文章信息

- 罗云建, 张小全, 王效科, 朱建华, 侯振宏, 张治军.

- Luo Yunjian, Zhang Xiaoquan, Wang Xiaoke, Zhu Jianhua, Hou Zhenhong, Zhang Zhijun

- 森林生物量的估算方法及其研究进展

- Forest Biomass Estimation Methods and Their Prospects

- 林业科学, 2009, 45(8): 129-134.

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2009, 45(8): 129-134.

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2008-03-21

-

作者相关文章

2. 中国林业科学研究院森林生态环境与保护研究所 北京 100091

2. Research Institute of Forest Ecology, Environment and Protection, Chinese Academy of Forestry Beijing 100091

森林生态系统作为陆地生态系统的主体, 在维护全球气候系统、调节全球碳平衡、减缓大气温室气体浓度上升等方面具有不可替代的作用(Woodwell et al., 1978)。森林生态系统植被所固定的碳量约占陆地植被总固碳量的82.5%(Sabine et al., 2004), 是森林固碳能力的重要标志, 也是评估森林碳收支的主要参数(IPCC, 2003; 2006)。《联合国气候变化框架公约》规定, 所有公约缔约方均需向公约缔约方大会递交履约信息通报(国家温室气排放清单)(UNFCCC, 1992)。生物量碳贮量及其变化是土地利用变化和林业国家温室气体排放清单的编制基础(IPCC, 2003; 2006)。此外, 《京都议定书》确立的清洁发展机制(CDM)下造林再造林活动也需要准确透明地评估活动所产生的核证减排量(CER), 其中生物量碳贮量及其变化在CER中具有重要地位(张小全等, 2005)。森林生物量及其变化的准确估算是核算生物量碳贮量及其变化的数据基础(IPCC, 2003; 2006)。本研究系统总结了森林生物量估算的常用方法, 并提出了今后我国在该领域的研究重点, 以期准确地估算不同尺度森林的生物量碳贮量及其变化, 更好地为陆地生态系统碳循环的研究、国家温室气体清单的编制和CDM造林再造林活动产生的CER核算服务。

1 森林生物量估算方法森林生物量可通过直接测量和间接估算2种途径得到(West, 2004):前者为收获法, 该方法虽然准确度最高, 但对生态系统的破坏性大且耗时费力; 后者是利用生物量模型(包括相对生长关系和生物量-蓄积量模型)、生物量估算参数及3S技术等方法进行估算, 其中生物量-蓄积量模型和生物量估算参数在大尺度森林生物量的估算中得到广泛应用(Somogyi et al., 2007)。

1.1 生物量模型 1.1.1 相对生长关系相对生长关系为植株结构和功能特征指标(如材积、生物量等)与易于测量的植株形态学变量(如胸径、树高等)间数量关系的统称(Niklas, 1994; Ketterings et al., 2001), 本研究特指生物量的相对生长关系。在森林生态系统的生物量和生产力估算中, 相对生长关系是最常见的方法(Ogawa, 1977; Gower et al., 1999)。

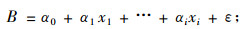

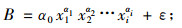

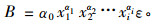

相对生长关系的构建通常采用平均标准木法或径级标准木法, 即先破坏性测量有限数量的标准木, 然后建立全部或部分生物量与易于获得的植株形态学变量(如胸径、树高等)间的数量关系(Salis et al., 2006)。Parresol (1999; 2001)将它们归纳为3种函数形式(公式1, 2和3), 并深入分析每种形式的异方差、可加性和一般性。

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

式中:B为生物量, 单位一般为kg或g; x1, x2, …, xi为植株形态学变量(如胸径、树高); α0, α1, …, αi为模型参数; ε为误差项。公式(1)和(2)最简化的形式分别为一元线性方程和一元幂函数, 其中幂函数是最常用的函数形式(Ketterings et al., 2001; Enquist et al., 2002)。

在相对生长模型中, 自变量除了常见的胸径和树高之外还有其他测量因子, 如林龄(Saint-André et al., 2005)和材积(唐守正等, 2000)。虽然自变量数目的增多常使生物量的估算更准确(Saint-André et al., 2005), 但也会加大野外调查时基本数据获取的难度, 从而影响相对生长模型的实用性。因此, 应充分考虑模型建立时的统计标准和模型的实用性(Niklas, 1994)。当前, 相对生长关系研究大体有2个方向:一是整理特定树种、立地等条件下的经验相对生长方程(Ter-Mikaelian et al., 1997; Zianis et al., 2005)和探索广义经验相对生长方程(Wirth et al., 2004; Zianis et al., 2004; Pilli et al., 2006; Muukkonen, 2007); 二是基于生物能量学、分形几何等理论, 探索整个生物界的相对生长规律, 以期最终揭示相对生长现象的本质(West et al., 1997; 1999a; 1999b)。

