文章信息

- 许建秀, 吴小芹, 叶建仁, 朱丽华, 吴静

- Xu Jianxiu, Wu Xiaoqin, Ye Jianren, Zhu Lihua, Wu Jing

- 抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚的发育和成熟萌发

- Development, Maturation and Germination of Somatic Embryo of Nematode-Resistant Pinus densiflora

- 林业科学, 2017, 53(12): 41-49.

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2017, 53(12): 41-49.

- DOI: 10.11707/j.1001-7488.20171205

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2016-10-23

- 修回日期:2017-09-16

-

作者相关文章

赤松(Pinus densiflora),主要分布于日本、朝鲜、俄罗斯东南部及我国东部,可作庭院、造林的树种,易感染松材线虫(Bursaphelenchus xylophilus)而大量死亡,这对林业生产和生态环境造成了严重破坏(朱丽华等, 2010)。采用常规种苗繁殖技术,繁殖系数低(张守攻等, 2004),选育出的抗病材料难以满足大规模林业生产的需求。为了大量快速繁殖已选优良抗病基因型,在短时间内实现规模化生产,对赤松离体组织培养技术的研究显得尤为重要。

体细胞胚发生具有繁殖系数大、周期短、结构完整、再生率高、不受季节影响等特点(Gupta et al., 1980),是植物大规模无性繁殖的一种主要手段(汪小雄等,2006;Stasolla et al., 2003)。国内外学者已通过体细胞胚发生成功获得50多种针叶树体细胞胚或体细胞胚再生植株(孙志强等,2010),其中火炬松(Pinus taeda)、花旗松(Pseudotsuga menziesii)和辐射松(Pinus radiata)等树种体细胞胚发生已经应用于规模化生产(张守攻等,2004)。Taniguchi(2001)首次对赤松体细胞胚发生进行研究,建立了胚性细胞系并进行了体细胞胚成熟试验,但转化率非常低;随后,Maruyama等(2005;2012)、Shoji等(2006)、Kim等(2014)研究了赤松胚性愈伤组织增殖、体细胞胚成熟、萌发及转化的影响因子,但试验结果存在胚性愈伤组织诱导率低、胚性愈伤组织能力的丧失、体细胞胚成熟与转化率低等情况。国内目前对赤松组织培养器官发生及植株再生有所研究(朱丽华等,2010;李清清,2012),而对赤松体细胞胚发生的研究报道较少(吴静等,2015)。

完整的体细胞胚发生过程包括胚性愈伤组织的形成以及体细胞胚的形成、发育和成熟萌发等阶段。为优化抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚的形成、发育及成熟萌发条件,本试验以抗病赤松的未成熟合子胚诱导形成的胚性愈伤组织为材料,进一步研究了外源激素、糖类、渗透剂、凝固剂及培养方式对抗病赤松体细胞胚发育和成熟萌发的影响,旨在对抗病赤松体细胞胚发生体系进行优化以提高其体细胞胚的质量和数量,从而提高萌发率和植株转化率,为抗病赤松的种质资源保存、体胚苗的大规模工厂化生产提供技术支持。

1 材料和方法 1.1 试验材料抗病赤松未成熟球果于2013年6月采集于江苏句容林场抗松材线虫病赤松种质资源库(2004年2月从日本林木良种繁育中心引种建立),从球果中剥离出未成熟合子胚,在DCR基本培养基(Gupta et al., 1985)上添加2.0 mg·L-1 2, 4-D和1.0 mg·L-1 6-BA成功诱导出具有胚性的愈伤组织(22#-1和13#-1),并已继代培养7次,再经过3次继代培养,将胚性愈伤组织生长状况良好的2个无性系22#-1和13#-1作为体细胞胚发生的材料(吴静等,2015)。

1.2 ABA和PEG8000不同组合对抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚发育和成熟的影响以抗病赤松无性系22#-1胚性愈伤组织为材料进行两因素随机区组试验,A因素脱落酸(ABA)浓度(10,15,20 mg·L-1)、B因素聚乙二醇(PEG) 8000浓度(100,140,180 g·L-1)。将胚性胚柄团(embryonic suspensor mass, ESM)转接至不同组合培养基,每处理30块ESM,重复3次,实时观察体胚的发育及成熟情况。培养基附加肌醇8.0 g·L-1、麦芽糖60 g·L-1、2-(N-吗啡啉)乙磺酸(MES)250 mg·L-1、水解酪蛋白(CH)500 mg·L-1、维生素C(VC)10 mg·L-1、谷氨酰胺(Glu)450 mg·L-1、活性炭(AC)2.0 g·L-1、植物凝胶(phytagel)(Sigma公司)3.0 g·L-1,pH5.8。

