文章信息

- 胡晓静, 张文辉, 何景峰

- Hu Xiaojing, Zhang Wenhui, He Jingfeng

- 秦岭南坡栓皮栎实生苗的构型分析

- Architectural Analysis of Quercus variabilis Seedlings in the South Slopes of Qinling Mountains

- 林业科学, 2015, 51(9): 157-164

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2015, 51(9): 157-164.

- DOI: 10.11707/j.1001-7488.20150920

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2014-06-10

- 修回日期:2014-10-12

-

作者相关文章

2. 石河子大学农学院 石河子 832000

2. Agriculture College, Shihezi University Shihezi 832000

植物在长期的生长发育过程中,由于遗传结构的不同以及生境条件的差异,它们长期适应不同的生态环境条件,会产生趋同或趋异适应的特征(臧润国等,1998),特别是外部形态特征上。这种外部形态的适应是植物内在遗传信息在一定时间的表现,是其内部生长对策的表达形式,可用构型来表示(卢康宁等,2010)。对于树木来说,构型是指树木的形体建筑结构及动态特点,包括树形、冠形、分枝结构以及树体组成部分(芽、枝、叶等)的空间排布格局,内在生物量构造组成及其配比结构和树体组成单位(组件)及组成部分的数量变化动态等(Hallé et al.,1978;张丹,2011)。由于植物的固着生长,在整个生活史的不同发育阶段,其自身的生理生长及外部环境都处于不断变化之中,表现出一定程度的形态可塑性,其构型特征存在着差异(Sprugel et al.,1991;孙书存等,1999a)。即使在同一生长阶段,由于环境、资源的异质性,同一物种间的构型也不同(Borchert et al.,1981;孙书存等,1999b)。过去对植物表型可塑性的研究多集中在叶片如何适应变化的环境,而忽视了植物整体可塑性方面的研究(如植株生长和生物量分配的可塑性)(Valladares et al.,2000),而正是这种整体的可塑性决定了植物能否在不同环境中存活和生长。

栓皮栎(Quercus variabilis)为壳斗科(Fagaceae)栎属落叶乔木,是重要的用材、软木、栲胶和能源树种。其速生、耐旱、耐瘠薄,是我国暖温带落叶阔叶林和亚热带常绿落叶阔叶混交林的重要建群种(郑万均,1985),广泛存在于秦岭南坡的多种林分中。以往对栓皮栎的研究主要集中在种群生殖动态、种群年龄结构和生物学生态学特性等方面(吴明作等,2001;韩照祥等,2005;张文辉等,2002),有关栓皮栎实生苗构型分析的研究还未见报道。本研究以栓皮栎实生苗为研究对象,比较阴、阳坡不同生境中植株生长、枝系构型、生物量及其分配的变化,研究在幼年时期其形态建成过程中的适应策略是否不同,探讨构型与生境的关系,为森林结构及其经营措施优化提供依据。

1 研究地区与研究方法 1.1 研究区自然概况研究区位于秦岭南坡的陕西省山阳县(33°09′—33°42′ N,109°32′—110°29′ E),属北亚热带向暖温带过渡的季风性半湿润山地气候,年平均气温13.1 ℃,年平均无霜期为207天,年平均日照2 133.8 h,日照率48%,年平均降水量709.3 mm。栓皮栎是当地主要森林类型,主要分布在海拔800~1 500 m,乔木层郁闭度0.7~0.8,伴生树种主要有麻栎(Quercus acutissima)、槲栎(Quercus aliena)等,高度为7~12 m;林下灌木盖度为0.2~0.4,高度为0.5~1.5 m,主要有胡枝子(Lespedeza bicolor)、黄栌(Cotinus coggygria)、杜梨(Pyrus betulifolia )等;草本层盖度为0.2~0.4,高为10~40 cm,以百合科(Liliaceae)的麦冬(Ophiopogon japonicus)和莎草科(Cyperaceae)的苔草属(Carex)植物为主。