我国已阶段性整理了特定树种、立地等条件下的经验相对生长方程(陈传国等, 1989; 冯宗炜等, 1999), 但是大多数方程在构建过程中没有对异方差和可加性等加以控制和说明。国内学者也开始意识到这些问题, 提出了消除异方差的方法(张会儒等, 1999; 胥辉等, 2002), 如加权最小二乘法、增加可能造成异方差的自变量(如树高或林龄等)等; 引入材积自变量解决了以往生物量估算中各分量模型间不相容的问题(唐守正等, 2000), 实现了生物量模型和材积模型的兼容, 而且还结合了我国现行的森林资源清查方法。

1.1.2 生物量-蓄积量模型在森林生物量的组成中, 树干生物量所占的比例因树种、立地等条件的不同而有较大差异(Brown et al., 1984), 但树干生物量与树干材积和其他器官生物量存在很强的相关性(Whittaker et al., 1975; Brown, 1997), 从而奠定了生物量与蓄积量关系以及生物量估算参数的理论基础。

对生物量与蓄积量关系的认识经历了2个阶段:1)生物量与蓄积量之比为常数(Brown et al., 1984); 2)生物量与蓄积量的连续函数变化(Fang et al., 1998; Zhou et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2003)。国内外学者利用生物量与蓄积量的关系推算了某些气候带内森林的生物量(如热带)和国家(或区域)森林的生物量(如美国、中国、中国四川)(Brown et al., 1984; Smith et al., 2003; Fang et al., 1998; Pan et al., 2004; 黄从德等, 2007)。Fang等(1998)指出将生物量与蓄积量之比假定为恒定常数(Brown et al., 1984)是不恰当的, 并建立了与林龄无关的生物量-蓄积量线性关系。对许多森林类型而言, 建立这种线性关系的样本量明显不足, 而且将生物量与蓄积量的关系简单地处理为线性关系也存在争议(Zhou et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2005)。于是, 有些学者便开始从改进线性模型和构建新的关系模型2个角度来研究生物量与蓄积量的关系(Pan et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2003; 黄从德等, 2007)。Pan等(2004)改进了与林龄无关的生物量-蓄积量模型, 提出基于龄级的生物量-蓄积量线性模型, 明显提高了估算的准确性。Zhou等(2002)、Smith等(2003)和黄从德等(2007)则分别构建了与林龄无关的生物量-蓄积量双曲线模型、指数模型和幂函数模型。然而, Zhou等(2002)和Zhao等(2005)只建立我国5种森林类型的生物量-蓄积量双曲线模型:落叶松(Larix spp.)林、油松(Pinus tabulaeformis)人工林、马尾松(Pinus massoniana)人工林、杉木(Cunninghamia lanceolata)人工林和杨树(Populus spp.)人工林, 其他森林类型能否也可用双曲线模型描述仍需研究。上述所涉及的生物量与蓄积量关系的模型形式具体为:B=a+bV (Fang et al., 1998); B=V/(a+bV) (Zhou et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2005); B=a-be-cV (Smith et al., 2003); B=aVb (黄从德等, 2007)。式中:B为生物量(t·hm-2); V为蓄积量(m3·hm-2); a, b和c为回归系数。