抗病赤松体细胞胚诱导、增殖、成熟和萌发试验在培养温度设定为(23±2)℃的组织培养室中暗培养,每2个星期观察1次。正常体细胞胚数(每克愈伤组织形成的正常体细胞胚数,个·g-1)=正常体细胞胚个数/愈伤组织鲜质量;畸形体细胞胚数(每克愈伤组织形成的畸形体细胞胚数,个·g-1)=畸形体细胞胚个数/愈伤组织鲜质量;体细胞胚数(每克愈伤组织形成的体细胞胚数,个·g-1)=体细胞胚个数(包括正常和畸形)/愈伤组织鲜质量。

1.3 碳源种类及浓度对抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚发育和成熟的影响将22#-1的ESM转接在LP基本培养基(Arnold et al., 2010)中,分别添加麦芽糖(20,30,45,60,70 g·L-1)和蔗糖(20,30,45,60,70 g·L-1),每处理30块ESM,重复3次,实时观察体胚的成熟情况。培养基附加ABA 15 mg·L-1、PEG8000 140 g·L-1、肌醇8 g·L-1、MES 250 mg·L-1、CH 500 mg·L-1、VC 10 mg·L-1、Glu 450 mg·L-1、AC 2.0 g·L-1、植物凝胶3.0 g·L-1,pH5.8。体细胞胚培养及测定同1.2。

1.4 肌醇浓度对抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚发育和成熟的影响将22#-1的ESM转接在LP基本培养基中,添加肌醇0,2.0,4.0,6.0,8.0,10.0,16.0 g·L-1,每处理30块ESM,重复3次,实时观察体胚的成熟情况。培养基附加ABA 15.0 mg·L-1、PEG8000 140.0 g·L-1、MES 250.0 mg·L-1、CH 500.0 mg·L-1、VC 10.0 mg·L-1、Glu 450.0 mg·L-1、AC 2.0 g·L-1、植物凝胶3.0 g·L-1,pH5.8。体细胞胚培养及测定同1.2。

1.5 凝固剂对抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚发育和成熟的影响采用2种凝固剂,分别为植物凝胶(phytagel)(Sigma公司)和琼脂(agar powder)(西陇化工公司)。将22#-1的ESM转接在LP基本培养基,分别添加植物凝胶(2.5,3.0,3.5,4.0 g·L-1)和琼脂(6.0,8.0,10.0,12.0 g·L-1),每处理30块ESM,重复3次, 实时观察体胚的成熟情况。体细胞胚培养及测定同1.2。

1.6 不同培养方式下抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚的发育和成熟Ⅰ.液-固增殖-固成熟:取胚性细胞系22#-1和13#-1胚性愈伤组织,转入10.0 mL不含激素DCR液体培养基中,手持剧烈震荡形成体细胞分布均匀且无块状细胞团的悬浮体系(每个细胞团大约有300万个细胞),用1.0 mL的移液枪吸取悬浮液,分散在灭菌后的滤纸上,待水分沥干后,将有培养物的滤纸放入固体增殖培养基,15天之后转入固体成熟培养基。

Ⅱ.固增殖-固成熟:直接用镊子夹取胚性细胞系22#-1和13#-1的胚性愈伤组织于固体增殖培养基上,15天之后转入固体成熟培养基中。

Ⅲ.液-固成熟:取胚性细胞系22#-1和13#-1胚性愈伤组织,转入10.0 mL不含激素DCR液体培养基中,手持剧烈震荡形成体细胞分布均匀且无块状细胞团的悬浮体系,用1.0 mL的移液枪吸取培养好的悬浮液,均匀分散在灭菌后的滤纸上,待水分沥干后,将有培养物的滤纸放入固体成熟培养基中。体细胞胚培养及测定同1.2。

1.7 抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚的萌发及植株再生将体细胞胚22#-1放置于萌发培养基上进行萌发。萌发基本培养基为LP,添加20.0 g·L-1麦芽糖、2.0 g·L-1 AC、3.0 g·L-1植物凝胶,pH5.8。非直射光培养5天左右,再放入直射光下培养15天左右,观察体胚的萌发状况,统计萌发率。然后将萌发的体细胞胚转入WPM基本培养基(Pullman et al., 2005),附加0.1 g·L-1肌醇、1.5 mg·L-1 IBA、15.0 g·L-1蔗糖、0.2 mg·L-1 NAA、7.0 g·L-1卡拉胶(福建省绿麒食品胶体有限公司),每日光照(1 000 lx)下培养16 h、暗培养8 h,持续培养1个月,统计植株转化率。植株转化率(%)=生根的植株数/萌发正常体细胞胚的个数×100%;萌发率(%)=萌发正常体细胞胚的个数/接种体细胞胚个数×100%。

