文章信息

- 杨林, 邓晶晶, 郭华, 胥焘, 王传华

- Yang Lin, Deng Jingjing, Guo Hua, Xu Tao, Wang Chuanhua

- 神农架次生林原生树种与引入树种树干附生地衣多样性差异

- Divergence of Epiphytic Lichen Diversity of Native and Introduced Tree Species in the Secondary Forests of Shennongjia Mountain

- 林业科学, 2017, 53(7): 149-158.

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2017, 53(7): 149-158.

- DOI: 10.11707/j.1001-7488.20170715

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2016-03-07

- 修回日期:2017-06-21

-

作者相关文章

2. 贵州健康职业学院 铜仁 554300;

3. 山西师范大学生命科学学院 临汾 041000;

4. 三峡地区地质灾害与生态环境湖北省协同创新中心 宜昌 443002

2. Guizhou Technical College of Health Tongren 554300;

3. College of Life Sciences, Shanxi Normal University Linfen 041000;

4. Hubei Provincial Collaborative Innovation Center for Geo-Hazards and Eco-Environment in Three Gorges Area Yichang 443002

附生地衣是森林生态系统的重要成分,在维持生物多样性和养分与水分循环、指示环境质量等方面具有重要作用(刘文耀等,2006),森林附生地衣多样性及其形成机制已引起生态学家关注。目前,森林群落水平的研究认为,光照(Lange et al., 1998;Király et al., 2013)、温度(Ellis et al., 2007)、水分(Hauck et al., 2005)、矿质营养(Schmull et al., 2002)、林龄(Boudreault et al., 2008)、生境破碎化(Haig et al., 2000)、火干扰(Holt et al., 2008)及其演替阶段(Li et al., 2013)等影响地衣群落多样性。进一步研究表明,除了树木年龄(Fritz et al., 2010; Rogers et al., 2008)、树冠微生境(Fritz et al., 2010)以外,树种组成也是影响森林附生地衣多样性的重要因素(Thor et al., 2010),因此,森林演替、森林砍伐、营林等经营行为所导致的林分变化对树生地衣多样性必然产生重要影响。然而,有关树种水平附生地衣多样性差异及其形成机制的研究仅在北方针叶林(Halonen et al., 1991)、热带阔叶林(Wolseley et al., 1997)及温带森林(Leppik et al., 2008)地区开展,我国仅有李苏等(2007)对云南哀牢山地区的热带季雨林开展了相关研究。因此,在我国亚热带地区开展不同宿主树种附生地衣群落多样性研究,不仅对于全面理解全球森林群落附生地衣多样性的形成机制具有理论价值,而且也对加强我国森林地衣多样性管理具有实际意义。

神农架地处我国北亚热带与暖温带的过渡地区,在海拔420~1 800、1 800~2 600和2 600~3 100 m分布有常绿-落叶阔叶混交林、温性针叶林、落叶林和寒温性常绿针叶林林带(葛继稳等,1997)。但是,20世纪70年代至90年代末期,神农架地区约78.3%的森林被采伐或开垦为农田,并引进华山松(Pinus armandii)、日本落叶松(Larix kaempferi)、马尾松(Pinus massoniana)等用材树种营造人工林,因此,该地区现存植被主要为人工干扰后部分恢复的次生林。20世纪90年代末期至今,该地区大面积实施天然林保护工程和退耕还林工程,采伐迹地正逐步恢复为以原生树种为主的次生林,而人工林则趋于成熟并出现了因虫害而致的衰退迹象,该地区次生林的物种组成正在发生显著变化。神农架地区地衣多样性是我国地衣多样性的重要组成部分,不仅具有存在价值及用于环境监测的潜在价值(Hawksworth et al., 1970),更在川金丝猴(Rhinopithecus roxellana)种群维持中发挥了独特的支撑作用(铁军等,2010),因此,神农架地区森林物种组成变化对该地区附生地衣多样性的影响,是一个事关该地区地衣多样性保护乃至川金丝猴种群保育的重要问题。鉴于此,本研究采用样线法调查神农架地区次生林和人工林建群种树干附生地衣的群落多样性,揭示该地区次生林树干附生地衣的多样性水平、次生林建群种与人工林引进树种间的地衣多样性差异,以期为该地区附生地衣多样性保护和次生林管理提供理论支持。

