文章信息

- 字洪标, 向泽宇, 王根绪, 阿的鲁骥, 王长庭

- Zi Hongbiao, Xiang Zeyu, Wang Genxu, Ade Luji, Wang Changting

- 青海不同林分土壤微生物群落结构 (PLFA)

- Profile of Soil Microbial Community under Different Stand Types in Qinghai Province

- 林业科学, 2017, 53(3): 21-32.

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2017, 53(3): 21-32.

- DOI: 10.11707/j.1001-7488.20170303

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2015-10-03

- 修回日期:2017-01-19

-

作者相关文章

2. 中国科学院水利部成都山地灾害与环境研究所 成都 610041

2. Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, CAS Chengdu 610041

土壤微生物是森林生态系统的重要组成部分,其参与土壤有机质的分解、矿质营养的吸收释放、物质循环和成土过程,并将有机物转化为植物可利用养分,被认为是土壤养分转化和循环以及有机碳代谢的主要驱动力 (Baldock et al., 2000;Rutigliano et al., 2004;牛小云等,2015;翟辉等,2016)。土壤微生物对外界条件如植被、土壤、气候等的变化十分敏感,即使在相同立地条件下,不同林分组成的群落中土壤微生物量也具有较大差异,同一种植物土壤微生物群落组成随植物年龄以及发育阶段而改变 (Shillam et al., 2008;Adair et al., 2013;Yang et al., 2014; 牛小云等,2015)。因此,研究森林生态系统中土壤微生物群落的变化规律对于认识生态系统过程和功能具有重要意义 (Zhong et al., 2010)。

植物与微生物之间是相互联系的,作为生产者的植物为土壤微生物提供碳源,而土壤微生物参与分解90%以上的枯落物以及动物残体,将有机物转化为植物可利用养分,直接为植物生长提供必需的物质养分 (Wall et al., 1999;易秀等,2011)。植被物种间的差异为土壤环境和生物群落的特异性创造条件 (De Deyn et al., 2008),因为植物物种的变化可以改变植物残体的有机组成和产量,从而改变异养微生物群落的组成和功能 (Zak et al., 2003;Hobbie et al., 2007)。植物凋落物是联系地上和地下的桥梁,其化学组分的多样性与土壤微生物多样性存在正相关关系 (Meier et al., 2008)。而在森林生态系统中优势种植物凋落物的可利用性和组成在很大程度上影响了土壤有机质 (Aneja et al., 2006),而土壤中异养微生物群落的结构和功能主要和土壤有机质的质量有关 (Tscherko et al., 2005;Merila et al., 2010)。然而,大部分土壤微生物不易培养,研究其群落组成十分困难。但随着微生物研究手段深入,发现磷脂脂肪酸 (PLFAs) 分析方法能较完整地检测到样品中微生物群落变化,且受微生物生理影响不大 (Saetre et al., 2000),同时提供了土壤微生物生物量 (Joergensen et al., 2006) 及其群落结构信息 (Frostegård et al., 1993a),而被广泛用于微生物群落组成的测定 (王淼等,2014;吴则焰等,2014;杨君珑等,2015)。

青海地处青藏高原,森林多分布在2 000~4 000 m的高海拔地区,以寒温带针叶林为主,生态地位极其重要。青海省森林资源地带性分布明显,但不均匀,森林类型多但生产力低 (卢航等,2013)。目前,对青海森林生态系统结构和功能的研究相对较少,特别是土壤微生物群落组成、多样性对森林类型变化的响应方面。本研究以青海云杉 (Picea crassifolia)、白桦 (Betula platyphylla)、落叶松 (Larix gmelinii) 和山杨 (Populus davidiana) 组成的7种林型,即大通青海云杉天然林、大通白桦次生林、湟中白桦青海云杉天然混交林、乐都落叶松白桦天然混交林、民和山杨人工林、循化山杨白桦次生混交林和尖扎青海云杉天然林,为研究对象,采用PLFAs方法研究不同森林类型土壤微生物生物量和微生物群落结构组成的变化,旨在探讨林型对土壤微生物生物量和组成的影响,了解不同林型土壤微生物群落组成变化规律,为该区森林土壤资源的科学管理与评价以及林分结构调整和森林生态系统的更新、恢复与重建提供参考。

1 研究区概况青海省位于青藏高原东北部 (89°35′—103°4′ E,31°39′—39°19′ N),东西长约1 200 km,南北宽约800 km,青海省土地总面积7 215.24万hm2。其中林地面积634.00万hm2,占8.79%;森林面积329.56万hm2,占林地面积51.98%,森林覆盖率4.57%。燕山运动奠定地形复杂多样,高山、丘陵、河谷、盆地交错分布,平均海拔3 000 m以上,属典型高原大陆性气候。年均气温-3.7~6.0 ℃,年日照2 340~3 550 h,年降水量16.7~776.1 mm (大部分400 mm以下),年蒸发量1 118.4~3 536.2 mm (董旭,2009)。

2 研究方法 2.1 试验设计、凋落物收集、土样和细根采集在青海省大通县、湟中县、乐都县、民和县、循化县和尖扎县分别选取大通青海云杉天然林 (A)、大通白桦次生林 (B)、湟中白桦青海云杉天然混交林 (C)、乐都落叶松白桦天然混交林 (D)、民和山杨人工林 (E)、循化山杨白桦次生混交林 (F) 和尖扎青海云杉天然林 (G)7种林分类型,各林分类型概况见表 1,林龄、平均胸径和平均树高见表 2。在每种林型下,随机设置3块间距大于100 m的50 m × 20 m样地。于2011年7—8月在每块样地内收集3个1 m × 1 m样方的凋落物,用来测定凋落物现存量。在每块样地内用土钻法 (直径5 cm) 随机采集表层土壤 (0~20 cm) 样品各9个,每块样地的9个土样充分混合均匀,装入无菌袋中用冰盒带回实验室,并过2 mm筛后挑取土壤中的残留根系、石块及其他杂质后,将土壤分成2部分:一部分土样风干后用于土壤理化性质的测定;另一部分土样保存于-80 ℃超低温冰箱内,用于磷脂脂肪酸 (phospholipid fatty acids,PLFAs) 测定。细根生物量采用土钻法,在每块样地随机取30个土钻,每10个土钻混合为1个样品,清水冲洗得到根系样品。

|

|

|

|

土壤有机碳含量测定采用重铬酸钾加热法;土壤含水量测定采用烘干法;pH值测定采用电位法 (水:土=2.5:1);土壤密度测定采用环刀法;细根生物量采用土钻法;凋落物现存量采用收获法;细根生物量和凋落物现存量测定方法为在65 ℃烘干称恒质量 (中国科学院南京土壤研究所,1983;王长庭等,2010;李立平等,2004)。

