文章信息

- 张小全, 吴可红.

- Zhang Xiaoquan, Wu Kehong.

- 森林细根生产和周转研究

- FINE-ROOT PRODUCTION AND TURNOVER FOR FOREST ECOSYSTEMS

- 林业科学, 2001, 37(3): 126-138.

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2001, 37(3): 126-138.

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:1999-12-02

-

作者相关文章

2. Institute of Forest Botany, University of Goettingen, Buesgenweg 2, Goettingen, D-37077, Germany

2. Institute of Forest Botany, University of Goettingen, Buesgenweg 2, Goettingen, D-37077, Germany

细根通常是指直径小于2~5mm的根。细根虽然仅占林分根系总生物量的3%~30% (Vogt et al., 1996), 但它具有巨大的吸收表面积、生理活性强, 是树木水分和养分吸收的主要器官。同时多数树种细根有菌根浸染, 大大增加了吸收表面积。细根生长和周转迅速, 对树木碳分配和养分循环起着十分重要的作用。细根生命周期短至数天, 最长也仅几年(Lawson, 1995)。通过细根周转进入土壤的有机物[地下凋落量]是地上凋落量的一至数倍(Arthur et al., 1992; Berish et al., 1988; Joslin et al., 1987; Kummerow, 1981; Vogt et al., 1986b)。如果忽略细根的生产、死亡和分解, 土壤有机物质和养分元素的周转将被低估20%~80% (Vogt et al., 1986b)。同时细根动态对环境变化具有重要指示作用, 可反映树木或生态系统水平的健康状况(Vogt et al., 1993;Bloomfield et al., 1996)。

在过去近40年中, 植物细根研究取得了长足的发展, 从1968年至今, 已有十多次大型国际根系学术研讨会。讨论的主要内容有根系分类、根系结构、根系解剖和生理、根的结构和功能、树木根系及其菌根、根系研究方法、根系生长与环境、根系与碳平衡、全球变化与根系等。近20年来, 国外对树木细根生长、周转和分解及其对土壤养分、树木营养和生态系统碳平衡的影响的研究日益受到研究人员的重视, 取得了丰硕的研究成果。国内也开展了少量研究(廖利平等, 1995; 1999;单建平等, 1993;温达志等, 1999;李凌浩等, 1998)。单建平等(1992)简要介绍了国外树木细根的研究动态; 黄建辉等(1999)对细根生物量测定方法进行了介绍; 张小全等(2000)介绍了目前国外普遍采用的树木细根生态学研究方法及其优缺点、适用性以及不同方法的研究比较。本文对近期国内外在树木细根生态学方面的研究结果进行分析总结, 包括细根生物量及分布、细根生产、周转及其对土壤碳和养分的影响等, 以期为我国树木细根生态学研究提供参考。

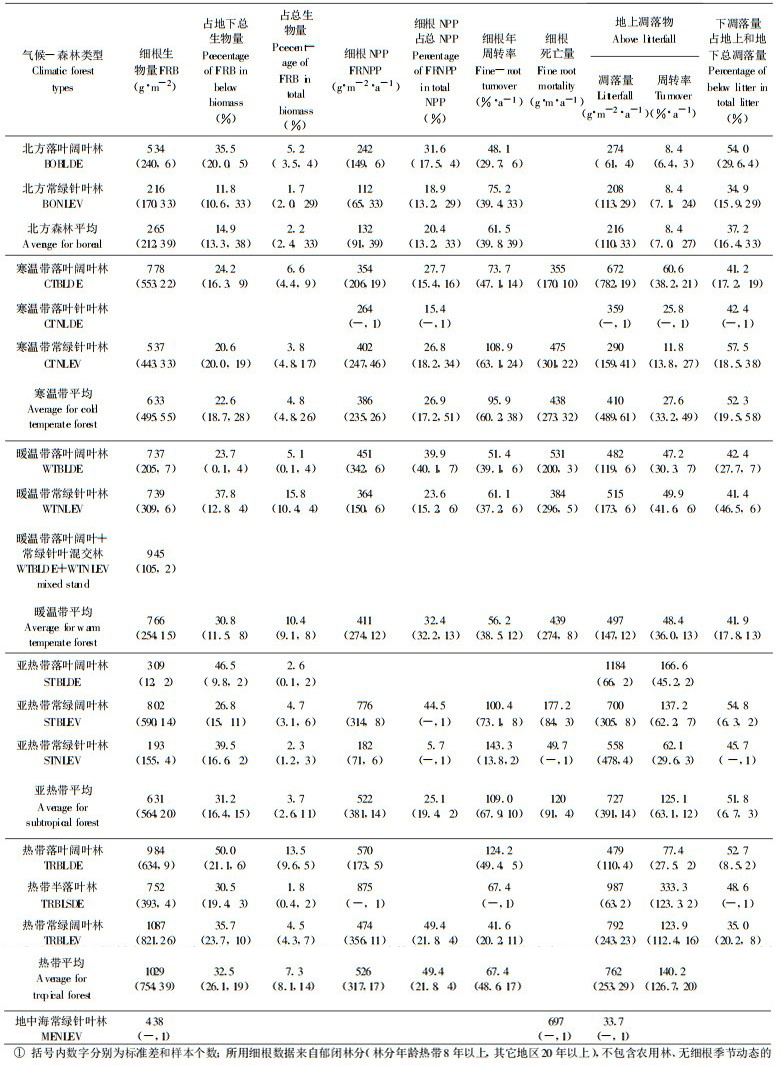

1 森林细根生物量及其分布 1.1 细根生物量根据全世界不同森林生态系统100多个细根生物量研究资料, 细根(直径 < 2~5mm)生物量变化在46~2805g·m-2之间(样本数n:169), 大部分(n:125)在100~1000 g·m-2之间。细根生物量分别占地下部分总生物量和林分总生物量的1.1%~74.7% (n:105)和0.1%~32.2% (n:93), 大多数为3%~30% (n:71)和0.5%~10% (n:79) (Vogt et al., 1996;Bauhus et al., 1996; Ruess et al., 1996; Steele et al., 1997; Sundarapadian et al., 1996;廖利平等, 1995;单建平等, 1993;温达志等, 1999;李凌浩等, 1998)。实际比例可能更低, 因为许多研究测定的粗根生物量数据并不包含粗大的主根和侧根。不同气候、森林类型、土壤类型和立地质量, 细根生物量及其在地下部分和总生物量中所占比例不同, 且无明显变化趋势, 主要由于细根生物量在各类型内部的变异性大, 平均值未能反映影响细根生物量变化的因子(Vogt et al., 1996), 同时不同研究采用的细根分级标准不一, 从 < 1mm到 < 5mm不等, 且一些类型样本数少, 有的研究未区分活细根和死细根, 细根生物量中包含死细根生物量, 这些均降低了可比性。但分析发现, 在大多数细根生物量高的土壤中, Al和Fe含量较高(Vogt et al., 1996)。按不同典型气候森林类型平均(表 1), 细根生物量在216 g·m-2 (北方常绿针叶林)和1087 g·m-2 (热带常绿阔叶林)之间, 细根生物量占地下部分生物量和总生物量的比例分别为11.8%~50%和1.7%~15.8%。尽管变异较大, 但除亚热带落叶阔叶林和常绿针叶林较低外(可能与样本数太少有关), 从北方森林到寒温带、暖温带到热带森林, 细根生物量呈增加趋势。尽管热带气温较高, 细根呼吸消耗大(Sprugel et al., 1994), 且大部分热带地区土壤有效养分贫乏(Vitousek et al., 1986), 但由于热带森林较高的有机质积累速率(Vogt et al., 1995b), 保证了森林生长的需要, 使之维持较高的细根生物量。同一气候带不同森林类型比较, 落叶阔叶林平均细根生物量大于常绿针叶林, 但低于常绿阔叶林; 除暖温带外, 落叶阔叶林细根生物量所占比例均大于常绿针叶林(表 1)。

