文章信息

- 陈辉.

- Chen Hui.

- 化学信息素对小蠹虫入侵危害的调控

- THE REGULATION ROLE OF SEMIOCHEMICALS IN THE HOST SELECTION AND COLONIZATION OF BARK BEETLES

- 林业科学, 2003, 39(6): 154-158.

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2003, 39(6): 154-158.

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2002-01-07

-

作者相关文章

森林生态系统多种复杂的信息化学物质(semiochemical)不仅影响和决定着森林生态系统内生物的时空结构与分布,而且决定着森林生态系统内生物营养利用的层次、数量和质量。小蠹虫作为森林生态系统内最主要的初级营养消费者,对寄主树木的定向选择行为受到森林生态系统内树木挥发性物质的影响,寄主树木挥发性物质决定着小蠹虫对寄主树木、林分结构和寄主树木部位的成功选择。而另一方面,小蠹虫自身和寄主树木次生代谢物质的联合作用,决定了小蠹虫入侵寄主树木的时空动态、种群动态和繁殖策略。小蠹抗聚集信息素(也称空间信息素或扩散信息素)又可调节小蠹虫的种群密度(Borden,1977)。小蠹虫对寄主树木的选择和入侵危害整个过程(包括扩散、选择、定居和繁殖)是在森林生态系统内树木次生代谢物质和小蠹虫化学信息素的综合调控下完成的(Amman,1998)。

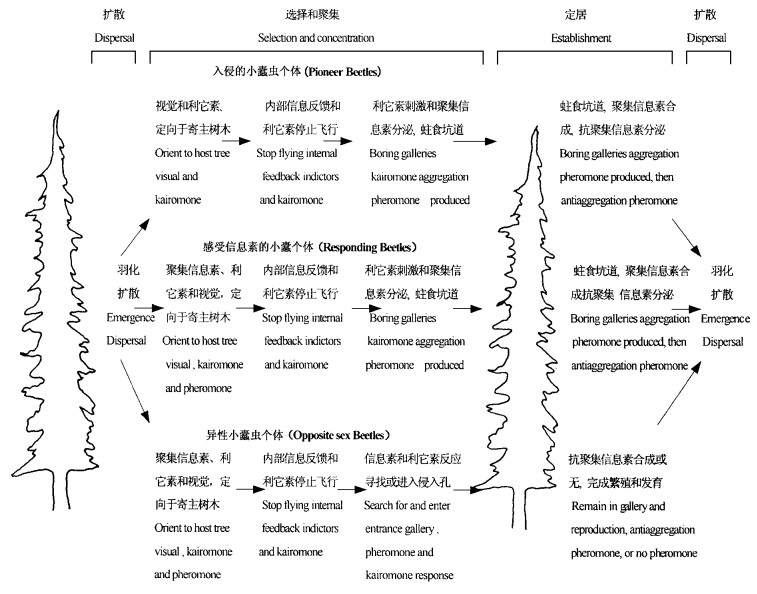

1 信息素对小蠹虫危害行为的调控Visser(1986)评述了森林生态系统内植物释放的次生挥发性物质对小蠹虫和其它植食性昆虫的引诱和驱避等作用,认为小蠹虫对寄主树木的选择受到小蠹虫和寄主树木挥发性物质的联合影响,针叶树木树脂中含量较高的萜烯类物质及其衍生物,可以引诱小蠹虫的入侵危害。Birch(1980)提出昆虫的取食和交配行为受到寄主植物、昆虫相关的微生物和昆虫信息素的影响和调控。Landolt和Phillips(1997)认为鞘翅目昆虫性信息素的分泌与寄主树木组织,昆虫的消化和生理代谢,以及消化道内微生物的分解和转化相关。Wood(1982)、Borden(1982)和Amman(1995)将小蠹虫的入侵危害划分为扩散、选择、聚集和定居四个阶段,并认为信息素对小蠹虫的调控集中于扩散、选择和聚集阶段。Borden(1982)则评述了化学信息素在小蠹虫入侵和危害中的作用(图 1)。

|

图 1 化学信息素在小蠹虫选择和入侵寄主树木中的作用 Fig. 1 Semiochemicals factors influencing behavior of Bark Beetles in host selection and mass attack |

