文章信息

- 姚兰, 崔国发, 易咏梅, 黄永涛, 冯广, 刘峻城, 艾训儒

- Yao Lan, Cui Guofa, Yi Yongmei, Huang Yongtao, Feng Guang, Liu Juncheng, Ai Xunru

- 湖北木林子保护区大样地的木本植物多样性

- Species Diversity of Woody Plants in Mulinzi Nature Reserve of Hubei Province

- 林业科学, 2016, 52(1): 1-9

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2016, 52(1): 1-9.

- DOI: 10.11707/j.1001-7488.2016-1-1

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2015-02-05

- 修回日期:2015-12-13

-

作者相关文章

2. 湖北民族学院林学园艺学院 恩施 445000

2. School of Forestry and Horticulture, Hubei University for Nationalities Enshi 445000

物种多样性是群落生态学研究的热点之一,是现代生态学十分重要的内容(Bachman et al., 2004;Brehm et al., 2007; Ashton et al., 2015),物种多样性是物种丰富度和分布均匀性的综合反映,体现了群落或生态系统的组成结构、组织水平、发展阶段、稳定程度和生境差异(阎海平等,2001; 茹文明等,2006; 马姜明等,2007; Grman et al., 2014;Hudson,2014),不仅可以反映群落在组成、结构、功能和动态等方面的特性,也可反映不同自然地理条件与群落的相互关系(Pimm et al., 2004; Gotmark et al., 2008; Fraser et al., 2014)。任何群落或生态系统都有物种多样性特征,而这种特征正是群落或生态系统功能维持的基础(Tilman et al., 1994; Grime,1997)。

限于监测条件和数据积累缺乏等原因,以往物种多样性研究大都作为群落生态学特征分析的一部分,很少关注其动态和空间异质性等。20 世纪80年代以来,生物多样性监测越来越受到学术界和生物多样性保护机构的重视,森林动态监测样地(大样地)已成为生物多样性监测与研究的重要平台;而且,有关物种多样性较深入的研究分析也多以大样地为基础探索其分布格局、形成与维持机制(叶万辉等,2008)。大样地于1975 年在巴拿马的巴洛克罗拉多岛首次建立,经过多年努力,目前全球已有59 个森林生物多样性动态监测样地(Anderson-Teixeira et al., 2015)。我国大样地建设开始于2004年,分别在长白山、古田山、宝天曼、八大公山、鼎湖山和西双版纳等地建立了多个20 ~ 25 hm2 大型固定样地,用于监测我国温带针阔混交林、亚热带常绿阔叶林、南亚热带常绿阔叶林和热带季节雨林的生物多样性动态。大样地的建设有效监测了物种的时空分布,为研究物种多样性的维持机制、物种空间分布格局、群落动态等提供了重要的研究平台,并取得了森林生物多样性形成与维持等方面的大量成果(Condit,1995; Condit et al., 2002; 2006; Hooper et al., 2004; Hubbell,2006)。由于我国地跨热带到寒温带,而且即使同一温度带或同一种森林类型,其分布范围也相对广阔,因此,需要多点布设固定监测样地,形成对森林类型全面的生物多样性监测。

亚热带常绿阔叶林是我国亚热带地区最具代表性的植被类型,也是全球同纬度地区结构最复杂、生产力最高、生物多样性最丰富的地带性植被类型,对维护区域生态环境和全球碳平衡等具有重要作用。地带性亚热带常绿阔叶林在纬度偏北或海拔偏高处,往往会由于适应低温环境而出现不同程度的落叶成分,从而形成亚热带常绿落叶阔叶混交林。亚热带常绿落叶阔叶混交林是鄂西南地区最具代表性的植被类型,而木林子国家级自然保护区是鄂西南亚热带常绿落叶阔叶混交林保存最为完好的地区。有关亚热带常绿阔叶林的群落结构与物种多样性已有大量研究,基于大样地的亚热带常绿阔叶林研究也开展了大量工作;然而,对于亚热带常绿落叶阔叶混交林群落的研究还不多,而对其基于大样地的物种多样性研究还没有开展过。木林子国家的自然保护区15 hm2 森林动态监测样地是我国林业部门在亚热带常绿落叶阔叶混交林中建立的首个动态监测样地,是对中国森林生物多样性动态监测样地和我国森林生态系统监测网络的有益补充。由于其地处我国偏西部的亚热带地区,与古田山和鼎湖山形成三角之势,完善了亚热带森林生物多样性动态监测网络。本研究参照CTFS 大样地建设与监测技术规范,于2014 年在湖北木林子国家级自然保护区亚热带常绿落叶阔叶混交林中建立15 hm2 森林动态监测样地,调查并鉴定样地内DBH≥1 cm 的所有木本植物,分析其物种多样性特征,以期为亚热带常绿阔叶林区生物多样性的保育与管理提供依据。

