文章信息

- 彭向永, 程运河, 李振坚, 于永畅, 邹竣竹, 孙振元

- Peng Xiangyong, Cheng Yunhe, Li Zhenjian, Yu Yongchang, Zou Junzhu, Sun Zhenyuan

- 蒿柳成花过程中内源激素和多胺含量变化特征

- Variations of Endogenous Hormones and Polymines during Flowering Process in Male and Female Salix viminalis

- 林业科学, 2018, 54(8): 39-47.

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2018, 54(8): 39-47.

- DOI: 10.11707/j.1001-7488.20180805

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2017-05-18

- 修回日期:2017-07-29

-

作者相关文章

2. 曲阜师范大学生命科学学院 曲阜 273165

2. School of Life Science, Qufu Normal University Qufu 273165

高等植物从营养生长向生殖生长的转变过程是多种因素共同作用的结果(Andres et al., 2012),其中激素及多胺发挥了重要的调控作用(Applewhite et al., 2000; Davis, 2009)。如细胞分裂素(CTK)和脱落酸(ABA)可调控植物顶端分生组织的生长发育,促进从营养生长向开花转变而诱导花芽分化(Gordon et al., 2009; Xing et al., 2015),赤霉素(GA)通过下调FT基因表达抑制多年生木本植物的花芽分化(Nakagawa et al., 2012)。植物成花与多种激素相关,但在不同发育阶段内激素含量及比例具有显著差异(Chandler, 2011)。橄榄(Olea europaea)小年树的侧芽中玉米素(ZT)含量在中果皮硬化期显著积累(Andreini et al., 2008),ABA含量在成花诱导关键期达到峰值(朱振家, 2015);有花芽分化的光皮梾木(Cornus wilsoniana)ABA和玉米素核苷(ZR)含量呈先逐渐升高再降低的变化趋势(何见等, 2009);枇杷(Eriobotrya japonica)的ABA含量在成花诱导期呈上升趋势,而GA3含量则减少(刘宗莉等, 2007);温州蜜桔(Citrus atsuma)的GA含量在整个花芽诱导期间呈下降趋势,在花发端时期降到最低,并且在以后的花器官发育中一直保持较低水平(张上隆等, 1990);李(Prunus salicina)花芽生理分化期和花原基分化期腐胺(Put)和精胺(Spm)含量最高,随后在花器原始体的形成期间其含量逐渐下降(钟晓红, 1990)。

与雌雄同花植物相比,雌雄异花/异株植物内源物质含量还与性别表型密切相关。花芽分化期的芦笋(Asparagus officinalis)、山靛(Mercurialis annua)雄花芽中生长素(IAA)含量均显著高于雌花(Rossi et al., 1990);不同发育阶段的银杏(Ginkgo biloba)雌、雄花芽性别间IAA含量差异显著,而GA、ABA、ZT、异戊烯基腺嘌呤类(iPAs)及激素比值变化基本一致(张万萍等, 2004;罗平源等, 2006);黄瓜(Cucumis sativus)在形成第一雄花时,GA处于峰值,而形成第一雌花时则显著降低。

蒿柳(Salix viminalis)为杨柳科(Saliaceae)柳属灌木,适应性强、易繁殖、生长速度快,在能源林建设、重金属修复、园林绿化等方面具有广阔的应用前景(Zhai et al., 2016)。蒿柳幼龄期极短,扦插苗当年形成花芽,实生苗2年开花,是研究雌雄异株木本植物的理想材料,目前对蒿柳成花诱导与花芽分化期间内源激素变化尚无系统报道。本研究以雌、雄蒿柳的1年生枝条茎尖为材料,研究营养生长期、花芽生理分化期和花芽形态分化期内源激素和多胺含量动态变化,分析激素和多胺对雌、雄蒿柳成花和性别表型的影响,为分析雌雄异株植物花器官形成及性别决定机制,并为人工调控花器官形成及性别分化提供理论依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 试验材料蒿柳生长地为内蒙古赤峰市巴林右旗赛罕乌拉国家自然保护区荣升十八景区的大海清河流域(44°14′48″N,118°20′17″E),海拔1 100 m,保护区属中温带半湿润温寒气候区,年日照时数为3 000 h,年均气温20 ℃,有效积温1 800 ℃,降水量400 mm,无霜期100天左右,土壤主要以灰色森林土和棕壤土为主,取材地为季节性河流湿地蒿柳、筐柳(Salix linearistipularis)天然混交的灌木丛林。选取树龄15~20年,同一丛内既有雌株又有雄株的蒿柳灌木丛,分别标记树干胸径一致的1个雄株主干,1个雌株主干,共标记3丛灌木的6株主干(雌、雄各3个重复)。于盛花后30天(2016年5月25日)、50天(2016年6月15日)及95天(2016年8月1日)取样,分别代表营养生长期、花芽生理分化期和花芽形态分化期,取雌、雄植株1年生枝条的2.0~3.0 cm顶端部分,剥去顶端幼嫩叶片,液氮速冻后,-80 ℃保存备用。