2.3 磷脂脂肪酸的测定PLFA的测定方法采用改进的Bligh-Dyer方法 (Bligh et al.,1959),以酯化C19: 0为内标,用Agilent 7890A/5975C气相色谱质谱联用仪对提取出来的脂肪酸进行分析。磷脂脂肪酸 (PLFA) 的命名采用Frostegård方法命名 (Frostegård et al.,1993a)。根据已有的研究结果,指示特定微生物的PLFA标记物如表 3。土壤微生物含量的标定与计算参照刘波等 (2010)所介绍的方法。

|

|

用所测得的PLFA数据计算多样性指数 (孙海新等,2004),Shannon-Wiener指数 (H) 计算公式为:

| $H = - \sum\limits_{i = 1}^S {{P_i}} {\rm{ln}}{P_i};$ |

式中:Pi=Ni/N,Ni为第i种磷脂脂肪酸含量,N为该实验中所有磷脂脂肪酸含量总和;S为同一样品中检测出的脂肪酸甲酯的种数。

Simpson指数 (D) 计算公式为:

| $D = 1 - \sum {({N_i}/N)^2};$ |

Margalef物种丰富度指数 (M) 计算公式为:

| $M = \left( {S - 1} \right)/{\rm{ln}}N。$ |

试验数据均在SPSS 16.0和Canoco for windows 4.5软件中进行统计分析,统计图形在Origin 8.0中绘制。采用单因素方差 (one-way ANOVA) 分析林分类型对土壤理化性质、微生物生物量和微生物群落多样性的影响;采用Canoco 4.5中的线性冗余分析 (redundancy analysis,RDA) 来解释土壤环境因子与微生物特性间的关系,分析前数据进行lg (X+1) 转换,使用Monte Carlo置换进行显著性检验 (P<0.05);采用Pearson相关分析检测土壤微生物群落特征与微生物多样性指数的关系。

3 结果与分析 3.1 土壤理化性质、细根生物量和凋落物现存量由表 4可知,土壤有机碳含量表现为A>G>C>F>B>D>E,其中A最大为116.4 g·kg-1,E最小仅为37.24 g·kg-1,且表现出天然针叶林>阔叶、阔叶混交次生林>针阔混交天然林>人工林。土壤pH值表现为F和G为碱性,其他类型为酸性。土壤密度表现为D>E>B>A>C>F>G,其中最大D达到1.63 g·kg-1,最小G仅为0.53 g·cm-3。土壤含水量差异显著,表现为B>A>C>G>D>E>F。细根生物量表现出A和C最大,B和D最小。凋落物现存量表现为D>B>C>G>F>A>E,最大D达到879.75 g· m-2,最小E仅为203.23 g· m-2。

|

|

本研究中不同林型土样共检测出17种磷脂脂肪酸 (PLFAs),碳链长度为C13~C18,包含各种饱和脂肪酸、不饱和脂肪酸、甲基化分支脂肪酸和环丙烷脂肪酸生物标记。在A和G中PLFAs的主要类型是代表革兰氏阳性菌的a14:0、代表革兰氏阴性菌的16:1ω9c和代表广义细菌的16:0,这3种类型之和分别占A和G林分PLFAs总量的69.07%和70.40%。在B和C中PLFAs的主要类群是代表革兰氏阳性菌的i14:0、代表革兰氏阴性菌的16:1ω9c和广义细菌的16:0,这3种类型之和分别占B和C林分PLFAs总量的67.93%和69.08%。D中PLFAs的主要类群是代表革兰氏阳性菌的i14:0,代表广义细菌的15:0和16:0,这3种类型之和占PLFAs总量的64.92%。E中的主要类群是代表广义细菌的15:0和16:0,这2种类型之和占PLFAs总量的51.95%。F中PLFAs的主要类群是代表革兰氏阴性菌的16:1ω9c,代表广义细菌的15:0和16:0,这3种类型之和占PLFAs总量的74.84%。在所有检测的土壤样品中,16:0的检测值均为最大,其含量为8.68~30.13 nmol·g-1;碳饱和脂肪酸是土样中含量最丰富的脂肪酸种类的,其相对含量为69.60%~85.89%(表 5)。结果表明,不同林分类型其土壤微生物群落存在差异,但是林分组成相似的群落其土壤微生物优势类群也基本相同。此外,16:0是青海森林主要土壤微生物类群,最主要的脂肪酸种类是饱和脂肪酸。