1.8 抗松材线虫病赤松再生植株的移栽待再生植株根伸长2.0 cm左右后移栽,为使幼苗能更好地适应外界的环境,移栽前7天要逐渐把封口膜揭开,移栽的时候要把幼苗根部的培养基洗掉,移栽在苗圃土、珍珠岩和河沙构成1:1:2的基质中。移苗1个月内注意保持温度(23 ℃±2 ℃)、基质湿度(85%±2%)和空气湿度(90%~95%)。4个月后统计移栽成活率。移栽成活率(%)=植株成活的株数/移栽的株数×100%。

1.9 数据处理采用Excel 2003处理试验数据,并用SPSS17.0软件进行方差分析和差异显著性检验,采用Duncan方法进行多重比较。

2 结果与分析 2.1 不同ABA和PEG8000组合对抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚发育和成熟的影响不同ABA和PEG8000浓度对抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚成熟具有显著影响(表 1)。在ABA为15 mg·L-1、PEG为140 g·L-1的浓度组合下,正常体细胞胚数达到171个·g-1,均高于其他处理;当ABA浓度为20 mg·L-1时,正常体细胞胚数都偏低(79个·g-1)。添加适当浓度的ABA可促进体细胞胚单个化并进一步发育成熟。PEG在合适的浓度下,促进体细胞胚的成熟。本试验结果表明PEG对抗病赤松体细胞胚成熟诱导具有显著影响。当PEG浓度达到180 g·L-1时,正常体细胞胚数反而有所下降,可见PEG的使用并非浓度越高正常体细胞胚数就越多,它们之间并不存在正相关。试验表明,ABA浓度为15 mg·L-1和PEG8000 140 g·L-1的组合最适宜抗松材线虫病赤松的体细胞胚成熟。

|

|

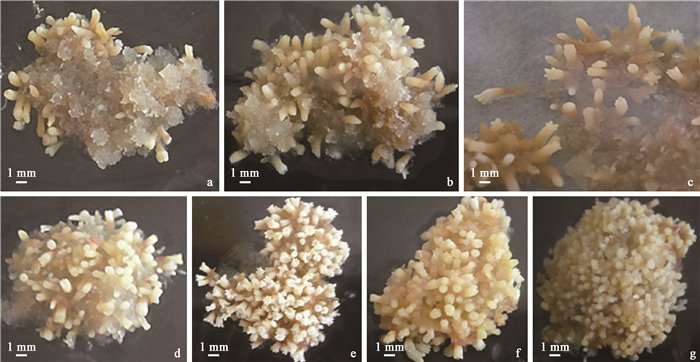

试验研究表明(图 1),在缺乏肌醇的情况下,抗松材线虫病赤松虽能产生子叶胚,但是子叶胚胚头膨大,胚柄短小甚至不能正常发育,胚体短而粗,颜色偏黄,生长不良,均为畸形胚;而且愈伤组织颜色偏褐,结构逐渐紧密,生长状况明显衰退(图 1a)。当加入肌醇时,抗病赤松体细胞胚数明显提高。而肌醇浓度大于8.0 g·L-1时,体细胞胚数剧增,但出现的均为畸形胚,胚头膨大,胚柄短小,生长不佳(图 1f,g)。因此肌醇的最适浓度为8.0 g·L-1,体细胞胚数最高达到179个·g-1(图 1e)。胚性愈伤组织直接放置于添加了肌醇的成熟培养基中,没有在中间过渡培养基中培养,因此可以缩短2~3周培养时间,在8周前后就形成了成熟的子叶胚。

|

图 1 肌醇浓度对抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚发育和成熟的影响 Figure 1 Effect of inositol concentration on somatic embryos maturation in nematode-resistant Pinus densiflora a-g:肌醇浓度分别为0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 16 g·L-1 Inositol concentration is 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 16 g·L-1, respectively. |