1.2 试验方法 1.2.1 内源激素及多胺提取参考Pan等(2008, 2010)的方法,略有改动。取出采集好的植物材料,加液氮研磨,取研磨好的粉末0.5~1.0 g装入10 mL离心管中,加入5 mL含有30 mg·L-1二乙基二硫代氨基甲酸钠的80%预冷甲醇,4 ℃下浸提24 h后,将130 000 r·min-1,4 ℃,离心5 min,转移上清液,残渣再加入2 mL浸提液,同样条件下离心10 min,合并上清液,用氮吹仪将离心管中的混合液体浓缩至2 mL左右,0.45 μm滤膜(Waters,Milford,MA,USA)过滤,滤液置于-20 ℃冰箱中保存,待测。

1.2.2 内源激素含量测定利用高效液相色谱-四级杆离子阱串联质谱仪(HPLC-MS/MS Q-TRAP,API 3200 Q-TRAP liquid mass combination,AB Company,USA)测定(Wen et al. 2016)。测定参数为,色谱柱:MSLab HP-C18 (150 mm×4.6 mm 5μm),柱温:50 ℃,流速:1 mL·min-1,流动相A为水,B为乙腈,进样量10 μL。质谱条件为,离子源:-ESI电喷雾离子源负离子方式,扫描方式:MRM多反应监测,气帘气:20 psi(CUR),碰撞气:Medium(CAD),喷雾电压:-4 000 V(IS),雾化温度:400 ℃(TEM),雾化气:55 psi(GS1),辅助气:60 psi(GS2),去族电压:(DP),射入电压:-10(EP),碰撞能量:(CE),碰撞室射出电压:-2.0(CXP)。

1.2.3 多胺(PAs)含量测定多胺含量测定方法同激素,略有改动,即柱温:30 ℃,离子源:+ESI电喷雾离子源正离子,喷雾电压:-3 000 V(IS),雾化温度:500 ℃(TEM),射入电压:+10(EP),碰撞室射出电压:+2.0(CXP)。

1.3 数据分析采用SPSS19.5分析试验数据,ANOVA进行均值间的差异性比较,LSD法进行多重比较,显著性水平设定为0.05,利用SigmaPlot 12.5绘图。

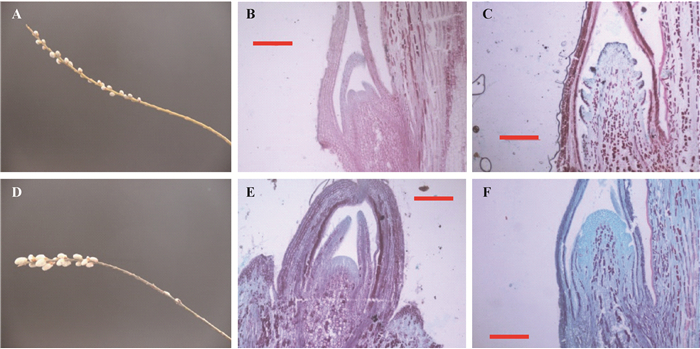

2 结果与分析 2.1 雌、雄蒿柳花芽分化阶段的划分蒿柳新梢生长一般从4月下旬的盛花后期开始,至8月下旬封顶停长,共110天左右,雌、雄蒿柳当年生枝条的叶芽多分布在中下部,而花芽均着生在枝条的中上部(图 1A,1D)。枝条顶部 < 0.5 mm芽的组织切片结果表明,当年生枝条在盛花后的0~40天(营养生长期,S1)内进行营养生长,形成的芽瘦小干瘪,上部窄,下部宽,顶端分生组织部位呈圆尖状,均为叶芽(图 1B,1C),盛花后40~70天(花芽生理分化期,S2)由营养生长向生殖生长过渡期,而盛花后70~110天形成的芽饱满肥大,顶端分生组织扁平,细胞数多,核小密集,且花序轴下陷,出现明显的小花原基,无小叶片包裹,此时正进行花器官的形态分化(花芽形态分化期,S3)(图 1E,1F)。

|

图 1 雌、雄蒿柳花芽着生部位及叶芽和花芽的组织形态结构 Figure 1 Flower buds distribution on the annual shootsand morphological of vegetative and floral buds in male and female S. viminalis A,D:雌、雄蒿柳当年生枝条上花芽分布;B,E:雌、雄蒿柳叶芽;C,F:雌、雄蒿柳花芽。标尺为200 μm。 A, D: flower buds distribution on the annual shoots. B, E: vegetative buds. C, F: floral buds, in female and male S. viminalis, respectively. Bar represented 200 μm. |

