文章信息

- 吴建国, 艾丽.

- Wu Jianguo, Ai Li.

- 土壤颗粒组分中氮含量及其与海拔和植被的关系

- Nitrogen Content in Soil Particulate Fraction and Its Relationship to the Elevation and the Vegetation

- 林业科学, 2008, 44(6): 10-19.

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2008, 44(6): 10-19.

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2006-09-07

-

作者相关文章

2. 北京科技大学 北京 100083

2. Beijing University of Science and Technology Beijing 100083

土壤中绝大部分的氮以有机氮形式存在,而植物吸收的几乎都是无机氮,所以土壤有机氮必须转化为植物可吸收的有效氮,才能影响植物的生长和植被生产力(Reich et al., 1997)。土壤有机氮可分为自由有机氮、与矿物结合的有机氮(mineral-associated organic N,简称MON)和颗粒有机氮(俗称颗粒氮) (particulate organic N,简称PON),颗粒氮位于土壤团聚体间或内部,其中位于团聚体之间的部分称为自由颗粒氮,位于内部的部分则称为结合态颗粒氮(Christensen, 2001)。由于土壤颗粒组分中的氮被认为是土壤有机氮中的非稳定性部分,所以分析这些土壤颗粒组分中的氮对认识土壤氮的稳定性具有重要意义(Christensen, 2001)。

国际上,测定土壤颗粒氮已经广泛应用于土壤有机氮动态研究,包括根据土壤团聚体氮分布研究土壤有机氮稳定性和分布、土壤物理组分中氮性质、不同植被和土地经营对土壤颗粒组分氮的影响、森林土壤氮有效性与颗粒组分关系等(Six et al., 2001;Koutika et al., 2001;Marriott et al., 2006;Mendham et al., 2004;Christensen, 2001)。但对土壤颗粒有机质氮含量与土壤氮矿化速率关系的研究结果并不一致,一些研究得出土壤颗粒有机质对土壤氮矿化影响很小(Yakovchenko et al., 1998; Whalen et al., 2000), 另一些研究却发现土壤颗粒有机质通过对土壤氮固持作用而促进土壤氮循环(Bremer et al., 1994; Parfitt et al., 2001)。可见,目前对土壤颗粒有机质与土壤氮稳定性关系的认识还十分有限。目前对山地土壤氮属性及其与海拔和植被关系的研究已经有大量报道(Luizão et al., 2004),但关于土壤颗粒组分氮含量及其与海拔和植被关系方面的研究还不多(Gregoricha et al., 2006),所以对土壤氮稳定性与海拔和植被的关系还并不十分清楚,对气候变化后山区土壤氮和植被生产力变化的机制也不十分清楚。

本研究比较分析青藏高原典型山地祁连山北坡土壤颗粒氮含量及其与海拔和植被的关系,为深入研究气候变化对高山区土壤氮分解和植被生产力的影响机制提供一定参考。

1 研究地概况青藏高原海拔高,气候寒冷,称为世界第三极,是气候变化的敏感区和脆弱区(汤懋苍等,1998)。高原四周存在差异悬殊的气候和植被地带(孙鸿烈等,1998)。位于其北沿的祁连山是青藏高原、内蒙古高原和黄土高原的过渡区,也是高原冻土分布的最北端,基带属于暖温带干旱区,其北坡水热差异明显,从低海拔到高海拔依次分布有荒漠草原、干性灌木草原、山地森林、亚高山灌丛草甸和高山寒漠草甸,对应分布着暗灰钙土、灰褐色森林土、淋溶灰褐土和高山草甸土等(熊毅等,1990),这些土壤中的氮素分解对未来气候变化较为敏感, 将对这些植被的生产力产生极大影响。

研究地位于祁连山自然保护区的西水自然保护站(93°30′—103°01′ E, 36°30′—39°30′ N),在祁连山北坡,属于大陆性高寒半干旱、半湿润的森林草原气候。年均气温0.5 ℃,年降水量435.5 mm。主要植被类型包括荒漠草原、干草原、山地森林、灌丛和高寒草甸,主要土壤类型包括灰褐色森林土、山地栗钙土和高山草甸土等。

2 研究方法 2.1 土壤样品的采集和处理2005年9月,从低海拔(2 200 m)到高海拔(3 800 m)设立12块(每块400 m2)样地,这些样地中包括荒漠草原、干草原、山地森林、灌丛草甸和高寒草甸生态系统,以S形取样法在每块样地内随机布设20个点,用土钻(内径5 cm)在0~15和15~35 cm这2个土层采集土样。同时,应用GPS测定不同样地的经纬度和海拔,并估测了不同样地的坡度和坡向,样地概况见表 1。

|

|

把采集的土壤自然风干后通过1 mm土壤筛,以凯氏蒸馏法测全氮含量,单位为g·kg-1。阴坡每个样地每个土层重复20次,半阴坡每样地每个土层重复10次,阳坡3 300 ~3 700 m海拔高度处的样地内的20个土样按土层混和后四分法取样重复3次,3 800 m处样地每个土层重复20次(鲍士旦,2000)。