|

|

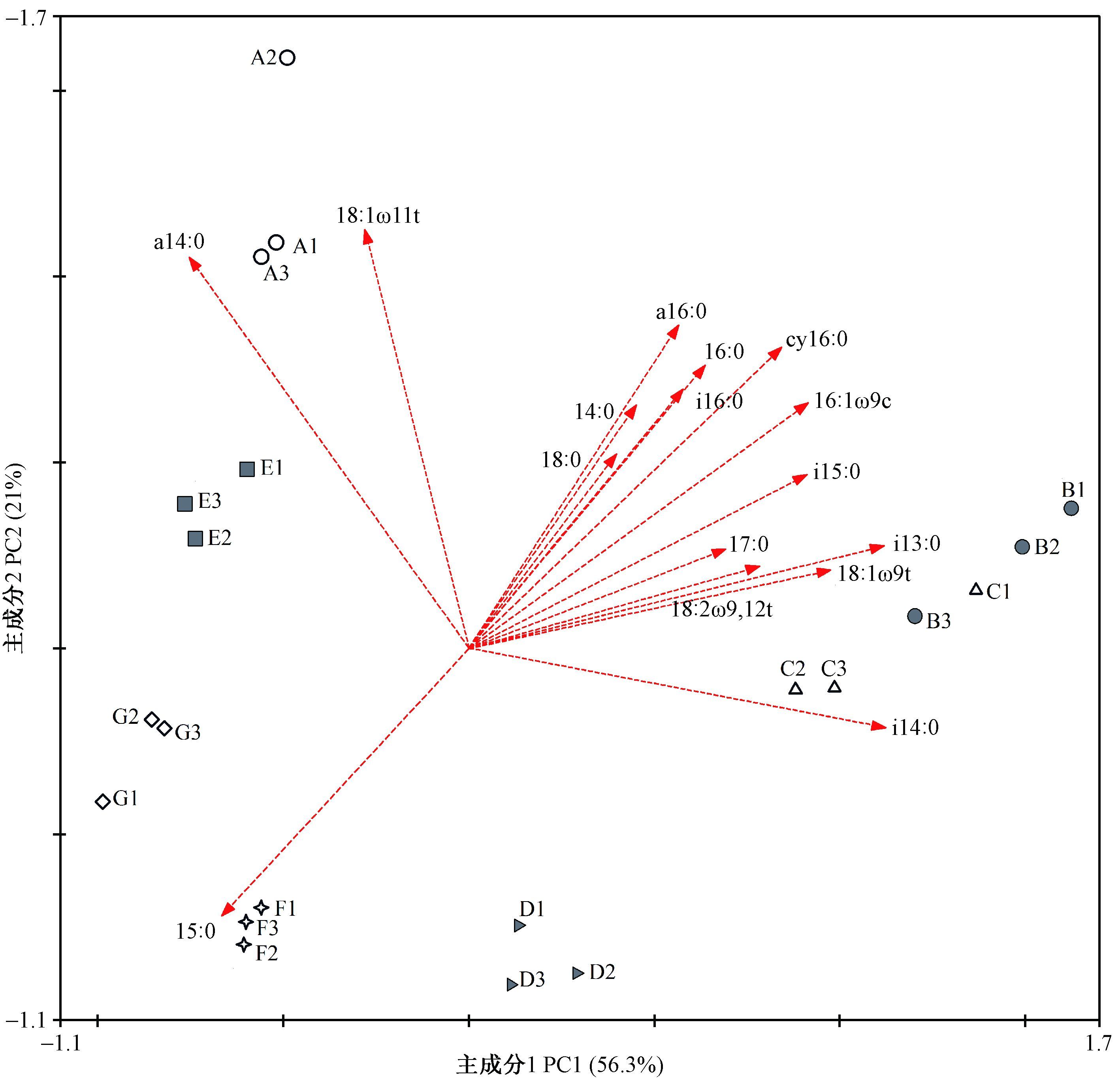

对7种不同林分类型土壤微生物群落PLFAs进行主成分分析,结果表明:第1主成分 (PC1) 的贡献率为56.3%,主成分2(PC2) 的贡献率为21.0%,累积贡献率为77.3%(图 1),表明前2个主成分是解释土壤微生物群落变异的主要贡献者。PCA图中代表不同林分类型的土壤微生物群落PLFAs分布于不同区域,表明微生物群落组成在不同林分类型存在差异。其中,B和C平行样本分布区域有所混杂,说明这2个林分类型土壤微生物群落差异较小。其余5个林分类型各自分布在不同区域,说明它们之间微生物差异较大。17种磷脂脂肪酸中与PC1显著相关的有11种,其中代表广义细菌的有15:0,16:0和17:0,代表革兰氏阳性菌的有i13:0,i14:0,i15:0和i16:0,代表革兰氏阴性菌的有16:1ω9c和cy16:0,代表真菌的有18:1ω9t和18:2ω9, 12t;与PC2显著相关的有4种,其中代表广义细菌的有14:0,代表革兰氏阳性菌的有a14:0和a16:0,代表革兰氏阴性菌的有18:1ω11t。主成分分析表明广义细菌和革兰氏阳性菌是土壤微生物群落类群的主要成分。

|

图 1 不同林分类型土壤微生物PLFAs的主成分分析 Fig.1 The principal component analysis of soil microbial community PLFAs in different stand types |

由表 6可知,不同林型土壤微生物各菌群PLFA含量和微生物总量均有差异。B的微生物总量和细菌含量均最高,分别为为112.07和100.67 nmol·g-1,G最低,分别为22.42和21.09 nmol·g-1。不同林型土样的微生物总量表现为B>C,E>A>D>F,G,革兰氏阳性菌含量表现为B>C>A>E,D>G>F,革兰氏阴性菌含量表现为B>C,A>E>F,D,G;真菌含量则表现为B>C>E>D,F,A,G。