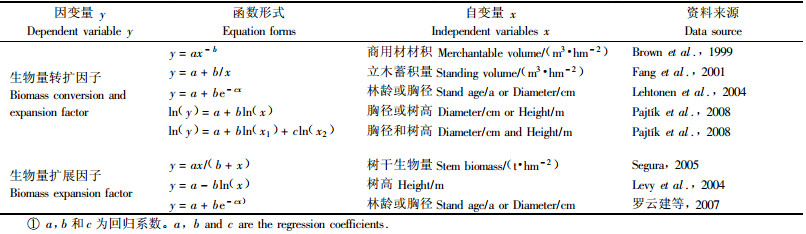

1.2 生物量估算参数生物量估算参数主要包括生物量转扩因子(biomass conversion and expansion factor, BCEF)、生物量扩展因子(biomass expansion factor, BEF)、根茎比(root:shoot ratio, R/S)和木材密度(wood density, WD)4个常用参数(Brown et al., 1999; Fang et al., 2001; Lehtonen et al., 2004; IPCC, 2006)。在生物量估算参数的发展过程中, 可分为平均生物量估算参数和连续生物量估算参数2个阶段。平均生物量估算参数是利用某森林类型生物量估算参数的平均值或范围估算森林生物量(Sharp et al., 1975; Johnson et al., 1983; Brown et al., 1984; Kauppi et al., 1992; Turner et al., 1995)。大量研究表明, 生物量估算参数的值不仅随森林类型的变化而变化, 而且在同一森林类型中也随林龄、林分密度、立地等条件的变化而变化(Kramer, 1982; Brown et al., 1999; Löewe et al., 2000; Köhl, 2000)。于是, 连续生物量估算参数应运而生, 即构建以林龄、蓄积量和器官生物量等指标为自变量, 生物量估算参数为因变量的连续函数关系(Schroeder et al., 1997; Fang et al., 2001; Lehtonen et al., 2004; Levy et al., 2004; 罗云建等, 2007)。

1.2.1 生物量转扩因子有学者利用生物量转扩因子推算了不同森林类型(如美国暖性阔叶林)和不同国家(或区域)森林的生物量(如中国、印度、瑞典、美国东部、挪威东南部)(Schroeder et al., 1997; Brown et al., 1999; Fang et al., 2001; Chhabra et al., 2002; Jalkanen et al., 2005; de Wit et al., 2006)。常用的生物量转扩因子定义主要有3种:1)地上生物量(t·hm-2)与商用材材积(m3·hm-2)之比(Schroeder et al., 1997; Brown et al., 1999; IPCC, 2006); 2)总生物量(包括地上和地下生物量)(t·hm-2)与立木蓄积量(m3·hm-2)之比(Fang et al., 2001); 3)器官生物量(树干、活枝、死枝、树叶、根桩、粗根、细根或整体)(t·hm-2)与树干材积(m3·hm-2)之比(Lehtonen et al., 2004; Pajtík et al., 2008)。可见, 利用生物量转扩因子可直接将蓄积量数据转换为器官生物量、地上生物量或总生物量。

生物量转扩因子的平均值从寒温带到热带湿润气候带有增加的趋势(IPCC, 2006), 而且很多研究表明, 它与林龄、胸径、树高、蓄积量等林分调查指标存在显著的负相关性(Brown et al., 1999; Fang et al., 2001; Lehtonen et al., 2004; Pajtík et al., 2008)。罗云建等(2007)通过研究中国落叶松林发现, 人工林的生物量转扩因子平均值大于天然林, 而且人工林的生物量转扩因子与林龄和胸径存在显著的负相关, 天然林却存在显著的正相关。林分起源是否也会影响其他森林类型的生物量转扩因子的值尚待进一步研究。目前所采用的生物量转扩因子与林分调查指标的函数形式见表 1。

|

|

为了将蓄积量数据转换为生物量数据, 除生物量转扩因子外, 还可先通过木材密度将蓄积量转换成相应的生物量, 然后利用生物量扩展因子将这部分生物量扩展到地上生物量和总生物量。不同树种木材密度值的差异最高可达数倍(中国林业科学研究院木材工业研究所, 1982; IPCC, 2006), 同一树种因环境差异引起的变化幅度一般在10%以内(成俊卿, 1985; 江泽慧等, 2001)。因此, 在将蓄积量转换成相应的生物量时, 应首先根据树种选择适合的木材密度, 并尽可能地与生长环境结合起来, 以期提高估算结果的准确性。