1 研究区概况木林子国家级自然保护区地处武陵山余脉,位于湖北省恩施土家族苗族自治州鹤峰县北部(109°59'—110° 17' E,29° 55'—30° 10' N),海拔1 100 ~ 2 095.6 m,面积20 838 hm2。该地区属中亚热带湿润季风气候,年均气温15.5 ℃,绝对高温39 ℃,绝对低温- 17.1 ℃,年均降水量1 700 ~1 900 mm,年均相对空气湿度82%,全年无霜期270 ~ 279 天。自然土壤沿海拔由低到高有山地黄壤、山地黄棕壤和山地棕壤。与典型的亚热带常绿阔叶林区域相比,木林子保护区的海拔相对较高,因此,为了适应低温环境,落叶树种也比典型的亚热带常绿阔叶林多,代表性植被类型为亚热带常绿落叶阔叶混交林。

2 研究方法 2.1 样地设置与植被调查在木林子国家级自然保护区试验区内,选择地势相对平缓、内部地形相对一致的区域,按照CTFS大样地建设与监测技术规范,建立东西长300 m、南北长500 m 的15 hm2 固定样地。采用实时动态测量仪将15 hm2 大样地划分为375 块20 m × 20 m 的样地,样地4 角用水泥桩作永久标记。在每块20 m × 20 m样地内用插值法细分为4 个10 m ×10 m和16 个5 m × 5 m 小样方。

野外调查以20 m × 20 m 样地为树种编号单元,以大样地的西南角为坐标原点进行样地编号。调查过程中对胸径(DBH)≥1 cm 的所有树木进行每木调查,记录物种名称、树高、胸径、坐标、是否萌生,并挂牌和涂刷油漆标记;现场不能确定名称的物种,进行标本采集,请专业人员进行鉴定。由于该区域植被覆盖度较高,林下草本较少且种类贫乏,同时考虑便于与国内外大样地的结果进行比较,因此,以木本植物为主要调查和研究对象,草本植物不在研究范围内。所有野外样地建立及调查内容和方法均按BCI 的标准和技术规范执行。

2.2 数据处理与分析基于野外调查数据,分别按1,10和30 cm 起测径级统计大样地科、属、种、个体多度等物种组成情况,并计算不同起测径级范围单位面积内(hm2)的科、属、种、个体多度。

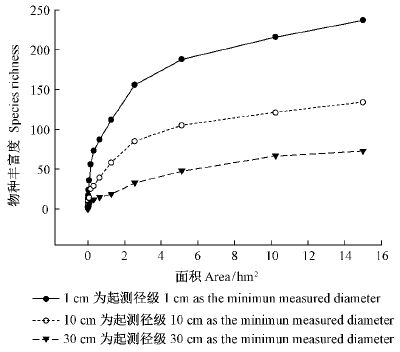

分别统计3 个起测径级范围的物种数量随取样面积增加的变化情况,统计基础面积为1 个样方面积(5 m × 5 m),每次面积增加数值为前1 次面积的1 倍,即采用翻倍的形式进行面积增加。根据取样面积和相应的物种数量绘制物种- 面积曲线。

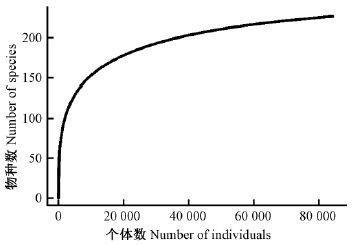

在统计物种多度时,按照物种个体多度,分别统计个体多度≥1 000 株·hm - 2和个体多度< 1 株·hm - 2的物种数量。同时将物种按照个体多度从高到底进行排序,绘制物种- 多度曲线。

科重要值(FIV)计算公式为:FIV =(RB + RD +RA)/3,RB 为相对多样性,是指一个科的物种数占总物种数的百分比,RD 为相对优势度,RA 为相对多度; 物种重要值IV 计算公式为:IV =(RF + RD +RA)/3,RF 为相对频度,RD 为相对显著度。根据科和物种的重要值确定大样地中的优势科与优势种。

根据野外调查数据中物种萌生情况,分别按1,10和30 cm 起测径级统计大样地萌生物种的科、属、种、个体多度和胸高断面积,并计算不同起测径级范围萌生物种的科、属、种、个体多度占相应起测径级范围所有物种科、属、种、个体多度的比例。