研究区的林分近年来没有进行过较大规模采伐或破坏活动,林相发育良好。研究样地设在栓皮栎成熟林,具体环境因子见表 1。其海拔、坡度和坡位相差不多,但由坡向不同而导致的不同水热条件可能对实生苗的生长造成影响,因此依据坡向将生境划分为阳坡和阴坡。其中阳坡样地面积60 m×20 m,阴坡样地面积60 m×15 m,各分成3个样方。幼苗在各个样地中林冠下进行选取,其中阳坡林冠下湿度平均38.4%,光照强度1.57×104 lx,土壤含水量254.5 L ·m-3;阴坡林冠下湿度平均68.7%,光照强度0.63×104 lx,土壤含水量316.2 L ·m-3。

|

|

1)构型参数观测 为更好地区分栓皮栎幼苗在不同生境中的构型变化,采用典型抽样法(Abrams,1986;徐程扬,2001),每个样方中分别选取生长发育正常的1~10年生的林冠下幼苗各3~5 株,阳坡共计125 株,阴坡共计113 株。于全叶期,测定每个植株的高、地径、冠幅、枝长、各级分枝枝径等参数,计算枝径比(RBD)(RBD=Di+1/Di,式中: Di+1和Di分别是第i+1级和i级枝条的直径),用半圆仪测量分枝角,测定各侧枝在树干上的位置(距主干顶芽的距离),并统计各级枝条上的现存叶数。

2)枝序的确定与分枝率计算 按照植株分枝发育顺序的离心法确定枝序(Borchert et al.,1981;杨小艳等,2010),即把直接着生于主干上的枝定为一级枝,着生于一级枝上的侧枝为二级枝,着生于二级枝上的侧枝为三级枝,依此类推,并分别计算总体分枝率(Rb)和逐步分枝率(Ri:i+1)(Steingraeber et al.,1986;孙书存等,1999a)。Rb=(Nt-Ns)/(Nt-N1),式中: Nt为所有枝级中枝条的总数,Ns为最高枝级的枝条数,N1为第一级的枝条总数。某一级枝条数与下一个高枝级的枝条数之比为逐步分枝率(Ri:i+1)。Ri :i+1=Ni/Ni+1,式中: Ni为第i级的枝条总数,Ni+1为第i+1级的枝条总数。

3)实生苗年龄的确定 1~4年实生苗个体年龄通过主茎上的芽鳞痕、茎干颜色确定,4年以上(不包括4年)实生苗个体的年龄通过观察主茎上的芽鳞痕,同时用放大镜观察基部年轮数确定(张文辉等,2002)。

4)叶面积指数计算 叶片带回实验室后,先用EPSON PERFECTION 4870 扫描仪将叶片扫描成图片文件,用WinFOLIA 2004a 软件分析叶面积(leaf area,LA)(Hölscher et al.,2002;祁建等,2008)。依据公式计算单株的叶面积指数:LAI=LA×N/(π× R2)。式中: LAI 为叶面积指数;LA为平均单叶面积;N为单株实生苗总叶片数;R为实生苗冠幅的半径。

5)生物量测定 每株幼苗采用全挖法将根系挖出,将其茎、叶、侧枝、根分别取样并称取鲜质量,带回实验室在80 ℃下烘干至恒质量,称量,测得各构件含水率,根据含水率计算各构件的生物量和总生物量,计算根茎比(根系生物量/地上部分生物量)。同时计算干生物量、叶生物量、侧枝生物量与地上生物量的比值,从构件生物量的比率变化说明栓皮栎实生苗构型的变化。

