文章信息

- 张春雨, 魏彦波, 王德胜, 夏富才, 赵亚洲, 赵秀海

- Zhang Chunyu, Wei Yanbo, Wang Desheng, Xia Fucai, Zhao Yazhou, Zhao Xiuhai

- 水曲柳种群性比及空间分布

- Analysis of Sex Ratios and Spatial Distribution of Dioecious Fraxinus mandshurica

- 林业科学, 2010, 46(10): 167-172.

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2010, 46(10): 167-172.

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2009-05-29

- 修回日期:2010-07-25

-

作者相关文章

2. 吉林省天然林保护工程管理中心 吉林 130000

2. Management Center of Natural Forest Protection Project, Jilin Province Jilin 130000

雌雄异株植物的雌雄植株在营养和繁殖结构的大小、颜色及寿命,资源获得与分配,与群落其他物种相互作用等方面均存在差异(Delph et al., 1996; 2002; Pickering,2000; Gehring et al., 1994)。种群性比是雌雄异株植物的一个重要结构指标,尽管雌树多于雄树(Opler et al., 1978; Alliende et al., 1989),以及性比不显著偏离1:1(Morellato,2004)的种群结构已经被发现,但大量研究显示雄树通常多于雌树(Pickering,2000; Gauquelin et al., 2002; Pickering et al., 2002)。植物空间格局研究主要集中在雌雄同体或雌雄同株的植物,所有植株都可以产生种子。然而对于雌雄异株植物而言,假定种群雌雄植株数相同,那么仅有一半的父母代植物有助于种子的传播。与雌雄同体或雌雄同株的植物相比,雌雄异株植物种源数目的下降将会导致后代局部密度形成很大的空间异质性。尽管这种密度空间异质性对种群动态影响较大(Peterson et al., 1995),但雌雄异株特性对种群空间结构有何影响以及如何影响的仍不清楚。

雌雄植株性比格局、性别内以及性别间相互作用影响着森林结构和树种共存(Zhang et al., 2009)。有雌雄异株树种参与的森林群落树种共存机制研究还处于理论探索阶段。研究成果以推理性或描述性为主,缺乏进一步数据支持和理论验证。水曲柳(Fraxinus mandshurica)是中国东北重要用材树种,为雌雄异株植物。由雌雄异株特性导致的水曲柳雌雄植株生态学特征差异方面的研究刚刚起步。日本学者研究了水曲柳变种(Fraxinus mandshurica var. japonica)与性别相关的种群特征(Takahashi et al., 2001; Goto et al., 2005; 2006)。目前为止,水曲柳种群性比及其与性别相关的空间分布研究还未见报道。本文对长白山次生杨桦林中水曲柳种群结构、性别比例及其与性别相关的空间分布进行了初步研究。

1 材料与方法 1.1 研究区域概况研究样区位于吉林省白河林业局光明林场次生林区,海拔899 m,42°19.168′N,128°07.819′E。属于受季风影响的温带大陆性山地气候,年平均气温为3.3℃,最热月8月平均温度为20.5℃,最冷月1月平均温度为-16.5℃,极端最高温度可达32.3℃,极端最低气温达-37.6℃。年平均降水量在600~900 mm。土壤为山地暗棕色森林土,土层厚度20~100 cm。该区原始植被为阔叶红松林,采伐后形成次生杨桦林,林龄在50~70年。次生杨桦林中DBH > 1 cm木本植物株数密度为4 028株·hm-2,胸高断面积之和为24.74 m2·hm-2。水曲柳胸高断面积占所有树种总胸高断面积的13%。主要乔木种包括红松(Pinus koraiensis)、蒙古栎(Quercus mongolica)、紫椴(Tilia amurensis)、水曲柳、色木槭(Acer mono)、春榆(Ulmus japonica)、糠椴(Tilia mandshurica)、簇毛槭(Acer barbinerve)、假色槭(Acer pseudosieboldianum)、青楷槭(Acer trgmentosum)、白牛槭(Acer mandshurica)、花楷槭(Acer ukurunduense)、怀槐(Maackia amurensis)、三花槭(Acer triflorum)、黄菠萝(Phellodendron amurense)、枫桦(Betula costata)、青杨(Populus ussuriensis)等。张春雨等(2008; 2009)对研究林分的树种组成、大小结构、空间分布状况进行了报道。