与木材密度相比, 生物量扩展因子的研究明显不足(Wang et al., 2001; Levy et al., 2004; Segura, 2005; 罗云建等, 2007)。生物量扩展因子定义也有3种:1)地上生物量(t·hm-2)与商用材部分的生物量(t·hm-2)之比(Levy et al., 2004; IPCC, 2006); 2)地上生物量(t·hm -2)与树干生物量(t·hm-2)之比(罗云建等, 2007); 3)总生物量(包括地上和地下生物量) (t·hm-2)与树干生物量(t·hm-2)之比(Wang et al., 2001; Segura, 2005)。从寒温带到热带, 阔叶林的生物量扩展因子平均值逐渐增加, 针叶林则无明显的变化趋势(IPCC, 2003); 同一气候带内阔叶林的生物量扩展因子平均值大于针叶林(IPCC, 2003)。目前, 生物量扩展因子随林分调查指标变化规律的报道仅限于少数国家的森林类型(如中国落叶松林、英国针叶林、哥斯达黎加热带湿润林)(Levy et al., 2004; Segura, 2005; 罗云建等, 2007), 这些研究表明生物量扩展因子与林龄、胸径、树高、树干生物量等林分调查指标存在显著的相关性(Levy et al., 2004; Segura, 2005; 罗云建等, 2007)。英国针叶林和哥斯达黎加热带湿润林的生物量扩展因子分别与树高和树干生物量存在显著的负相关(Levy et al., 2004; Segura, 2005)。罗云建等(2007)通过研究中国落叶松林发现, 人工林的生物量扩展因子平均值大于天然林, 而且人工林的生物量扩展因子与林龄和胸径存在显著的负相关, 天然林却存在显著的正相关。林分起源是否也会影响其他森林类型生物量扩展因子的值有待研究。目前所采用的生物量扩展因子与林分调查指标的函数形式见表 1。

1.2.3 根茎比根茎比通常定义为地下生物量与地上生物量之比(IPCC, 2006)。早期的研究一般假定根茎比为固定值(Bray, 1963), 后来的研究发现根茎比随树种、林龄、胸径、树高、林分密度和地上生物量等指标的变化而变化(Sanford et al., 1995; Cairns et al., 1997; Levy et al., 2004; Mokany et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2008)。根茎比随着林龄、胸径、树高和地上生物量的增加而减小, 随着林分密度的增加而增加(Cairns et al., 1997; Mokany et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2008)。在热带和温带森林中, 随着林龄的增加, 根茎比从幼龄林的0.30~0.50下降到过熟林的0.15~0.30(Ranger et al., 2001; Kraenzel et al., 2003; Laclau, 2003)。在中大尺度上, 非生物因素(如林分起源、年均降水量、土壤质地)是否会影响根茎比尚无定论(Cairns et al., 1997; Mokany et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2008; 罗云建等, 2007), 如Mokany等(2006)认为根茎比随着年均降水量的增加而减小, 随着粘土、壤土到砂土土壤质地的变化而有增加的趋势; Cairns等(1997)则认为年均降水量和土壤质地并不会显著影响根茎比(P>0.05)。

2 研究展望研究发现, 我国森林的生物量碳储量从20世纪70年代中期开始稳步增加(Fang et al., 2001; Pan et al., 2004), 但估算结果间存在很大的差异。森林生物量碳储量及其变化的估算又是以森林生物量及其变化为估算基础的(IPCC, 2003; 2006)。我国除了对生物量-蓄积量方程和生物量转扩因子的研究较为全面外, 经验相对生长关系的整合和生物量估算参数的全面研究目前还在初步阶段。考虑到国内目前的研究现状, 针对这2类常用的估算方法, 建议从以下3个方面开展工作。

1) 整合经验相对生长方程。首先, 收集整理大量报道中的经验相对生长方程, 有助于减少盲目性, 重复构建, 深刻理解相对生长的规律性; 其次, 对未说明异方差和可加性的相对生长方程, 量化其可信度和不确定性水平; 最后, 构建保证一定预测精度的立地普适和物种普适广义相对生长方程。另外, 还应及时修订或验证已有的生物量-蓄积量模型, 尽量克服样本量不足、方程形式等争议性问题, 从而提高方程的可信度和预测精度。

2) 系统研究生物量估算参数。首先, 针对我国各级森林资源清查资料和生物量实测数据的特点, 提出符合我国林业实际且具有可操作性的定义; 其次, 计算我国主要森林类型的生物量估算参数值, 构建生物量估算参数与林分调查指标的函数关系; 最后, 分析和量化非生物因素对生物量估算参数的影响程度。

3) 构建传统估算方法和3S(GPS, RS和GIS)技术相结合的生物量估算系统, 提高估算结果的准确性和可信度。

陈传国, 朱俊凤. 1989. 东北主要林木生物量手册. 北京: 中国林业出版社.

|

成俊卿. 1985. 木材学. 北京: 中国林业出版社.

|

冯宗炜, 王效科, 吴刚. 1999. 中国森林生态系统的生物量和生产力. 北京: 科学出版社.