由图 2可知,雌、雄蒿柳成花过程中,ABA、ZT和IAA含量均表现为先上升后下降趋势。雌、雄蒿柳ABA含量从S1到S2分别显著升高324%和131%,从S2到S3又分别下降86.40%和52.18%(P < 0.05);雌、雄蒿柳S2的ZT含量比S1分别升高75.87%和57.47%(P < 0.05),S3比S2又分别下降了45.01%和19.36%,雌株和雄株S2期茎尖中的ZT含量与S1和S3均达到显著差异水平(P < 0.05)。从S1到S2,雌蒿柳IAA含量上升25.30%,但差异不显著(P>0.05);雄蒿柳IAA含量显著上升了47.95%(P < 0.05),从S2到S3,雌、雄蒿柳IAA则分别下降42.40%和34.49%(P < 0.05)。成花过程中,雌、雄蒿柳GA3含量均呈下降趋势,从S1到S2,雌蒿柳GA3含量降低18.86% (P>0.05),雄蒿柳则下降42.66%(P < 0.05),从S2到S3,雌、雄蒿柳GA3含量分别降低57.89%和60.84%(P < 0.05)。结果表明,高水平的ABA、ZT和IAA含量可促进雌、雄蒿柳成花启动,较低水平的ABA、ZT和IAA含量则利于花芽形态分化;高水平GA3含量可保持蒿柳的营养生长状态,茎尖中的GA3含量的下降一定水平后,可启动花芽生理分化,而花芽的形态分化则需要GA3含量进一步降低。

|

图 2 雌、雄蒿柳成花过程中内源激素含量变化 Figure 2 Hormone contents during flowering process in male and female S. viminalis |

成花过程中,雌、雄蒿柳茎尖的激素含量变化趋势基本一致,但在有些发育阶段却表现出显著的性别间差异。蒿柳茎尖中的ABA含量在S2和S3均表现出显著的性别差异,S2期的雌株茎尖中ABA含量是雄株的1.97倍,但从S2到S3雌株ABA含量下降幅度大于雄株,S3期雌株茎尖中ABA含量反而比雄株低44.00%(P < 0.05)。ZT含量在S1和S3均无性别差异,但在S2期,雌株ZT含量比雄株高31.31%,表现出显著的性别差异(P < 0.05)。在S1和S2期,雌株茎尖中的IAA含量比雄株分别高48.13%和25.45,均表现出显著的性别差异(P < 0.05)。成花过程中,虽然雌、雄蒿柳性别间的GA3含量并未表现出显著差异,但在S1和S2期也差别较大。S2期(花芽生理分化期)雌、雄蒿柳ABA、ZT和IAA含量均具有显著的性别差异,且雌株高于雄株,表明激素含量差异与蒿柳性别表型分化密切相关。

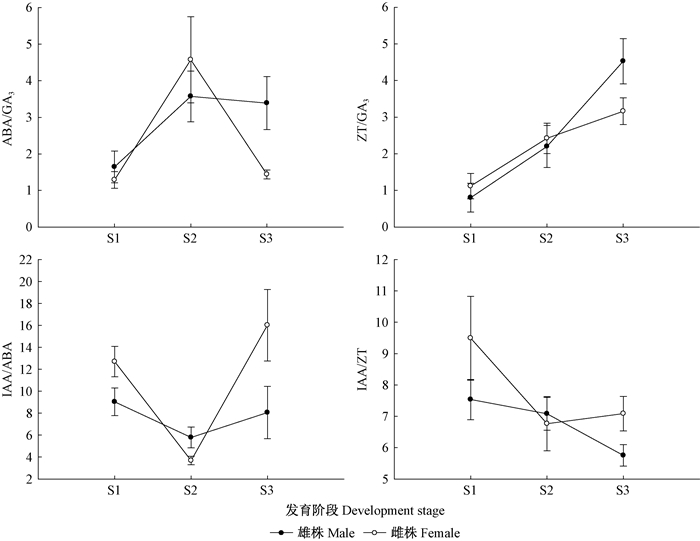

2.2 雌、雄蒿柳成花过程中激素比值由图 3可知,从S1到S2,雌、雄蒿柳ABA/GA3比值均显著升高;从S2到S3,雌株ABA/GA3比值显著下降(P < 0.05),而雄株仅表现为小幅降低,差异不显著。从S1到S3,雌、雄蒿柳的ZT/GA3比值均持续升高,雄株3个发育阶段的比值间差异显著,而雌株仅S2的比值显著高于S1(P < 0.05)。从S1到S2,雌、雄蒿柳的IAA/ABA比值均显著下降;从S2到S3,雌株IAA/ABA比值显著升高(P < 0.05),虽然雄株的比值也略微升高,但未达到差异显著水平。蒿柳雌株和雄株的IAA/ZT比值从S1到S2均下降,但仅雌蒿柳中的比值差异显著;从S2到S3,雄株IAA/ZT的比值持续降低,而雌株IAA/ZT的比值却略微升高。雌、雄蒿柳成花的不同发育阶段激素比值变化,说明高的ABA/GA3和ZT/GA3比值,低的IAA/ABA和IAA/ZT比值均可促进雌、雄蒿柳花芽分化。

|

图 3 雌、雄蒿柳成花过程中激素比值的变化 Figure 3 Ratios of hormones during flowering process in male and female S. viminalis |

成花过程中,雌、雄蒿柳茎尖的激素比值变化趋势基本一致,但一些发育阶段表现出显著性别间差异。雌、雄蒿柳ABA/GA3、ZT/GA3、IAA/ABA和IAA/ZT比值在S3期均具有显著的性别间差异;其中,雄蒿柳ABA/GA3和ZT/GA3比值显著高于雌株,而雌蒿柳IAA/ABA和IAA/ZT比值显著高于雄株(P < 0.05),说明性别间激素比值差异与花芽形态分化和花器官如雌、雄蕊形成等相关。另外,雌蒿柳S1期的IAA/ABA比值高于雄株,S2期则相反,但2个时期IAA/ABA比值均达到显著差异水平(P < 0.05),说明IAA/ABA比值可能与蒿柳性别表型的分化相关。