所有数据均采用SPSS19.0 软件进行统计和分析,采用Sigmaplot10.0 软件作图。

3 结果与分析 3.1 树种组成分析木林子国家级自然保护区15 hm2 固定监测样地中,共有木本植物228 种(84 189 株),分属于112属61 科,其中以10 cm 为起测径级的木本植物130种11 863 株,分属于71 属44 科; 以30 cm 为起测径级的木本植物67 种1 721 株,分属于40 属29 科(表 1)。

|

|

以1 cm 为起测径级时,样地内平均每公顷木本植物为97 种,个体数量为5 612.6 株·hm - 2 ; 以10cm 为起测径级时,平均每公顷木本植物为49 种,个体数量为791.1 株·hm - 2 ; 以30 cm 为起测径级时,平均每公顷木本植物20 种,个体数量114.7 株·hm - 2。样地内所有物种胸高断面积为551.71 m2,平均每公顷胸高断面积为36.78 m2 ; 以10 cm 为起测径级时的胸高断面积为471.67 m2,平均每公顷胸高断面积为31.40 m2 ; 以30 cm 为起测径级时的胸高断面积为222.70 m2,平均每公顷胸高断面积为14.80 m2(表 1)。

3.2 物种-面积曲线与物种-多度曲线样地内不同起测径级树木的物种- 面积曲线有所差别,以1 cm和10 cm 为起测径级的在0 ~ 3 hm2范围内物种数快速增加,随后增加趋势减弱,在6hm2 时包含的树种数均超过了总物种数的80% ; 以30 cm 为起测径级的树木在0 ~ 0.2 hm2 范围内树种数快速增加,随后增加趋势减弱,在8 hm2 时包含的树种数超过了总物种数的80%(图 1)。

|

图1 物种- 面积曲线 Fig.1 Curve of species richness against area |

类似于物种- 面积曲线,物种数量也随着样地内植物个体数量的增加而增加,并且存在着明显的拐点。植物个体数量低于10 000 时,物种数量随着多度的增加迅速增加,但当植物个体多度大于20000 时,物种数量随着多度的增加速度放缓,并逐渐趋于稳定(图 2)。

|

图2 物种- 多度曲线 Fig.2 Curve of species against richness |

样地内个体数量超过1 000 的物种有18 种,占样地所有物种数的7.89%,但个体数量之和占样地总个体数量的70.63%。在这18 个物种中,个体数量超过10 000 的物种仅有翅柃(Eurya alata)1 种(表 2),个体数量超过5 000 的物种有2 种:多脉青冈(Cyclobalanopsis multinervis)和小叶青冈(C.myrsinifolia),个体数量为2 000 ~ 5 000 的物种有8种,而个体数量低于2 000 的物种有7 种(表 2)。

|

|

按照 Hubbell 等(1986)关于稀有种的定义,平均每公顷个体数少于1 株的种被认为是稀有种。据此定义,木林子自然保护区样地内有116 种稀有物种,占物种总数的50.88%,超过样地总物种数的一半,但个体数量仅占总个体数量的0.14%。其中,个体数量为1 的物种有28 种,分别占物种总数及稀有种的12.28%和24.14%。

3.4 优势科与物种根据对调查数据的统计,样地中重要值最大的科为壳斗科(Fagaceae),包含19 种物种,个体数量达到17 908 株,重要值为0.239;其次为山茶科(Theaceae),尽管仅包含5 种物种,但个体数量高达21 035 株,重要值为0.113。蔷薇科(Rosaceae)是样地内物种最丰富的科,有27 种物种,重要值排名第3;桦木科(Betulaceae)包含5 种物种,重要值排名第4;重要值排名前10 位的所有科共包含108 种物种,占样地总物种数的47.37%,接近一半; 而个体数量达到75 130 株,占样地总个体数量的89.24%(表 3)。

|

|

在所有61 科中,蔷薇科所含物种最多,为27种,分属于12 个属; 其次为壳斗科,包含19 种物种,分属于6 个属; 随后樟科(Lauraceae),含有14种物种; 杜鹃花科(Ericaceae)含有12 种物种,分属于6 个属;其余科所含物种数均低于10。