|

黄从德, 张建, 杨万勤, 等. 2007. 四川森林植被碳储量的时空变化. 应用生态学报, 18(12): 2687-2692. |

江泽慧, 彭镇华. 2001. 世界主要树种木材科学特性. 北京: 科学出版社.

|

罗云建, 张小全, 侯振宏, 等. 2007. 我国落叶松林生物量碳计量参数的初步研究. 植物生态学报, 31(6): 1111-1118. |

唐守正, 张会儒, 胥辉. 2000. 相容性生物量模型的建立及其估计方法研究. 林业科学, 36(S1): 19-27. |

胥辉, 张会儒. 2002. 林木生物量模型研究. 昆明: 云南科学技术出版社.

|

张会儒, 唐守正, 王奉瑜. 1999. 与材积兼容的生物量模型的建立及其估计方法研究. 林业科学研究, 12(1): 53-59. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-1498.1999.01.010 |

张小全, 李怒云, 武曙红. 2005. 中国实施清洁发展机制造林和再造林项目的可行性和潜力. 林业科学, 41(5): 139-143. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-7488.2005.05.025 |

中国林业科学研究院木材工业研究所. 1982. 中国主要树种的木材物理力学性质. 北京: 中国林业出版社.

|

Bray J R. 1963. Root production and the estimation of net productivity. Canadian Journal of Botany, 41: 65-72. DOI:10.1139/b63-007 |

Brown S L, Schroeder P E. 1999. Spatial patterns of aboveground production and mortality of woody biomass for eastern U.S. forests. Ecological Applications, 9: 968-980. |

Brown S, Lugo A E. 1984. Biomass of tropical forests: a new estimate based on forest volumes. Science, 233: 1290-1293. |

Brown S. 1997. Estimating biomass and biomass change of tropical forests: a primer. [EB/OL]. [2005-03-23]. http://www.fao.org/docrep/w4095e/w4095e00.htm. http://www.fao.org/docrep/w4095e/w4095e00.htm

|

Cairns M A, Brown S, Helmer E H, et al. 1997. Root biomass allocation in the world's upland forests. Oecologia, 111: 1-11. DOI:10.1007/s004420050201 |

Chhabra A, Palria S, Dadhwal V K. 2002. Growing stock-based forest biomass estimate for India. Biomass and Bioenergy, 22: 187-194. DOI:10.1016/S0961-9534(01)00068-X |

de Wit H A, Palosuo T, Hylen G, et al. 2006. A carbon budget of forest biomass and soils in southeast Norway calculated using a widely applicable method. Forest Ecology and Management, 225(1-3): 15-26. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2005.12.023 |

Fang J Y, Chen A P, Peng C H, et al. 2001. Changes in forest biomass carbon storage in China between 1949 and 1998. Science, 291: 2320-2322. |

Fang J Y, Wang G G, Liu G H, et al. 1998. Forest biomass of China: an estimate based on the biomass-volume relationship. Ecological Applications, 8(4): 1084-1091. |

Gower S T, Kucharik C J, Norman J M. 1999. Direct and indirect estimation of leaf area index, fAPAR, and net primary production of terrestrial ecosystems—a real or imaginary problem?. Remote Sensing of Environment, 70(1): 29-51. DOI:10.1016/S0034-4257(99)00056-5 |

IPCC. 2003. Good practice guidance for land use, land-use change and forestry. [EB/OL]. [2004-05-01]. http://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/gpglulucf/gpglulucf.html. http://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/gpglulucf/gpglulucf.html

|

IPCC. 2006. 2006 IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventory. [EB/OL ]. [2006-12-15]. http://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/index.html. http://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/index.html

|

Jalkanen A, Mäkipää R, Ståhl G, et al. 2005. Estimation of the biomass stock of tree in Sweden: comparison of biomass equations and age-dependent biomass expansion factors. Annals of Forest Science, 62: 845-851. DOI:10.1051/forest:2005075 |

Johnson W C, Sharpe D M. 1983. The ratio of total to merchantable forest biomass and its application to the global carbon budget. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 13: 372-383. DOI:10.1139/x83-056 |

Kauppi P E, Mielikainen K, Kusela K. 1992. Biomass and carbon budget of European forests, 1971 to 1990. Science, 256: 70-74. DOI:10.1126/science.256.5053.70 |