不同碳源类型及浓度对抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚成熟的影响存在显著差异,麦芽糖比蔗糖增加抗病赤松正常体细胞胚数的效果明显(P < 0.05)(图 2)。麦芽糖浓度为60 g·L-1时,抗病赤松正常的体细胞胚数达到235个·g-1,而且畸形胚也降到5个·g-1;当麦芽糖和蔗糖浓度升高时,体细胞胚数降低并且畸形胚增多;当麦芽糖和蔗糖浓度低于60 g·L-1时,体细胞胚数少。因此,抗病赤松体细胞胚成熟培养基中,麦芽糖比蔗糖更适宜抗病赤松的体细胞胚发育和成熟,最适浓度为60 g·L-1。

|

图 2 碳源对抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚发育和成熟的影响 Figure 2 Effect of different sugars on somatic embryo maturation in nematode-resistant Pinus densiflora |

试验结果表明,由于培养基中添加了聚乙二醇(PEG),凝固剂琼脂从6.0 g·L-1添加至12.0 g·L-1时,培养基都不能凝固,愈伤组织无法生长,也无子叶胚形成。当加入植物凝胶且浓度为3.0 g·L-1,培养基凝固,软硬适中,产生的子叶胚细长,发育正常,生长良好;当植物凝胶浓度为2.0 g·L-1,子叶胚生长良好,但是培养基较软,不易固定;当植物凝胶浓度增为3.5 g·L-1时,培养基开始偏硬,只出现少量非正常的子叶胚;当植物凝胶浓度增为4.0 g·L-1时,培养基过硬,愈伤组织干燥、颜色发白,未形成子叶胚。因此,在抗病赤松发育成熟阶段宜选用植物凝胶浓度为3.0 g·L-1,可获得质量较好的子叶胚。

2.5 培养方式对抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚发育和成熟的影响采用3种不同培养方式,抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚成熟的时间明显不同,但发育程度基本相同(表 2)。当采用方式Ⅰ(液-固增殖-固成熟)进行培养时,胚性愈伤组织经11~12周能发育成完整结构的成熟体细胞胚,其中22#-1的正常体细胞胚数达到239个·g-1,畸形体细胞胚数降到25个·g-1,且同步化程度最高。当采用方式Ⅱ(固增殖-固成熟)进行培养时,胚性愈伤组织经8~9周能发育成完整结构的成熟体细胞胚,较方式Ⅰ和Ⅲ(液增殖-固成熟)有优势,但正常体细胞胚数较方式Ⅰ有所下降,只有200个·g-1左右,畸形体细胞胚数提高,且同步化程度最低。当采用方式Ⅲ进行培养时,胚性愈伤组织经12~14周才能发育成完整结构的成熟体细胞胚,非常缓慢,且表面水渍化严重,正常体细胞胚数下降到最低,畸形体细胞胚数增至最高。结果表明,方式Ⅰ的正常体细胞胚数最高且畸形体细胞胚数最低,虽成熟时间较方式Ⅱ多了3周左右,但同步化程度高,所需材料少,因此,该方式适合进行抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚成熟试验。

|

|

抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚成熟时,正常子叶胚呈现乳白色或者乳黄色,子叶完全张开,可以清楚地看到有几个子叶,并出现明显的黄色细长胚轴和红色胚根(图 3a1, a2);畸形子叶胚呈现乳白色或者乳黄色,子叶未张开或胚头膨大,胚轴短小甚至不能正常发育,胚根未形成或有红色根点(图 3b1, b2)。

|

图 3 抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚成熟、萌发及植株再生 Figure 3 Somatic embryo maturation, germination and plant regeneration of nematode-resistant Pinus densiflora a1, a2.正常子叶胚; b1, b2.畸形子叶胚; c1, c2.萌发培养基中5天后的体细胞胚; d1, d2, d3.萌发培养基中20天后体细胞胚形成的再生植株; e1, e2. WPM培养基中壮苗的再生植株; f1, f2. WPM培养基中壮苗1个月的再生植株; g1, g2. WPM培养基中壮苗3个月的再生植株; h1.移栽后的体细胞胚苗; h2.移栽后3个月的体细胞胚苗。a1, a2. Normal cotyledon embryo; b1, b2. Abnormal cotyledon embryo; c1, c2. Somatic embryos on germination medium after five days; d1, d2, d3. Plant regeneration from somatic embryogenesis on germination medium after twenty days; e1, e2. Plant regeneration in WPM medium; f1, f2. Plant regeneration in WPM medium after one month; g1, g2. Plant regeneration in WPM medium after three months; h1. Transplanting somatic embryo plantlets; h2. Somatic embryo plantlets three months after transplanting. |