在所有物种中,翅柃的重要值最高,达0.108,其相对多度、相对频度也最高(表 4),这在表 2 中也有所体现。重要值排名第2和第3 的分别为多脉青冈和川陕鹅耳枥(Carpinus fargesiana)。重要值排名前10 位的物种中,壳斗科共包含4 种物种,合计重要值0.218,山茶科共包含1 种物种,合计重要值0.108,山矾科(Symplocaceae)包含2 种物种,但合计重要值仅0.048,其余科均仅含1 种物种。

|

|

在木林子国家级自然保护区15 hm2 固定监测样地中,共含有木本植物萌生个体18 880 株,属于137 种76 属42 科。其中,以10 cm 为起测径级的萌生木本植物64 种,分属于43 属26 科,共计1 073株; 以30 cm 为起测径级的萌生木本植物17 种,分属于15 属和9 科,共计46 株(表 5)。

|

|

尽管所有萌生个体(DBH≥1 cm)仅占样地总个体数量的22.43%,但萌生物种数则超过了总物种数的50%,而这些物种所属科、属数分别高达总数的65.6%和62.8%。样地中所有以10 cm为起测径级的物种中,有超过1 /4 的物种出现萌生现象,这些物种所属科、属数分别占总数的40.6%和35.54% ;样地中所有以30 cm 为起测径级的物种中,有7.46% 的物种出现萌生现象,这些物种所属科、属数分别占总数的14.1%和12.4%。然而,3个不同起测径级范围的萌生物种胸高断面积均较低,占相应起测径级范围内总胸高断面积的比例均不足8%(表 5)。

4 讨论 4.1 物种多度研究显示,木林子国家级自然保护区15 hm2 常绿落叶阔叶混交林固定监测样地物种多度高于我国长白山(52 种)(郝占庆等,2008)、古田山(159 种)(祝燕等,2008)、鼎湖山(210 种)(叶万辉等,2008)大样地,但明显低于西双版纳(468 种)(兰国玉等,2008),同样也低于世界大多数热带雨林大样地(Condit et al., 1996; 2005; Bunyavejchewin et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2002; Valencia et al., 2004)。与相近面积的样地相比,木林子样地物种总数低于菲律宾Palanan 样地(335 种)(Condit et al., 2005),而高于波多黎各的Luquillo 样地(140 种)(Thompson et al., 2002)。在单位面积(hm2)物种数量上,木林子样地同样高于长白山(25 hm2 物种数仅52 种)(郝占庆等,2008)、印度Mudumalai 样地(25.6 种)(Sukumar et al., 1992)及波多黎各的Luquillo 样地(77.6 种)(Thompson et al., 2002),而低于西双版纳大样地(216.5 种)(兰国玉等,2008)、喀麦隆Korup样地(235.1 种)(Condit et al., 2005)、马来西亚Pasoh 样地(496.5 种)(Condit et al., 1999)和Lambir样地(618.1 种)(Lee et al., 2002)。从样地总物种数及单位面积物种数上看,木林子保护区常绿落叶阔叶混交林样地均高于温带样地,而低于热带雨林或季节雨林样地,这与物种数量随纬度的升高而降低相符合。研究也发现,木林子常绿落叶阔叶混交林样地物种数量与同为亚热带的古田山和鼎湖山相比同样较高,这可能与样地建立地点的地形有关。复杂的地形形成多样的微生境,提供更多生态位,必然会容纳更多的物种种类。此外,较高的稀有种比例也证实了上述说法,成就了其较高的物种多度。另外,由于低温等特殊环境,较多落叶物种出现,从而使这一区域的物种多样性得到了补充和丰富。

4.2 优势物种研究显示,从重要值分析,翅柃、多脉青冈、川陕鹅耳枥和小叶青冈这4 个物种是木林子常绿落叶阔叶混交林样地中最主要的物种。样地中,个体数量超过5 000 的仅有翅柃、多脉青冈和小叶青冈3 个物种。在这3 个物种中,翅柃属于山茶科,小叶青冈和多脉青冈则属于壳斗科,这2 个科也正是常绿阔叶林的代表性科(吴征镒,1980),这在科的重要值统计中也进一步得到了证实(表 3)。在这3 个物种中,尽管翅柃个体数量、重要值均最高,但其平均树高较低,绝大多数低于10 m,说明翅柃处于群落林冠的下层。尽管小叶青冈和多脉青冈个体数量少,但其树体高大(最大树高为30 m),大径级树木(DBH≥60 cm)所占比例较高,成为群落林冠上层树种。