1 研究区概况选择神农架林区刘家屋场(110°21′E,31°33′N)附近地区为研究区域。该地区海拔1 700 m,年均气温11.6~12.2 ℃,年降水量861 ~1 093 mm(葛继稳等,1997),拥有以巴山冷杉(Abies fargesii)、糙皮桦(Betula utilis)、枹栎(Quercus serrata)、灯台树(Bothrocaryum controversum)、锐齿槲栎(Quercus aliena var. acuteserrata)和华中樱桃(Cerasus conradinae)等为主的次生针阔混交林植被(李广良等,2012);同时,该地区还分布着一定面积的华山松(Pinus armandii)、马尾松(Pinus massoniana)和日本落叶松(Larix kaempferi)林,林龄均在20年左右。该地土壤类型为山地黄棕壤(张于光等,2014)。

2 研究方法 2.1 野外调查及地衣鉴定在以刘家屋场为中心的地区共设置5块次生林样地,各样地面积均为10 m×1 200 m。其中,在酒壶瓶和严家屋场共设置落叶阔叶林样地3块,目测郁闭度为0.8;在刘家屋场和酒壶瓶设置针阔混交林样地2块,目测郁闭度为0.7(表 1)。由于山势较陡,故采用样带法进行调查。为降低海拔差异引起的误差,每块样地在同一等高线上设置5条长200 m的样线,样线间距约50 m,构成1条海拔高差约10 m、长约1 200 m的样带。调查时,同一树种内尽可能选择胸径和立地条件基本一致的植株作为样树,其中,川鄂柳(Salix fargesii)直径9.5 cm、皂柳(Salix wallichiana)12.7 cm、细花樱桃(Cerasus pusilliflora)12.7 cm、青檀(Pteroceltis tatarinowii)19.7 cm、灯台树17.1 cm、锐齿槲栎29.2 cm、巴山冷杉21.2 cm、马尾松16.4 cm、华山松20.1 cm、日本落叶松17.8 cm。参照李苏等(2007)的方法记录样树胸径和树种名,然后在树干1.3 m高处的南北方向分别设置网格大小为1 cm ×1 cm、总面积为400 cm2的样方(对于胸径大于9 cm的树种选用20 cm × 20 cm的样方,对于胸径小于9 cm的树种选用10 cm × 40 cm的样方)各1个,逐一记录样方中地衣的名称和盖度。参考有关文献(吴金陵,1987;吕蕾,2011;Clerc,2011;Ohmura,2012)对地衣进行鉴定;最后通过Index Fungorum网(http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/Names.asp)核对拉丁名。

|

|

1) 树种预期地衣丰富度计算研究表明,调查样方数和物种多样性之间存在非线性关系,调查得到的物种丰富度总是低于其真实值,采用合适的物种积累曲线模型可以对样地所容纳的物种丰富度进行无偏估计(Colwell et al., 2012),能更真实地反映调查对象的物种丰富度。参照Colwell等(2012)方法,采用EstimateS 9.1.0软件包预测各树种的预期地衣丰富度,并用Origin 8.1软件绘图。

2) 树干附生地衣群落的物种及生长型组成分析(1) 合并树种内所有调查样方的数据,统计各种地衣的树干附生地衣相对盖度(C)和相对频度(F),计算各地衣种的重要值(N):N=F+C(Hauck et al., 2001;李苏等,2007);(2) 参照罗民波等(2007)方法确定各树种树干附生地衣的优势度(Y):Y=Fi×Pi(Fi为第i物种在某一树种上的出现频率;Pi为第i物种在某一树种上总个体数量的比例),当Y≥0.02时确定为优势种;(3) 参照吴金陵(1987)方法统计各树种鳞叶状、枝状、壳状地衣的种数。