将不同发育阶段产生的成熟体细胞胚轻轻挑出,转至无激素的萌发培养基,散射光培养5天后,体细胞胚子叶由黄白色逐渐变为黄绿色(图 3c1, c2),把子叶胚放在日光灯下培养。在光照之后,正常萌发的子叶逐渐张开,颜色转变为深绿色;胚轴伸长,基部呈现红色微小根尖(图 3d1),后根尖逐渐变为深褐色,根部生长。正常萌发的子叶胚子叶张开,胚轴伸长,基部有微小红色根点(图 3d1),而畸形的子叶胚子叶很小,未张开或者不规则张开,胚轴很短或者几乎没有,基部有一点红色小根点或者没有,基部愈伤化严重(图 3d2, d3)。随后将萌发的体细胞胚转入WPM培养基中,1个月后长出初生针叶,形成再生植株:正常的子叶胚胚轴较长,胚根伸长,1个月后长出初生针叶,嫩白色根长1.0 cm左右(图 3e1, f1);畸形胚胚轴较短,根部的愈伤组织严重(图 3e2, f2)。在WPM壮苗培养基中生长3个月后,正常子叶胚初生针叶继续生长,有的还长出了次生针叶,根部嫩白色,并只有1条主根,主根周围长出许多须根(图 3g1),这时可以直接移栽;而畸形子叶胚在WPM壮苗培养基中生长3个月后,初生针叶虽继续生长,但未见有次生针叶,根部棕褐色,愈伤化严重,有的还长出若干侧根(图 3g2),移栽100株,全部死亡。体细胞胚的萌发率和植株转化率分别为67.2%和46.5%。

2.7 抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚再生植株的移栽正常子叶胚移栽之后,体细胞胚再生植株(图 3h1)生长较幼嫩,移栽3个月后体细胞胚再生植株(图 3h2)都长出次生针叶,根系深入土壤。移栽体细胞胚再生植株为202株,成活株数为66株,移栽成活率为32.7%。

3 讨论体细胞胚成熟是植株能否再生的关键所在,与激素种类和浓度、培养方式、培养基渗透压等有关。ABA已被用于许多树种提高体细胞胚的质量,防止早熟发芽,提高萌发率和转化率(Capuana et al., 1997)。研究表明,渗透压在针叶树体细胞胚的发育过程中起到了重要的作用,一般是利用聚乙二醇(PEG)作渗透剂,来提高培养基的渗透压。很多研究证实在成熟培养基中同时使用ABA和PEG有利于提高体细胞胚的数量和质量(Attree et al., 1989)。黄健秋等(1995a)研究了云南松(Pinus yunnanensis)体细胞胚发生,结果表明PEG与ABA同时使用,几周可形成粗壮的子叶胚。Yildirim等(2006)研究表明,土耳其红松(Pinus brutia)体细胞胚成熟的最适激素组合为80 μmol·L-1 ABA和3.75%PEG。本试验表明,当ABA浓度为15.0 mg·L-1以及PEG8000浓度为140 g·L-1时,正常体细胞胚数达到171个·g-1,均高于其他处理。因此,添加适当浓度的ABA和PEG可促进抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚的个体发育和成熟。此外,培养基中额外添加肌醇、山梨醇等均可产生高渗透压条件,促进体细胞胚发生,防止其早熟萌发,其中以肌醇最为有效(黄健秋等,1995a)。本试验表明,肌醇的浓度为8.0 g·L-1时,抗松材线虫病赤松的正常体细胞胚数最多;肌醇浓度大于8.0 g·L-1时,体细胞胚数剧增,但多数为畸形胚;而当肌醇浓度低于8.0 g·L-1或不添加时,大多为畸形胚,愈伤组织颜色偏褐,结构逐渐紧密,生长状况明显衰退。因此,肌醇的浓度以8.0 g·L-1最适宜抗松材线虫病赤松的体细胞胚成熟。黄健秋等(1995b)及唐巍等(1998)分别将马尾松(Pinus masssoniana)、火炬松早期原胚转入含9 000 mg·L-1肌醇的培养基上培养,形成后期原胚后,再将后期原胚转入成熟培养基中进行体细胞胚成熟;而在本试验中,抗松材线虫病赤松胚性愈伤组织直接放置于添加了肌醇的成熟培养基中,没有在中间过渡培养基中培养,因此可以缩短2~3周培养时间,在8周前后就形成了成熟的子叶胚,加快了抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚发生的进程。