6)数据处理 采用EXCEL和SPSS16.0进行数据处理及运算;ORIGIN7.5进行图形处理。

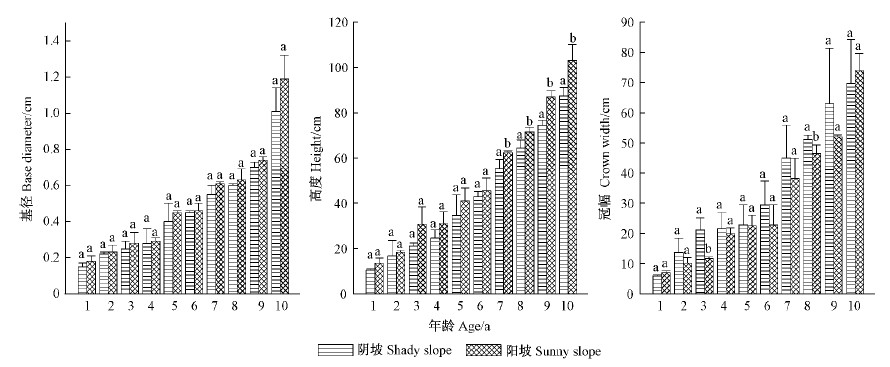

2 结果与分析 2.1 生长特性不同立地条件下的林分,在接受太阳辐射、吸收降水量等方面有差异,形成了各自不同的林内小环境(Jackson et al.,1996),从而使得林内的实生苗木生长也有不同。阳坡和阴坡2个生境中栓皮栎实生苗,随着苗木年龄的增长,其基径、高度、冠幅均有一定程度的增长(图 1),且各个年龄实生苗的基径、树高均是阳坡>阴坡,但基径在2个生境间没有显著差异,树高在7年后出现显著差异;冠幅9年生之前各年龄均是阴坡>阳坡,在3年生和8年生时差异显著,其他各个年龄在2个生境间无显著差异。从上述苗木特征可以看出,阳坡的栓皮栎林内较阴坡更有利于实生苗的生长。

|

图 1 不同生境中栓皮栎实生苗的基径、高度和冠幅特征 Fig.1 Base diameter, height and crown width traits of Q. variabilis seedlings in different habitats 数据为平均值±标准误。不同字母代表数据在生境间差异显著(P<0.05)。下同。Bars are mean value ± standard error. Different letters indicate significant difference among habitats. The same below. |

1)枝系特征 分枝率是对树冠分枝强度的一种度量,可表示枝条的分枝能力以及各枝级间的数量配置状况(Borchert et al.,1981;黎云祥等,1998)。表 2的统计结果表明,在阴坡,栓皮栎幼苗4年生时出现1级枝,阳坡则出现在5年生时;3级枝的出现也是阴坡早于阳坡,阴坡出现在6年生,而阳坡则出现在8年生。总体分枝率与逐步分枝率(R1 :2)在2个生境中有差异,表现为阳坡>阴坡,但在各年龄间的这种差异并不总是显著。幼苗枝径比在2个生境中的差异不显著(P>0.05)。分枝角体现了树木向空间扩展的能力,并直接影响着树木对光照、温度等资源的利用(Cluzeau et al.,1994)。各年龄幼苗的1级枝分枝角和1级枝长度在2个生境间差异并不显著(除4年生苗),但都表现为阴坡>阳坡,尤其在5年生时1级枝分枝角的平均值相差29.3°。生活在阴坡林冠下的栓皮栎幼苗,植株下部枝条接受的光照较弱,枝条渐趋平展,从而使所附着的叶能更好地接受林内的散射光。

|

|

2)叶片形态特征 叶片形状和大小也是植冠形态的重要特征,它影响叶片之间相互的遮荫和树冠对光的吸收(Falster et al.,2003),并进一步影响到枝系的生长和生存。各个年龄栓皮栎幼苗的叶长、叶宽和单叶面积在阴坡和阳坡2个生境间均无显著差异(P>0.05),但均表现为阴坡>阳坡;叶面积指数也表现为阴坡>阳坡,但除3年生外其他年龄段幼苗在2个生境间也无显著差异(表 3),叶面积指数是一个综合参数,是植物体本身属性同外部光照、水热条件相互作用后的表征(孙书存等,1999a)。阴坡林内幼苗通过加大叶面积和叶片数量来增加对于光照的吸收。幼苗的叶长宽比在各个年龄段以及阴坡、阳坡2个生境未有明显差异(P>0.05),基本变化在2.00~2.61,这可能是因为叶长宽比由遗传性状所控制,是遗传型对表现型的控制方式,不容易随环境的不同而产生变异(林勇明等,2009)。