Visser(1986)将小蠹虫对寄主树木的选择过程分为定向、着陆、探索、取食和产卵五个步骤。小蠹虫的羽化是在温度的诱导和昼夜节律调控下完成的,而对寄主树木和林分结构的选择,以及在林分内的分布则受到寄主树木和小蠹虫化学信息素的影响。Borden et al.(1969)研究表明黑条木小蠹(Trypodendron lineatum)和黄杉大小蠹(Dendroctonus pseudotsugae)在没有寄主树木次生挥发性物质的诱导时,通常需要30~90min的飞行时间,以感应和接受林分内寄主树木的挥发性化学物质,当接受到寄主树木次生性化学物质的引诱则迅速停止飞行,并着陆于寄主树木。Johnson(1978)认为瘤额大小蠹(D. frontalis)越冬羽化的成虫需要长距离的飞行,以接受寄主树木和小蠹虫信息素的刺激和引诱。Hedden et al.(1977)认为子代小蠹虫在对寄主树木的选择和着陆中,首先选择已被小蠹虫危害的寄主树木,这表明被害寄主树木具有更强的引诱能力。Borden(1982;1995)和Wood(1982)指出小蠹虫在森林生态系统内的扩散行为和对寄主树木的定向着陆行为是寄主树木和小蠹虫化学信息素综合调控的结果。

1.2 信息素对小蠹虫选择行为的调控Person(1930),Wood(1982)和Borden(1982;1995)将寄主树木对小蠢虫的引诱分为初级引诱和次级引诱,其中初级引诱主要表现在寄主树木的次生单萜类物质,而次级引诱则主要是入侵寄主树木的小蠢虫和寄主树木代谢物质的联合作用。Graham(1968)揭示出寄主树木厌氧性醇类代谢物质和单萜类物质(如a-烯)对食菌小具有初级引诱作用。Rudinsky(1966),Wood(1982)和Ferell(1971)证实寄主树木萜烯类物质对黄杉大小蠹、弱瘤小蠹(Scolytus ventralis)、西松大小蠹(D. brevicomis)和黑山大小蠹(D. ponderosae)具有明显的初级引诱作用。

Borden(1982;1995)认为寄主树木分泌的利它素在对小蠹虫的次级引诱作用随寄主树木生理生化特性而变化。初期性小蠹(如大小蠹属的种类)将寄主树木分泌的单萜类物质作为寄主树木初级引诱的增效剂,以便迅速克服寄主树木树脂流动的抗性; 而次期性小蠹(如齿小蠹属Ips的种类)则将寄主树木分泌的利它素作为主要的次级引诱剂,集中入侵寄主树木树脂压较低的衰弱木、采伐木和树冠上部的枝条等部位; 食菌小蠹也将寄主树木分泌的醇类和α-蒎烯作为寄主树木选择的增效剂。Amman(1995),Borden(1995),Paine(1995),Salom(1995)等研究表明,寄主树木分泌的Geraniol、Limonene、Methyl chavicol、Myrcene,α-Pinene、Limonene、Camphene和Ethanol能够引诱南部松齿小蠹(Ips grandicollis),黄杉大小蠹和黑条木小蠹在寄主树木上的产卵。Hobson(1995)证明植物次生挥发性物质Methylchavicol是一种高效的抗小蠹聚集信息素。Dicken(1992)和Schroeder(1992)发现阔叶常绿树木的挥发性物质可明显地减少美东最小齿小蠹(Ips avulsus)对寄主树木的危害;林分内欧洲山杨的次生性挥发物质可减少纵坑切梢小蠹(Tomicus piniperda)和细干小蠹(Hylurgops palliatus)对寄主树木的入侵。