2.3 雌、雄蒿柳成花过程中PAs含量由图 4可知,雌、雄蒿柳茎尖中PAs主要是Put,而Spm和Spd(亚精胺)含量较少,成花过程中茎尖Put、Spm、Spd含量均呈上升趋势。从S1到S2,雌、雄蒿柳Put分别升高64.61%和119.90%,从S2到S3又分别上升78.54%和86.89%,均达到了差异极显著水平(P≤0.01)。从S1到S2,Spm分别上升了157.73%和224.18%,从S2到S3分别又上升了100.58%和173.81%,且不同发育阶段间Spm含量均达到了显著差异水平(P < 0.05)。Spd含量的变化趋势与Spm一致,且不同发育阶段间Spd含量均达到了显著差异水平(P < 0.05)。结果表明,蒿柳花芽生理分化期茎尖中的PAs含量升高,有利于花芽分化的启动,花芽形态分化期可能需要更高水平的PAs含量。

|

图 4 雌、雄蒿柳成花过程中PAs含量变化 Figure 4 PAs contents during flowering process in male and female S. viminalis |

在S1期,蒿柳雌株茎尖中的Put、Spd和Spm含量均高于雄株,从S1到S2,雄蒿柳中Put上升速度大于雌株,S2期的雄蒿柳Put含量高于雌株,而雌株Spd和Spm含量仍低于雄株,从S2到S3,雄蒿柳中Put、Spd和Spm含量升高速度均高于雌株,S3期的雄蒿柳3种多胺含量均高于雌株。雌、雄蒿柳不同发育阶段及性别间PAs含量均有差异,但除了S1和S2期的Spd含量表现出显著的性别间差异,其他均差异不显著。结果表明,高水平PAs含量对雌、雄蒿柳花芽分化启动和花器官形态建成具有促进作用,但对花器官性别表型差异分化无明显作用。

3 讨论植物激素和多胺在成花诱导和阶段转变过程中具有重要的调控作用(Davis, 2009; Sood et al., 2004),但在木本植物特别是在雌雄异株木本植物中的研究仍少有报道。细胞分裂素可调控细胞分裂、营养生长向开花转变、花芽诱导等过程(Amasino, 2010)。本研究表明,从营养生长向花芽生理分化期转变的雌、雄蒿柳茎尖中ZT含量快速升高,至花芽形态分化期又急剧下降,说明ZT对雌、雄蒿柳成花第一步即花芽诱导具有正相关作用。已有研究表明,细胞分裂素可通过促进FT的同源基因TSF的表达来诱导植物成花(D’Aloia et al. 2011),SOC1基因位于FT下游整合多条开花途径来调控开花,其在成花诱导期表达量高,而花芽分化期表达量低(周华, 2015)。细胞分裂素不仅可诱导茎尖分生组织中的SOC1基因表达而促进开花(Lee et al., 2010),其同源基因如AGL19、AGL20和AGL42也能响应高水平的细胞分裂素(Xing et al., 2015)。雌、雄蒿柳中ZT含量的变化呈现出与相关基因表达具有同步性,其分子调控机制有待进一步深入研究。

ABA在植物生长发育的多个阶段均发挥重要作用,如种子萌发、阶段转变以及环境胁迫响应等(Tsai et al., 2014)。在花诱导和分化起始阶段,高水平的ABA可促进橄榄花芽形成(Ulger et al., 2004),银杏雌花芽从生理分化到形态分化,ABA含量先升高后下降并维持低水平(史继孔等, 1999)。雌、雄蒿柳茎尖中ABA含量也表现为先升高后下降的变化规律。ABA信号可以通过影响生物节律调控植物开花及发育阶段转变(De et al., 2010),一些生物节律相关基因如TOC1、ZTL、GI、PRR5等的表达模式与ABA含量变化一致(Xing et al., 2015)。另外,外源ABA可促进AP1表达而诱导花芽分化启动(Cui et al., 2013)。推测生物钟依赖的ABA信号途径可能参与调控雌、雄蒿柳的花芽诱导过程。

赤霉素可活化SOC1基因,促进拟南芥(Arabidopsis thaliana)、水稻(Oryza sativa)等1年生植物的成花(Fukazawa et al., 2014; Fu et al., 2001),但在一些多年生木本植物上却表现抑制成花的作用(Wilkie et al., 2008)。本研究发现,从营养生长向生理分化转变的雌、雄蒿柳的GA3含量均快速下降。SPY基因是GA信号的负调控因子,同时也是细胞分裂素信号的正调控因子(Greenboim-Wainberg et al., 2005),SPY基因可以与GI相互作用参与光信号调控的成花过程(Tseng et al., 2004);GA和细胞分裂素在调控顶端分生组织分化和花诱导启动过程中具有拮抗作用,还可能是因为细胞分裂素能够提高KNOX在顶端分生组织的表达水平而直接抑制GA合成途径基因GA20ox,导致GA含量下降(Sakamoto et al., 2001)。此外,外源施用GA通过调控FT的表达抑制多年生木本植物花芽分化(Nakagawa et al., 2012)。GA含量对雌、雄蒿柳的花芽分化是否同样具有负向调控作用或如何调控有待进一步研究。