|

|

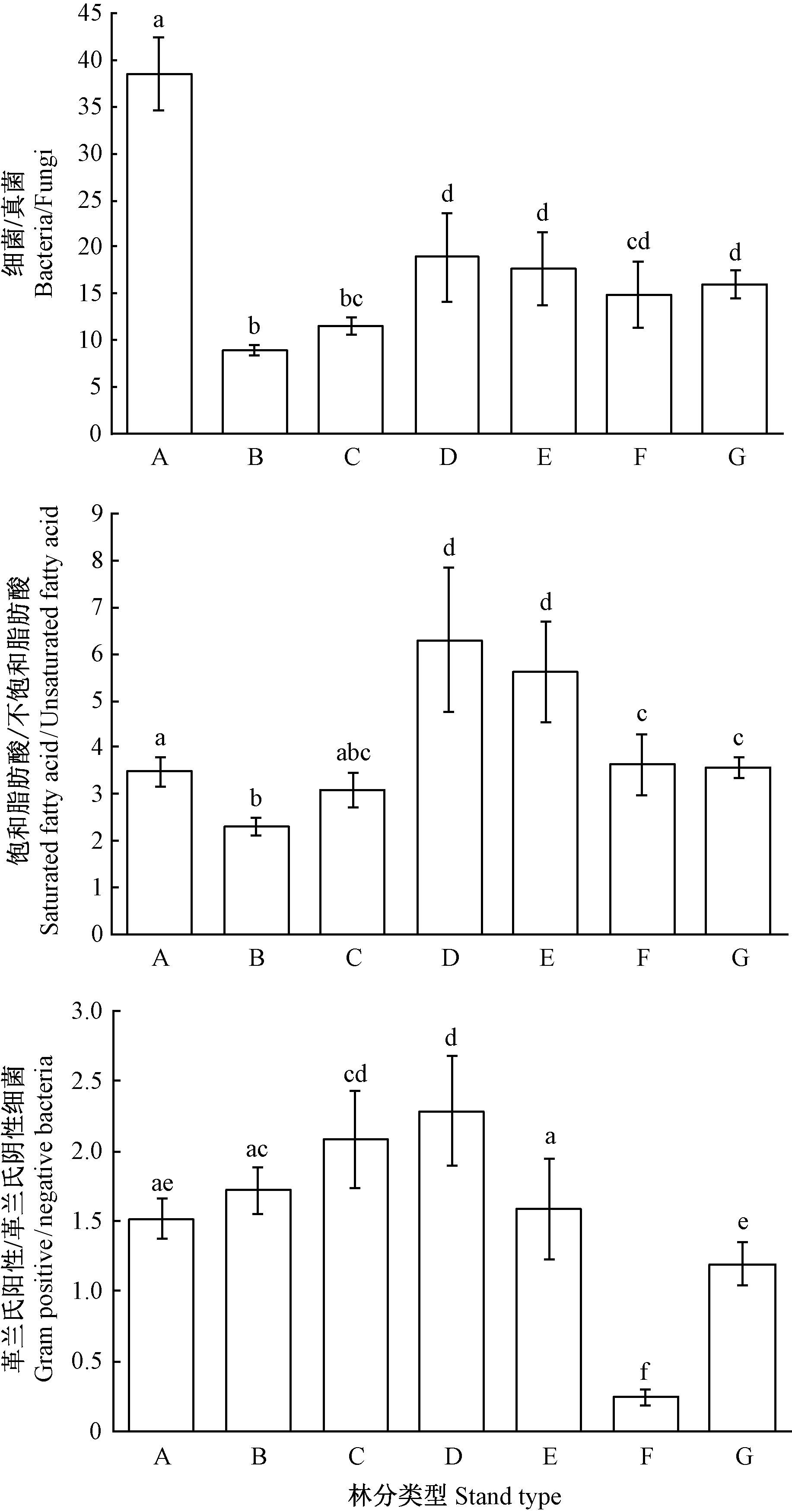

不同林型土壤微生物群落中不同菌群PLFAs比值不同,各菌群的比值可反映微生物不同菌群相对含量和种群相对丰度的变化 (图 2)。其中细菌与真菌的比值表现为A>D>E>G>F>C>B,B的细菌与真菌脂肪酸比值最低,为8.87,A的细菌与真菌脂肪酸比值则最高,为38.51;饱和脂肪酸与不饱和脂肪酸的比值表现为D>E>F>G>A>C>B,其中在D最高,B最低;革兰氏阳性菌与革兰氏阴性菌的比值则表现为D>C>B>E>A>G>F,且F显著小于其他林分类型。

|

图 2 不同林分土壤微生物不同菌群PLFAs比值 Fig.2 Ratios of the different microbial groups PLFAs content in different stand types 相同字母表示差异不显著 (P>0.05),不同字母表示差异显著 (P<0.05)。下同。 The same letters indicate no significant difference (P > 0.05), and different letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).The same below. |

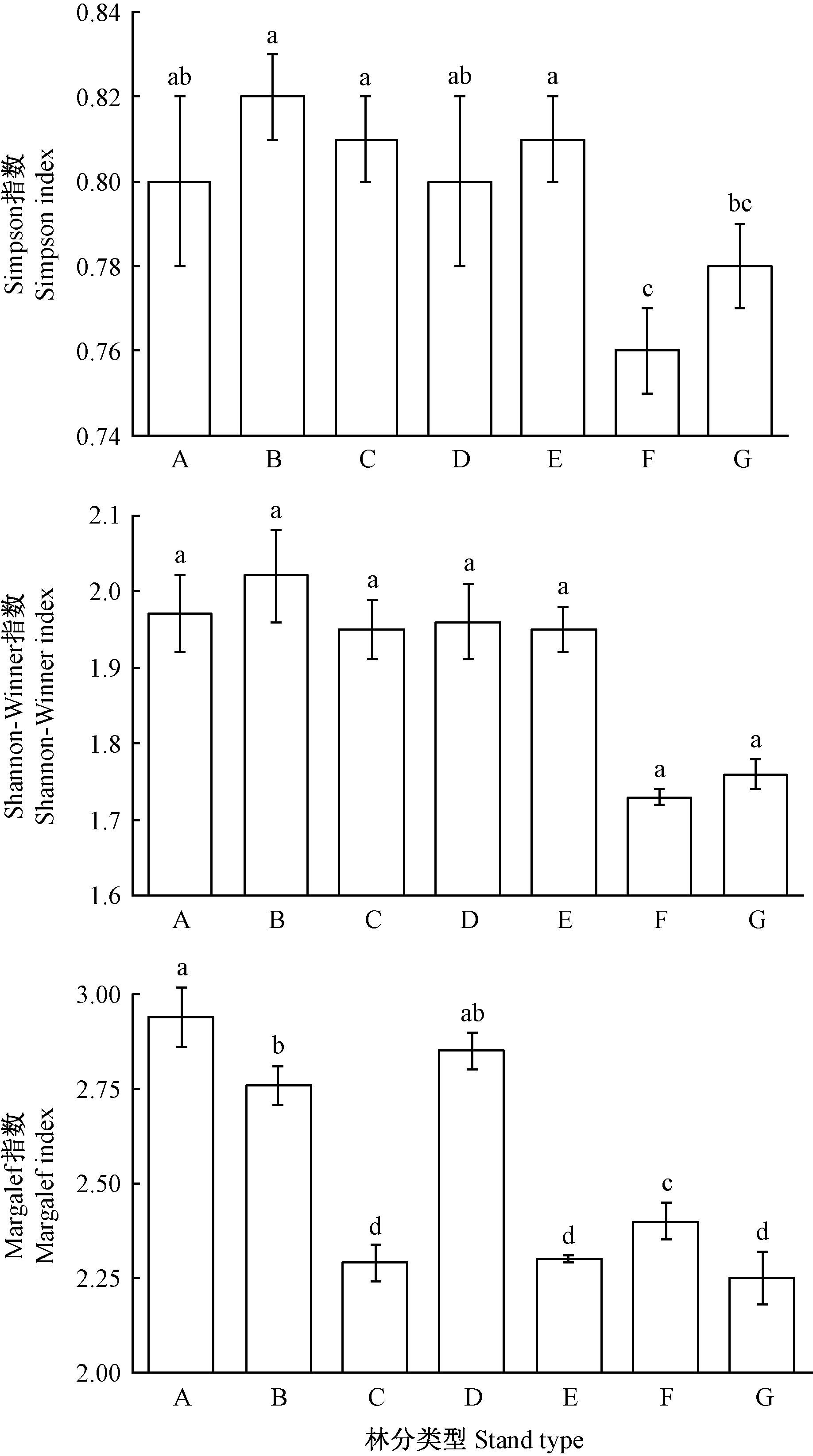

用Simpson多样性指数、Shannon-Wiener多样性指数和Margalef物种丰富度指数综合描述不同林分土壤微生物群落特征,进一步揭示土壤微生物的多样性,结果见图 3。从图 3可以看出多样性在F和G显著小于其他林分 (P<0.05);A和B物种丰富度指数与D均无显著差异 (P>0.05),但C,E,G<F<B<A,且这几组间均差异显著 (P<0.05)。

|

图 3 不同林分土壤微生物群落多样性 Fig.3 Diversity of microbial communities in soils under different forest types |

