监测区后短时间内又离开监测区,此类情况可在M0 vs Mb卡方检验结果中表现出来,并被定义为“拍摄羞怯反应”(Karanth et al., 1998)。CAPTURE软件通过比较不同个体首次与末次捕获时间间距来进行闭合种群检验(Otis et al., 1978; White et al., 1982)。影响闭合种群检验的因素包括:1)种群数量,样本量小容易导致出现拒绝假设的结果(Otis, 1978),White(1982)建议小于20只的种群不宜采用此检验结果判定闭合种群假设。2)监测时长,一些监测期超过10个月的研究虽然也通过了闭合种群检验,但P值明显降低(Karanth, 1995; Wang et al., 2009; Simcharoen et al., 2007)。3)捕获时间间隔,首次和末次捕获时间间距越近越容易拒绝假设(Otis et al., 1978)。4)平均捕获率(

研究区内东北豹种群估计密度存在较大的波动[0.12~0.88只·(100 km2)-1],一方面是因为猎物丰富度等环境因子的变化导致的种群数量的实际变化,另一方面则是因为监测区域有限,样本量小以及违反闭合种群假设引起的种群密度估计误差。计算相机有效监测面积时,需要在布设相机外延增加相当于动物活动半径的缓冲区。Karanth(1998)采用监测期间动物平均最大移动距离(mean maximum distance moved,MMDM)的一半作为活动半径的替代指标。Maffei等(2008)研究结果表明,相机覆盖区域面积低于动物活动家域3~4倍时,1/2 MMDM显著低于动物活动半径,而小样本数据会增加这种偏差。对于东北豹这种活动面积较大的动物,基于相机监测获得的1/2 MMDM也很难与动物实际活动半径相吻合(Williams et al., 2002)。因此,根据Salmanova无线电遥测研究结果[雄性家域(316±114) km2,雌性家域(128±52) km2],本研究采用了东北豹平均家域的半径8 km作为缓冲区的大小。监测面积小的另一个问题是由于监测区覆盖了很多动物家域的边缘,单位面积内记录动物个体增多导致密度评估偏高(Maffei et al., 2008)。如果监测区仅覆盖动物活动区域的一小部分,会造成“拍摄羞怯反应”比例的上升,产生违背闭合种群假设的干扰,从而造成种群密度评估结果偏高。对于小样本种群,“拍摄羞怯反应”还会导致

东北豹分布格局在时空上均表现出明显的异质性。动物分布概率密度可以反映生境适宜度,东北豹分布格局受海拔等地理因素的影响,且会随猎物丰富度的状况而变化。在种群数量低的情况下,CAPTURE闭合种群检验效力并不强,检验结果总体偏低。M\-h假设是进行东北豹种群数量评估的适宜模型,动物的捕获率在拍摄前后以及不同监测时段无差异。在相机布设面积和种群数量较小的情况下,“拍摄羞怯反应”会导致种群密度评估结果偏高。

蒋劲松, 孔维尧. 2015. 长白山区东北虎、东北豹相机监测. 长春: 吉林科学技术出版社, 80-111. (Jiang J S, Kong W Y. 2015. Surveillance of northeast tiger and northeast leopard in Changbai Mountain area. Changchun: Jilin Science and Technology Press, 80-111. [in Chinese]) |

孔维尧. 2017.东北虎关键分布区有蹄类种群调查. WWF项目报告(No.10000766). (Kong W Y. 2017. Survey of hoofed population in the key area of northeast tiger. WWF project report (unpublished) [in Chinese]) |

孔维尧, 郎建民, 孙权, 等. 2017. 吉林省老爷岭南部东北豹雪地调查. 四川动物, 36(2): 239-240. (Kong W Y, Lang J M, Sun Q, et al. 2017. Investigation on the snow land of northeast leopard in the south of Laoyeling, Jilin Province. Sichuan Animal, 36(2): 239-240. [in Chinese]) |

李佳, 刘芳, 李迪强, 等. 2017. 基于红外相机监测分析的红腹角雉日活动节律. 林业科学, 53(7): 170-176. (Li J, Liu F, Li D Q, et al. 2017. Daily activity rhythm of red-bellied pheasant based on infrared camera monitoring analysis. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 53(7): 170-176. [in Chinese]) |

马鸣, 徐峰, 吴逸群, 等. 2006. 利用自动照相术获得天山雪豹拍摄率与个体数量. 动物学报, 52(4): 788-793. (Ma M, Xu F, Wu Y Q, et al. 2006. The photographic rate and individual number of snow leopard in Tianshan Mountains were obtained by automatic photography. Journal of Zoology, 52(4): 788-793. [in Chinese]) |

张桂铭, 朱阿兴, 杨胜天, 等. 2013. 基于核密度估计的动物生境适宜度制图方法. 生态学报, 33(23): 7590-7600. (Zhang G M, Zhu A X, Yang S T, et al. 2013. Animal habitat suitability mapping based on nuclear density estimation. Journal of Ecology, 33(23): 7590-7600. [in Chinese]) |