激素在植物花芽分化过程中具有重要调控作用,但植物是一个有机整体,仅仅分析单一激素的调控作用不全面;植物花芽形成是多种激素以一定的比例在时间(花器官诱导与发育时期)和空间(激素作用的部位)的多维度调控的结果(Chandler, 2011)。超表达蓝莓(Vaccinium craspedotum)FT基因发现5类植物激素共110个相关的基因差异表达,并表现早花表型(Gao et al., 2016);番茄(Lycopersicon esculentum)APETALA3基因突变,可导致赤霉素、生长素、细胞分裂素、水杨酸、精胺和酪胺浓度下降,而茉莉酸和脱落酸浓度升高,这种新建立的平衡可诱导开启成花相关基因,合成特殊的mRNA和蛋白质而调节成花(Quinet et al., 2015)。李子水平枝条花芽少于直立枝条,GA生物合成基因PslGA 3 ox的表达水平低于直立的对照树,而PslGA3ox的低表达水平与低活性GA1、GA3、GA4和IAA相关(Chutinanthakun et al., 2015)。另外,任何增加CTK含量或降低GA含量的措施均能影响苹果(Malus pumila)CTK/GA的动态平衡,提高果树的花芽分化(周学明等,1988)。蒿柳茎尖从营养生长向生殖生长转变过程中的ZT/GA3比值均持续升高,也验证了这一点。雌、雄蒿柳茎尖中IAA/ZT持续下降,因为6-BA处理可间接打破抑制MdTFL1表达的CTK/IAA比值,导致AFL1在花起始时更高的转录水平,并改变芽组分和生长特性,最终促进花芽的分化和发育(Li et al., 2016)。

多胺对植物的生长发育具有广谱的调控作用(Martin-Tanguy, 2001),植物体内多以游离的阳离子形式存在,也可与小分子如酚酸以及各种大分子共轭;作为第二信使影响果树的生长、花芽分化、开花、花粉管生长、结果等过程(Sood et al., 2004; Falasca et al., 2010)。精氨酸(Arg)是合成PAs的前体,花芽生理分化期叶片中的Arg含量急剧上升(崔凤芝等, 1996);外源Put、Spd及Spm不仅促进苹果花芽的形成而且花芽数量增加(Costa et al., 1986; Lovatt, 1990);玫瑰(Rosa rugosa)花芽发育的早期花瓣中含有高水平游离Put和Spd(Sood et al., 2004),而过表达多胺合酶SPDM和SPDS发现可正调控FT而促进龙胆(Gentiana triflora)提早成花(Imamura et al., 2015)。本研究发现,雌、雄蒿柳茎尖中的Put含量最多,在花芽生理分化期尖中的Put含量急剧升高,而Spd和Spm含量虽然少,但变化趋势与Put一致。由此推测雌、雄蒿柳茎尖中的Put、Spd和Spm促进,其花芽的形成。

雌雄异株植物的性别差异大多是非组成型的,基因表达、内源物质含量仅在发育的某些阶段具有显著的差异(汪俏梅等, 1997)。本研究也发现,雌、雄蒿柳内源激素和多胺的变化趋势几乎一致,但其含量仅在发育的某些阶段具有显著的性别差异。激素不仅可以调控植物的生长发育,而且也与植物的性别决定相关,外源生长素可诱导山靛雌株节上产生雄花,细胞分裂素可在雄株上诱导出雌花,其性别受到3个基因控制,2个互补基因A和B决定雄性,强雄性由显性B基因数量决定,单独的显性A或显性B基因可诱导雌性(Durand et al., 1991)。喷施外源激素GA、IAA、ABA可以诱导水杉(Metasequoia glyptostroboides)雌、雄花芽分化,童期缩短(Zhao et al., 2015)。RPN参与了生长素信号转导,拟南芥rpn10可下调细胞周期基因CDKA组成型表达而抑制雄蕊生长,减少雄配子体数量(Smalle et al., 2003);an1、d1、d3、d5突变体影响玉米(Zea mays)赤霉素的合成,而缺乏GA的玉米突变体雌花序不经历花芽发育抑制而形成完整的小花(Fujioka et al., 1988);酸模(Rumex acetosa)雄花序中含有较高水平的GA18和GA29,而雌性具有较高水平的GA53和GA19,这种差异可能对酸模的性别决定有作用(Stokes et al., 2003)。本研究花芽生理分化期的雌蒿柳茎尖ABA、ZT和IAA的含量均显著高于雄蒿柳,可能是调控雌、雄蒿柳花器官表型形成的重要原因。

4 结论高水平的ABA、ZT、IAA、多胺含量及ABA/GA3、ZT/GA3比值启动雌、雄蒿柳花芽生理分化,高水平的多胺、ZT/GA3、IAA/ABA有利于雌、雄蒿柳花芽的形态分化;雌、雄蒿柳在成花过程中的内源激素和多胺含量变化趋势几乎一致,但生理分化期的ABA、ZT、IAA、Spd含量及IAA/ABA比值具有显著的性别差异,可能与蒿柳的性别分化相关。