Ketterings Q M, Coe R, van Noordwijk M, et al. 2001. Reducing uncertainty in the use of allometric biomass equations for predicting aboveground biomass in mixed secondary forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 146: 199-209. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00460-6 |

Köhl M. 2000. Reliability and comparability of TBFRA 2000 results. [EB/OL]. [2004-05-01]. http://www.unece.org/timber/fra/pdf/fullrep.pdf. http://www.unece.org/timber/fra/pdf/fullrep.pdf

|

Kraenzel M, Castillo A, Moore T, et al. 2003. Carbon storage of harvest-age teak (Tectona grandis) plantations, Panama. Forest Ecology and Management, 173(1-3): 213-225. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1127(02)00002-6 |

Kramer P J. 1982. Carbon dioxide concentration, photosynthesis, and dry matter production. Bioscience, 31: 29-33. |

Laclau P. 2003. Root biomass and carbon storage of ponderosa pine in the northwest Patagonia plantations. Forest Ecology and Management, 173(1-3): 353-360. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1127(02)00012-9 |

Lehtonen A, Mäkipää R, Heikkinen J, et al. 2004. Biomass expansion factors (BEFs) for Scots pine, Norway spruce and birch according to stand age for boreal forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 188: 211-224. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2003.07.008 |

Levy P E, Hale S E, Nicoll B C. 2004. Biomass expansion factors and root: shoot ratios for coniferous tree species in Great Britain. Forestry, 77(5): 421-430. DOI:10.1093/forestry/77.5.421 |

Löewe H, Seufert G, Raes F. 2000. Comparison of methods used within Member States for estimating CO2 emissions and sinks according to UNFCCC and EU Monitoring Mechanism: forest and other wooded land. Biotechnologie, Agronomie, Société et Environnement, 4(4): 315-319. |

Mokany K, Raison J R, Prokushkin S A. 2006. Critical analysis of root: shoot ratios in terrestrial biomes. Global Change Biology, 12: 84-96. DOI:10.1111/gcb.2006.12.issue-1 |

Muukkonen P. 2007. Generalized allometric volume and biomass equations for some tree species in Europe. European Journal of Forest Research, 126: 157-166. DOI:10.1007/s10342-007-0168-4 |

Niklas K J. 1994. Plant allometry: the scaling of form and process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

|

Ogawa H. 1977. Principle and methods of estimating primary production in forests // Shidei T, Kora T. Primary productivity of Japanese forests—productivity of terrestrial communities. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 29-38.

|

Pajtík J, Konpka B, Lukac M. 2008. Biomass functions and expansion factors in young Norway spruce (Picea abies [L.] Karst) trees. Forest Ecology and Management, 256: 1096-1103. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2008.06.013 |

Pan Y D, Luo T X, Birdsey R, et al. 2004. New estimates of carbon storage and sequestration in China's forests: effects of age-class and method on inventory-based carbon estimation. Climatic Change, 67: 211-236. DOI:10.1007/s10584-004-2799-5 |

Parresol B R. 1999. Assessing tree and stand biomass: a review with examples and critical comparisons. Forest Science, 45(4): 573-593. |

Parresol B R. 2001. Additivity of nonlinear biomass equations. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 31: 865-878. DOI:10.1139/x00-202 |

Pilli R, Anfodillo T, Carrer M. 2006. Towards a functional and simplified allometry for estimating forest biomass. Forest Ecology and Management, 237: 583-593. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2006.10.004 |

Ranger J, Gelhaye D. 2001. Belowground biomass and nutrient content in a 47-year-old Douglas-fir plantation. Annals of Forest Science, 58: 423-430. DOI:10.1051/forest:2001135 |

Sabine C L, Heimann M, Artaxo P, et al. 2004. Current status and past trends of the global carbon cycle//Field C B, Raupach M R, MacKenzie S H. The global carbon cycle: integrating humans, climate and the natural world. Washington: Island Press, 17-44.

|

Saint-André L, M'Bou A T, Mabiala, et al. 2005. Age-related equations for above-and below-ground biomass of a Eucalyptus hybrid in Congo. Forest Ecology and Management, 205: 199-214. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2004.10.006 |

Salis S M, Assis M A, Mattos P P, et al. 2006. Estimating the a boveground biomass and wood volume of savanna woodlands in Brazil's Pantanal wetlands based on allometric correlations. Forest Ecology and Management, 228: 61-68. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2006.02.025 |