4.3 萌生物种多样性作为森林更新的一种方式(Bond et al., 2001;Moreira et al., 2012),萌生由于其高生长速率、高效利用养分资源(Vieira et al., 2006)及较强的抗干扰能力(Vesk et al., 2004)而得到了越来越多的重视。具有竞争优势的萌生植株,对群落恢复(Miller et al., 1998)、群落抗干扰能力(Bellingham et al., 2000)、群落动态维持(Bond et al., 2001)、解释物种多样性和进化(Bond et al., 2003a)、预测全球变化下的植被迁移(Bond et al., 2003b; Bradley et al., 2007)等具有重要功能。苏建荣等(2012)对季风常绿阔叶林的研究发现,在群落恢复初期,萌生物种比例接近45%,而在西双版纳刀耕火种轮歇地和哀牢山湿性常绿阔叶林中萌生比例分别高达68.97%和69.90%(林露湘等,2002; 陈沐等,2008)。萌枝更新极大影响着受损群落的种类组成和结构(Calvo et al., 2002)。Pausas 等(1999)研究发现,萌枝对群落的物种丰富度、种面积曲线等都具有重要影响。具有萌枝能力的物种会以萌枝方式对干扰做出响应,占领失去的空间,留给群落外种类定居的机会很少。因此,选择的后果是该立地上保留了萌枝力强的物种(Grant et al., 1999),从而在一定程度上降低了群落内的物种周转率(Kruger et al., 2001)。相反,由那些不具备萌枝能力以及经过多次干扰而丧失萌枝能力的种类组成的植物群落,则没有“驻留生态位”的选择权,给群落外其他物种迁入的机会,也从根本上改变了原来的群落结构和种类组成特征(Kruger et al., 2001)。因此,萌生种类的多少直接影响群落的自我平衡调节能力和稳定性(Vesk,2006)。

影响物种萌生的因素很多,干扰其最主要的因素之一。尽管几乎所有物种都具有萌生能力,但萌生主要发生于干扰生态系统中(Luoga et al., 2004)。本研究中,尽管固定样地建立在保护区内,但保护区建立较晚(1995 年建立);并且,在保护区建立之前,该区域在20 世纪初期曾遭受过严重人为干扰;同时,该区域也是附近居民区主要的薪炭林区,特别是在样地东北方,因此,萌生物种及个体较多成为必然。在干扰后的森林生态系统中,由于萌生具有生长快、不受立地条件影响等优点,同时避免了实生需要种子输入、土壤条件、湿度条件等苛求,因此萌生更容易。此外,萌生同样受环境条件的影响,如光照、水分、营养状况等。光照是影响植物萌生能力的主要环境因子之一(苏建荣等,2012),许多研究表明,光照可以促进物种萌生(Rydberg,2000; Kubo et al., 2005)。随着光照的增加,植物体内可移动的碳水化合物含量升高,植物萌生能力逐渐增强;光照减弱,则会降低萌生物种的种类及数量。此外,萌生也受群落演替影响,一般来说,具有较多萌生物种的群落处于演替初级阶段。正如前文所说,萌生主要发生在干扰生态系统中,而干扰后的生态系统多数处于演替初级阶段。这在以往的大量野外调查中同样得到了验证,老龄林或原始林中萌生物种比例相对较低(Luoga et al., 2004)。当然,并非所有物种在干扰后都能产生萌生现象,这一方面与干扰本身有关,另一方面也与物种的生态对策有关。对一些阳性物种,由于其在生活史过程中会产生大量种子,群落受到干扰后,其可通过种子进行更新,并能迅速生长;但对群落内的顶级或阴性物种来说,通过萌生可大大缩短演替时间,保持其在群落中的优势或主导地位。同样,其他因素如残留体特征、树体大小、种间竞争等均会影响物种萌生(阎恩荣等,2005),物种萌生是多因素共同作用的结果。

5 结论木林子国家级自然保护区常绿落叶阔叶混交林物种相对丰富,共有木本植物228 种84 189 株,分属于112 属61 科。不同起测径级树木的物种- 面积曲线、物种- 多度曲线斜率均存在由高到低的变化过程,最后逐渐平缓。稀有种是木林子国家级自然保护区常绿落叶阔叶混交林物种组成的主要组分,占所有物种的50.88%。木林子常绿落叶阔叶混交林中最主要的物种包括翅柃、多脉青冈、川陕鹅耳枥、小叶青冈,主要科为山茶科和壳斗科。木林子常绿落叶阔叶混交林中60.1% 的物种具有萌生现象,胸径大于10 cm 的物种中也有28.07% 出现萌生现象,说明木林子常绿落叶阔叶混交林中许多物种依靠萌生进行种群维持。