|

|

细根生物量通常随年龄增加而增加, 在一定时期达到最大值, 随后逐渐下降, 并趋于稳定(Chaturvedi et al., 1982;Vogt et al., 1983a;李凌浩, 1998)。在采伐初期细根生物量增加最快(Berish et al., 1988;Raich, 1980), 主要与采伐迹地上灌木和草本迅速生长或林分萌芽有关。细根生物量通常在林分郁闭后趋于稳定(Finér et al., 1997;Ruark et al., 1987;Vogt et al., 1983a; 1983b)。但在贫瘠立地上, 细根生物量随年龄增长的增加要缓慢得多, 并在郁闭后维持较高的生物量(Uhl et al., 1982, Vogt et al., 1983a); 而在良好立地上, 细根生物量迅速增加并在郁闭后调整到较低的水平上(Vogt et al., 1983a)。Grier (1981)和Persson (1983)分别测定发现, 冷杉(Abies amabilis)从23~180a和欧洲赤松(Pinus sylvestris)从20~120a, 细根生物量增加, 可能与立地条件较差、有效养分大量消耗有关。研究还发现, 随林分年龄增加细根长度降低, 直径增大(Finér et al., 1997), 也可能与有效养分下降有关, 因为肥沃立地通常生长较细的根(Persson, 1980b)。

细根生物量或细根量具有明显的季节节律。在热带多为单峰型, 主要与土壤水分有关, 生物量高峰和低峰分别出现在雨季和旱季, 且细根直径越小, 季节变化越明显(Kavanagh et al., 1992;Khiewtam et al., 1993;Sundarapandian et al., 1996)。在温带, 部分研究为单峰型, 峰值出现在春季(如Burke et al., 1994;Joslin et al., 1987)或夏秋季(单建平等, 1993;Hendrick et al., 1992a;1993a;McClaugherty et al., 1982;Rytter et al., 1996);许多测定为双峰型, 峰值分别出现在春季和秋季, 主要与土壤水分状况有关(Harris et al., 1977;Teskey et al., 1981)。在亚热带, 杉木和火力楠细根生物量与地上部生长节律一致, 出现两次生物量高峰(廖利平等, 1995), 而鼎湖山季风常绿阔叶林和针阔混交林细根生物量为单峰型, 峰值出现在7月份(温志达等, 1999)。盛夏根系停止生长通常与环境胁迫有关, 如较高的温度和干旱(Harris et al., 1977;Santantonio et al., 1985;Singh et al., 1985;Teskey et al., 1981;Waring et al., 1985)或树木将更多的光合产物用于茎的生长(Dewar et al., 1994, Grier et al., 1981)。

混交林或农林混作可提高细根生物量(Fredericksen et al., 1995;Lehmann et al., 1998), 主要与不同植物对土壤空间的补充利用有关(Lehmann et al., 1998), 同时土壤和根际物理、化学性质得到改善, 如增加土壤N有效性(Haggar et al., 1993;Lehmann et al., 1997), 改善土壤孔隙度、渗透性等(Torquebiau et al., 1996)。但是不同混交树种细根生物量与其地上部分所占空间并不一定成正比(Büttner et al., 1994)。

1.2 细根垂直分布树木根系的垂直分布与树种、年龄、土壤水分、养分和物理性质(通气、机械阻力等)、地下水位等有关。树木或林分大部分根系位于50cm土层以上, 且多集中于枯落物层和10cm以上矿质土壤表层(Burke et al., 1994;Büttner et al., 1994;Finér et al., 1997;Denich, 1998;Hermann, 1977;Hahn et al., 1998;Liu et al., 1997;Majdi et al., 1993;Persson, 1978;1979;Steele et al., 1997;Fischer et al., 1998;Rytter et al., 1996;温达志等, 1999;李凌浩等, 1998)。细根生物量随深度增加呈指数递减(Lawson, 1995)。Jackson et al. (1996)综合分析大量研究数据发现, 北方森林根系分布最浅, 而温带针叶林最深, 它们在表层30cm内的根系分别占80%~90%和50%。一些树种细根垂直变化不明显或中下部土层分布有较多的根系(Fischer et al., 1998;Jonsson et al., 1988;Dhyani et al., 1990;Toky et al., 1992)。土壤温度从地表向下迅速下降是细根集中于表层的重要原因(Tryon et al., 1983;Steele et al., 1997)。提高土壤温度不但使细根生物量增加, 而且使细根趋于深土层分布(Ruijter et al., 1996)。表层丰富的养分条件也有利于细根生长。

早期演替阶段林分根系分布较深, 而后期较浅(Grier et al., 1981);对同一树种年龄较大的林分, 细根趋向于表层(Berish, 1982;Grier et al., 1981;Jorgensen et al., 1980);主要与幼龄或早期演替阶段腐殖层薄、土壤贫瘠, 随着林分的发展, 大量凋落物在表层积累有关。在贫瘠土壤上生长的高生产力林分, 表层表现出细根集结的特征(Klinge, 1973;Huttel,1975)。Jorgensen et al. (1980)计算表明, 16年生火炬松(Pinus taeda L.)林分所需34%的氮来源于枯落物层(Forest floor), 而30~40年生林分则达85%。但在良好立地上, 随年龄增加细根表层化并不显著(Person, 1983;Vogt et al., 1983a)。除立地条件外, 不同发育阶段林分细根垂直分布的变化还与林分内不同植物对竞争的适应有关, 以最大限度地降低对土壤水分和养分的竞争, 达到资源的合理分配与利用(Strong et al., 1983;Finér et al., 1997;Vogt et al., 1983a)。

细根垂直分布还与树木耐旱性有关, 受干旱胁迫症状最明显的树种在深土层的细根生物量最小(Fischer et al., 1998)。干旱胁迫使细根向深土层发展, 深土层细根比例增加(Persson et al., 1995)。在混交林中, 为适应对水分和养分的竞争, 不但不同种类细根的空间分布不同, 而且在生长、养分和水分吸收的时间上也有差异(Davis et al., 1986;Büttner et al., 1994)。