3) 树干附生地衣群落多样性特征分析 (1) 对各树种地衣丰富度在树种间的差异进行单因素ANOVA分析;(2) 各树种地衣群落多样性分析:统计并计算各树种地衣群落的物种丰富度、Shannon-Wiener指数(H)、Simpson指数(D)和均匀度指数(E),其中,H=-∑PilnPi,D=1-∑Pi2,E=H/Hmax,(式中的Pi=Ni/N,Ni为种i的绝对重要值,N为各地衣种重要值之和,而Hmax=lnS,S为群落中的总物种数);计算各树种单株容纳的地衣种数占树种容纳的总地衣种数的比例,作为树种地衣群落的β多样性,其值越大,则单株间的群落结构差异越小;(3) 将7种原生树种和3种引进树种的样方调查数据分别合并,然后计算原生树种组和引进树种组的树干附生地衣群落多样性参数。

4) 树种间地衣群落结构相似性分析以51种地衣在10个树种树干附生地衣群落中的重要值为指标,采用SPSS 19.0软件对10个树种树干附生地衣群落进行系统聚类。

3 结果与分析 3.1 各树种树干附生地衣的预期丰富度差异由图 1可知,各树种的预期地衣丰富度存在差异,表现为华山松(64)>锐齿槲栎(62)>马尾松(57)>灯台树(54)>细花樱桃(51)>巴山冷杉(46)>日本落叶松(45)>川鄂柳(33)>青檀(32)>皂柳(26);同时,引进树种组的预期地衣丰富度均值(55) 高于原生树种组(47)。

|

图 1 10个树种树干附生地衣的物种丰富度积累曲线 Fig.1 Species richness accumulation curve of 10 tree species |

本研究在神农架次生林中共采集51种地衣,涵盖12科26属(表 2)。各树种的地衣物种丰富度存在差异,原生树种的地衣丰富度表现为灯台树(22)>川鄂柳(20)>皂柳(18)>细花樱桃(17)=锐齿槲栎(17)>巴山冷杉(16)>青檀(14),而引进树种中华山松(23)>马尾松(14)=日本落叶松(14)。但是原生树种组的每树种平均地衣丰富度(17.7) 与引进树种组(17.0) 十分接近(表 3)。

|

|

|

|

10个树种树干附生地衣群落的优势种差异较大(表 4), 川鄂柳附生的优势种为大哑铃孢,皂柳为石梅衣和小刺褐松萝,锐齿槲栎为毛边黑蜈蚣衣,细花樱桃和灯台树为毛边黑蜈蚣衣和流苏茶渍,青檀为流苏茶渍、日本珊瑚枝和亚长芽黑尔衣,巴山冷杉为流苏茶渍;在3种引进树种中,华山松为毛边黑蜈蚣衣,马尾松为毛边黑蜈蚣衣、橄榄斑叶梅和黄髓梅,日本落叶松为石梅衣和裂树花。

|

|

10个树种的地衣群落多样性存在一定差异(表 3)。首先,每个树种所支持的地衣种数存在差异,原生树种组中以皂柳最高(每株7.4种)、青檀最低(每株1.6种),引进树种中以华山松最高(每株4.6种)、马尾松最低(每株2.6种);但是,在原生树种组与引进树种组树均地衣种数均为3.7种,二者之间并无差异。同时,各树种内地衣群落的β多样性较高,说明树种内各单株的地衣组成也存在较大差异。