Abramov V K, Pikunov D G. 1974. Leopards in the far east of the USSR and their protection. Bulletin of the Moscow Society of Natural Scientists, Biology Branch, 79(2): 5-15. |

Aramilev V V, Fomenko P V. 2000. Simultaneous survey of Far Eastern leopards and Amur tigers in southwest Primorski Krai, Winter 2000. Final report to WCS and WWF.

|

Di Bitetti M S, Paviolo A, De Angelo C. 2006. Density, habitat use and activity patterns of ocelots (Leopardus pardalis) in the Atlantic Forest of Misiones, Argentina. Journal of Zoology, 270(1): 153-163. |

Dillon A, Kelly M J. 2007. Ocelot Leopardus pardalis in Belize: the impact of trap spacing and distance moved on density estimates. Oryx, 41(4): 469-477. DOI:10.1017/S0030605307000518 |

Gavashelishvili A, Lukarevskiy V. 2008. Modeling the habitat requirements of leopard Panthera pardus in west and central Asia. J Appl Ecol, 45(2): 579-588. DOI:10.1111/jpe.2008.45.issue-2 |

Harmsen B J. 2006. The use of camera traps for estimating abundance and studying the ecology of jaguars (Panthera onca). PhD. Dissertation, University of Outhampton, United Kingdom.

|

Hawthorne L B. [2016-07-12]. Geospatial Modelling Environment, version 0.7.3. http://www.spatialecology.com/gme.

|

Hebblewhite M, Miquelle D G, Murzin A A, et al. 2011. Predicting potential habitat and population size for reintroduction of the Far Eastern leopards in the Russian Far East. Biological Conservation, 144(10): 2403-2413. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.03.020 |

Jackson P, Nowell K. [2012-11-05]. Panthera pardus ssp. orientalis. IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. http://www.iucnredlist.org.

|

Jiang G, Qi J, Wang G, et al. 2015. New hope for the survival of the Amur leopard in China. Scientific Reports, 5: 15475. DOI:10.1038/srep15475 |

Karanth K U. 1995. Estimating tiger Panthera tigris populations from camera-trap data using capture-recapture models. Biological Conservation, 71(3): 333-338. DOI:10.1016/0006-3207(94)00057-W |

Karanth K U, Nichols J D. 1998. Estimation of tiger densities in India using photographic captures and recaptures. Ecology, 79(8): 2852-2862. DOI:10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[2852:EOTDII]2.0.CO;2 |

Kawanishi K, Sunquist M E. 2004. Conservation status of tigers in a primary rainforest of Peninsular Malaysia. Biological Conservation, 120(3): 329-344. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2004.03.005 |

Kelly M J, Noss A J, Di Bitetti M S, et al. 2008. Estimating puma densities from camera trapping across three study sites: Bolivia, Argentina, and Belize. Journal of Mammalogy, 89(2): 408-418. DOI:10.1644/06-MAMM-A-424R.1 |

Kostyria A V, Skorodelov A S, Miquelle D G, et al. 2003. Results of camera trap survey of far eastern leopard population in southwest Primorski Krai, Winter 2002-2003. Report of the Wildlife Conservation Society and Institute of Sustainable Use of Nature Resources. Vladivostok. [In Russian]

|

Maffei L, Cuéllar E, Noss A. 2004. One thousand jaguars (Panthera onca) in Bolivia's Chaco?camera trapping in the Kaa-Iya National Park. Journal of Zoology, 262(3): 295-304. DOI:10.1017/S0952836903004655 |

Maffei L, Noss A J. 2008. How small is too small? Camera trap survey areas and density estimates for ocelots in the Bolivian Chaco. Biotropica, 40(1): 71-75. |

Matiukhina D S, Vitkalova A V, Rybin A N, et al. 2016. Camera-trap monitoring of Amur Tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) in southwest Primorsky Krai, 2013-2016: preliminary results. Nature Conservation Research, 1(3): 36-43. |

Miquelle D G, Rozhnov V V, Ermoshin V, et al. 2015. Identifying ecological corridors for Amur tigers (Panthera tigris altaica) and Amur leopards (Panthera pardus orientalis). Integrative Zoology, 10(4): 389-402. |

Nowell K, Jackson P. 1996. Wild cats: status survey and conservation action plan (Vol. 382). Gland: IUCN.

|

O'Brien T G, Kinnaird M F, Wbisono H T. 2003. Crouching tigers, hidden prey: Sumatran tiger and prey populations in a tropical forest landscape. Animal Conservation, 6(2): 131-139. DOI:10.1017/S1367943003003172 |

O'Connell A F, Nichols J D, Karanth K U. 2011. Camera Traps in Animal Ecology: Methods and Analyses. Springer, New York.

|

Otis D L, Burnham K P, White G C, et al. 1978. Statistical inference from capture data on closed animal populations. Wildlife Monographs, (62): 3-135.

|

Pikunov D G, Abramov V K, Korkishko V G, et al. 2000."Sweep" survey of far eastern leopards and Amur tigers. A Survey of Far Eastern Leopards and Amur Tigers in Southwest Primorski Krai, in 2000. Final report to WCS and WWF.