2 森林细根生产根据100多个森林生态系统的研究结果, 细根年净生产量20~1317g·m-2·a-1 (n:148), 占林分总净初级生产量的3%~84% (n:102), 大部分在10%~60% (n:90)。不同气候、森林、土壤类型变化较大, 根系生物量与分配到地下部分的生产量无明显的相关性, 但具有较高的细根生产力并将较高比例的碳分配到细根的生态系统, 均具有较低的细根生物量比率(Vogt et al., 1996)。若按气候森林类型平均(表 1), 细根生产量呈现与生物量相似的变化趋势, 即从北方森林到温带、亚热带至热带, 细根生产量呈增加趋势。一些研究表明, 针叶林分配较大比例的光合产物到细根生产(如Ruess et al., 1996;Vogt et al., 1986b), 但我们的分析结果相反, 即在同一气候带内针叶林细根生产在总净初级生产中的比例却小于阔叶林(常绿和落叶) (表 1)。与细根生物量相似, 在将较多的净初级生产分配到细根的生态系统中, 植物生长均受到较高的土壤Al和Fe含量的限制, 较高的细根生产可能与避免Al毒害的机制有关(Vogt et al., 1996)。具有较高细根分配比率的热带森林生态系统常出现表层根垫(root mat)和背地性根的特征(Benzing, 1991), 且有效养分均较低(Sanford, 1987)。在不同生长发育阶段, 细根生产量不同, 如Finér et al., (1997)对火烧后48~232年混交林以及Persson (1983)对20~120年欧洲赤松林的研究均表明, 细根生产随年龄增加而降低; 李凌浩等(1998)对17~76年生甜槠林研究表明, 细根生产量在58a时最大; 而冷杉(Abies amabilis)从23年到180年细根生产增加(Grier et al., 1981), 后者可能与土壤肥力下降有关。

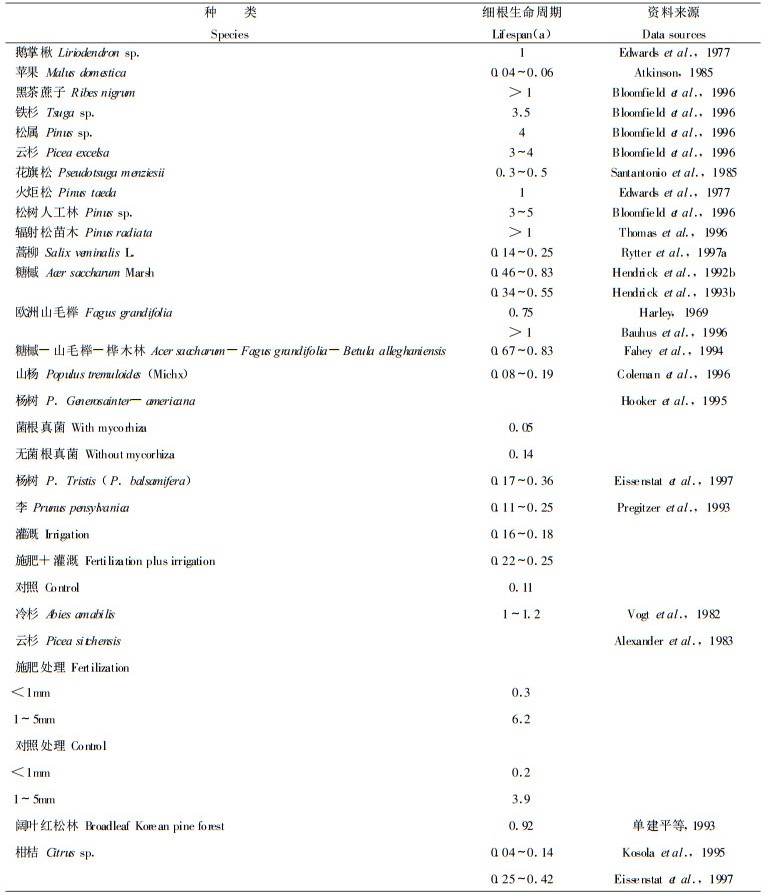

3 细根周转 3.1 细根生命周期树木主根和侧根生命期通常与树木本身生命周期相同(Vogt et al., 1991a), 对中小根生命期的研究较少。树木细根生命周期短至数天或几周(Atkinson, 1985;Black et al., 1998;Coleman et al., 1996;Fabiao et al., 1985;Hooker et al., 1995;Krauss et al., 1994;Reid et al., 1993), 长至数月(单建平等, 1993;Fahey et al., 1994;Hendrick et al., 1992b)或1到几年(Alexander et al., 1983;Bauhus et al., 1996;Edwards et al., 1977;Lyr et al., 1967;Kolesnikov, 1971;Thomas et al., 1996;Vogt et al., 1982) (表 2)。如Black et al. (1998)观测到40%的欧洲甜樱桃(Prunus avium L.)细根生命周期期短于14天, 不到8%的细根超过63天, 北美云杉(Picea sitchensis Bong.)、杨树(Populus×canadensis cv. Beaupre)和欧亚槭(Acer pseudoplatanus L.)分别有54%、36%和24%的细根生命周期超过63天。而Hendrick et al. (1992b)测定的糖槭(Acer saccharum Marsh)细根生命周期长达5.5~10个月。Thomas et al. (1996)观察到辐射松(Pinus radiata)苗木细根在1年内无死亡现象。有的早期研究更长, 从2年(Lyr et al., 1967)至12年(Kolesnikov, 1971)。除与树木种类有关外, 还受树木体内碳源-碳汇分配关系的控制, 与3个因素有关(Lawson, 1995) : (1)地上部分提供的净碳量; (2)根系生长和维持所需的碳量;和(3)根系生长的微环境因子, 包括土壤养分、水分、养分有效性及土壤温度、有毒元素、菌根和其它土壤生物等。前两个因素是在树木整体或生态系统水平上调节根系周转, 而微环境因素则是在单个根水平上影响细根生命周期(Bloomfield et al., 1996)。在贫瘠立地上, 植物将分配更多的光合产物用于细根生产, 周转加快, 但细根的生命周期缩短, 而肥沃立地有利于延长细根生命周期(Alexander et al., 1983;Axelsson, 1981;Berntson et al, 1995;Cannell, 1985;Gower et al., 1992;Keyes et al., 1981;Pregitzer et al., 1993)。但也有研究表明, 低养分环境有利于延长细根生命周期, 而肥沃土壤则会缩短细根生命周期(如Aber et al., 1985;Grime et al., 1991;Nadelhoffer et al., 1985;Pregitzer et al., 1995)。Hendrick et al. (1996)认为细根生命周期与土壤养分有效性可能呈正相关, 也可能呈负相关, 取决于植物种类、器官或整个植物碳平衡、有效养分在土壤中分布的空间异质性等。在干旱胁迫下, 可产生生命周期长的细根(Eissenstat et al., 1997)。较高的土壤温度可增加细根生产, 促进细根周转, 细根生命周期缩短(Steele et al., 1997;Hendrick et al., 1993b)。共生微生物在增加细根生命周期方面起着重要作用(Bloomfield et al., 1996), 特别是多数树种具有的菌根真菌, 能增加细根生命周期(Harley, 1969;Harley et al., 1983;Vogt et al., 1982)。菌根真菌延长细根生命周期与菌根菌通过分泌化学物质和物理阻隔以保护细根不受病菌的侵害有关, 菌根真菌的存在还能提高植物对有毒物质的抗性, 从而延长细根生命周期(Bloomfield et al., 1996)。病源微生物也是影响细根生命期的重要因子之一, 如根腐真菌可直接伤害根组织和引起碳水化合物贮存的损失, 从而促进根衰亡, 缩短根生命周期(Bloomfield et al., 1996)。