|

|

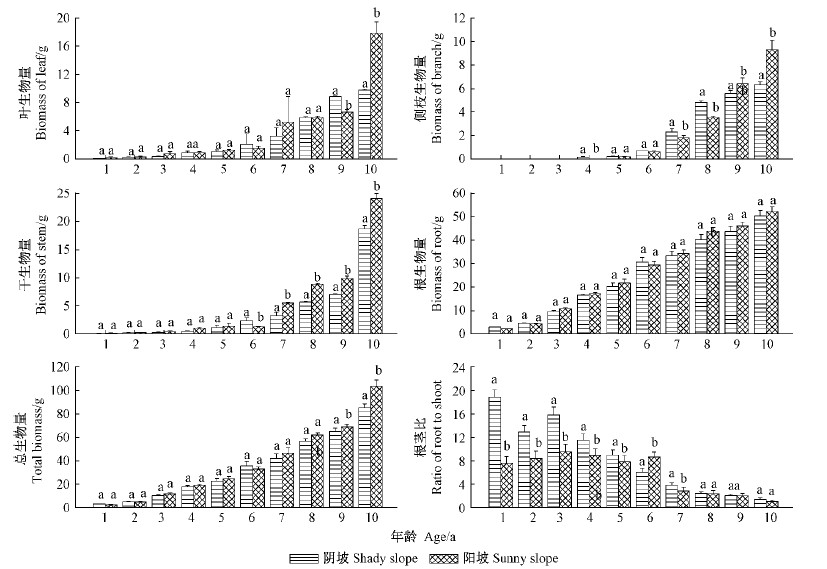

植物生物量的增长是植物自身与环境因素共同作用的结果,它既反映了植物对环境条件的适应及利用状态,也反映了环境条件对植物的影响和饰变程度(张文辉等,2003)。由图 2可知,2个生境中栓皮栎实生苗的叶、干、侧枝的生物量均呈指数形式增长,1~5年生苗生物量增长缓慢,6年后增长加快。2个生境间各年龄实生苗的叶、干、侧枝生物量均表现为在1~5年间无显著差异,随着年龄增长,2个生境间的差异越来越显著(P<0.05),根生物量则没有太大差异。根茎比反映了幼苗对于资源的分配比例,在1~7年生时在阳坡和阴坡间有显著差异(P<0.05),且阴坡根茎比的数值大于阳坡,这意味着在8年生之前扩展根系对栓皮栎幼苗非常重要,其生物量格局是把较多的干物质分配到地下部分,尤其是在光照不足的阴坡林内,确保幼苗的存活。

|

图 2 不同生境中栓皮栎实生苗的构件生物量 Fig.2 Modular biomass of Q. variabilis seedlings in different habitats |

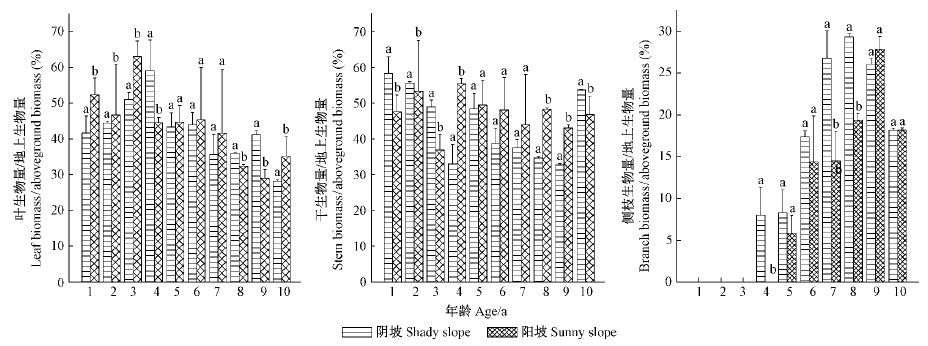

随着个体生物量的积累,各器官生物量占地上生物量的比率也随之发生变化,而且高峰出现的年龄也不同(图 3)。在阴坡,叶生物量比率在第4年时最高,侧枝生物量比率在8年时最高;而阳坡,叶生物量比率最高出现在第3年时,侧枝生物量比率最高则出现在第9年时。2个生境中,干、叶生物量比率在1~4年时有显著差异,但随着年龄增大,差异明显变小,但在8年生后,又有显著差异。各生物量的差异及其比率高峰出现的年龄差异主要是由于生境条件的差异所致。为了充分利用各生境内的资源,植物通过调整各器官的生长发育、生物量分配等以适应环境条件,形成对不同生境的适应策略。

|

图 3 不同生境中栓皮栎实生苗的构件生物量/地上生物量的比率 Fig.3 The ratio of modular biomass to aboveground biomass of Q. variabilis seedlings in different habitats |

