文章信息

- 朱凡, 王光军, 田大伦, 闫文德, 项文化, 梁小翠

- Zhu Fan, Wang Guangjun, Tian Dalun, Yan Wende, Xiang Wenhua, Liang Xiaocui

- 马尾松人工林根呼吸的季节变化及影响因子

- Seasonal Variation of Root Respiration and the Controlling Factors in Pinus massoniana Plantation

- 林业科学, 2010, 46(7): 36-41.

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2010, 46(7): 36-41.

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2009-10-19

- 修回日期:2010-04-16

-

作者相关文章

2. 南方林业生态应用技术国家工程实验室 长沙 410004

2. National Engineering Laboratory for Applied Technology of Forestry & Ecology in South China Changsha 410004

森林生态系统作为陆地生物圈的主体,其碳贮量约为1 146 Pg (1 Pg=109 t),占全球陆地总碳贮量的46% (Watson et al., 2000),而森林土壤及其有机层贮存了森林生态系统39%的碳(Dixon et al., 1994)。土壤呼吸是全球碳循环的主要通量过程(Raich et al., 1992),包括根际呼吸(根和根际微生物呼吸)和异养呼吸(包括土壤微生物呼吸和土壤动物呼吸)(Tang et al., 2005),土壤碳循环过程的微弱变动将对全球CO2的排放总量产生显著影响(Burton et al., 2003)。在森林生态系统中,林木根呼吸占土壤呼吸的10%~90%(主要集中在40%~60%),释放光合作用固定CO2的8%~52%,是森林碳循环的重要途径之一(Atkin et al., 2000; 杨玉盛等, 2004a; 2004b; 姜丽芬等, 2004),森林生态系统的根呼吸和有机质分解损失的碳是森林碳收支的重要组成部分,但是关于不同有机碳输入和分解速率对土壤碳库和循环影响的长期定量研究一直是陆地生态系统碳循环研究的薄弱环节(Quideau et al., 2001; Johnston et al., 2004; Lajtha et al., 2005)。根系碳输入和凋落物分解作为土壤有机质的主要来源,在很大程度上影响着土壤有机质的形成以及对植物的养分供应和土壤CO2通量(Prescott, 2005),因此从土壤叶分解、根凋落物分解和土壤有机质中分离土壤自养呼吸(包括根的生长呼吸和维持呼吸)成为目前最为关注的焦点(Ngao et al., 2007)。特别是其主要组成部分土壤微生物和根系呼吸作用的影响机制是深入理解影响土壤呼吸作用的主导因子。尽管最近10年来总呼吸和异养呼吸受到相当大的关注,还是很少知道自养呼吸对总呼吸量的贡献(Lee et al., 2003)。

本试验以32年生马尾松(Pinus massoniana)人工林群落为研究对象,用挖壕去除植物根系试验方法,测定去除根系后样地的土壤表面CO2通量,并与对照进行比较,确定马尾松根系呼吸对土壤呼吸的贡献,增进对亚热带森林生态系统土壤碳库和碳循环过程的全面理解。

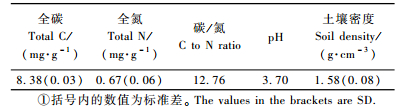

1 试验地概况试验地位于湖南省长沙市南郊的天际岭国家森林公园(113°01′—113°02′ E,28° 06′—28° 07′ N),核心区面积约4 356 hm2,海拔46~114 m,坡度为5°~25°。当地年平均气温17.2 ℃,1月最冷,平均4.7 ℃,极端最低温度-11.3 ℃; 7月最热,平均气温29.4 ℃,极端最高气温40.6 ℃; 无霜期为270~300天,日照时数年均1 677.1 h; 雨量充沛,年平均降雨量1 422 mm。属典型的亚热带湿润季风气候。其地层主要是第四纪更新世的冲积性网纹红土和砂砾,属典型红壤丘陵区,园内小生境众多,植物种类达2 200余种,植被以人工林为主。试验区土壤理化性质及根生物量、凋落物量见表 1。

|

|

2006年12月,在马尾松人工林群落中,选择4块小地形相似的地方,设置半径为15 m的圆形固定样地。样地郁闭度平均为0.8,林分平均密度为690株·hm-2,平均胸径18.7 cm,树高13.6 m,活枝下高7.8 m。群落主要组成成分以马尾松为优势种,混生有樟树(Cinnamomum camphora)、山矾(Symplocos caudata)、檫木(Sassafras tsumu)、大青(Clerodendrum cyrtophyllum)和青冈(Cyclobalanopsis glauca)等,草本植物有肾蕨(Nephrolepis auriculata)、酢浆草(Oxalis comiculata)、淡竹叶(Lophantherum gacile)、五节芒(Miscanthus floridulus)、鸡矢藤(Paederia scandens)和商陆(Phytolacca acinosa)等。