|

|

森林生态系统细根年周转率(细根生产/活细根生物量)因不同气候和森林类型而异, 变化较大(表 1), 年周转率4.3%~273.2% (n=117)。亚热带森林周转率较高, 这也是前述亚热带细根生物量较低的原因。而细根生物量和生产量均较高的热带常绿阔叶林周转率并不高。一般认为, 在温暖气候条件下, 细根的周转要快得多, 特别是在潮湿热带森林中, 细根周转率尤高(Vogt et al., 1986a), 甚至每年细根可能会发生数次周转(Lawson, 1995)。如Sanford (1985)估计在表层10cm的细根月周转率达25%, 年生产量达15.4t/hm2。相同气候带内阔叶林细根周转率低于针叶林, 是针叶林维持较低细根生物量的原因(表 1)。由于维持高的细根生物量需要消耗大量的碳, 因此保持较高的细根周转率可能是植物降低能量消耗的一种适应策略(Fogel, 1983)。近几年的研究结果表明, 细根周转率可能更高。如Schoettle et al. (1994)综合世界各地松树细根研究结果表明, 细根周转率在0.2~5.0 a-1之间; Rytter et al. (1997a)计算的柳树人工林细根周转率高达4.9~5.8 a-1。

细根生产和周转还具有明显的季节性。如在温带针叶林中, 细根生长峰值出现在春季或夏季, 细根死亡在冬季最低, 夏季或秋季最高, 取决于树种和当地气候条件(温度) (单建平等, 1993;Steele et al., 1997)。温带阔叶林细根生产峰值出现在春季(Hendrick et al., 1993a;Joslin et al., 1987;McClaugherty et al., 1982), 也有的出现在夏季(Burke et al., 1994), 细根死亡高峰出现在秋季(Hendrick et al., 1993a)。细根周转的季节变化可能与土壤温度有关, 随温度的上升, 周转加快(Marshall et al., 1985;Burke et al., 1994)。Rytter et al.(1997a, 1997b)发现柳树(Salix veminalis L.)细根生长和死亡无明显的季节变化特征, 但生长和死亡密切相关, 生长峰值总伴随着几星期后的一个死亡峰值。

混交和农林混作不但可增加细根生物量, 还可提高细根生产和周转(Frederichsen et al., 1995;Lehmann et al., 1998;廖利平等, 1995)。如Lehmann et al. (1998)报道, 农林混作系统细根生产量是树木和作物分作的约一倍。土壤资源的更充分利用以及土壤理化性质的变化是促进细根生产的原因。

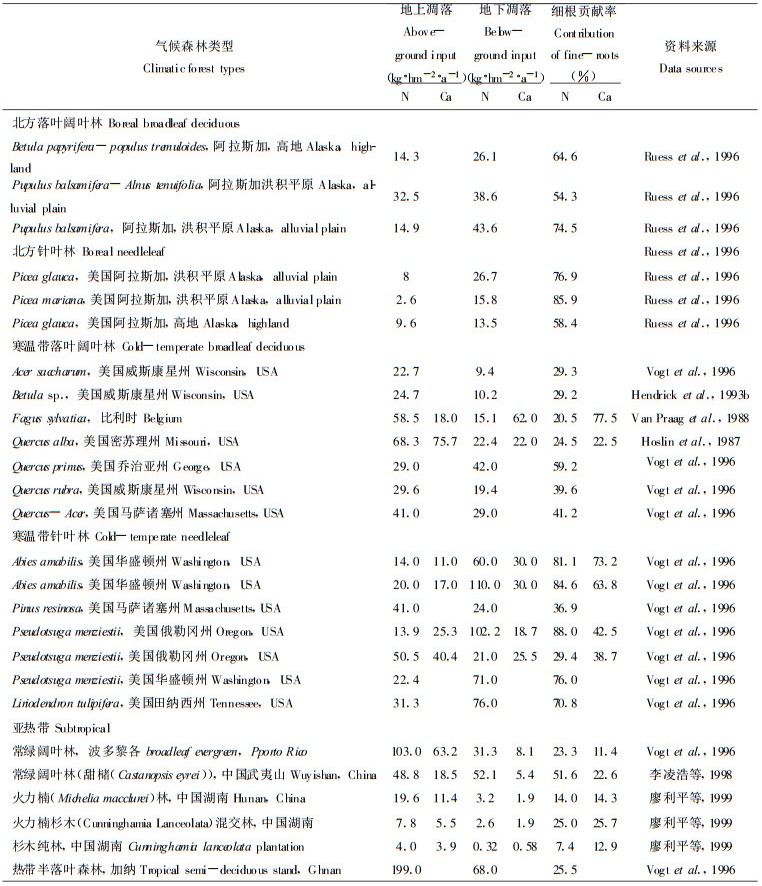

4 细根生产和周转对土壤碳和养分的影响细根周转形成的地下凋落物是土壤碳和养分的重要来源。地下凋落物占总输入(细根生产和地上枯落物输入)的6.2%~88.7% (n: 114), 平均50%左右。不同气候带无明显变化趋势。在寒温带常绿针叶林细根的贡献大于落叶阔叶林(平均值), 而北方森林则相反; 在暖温带二者相近; 热带和亚热带资料少(表 1)。在温带, 细根死亡进入土壤的有机碳占总输入量的14%~86.8% (n:40), 大多数在40% (n:30)以上。Vogt et al. (1986b)分析表明, 细根周转对土壤N和C的贡献比枯落物大18%~58%, 如果忽略细根的生产、死亡和分解, 土壤有机物质和营养元素的周转将被低估20%~80%。大量测定结果表明(表 3), 细根生产和周转向土壤输入的N和Ca占地上和地下总输入量的相当大比例, 其中以北方森林和寒温带常绿针叶林较大, 通过细根输入到土壤的N量多数大于枯落物输入。细根死亡分解对土壤其它养分元素(P、K、Mg)的贡献率也较大, 甚至接近或大于地上枯落物的作用(李凌浩等, 1998;廖利平等, 1999)。

|

|

但是细根是否如叶片一样在衰亡时存在养分转移, 则有不同的结论。有的研究表明不存在明显的养分转移(Nambiar, 1987);另一些研究得出相反的结论(Ritz et al., 1985;Vogt et al., 1995b), 且受菌根侵染的细根转运养分的速度快得多(Ritz et al., 1985)。不同养分元素转运方向也不同, Al转入细根, 而P、K、Ca、Mg、Mn、Zn、Cu则转出细根, Fe同时存在转入和转出(Vogt et al., 1995b)。

5 细根分解对枯落物和细根的分解速率的比较, 目前很难做出定论。有些树木细根的分解速率比叶片快, 另一些则比叶片慢(Vogt et al., 1991b)。与叶片相比, 细根较高的结构性木质纤维素或软木脂和铝含量可显著降低分解速率(Aber et al., 1992; Bloomfield et al., 1993)。不少研究表明, 树种细根木质素含量高于叶片(Berg et al., 1981;McClaughert et al., 1984;Bloomfield et al., 1993;Bloomfield, 1993;Bloomfield et al., 1996), 但Berg et al. (1981)发现, < 1mm细根木质素含量明显高于更粗的根。正在分解的细根中均有Ca的积累(Lawson 1995)。由于对细根分解速率的测定方法不同(网袋法、壕沟法、微根管法、平衡法等), 结果相差较大。网袋法通常会低估分解速率(Santantonio et al., 1985;Lyr et al., 1967;Vogt et al., 1991b)。壕沟法估计的年分解率虽然大于网袋法, 但仍可能低估细根分解速率, 因为木质化活细根通常有大量的碳水化合物贮藏, 在用壕沟法切断后, 这些贮藏物质不仅能维持细根的外观, 而且能推迟分解生物(如微生物)对细根的分解作用; 而对正常死亡的细根, 由于在死亡前贮藏物质发生转运, 因此不存在这种现象(Vogt et al., 1991b)。用微根管观察表明, 细根的分解要比预想的要快得多(Hendrick et al., 1992a)。