在植物体细胞胚的发育过程中,不同种类及其浓度的碳源起到至关重要的作用。碳源既可以作为能量物质,又可作为渗透调节剂对体细胞胚的发育与成熟起到促进作用。本试验结果显示,麦芽糖比蔗糖更能增加抗松材线虫病赤松体细胞胚的数量。其中麦芽糖浓度为60 g·L-1时,抗病赤松体细胞胚数达到235个·g-1,而且畸形胚也降到最低。当蔗糖和麦芽糖浓度升高时,体细胞胚数降低且畸形胚也较多,这与Li等(1998)和Shoji等(2006)的研究结果一致。

凝固剂在培养基中起固定支撑作用,不同种类凝固剂有可能影响到培养基的物理结构和培养物对营养成分的吸收利用。张巧等(2010)研究表明:以植物凝胶(phytagel)作为凝固剂,提高了陆地棉(Gossypium hirsutum)体细胞胚发生和植株再生频率。本研究以抗松材线虫病赤松22#-1胚性愈伤组织为材料,比较了2种不同凝固剂琼脂(agar powder)和植物凝胶培养基对抗病赤松体细胞胚发生的影响。结果表明:植物凝胶浓度为3.0 g·L-1时,培养基凝固,软硬适中,产生的子叶胚细长,发育正常,生长良好;而成熟培养基中加入PEG8000,琼脂作为凝固剂无法凝固培养基。故植物凝胶对抗松材线虫病赤松胚性愈伤组织的诱导、增殖和体细胞胚成熟均具有良好作用,但考虑到植物凝胶价格因素,在胚性愈伤组织的诱导和增殖过程中可使用较廉价的琼脂,而在体细胞胚成熟和萌发过程中应使用植物凝胶。

植物体细胞胚的培养方式有固体培养、液体悬浮培养、固-液结合培养,培养方式对体细胞胚发生具有显著影响。以往培养方式是松属(Pinus)树种胚性愈伤组织以团块的形式夹取到成熟培养基中,但是此方式需要大量的胚性愈伤组织(Keinonen-Mettälä et al., 1996)。而现在将胚性愈伤组织放入有生长调节剂的悬浮液中生长来最大化地产生体细胞胚(Klimaszewska et al., 2007),每皿(7 cm)胚性愈伤组织起始量在50 mg(Carneros et al., 2009)到500 mg(Maruyama et al., 2007)。本试验对固体培养、液体悬浮培养、固-液结合培养3种培养方式进行了比较,结果表明:液-固增殖-固成熟方式的正常体细胞胚数最高且畸形体细胞胚数最低,虽成熟时间较固增殖-固成熟方式多了3周左右,但同步化程度高,所需材料少,因此,该方式适合进行抗病赤松体胚成熟试验。最近的研究发现,欧洲赤松(Pinus sylvestris)液-固培养比固-固培养能够产生更多良好的细长型的体细胞胚,原因是液-固培养中的胚性愈伤组织在较薄的滤纸上比固-固培养能够更好地吸收营养物质并产生大量的体细胞胚(Lelu-Walter et al., 2008)。

植物体细胞胚的萌发与植株再生培养基的调节有利于提高萌发率和植株转化率。齐力旺等(2004)研究表明附加IBA和NAA的萌发培养基可以促进华北落叶松(Larix principis-rupprechtii)体细胞胚根的发生。本试验研究发现,附加1.5 mg·L-1 IBA和0.2 mg·L-1 NAA的WPM植株再生培养基有利于促进抗松材线虫病赤松根的发生,体细胞胚的萌发率和植株转化率高,分别为67.2%和46.5%。研究中发现,仅挑出质量好的体细胞胚进行萌发是能够成功获得良好的植株再生苗的关键因素之一(Aronen et al., 2009)。本试验中,高质量的体细胞胚可以转化为良好的植株再生苗,而低质量的体细胞胚最终移栽不成活,这表明高质量的体细胞胚能够提高体细胞胚的萌发率和植株转化率。此外在本试验中再生植株壮苗利用WPM培养基,3个月之后再生植株根伸长3.0 cm左右,这表明WPM培养基能促进植株生长和根的进一步伸长。

4 结论将抗松材线虫病赤松胚性愈伤组织置于15.0 mg·L-1ABA、140 g·L-1 PEG8000、8.0 g·L-1肌醇、60 g·L-1麦芽糖、3.0 g·L-1植物凝胶的LP培养基上,以液-固增殖-固成熟培养方式培养,成功获得了高质量的体细胞胚和再生植株,体细胞胚的萌发率和植株转化率分别为67.2%和46.5%,再生植株移栽3个月后成活率为32.7%,为抗病赤松的大规模繁殖和工厂化生产提供了技术支持。