2 研究方法 2.1 试验样地的设置2006年12月,在马尾松群落中选择4块小地形相似的地方,设立半径为15 m的圆形固定样地。在每个固定样地内采用挖壕法(trenching),均匀设置3个0.6 m×0.6 m去除根系处理小区。挖壕法即用铁锹在小区四周挖壕沟,垂直挖0.6~0.8 m(看不到根系的深度),切断根(不移走)后插入6 mm厚塑料板以阻止根向小区内生长(Kuzyakov, 2006)。在去除根系处理小区的邻近地方,设置3个不做任何处理的PVC土壤环,作为对照点, 共计24个PVC土壤环测点。PVC土壤环的内径10.5 cm,高4.5 cm,平放压入土中2 cm左右。首次测量在土壤环安放24 h之后开始,并保持土壤环在整个测定期间位置不变(Wang et al., 2002)。

2.2 土壤呼吸及温度、湿度的测定采用Li-cor-6400-09(土壤呼吸室)连接到Li-6400便携式CO2/H2O分析系统(Li-cor Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA)测定土壤呼吸速率。在上午9: 00—11: 00每15天测定1次。2年共测定47次(2008年1月下旬因冰冻灾害少测定1次)。同时,用Li-6400-09的土壤温度探针测定土壤中5 cm的温度,用ECH2O Check(Decagon, USA)连接EC-5测定各样点土壤5 cm湿度(体积含水量,%)。

2.3 土壤理化性质测量土壤有机碳用重铬酸钾氧化-外加热法测定; 全氮用半微量凯氏法测定; pH值采用电位法测定; 土壤密度用环刀法测定(中国科学院南京土壤研究所,1978)。

2.4 数据统计分析所有的统计分析都在SPSS 13.0软件中进行,用ANOVA进行方差分析和多重比较检验土壤呼吸季节变化、土壤呼吸、温度和湿度的显著性,用SigmaPlot 9.0软件作图。土壤呼吸与温度之间关系采用如下指数模型(Luo et al., 2001; Raich et al., 1995):y=aebT, 式中,y为土壤呼吸速率; T为土壤温度; a是温度为0 ℃时的土壤呼吸(Luo et al., 2001); b为温度反应系数。Q10值通过下式确定(Xu et al., 2001):Q10=e10b。根呼吸贡献率(%)=100×(对照的土壤呼吸速率-去除根系土壤呼吸速率)/对照的土壤呼吸速率。

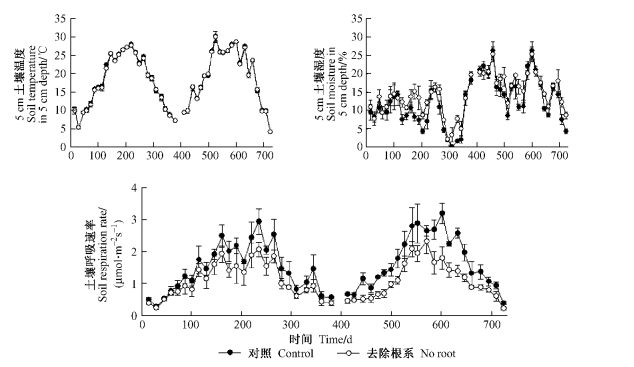

3 结果与分析 3.1 去除根系对土壤呼吸的影响马尾松群落去除根系与对照处理的土壤呼吸速率均呈现显著的季节性变化(P=0.000) (图 1),与土壤温度呈相似的曲线格局。去除根系与对照处理之间土壤呼吸差异极显著(P=0.000),2种处理2007年与2008年之间差异不显著(P=0.126)。2年去除根系与对照处理变化范围分别为0.25~2.33, 0.29~3.19 μmol ·m-2s-1,年均土壤呼吸速率分别为1.03, 1.56 μmol·m-2s-1。把土壤呼吸速率按非生长旺盛期(1—4,11和12月)和生长旺盛期(5—10月)分别检验(表 2),2007年和2008年非生长旺盛期土壤呼吸的差异性达到显著(P=0.020和P=0.003),生长旺盛期土壤呼吸的差异性达到极显著(P=0.000)。