| [1] |

陈沐, 房辉, 曹敏. 2008. 云南哀牢山中山湿性常绿阔叶林树种萌生特征研究. 广西植物, 28(5):627-632. (Chen M, Fang H, Cao M.2008. Sprouting characteristics of sprouted woody plants in the mid-mountain humid evergreen broad-leaved forest on Ailao Mountain, Yunnan Province. Guihaia, 28(5):627-632.[in Chinese])(  1) 1)

|

| [2] |

郝占庆, 李步杭, 张健,等. 2008. 长白山阔叶红松林样地(CBS):群落组成与结构. 植物生态学报, 32(2):238-250. (Hao Z Q, Li B H, Zhang J, et al. 2008. Broad-leaved koreanpine(Pinus koraiensis) mixed forest plot in Changbaishan(CBS) of China:community composition and structure. Journal of Plant Ecology, 32(2):238-250.[in Chinese])(  2) 2)

|

| [3] |

兰国玉, 胡跃华, 曹敏, 等. 2008. 西双版纳热带森林动态监测样地——树种组成与空间分布格局. 植物生态学报, 32(2):287-298. (Lan G Y, Hu Y H, Cao M, et al. 2008. Establishment of Xishuangbanna tropical forest dynamics plot:species compositions and spatial distribution patterns. Journal of Plant Ecology, 32(2):287-298.[in Chinese])(  2) 2)

|

| [4] |

林露湘, 曹敏, 唐勇, 等. 2002. 西双版纳刀耕火种弃耕地树种多样性比较研究. 植物生态学报, 26(2):216-222. (Lin L X, Cao M, Tang Y, et al. 2002. Tree species diversity in abandoned swidden fields of Xishuangbanna, SW China. Acta Phytoecologica Sinica, 26(2):216-222.(in Chinese)](  1) 1)

|

| [5] |

马姜明, 刘世荣, 史作民, 等. 2007. 川西亚高山暗针叶林恢复过程中群落物种组成和多样性的变化. 林业科学, 43(5):17-23. (Ma J M, Liu S R, Shi Z M, et al. 2007. Changes of species composition and diversity in the restoration process of sub-alpine dark brown coniferous forests in western Sichuan, China. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 43(5):17-23.[in Chinese])(  1) 1)

|

| [6] |

茹文明, 张金屯, 张峰, 等. 2006. 历山森林群落物种多样性与群落结构研究. 应用生态学报, 17(4):561-566. (Ru W M, Zhang J T, Zhang F, et al. 2006. Species diversity and community structure of forest communities in Lishanmountain. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 17(4):561-566.[in Chinese])(  1) 1)

|

| [7] |

苏建荣, 刘万德, 张志钧, 等. 2012. 云南中南部季风常绿阔叶林恢复生态系统萌生特征. 生态学报, 32(3):805-814. (Su J R, Liu W D, Zhang Z J, et al. 2012. Sprouting characteristic in restoration ecosystems of monsoon evergreen broad-leaved forest in south-central of Yunnan Province. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 32(3):805-814.[in Chinese])(  2) 2)

|

| [8] |

吴征镒. 1980. 中国植被.北京:科学出版社. (Wu Z Y.1980. China vegetation. Beijing:Science Press.[in Chinese])(  1) 1)

|

| [9] |

阎恩荣, 王希华, 施家月, 等. 2005. 木本植物萌枝生态学研究进展. 应用生态学报, 16(12):2459-2464. (Yan E R, Wang X H, Shi J Y, et al. 2005. Sprouting ecology of woody plants:a research review. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 16(12):2459-2464.[in Chinese])(  1) 1)

|

| [10] |

阎海平, 谭笑, 孙向阳, 等. 2001. 北京西山人工林群落物种多样性的研究. 北京林业大学学报, 23(2):16-19. (Yan H P, Tan X, Sun X Y, et al. 2001. Studies on species diversity of plantation community on Beijing Xishan.Journal of Beijing Forestry University, 23(2):16-19.[in Chinese])(  1) 1)

|

| [11] |

叶万辉, 曹洪麟, 黄忠良, 等. 2008. 鼎湖山南亚热带常绿阔叶林20公顷样地群落特征研究. 植物生态学报, 32(2):274-286. (Ye W H, Cao H L, Huang Z L, et al. 2008.Community structure of a 20 hm2 lover subtropical evergreen broadleaved forest plot in Dinghushan, China. Journal of Plant Ecology, 32(2):287-298.[in Chinese])(  2) 2)