由表 7可知,Simpson指数和Shannon-Winner多样性指数与磷脂脂肪酸总量、细菌PLFA含量、真菌PLFA含量、革兰氏阳性菌PLFA含量、革兰氏阴性菌PLFA含量以及革兰氏阳性菌PLFA含量与革兰氏阴性菌PLFA含量比值、饱和脂肪酸PLFA含量、不饱和脂肪酸PLFA含量显著正相关,而Margalef物种丰富度指数与细菌PLFA含量/真菌PLFA含量显著正相关。

|

|

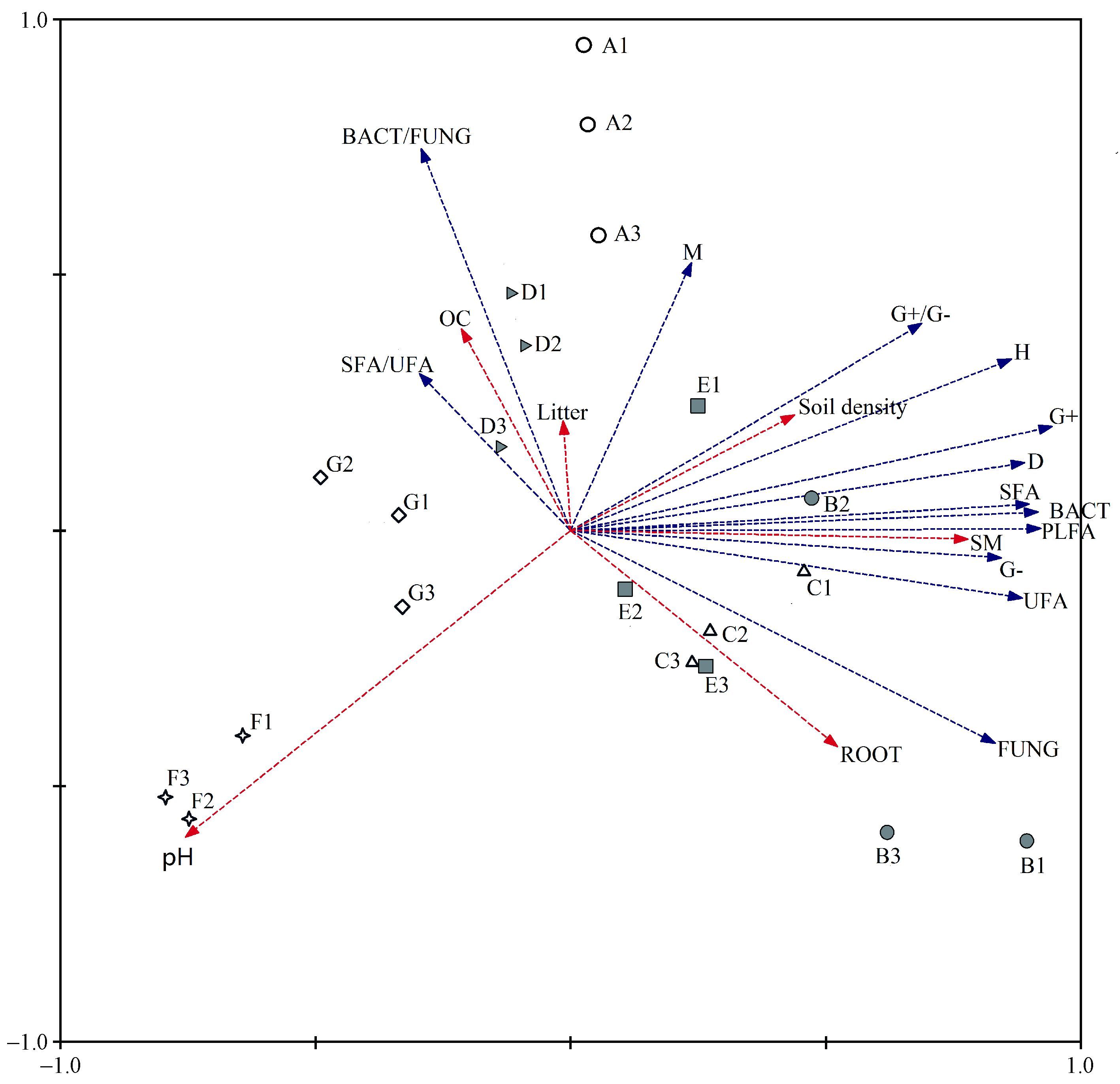

由土壤微生物群落特征与环境变量的RDA分析 (图 4,表 8) 可知,6个环境变量共解释了土壤微生物群落特征变异的87.7%,基于所有典范特征值的Monte Carlo置换检验表明微生物群落特征与环境变量之间显著相关 (P =0.002)。RDA排序结果表明环境因子变量很好地解释了土壤微生物群落特征的变异,RDA前2轴 (74.2%和7.3%) 解释的变异量比后2轴 (4.1%和2.1%) 多,说明前2轴是解释土壤微生物群落特征组成变异的主要贡献者。与RDA第一排序轴显著相关的是pH值 (P<0.001)、含水量 (P<0.001) 和细根生物量 (P<0.05),pH值 (P<0.05) 还与RDA第二轴显著相关,与RDA第三轴显著相关的是有机碳含量 (P<0.001)、密度 (P<0.001)、含水量 (P<0.05) 和凋落物现存量 (P<0.05);说明RDA 1轴主要代表了pH值、含水量和细根生物量,RDA 3轴主要代表了有机碳含量、密度和凋落物现存量。

|

图 4 土壤微生物群落特征与环境变量间的RDA分析 Fig.4 RDA analysis of between the soil microbial properties and the environmental variables OC:土壤有机碳含量Soil organic carbon content; SM:土壤含水量Soil moisture content; Soil density:土壤密度;Root:细根生物量Fine root biomass;Litter:凋落物现存量Litter standing crop;M:Margalef指数Margalef index;D: Simpson指数Simpson index;H:Shannon-Wiener指数Shannon-Wiener index;PLFA:PLFA总量Total content of PLFAs;G+:革兰氏阳性菌含量Content of gram positive bacteria;G-:革兰氏阴性菌含量Content of gram negative bacteria;G+/G-:革兰氏阳性菌与阴性菌含量比值Ratio of content of gram positive bacteria to gram negative bacteria;BACT:细菌含量Content of bacterial;FUNG:真菌含量Content of fungi;BACT/FUNG:细菌含量与真菌含量比值Ratio of content of bacteria to fungi;SFA:饱和脂肪酸含量Content of saturated fatty acid;UFA:不饱和脂肪酸含量Content of unsaturated fatty acid;SFA/UFA:饱和脂肪酸与不饱和脂肪酸含量比值Ratio of content of saturated fatty acid to unsaturated fatty acid. |