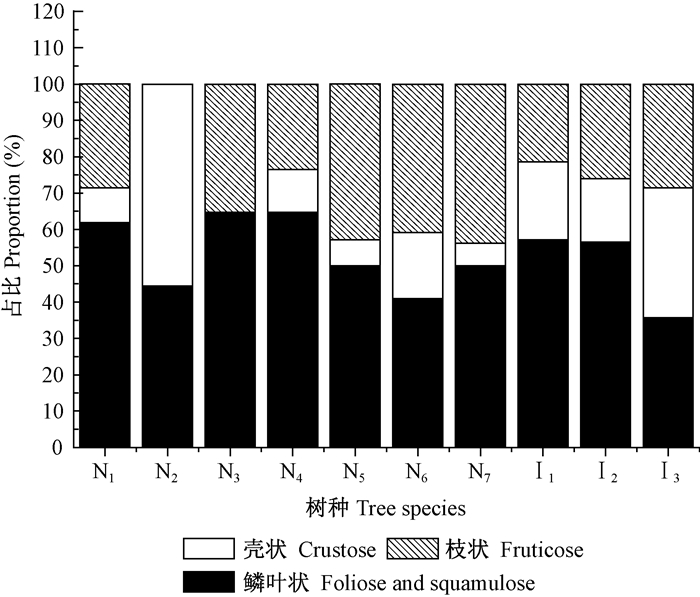

3.4 各树种树干附生地衣生长型的组成差异不同生长型地衣在树种间的分布存在较大差异(表 5、图 2)。其中,皂柳以枝状为主、鳞叶状地衣为辅,无壳状地衣分布;川鄂柳、锐齿槲栎、细花樱桃、青檀、巴山冷杉、马尾松和华山松以鳞叶状地衣为主(50%以上);灯台树的鳞叶状和壳状地衣分布接近(均低于50%),枝状较少;日本落叶松以鳞叶状和枝状地衣为主(35.4%),壳状次之。从种组水平来看,原生树种组共有鳞叶状地衣25种、枝状地衣15种和壳状地衣11种,分别高于引进树种组的16种、9种和7种(表 5)。每个原生树种平均定居的鳞叶状地衣种类(9.86) 和壳状地衣种类(4.86) 也分别高于引进种组的8种和4.67种,但枝状地衣(3.14种)较引进种组(4.00种)略低。

|

|

|

图 2 不同生长型地衣在10个树种上的分布比例 Fig.2 Proportion of lichen growth form inhabited on 10 tree species |

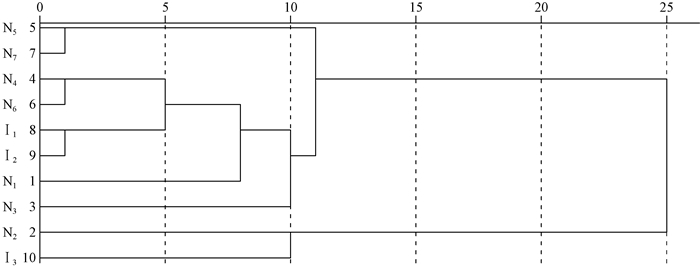

对10个树种树干附生地衣群落的聚类结果见图 3。在步长为10时,可以将10个树种划分为3大类,可反映各树种地衣群落的优势种组成差异。其中,青檀和巴山冷杉聚为一类,附生以流苏茶渍为优势种的地衣群落;细花樱桃、灯台树、马尾松、华山松、川鄂柳和锐齿槲栎聚为一类,除了川鄂柳附生以大哑铃孢为优势种的地衣群落以外,其他均附生以毛边黑蜈蚣衣为优势种或共优种的群落;皂柳和日本落叶松聚为一类,附生以石梅衣为优势种的群落。值得注意的是,皂柳与其他6个原生树种的相似性均较低。

|

图 3 神农架引进树种和原生树种树干附生地衣群落的聚类分析 Fig.3 Cluster analysis of the epiphytic lichen communities on 10 tree species of secondary forests in Shennongjia Mountain |