黄健秋, 卫志明. 1995a. 云南松成熟胚的体细胞胚胎的发生研究[J]. 实验生物学报, 28(4): 371-379. (Huang J Q, Wei Z M. 1995a. Somatic embryogenesis from callus of mature Yunnan pine embryos[J]. Acta Biologiae Experimentalis Sinica, 28(4): 371-379. [in Chinese]) |

黄健秋, 卫志明. 1995b. 马尾松成熟合子胚的体细胞胚胎发生和植株再生[J]. 植物学报, 37(4): 289-294. (Huang J Q, Wei Z M. 1995b. Somatic embryogenesis and plantlet regeneration from callus of mature zygotic embryos of Masson pine[J]. Acta Botanica Sinica, 37(4): 289-294. [in Chinese]) |

李清清. 2012. 黑松和赤松组织培养快繁技术研究. 南京: 南京林业大学硕士学位论文. (Li Q Q. 2012. Study on tissue culture of Pinus thunbergii and Pinus densiflora. Nanjing:MS thesis of Nanjing Forestry University.[in Chinese]) |

齐力旺, 韩一凡, 韩素英, 等. 2004. 麦芽糖、NAA及ABA对华北落叶松体细胞胚成熟及生根的影响[J]. 林业科学, 40(1): 52-57. (Qi L W, Han Y F, Han S Y, et al. 2004. Effects of malt, NAA and ABA to somatic maturation and radicle rooting of Larix principis-rupprechtii[J]. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 40(1): 52-57. DOI:10.11707/j.1001-7488.20040109 [in Chinese]) |

孙志强, 孙占育, 席梦利. 2010. 针叶树体细胞胚胎发生研究进展[J]. 林业科技开发, 24(4): 1-5. (Sun Z Q, Sun Z Y, Xi M L. 2010. Research progress in somatic embryogenesis of conifer[J]. China Forestry Science and Technology, 24(4): 1-5. [in Chinese]) |

唐巍, 欧阳藩, 郭仲琛. 1998. 火炬松胚性愈伤组织诱导和植株再生的研究[J]. 林业科学, 34(3): 115-119. (Tang W, Ouyang F, Gong Z C. 1998. Studies on embryogenic callus induction and plant regeneration in loblolly pine[J]. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 34(3): 115-119. [in Chinese]) |

汪小雄, 卢龙斗, 郝怀庆, 等. 2006. 松杉类植物体细胞胚发育机理的研究进展[J]. 西北植物学报, 26(9): 1965-1972. (Wang X X, Lu L D, Hao H Q, et al. 2006. Research advances about developmental mechanism of somatic embryos in conifers[J]. Acta Botanica Boreali-Occidentalia Sinica, 26(9): 1965-1972. [in Chinese]) |

吴静, 朱丽华, 许建秀, 等. 2015. 抗松材线虫病赤松胚性愈伤组织的诱导及增殖[J]. 南京林业大学学报:自然科学版, 39(1): 17-21. (Wu J, Zhu L H, Xu J X, et al. 2015. Initiation and proliferation of nematode-resistant Pinus densiflora[J]. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University:Natural Sciences Edition, 39(1): 17-21. [in Chinese]) |

张巧, 汪静儿, 林君, 等. 2010. 不同凝固剂对陆地棉体细胞胚胎发生和植株再生的影响[J]. 棉花学报, (1): 3-9. (Zhang Q, Wang J E, Lin J, et al. 2010. Effects of different gelling agents on the somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration in upland cotton[J]. Cotton Science, (1): 3-9. [in Chinese]) |

张守攻, 邱宏伟, 韩素英, 等. 2004. 落叶松树种的体细胞胚胎发生与规模化技术体系[J]. 中国生物工程杂志, 24(6): 28-33. (Zhang S G, Qiu H W, Han S Y, et al. 2004. The system of embryos rapid multiplication by special bioreactor on somatic embryogenesis of Larix species[J]. Progress in Biotechnology, 24(6): 28-33. [in Chinese]) |

朱丽华, 吴小芹, 戴培培, 等. 2010. 赤松离体培养植株再生体系的建立[J]. 南京林业大学学报:自然科学版, 34(2): 11-14. (Zhu L H, Wu X Q, Dai P P, et al. 2010. In vitro plantlet regeneration from seedling explants of Pinus densiflora[J]. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University:Natural Sciences Edition, 34(2): 11-14. [in Chinese]) |

Arnold S, Eriksson T. 2010. A revised medium for growth of pea mesophyll protoplasts[J]. Physiologia Plantarum, 39(4): 257-260. |