|

|

研究土壤中PLFAs总浓度变化、特征脂肪酸的组分差异,可深人了解微生物群落结构的变化。因为PLFAs含量提供了土壤中的微生物量信息 (Frostegård et al., 1991),特征脂肪酸的组分则可表征微生物群落结构 (Frostegård et al., 1993b)。本研究中,由云杉、白桦、落叶松和山杨4种常见树种组成的7种不同林分的土壤微生物群落结构和组分含量存在显著差异。一方面是不同林分类型的土壤有机碳的积累和储存是不同的 (丁访军等,2012;向泽宇等,2014),从而造成养分含量差异,而土壤微生物群落的代谢活性以及组成在很大程度上是由生物地球化学循环、土壤有机物的代谢过程以及土壤的肥力和质量等因素所决定 (胡雷等,2015)。另一方面,土壤微生物的群落特征受到植物物种、植物根系及根系分泌物等因素的影响 (Zak et al., 2003),而本研究正是在不同林分条件下进行研究,林分组成存在差异,进而造成微生物群落结构差异。此外,不同的土壤环境条件和林分特征 (植被属性) 反应不同功能群的土壤微生物,并以特定的方式影响土壤微生物群落的组成。树木还能影响林下植被群落的组成,林下植被群落也可以和土壤微生物相互作用,从而间接影响土壤微生物 (Prescott et al., 2013)。

植物与土壤微生物之间的相互依存关系,植物通过其凋落物、根系分泌物为土壤微生物提供营养,导致植物和微生物之间的协同进化,促进土壤微生物的多样性。例如,阔叶和针叶植被的生化组成、植被物种间的差异,植物多样性的改变能够引起植物生物量、凋落物量及其有机组分的变化,会影响微生物群落组成和功能 (蒋婧等,2010;De Deyn et al., 2008)。本研究也发现,针叶林 (如A和G) 的真菌生物量最低,阔叶林 (如B,C和E) 细菌生物量最高,说明了针叶林和阔叶林间土壤微生物群落组成存在差异。造成原因可能是有些植物凋落物中含有抑制细菌活动的酚、醛等成分,从而间接地影响凋落物的分解率 (Gordon, 1998)。另外,富含低分子酚类化合物的凋落物,进入土壤后控制着真菌占优势的微生物对氮的固持,加剧了低养分的状况 (Wilson et al., 1992);而富含碳水化合物和糖类的凋落物,促进了细菌占优势的食物网,提高了生境的养分状况会促进细菌的生长 (Wardle, 1999;Bardgett et al., 2005)。因此,林型 (针叶林、阔叶林和针阔混交林) 不同,植物组成不同进而引起凋落物及其分解速率的变化,造成回归土壤中养分的质量和数量产生差异,从而影响了微生物群落的组成和多样性。

有研究表明:细根对水分和养分有很强的吸收作用 (Rosenvald et al., 2011),植物本身的化学组成和特征制约着枯落物的分解和矿化过程,从而影响着植物的养分归还 (郭雪莲等,2007)。不同土地利用类型/不同林分类型间的土壤细菌群落组成和多样性有显著差异;而且细菌群落结构在很大程度上受树种和土壤pH值影响 (Heiko et al., 2011),水分含量波动可以改变土壤微生物群落结构 (Drenovsky et al., 2004)。本研究中,7种林分下土壤pH值、含水量、密度、养分含量和细根生物量等的组成和空间分布均有显著差异。如土壤有机质和全氮含量表现为A,G>C>F>B>D>E (向泽宇等,2014),表明不同林木生长对有机碳和全氮含量的影响表现为青海云杉>白桦>山杨>落叶松。不同林分类型间土壤碳含量各异,北美云杉 (Picea sitchensis) 林和西部铁杉 (Tsuga heterophylla) 林的土壤碳含量最高,而美国黄松 (Pinus ponderosa) 林土壤碳含量最低 (Osbert et al., 2004)。不同林分对土壤碱解氮含量的影响也表现为青海云杉>白桦>山杨>落叶松,林分类型影响森林地表氮素的转化 (向泽宇等,2014)。不同林分对细根生物量的影响表现为A,C>E,F,G>B,D,但密度、pH值影响没有表现出明显的规律性。总之,4种不同林木生长对土壤养分积累与分布的影响表现为青海云杉>白桦>山杨>落叶松。阔叶林和针叶林对土壤质量的影响不同 (Saetre, 1999),而且云杉作为青海特有的优势树种对土壤养分的改良及土壤生态的维持具有重要意义 (刘晓敏,2012)。

5 结论本研究利用PLFA法分析青海7种林分类型土壤微生物结构特征变化规律,发现土壤微生物PLFA含量表现为阔叶林>混交林>针叶林,且林分类型越接近其土壤微生物群落组成也越相近;不同林分类型其土壤微生物群落结构多样性存在显著差异。

PLFA法分类水平较低,且无法精确到微生物种的水平,从而限制了对更多土壤微生物群落信息的认识。因此,在今后的研究中应该结合其他检测方法 (如高通量测序技术) 开展土壤微生物群落多样性研究。

| [] |

陈振翔, 于鑫, 夏明芳, 等. 2005. 磷脂脂肪酸分析方法在微生物生态学中的应用. 生态学杂志, 24(7): 828–832.

( Chen Z X, Yu X, Xia M F, et al. 2005. Application of phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis in microbial ecology. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 24(7): 828–832. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

丁访军, 潘忠松, 周凤娇, 等. 2012. 黔中喀斯特地区3种林型土壤有机碳含量及垂直分布特征. 水土保持学报, 26(1): 161–614.

( Ding F J, Pan Z S, Zhou F J, et al. 2012. Organic carbon contents and vertical distribution characteristics of the soil in three forest types of the karst regions in central Guizhou Province. Journal of Soil & Water Conservation, 26(1): 161–614. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

董旭. 2009. 青海省森林资源评价. 安徽农业科学, 37(12): 5727–5728.

( Dong X. 2009. Evaluation of forest Resources in Qinghai Province. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences, 37(12): 5727–5728. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0517-6611.2009.12.163 [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

郭雪莲, 吕宪国, 郗敏. 2007. 植物在湿地养分循环中的作用. 生态学杂志, 26(10): 1628–1633.

( Guo X L, Lü X G, Qie M. 2007. Roles of plant in nutrient cycling in wetland. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 26(10): 1628–1633. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

胡雷, 阿的鲁骥, 字洪标, 等. 2015. 高原鼢鼠扰动及恢复年限对高寒草甸土壤养分和微生物功能多样性的影响. 应用生态学报, 26(9): 2794–2802.

( Hu L, Ade L J, Zi H B, et al. 2015. Effects of plateau zokor disturbance and restoration years on soil nutrients and microbial functional diversity in alpine meadow. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 26(9): 2794–2802. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

蒋婧, 宋明华. 2010. 植物与土壤微生物在调控生态系统养分循环中的作用. 植物生态学报, 34(8): 979–988.