崔凤芝, 张运涛. 1996. 多胺与园艺植物生长发育的关系[J]. 河北农业大学学报, 19(3): 94-98. (Cui F Z, Zhang Y T. 1996. Polyamines in relation to growth and development of horticultural crops[J]. Journal of Agricultural University of Hebei, 19(3): 94-98. [in Chinese]) |

何见, 蒋丽娟, 李昌珠, 等. 2009. 光皮树花芽分化过程中内源激素含量变化的研究[J]. 中国野生植物资源, 28(2): 41-45. (He J, Jiang L J, Li C Z, et al. 2009. Changes of endogenous hormones, during the flower bud differentiation of Cornus wilsonian[J]. Chinese Wild Plant Resources, 28(2): 41-45. [in Chinese]) |

刘宗莉, 林顺权, 陈厚彬. 2007. 枇杷花芽和营养芽形成过程中内源激素的变化[J]. 园艺学报, 34(2): 339-344. (Liu Z L, Lin S Q, Chen H B. 2007. Time course changes of endogenous hormone levels during the floral and vegetativebuds formation in loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lind.)l[J]. Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 34(2): 339-344. [in Chinese]) |

罗平源, 史继孔, 张万萍. 2006. 银杏雌花芽分化期间内源激素、碳水化合物和矿质营养的变化[J]. 浙江农林大学学报, 23(5): 532-537. (Luo P Y, Shi J K, Zhang W P. 2006. Changes of endogenous hormones, carbohydrate and mineral nutrition during the differentiation of female flower buds of Ginkgo biloba[J]. Journal of Zhejiang A & F University, 23(5): 532-537. [in Chinese]) |

彭向永. 2017. 雌、雄蒿柳花芽分化机制及性别决定基因挖掘. 北京: 中国林业科学研究院博士论文. (Peng X Y. 2017. Mechanism of floral bud differentiation and discovery of sex determination genes in male and female Salix viminalis. Beijing: PhD thesis of Chinese Academy of Forestry. [in Chinese]) |

汪俏梅, 曾广文. 1997. 高等植物性别分化的诱导信号[J]. 植物生理学通讯, 33(2): 147-151. (Wang Q M, Zeng G W. 1997. Inducing signal of sex differentiation in higher plants[J]. Plant Physiology Communications, 33(2): 147-151. [in Chinese]) |

史继孔, 张万萍, 樊卫国, 等. 1999. 银杏雌花芽分化过程中内源激素含量的变化[J]. 园艺学报, 26(3): 194-195. (Shi J K, Zhang W P, Fan W G, et al. 1999. Changes in endogenous hormones during the differentiation of female flower bud of Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba L.)[J]. Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 26(3): 194-195. [in Chinese]) |

张上隆, 阮勇凌, 储可铭, 等. 1990. 温州蜜桔花芽分化内源玉米素和赤霉素的变化[J]. 园艺学报, 17(4): 270-274. (Zhang S L, Ruan Y L, Chu K M, et al. 1990. Changes of endogenous zeatin and gibberellic acid in Citrus satsuma during the period of flower bud formation[J]. Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 17(4): 270-274. [in Chinese]) |

张万萍, 史继孔. 2004. 银杏雄花芽分化期间内源激素、碳水化合物和矿质营养含量的变化[J]. 林业科学, 40(2): 51-54. (Zhang W P, Shi J K. 2004. Changes of endogenous hormones, carbohydrate and mineral nutritions during the differentiation of male flower buds in Ginkgo biloba[J]. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 40(2): 51-54. DOI:10.11707/j.1001-7488.20040209 [in Chinese]) |

钟晓红, 罗先实, 陈爱华. 1990. 李花芽分化与体内主要代谢产物含量的关系[J]. 湖南农业大学学报, 25(1): 31-35. (Zhong X H, Luo X S, Chen A H. 1990. A study on Nai Plum's flower bud differentiation and its major content of metabolic production[J]. Journal of Hunan Agricultural University, 25(1): 31-35. [in Chinese]) |

周华. 2015. 基于转录组比较的牡丹开花时间基因挖掘. 北京: 北京林业大学博士论文. (Zhou H. 2015. Discovery of gene associated with flowering time in tree peonies based on transciptome comparison. Beijing: PhD thesis of Beijing Forestry University. [in Chinese]) |

周学明, 马焕普, 王凤珍, 等. 1988. 不同时期苹果花芽和叶芽中内源赤霉素、脱落酸和细胞分列式活性的变化[J]. 中国农业科学, 21(3): 41-45. (Zhou X M, Ma H P, Wang F Z, et al. 1988. Variation of gibberellins, cytokinins and abscisic acid in vegetative and flower buds in various periods of apple tree[J]. Scientia Agricultura Sinica, 21(3): 41-45. [in Chinese]) |