Sanford R L Jr, Cuevas E. 1995. Root growth and rhizosphere interactions in tropical forests // Mulkey S S, Chazdon R L, Smith A P. Tropical forest plant ecophysiology. New York: Chapman and Hall, 268-300. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-1-4613-1163-8_10

|

Schroeder P E, Brown S, Mo J, et al. 1997. Biomass estimation f or temperate broadleaf forests of the United States using inventory data. Forest Science, 43(3): 424-434. |

Segura M. 2005. Allometric models for tree volume and total aboveground biomass in a tropical humid forest in Costa Rica. Biotropica, 37(1): 2-8. DOI:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2005.02027.x |

Sharp D D, Lieth H, Whigham D. 1975. Assessment of regional productivity in North Carolina//Lieth H, Whittacker R H. Primary productivity of the biosphere. New York: Springer-Verlag, 131-146. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-3-642-80913-2_6

|

Smith J E, Heath L S, Jenkins J S. 2003. Forest volume-to-biomass models and estimates of mass for live and standing dead trees of U.S. forests. [EB/OL]. [2005-10-07]. http://www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/pubs/5179. http://www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/pubs/5179

|

Somogyi Z, Cienciala E, Mäkipää R, et al. 2007. Indirect methods of large-scale forest biomass estimation. European Journal of Forest Research, 126: 197-207. DOI:10.1007/s10342-006-0125-7 |

Ter-Mikaelian M T, Korzukhin M D. 1997. Biomass equations for sixty-five North American tree species. Forest Ecology and Management, 97: 1-24. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1127(97)00019-4 |

Turner D P, Koepper G J, Harmon M E, et al. 1995. A carbon budget for forests of the conterminous United States. Ecological Applications, 5: 421-436. DOI:10.2307/1942033 |

UNFCCC. 1992. The united nations framework convention on climate change. [EB/OL]. [2004-09-10]. http://unfccc.int/essential_background/convention/background/items/2853.php. http://unfccc.int/essential_background/convention/background/items/2853.php

|

Wang X K, Feng Z W, Ouyang Z Y. 2001. The impact of human disturbance on vegetative carbon storage in forest ecosystems in China. Forest Ecology and Management, 148: 117-123. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00482-5 |

Wang X P, Fang J Y, Zhu B. 2008. Forest biomass and root-shoot allocation in northeast China. Forest Ecology and Management, 255: 4007-4020. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2008.03.055 |

West G B, Brown J H, Enquist B J. 1997. A general model for the origin of allometric scaling laws in biology. Science, 276: 122-126. DOI:10.1126/science.276.5309.122 |

West G B, Brown J H, Enquist B J. 1999a. The fourth dimension of life: fractal geometry and allometric scaling of organisms. Science, 284: 1677-1679. DOI:10.1126/science.284.5420.1677 |

West G B, Brown J H, Enquist B J. 1999b. A general model for the structure and allometry of plant vascular systems. Nature, 400: 664-667. DOI:10.1038/23251 |

West P W. 2004. Tree and Forest Measurement. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

|

Whittaker R H, Likens G E. 1975. Methods of assessing terrestrial productivity. New York: Springer-Verlag, 305-328.

|

Wirth C, Schumacher J, Schulze E D. 2004. Generic biomass functions for Norway spruce in central Europe—a meta-analysis approach toward prediction and uncertainty estimation. Tree Physiology, 24: 121-139. DOI:10.1093/treephys/24.2.121 |

Woodwell G M, Whittacker R H, Reiners W A, et al. 1978. The biota and the world carbon budget. Science, 199: 141-146. DOI:10.1126/science.199.4325.141 |

Zhao M, Zhou G S. 2005. Estimation of biomass and net primary productivity of major planted forests in China based on forest inventory data. Forest Ecology and Management, 207: 295-313. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2004.10.049 |

Zhou G S, Wang Y H, Jiang Y L, et al. 2002. Estimating biomass and net primary production from forest inventory data: a case study of China's Larix forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 169: 149-157. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1127(02)00305-5 |

Zianis D, Mencuccini M. 2004. On simplifying allometric analyses of forest biomass. Forest Ecology and Management, 187: 311-332. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2003.07.007 |

Zianis D, Muukkonen P, Mäkipää R, et al. 2005. Biomass and stem volume equations for tree species in Europe. Silva Fennica Monographs, 4: 63. |

2009, Vol. 45

2009, Vol. 45