植物构型特征(如器官的数量和几何形状)是遗传特性,然而在它们发生和发育过程中又高度依赖环境条件(Godin,2000),对于外界环境的变化,植物能以形态可塑性来适应环境变化(Valladares et al.,2007)。由于植物固着生长,个体适应环境变化的方式主要是构型随环境发生改变(Valladares et al.,2007)。植物构型改变直接影响植株对环境中光热资源的利用,特别有利于植物在不良环境下最大限度地利用环境(Lee et al.,1991)。光照一直被认为是决定植株形态的限制因素,木本植物地上部分的形态差异可能主要是对光照条件的潜在适应能力所致(Küppers,1989;Sprugel et al.,1991)。本研究结果也认为在不同坡向的林分内,由于光热资源的竞争而导致栓皮栎幼苗在分枝构型方面产生了一定的差异性。在阴坡林内,光照条件受限制,为了拓展生存空间,栓皮栎幼苗枝系生长以拓展横向空间为主,1级枝长、分枝角度大、分枝能力也较阳坡高,幼苗通过侧枝的水平生长增大冠幅来获取更多的光辐射和营养空间,而且通过强烈分枝来提高光利用率,同时幼苗的叶长、叶宽、单叶面积也较阳坡大。可见为了充分利用不同生境内的光资源,栓皮栎幼苗形成了不同的适应策略。

在植物个体发育过程中,由于各器官功能的不同,植物需要把资源进行分配,去维持各器官在个体生长发育和繁殖过程中的生理机能,使得植物个体在不同发育阶段具有不同的资源分配对策(Sharma et al.,1999;梁艳等,2008)。通过有效调节自身生物量配置,植物把有限的资源通过自身的生理整合有规律地分配到各器官中去,优化各器官的功能实现自身适合度的最大化(Brock,1983;何亚平等,2008),来适应不同生境。不同环境条件下,植物不同表型结构对环境选择作出反应,在植物生长与繁殖、种群生存与维持等功能方面,实现种群个体各器官生物量投资的优化配置来适应多样化的环境(Bazzaz et al.,1987;姚红等,2005)。光强变化导致生物量分配模式的改变可能是幼苗在异质光环境下生存的重要原因(陈圣宾等,2005)。本研究中2个生境中栓皮栎幼苗的生物量分配存在一定程度的差异。随着年龄增长,2个生境间的各器官生物量差异越来越显著(P<0.05),且各器官生物量比率出现高峰的年龄也不同。根茎比在1~7年生时有显著差异(P<0.05),且阴坡的根茎比数值大于阳坡。一般认为,植物的形态可塑性与植物在遮荫环境下的生存和生长有关(Valladares et al.,2002)。在光照不充足的阴坡林内,作为喜光植物的栓皮栎(张文辉等,2002),其幼苗可通过增加叶和侧枝生物量比率,来吸收足够的光能,同时将更多的干物质集中分配到根部,从而在高遮光条件下确保苗木的存活和相对正常的生长。这些构型特征的变化进一步说明了栓皮栎幼苗在生长过程中对环境的适应能力,以及这些构型特征与生境之间的关系。

| [1] |

陈圣宾, 宋爱琴, 李振基. 2005. 森林幼苗更新对光环境异质性的响应研究进展. 应用生态学报, 16(2): 365-370. (Chen S B, Song A Q, Li Z J. 2005. Research advance in response of forest seedling regeneration to light environmental heterogeneity. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 16(2): 362-370[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [2] |

韩照祥, 山仑. 2005. 栓皮栎种群变异与适应对策研究. 林业科学, 412(6): 16-22. (Han Z X, Shan L. 2005. Variation and adaptive countermeasures of Quercus variabilis population in Shaanxi Province. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 412(6): 16-22[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [3] |

何亚平, 段元文, 费世民, 等. 2008. 青藏高原天山报春高寒湿地种群的花期资源分配. 应用与环境生物学报, 14(2): 180-186. (He Y P, Duan Y W, Fei S M, et al. 2008. Resource allocation of Primula nutans population in the alpine wetland of the east Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China.Chin J Appl Environ Biol, 14(2): 180-186[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [4] |

黎云祥, 陈利, 杜道林, 等. 1998. 四川大头茶的分枝率和顶芽动态. 生态学报, 18(3): 309-314. (Li Y X, Chen L, Du D L, et al. 1998. The bifurcation ratios and leader-bud dynamics of Gordonia acuminata. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 18(3): 309-314[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [5] |