1.3 信息素对小蠹虫聚集和种群密度的调控Wood(1982)和Borden(1982;1995)认为小蠹虫在寄主树木上的聚集开始于小蠹虫对寄主树木和小蠹虫信息素的接受,结束于小蠹虫和寄主树木信息素释放的终止。Borden(1982)揭示了黄杉大小蠹入侵危害后信息素对其种群密度的调节机制,并认为小蠹虫在寄主树木韧皮部内的种群密度与信息素分泌和调节有密切关系。Borden(1982;1995),Wood(1982)等均证实了小蠹虫自身合成与分泌的抗聚集信息素(反式马鞭烯醇、endo-brevicomin、exo-brevicomin等)和寄主树木被害后的代谢物质(3, 2-MCH、3, 3-MCH等),通过小蠹虫排泄物或凝脂释放,调节小蠹虫入侵的种群密度,以避免小蠹虫种群密度过高而引发的食物短缺和流行病的发生。但由于各小蠹虫自身分泌信息素种类的差异、寄主树木生理生化代谢的不同、小蠹虫相关微生物的多样性和代谢的差异性等因素,使小蠹虫入侵种群密度的调节机制具有种间的特异性和多样性。

2 小蠹虫信息素的合成与分泌机制Landolt等(1997)认为寄主树木分泌的利它素,能够刺激昆虫神经和保幼激素分泌系统,诱导昆虫信息素的合成和释放。Byers(1982)和Hendry等(1980)研究发现,小蠹虫可以利用寄主树木分泌的萜烯类物质作为信息素或合成信息素的前体,类加州十齿小蠹(I. paraconfusus)利用寄主树木的香叶烯合成小蠹信息素ipsdienol和ipsenol,并在雄性入侵寄主树木修筑坑道时释放出来,并能将寄主树木分泌的α-蒎烯转化为顺式马鞭烯醇。南部松齿小蠹和粗齿小蠹(I. calligraphus),必须在寄主树木分泌的香叶烯已被转化为ipsdienol后,才能表现出引诱活性。黑山大小蠹能够利用寄主树木分泌的α-蒎烯合成反式马鞭烯醇。Borden(1969)、Hughes(1977)和Blight等(1979)认为寄主树木的次生代谢物质能够诱发小蠹虫保幼激素的合成,而保幼激素又反过来刺激脑神经细胞合成信息素。Borden(1982)认为小蠹虫存在自身发育的激素分泌控制系统和独立的微生物控制系统,二者协同作用调节小蠹虫信息素的合成与分泌。Wood(1982)指出韧皮部小蠹和食菌小蠹(如大小蠹属Dendrocyonus、小蠹属Ips和木小蠹属Trypodendron)雌性性信息素的合成明显受到寄主树木挥发性物质的刺激或完全依赖于寄主树木挥发性物质。黄杉大小蠹合成的信息素frontalin,只有在寄主树木次生性物质α-蒎烯的激活作用下才表现出活性。寄主树木分泌的α-cubebene是欧洲榆小蠹(S. multistriatus)信息素Multistriatin和4-methyl-3-heptanol活性的增效剂。

Graham(1967)研究表明小蠹虫内生和外生真菌参与小蠹虫信息素的合成与分泌。Brand等(1976)研究表明,瘤额大小蠹(D. frontalis)贮菌器携带的真菌能将寄主树木分泌的引诱剂(顺式马鞭烯醇和反式马鞭烯醇)转化为抗聚集信息素(马鞭烯酮),而且瘤额大小蠹内生酵母菌的代谢物质可以提高瘤额大小蠹引诱剂frontalin的生物活性。Silverstein(1966)和Borden(1982)揭示出类加州十齿小蠹信息素生物合成和控制系统。

3 信息素对小蠢生态系统和天敌昆虫的影响 3.1 信息素对小蠹生态系统的影响Birch(1975)提出在生态位重叠的小蠹间存在信息素通讯的协调机制,并证实了类加州十齿小蠹与云杉松齿小蠹(I. pini)间信息素的通讯机制。Brown(1970)研究表明,初期性小蠹虫分泌的信息素,(聚集信息素和利它素)常被用于干扰次期性小蠹的定向入侵行为,以保证初期性小蠹虫具有最大的繁殖机会。Birch(1980)揭示了南松立木上多种小蠹虫之间信息素的复杂通讯,瘤额大小蠹和同时入侵的南部松齿小蠹分泌的利它素,能够引诱美东最小齿小蠹和粗齿小蠹的入侵。小蠹种间信息素分泌与接受的复杂性和协调性,使各小蠹虫能够协同入侵寄主树木,并确保各自占据相对稳定的寄主树木营养和生存空间。陈辉(1999)研究表明,秦岭华山松立木上各小蠹虫间具有入侵时序差异和生态位的重叠与分离,这可能也是寄主华山松次生挥发性物质和小蠹虫信息素综合调控的结果。