1.2 数据收集方法2005年建立5.2 hm2 (260 m × 200 m)固定样地,将其进一步划分为130个20 m × 20 m的连续亚样方。记录样地内所有DBH≥1 cm的乔木个体种名、胸径、树高、冠幅(东西冠幅长、南北冠幅长)、枝下高及其位置坐标。在2006年8月晴天,用手持土壤水分测定仪(HH2 DelLa-T Devices Moisture Meter,U.K.)测量每个亚样方地表 0~5 cm土壤层湿度。水曲柳雌雄植株都在早春开花,翅果长2.5~3. 9 cm,宽0.45~0.6 cm,质量0.027~0.035 g,在7—9月间成熟。种子在研究区主要通过重力传播,通过风的远距离传播较少。于2005—2008年的繁殖季节(4—10月)调查样地内水曲柳性别,利用双筒望远镜观察繁殖器官(花、种子)来判断成熟植株的性别。本文以观察期间的累计性别表达数据为基础,将所有胸径大于5 cm的个体分为:雌树、雄树以及由于观察期间缺少繁殖器官而暂时无法判断性别的植株。本文将胸径小于5 cm的个体定义为幼树。为了分析不同大小阶段的空间分布,将雌雄植株进一步划分为: 5 cm < DBH < 25 cm (小雌树、小雄树)和DBH ≥ 25 cm(大雌树、大雄树)。

1.3 数据分析方法1) 用卡方检验来检验性比(雄/雌)偏离1:1零假设的显著性程度,t检验来确定雌雄植株的胸径大小差异,变异系数(CV =标准偏差/均值)量化胸径大小相对变异(Morellato,2004; Nanami et al., 2005)。统计每个样方内雌雄植株数,剔除雌、雄植株数为0的样方,利用Spearman秩相关系数分析保留的46个样方内性比与土壤水分间的关系。

2) 点格局分析方法-Ripley L函数被用来进行空间格局和空间关系分析,使用

① 单变量空间分布格局 零假设:完全随机假设(complete randomness hypothesis)。使用随机点过程来检验分布偏离完全随机假设的显著性程度,该过程通过10 000次Monte Carlo随机模拟来计算95%的置信区间。当L(t)大于上包迹线时为聚集分布,L(t)在上下包迹线之间时为随机分布,L(t)小于下包迹线时为均匀分布。

② 双变量空间关系 a)零假设:标签随机化假设(random labeling)。保持变量1及变量2全部空间点的位置不变,将变量1随机分配到2个变量的观察位置中,再将变量2随机分配到剩余位置上。重复这个过程10 000次,计算95%置信区间(Diggle,1983)。b)零假设:类型独立假设(types independence)。变量2空间点相对于变量1空间点的10 000次螺旋形转换(toroidal shifts)计算95%置信区间(Diggle,1983)。当L12 (t)大于、等于、小于95%置信区间时分别表示2个变量类型间呈显著正相关(吸引)、空间独立和显著负相关(排斥)。

为了在双变量空间关系分析中正确选择零假设,本文遵循Goreaud等(2003)的原则。将幼树(DBH < 5 cm)和成树(雌树、雄树、未确定性别植株)视为不同的同龄群,它们的特定空间格局是由在时间上事先存在的不同空间过程决定的,因此幼树与成树间的空间关系采用类型独立假设; 而雌树、雄树是在同等先决条件下生长的,后天的空间过程才导致不同性别个体的分布及相互作用出现差异,因此同性或异性间的空间关系则采用标签随机化假设。但为了便于比较,本文性别内及性别间空间关系分析也采用类型独立假设进行验证。