6 展望细根生产和周转在森林生态系统能量流动和物质循环中的作用已为学术界广泛认同, 在国外已开展了大量的研究, 而在国内尚未引起充分重视。结合国内外的研究动态和我国实际, 我国需在以下几个方面展开研究:

(1) 主要森林生态系统细根生产和周转及其在能流和物流中的作用。我国地域广阔, 地形复杂, 气候多样, 孕育了丰富而独特的森林生态系统类型, 对不同气候带典型森林生态系统细根生产和周转进行研究, 对于揭示森林生态系统的能量流动和物质循环具有重要意义。国外的研究主要集中在北方森林、寒温带和热带森林生态系统, 而对暖温带和亚热带森林生态系统研究较少。我国在这两个气候带具有丰富的森林生态系统类型, 在这一区域开展研究, 对弥补国外研究的空缺, 还具有特殊的意义。

(2) 人工林生态系统细根生产与周转。近几十年来, 特别是改革开放以来的生态林业工程和用材林基地建设, 形成了大面积的人工林。一些树种由于大面积的人工纯林和和连栽, 已引起严重的地力退化和产量下降, 如杉木、桉树等。对人工林生态系统细根生产和周转进行研究, 对于揭示人工林地力退化机理及维护措施具有重要意义。

(3) 树木细根生产和周转与土壤水分、养分以及其它土壤理化性质(土壤pH值、质地、孔隙度、容重、温度等)密切相关, 对这些关系进行研究, 可揭示树木在劣质立地条件下的响应和适应策略, 并为土壤改良措施提供科学依据。

(4) 与全球变化有关的森林细根研究。包括细根在森林生态系统碳平衡中的作用(细根生产、周转、呼吸、分解等)、大气CO2浓度增加和全球变暖对细根生产和周转的影响等。

(5) 环境污染对细根生产和周转的影响。包括酸沉降、大气O3浓度以及土壤重金属离子等的影响。

(6) 不同细根测定方法的比较研究。目前有多种树木细根研究方法, 如根钻法、微根管法、生长袋法等直接方法和N平衡法、C通量法等间接方法, 每种方法都有其自身的优缺点, 适于不同的研究对象和目的, 不同研究人员采用的方法也不同。因此为使研究结果便于与其它的研究结果比较, 建议采用多种方法并行。

黄建辉, 韩兴国, 陈灵芝. 1999. 森林生态系统根系生物量研究进展. 生态学报, 19(2): 270-277. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-0933.1999.02.021 |

李凌浩, 林鹏, 邢雪荣. 1998. 武夷山甜槠林细根生物量和生长量研究. 应用生态学报, 9(4): 337-340. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-9332.1998.04.001 |

廖利平, 陈楚莹, 张家武, 等. 1995. 杉木、火力楠纯林及混交林细根周转的研究. 应用生态学报, 6(1): 7-10. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-9332.1995.01.005 |

廖利平, 杨跃军, 汪思龙, 高洪. 1999. 杉木、火力楠纯林及其混交林细根分布、分解与养分归还. 生态学报, 19(3): 342-346. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-0933.1999.03.009 |

单建平, 陶大立, 王淼, 赵士洞. 1993. 长白山阔叶红松林细根动态. 应用生态学报, 4(3): 241-245. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-9332.1993.03.008 |

单建平, 陶大立. 1992. 国外对树木细根的研究动态. 生态学杂志, 11(4): 46-49. |

温志达, 魏平, 孔国辉, 叶万辉. 1999. 鼎湖山南亚热带森林细根生产力与周转. 植物生态学报, 23(4): 361-369. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1005-264X.1999.04.009 |

张小全, 吴可红, Murach D. 2000. 树木细根生产与周转研究方法评述. 生态学报, 20(5): 875-883. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-0933.2000.05.026 |

Aber J D, Mellilo J M, Nadelhoffer K J. 1985. Fine root turnover in forest ecosystems in relation to quantity and form of nitrogen availability :a comparison of two methods. Oecologia, 66: 317-321. DOI:10.1007/BF00378292 |

Aber J D, Mellilo J M. 1992. Terrestrial ecosystems. Saunders College Publishing, Philadelphia, PA. |

Alexander I J, Fairley R I. 1983. Effects of N fertilization on populations of fine roots and mycorrhizae in spruce humus. Plant and Soil, 71: 49-53. DOI:10.1007/BF02182640 |

Arthur M A, Fahey T J. 1992. Biomass and nutrients in an Engelmann spruce subalpine fir forest in north central Colorado:pool, annual production and internal cycling.Can. J.For.Res, 22: 315-325. |

Atkinson D.Spatial and temporal aspects of root distribution as indicated by the use of a root observation laboratory.In: Fitter A H, Atkinson D, Read DJ et al.(eds), Ecological Interactions.Blackwell Scientific Publications, Boston, 1985: 43~65

|

Axelsson B. 1981. Site differences in yield-differences in biological production or in redistribution of carbon within trees.Sweden Univ.of Agr.Science, Dept. Ecology and Environmental Res.Rep 79. |

Bauhus J, Bartsch N. 1996. Fine-root growth in beech (Fagus sylvatica)forest gaps. Can.J.For.Res, 26: 2153-5159. DOI:10.1139/x26-244 |

Benzing D H.Aerial roots and their environments.In: Wiasel Y, Eshel A, Kafkafi U (eds.), Plant Roots: the Hidden Half.Marcel Dekker, Inc.NewYork, USA, 1991: 867~886

|

Berg B, Staaf H. 1981. Chemical composition of main plant litter components at Ivantjarnsheden-data from the decomposition studies. Swedish Coniferous Forest Project, Internal Report, 104: 1-17. |

Berish C W. 1982. Root biomass and surface area in three successional tropical forests. Can.J.For.Res, 12: 699-704. DOI:10.1139/x82-104 |

Berish C W, Ewel J J. 1988. Root development in simple and complex tropical successional ecosystems. Plant and Soil, 106: 73-84. DOI:10.1007/BF02371197 |

Berntson G M, Farnsworth E J, Bazzaz F A. 1995. Allocation with and between organs and the dynamics of root length changes in two birch species. Oecologia, 101: 439-447. DOI:10.1007/BF00329422 |

Black K E, Harbron C G, Franklin M, et al. 1998. Differences in root longevity of some tree species. Tree Physiology, 18: 259-264. DOI:10.1093/treephys/18.4.259 |