|

Pikunov D G, Aramilev V V, Fomenko P V, et al. 1997. Leopard Numbers and its Habitat Structure in the Russian Far East. Final Report to Hornocker Wildlife Institute.

|

Pikunov D G, Korkishko V G. 1985. Present distribution and numbers of leopards (Panthera pardus) in the Far East USSR. Zoology Journal, 64: 897-905. |

Pikunov D G, Miquelle D G, Abramov V K, et al. 2003. Results of population surveys of Leopards (Panthera pardus orientalis) and Tigers (Panthera tigris altaica) in Southwest Primorski Krai, Russian Far East. Final Report to WCS and WWF.

|

Pikunov D G, Seredkin I V, Aramilev V V, et al. 2009. Numbers of Far Eastern Leopards (Panthera pardus orientalis) and Amur Tigers (Panthera tigris altaica) in Southwest Primorski Krai, Russian Far East, 2007. Dalnauka, Vladivostok.

|

Qi J, Shi Q, Wang G, et al. 2015. Spatial distribution drivers of Amur leopard density in northeast China. Biological Conservation, 191(11): 258-265. |

Rexstad E, Burnham K P. 1991. User's guide for interactive program CAPTURE. Colorador. Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit.

|

Salmanova E. 2012. Amur leopard home range. Student Conference on Conservation Science. UK, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 42.

|

Simcharoen S, Pattanavibool A, Karanth K U, et al. 2007. How many tigers Panthera tigris are there in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand? An estimate using photographic capture-recapture sampling. Oryx, 41(4): 447-453. DOI:10.1017/S0030605307414107 |

Soisalo M K, Cavalcanti S M. 2006. Estimating the density of a jaguar population in the Brazilian Pantanal using camera-traps and capture-recapture sampling in combination with GPS radio-telemetry. Biological Conservation, 129(4): 487-496. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.11.023 |

Soutyrina S V, Rybin A N, Miquelle D G. 2012. Recommendations for camera trap surveys of large felids in the Russian Far East.WCS Russia program Vladivostok, Primorsky Krai, Russia.

|

Sugimoto T, Aramilev V V, Kerley L, et al. 2014. Noninvasive genetic analyses for estimating population size and genetic diversity of the remaining Far Eastern leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) population. Conservation Genetics, 15(3): 521-532. DOI:10.1007/s10592-013-0558-8 |

Sugimoto T, Aramilev V V, Nagata J, et al. 2016. Winter food habits of sympatric carnivores, Amur tigers and Far Eastern leopards, in the Russian Far East. Mammalian Biology, 81(2): 214-218. DOI:10.1016/j.mambio.2015.12.002 |

Sulikhan N S, Gilbert M, Blidchenko E Y, et al. 2018. Canine distemper virus in a wild Far Eastern Leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis). Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 54(1): 170-174. DOI:10.7589/2017-03-065 |

Trolle M, Kéry M. 2003. Estimation of ocelot density in the Pantanal using capture-recapture analysis of camera-trapping data. Journal of Mammalogy, 84(2): 607-614. DOI:10.1644/1545-1542(2003)084<0607:EOODIT>2.0.CO;2 |

Uphyrkina O, Miquelle D, Quigley Driscoll C, et al. 2002. Conservation genetics of the Far Eastern Leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis). The Journal of Heredity, 93(5): 304-311. |

Vitkalova A V, Shevtsova E I. 2016. A complex approach to study the Amur leopard using camera traps in protected areas in the southwest of Primorsky Krai (Russian Far East). Nature Conservation Research, 1(3): 53-58. |

Wang T, Feng L, Mou P, et al. 2016. Amur tigers and leopards returning to China: direct evidence and a landscape conservation plan. Landscape Ecology, 31(3): 491-503. DOI:10.1007/s10980-015-0278-1 |

Wang S W, Macdonald D W. 2009. The use of camera traps for estimating tiger and leopard populations in the high altitude mountains of Bhutan. Biological Conservation, 142(3): 606-613. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.11.023 |

White G C, Anderson D R, Burnham K P, et al. 1982. Capture-recapture and removal methods for sampling closed populations. Los Alamos National Laboratory Technical Report Number LA-8787-NERP, Los Alamos, NM.

|

Williams B K, Nichols J D, Conroy M J. 2002. Analysis and Management of Animal Populations. Boston: Academic Press.

|

Yang S H, Jiang J S, Wu Z G, et al. 1998. Report on the Sino-Russian Joint Survey of Far Eastern Leopards and Siberian Tigers and their habitat in the Sino-Russian boundary area, eastern Jilin Province, China, Winter 1998. A Final Report to the UNDP and the Wildlife Conservation Society.

|

Zhang L, Cheng Y C, Feng L M, et al. [2018-08-14]. Abundance and occupancy of Leopard and their prey in Wangqing Leopard Reserve. China 99th ESA Annual Meeting (August 10 -15, 2014). https://eco.confex.com/eco/2014/webprogram/Paper.

|

2019, Vol. 55

2019, Vol. 55