|

图 1 马尾松群落去除根系和对照的土壤呼吸速率、温度和湿度季节动态 Figure 1 Seasonal dynamics of soil respiration rates, soil temperatures and moistures at 5 cm depth of different treatments with no root and control in P. massoniana community |

|

|

去除根系处理对马尾松群落土壤呼吸速率产生明显影响,导致土壤呼吸速率明显降低(图 1)。为减少去除根系对试验产生的干扰,去除2007年1—3月的测量数据。2007年去除根系土壤呼吸速率平均为1.32 μmol·m-2s-1,比对照1.73 μmol·m-2s-1低23.9%,2008年去除根系土壤呼吸速率平均为1.09 μmol·m-2s-1,比对照1.65 μmol·m-2s-1低33.9%。2年去除根系土壤呼吸速率降低12.2%~55.1%,平均降低28.3%。

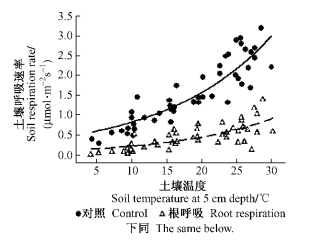

3.3 根呼吸与土壤温度的关系图 2表明,去除根系并没有改变土壤呼吸速率与5 cm土壤温度之间的关系,去除根系和对照处理的土壤呼吸速率与土壤温度之间均呈显著指数相关(P<0.001)。回归关系方程表达式分别为:

|

图 2 根呼吸和对照与5 cm土壤温度相关关系 Figure 2 Relationships between soil temperatures at 5 cm depth and soil respirations of different treatments with root respiration and control in P. massoniana community |

去除根系:y=0.302e0.060t R2=0.773,P=0.000;对照:y=0.205e0.072t R2=0.834,P=0.000。

用对照土壤呼吸减去去除根条根呼吸来估算根呼吸,拟合根呼吸与土壤温度之间呈显著指数相关,回归关系方程表达式为:

根呼吸:y=0.402e0.109t R20.601,P=0.000,式中: y表示土壤呼吸速率,t表示5 cm土壤温度。

本试验中,马尾松去除根系、对照土壤呼吸和根呼吸的温度敏感系数Q10值分别为1.82, 2.10和2.94,Q10值表现为:根呼吸>对照>去除根系。

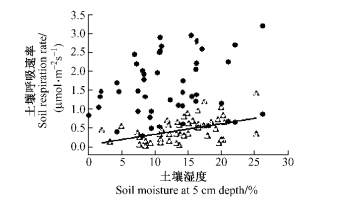

3.4 根呼吸与土壤湿度的关系马尾松林去除根系和对照处理的土壤呼吸速率与土壤湿度之间均呈二次曲线相关,但相关关系均不显著(P>0.05)。用估算的根呼吸速率与5 cm土壤湿度相关分析表明(图 3),根呼吸与土壤湿度之间呈显著线性相关(P=0.023)。回归关系方程表达式为:

|

图 3 根呼吸和对照与5 cm土壤湿度相关关系 Figure 3 Relationships between soil moistures at 5 cm depth and soil respirations of different treatments with root and control in P. massoniana community |

y=0.019w+0.209 R20.154,P=0.023,式中: y表示土壤呼吸速率,w表示5 cm土壤湿度。

4 讨论野外条件下,区分和量化土壤呼吸中的异养呼吸和根系自养呼吸非常困难,至今尚无理想的测定方法。挖壕法的理论前提是在挖壕的区域内完全抑制了植物根的呼吸活动(Lee et al., 2003)。挖壕法在小区四周挖壕沟切断根(不移走)后插入障碍物以阻止根向小区内生长(Kuzyakov, 2006)。与其他方法相比,对保留树的干扰较少,维持大部分野外条件(土壤温度日变化和季节变化、降水、凋落物、土壤的基质等),试验方法也相对简单(Hanson et al., 2000)。这种方法可信程度高,能连续估算土壤呼(Hanson et al., 2000; Bond-Lamberty et al., 2004)。