Bloomfield J.Nutrient dynamics and the influence of substrate quality on the decomposition of leaves and fine roots of selected tree species in a lower montane tropical rain forest in Puerto Rico.Ph.D.dissertation, Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Yale Univ., New Haven, CT, 1993

|

Bloomfield J, Vogt K A, Vogt D J. 1993. Decay rate and substrate quality of fine roots and foliage of two tropical tree species in the Luquillo experimental forest, Puerto Rico. Plant and Soil, 150: 233-245. DOI:10.1007/BF00013020 |

Bloomfield J, Vogt K A, Wargo P M.Tree root turnover and senescence.In: Wiasel Y, Eshel A, Kafkafi U (eds.), Plant Roots: The Hidden Half(second edition, revised and expanded).M arcel Dekker, Inc., New York.1996, 363~381

|

Bǜttner V, Leuschner C. 1994. Spatial and temporal patterns of fine root abundance in a mixed oak-beech forest. For.Ecol.Manage, 70: 11-21. DOI:10.1016/0378-1127(94)90071-X |

Burke M K, Raynal D J. 1994. Fine root growth phenology, production, and turnover in a northern hardwood forest ecosystems. Plant and Soil, 162: 135-146. DOI:10.1007/BF01416099 |

Cannell M G R.Dry matter partitioning in tree crops, In: Cannell M G R, Jackson J E (eds.), Attributes of Trees as Crop Plants.Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, Edinburgh, 1985, 160~193

|

Chaturvedi O P, Singh J S. 1982. Total biomass and biomass production of Pinus roxburgii trees growing in all-aged natural forests, Can. J.For.Res, 12: 632-640. |

Coleman M D, Dickson R E, Isebrands J G, et al. 1996. Root growth and physiology of potted and field-grown trembling aspen exposed to tropospheric ozone. Tree Physiology, 16: 145-152. DOI:10.1093/treephys/16.1-2.145 |

Davis S D, Mooney H A. 1986. Water use patterns of four co -occurring chaparral shrubs. Oecologia, 70: 172-177. DOI:10.1007/BF00379236 |

Dewar R C, Ludlow A R, Dougherty P M. 1994. Environmental influences on carbon allocation in pines. Ecol.Bull, 43: 92-101. |

Dhyani S K, Narain P, Singh R K. 1990. Studies on root distribution of five multipurpose tree species in Doon Valley. India Agroforestry Systems, 12: 149-161. DOI:10.1007/BF00123470 |

Denich M, Sommer R, Vlek P L G.Soil carbon stocks in small-holder land-use systems of the Northeast of Para state, Brail.Proceedings of the Third SHIFT -Workshop Manaus, March 15~19, 1998, Hans-Hermann Wulff GKSS -Forschungszentrum Geesthacht GmbH, 1998, 137~140

|

Edmonds R L. 1980. Litter decomposition and nutrient release in Douglas-fir, red alder, western hemlock and Pacific silver fir ecosystems in western Washington Can.. J.For.Res, 10: 327-337. |

Edwards N T, Harris W F. 1977. Carbon cycling in a mixed deciduous forest floor. Ecology, 58: 431-437. DOI:10.2307/1935618 |

Eissenstat D M, Yanai R D. 1997. The ecology of root lifespan. Adv.Ecol.Res, 27: 1-60. DOI:10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60005-7 |

Fabiao A, Persson H, Steen E. 1985. Growth dynamics of superficial roots in Portuguese plantations of Eucalyptus globulus Labill.studied with a mesh bag technique. Plant and Soil, 83: 233-242. DOI:10.1007/BF02184295 |

Fahey T J, Hughes J W. 1994. Fine root dynamics in a northern hardwood forest ecosystem, Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, NH. J.Ecol, 82: 533-548. DOI:10.2307/2261262 |

Finér L, Messier C, De Grandpré L. 1997. Fine-root dynamics in mixed boreal conifer-broad-leafed forest stands at different successional stages after fire.Can. J.For.Res, 27: 304-314. |

Fischer S, Brienza S Jr., Vielhauer K et al.Root distribution in enriched fallow vegetations in NE Amazonia, Brazil.Proceedings of the Third SHIFT-Workshop Manaus, March 15~19, 1998, Hans-Hermann Wulff GKSS-Forschungszentrum Geesthacht GmbH.181~184

|

Fogel R. 1983. Root Turnover and productivity of coniferous forests. Plant and Soil, 71: 75-85. DOI:10.1007/BF02182643 |

Fredericksen T S, Zedaker S M. 1995. Fine root biomass, distribution and production in young pine-hardwood stands. New Forests, 10: 99-110. |

Gower S T, Vogt K A, Grier C C. 1992. Carbon dynamics of Rocky Mountain Douglas-fir:influence of water and nutrient availability. Monogr., 62: 43-65. DOI:10.2307/2937170 |

Grier C C, Vogt K A, KeyesM R, et al. 1981. Biomass distribution and above -and below -ground production in young and mature Abies amabilis zone ecosystems of the Washington Cascades, Can. J.For.Res, 11: 155-167. |

Grime J P, Campbell B D, Mackey J M L et al.Root plasticity, nitrogen capture and competitive ability.In: Atkinson D(ed.), Plant Root Growth, an Ecological Perspective, Blackwell Scientific Publishers, London, UK.1991, 381~397 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279581099_Root_plasticity_nitrogen_capture_and_competitive_ability

|

Haggar J P, Tanner E V J, Beer J W, et al. 1993. Nitrogen dynamics of tropical agroforestry and annual cropping systems. Soil Biol.Biochem., 25: 1363-1378. DOI:10.1016/0038-0717(93)90051-C |

Hahn G, Marschner H. 1998. Cation concentrations of short roots of Norway spruce as affected by acid irrigation and liming. Plant and Soil, 199: 23-27. DOI:10.1023/A:1004206826290 |

Harley J L. 1969. The Biology of Mycorrhiza, 2nd ed. Leonard Hill, Glasgow. |

Harley J L, Smith S E. 1983. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Academic Press, London. |

Harris W F, Kinerson R S, Edwards N T. 1977. Comparison of belowground biomass in natural deciduous forests and loblolly pine plantations. Pedobiologia, 17: 369-381. |

Hermann R K.Growth and production of tree roots: A review.In : Marshall J K (ed.), The Belowground Ecosystem.: A Synthesis of Plant -Associated Processes.Range Sci.Dep.Sci.Ser.No.26.Colorado St.Univ., Ft.Collins, CO, 1977, 7~28

|

Hendrick R L, Pregitzer K S. 1992a. The demography of fine roots in a northern hardwood forest. Ecology, 73: 1094-1104. DOI:10.2307/1940183 |

Hendrick R L, Pregitzer K S. 1992b. Spatial variation in root distribution and growth associated with minirhizotrons. Plant and Soil, 143: 283-288. DOI:10.1007/BF00007884 |

Hendrick R L, Pregitzer K S. 1993a. The dynamics of fine root, length, biomass, and nitrogen content in two northern hardwood ecosystems.Can. J.For.Res., 23: 2507-2520. |

Hendrick R L, Pregitzer K S. 1993b. Patterns of fine root mortality in two sugar maple forests. Nature, 361: 59-61. DOI:10.1038/361059a0 |

Hendrick R L, Pregitzer K S. 1996. Applications of minirhizotrons to understand root function in forests and other natural ecosystems. Plant and Soil, 185: 293-304. DOI:10.1007/BF02257535 |