|

| [12] |

祝燕, 赵谷风, 张俪文, 等. 2008. 古田山中亚热带常绿阔叶林动态监测样地-群落组成与结构. 植物生态学报, 32(2):262-273. (Zhu Y, Zhao G F, Zhang L W, et al. 2008. Community composition and structure of Gutianshan forest dynamic plot in a mid-subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forest, east China. Journal of Plant Ecology, 32(2):287-298.[in Chinese])(  1) 1)

|

| [13] |

Anderson-Teixeira K J, Davies S J, Bennett A C, et al. 2015. CTFS-ForestGEO:a worldwide network monitoring forests in an era of global change. Global Change Biology, 21(2):528-549.( 1) 1)

|

| [14] |

Ashton L A, Barlow H S, Nakamura A, et al. 2015. Diversity in tropical ecosystems:the species richness and turnover of moths in Malaysian rainforests. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 8(2):132-142.( 1) 1)

|

| [15] |

Bachman S, Baker W J, Brummitt N, et al. 2004. Elevational gradients, area and tropical island diversity:an example from the palms of New Guinea. Ecography, 27(3):299-310.( 1) 1)

|

| [16] |

Bellingham P J, Sparrow A D. 2000.Resprouting as a life history strategy in woody plant communities.Oikos, 89(2):409-416.( 1) 1)

|

| [17] |

Bond W J, Midgley J J. 2001. Ecology of sprouting in woody plants:the persistence niche. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 16(1):45-51.( 2) 2)

|

| [18] |

Bond W J, Midgley J J. 2003a. The evolutionary ecology of sprouting. International Journal of Plant Science, 164(s):103-114.( 1) 1)

|

| [19] |

Bond W J, Midgley G F, Woodward F I. 2003b. The importance of low atmospheric CO2 and fire in promoting the spread of grasslands and savannas. Global Change Biology, 9(7):973-982.( 1) 1)

|

| [20] |

Bradley K L, Pregitzer K S. 2007. Ecosystem assembly and terrestrial carbon balance under elevated CO2. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 22(10):538-547.( 1) 1)

|

| [21] |

Brehm G, Colwell R K, Kluge J. 2007. The role of environment and mid-domain effect on moth species richness along a tropical elevational gradient. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16(2):205-219.( 1) 1)

|

| [22] |

Bunyavejchewin S, Baker P J, LaFrankie J V, et al. 2001. Stand structure of a seasonal dry evergreen forest at HuaiKhaKhaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Western Thailand. Natural History Bulletin of the Siam Society, 49(2):89-106.( 1) 1)

|

| [23] |

Calvo L, Tárrega R, de Luis E. 2002. Secondary succession after perturbations in a shrubland community. Acta Oecologica, 23(6):393-404.( 1) 1)

|

| [24] |

Condit R. 1995. Research in large, long-term tropical forest plots. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 10(1):18-22.( 1) 1)

|

| [25] |

Condit R, Ashton P S, Balslev H, et al. 2005. Tropical tree α-diversity:results from a worldwide network of large plots. Biologiske Skrifter, 55(3):565-582.( 3) 3)

|

| [26] |

Condit R, Ashton P S, Bunyavejchewin S, et al. 2006. The importance of demographic niches to tree diversity. Science, 313(5783):98-101.( 1) 1)

|

| [27] |

Condit R, Ashton P S, Manokaran N, et al. 1999. Dynamics of the forest communities at Pasoh and Barro Colorado:comparing two 50-ha plots. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B, 354(1391):1739-1748( 1) 1)

|

| [28] |

Condit R, Hubbell S P, Foster R B. 1996. Changes in tree species abundance in a neotropical forest:impact of climate change. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 12(1):231-256.( 1) 1)

|

| [29] |

Condit R, Pitman N, Leigh Jr. E G, et al. 2002. Beta-diversity in tropical forest trees. Science, 295(5555):666-669.( 1) 1)

|

| [30] |

Fraser L H, Jentsch A, Sternberg M. 2014. What drives plant species diversity? A global distributed test of the unimodal relationship between herbaceous species richness and plant biomass. Journal of Vegetation Science, 25(5):1160-1166.( 1) 1)

|

| [31] |

Gotmark F, von Proschwitz T, Franc N. 2008. Are small sedentary species affected by habitat fragmentation? Local vs. landscape factors predicting species richness and composition of land molluscs in Swedish conservation forests. Journal of Biogeography, 35(6):1062-1076.( 1) 1)

|

| [32] |

Grant C D, Loneragan W A. 1999. The effects of burning on the understorey composition of 11-13 year-old rehabilitated bauxite mines in Western Australia. Plant Ecology, 145(2):291-305.( 1) 1)