4.1 根呼吸对总土壤呼吸的贡献Amthor(2000)把根呼吸分为维持现有组织的维持呼吸(maintenance respiration)和用于构建新组织的生长呼吸(growth respiration)。植物根组织通过呼吸作用利用蛋白质和氨基酸进行新陈代谢,为根生物量合成、维持和离子吸收等提供能量(如ATP)和碳架(carbon skeletons)(盛浩等, 2007)。在本试验中,马尾松群落根呼吸对总土壤呼吸的贡献率为12.2%~55.1%,年均为28.3%。这一结果比先前Ewel等(1987)报道佛罗里达29年生湿地松(Pinus elliottii)群落和Epron等(1999)报道的30年生山毛榉(Fagus)林的根呼吸贡献率60%和52%低,与Wang等(2008)用挖壕法报道桤(Alnus cremastogyme)柏(Cupressus funebris)混交林的根呼吸贡献率在10.64%~56.10%(年均31.80%)接近。

产生这些差别的原因是由于根系呼吸产生的CO2量是由根生物量和单位根呼吸速率所决定的,并受到许多生物和非生物因子的调控,这些因子与植物的状况、生活史和环境有关(Amthor, 1991; Wang et al., 2002)。

4.2 土壤温度对根呼吸的影响本试验中马尾松根呼吸存在显著的季节变化,随土壤温度的升高而增大,并且两者之间均呈显著指数相关(图 2)。这是由于根呼吸对环境因子变化存在潜在响应,在自然条件下,植物根呼吸实质上是一系列酶促生化反应过程,受温度直接控制,土壤温度是植物根呼吸的主要驱动因子之一(Fahey et al., 2005; Maier et al., 2000; Bryla et al., 2001)。根据多年研究,土壤呼吸中组分不同,对温度敏感性不同。Boone等(1998)在哈佛森林土壤呼吸的Q10对去除根系处理的响应中,去除根系的Q10值为2.5,低于对照点3.5。在本试验中,马尾松去除根系Q10值与Boone等(1998)的结果是一致的,这主要是去除根系的土壤呼吸依然受土壤温度的影响,是光、温度和湿度对土壤呼吸过程的复合影响(Davidson et al., 2006)。温度通过影响土壤基质供应的季节性而影响枝条和根生长的物候学特征(Dunne et al., 2003),进而对土壤呼吸产生影响。本试验中马尾松根呼吸随温度的升高呈指数增加,这与Atkin等(2000)的结果一致,这是因为根呼吸在温度较低时主要是受生物化学反应限制,温度较高时,那些主要依赖扩散运输的代谢底物和代谢产物(如糖、氧气、CO2等)就成为限制因子。

4.3 土壤湿度对根呼吸的影响去除根系处理对土壤湿度产生一定影响。挖壕法明显干扰根系对土壤水分的吸收,去除根系样方内的土壤湿度年均值明显比对照高,与对照之间的差异显著。这与Ngao等(2007)在法国东北部用挖壕法估算根呼吸贡献率的结果是一致的。土壤湿度只有在最高和最低的情况下才会抵制土壤呼吸(Liu et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2004)。去除根系处理的微生物活动,当土壤水分过低时,微生物缺少必需的生存环境,产生CO2的量将会减少; 如果土壤水分过高,土壤孔隙减小,异氧呼吸所需氧气的进入以及呼吸产物CO2的排放都会受到限制(Zhang et al., 2005)。本试验中去除根系和对照处理的土壤呼吸速率与土壤湿度之间均呈二次曲线相关,但相关关系均不显著(P>0.05), 但估算出的根呼吸与土壤湿度之间呈显著线性相关(P=0.023)。这可能是由于土壤湿度的变化对根系生长呼吸和维持呼吸起到明显影响,进一步对根际的生理分泌产生影响,而根际微生物依赖于根系提供的活性碳源作为能量来源,根系呼吸的变化所引起的活性碳输入的变化,必然对微生物数量和活动产生影响。Li等(2004)在热带森林的试验表明,去除凋落物7年后微生物生物量显著减少了67%~69%。Simard等(1997)证明根系去除还可以显著降低外生真菌的种群数量、物种组成和根系感染率。