朱振家, 姜成英, 史艳虎, 等. 2015. 油橄榄成花诱导与花芽分化期间侧芽内源激素含量变化[J]. 林业科学, 51(11): 32-39. (Zhu Z J, Jiang C Y, Shi Y H, et al. 2015. Variations of Endogenous Hormones in Lateral Buds of Olive Trees(Olea europaea) during floral induction and flower-bud differentiation[J]. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 51(11): 32-39. [in Chinese]) |

Amasino R M. 2010. Seasonal and developmental timing of flowering[J]. The Plant Journal, 61(6): 1001-1013. DOI:10.1111/tpj.2010.61.issue-6 |

Andreini L, Bartolini S, Guivarc'h A, et al. 2008. Histological and immunohistochemical studies on flower induction in the olive tree (Olea europaea L.)[J]. Plant Biology, 10(5): 588-595. DOI:10.1111/plb.2008.10.issue-5 |

Andres F, Coupland G. 2012. The genetics basis of flowering responses to seasonal cues[J]. Nature Reviews Genetics, 13(9): 627-639. DOI:10.1038/nrg3291 |

Applewhite P B, Kaur-Sawhney R, Galston A W. 2000. A role for spermidine in the bloting and flowering of Arabidopsis[J]. Physiologia Plantarum, 108(3): 314-320. DOI:10.1034/j.1399-3054.2000.108003314.x |

Chandler J W. 2011. The hormonal regulation of flower development[J]. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 30(2): 242-254. DOI:10.1007/s00344-010-9180-x |

Chutinanthakun T, Sekozawa Y, Sugaya S, et al. 2015. Effect of bending and the joint tree training system on the expression levels of GA3-, and GA2- oxidases, during flower-bud development in 'Kiyo' Japanese plum[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 193(6): 308-315. |

Costa G, Barakli R, Bagni N. 1986. Effect of putreseinon fruiting performance of apple(cv. Hi Early)[J]. Acta Horticulturae, 179(1): 355-361. |

Cui Z, Zhou B, Zhang Z, et al. 2013. Abscisic acid promotes flowering and enhance LcAP1 expression in Litchi chinensis Sonn[J]. South African Journal of Botany, 88(9): 76-79. |

D'Aloia M, Bonhomme D, Bouché F, et al. 2011. Cytokinin promotes flowering of Arabidopisis via transcriptional activation of the FT paralogue TSF[J]. The Plant Journal, 65(6): 972-979. DOI:10.1111/tpj.2011.65.issue-6 |

Davis S J. 2009. Integrating hormones into the floral-transition pathway of Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Plant Cell and Environment, 32(9): 1201-1210. DOI:10.1111/pce.2009.32.issue-9 |

De M A, Tóth R, Coupland G. 2010. Plant development goes like clockwork[J]. Trends in genetics, 26(7): 296-306. DOI:10.1016/j.tig.2010.04.003 |

Durand B, Durand R. 1991. Sex determination and reproductive organ differentiation in Mercurialis[J]. Plant Science, 80(1): 49-65. |

Falasca G, Franceschetti M, Bagni N, et al. 2010. Polyamine biosynthesis and control of the development of functional pollen in kiwifruit[J]. Plant Physiology Biochemistry, 48(7): 565-573. DOI:10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.02.013 |

Fu X, Harberd N P. 2001. Expression of Arabidopsis GAIin transgenic rice represses multiple gibberellin responses[J]. Plant Cell, 13(8): 1791-1802. DOI:10.1105/tpc.13.8.1791 |

Fukazawa J, Teramura H, Murakoshi S, et al. 2014. DELLAS function as coactivators of GAI-associated factors in regulation of gibberellin homeostasis and signaling in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Cell, 26(7): 2920-2938. DOI:10.1105/tpc.114.125690 |

Fujioka S, Yamane H, Spray C R, et al. 1988. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of gibberellins in vegetative shoots of normal, dwarf-1, dwarf-2, dwarf-3, and dwarf-5 seedlings of Zea mays L[J]. Plant Physiology, 88(4): 1367-1372. DOI:10.1104/pp.88.4.1367 |

Gao X, Walworth A E, MacKie C, et al. 2016. Overexpression of blueberry FLOWERING LOCUS T is associated with changes in the expression of phytohormone-related genes in blueberry plants[J]. Horticulture Research, 3: 16053. DOI:10.1038/hortres.2016.53 |

Gordon S P, Chickarmane V S, Ohno C, et al. 2009. Multiple feedback loops through cytokinin signaling control stem cell number within the Arabidopsis shoot meristem[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(38): 16529-16534. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0908122106 |

Greenboim-Wainberg Y, Maymon I, Borochov R, et al. 2005. Cross talk between gibberellin and cytokinin:the Arabidopsis GA response inhibitor SPINDLY plays a positive role in cytokinin signaling[J]. Plant Cell, 17(1): 92-102. DOI:10.1105/tpc.104.028472 |

Imamura T, Fujita K, Tasaki K, et al. 2015. Characterization of spermidine synthase and spermine synthase—The polyamine-synthetic enzymes that induce early flowering in Gentiana triflora[J]. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communication, 463(4): 781-786. |

Lee J, Lee I. 2010. Regulation and function of SOC1, a flowering pathway integrator[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 61(9): 2247-2254. DOI:10.1093/jxb/erq098 |