梁艳, 张小翠, 陈学林. 2008. 多年生龙胆属植物个体大小与花期资源分配研究. 西北植物学报, 28(12): 2400-2407. (Liang Y, Zhang X C, Chen X L. 2008. Individual size and resource allocation in perennial Gentiana. Acta Botanica Boreali-Occidentalia Sinica, 22(5): 1093-1101[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [6] |

林勇明, 洪滔, 吴承祯, 等. 2009. 不同起源与方位下桂花的构型差异. 福建林学院学报, 29(2): 97-102. (Lin Y M, Hong T, Wu C Z, et al. 2009. Architectural variation of Osmanthus fragrans in different origins and orientations. Journal of Fujian College of Forestry, 29(2): 97-102[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [7] |

卢康宁, 张怀清. 2010. 植物构筑型研究综述. 世界林业研究, 23(1):17-20. (Lu K N, Zhang H Q. 2010. A review of plant architecture. World Forestry Research, 23(1):17-20[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [8] |

祁建, 马克明, 张育新. 2008. 北京东灵山不同坡位辽东栎(Quercus liaotungensis)叶属性的比较. 生态学报, 28(1): 122-128. (Qi J, Ma K M, Zhang Y X. 2008. Comparisons on leaf traits of Quercus liaotungensis Koidz. on different slope positions in Dongling Mountain of Beijing.Acta Ecologica Sinica, 28(1): 122-128[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [9] |

孙书存, 陈灵芝. 1999a. 不同生境中辽东栎的构型差异. 生态学报, 19(3): 359-364. (Sun S C, Chen L Z. 1999a.The architectural variation of Quercus liaotungensis in different habitats. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 19(3): 359-364[in chinese]).(  3) 3)

|

| [10] |

孙书存, 陈灵芝. 1999b. 辽东栎的构型分析. 植物生态学报, 25(3): 433-440. (Sun S C, Chen L Z. 1999b. Architectural analysis of crown geometry in Quercus liaotungensis. Acta Phytoecologica Sinica, 23(5): 433-440[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [11] |

吴明作, 刘玉萃, 姜志林. 2001. 栓皮栎种群生殖生态与稳定性机制研究. 生态学报, 21(2): 225-230. (Wu M Z, Liu Y C, Jiang Z L. 2001. The reproductive ecology and stable mechanism of Quercus variabilis ( Fagaceae) population. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 21(2): 225-230[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [12] |

徐程扬. 2001. 不同光环境下紫椴幼树树冠结构的可塑性响应. 应用生态学报, 12(3): 339-343. (Xu C Y. 2001. Response of structural plasticity of Tilia amurensis sapling crowns to different light conditions. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 12(3): 339-343[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [13] |

杨小艳, 尹林克, 姜逢清, 等. 2010. 不同配置城市防护绿地中胡杨构型特征. 干旱区资源与环境, 24(6): 178-183. (Yang X Y, Yin L K, Jiang F Q, et al. 2010. Response of branching architectures characteristics of Populus euphratica in different collocation in shelterbelts. Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment, 24(6): 178-183[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [14] |

姚红, 谭敦炎. 2005. 胡卢巴属4种短命植物个体大小依赖的繁殖输出与生活史对策. 植物生态学报, 29(6): 954-960. (Yao H, Tan D Y. 2005. Size-dependent reproductive output and life-history strategies in four ephemeral species of Trigonella. Acta Phytoecologica Sinica, 29(6): 954-960[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [15] |

臧润国, 蒋有绪. 1998. 热带树木构筑学研究概述. 林业科学, 34(5):112-119. (Zang R G, Jiang Y X. 1998. Review on the architecture of tropical trees. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 34(5):112-119[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [16] |

张丹. 2011. 沙质海岸防护林黑松根系构筑型研究. 泰安:山东农业大学博士学位论文. (Zhang D. 2011. Root architecture of Pinus thunbergii in sandy coast protective forest. Tai'an: PhD Thesis of Shandong Agricultural University[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [17] |