姜丽芬, 石福臣, 王化田, 等. 2004. 东北地区落叶松人工林的根系呼吸[J]. 植物生理学通讯, 40(1): 27-30. |

盛浩, 杨玉盛, 陈光水, 等. 2007. 植物根呼吸对升温的响应[J]. 生态学报, 27(4): 1596-1605. |

杨玉盛, 董彬, 谢锦升, 等. 2004a. 林木根呼吸及测定方法进展[J]. 植物生态学报, 28(3): 426-434. |

杨玉盛, 董彬, 谢锦升, 等. 2004b. 森林土壤呼吸及其对全球变化的响应[J]. 生态学报, 24(3): 583-591. |

中国科学院南京土壤研究所. 1978. 土壤理化分析[M]. 上海: 上海科学技术出版社.

|

Amthor J S. 2000. The McCree-de wit-penning de vries-thornley respiration paradigms: 30 years later[J]. Annals of Botany, 86: 1-20. DOI:10.1006/anbo.2000.1175 |

Amthor J S. 1991. Respiration in a future, higher CO2 world[J]. Plant, Cell and Environment, 14(1): 13-20. DOI:10.1111/pce.1991.14.issue-1 |

Atkin O K, Edwards E J, Loveys B R. 2000. Response of root respiration to changes in temperature and its relevance to global warming[J]. New Physiologist, 147: 141-154. DOI:10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00683.x |

Bond-Lamberty B, Wang C, Gower S T. 2004. A global relationship between the heterotrophic and autotrophic components of soil respiration?[J]. Global Change Biology, 10: 1756-1766. DOI:10.1111/gcb.2004.10.issue-10 |

Boone R D, Nadelhoffer K J, Canary J D, et al. 1998. Roots exert a strong influence on the temperature sensitivity of soil respiration[J]. Nature, 396: 570-572. DOI:10.1038/25119 |

Bryla D R, Bouma T J, Hartmond U, et al. 2001. Influence of temperature and soil drying on respiration of individual roots in citrus: integrating greenhouse observations into a predictive model for the field[J]. Plant Cell and Environment, 24: 781-790. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00723.x |

Burton A J, Pregitzer K S. 2003. Field measurements of root respiration indicate little to no seasonal temperature acclimation for sugar maple and red pine[J]. Tree Physiology, 23: 273-280. DOI:10.1093/treephys/23.4.273 |

Davidson E A, Richardson A D, Savage K E, et al. 2006. A distinct seasonal pattern of the ratio of soil respiration to total ecosystem respiration in a spruce-dominated forest[J]. Global Change Biology, 12: 230-239. DOI:10.1111/gcb.2006.12.issue-2 |

Dixon R K, Brown S, Houghton R A, et al. 1994. Carbon pools and flux of global forest ecosystems[J]. Science, 263: 185-190. DOI:10.1126/science.263.5144.185 |

Dunne J, Harte J, Taylor K. 2003. Response of subalpine meadow plant reproductive phonology to manipulated climate change and natural climate variability[J]. Ecological Monograph, 73: 69-86. DOI:10.1890/0012-9615(2003)073[0069:SMFPRT]2.0.CO;2 |

Epron D, Farque L, Lucot E, et al. 1999. Soil CO2 efflux in a beech forest: dependence on soil temperature and soil water content[J]. Annals of Forest Science, 56: 221-226. DOI:10.1051/forest:19990304 |

Ewel K C, Cropper W P, Gholz H L. 1987. Soil CO2 evolution in Florida slash pine plantations. Ⅱ. Importance of root respiration in a beech forest[J]. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 17: 330-333. DOI:10.1139/x87-055 |

Fahey T J, Yavitt J B. 2005. An in situ approach for measuring root-associated respiration and nitrate uptake of forest trees[J]. Plant and Soil, 272: 125-131. DOI:10.1007/s11104-004-4212-6 |

Hanson P J, Edwards N T, Garten C T, et al. 2000. Separating root and soil microbial contributions to soil respiration: A review of methods and observations[J]. Biogeochemistry, 48: 115-146. DOI:10.1023/A:1006244819642 |

Johnston C A, Groffman P, Breshears D D, et al. 2004. Carbon cycling in soil[J]. Frontiers in Ecology and Environment, 2: 522-528. DOI:10.1890/1540-9295(2004)002[0522:CCIS]2.0.CO;2 |

Kuzyakov Y. 2006. Sources of CO2 efflux from soil and review of partitioning methods[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 38: 425-448. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.08.020 |