本研究共采集51种树干附生地衣,分属12科26属,与我国云南哀牢山地区(李苏等,2007)和天山地区(艾尼瓦尔等,2005)相当。本研究仅涉及10个树种树干1.3 m处的局部范围,该地区实际的树生地衣多样性可能比本研究得到的更高。从附生地衣在各树种上的分布水平来看,神农架地区次生林原生树种和引进树种的地衣物种丰富度为14~23种,虽然低于瑞典南部的灰树(Fraxinus excelsior)(Johansson et al., 2007)、意大利的橡树(Quercus pubescens)(Loppi et al., 1996)、北美地区的红杉(Sequoia sempervirens)(Williams et al., 2007)和云杉(Picea sitchensis)(Ellyson et al., 2003),可能是由于本研究选择的样树树龄较小且仅调查了树干部分的原因(Johansson et al., 2007;Li et al., 2015),但是与德国的挪威云杉(Picea abies)(Hauck et al., 2001)、瑞典欧洲山杨(Populus tremula)(Gustafsson et al., 1995)及我国云南哀牢山湿性常绿阔叶林9个建群种(李苏等,2007)的地衣丰富度相当;同时,本研究中各树种的Shannon-Wiener指数(H)和均匀度指数(E)与云南哀牢山地区的地衣多样性相当(李苏等,2007),高于天山整个森林系统的地衣群落(艾尼瓦尔等,2005)。因此,神农架地区次生林整体上拥有较高的树干附生地衣多样性。

树种多样性对于维持神农架地区次生林树干附生地衣多样性具有重要意义。各树种地衣群落的优势种存在明显差异,且部分地衣对宿主树种存在栖息偏好,这与李苏等(2015)和Ódor等(2014)的研究结果一致。研究表明,宿主茎流的NH4+浓度和pH(Dobben et al., 1998)、NO3-和锰离子浓度(Hauck et al., 2005)、穿透雨的有机碳含量(Campbell et al., 2013)、树洞(Fritz et al., 2010)、树皮的光滑度和保水能力(Mal et al., 2005)等都是影响树干地衣多样性的重要因素。本研究中的7个阔叶树种和3个针叶树种,其茎流化学特征及树皮的稳定性可能存在极大差异,因为壳斗科(Fagaceae)植物易于真菌腐生,皮部不容易脱落,而马尾松、巴山冷杉茎流含有松脂、抑菌性物质(樊金拴等,1998),同时较容易脱落等。有关各树种上述特征还缺乏深入研究,各树种特征对其地衣多样性的影响尚无法得出确定结论。

神农架地区次生林的树种组成变化对于该地区地衣多样性水平的潜在影响值得关注。一方面,若马尾松、华山松和日本落叶松大面积种植,部分对原生树种存在选择偏好的地衣,如多孢茶渍、洛氏茶渍、拟橄榄斑叶梅等种类可能消失,这样就会降低该地区的地衣多样性。Rios等(2015)和Nilsen等(2010)均证实,大面积引进单一树种会降低地区的地衣多样性。另一方面,本研究在日本落叶松、华山松和马尾松上收集到了原生树种上没有的美国树花、裂树花、黄果梅衣和大白蜈蚣衣,则可能增加了该地区树干附生地衣物种多样性,因此,引进树种对神农架地区地衣多样性的影响可能与引进栽培的规模有关。在全国实施天然林保护工程的大背景下,神农架地区的华山松、日本落叶松人工林已进入成熟乃至衰退期,这一变化对该地区地衣多样性的潜在影响值得进一步关注。需要特别指出的是,皂柳树种附生地衣种较多,单株支持的地衣多样性也较高,加之其附生的部分地衣是川金丝猴种群的越冬主食,因此具有特殊的保护价值。

5 结论神农架地区次生林拥有较高的树干附生地衣多样性,同时各树种的树干附生地衣物种丰富度、物种组成及多样性指数虽然存在差异,但物种组成的差异尤其突出,说明该地区森林生态系统的树种多样性对于地衣多样性维持具有重要意义。因此,华山松等用材树种的引进、次生林的演替对神农架地区附生地衣多样性的潜在影响值得关注。由于华山松和日本落叶松附生有原生树种并不支持的地衣种,小范围引进可能对该地区地衣多样性有利,而引进马尾松则可能降低该地区地衣多样性。在原生树种中,皂柳树种的附生地衣群落与其他原生树种的相异性均较大,具有特殊的保护价值。

| [] |

樊金拴, 李晓明, 曹玉美, 等. 1998. 巴山冷杉精油抑菌作用研究. 西北林学院学报, 13(3): 50–55.