张文辉, 李红, 李景侠, 等. 2003. 秦岭独叶草种群个体和构件生物量动态研究. 应用生态学报, 14(4): 530-534. (Zhang W H, Li H, Li J X, et al. 2003. Individual and modular biomass dynamics of Kingdonia uninflora population in Qinling Mountain. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 14(4): 530-534[in chinese]).(  1) 1)

|

| [18] |

张文辉, 卢志军. 2002. 栓皮栎种群的生物学生态学特性和地理分布研究. 西北植物学报, 22(5): 1093-1101. (Zhang W H, Lu Z J. 2002. A study on the biological and ecological property and geographical distribution of Quercus variabilis population. Acta Botanica Boreali-Occidentalia Sinica, 22(5): 1093-1101[in chinese]).(  3) 3)

|

| [19] |

郑万均. 1985. 中国树木志. 北京: 中国林业出版社. (Zheng W J. Chinese Sylvae. 1985. Beijing: China Forestry Publishing House.[in chinese])(  1) 1)

|

| [20] |

Abrams M D. 1986. Physiological plasticity in water relations and leaf structure of understory versus open-grown Cercis canadensis in north-eastern Kansas. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 16(6):1170-1174.( 1) 1)

|

| [21] |

Bazzaz F A, Chiariello N R, Coley P D, et al. 1987. Allocation resources to reproduction and defense. Bioscience, 37(1):58-67.( 1) 1)

|

| [22] |

Borchert R, Slade N A. 1981. Bifurcation ratios and the adaptive geometry of trees. Bot Gaz, 142(3): 394-401.( 3) 3)

|

| [23] |

Brock M A. 1983. Reproduction allocation in annual and perennial species of the submerged aquatic halophyte Ruppia. Journal of Ecology, 71(3):811-819.( 1) 1)

|

| [24] |

Cluzeau C N, Goff L, Ottorini J M. 1994. Development of primar branches and crown profile of Fraxinus excelsior. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 24(12): 2315-2323.( 1) 1)

|

| [25] |

Falster D S, Westoby M. 2003. Leaf size and angle vary widely across species: what consequences for light absorption? New Phytologist, 158(3): 509-525.( 1) 1)

|

| [26] |

Godin C. 2000. Representing and encoding plant architecture: a review. Annals of Forest Science, 57(5): 413-438.( 1) 1)

|

| [27] |

Hallé F, Oldeman R A A, Tomlinson P B. 1978. Tropical trees and forests: an architectural analysis. Berlin:Springer-Verlag.( 1) 1)

|

| [28] |

Hölscher D, Hertel D, Leuschner C, et al. 2002. Tree species diversity and soil patchiness in a temperate broad-leaved forest with limited rooting space. Flora- Morphology Distribution Functional Ecology of Plants, 197(2): 118-125.( 1) 1)

|

| [29] |

Jackson R B, Canadell J, Ehleringer J R, et al. 1996. A global analysis of root distribution for terrestrial biomes. Oecologia, 180(3): 389-411.( 1) 1)

|

| [30] |

Küppers M. 1989. Ecological significance of above ground architectural patterns in woody plants: a question of cost-benefit relationship. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 4(12): 375-379.( 1) 1)

|

| [31] |

Lee D W, Richards J H. 1991. Heteroblastic development in vines//Putz F E, Mooney H A. On the economy of plant form and function. London: Cambridge University Press, 205-243.( 1) 1)

|

| [32] |

Sharma N, Koul A K, Kaul V. 1999. Pattern of resource allocation of six Plantago species with different breeding systems. Journal of Plant Research, 112(1):1-5.( 1) 1)

|

| [33] |

Sprugel D G, Hinckley T M, Schaap W. 1991. The theory and practice of branch autonomy. Annual Review of Ecology Systematics, 22:309-334.( 2) 2)

|

| [34] |

Steingraeber D A, Waller D M. 1986. Non-stationary of tree branching pattern and bifurcation ratios. Proceedings of Royal Society of London B, 228(1251): 187-194.( 1) 1)

|

| [35] |

Valladares F, Chico J, Aranda I, et al. 2002. The greater seedling highlight tolerance of Quercus robur over Fagus sylvatica is linked to a greater physiological plasticity. Trees, 16(6):395- 403.( 1) 1)

|

| [36] |

Valladares F, Gianoli E, Gomez J M. 2007. Ecological limits to plant phenotypic plasticity. New Phytologist, 176(4): 749-763.( 1) 1)

|

| [37] |

Valladares F, WrightS J, Lasso E, et al. 2000. Plastic phenotypic response to light of 16 congeneric shrubs from a Panamanian rainforest. Ecology, 81(7): 1925-1936.( 1) 1)

|

2015, Vol. 51

2015, Vol. 51