Hooker J E, Black K E, Perry R L. 1995. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induced alteration to root longevity of poplar. Plant and Soil, 172: 327-329. DOI:10.1007/BF00011335 |

Huttell C.Root distribution and biomass in three Ivory Coast rain forest plots, In: Golley F B, Medina E (eds.), Tropical Ecological System, Ecological Studies II, Springer -Verlag, New York, 1975, 123~130 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284683406_Root_Distribution_and_Biomass_in_Three_Ivory_Coast_Rain_Forest_Plots

|

Jorgensen J R, Well C G, Metz L J. 1980. Nutrient changes in decomposing loblolly pine forest floor. Soil Sci.Soc.Amer.J., 44: 1307-1314. DOI:10.2136/sssaj1980.03615995004400060036x |

Joslin J D, Henderson G S. 1987. Organic matter and nutrients associated with fine root turnover in a white oak stand. For.Sci., 33: 330-346. |

Jonsson I, Fidjeland L, Maghembe J A. 1988. The vertical distribution of fine roots of five tree species and maize in Morogoro, Tanzania, Agro. Systems, 6: 63-69. |

Kavenagh T, Kellman M. 1992. Seasonal pattern of fine root proliferation in a tropical dry forest. Biotropica, 24: 157-165. DOI:10.2307/2388669 |

Keyes M R, Grier C C. 1981. Below -and above-ground biomass and net production in two contrasting Douglas fir stands on low and high productivity sites.Can. J.For.Res., 11: 599-605. |

Khiewtam R S, Ramakrishnan P S. 1993. Litter and fine root dynamics of a relict sacred grove forest at Cherrapunji in north-eastern India. Forest Ecol.Manag., 60: 327-344. DOI:10.1016/0378-1127(93)90087-4 |

Klinge H. 1973. Root mass estimation in lowland tropical rainforest of Central Amazonia, I.Fine root masses of a pale yellow latosol and a giant humus podzol, Trop. Ecol., 14: 29-38. |

Kolesnikov V. 1971. The Root System of Fruit plants. Moscow: Mir Publishers.

|

Kosola K R, Eissenstat D M, Graham J C. 1995. Root demography of mature citrus trees:the influence of Phytophthora nicotianae. Plant and Soil, 171: 283-288. DOI:10.1007/BF00010283 |

Krauss U, Deacon J W. 1994. Root turnover of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.)in soil tubes. Plant and Soil, 166: 259-270. DOI:10.1007/BF00008339 |

Kummerow J.Carbon allocation to root systems in Mediterranean evergreen sclerophylls, In: Margaris N S, Mooney (eds.), Components of productivity of Mediterranean-climate Regions, 1981, 115~120

|

Lawson, G J.Roots in tropical agroforestry system (Appendix 1), In: Cannell M G R, Crout N M J, Dewar RC et al (eds.), Annual Report June 1993-June 1994 of Agroforestry Modelling and Research Coordination, ODA Forestry Research Programme RS651, 1995, 1~25

|

Lehmann J, Weigl D, Droppelmann K, et al. 1997. Nutrient interactions of alley -cropped Sorghum bicolor and Acacia saligna with runoff irrigation in Northern Kenya. Ecol.Appl. |

Lehmann J, Zech W. 1998. Fine root turnover of irrigated hedgerow intercropping in Northern Kenya. Plant and Soil, 198: 19-31. DOI:10.1023/A:1004293910977 |

Liu X, Tyree M T. 1997. Root carbohydrate reserves, mineral nutrient concentrations and biomass in a healthy and a declining sugar maple (Acer saccharum)stand. Tree Physiology, 17: 179-185. DOI:10.1093/treephys/17.3.179 |

Lyr H and Hoffmann G.Growth rates and growth periodicity of tree roots.In: Romberger J A, Mikola P (eds.), International Review of Forestry Research, Academic Press.London.1967, 2: 181~236

|

Majdi H, Persson H. 1993. Spatial Distribution of Fine Roots, Rhizosphere and Bulk-soil Chemistry in an Acidified Picea abies stand. Scand.J.For.Res., 8: 147-155. DOI:10.1080/02827589309382764 |

Majdi H, Nylund J-E. 1996. Does liquid fertilization affect fine root dynamics and lifespan of mycorrhizal short roots?. Plant and Soil, 185: 305-309. DOI:10.1007/BF02257536 |

Marshall J D, Waring R H. 1985. Predicting fine root production and turnover by monitoring root starch and soil temperature, Can. J.For.Res., 15: 791-800. |

McClaugherty C A, Aber J D, Melillo J M. 1984. Decomposition dynamics of fine roots in forested ecosystems. Oikos, 42: 378-386. DOI:10.2307/3544408 |

McClaugherty C A, Aber J D, Melillo JM. 1982. The role of fine roots in the organic matter and nitrogen budgets of two forest ecosystems. Ecology, 63: 1481-1490. DOI:10.2307/1938874 |

Nadelhoffer K J, Aber J D, Mellilo JM. 1985. Fine roots, net primary production, and soil nitrogen availability :A new hypothesis. Ecology, 66: 1377-1390. DOI:10.2307/1939190 |

Nambiar E K S. 1987. Do nutrients retranslocate from fine roots? Can. J.For.Res., 17: 913-918. |

Persson H. 1978. Root dynamics in a young Scots pine stand in central Sweden. Oikos, 30: 508-519. DOI:10.2307/3543346 |

Persson H. 1979. Fine root production, mortality and decomposition in forest ecosystems. Vegetatio, 41: 101-109. |

Persson H. 1980a. Spatial distribution of fine root growth, mortality and decomposition in a young Scots pine stand in central Sweden. Oikos, 34: 77-87. DOI:10.2307/3544552 |

Persson H. 1980b. Dynamics aspects of fine-root growth in a Scots pine stand with and without near -optimum nutrient and water regimes, Acta Phytogeogr. Suec, 68: 101-110. |

Persson H. 1983. The distribution and production of fine roots in boreal forests. Plant Soil, 71: 87-101. DOI:10.1007/BF02182644 |

Persson H, Fircks Y V, Majdi H, et al. 1995. Root distribution in a Norway spruce (Pinus abies (L.)Karst.)stank subjected to drought and ammonium -sulphate application. Plant and Soil, 168/ 169: 161-165. DOI:10.1007/BF00029324 |

Pregitzer, K S, Hendrick R L, Fogel R. 1993. The demography of fine roots in response to patches of water and nitrogen. New Phytol., 125: 575-580. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1993.tb03905.x |

Pregitzer K S, Zak D R, Curtis P S, et al. 1995. Atmospheric CO2, Soil nitrogen and turnover of fine roots. New Phytol, 129: 579-585. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1995.tb03025.x |

Raich J W. 1980. Fine roots regrow rapidly after forest felling. Biotropica, 12: 231-232. DOI:10.2307/2387982 |

Reid J B, Sorensen I, Petrie R A. 1993. Root demography in kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa). Plant Cell Environ., 16: 949-957. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-3040.1993.tb00518.x |

Ritz K, Newman E I. 1985. Evidence for rapid cycling of phosphorus from dying roots to living plants. Oikos, 45: 174-180. DOI:10.2307/3565703 |