Li Y M, Zhang D, Xing L B, et al. 2016. Effect of exogenous 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA) on branch type, floral induction and initiation, and related gene expression in 'Fuji' apple (Malus domestica Borkh)[J]. Plant Growth Regulation, 79(1): 65-70. DOI:10.1007/s10725-015-0111-5 |

Lovatt C J. 1991. Stress alters ammonia and arginine metabolism//Flores H E, Arteca R N Shannon J C. Polyamines and ethylene: biochemistry, physiology, and interactions, Maryland: American Society of Plant Physiologists, 166-179.

|

Martin-Tanguy J. 2001. Metabolism and function of polyamines in plants:recent development (new approaches)[J]. Plant Growth Regul, 34(1): 135-148. DOI:10.1023/A:1013343106574 |

Nakagawa M, Honsho C, Kanzaki S, et al. 2012. Isolation and expression analysis of FLOWERING LOCUS T-like and gibberellin metabolism genes in biennial-bearing mango trees[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 139: 108-117. DOI:10.1016/j.scienta.2012.03.005 |

Pan X Q, Welti R, Wang X M. 2008. Simultaneous quantification of major phytohormones and related compounds in crude plant extracts by liquid chromatography-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Phytochemistry, 69(8): 1773-1781. DOI:10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.02.008 |

Pan X Q, Welti R, Wang X M. 2010. Quantitative analysis of major plant hormones in crude plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry[J]. Nature Protocols, 5(6): 986-992. DOI:10.1038/nprot.2010.37 |

Quinet M, Bataille G, Motyka V, et al. 2015. Hormonal regulation of floral organ development in the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L. ) mutant stamenless. Plant Organ Growth Symposium (Gent, Belgium, du 10/03/2015 au 12/03/2015).

|

Rossi G, Scaglione G, Longo C P, et al. 1990. Sexual differentiation in Asparagus officinalis L[J]. Hormonal content and peroxidase isoenzymes in female and male plants. Sexual Plant Reproduction, 3(4): 236-369. |

Sakamoto T, Kamiya N, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, et al. 2001. KNOX homeodomain protein directly suppresses the expression of a gibberellin biosynthetic gene in the tobacco shoot apical meristem[J]. Genes & Development, 15(5): 581-590. |

Smalle J, Kurepa J, Yang P, et al. 2003. The pleiotropic role of the 26S proteasome subunit RPN10 in Arabidopsis growth and development supports a substrate-specific function in abscisic acid signaling[J]. Plant Cell, 15(4): 965-980. DOI:10.1105/tpc.009217 |

Sood S, Nagar P K. 2004. Changes in endogenous polyamines during flower development in two diverse species of rose[J]. Plant Growth Regulation, 44(2): 117-123. DOI:10.1023/B:GROW.0000049413.87438.b4 |

Stokes T S, Croker S J, Hanke D E. 2003. Developing inflorescences of male and female Rumex acetosa L[J]. show differences in gibberellin content. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 22(3): 228-239. DOI:10.1007/s00344-002-0033-0 |

Tsai A Y, Gazzarrini S. 2014. Trehalose-6-phosphate and SnRK1 kinases in plant development and signaling:the emerging picture[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 5: 119. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2014.00119 |

Tseng T S, Salomé P A, Mc Clung C R, et al. 2004. SPINDLY and GIGANTEA interact and act in Arabidopsis thaliana pathways involved in light responses, flowering, and rhythms in cotyledon movements[J]. Plant Cell, 16(6): 1550-1563. DOI:10.1105/tpc.019224 |

Ulger S, Sonmez S, Karkacier M, et al. 2004. Determination of endogenous hormones, sugars and mineral nutrition levels during the induction, initiation and differentiation stage and their effects on flower formation in olive[J]. Plant Growth Regulation, 42(1): 89-95. DOI:10.1023/B:GROW.0000014897.22172.7d |

Wen X, Luo K, Xiao S, et al. 2016. Qualitative analysis of chemical constituents in traditional Chinese medicine analogous formula cheng-Qi decoctions by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry[J]. Biomedical Chromatography, 30(3): 301-311. DOI:10.1002/bmc.v30.3 |

Wilkie J D, Sedgley M, Olesen T. 2008. Regulation of floral initiation in horticulturae trees[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 59(12): 3215-3228. DOI:10.1093/jxb/ern188 |

Xing L B, Zhang D, Li Y M, et al. 2015. Transcription profiles reveal sugar and hormone signaling pathways mediating flower induction induction in apple (Malus domestica Borkh.)[J]. Plant Cell Physiology, 56(10): 2052-2068. DOI:10.1093/pcp/pcv124 |

Zhai F F, Mao J M, Liu J X, et al. 2016. Male and female subpopulations of Salix viminalis present high genetic diversity and high long-term migration rates between them[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 7: 330. |

Zhao Y, Liang H Y, Li L, et al. 2015. Digital gene expression analysis of male and female bud transition in Metasequoia reveals high activity of MADS-box transcription factors and hormone-mediated sugar pathways[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 6: 467. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2015.00467 |

2018, Vol. 54

2018, Vol. 54