( Fan J S, Li X M, Cao Y M, et al. 1998. On the inhibiting-germ action of essential oil from Farges Fir. Journal of Northwest Forestry College, 13(3): 50–55. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

葛继稳, 吴金清, 朱兆泉, 等. 1997. 神农架生物圈保护区植物多样性及其保护现状的研究. 植物科学学报, 15(4): 341–352.

( Ge J W, Wu J Q, Zhu Z Q, et al. 1997. Studies on plant diversity and present situation of conservation in Shennongjia Biosphere Reserve, Hubei, China. Plant Science Journal, 15(4): 341–352. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

李广良, 薛亚东, 张于光, 等. 2012. 神农架川金丝猴栖息地森林类型与植物多样性研究. 林业科学研究, 25(3): 308–316.

( Li G L, Xue Y D, Zhang Y G, et al. 2012. Study on habitat forest type and plant diversity of Sichuan snub-nosed monkey in Shennongjia National Nature Reserve. Forest Research, 25(3): 308–316. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

李苏, 刘文耀, 王立松, 等. 2007. 云南哀牢山原生林及次生林群落附生地衣物种多样性与分布. 生物多样性, 15(5): 445–455.

( Li S, Liu W Y, Wang L S, et al. 2007. Species diversity and distribution of epiphytic lichens in the primary and secondary forests in Ailao Mountain, Yunnan. Biodiversity Science, 15(5): 445–455. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

刘文耀, 马文章, 杨礼攀. 2006. 林冠附生植物生态学研究进展. 植物生态学报, 30(3): 163–174.

( Liu W Y, Ma W Z, Yang L P. 2006. Advances in ecological studies on epiphytes in forest canopies. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology, 30(3): 163–174. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

罗民波, 陆健健, 王云龙, 等. 2007. 东海浮游植物数量分布与优势种. 生态学报, 27(12): 5076–5085.

( Luo M B, Lu J J, Wang Y L, et al. 2007. Horizontal distribution and dominant species of phytoplankton in the East China Sea. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 27(12): 5076–5085. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-0933.2007.12.016 [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

吕蕾. 2011. 中国西部茶渍属地衣的研究. 济南: 山东师范大学博士学位论文. ( Lü L. 2011. Study on the lichen genus Lecahora from Western China. Ji'nan:PhD thesie of Shandong Normal University. [in Chinese.]) http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10445-1011082246.htm |

| [] |

铁军, 张晶, 彭林鹏, 等. 2010. 神农架川金丝猴冬春季节食性分析. 生态学杂志, 29(1): 64–70.

( Tie J, Zhang J, Peng L P, et al. 2010. Feeding habits of Rhinopithecus roxellana in Shennongjia Nature Reserve of China in winter and spring. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 29(1): 64–70. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

艾尼瓦尔·吐米尔, 阿地里江·阿不都拉, 阿不都拉·阿巴斯. 2005. 天山森林生态系统附生地衣植物群落数量分类及其物种多样性的研究. 植物生态学报, 29(4): 615-622. ( Tumur A, Abdulla A, Abbas A. 2005. Numerical classification and species diversity of corticolous lichen communities in forest ecosystems of the Tianshan Mountains. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology, 29(4):615-622. [in Chinese]) http://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?filename=zwsb20050400c&dbname=CJFD&dbcode=CJFQ |

| [] |

吴金陵. 1997. 中国地衣植物图鉴. 北京, 展望出版社.

( Wu J L. 1997. Lichen lconography of China. Beijing, China Outlook Press. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

张于光, 宿秀江, 丛静, 等. 2014. 神农架土壤微生物群落的海拔梯度变化. 林业科学, 50(9): 161–166.