3.2 信息素对小蠹天敌昆虫的影响在森林生态系统内不仅小蠹虫与寄主树木间和其它小蠹虫间具有复杂的信息素分泌和调控系统,而且小蠹虫分泌的信息素和寄主树木分泌的次生挥发性物质也能引诱天敌昆虫的捕食和寄生,小蠹虫分泌的信息素可以作为天敌昆虫的引诱剂和捕食行为的调节剂。

Vite(1970)研究表明,疑山郭公甲(Thanasimus dubius)对瘤额大小蠹具有完全的生存适应性,并能有效的利用瘤额大小蠹信息素,确保与瘤额大小蠹发育和入侵节奏的一致性。Borden(1982)发现截尾金小蜂(Tomicobia tibialis)能够利用寄主树木和齿小蠹信息素,在小蠹入侵寄主树木前产卵于齿小蠹鞘翅和前胸背板上。Thatcher(1960)发现长足虻(Medetera bistriata)在瘤额大小蠹和美东最小齿小蠹新形成的韧皮部坑道内产卵,以便孵化的幼虫能够进入小蠹坑道内捕食小蠹幼虫1)。Borden(1982)研究表明,长足虻(Medetera aldrichii)能够利用寄主树木和黄杉大小蠹(Dendroctonus pseudotsugae)抗聚集信息素,并滞后于黄杉大小蠹的发育,以便黄杉大小蠹发育出更多的成熟幼虫,从而避免了食物的短缺和提高了营养利用的有效性。

1) Thatcher R C.Bark beetles affecting southern pines:A review of current knowledge.USDA For Serv Occas Pap 180.1960:25

陈辉, 唐明, 叶宏谋, 等. 1999. 秦岭华山松小蠹生态位研究. 林业科学, 35(4): 40-44. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-7488.1999.04.007 |

Amman G D, Lindgren B S. Semiochemicals for management of mountain pine beetle. In: Salom S M, Hobson K R eds. Application of semiochemicals for management of bark beetle infestations: proceedings of an informal conference, Collingdale: Diane Publishing Company, 1998, 14-22

|

Birch M C, Svihra P, Paine T D, et al. 1980. Influence of chemically mediated behavior on host tree colonization by four cohabiting species of Bark Beetles. J Chem Ecol, 6(2): 395-414. DOI:10.1007/BF01402917 |

Birch M C, Wood D L. 1975. Mutual inhibition of the attractant pheromone response by two species of Ips. J Chem Ecol, 1(1): 101-113. |

Blight M M, Wadhams L J, Wenham M J, et al. 1979. Field attraction of Scolytus scolytus to the enantiomers of 4-methyl-3-heptanol, the major component of the aggregation pheromone. J For, 52(1): 83-90. |

Borden J H, Bennett R B. 1969. A continuously recording flight mill for investigating the effects of volatile substances on the flight of tethered insects. J Econ Entomol, 62(4): 782-785. DOI:10.1093/jee/62.4.782 |

Borden J H. Aggregation pheromones. In: Mitton J B, Sturgeon K B eds. Bark Beetles in North American forest. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. 1982, 74-439

|

Borden J H. Behavioral responses of coleoptera to pheromones, allomones and kairomones. In: Shorey H H and Mckelvey J J eds. Chemical control of insect behavior: theory and application. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1977, 169-198

|

Borden J H. 1967. Factors influencing the response of Ips paraconsusus to male attractant. Can Entomol, 99: 1164-1193. DOI:10.4039/Ent991164-11 |

Borden J H. From identifying semiochemicals to developing a suppression tactic: a historical review. In: Salom S M, Hobson K R eds. Application of semiochemicals for management of bark beetle infestations: proceedings of an informal conference. Collingdale: Diane Publishing Company, 1998, 3-10

|

Brand JM, Bracke J W, Britton L N, et al. 1976. Bark beetle pheromones: production of verbenone by a mycangial fungus of D.frontalis. J Chem Ecol, 2(2): 195-199. |