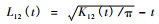

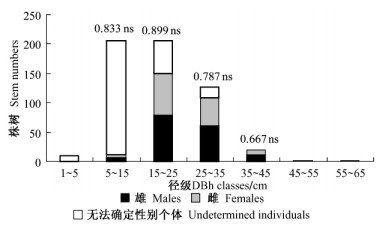

2 结果与分析 2.1 水曲柳大小分布及种群性比全部DBH > 5 cm水曲柳植株在5.2 hm2样地内分布如图 1所示,其中包括135个雄树,158个雌树,以及在观察期间缺乏繁殖器官而暂时无法判断性别植株267个,性别比例(雄/雌)未显著偏离1:1 (卡方检验,P = 0.179)。水曲柳雌树和雄树平均胸径分别为(24.5 ± 6.2) cm和(24.9 ± 7.9) cm。雌树胸径分布范围为5.95~43.59 cm,雄树胸径分布范围为7. 28~58 cm。雌树和雄树胸径在15~35 cm植株分别占全部水曲柳植株的88. 1%和87. 3%。水曲柳雌、雄植株胸径大小差异不显著(t检验,P > 0.1),而大小相对变异系数相同(CVfemale = CVmale = 54%)。随着水曲柳径级增加,无法确定性别的植株逐渐减少,所有DBH > 35 cm植株均表达出特定性别。雄树较雌树出现在更多径级中,并且在全部径级内水曲柳种群性比(雄/雌)均未显著偏离1:1 (卡方检验,P > 0.1) (图 2)。

|

图 1 DBH > 5 cm水曲柳植株在5.2 hm2(260 m × 200 m)样地中空间分布 Figure 1 Distribution of F. mandshurica > 5 cm in DBH in a 5. 2 hm2 plot ○雄树Males ●雌树Females △无法确定性别植株Undetermined individuals |

|

图 2 水曲柳植株大小分布 Figure 2 Size distribution of F. mandshurica trees 条形柱上的数字为性比,ns表示性比不显著偏离1: 1(卡方检验)。 The figures upon bars indicate the sex ratios, ns indicates sex ratio do not significantly deviate from 1: 1 (Chi-square test). |

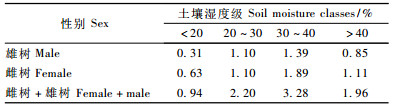

水曲柳雌树和雄树在土壤湿度为30%~40%的样方内出现频数最高(单个样方内雄树和雌树平均株数分别为1.39和1.89),在土壤湿度 < 20%的样方内出现频数最低(单个样方内雄树和雌树平均株数分别为0.31和0.63)(表 1)。水曲柳雌、雄植株数与土壤湿度均呈弱正相关(雌树: r = 0.117,P = 0.184;雄树: r = 0.157,P = 0.074)。性比(雄性/雌性)与土壤湿度呈弱负相关(r =-0.121,P > 0.05)。雌雄异株植物的雌雄植株通常具有不同的环境偏好和资源利用方式,雌树比雄树更加喜好潮湿生境(Ueno et al., 2003)。但水曲柳雌雄植株在土壤水分偏好方面无明显差异。

|

|

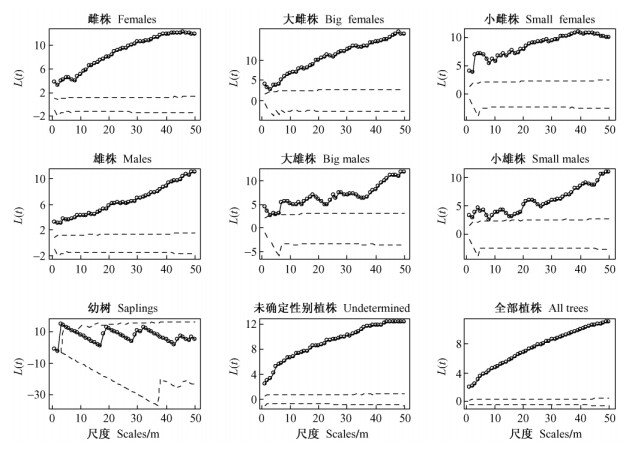

Ripley L(t)单变量空间格局分析表明:在完全随机零假设下,全部DBH > 1 cm的水曲柳植株在样地内呈聚集分布; 水曲柳雌树和雄树在0~50 m尺度上呈聚集分布; 水曲柳小雌树(5 cm < DBH < 25 cm)及大雌树(DBH ≥25 cm)在空间上(0~50 m)呈聚集分布; 水曲柳小雄树(5 cm < DBH < 25 cm)和无法确定性别的水曲柳植株在空间上呈聚集性分布; 水曲柳大雄树(DBH≥25 cm)在0~2,4和7~50 m尺度上呈聚集分布; 水曲柳幼树(1 cm < DBH < 5 cm)在空间上则以随机分布为主(图 3)。

|

图 3 水曲柳空间分布格局 Figure 3 Spatial distribution of F. mandshurica trees Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals under complete randomness hypothesis. 虚线代表完全随机假设下95%置信区间。` |