( Zhang Y G, Su X J, Cong J, et al. 2014. Variation of soil microbial community along elevation in the Shennongjia Mountain. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 50(9): 161–166. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] | Boudreault C, Coxson D S, Vincent E, et al. 2008. Variation in epiphytic lichen and bryophyte composition and diversity along a gradient of productivity in Populus tremuloides stands of northeastern British Columbia, Canada. Ecoscience, 15(1): 101–112. DOI:10.2980/1195-6860(2008)15[101:VIELAB]2.0.CO;2 |

| [] | Campbell J, Bengtson P, Fredeen A L, et al. 2013. Does exogenous carbon extend the realized niche of canopy lichens? Evidence from sub-boreal forests in British Columbia. Ecology, 94(5): 1186–1195. DOI:10.1890/12-1857.1 |

| [] | Clerc P. 2011. Notes on the genus Usnea Adanson (lichenized Ascomycota). Bibliotheca Lichenologica, 106(1): 41–51. |

| [] | Colwell R, Chao A, Gotelli NJ, et al. 2012. Models and estimators linking individual-based and sample-based rarefaction, extrapolation and comparison of assemblages. Journal of Plant Ecology, 20(1): 3–21. |

| [] | Dobben H F V, Braak C J F T. 1998. Effects of atmospheric NH3 on epiphytic lichens in the Netherlands: the pitfalls of biological monitoring. Atmospheric Environment, 32(3): 551–557. DOI:10.1016/S1352-2310(96)00350-0 |

| [] | Ellis C J, Coppinsa B J, Dawsonb T P. 2007. Predicted response of the lichen epiphyte Lecanora populicola to climate change scenarios in a clean-air region of Northern Britain. Biological Conservation, 135(3): 396–404. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.10.036 |

| [] | Ellyson W J T, Sillett S C. 2003. Epiphytecommunities on Sitka spruce in an old-growth redwood forest. Bryologist, 106(2): 197–211. DOI:10.1639/0007-2745(2003)106[0197:ECOSSI]2.0.CO;2 |

| [] | Fritz Ö, Clausen J H. 2010. Rot holes create key microhabitats for epiphytic lichens and bryophytes. Biological Conservation, 143(4): 1008–1016. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.01.016 |

| [] | Gustafsson L, Eriksson I. 1995. Factors of importance for the epiphytic vegetation of aspen Populus tremula with special emphasis on bark chemistry and soil chemistry. Journal of Applied Ecology, 32(2): 412–424. DOI:10.2307/2405107 |

| [] | Haig A R, Matthes U, Larson D W. 2000. Effects of natural habitat fragmentation on the species richness, diversity, and composition of cliff vegetation. Canadian Journal of Botany, 78(6): 786–797. DOI:10.1139/b00-047 |

| [] | Halonen P, Hyvärinen M, Kaupp M. 1991. The epiphytic lichen flora on conifers in relation to climate in the Finnish middle boreal subzone. The Lichenologist, 23(1): 61–72. DOI:10.1017/S0024282991000117 |

| [] | Hauck M, Junge R, Runge M. 2001. Relevance of element content of bark for the distribution of epiphytic lichens in a montane spruce forest affected by forest dieback. Environmental Pollution, 112(2): 221–227. DOI:10.1016/S0269-7491(00)00112-3 |

| [] | Hauck M, Spribille T. 2005. The significance of precipitation and substrate chemistry for epiphytic lichen diversity inspruce-fir forests of the Salish Mountains, northwestern Montana. Flora, 200(6): 547–562. DOI:10.1016/j.flora.2005.06.006 |

| [] | Hawksworth D L, Rost F. 1970. Qualitative scale for estimating sulphur dioxide air pollution in England and Wales using epiphytic lichens. Nature, 227(11): 146–148. |

| [] | Holt E A, McCune B, Neitlich P. 2008. Grazing and fire impacts on macrolichen communities ofthe Seward Peninsula, Alaska, U. S.A. The Bryologist, 111(1): 68–83. DOI:10.1639/0007-2745(2008)111[68:GAFIOM]2.0.CO;2 |