Brown W L Jr, Eisner T E, Whittaker R H. 1970. Allomones and kairomones: transpecific chemical messengers. Bioscience, 20: 21-22. DOI:10.2307/1294753 |

Byers J A. 1982. Male specific conversion of the host plant compound myrcene to the pheromone (+)-ipsdienol in the Bark Beetle D.brevicomis. J Chem Ecol, 8(2): 636-372. |

Dickens J C, Billings R F, Payne T L. 1992. Green leaf volatiles interrupt aggregation pheromone response in Bark Beetles infesting southern pines. Experientia, 48(5): 523-524. DOI:10.1007/BF01928180 |

Ferrell G T. 1971. Host selection by the fir engraver, Scolytus ventralis: preliminary field studies. Can Entomol, 103(12): 1717-1725. DOI:10.4039/Ent1031717-12 |

Graham K. 1968. Anaerobic induction of primary chemical attractancy for ambrosia beetles. Can J Zool, 46: 905-908. DOI:10.1139/z68-127 |

Graham K. 1967. Fungal-insect mutualism in trees and timber. Ann Rev Entomol, 12: 105-126. DOI:10.1146/annurev.en.12.010167.000541 |

Hedden R L, Billings R F. 1977. Seasonal variation in fat content and size of the southern pine beetle in east Texas. Ann Entomol Soc Am, 70(6): 876-880. DOI:10.1093/aesa/70.6.876 |

Hendry L B, Piatek B, Browne L E, et al. 1980. In vivo conversion of a labelled host plant chemical to pheromones of the Bark Beetle Ipsparaconfusus. Nature, 248: 485. |

Hughes P R, Renwick J A A. 1977. Hormonal and host factors stimulating pheromone synthesis in female western pine beetles D. brevicomis. Physiol Entomol, 2(4): 289-292. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-3032.1977.tb00119.x |

Johnson P C, Coster J E. 1978. Probability of attack by southern pine beetle in relation to distance from an attractive host tree. For Sci, 24(4): 574-580. |

Landolt P J, Phillips T W. 1997. Host plant influences on sex pheromone behavior of phytophagous insects. Ann Rev Entomol, 42: 371-391. DOI:10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.371 |

Paine T D, Bertram S L. Management potential of semiochemicals for protection of trees from western pine beetle. In: Salom S M, Hobson K R eds. Application of semiochemicals for management of bark beetle infestations: proceedings of an informal conference. Collingdale: Diane Publishing Company, 1998, 11-13

|

Rudinsky J A. 1966. Scolytid Beetles associated with Douglas-fir: response to terpenes. Science, 152: 218-219. DOI:10.1126/science.152.3719.218 |

Salom S M, Hobson K R. Introductory remarks: informal conference on application of semiochemicals for management of bark beetle infestations. In: Salom S M, Hobson K R eds. Application of semiochemicals for management of Bark Beetle infestations: proceedings of an informal conference, Collingdale: Diane Publishing Company, 1998, 1-2

|

Schroeder L M. 1992. Olfactory recognition of nonhosts aspen and birch by conifer Bark Beetles Tomicus piniperda and Hylurgops palliatus. J Chem Ecol, 18(9): 1583-1593. DOI:10.1007/BF00993231 |

Silverstein R M, Rodin J O, Wood D L. 1966. Sex attractants in frass produced by male Ips confusus in ponderosae pine. Science, 154: 509-510. |

Visser J H. 1986. Host odor perception in phytophagous insects. Ann Rev Entomol, 31: 121-144. DOI:10.1146/annurev.en.31.010186.001005 |

Vite J P, Williamson D L. 1970. Thanasimus dubius: prey perception. J Insect Physiol, 16(2): 233-239. DOI:10.1016/0022-1910(70)90165-4 |

Wood D L. 1982. The role of pheromones, kairomones, and allomones in the host selection and colonization behavior of bark beetles. Ann Rev Entomol, 27: 411-446. DOI:10.1146/annurev.en.27.010182.002211 |

2003, Vol. 39

2003, Vol. 39