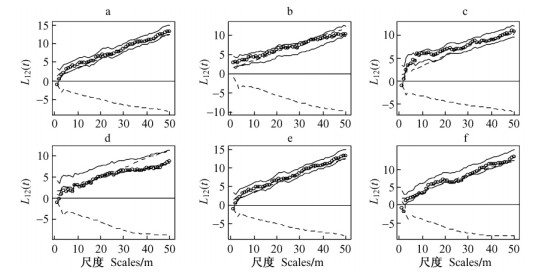

双变量Ripley L12 (t)分析表明:水曲柳幼树(1 cm < DBH < 5 cm)与雌树和雄树在全部研究尺度上均呈空间独立; 水曲柳幼树(1 cm < DBH < 5 cm)与无法确定性别的植株在1~15 m尺度上呈空间正相关; 水曲柳幼树(1 cm < DBH < 5 cm)与全部水曲柳(DBH > 5 cm)在1~14 m尺度上呈空间正相关。雌树与雄树空间关系分析表明:在类型独立零假设下,水曲柳雌树和雄树在3~50 m尺度上相互吸引; 在标签随机化零假设下,水曲柳雌树和雄树在1~5 m和23~28 m空间尺度上相互排斥,在其他尺度上空间独立。不同大小级以及不同性别植株之间相互作用:在类型独立零假设下,不同大小的同性或异性植株之间均呈正相关关系(图 4a-f)。在标签随机化零假设下,水曲柳小雌树(5 cm < DBH < 25 cm)与水曲柳小雄树(5 cm < DBH < 25 cm) (图 4c)、水曲柳小雌树(5 cm < DBH < 25 cm)与水曲柳大雄树(DBH≥ 25 cm) (图 4d)、水曲柳大雌树(DBH≥25 cm)与水曲柳小雄树(5 cm < DBH < 25 cm) (图 4e)、水曲柳大雌树(DBH≥25 cm)与水曲柳大雄树(图 4f)在较窄的不连续的距离尺度上表现为显著负相关。

|

图 4 水曲柳不同大小、不同性别个体之间的空间关系 Figure 4 Spatial relationships among the tree diameter within the same sex and/or the opposite sex, and between the sexes a.小雌树和大雌树; b.小雄树和大雄树; c.小雌树和小雄树; d.小雌树和大雄树; e.大雌树和小雄树; f.大雌树和大雄树.实线代表标签随机化零假设下95%置信区间,虚线代表类型独立零假设下95%置信区间。 a. Small females and big females; b. Small males and big males; c. Small females and small males; d. Small females and big males; e. Big females and small males; f. Big females and big males. Solid lines indicate 95% confidence intervals under random labeling hypothesis, dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals under type independence hypothesis. |

雌树通过降低营养生长将更多的生物量分配于繁殖过程,因此同一植物种群雄树的平均胸径通常大于雌树(Delph,1999; Pickering,2000)。水曲柳雌、雄植株胸径大小无显著差异,可能与林分仍处于中龄林阶段,雌雄植株分化尚不显著有关。水曲柳雌、雄植株具有相似的大小结构,与其他雌雄异株树种的研究结论一致(Melampy et al., 1977; Bullock,1982; Bullock et al., 1983; Opler et al., 1978; Thomas et al., 1993; Wheelwright et al., 1992; Morellato,2004)。雌雄植株初次开花时通常具有不同的初始植株大小(Korpelainen,1992; Antos et al., 1999; Delph,1999; Pickering,2000)。新热带区大量研究显示,雌雄异株植物种群性比未显著偏离1:1 (Bullock,1982; Bullock et al., 1981; 1983; Wheelwright et al., 1992; Morellato,2004)。Delph (1999)认为长寿命的灌木和乔木的种群性比通常偏雄。次生林中水曲柳种群性比未显著偏离1:1,并且大多数径级内雌树多于雄树,这可能与雌树的早熟现象有关。