| [] | Johansson P, Rydin H G. 2007. Tree age relationships with epiphytic lichen diversity and lichen life history traits on ash in southern Sweden. Ecoscience, 14(1): 81–91. DOI:10.2980/1195-6860(2007)14[81:TARWEL]2.0.CO;2 |

| [] | Király I, Nascimbene J, Tinya F, et al. 2013. Factors influencing epiphytic bryophyte and lichen species richness at different spatial scales in managed temperate forests. Biodiversity and Conservation, 22(1): 209–223. DOI:10.1007/s10531-012-0415-y |

| [] | Lange O L, Belnap J, Reichenberger H. 1998. Photosynthesis of the cyanobacterialsoil-crust lichen Collema tenax from arid lands in southern Utah, USA: role of water content on light and temperature responses of CO2 exchange. Functional Ecology, 12(2): 195–202. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2435.1998.00192.x |

| [] | Leppik E, Jüriado I. 2008. Factors important for epiphytic lichen communities in wooded meadows of Estonia. Folia Cryptogamica Estonica, 44(1): 75–87. |

| [] | Li S, Liu W Y, Li D W. 2013. Epiphytic lichens in subtropical forest ecosystems in southwest China. Biological Conservation, 159(1): 88–95. |

| [] | Li S, Liu W Y, Li D W, et al. 2015. Species richness and vertical stratification of epiphytic lichens in subtropical primary and secondary forests in southwest China. Fungal ecology, 17(1): 30–40. |

| [] | Loppi S, Dominicis V D. 1996. Effects of agriculture on epiphytic lichen vegetation in central Italy. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences, 44(4): 297–307. DOI:10.1080/07929978.1996.10676653 |

| [] | Mal T D, Roberts G E. 2005. Host associations of the strangler fig Ficus watkinsiana in a subtropical Queensland rain forest. Austral Ecology, 30: 229–236. DOI:10.1111/aec.2005.30.issue-2 |

| [] | Nilsen K W, Bjerke J W, Beck P S A, et al. 2010. Epiphytic macrolichens in spruce plantations and native birch forests along a coast-inland gradient in North Norway. Boreal Environment Research, 15(1): 43–57. |

| [] | Ódor P, Király I, Tinya F, et al. 2014. Patterns and drivers of species composition of epiphytic bryophytes and lichens in managed temperate forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 321: 42–51. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2014.01.035 |

| [] | Ohmura Y. 2012. A synopsis of the lichen genus Usnea (Parmeliaceae, Ascomycota) in Taiwan. Memories of the National Science Museum, Tokyo, 48: 91–137. |

| [] | Rios A I A, Moncada B, Lücking R. 2015. Epiphyte homogenization andde-diversification on alien Eucalyptus versus native Quercus forest in the Colombian Andes: a case study using lirellate Graphidaceae lichens. Biodiversity & Conservation, 24(5): 1239–1252. |

| [] | Rogers P C, Ryel R J. 2008. Lichen community change in response to succession in aspen forests of the southern Rocky Mountains. Forest Ecology and Management, 256(10): 1760–1770. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2008.05.043 |

| [] | Schmull M, Spribille T. 2002. Site factors determining epiphytic lichen distribution in adieback-affected spruce-fir forest on Whiteface Mountain, New York: Stemflow Chemistry. |

| [] | Thor G, Johansson P, Jönsson M T. 2010. Lichen diversity andred-listed lichen species relationships with tree species and diameter in wooded meadows. Biodiversity & Conservation, 19(8): 2307–2328. |

| [] | Williams C B, Sillett S C. 2007. Epiphyte communities on redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) in northwestern California. Bryologist, 110(3): 420–452. DOI:10.1639/0007-2745(2007)110[420:ECORSS]2.0.CO;2 |

| [] | Wolseley P A, Hudson B A. 1997. The ecology and distribution of lichens in tropical deciduous and evergreen forests of northern Thailand. Journal of Biogeography, 24(3): 327–343. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2699.1997.00124.x |

2017, Vol. 53

2017, Vol. 53