|

| [33] |

Grime J P. 1997. Biodiversity and ecosystem function:the debate deepens. Science, 277(5330):1260-1261.( 1) 1)

|

| [34] |

Grman E, Brudvig L A. 2014. Beta diversity among prairie restorations increases with species pool size, but not through enhanced species sorting. Journal of Ecology, 102(4):1017-1024.( 1) 1)

|

| [35] |

Hooper E R, Legendre P, Condit R. 2004. Factors affecting community composition of forest regeneration in deforested, abandoned land in Panama. Ecology, 85(12):3313-3326.( 1) 1)

|

| [36] |

Hubbell S P. 2006. Netural theory and the evolution of ecological equivalence. Ecology, 87(6):1387-1398.( 1) 1)

|

| [37] |

Hubbell S P, Foster R B. 1986. Biology, chance and history and the structure of tropical rain forest tree communities//Diamond J M,Case T J.Community Ecology. New York:Harper & Row New York, 314-329.( 1) 1)

|

| [38] |

Hudson P. 2014. Remarkable species diversity on adjacent salt lakes in South Australia. Acta Geologica Sinica -English Edition, 88(s1):73-73.( 1) 1)

|

| [39] |

Kruger L M, Midgley J J. 2001. The influence of resprouting forest canopy species on richness in Southern Cape forests, South Africa. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 10(5):567-572.( 2) 2)

|

| [40] |

Kubo M, Sakio H, Shimano K, et al. 2005. Age structure and dynamics of Cercidiphyllum japonicum sprouts based on growth ring analysis. Forest Ecology and Management, 213(1/3):253-260.( 1) 1)

|

| [41] |

Lee H S, Davles S J, LaFrankle J V, et al. 2002. Floristic and structural species-rich genus of neotropical rain forest trees. Science, 293(5538):2242-2245.( 2) 2)

|

| [42] |

Luoga E J, Witkowski E T F, Balkwill K. 2004. Regeneration by coppicing(resprouting) of mimbo(African savanna) trees in relation to land use. Forest Ecology and Management, 189(1/3):23-35.( 2) 2)

|

| [43] |

Miller P M, Kauffman J B. 1998.Seedling and sprout response to slash-and-burn agriculture in tropical deciduous forest. Biotropica, 30(4):538-546.( 1) 1)

|

| [44] |

Moreira B, Tormo J, Pausas J G. 2012. To resprout or not to resprout:factors driving intraspecific variability in resprouting. Oikos, 121(10):1577-1584.( 1) 1)

|

| [45] |

Pausas J G, Carbó E, Caturla R N, et al. 1999. Post-fire regeneration patterns in the eastern Iberian Peninsula. Acta Oecologica, 20(5):499-508.( 1) 1)

|

| [46] |

Pimm S L, Brown J H. 2004. Domains of diversity. Science, 304(5672):831-833.( 1) 1)

|

| [47] |

Rydberg D. 2000. Initial sprouting, growth and mortality of European aspen and birch after selective coppicing in central Sweden. Forest Ecology and Management, 130(1/3):27-35.( 1) 1)

|

| [48] |

Sukumar R, Dattaraja H S, Suresh H S, et al. 1992. Longterm monitoring of vegetation in a tropical deciduous forest in Mudumalai, southern India. Current Science, 62(9):608-616.( 1) 1)

|

| [49] |

Thompson J, Brokaw N, Zimmerman J K, et al. 2002. Land use history, environment, and tree composition in a tropical forest. Ecological Applications, 12(5):1344-1363.( 2) 2)

|

| [50] |

Tilman D, Downing J A. 1994. Biodiversity and stability in grasslands. Nature, 367(6461):363-365.( 1) 1)

|

| [51] |

Valencia R, Foster R B, Villa G, et al. 2004. Tree species distributions and local habitat variation in the Amazon:large forest plot in eastern Ecuador. Journal of Ecology, 92(2):214-229.( 1) 1)

|

| [52] |

Vesk P A. 2006. Plant size and resprouting ability-trading tolerance and avoidance of damage. Journal of Ecology, 94(5):1027-1034.( 1) 1)

|

| [53] |

Vesk P A, Westoby M. 2004. Sprouting ability across diverse disturbances and vegetation types worldwide. Journal of Ecology, 92(2):310-320.( 1) 1)

|

| [54] |

Vieira D L M, Scariot A. 2006. Principles of natural regeneration of tropical dry forests for restoration. Restoration Ecology, 14(1):11-20.( 1) 1)

|

2016, Vol. 52

2016, Vol. 52