水曲柳雌树和雄树主要呈聚集性分布,是由水曲柳种子有限的传播能力决定(韩有志等,2002)。水曲柳幼树与雌树之间并未表现出显著相关性,意味着水曲柳母树周围并不是水曲柳幼树建立的“安全生境”。水曲柳幼树与雄树在空间上相互独立,与水曲柳种子传播能力差、雄树周围种子少有关。大量研究证明雌雄异株植物的不同性别个体在占有空间或环境利用上存在差异,如个体较小的下层树种(Cavigelli et al., 1986)、杂性异株树种(Sakai et al., 1983)以及一些冠层树种(Wheelwright et al., 1992; Nanami et al., 2005)都存在雌、雄个体空间排斥现象。雌树和雄树不同的微环境偏好构成了雌雄异株植物的一种重要进化优势(Lloyd et al., 1977; Cox,1981)。本文同样检验到水曲柳雌树和雄树存在空间分离现象。水曲柳不同性别植株之间的竞争作用制约了水曲柳小植株(5 cm < DBH < 25 cm)出现在相对性别的大植株(DBH≥25 cm)附近,从而导致水曲柳形成与性别相关的空间分布格局。

韩有志, 王政权. 2002. 天然次生林中水曲柳种子的扩散格局[J]. 植物生态学报, 26(1): 51-57. |

张春雨, 赵秀海, 夏福才. 2008. 长白山次生林树种空间分布及环境解释[J]. 林业科学, 44(8): 1-8. DOI:10.11707/j.1001-7488.20080801 |

张春雨, 赵秀海, 赵亚洲. 2009. 长白山温带森林不同演替阶段群落结构特征研究[J]. 植物生态学报, 33(6): 1090-1100. |

Alliende M C, Harper J L. 1989. Demographic studies of a dioecious tree: Ⅰ.Colonization, sex and age structure of a population of Salix cinerea[J]. Journal of Ecology, 77: 1029-1047. DOI:10.2307/2260821 |

Antos J A, Allen G A. 1999. Patterns of reproductive effort in male and female shrubs of Oemleria cerasiformis: A 6-year study[J]. Journal of Ecology, 87(1): 77-84. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2745.1999.00331.x |

Bullock S H, Bawa K S. 1981. Sexual dimorphism and the annual flowering pattern in Jacaratia dolichaula(D.Smith) Woodson (Caricaceae) in a Costa Rican rain forest[J]. Ecology, 62: 1494-1504. DOI:10.2307/1941506 |

Bullock S H, Beach J H, Bawa K S. 1983. Episodic flowering and sexual dimorphism in Guarea rhopalocarpa in a Costa Rican rain forest[J]. Ecology, 64: 851-861. DOI:10.2307/1937208 |

Bullock S H. 1982. Population structure and reproduction in the Neotropical dioecious tree Compsoneura sprucei[J]. Oecologia, 55: 238-242. DOI:10.1007/BF00384493 |

Cavigelli M, Poulos M, Lacey E, et al. 1986. Sexual dimorphism in a temperate dioecious tree, Ilex montana(Aquifoliaceae)[J]. American Midland Naturalist, 115: 397-406. DOI:10.2307/2425875 |

Cox P A. 1981. Niche partitioning between sexes of dioecious plants[J]. American Naturalist, 117(3): 295-307. DOI:10.1086/283707 |

Delph L F, Galloway L F, Stanton M L. 1996. Sexual dimorphism in flower size[J]. Am Nat, 148(2): 299-320. DOI:10.1086/285926 |

Delph L F, Knapczyk F N, Taylor D R. 2002. Among-population variation and correlations in sexually dimorphic traits of Silene latifolia[J]. J Evol Biol, 15(6): 1011-1020. DOI:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00467.x |

Delph L F. 1999. Sexual dimorphism in life history // Geber M A, Dawson T E, Delph L F.Gender and sexual dimorphism in flowering plants[J]. Berlin: Springer-Verlag: 149-173. |

Diggle P J. 1983. Statistical analysis of spatial point patterns[M]. New York: Academic Press.

|

Gauquelin T, Bertaudière-Montès V, Badri W, et al. 2002. Sex ratio and sexual dimorphism in mountain dioecious thuriferous juniper(Juniperus thurifera L., Cupressaceae)[J]. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 138(2): 237-244. DOI:10.1046/j.1095-8339.2002.138002237.x |

Gehring J L, Monson R K. 1994. Sexual differences in gas exchange and response to environmental stress in dioecious Silene latifolia(Caryophyllaceae)[J]. American Journal of Botany, 81(2): 166-177. DOI:10.2307/2445630 |

Goreaud F, Pélissier R. 2003. Avoiding misinterpretation of biotic interactions with the intertype K12 -function: population independence vs.random labelling hypotheses[J]. Journal of Vegetation Science, 14(5): 681-692. |