Aronen T, Pehkonen T, Ryynänen L. 2009. Enhancement of somatic embryogenesis from immature zygotic embryos of Pinus sylvestris[J]. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 24(5): 372-383. DOI:10.1080/02827580903228862 |

Attree S M, Dunstan D I, Fowke L C. 1989. Initiation of embryogenic callus and suspension cultures, and improved embryo regeneration from protoplasts, of white spruce (Picea glauca)[J]. Canadian Journal of Botany, 67(6): 1790-1795. DOI:10.1139/b89-227 |

Capuana M, Debergh P C. 1997. Improvement of the maturation and germination of horse chestnut somatic embryos[J]. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 48(1): 23-29. DOI:10.1023/A:1005890826431 |

Carneros E, Celestino C, Klimaszewska K, et al. 2009. Plant regeneration in Stone pine (Pinus pinea L.) by somatic embryogenesis[J]. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 98(2): 165-178. DOI:10.1007/s11240-009-9549-3 |

Gupta P K, Durzan D J. 1985. Shoot multiplication from mature trees of Douglas-fir(Pseudotsuga menziesii) and sugar pine(Pinus lambertiana)[J]. Plant Cell Reports, 4: 177-179. DOI:10.1007/BF00269282 |

Gupta P K, Pullman G, Timmis R, et al. 1980. Forestry in the 21st century:the biotechnology of somatic embryogenesis[J]. Journal of Endocrinology, 123(3): 441-444. |

Keinonen-Mettälä K, Jalonen P, Eurola P, et al. 1996. Somatic embryogenesis of Pinus sylvestris[J]. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 11(1/4): 242-250. |

Kim Y W, Moon H K. 2014. Enhancement of somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration in Japanese red pine (Pinus densiflora)[J]. Plant Biotechnology Reports, 8(3): 259-266. DOI:10.1007/s11816-014-0319-2 |

Klimaszewska K, Trontin J F, Becwar M R, et al. 2007. Recent progress in somatic embryogenesis of four Pinus spp[J]. Tree For Sci Biotechnol, 1(1): 11-25. |

Lelu-Walter M A, Bernier-Cardou M, Klimaszewska K. 2008. Clonal plant production from self-and cross-pollinated seed families of Pinus sylvestris (L.) through somatic embryogenesis[J]. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 92(1): 31-45. |

Li X Y, Huang F H, Murphy J B, et al. 1998. Polyethylene glycol and maltose enhance somatic embryo maturation in loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.)[J]. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Plant, 34(1): 22-26. |

Maruyama E, Hosoi Y, Ishii K. 2005. Propagation of Japanese red pine (Pinus densiflora Zieb. et Zucc.) via somatic embryogenesis[J]. Prop Ornam Plants, 5: 199-204. |

Maruyama E, Hosoi Y, Ishii K. 2007. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration in yakutanegoyou, Pinus armandii Franch. var. amamiana (Koidz.) Hatusima, an endemic and endangered species in Japan[J]. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Plant, 43(1): 28-34. |

Maruyama T E, Hosoi Y. 2012. Post-maturation treatment improves and synchronizes somatic embryo germination of three species of Japanese pines[J]. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 110(1): 45-52. DOI:10.1007/s11240-012-0128-7 |

Pullman G S, Johnson S, Tassel S V, et al. 2005. Somatic embryogenesis in loblolly pine(Pinus taeda) and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii):improving culture initiation and growth with MES pH buffer, biotin, and folic acid[J]. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 80(1): 91-103. DOI:10.1007/s11240-004-9099-7 |

Shoji M, Sato H, Nakagawa R, et al. 2006. Influence of osmotic pressure on somatic embryo maturation in Pinus densiflora[J]. Journal of Forest Research, 11(6): 449-453. DOI:10.1007/s10310-006-0227-6 |

Stasolla C, Yeung E C. 2003. Recent advances in conifer somatic embryogenesis:improving somatic embryo quality[J]. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 74(1): 15-35. DOI:10.1023/A:1023345803336 |

Taniguchi T. 2001. Plant regeneration from somatic embryos in Pinus thunbergii (Japanese black pine) and Pinus densiflora (Japanese red pine)[J]. Progress in Biotechnology, 18: 319-324. DOI:10.1016/S0921-0423(01)80088-5 |

Yildirim T, Kaya Z, Isik K. 2006. Induction of embryogenic tissue and maturation of somatic embryos in Pinus brutia TEN[J]. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 87(1): 67-76. DOI:10.1007/s11240-006-9137-8 |

2017, Vol. 53

2017, Vol. 53