Lajtha K, Crow S E, Yano Y, et al. 2005. Detritus controls on soil solution N and dissolved organic matter in soils: a field experiment[J]. Biogeochemistry, 76: 261-281. DOI:10.1007/s10533-005-5071-9 |

Lee M S, Nakane K, Nakatsubo T, et al. 2003. Seasonal changes in the contribution of root respiration to total soil respiration in a cool-temperate deciduous forest[J]. Plant and Soil, 255: 311-318. DOI:10.1023/A:1026192607512 |

Li Y Q, Xu M, Sun O J, et al. 2004. Effects of root and litter exclusion on soil CO2 efflux and microbial biomass in wet tropical forests[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 36: 2111-2114. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.06.003 |

Liu X Z, Wan S Q, Su B, et al. 2002. Response of soil CO2 efflux to water manipulation in a tall grass prairie ecosystem[J]. Plant and Soil, 240: 213-223. DOI:10.1023/A:1015744126533 |

Luo Y Q, Wan S Q, Hui D F, et al. 2001. Acclimatization of soil respiration to warming in a tall grass prairie[J]. Nature, 413: 622-625. DOI:10.1038/35098065 |

Maier C A, Kress L W. 2000. Soil CO2 evolution and root respiration in 11 year-old loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) plantations as affected by moisture and nutrient availability[J]. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 30: 347-359. DOI:10.1139/x99-218 |

Ngao J, Longdoz B, Granier A, et al. 2007. Estimation of autotrophic and heterotrophic components of soil respiration by trenching is sensitive to corrections for root decomposition and changes in soil water content[J]. Plant Soil, 301: 99-110. DOI:10.1007/s11104-007-9425-z |

Prescott C E. 2005. Do rates of litter decomposition tell us anything we really need to know?[J]. orest Ecology and Management, 220: 66-74. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2005.08.005 |

Quideau S A, Chadwick O A, Benesi A, et al. 2001. A direct link between forest vegetation type and soil organic matter composition[J]. Geoderma, 104: 41-60. DOI:10.1016/S0016-7061(01)00055-6 |

Raich J W, Schlesinger W H. 1992. The global carbon dioxide flux in soil respiration and its relationship to vegetation and climate[J]. Tellus, 44B(2): 81-99. |

Raich J W, Potter C S. 1995. Global patterns of carbon dioxide emissions from soils[J]. Global Biochemical Cycles, 9: 23-36. DOI:10.1029/94GB02723 |

Simard S W, Perry D A, Smith J E, et al. 1997. Effects of soil trenching on occurrence of ectomycorrhizas on Pseudotsuga menziesii seedlings grown in mature forests of Betula papyrifera and Pseudotsuga menziesii[J]. New Phytologist, 136: 327-340. DOI:10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00731.x |

Tang J W, Badocchi D D, Xu L K. 2005. Tree photosynthesis modulates soil respiration on a diurnal time scale[J]. Global Chang Ecology, 11: 1298-1304. DOI:10.1111/gcb.2005.11.issue-8 |

Wang H, Curtis P. 2002. A meta-analytical test of elevated CO2 effects on plant respiration[J]. Plant Ecology, 161: 251-261. DOI:10.1023/A:1020305006949 |

Wang X G, Zhu B, Wang Y Q, et al. 2008. Field measures of the contribution of root respiration to soil respiration in an alder and cypress mixed plantation by two methods: trenching method and root biomass regression method[J]. Europe Journal Forest Research, 127: 285-291. DOI:10.1007/s10342-008-0204-z |

Watson R T, Verardo D J. 2000. Land use, land-use change, and forestry, a special report on Climate Change[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

|

Xu L K, Baldocchi D D, Tang J W. 2004. How soil moisture, rain pulses, and growth alter the response of ecosystem respiration to temperature[J]. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 18: 1-10. |

Xu M, Qi Y. 2001. Spatial and seasonal variations of Q10 determined by soil respiration measurements at a Sierra Nevadan forest[J]. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 15: 687-696. DOI:10.1029/2000GB001365 |

Zhang W, Parker K, Luo Y, et al. 2005. Soil microbial responses to experimental atmospheric warming and clipping in a tallgrass prairie[J]. Global Change Biology, 11: 266-277. DOI:10.1111/gcb.2005.11.issue-2 |

2010, Vol. 46

2010, Vol. 46