( Jiang J, Song M H. 2010. Review of the roles of plants and soil microorganisms in regulating ecosystem nutrient cycling. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology, 34(8): 979–988. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

李立平, 张佳宝, 朱安宁, 等. 2004. 土壤养分有效性测定及其方法. 土壤通报, 35(1): 84–90.

( Li L P, Zhang J B, Zhu A N, et al. 2004. Soil nutrition availability and testing methods. Chinese Journal of Soil Science, 35(1): 84–90. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

刘波, 胡桂萍, 郑雪芳, 等. 2010. 利用磷脂脂肪酸 (PLFAs) 生物标记法分析水稻根际土壤微生物多样性. 中国水稻科学, 24(3): 278–288.

( Liu B, Hu G P, Zheng X F, et al. 2010. Analysis on microbial diversity in the rhizosphere of rice by phospholipid fatty acids biomarkers. Chinese Journal of Rice Science, 24(3): 278–288. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

刘晓敏. 2012. 祁连山青海云杉林土壤理化性质的空间变异性研究. 兰州: 甘肃农业大学硕士学位论文. ( Liu X M. 2012. Spatial variation of soil physical and chemical properties in Picea crassifolia forest of Qilian Mountain. Lanzhou:MS thesis of Gansu Agricultural University.[in Chinese][in Chinese]) http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10733-1012034327.htm |

| [] |

卢航, 刘康, 吴金鸿. 2013. 青海省近20年森林植被碳储量变化及其现状分析. 长江流域与资源, 22(10): 1333–1338.

( Lu H, Liu K, Wu J H. 2013. Change of carbon storage in forest vegetation and current situation analysis of Qinghai Pronvince in reccent 20 years. Resources & Environment in the Yangtze Basin, 22(10): 1333–1338. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

牛小云, 孙晓梅, 陈东升, 等. 2015. 辽东山区不同林龄日本落叶松人工林土壤微生物、养分及酶活性. 应用生态学报, 26(9): 2663–2672.

( Niu X Y, Sun X M, Chen D S, et al. 2015. Soil microorganisms, nutrients and enzyme activity of Larix kaempferi plantation under different ages in mountainous region of eastern Liaoning Province, China. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 26(9): 2663–2672. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

王长庭, 龙瑞军, 王根绪, 等. 2010. 高寒草甸群落地表植被特征与土壤理化性状、土壤微生物之间的相关性研究. 草业学报, 19(6): 25–34.

( Wang C T, Long R J, Wang G X, et al. 2010. Relationship between plant communities, characters, soil physical and chemical properties, and soil microbiology in alpine meadows. Acta Prataculturae Sinica, 19(6): 25–34. DOI:10.11686/cyxb20100604 [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

王淼, 曲来叶, 马克明, 等. 2014. 罕山土壤微生物群落组成对植被类型的响应. 生态学报, 34(22): 6640–6654.

( Wang M, Qu L Y, Ma K M, et al. 2014. Response of soil microbial community composition to vegetation types. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 34(22): 6640–6654. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

吴则焰, 林文雄, 陈志芳, 等. 2014. 武夷山不同海拔植被带土壤微生物PLFA分析. 林业科学, 50(7): 105–112.

( Wu Z Y, Lin W X, Chen Z F, et al. 2014. Phospholipid fatty acid analysis of soil microbes at different elevation of Wuyi mountains. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 50(7): 105–112. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

向泽宇, 张莉, 张全发, 等. 2014. 青海不同林分类型土壤养分与微生物功能多样性. 林业科学, 50(4): 22–31.

( Xiang Z Y, Zhang L, Zhang Q F, et al. 2014. Soil nutrients and microbial functional diversity of different stand types in Qinghai Province. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 50(4): 22–31. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

杨君珑, 付晓莉, 马泽清, 等. 2015. 中亚热带5种类型森林土壤微生物群落特征. 环境科学研究, 28(5): 720–727.

( Yang J L, Fu X L, Ma Z Q, et al. 2015. Characteristics of soil microbial community in five forest types in mid-subtropical China. Research of Environmental Sciences, 28(5): 720–727. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

易秀, 谷晓静, 侯燕卿, 等. 2011. 陕西省泾惠渠灌区土壤肥力质量综合评价. 干旱区资源与环境, 25(2): 132–137.

( Yi X, Gu X J, Hou Y Q, et al. 2011. Comprehensive assessment on soil fertility quality in Jinghuiqu irrigation district of Shaanxi Province. Journal of Arid Land Resources & Environment, 25(2): 132–137. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

于树, 汪景宽, 李双异. 2008. 应用PLFA方法分析长期不同施肥处理对玉米地土壤微生物群落结构的影响. 生态学报, 28(9): 4221–4227.

( Yu S, Wang J K, Li S Y. 2008. Effect of long-term fertilization on soil microbial community structure in corn field with the method of PLFA. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 28(9): 4221–4227. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

翟辉, 张海, 张超, 等. 2016. 黄土峁状丘陵区不同类型林分土壤微生物功能多样性. 林业科学, 52(12): 84–91.

( Zhai H, Zhang H, Zhang C, et al. 2016. Soil microbial functional diversity in different types of stands in the hilly-gully regions of Loess Plateau. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 52(12): 84–91. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] |

中国科学院南京土壤研究所. 1983. 土壤理化分析. 上海: 上海科学技术出版社.

( Nanjing Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences. 1983. Analysis of soil physical-chemical feature. Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Technology Press. [in Chinese] ) |

| [] | Adair K L, Steve W, Gavin L. 2013. Soil phosphorus depletion and shifts in plant communities change bacterial community structure in a long-term grassland management trial. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 5(3): 404–413. DOI:10.1111/1758-2229.12049 |

| [] | Aneja M K, Sharma S, Fleischmann F, et al. 2006. Microbial colonization of beech and spruce litter-influence of decomposition site and plant litter species on the diversity of microbial community. Microbial Ecology, 52(1): 127–135. DOI:10.1007/s00248-006-9006-3 |

| [] | Baldock J A. 2000. Role of the soil matrix and minerals in protecting natural organic materials against biological attack. Organic Geochemistry, 31(7/8): 697–710. |

| [] | Bardgett R D, Bowman W D, Kaufmann R, et al. 2005. A temporal approach to linking aboveground and belowground ecology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 20(11): 634–41. |

| [] | Bligh E G, Dyer W J. 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Canadian Journal of Biochemistry and Physiology, 37(8): 911–917. DOI:10.1139/o59-099 |

| [] | De Deyn G B, Cornelissen J H C, Bardgett R D. 2008. Plant functional traits and soil carbon sequestration in contrasting biomes. Ecological Letters, 11(5): 516–531. DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01164.x |