Ruark G A, Bockheim J G. 1987. Below -ground biomassof 10-, 20-, and 32-year -old Populustremuloides in Wisconsin. Pedobiologia, 30: 207-217. |

Ruess R W, Van Cleve K, Yarie J, et al. 1996. Contributions of fine root production and turnover to the carbon and nitrogen cycling in taiga forests of the Alaskan interior.Can. J.For.Res., 26: 1326-1336. |

Ruijter F J, Veen B W, Van Oijen M. 1996. A comparison of soil core sampling and minirhizotrons to quantify root development of field-grown potatoes. Plant and Soil, 182: 301-312. DOI:10.1007/BF00029061 |

Rytter R -M, Hansson A -C. 1996. Seasonal amount, growth and depth distribution of fine roots in an irrigated and fertilized Salix viminalis L.plantation. Biomass and Bioenergy, 11(2-3): 129-137. DOI:10.1016/0961-9534(96)00023-2 |

Rytter R -M, Rytter L.Growth, decay and turnover rates of fine roots of basket willows.In: Fine -Root Production and Carbon and Nitrogen Allocation in Basket Willow.Doctoral thesis, Swedish Univ.of Agric.Sci, Uppsala, 1997a

|

Rytter R -M, Rytter L.Seasonal growth patterns of fine roots and shoots in lysimeter -grown basket willows and grey alders.In : Fine -Root Production and Carbon and Nitrogen Allocation in Basket Willow.Doctoral thesis, Swedish Univ.of Agric.Sci, Uppsala, 1997b

|

Sanford R L.Root ecology of mature and successional Amazonian forests, PhD Thesis University of California, Berkley, 1985

|

Sanford R L. 1987. Apogeotropic roots in an Amazon rain forest. Science, 235: 1062-1064. DOI:10.1126/science.235.4792.1062 |

Santantonio D, Hermann RK. 1985. Standing crop, production and turnover of fine roots on dry, moderate and wet sitesof mature Douglas fir in western Oregon, Ann. Sci.For., 42: 113-142. |

Schoettle A W, Fahey T J. 1994. Foliage and fine root longevity of pines. Ecol.Bull, 43: 136-153. |

Singh K P, Srivastava S K. 1985. Seasonal variations in the spatial distribution of root tips in teak (Tectona grandis Linn.f.)plantations in the Varanasi ForestDivision, India. Plant and Soil, 84: 93-104. DOI:10.1007/BF02197870 |

Srivastava S K, Singh K P, Upadhayay R S. 1986. Fine root growth dynamics in teak (Tectona grandis), Can. J.For.Res., 16: 1360-1364. |

Steele S J, Gower S T, Vogel J G, et al. 1997. Root mass, net primary production and turnover in Aspen, Jack pine and Black spruce forests in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, Canada. Tree Physiology, 17: 577-587. DOI:10.1093/treephys/17.8-9.577 |

Strong W L, La Roi G H. 1983. Root depths and successional development of selected boreal forest communities.Can. J.For.Res., 13: 577-588. |

Sundarapandian S M, Swamy P S. 1996. Fine root biomass distribution and productivity patterns under open and closed canopies of tropical forest ecosystems at Kodayar in Western Ghats, South India. For.Ecol.Manage., 86: 181-192. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1127(96)03785-1 |

Teskey R O, Hinckley T M. 1981. Influence of temperature and water potential on root growth of white oak. Physiol.Plant, 52: 363-369. DOI:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1981.tb06055.x |

Thomas S M, Whitehead D, Adams J A, et al. 1996. Seasonal root distribution and soil surface carbon fluxes for one-year-old Pinus radiata trees growing at ambient and elevated carbon dioxide concentration. Tree Physiology, 16: 1015-1021. DOI:10.1093/treephys/16.11-12.1015 |

Toky O P, Bisht R P. 1992. Observationson the rooting pattern of some agroforestry trees in an arid region of north-western India. Agroforestry Systems, 18: 245-263. DOI:10.1007/BF00123320 |

Torquebiau E F, Kwesiga F. 1996. Root development in a Sesbania sesban fallow -maize system in Eastern Zambia. Agrofor.Syst, 34: 193-211. DOI:10.1007/BF00148162 |

Tryon P R, Chapin F S. 1983. Temperature control over root growth and root biomass in taiga forest trees.Can. J.For.Res., 13: 827-833. |

Uhl C, Clark K, Dezzeo N, et al. 1982. Recovery following disturbances of different intensities in the Amazon rain forest of Venezuela. Interciercia, 7: 19-24. |

Vitousek P M, Sanford R L. 1986. Nutrient cycling in moist tropical forests. Annu.Rev.Ecol.Syst., 17: 137-167. DOI:10.1146/annurev.es.17.110186.001033 |

Vogt K A, Grier C C, Meier C E, et al. 1982. Mycorrhizal role in net primary production and nutrient cycling in Abies amabilis ecosystems in western Washington. Ecology, 63: 370. DOI:10.2307/1938955 |

Vogt K A, Vogt D J, Edmonds R L.Effect of stand development and site quality on the amount of fine root growth occurring in the forest floors of Douglas fir stand.In: Root Ecology and its Practical Application.Int.Symp.Gumpenstein, 1982, Bundesanstalt Gumpenstein, A-8952 Irdning, 1983a, 585~594

|

Vogt K A, Moore E E, Vogt D J, et al. 1983b. , Conifer fine root and mycorrhizal root biomass within the forest floors of Douglas fir stands of different ages and site productivities, Can. J.For.Res., 13: 429-435. |

Vogt K A, Grier C C, Gower S T, et al. 1986a. Overestimation of net root production:A real or imaginary problem?. Ecology, 67: 577-579. DOI:10.2307/1938601 |

Vogt K A, Grier C C, Vogt D J. 1986b. Production, turnover and nutrient dynamics of above - and belowground detritus of world forests. Adv.Ecol.Res., 15: 303-377. DOI:10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60122-1 |

Vogt K A, Persson H. 1991a. Measuring growth and development of roots, In :Lassoie J P, Hinckley T M (eds), Techniques and Approachesin Forest Tree Ecophysiology, CRC Press, Inc. Boston: 477-501. |

Vogt K A, Vogt D J, Bloomfield J et al.Input of organicmatter to the soil by tree roots, In: Persson H, McMichael(eds), Plant roots and their environments, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1991b, 171~190

|

Vogt K A, Publicover D A, Bloomfield J, et al. 1993. Belowground responses as indicators of environmental change. Environ.Exp.Bot., 33: 189-205. |

Vogt K A, Vogt D J, Brown S, et al. 1995a. Forest floor and soil organic matter contents and factors controlling their accumulation in boreal temperate and tropical forests. Adv.Soil.Sci.: 159-178. |

Vogt K A, Vogt D J, Asbjornsen H, et al. 1995b. Roots, nutrients and their relationship to spatial patterns. Plant and Soil, 168/169: 113-123. DOI:10.1007/BF00029320 |

Vogt K A, Vogt D J, Palmiotto P A, et al. 1996. Review of root dynamics in forest ecosystems grouped by climate, climatic forest type and species. Plant and Soil, 187: 159-219. |

Waring R H, Schlesinger W H. 1985. Forest Ecosystems:Concepts and Management. Orlando, Florida: Academic Press.

|

2001, Vol. 37

2001, Vol. 37