Goto S, Iwata H, Shibano S, et al. 2005. Fruit shape variation in Fraxinus mandshurica var.japonica characterized by elliptic fourier descriptors and its effect on flight duration[J]. Ecological Research, 20(6): 733-738. DOI:10.1007/s11284-005-0090-5 |

Goto S, Shimatani K, Yoshimaru H, et al. 2006. Fat-tailed gene flow in the dioecious canopy tree species, Fraxinus mandshurica var.japonica revealed by microsatellites[J]. Molecular Ecology, 15(10): 2985-2996. DOI:10.1111/mec.2006.15.issue-10 |

Haase P. 1995. Spatial pattern analysis in ecology based on Ripley's K-function: Introduction and methods of edge correction[J]. Journal of Vegetation Science, 6(4): 575-582. DOI:10.2307/3236356 |

Korpelainen H. 1992. Patterns of phenotypic variation and sexual size dimorphism in Rumex acetosa and R.acetosella[J]. Botanica Helvetica, 102: 109-120. |

Lloyd D G, Webb C J. 1977. Secondary sex characters in plants[J]. Botanical Reviews, 43(2): 177-216. DOI:10.1007/BF02860717 |

Melampy M N, Howe H F. 1977. Sex ratio in the tropic tree Triplaris americana(Polygonaceae)[J]. Evolution, 31: 867-872. DOI:10.1111/evo.1977.31.issue-4 |

Morellato L P C. 2004. Phenology, sex ratio, and spatial distribution among dioecious species of Trichilia (Meliaceae)[J]. Plant Biology, 6(4): 491-497. DOI:10.1055/s-2004-817910 |

Nanami S, Kawaguchi H, Yamakura T. 2005. Sex ratio and genderdependent neighboring effects in Podocarpus nagi, a dioecious tree[J]. Plant Ecology, 177(2): 209-222. DOI:10.1007/s11258-005-2210-2 |

Opler P A, Bawa K S. 1978. Sex ratio in tropical forest trees[J]. Evolution, 32(4): 812-821. DOI:10.1111/evo.1978.32.issue-4 |

Peterson C J, Squiers E R. 1995. Competition and succession in an aspen-white-pine forest[J]. Journal of Ecology, 83: 449-457. DOI:10.2307/2261598 |

Pickering C M, Hill W. 2002. Reproductive ecology and the effect of altitude on sex ratios in the dioecious herb Aciphylla simplicifolia (Apiaceae)[J]. Aust J Bot, 50(3): 289-300. DOI:10.1071/BT01043 |

Pickering C M. 2000. Sex-specific differences in floral display and resource allocation in Australian alpine dioecious Aciphylla glacialis (Apiaceae)[J]. Aust J Bot, 48: 81-91. DOI:10.1071/BT97121 |

Ripley B D. 1976. The second-order analysis of stationary point processes[J]. Journal of Applied Probability, 13: 255-266. DOI:10.1017/S0021900200094328 |

Sakai A K, Oden N L. 1983. Spatial pattern of sex expression in silver maple(Acer saccharinum L.):Morisita's index and spatial autorrelation[J]. American Naturalist, 122: 489-508. DOI:10.1086/284151 |

Takahashi Y, Goto S, Kasahara H, et al. 2001. Sex expressions and size structures of a dioecious canopy tree species, Fraxinus mandshurica var.japonica[J]. Journal of the Japanese Forestry Society, 83(4): 334-339. |

Thomas S C, LaFrankie J V. 1993. Sex, size and interyear variation in flowering among dioecious trees of the Malayan rain forest[J]. Ecology, 74(5): 1529-1537. DOI:10.2307/1940080 |

Ueno N, Seiwa K. 2003. Gender-specific shoot structure and functions in relation to habitat conditions in a dioecious tree, Salix sachalinensis[J]. Journal of Forest Research, 8(1): 9-16. DOI:10.1007/s103100300001 |

Wheelwright N T, Bruneau A. 1992. Population sex ratio and spatial distribution of Ocotea tenera (Lauraceae) trees in a tropical forest[J]. Journal of Ecology, 80: 425-432. DOI:10.2307/2260688 |

Zhang C, Zhao X, Gao L, et al. 2009. Gender, neighboring competition and habitat effect on the stem growth in dioecious Fraxinus mandshurica trees in a northern temperate forest[J]. Annuals of Forest Science, 66(8): 812p1-812p9. |

2010, Vol. 46

2010, Vol. 46