| [] | Drenovsky R E, Vo D, Graham K J, et al. 2004. Soil water content and organic carbon availability are major determinants of soil microbial community composition. Microbial Ecology, 48(3): 424–430. DOI:10.1007/s00248-003-1063-2 |

| [] | Frostegård Å, Bååth E, Tunlid A. 1993a. Shifts in the structure of soil microbial communities in limed forests as revealed by phospholipid fatty-acid analysis. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 25(6): 723–730. |

| [] | Frostegård A, Tunlid A, Baath E. 1993b. Phospholipid fatty-acid composition, biomass, and activity of microbial communities from 2 soil types experimentally exposed to different heavy-metals. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 59(11): 3605–3617. |

| [] | Frostegård J, Haegerstrand A, Gidlund M, et al. 1991. Biologically modified LDL increases the adhesive properties of endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis, 90(2/3): 119–126. |

| [] | Gordon D R. 1998. Effects of invasive, non-indigenous plant species on ecosystem processes:lessons from Florida. Ecological Applications, 8(4): 975–989. DOI:10.1890/1051-0761(1998)008[0975:EOINIP]2.0.CO;2 |

| [] | Heiko N, Andrea T, Antje W, et al. 2011. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of bacterial community structure along different management types in German forest and grassland soils. PLoS One, 6(2): e17000. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0017000 |

| [] | Hobbie S E, Ogdahl M, Chorover J, et al. 2007. Tree species effects on soil organic matter dynamics:the role of soil cation composition. Ecosystems, 10(6): 999–1018. DOI:10.1007/s10021-007-9073-4 |

| [] | Joergensen R G, Emmerling C. 2006. Methods for evaluating human impact on soil microorganisms based on their activity, biomass, and diversity in agricultural soils. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 169(3): 295–309. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1522-2624 |

| [] | Joergensen R G, Potthoff M. 2005. Microbial reaction in activity, biomass and community structure after long-term continuous mixing of a grassland soil. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 37(7): 1249–1258. |

| [] | Kimura M, Asakawa S. 2006. Comparison of community structures of microbiota at main habitats in rice field ecosystems based on phospholipid fatty acid analysis. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 43(1): 20–29. DOI:10.1007/s00374-005-0057-2 |

| [] | Meier C L, Bowman W D. 2008. Links between plant litter chemistry, species diversity, and below-ground ecosystem function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(50): 19780–19785. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0805600105 |

| [] | Merila P, Malmivaara-Lamsa M, Spetz P, et al. 2010. Soil organic matter quality as a link between microbial community structure and vegetation composition along a successional gradient in a boreal forest. Applied Soil Ecology, 46(2): 259–267. DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2010.08.003 |

| [] | Ohansen A, Olsson S. 2005. Using phospholipid fatty acid technique to study short term effects of the biological control agent Pseudomonas fluorescens DR54 on the microbial microbiota in barley rhizosphere. Microbiology Ecology, 49(2): 272–281. DOI:10.1007/s00248-004-0135-2 |

| [] | Osbert J S, John C, Beverly E L, et al. 2004. Dynamics of carbon stocks in soils and detritus across chronosequences of different forest types in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Global Change Biology, 10(9): 1470–1481. DOI:10.1111/gcb.2004.10.issue-9 |

| [] | Prescott C E, Grayston S J. 2013. Tree species influence on microbial communities in litter and soil:current knowledge and research needs. Forest Ecology and Management, 309(4): 19–27. |

| [] | Rosenvald K, Kuznetsova T, Ostonen I, et al. 2011. Rhizosphere effect and fine-root morphological adaptations in a chronosequence of silver birch stands on reclaimed oil shale post-mining areas. Ecological Engineering, 37(7): 1027–1034. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2010.05.011 |

| [] | Rutigliano F A, Ascoli R D, Virzo De Santo A. 2004. Soil microbial metabolism and nutrient status in a Mediterranean area as affected by plant cover. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 36(11): 1719–1729. |

| [] | Saetre P, Bååth E. 2000. Spatial variation and patterns of soil microbial community structure in a mixed spruce-birch stand. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 32(7): 909–917. |

| [] | Saetre P. 1999. Spatial patterns of ground vegetation, soil microbial biomass and activity in a mixed spruce-birch stand. Ecography, 22(2): 183–192. DOI:10.1111/eco.1999.22.issue-2 |

| [] | Shillam L, Hopkins D W, Badalucco L, et al. 2008. Structural diversity and enzyme activity of volcanic soils at different stages of development and response to experimental disturbance. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 40(9): 2182–2185. |

| [] | Tscherko D, Hammesfahr U, Zeltner G, et al. 2005. Plant succession and rhizosphere microbial communities in a recently deglaciated alpine terrain. Basic and Applied Ecology, 6(4): 367–383. DOI:10.1016/j.baae.2005.02.004 |

| [] | Vestal J R, White D C. 1989. Lipid analysis in microbial ecology:quantitative approaches to the study of microbial communities. Bioscience, 39(8): 535–541. DOI:10.2307/1310976 |

| [] | Wall D H, Moore J C. 1999. Interactions underground:soil biodiversity, mutualism, and ecosystem process. BioScience, 49(2): 109–117. DOI:10.2307/1313536 |

| [] | Wardle D A, Yeates G W, Nicholson K S, et al. 1999. Response of soil microbial biomass dynamics, activity and plant litter decomposition to agricultural intensification over a seven-year period. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 31(12): 1707–1720. |

| [] | White P S. 1979. Pattern, process and natural disturbance in vegetation. The Botanical Review, 45(3): 229–299. DOI:10.1007/BF02860857 |

| [] | Wilson J B, Agnew A D Q. 1992. Positive-feedback switches in plant communities. Advances in Ecological Research, 23(6): 263–336. |

| [] | Yang Q, Lei A P, Li F L, et al. 2014. Structure and function of soil microbial community in artificially planted Sonneratia apetala and S. caseolaris forests at different stand ages in Shenzhen Bay, China.. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 85(2): 754. |

| [] | Zak D R, Holmes W E, White D C, et al. 2003. Plant diversity, soil microbial communities, and ecosystem function:are there any links?. Ecology, 84(8): 2042–2050. DOI:10.1890/02-0433 |

| [] | Zelles L, Bai Q Y, Rackwits R, et al. 1995. Determination of phospholipid and lipopolysaccharide-derived fatty acids as an estimated of microbial biomass and community structure in soils. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 19(2/3): 115–123. |

| [] | Zhong W H, Gu T, Wang W, et al. 2010. The effects of mineral fertilizer and organic manure on soil microbial community and diversity. Plant and Soil, 326(1): 511–522. |

2017, Vol. 53

2017, Vol. 53