2.3 土壤颗粒氮的测定把每个样地风干土样按相同土层进行充分混合,过筛(孔径2 mm)后,按四分法准确称取20.00 g,放在装有100 mL (NaPO3)6水溶液(5 g·L-1)的三角瓶(300 mL)中,手摇15 min后,再用往返式摇床震荡18 h(110 r·min-1),把摇好的土壤悬液过53 μm筛,并反复用去离子水冲洗土壤,直到流过筛孔的水变清澈为止,之后把所有没有通过筛孔的土壤用镊子拨在铝盒中,80 ℃下烘干(12 h),并进行称量,这些部分就是土壤颗粒组分,再计算这部分土样占整个土壤样品比例就为土壤颗粒组分比例;把这些土样全部过1 mm土筛,以凯氏蒸馏法测全氮含量,得到土壤颗粒组分氮含量,再换算为土壤颗粒氮含量(g·kg-1)。用这些颗粒组分氮含量除以土壤全氮含量就是土壤颗粒氮比例。每个混合土样重复2次(Camberdella et al., 1993;吴建国等,2002)。

2.4 数据处理对海拔、土层及植被对土壤颗粒组分比例、土壤颗粒氮比例、土壤颗粒组分氮含量、土壤颗粒氮含量与土壤全氮含量影响进行方差分析,然后以最小显著差数法(LSD)检验不同海拔相同土层和相同海拔不同土层,以及相同植被不同土层和相同土层不同植被下这些变量的差异(p<0.05),并回归分析这些变量间的关系。

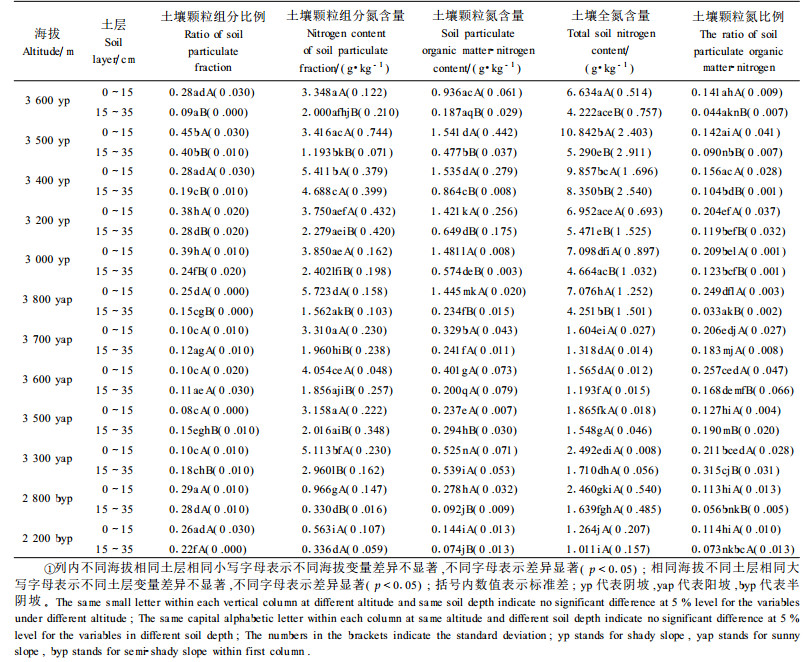

3 结果与分析 3.1 海拔对土壤颗粒组分比例、土壤颗粒氮比例、颗粒组分氮含量、颗粒氮含量和土壤全氮含量的影响不同土层,土壤颗粒组分比例随海拔升高而下降以及土壤颗粒氮比例随海拔升高而增加的趋势都不显著(图 1)。方差分析表明,海拔、土层对土壤颗粒组分比例和土壤颗粒氮比例的影响极显著(表 2)。差异性检验表明,阴坡各海拔处土壤颗粒组分比例都随土层加深而下降(p<0.05)。0~15 cm土层,阳坡3 800 m处土壤颗粒组分比例最高,阴坡3 000、3 200和3 500 m处较高;15~35 cm土层,阴坡3 200和3 500 m处较高,半阴坡2 800 m处较高(p<0.05)。另外,阳坡除3 700 m外,其他海拔处土壤颗粒氮比例都随土层加深而下降,阴坡各海拔处也随土层加深而下降(p<0.05)。0~15 cm土层,阴坡3 000和3 200 m处土壤颗粒氮比例较高, 阳坡3 300和3 800 m处最高;15~35 cm土层,阴坡3 000 m处最高,阳坡3 300 m处最高,半阴坡不同海拔差异不显著(p<0.05)(表 3)。

|

图 1 不同土层土壤颗粒组分比例和土壤颗粒氮比例与海拔的关系 Figure 1 Relationship between ratio of soil particulate fraction or ratio of soil particulate organic matter-nitrogen and altitude in different soil depth |

|

|

|

|

0~15 cm土层,土壤颗粒氮、颗粒组分氮和土壤全氮含量随海拔升高而呈现增加趋势,15~35 cm土层也是同样的趋势(图 2)。

|

图 2 不同土层土壤颗粒组分氮含量、土壤颗粒氮含量和土壤全氮含量与海拔的关系 Figure 2 Relationship between nitrogen content of soil particulate fraction, soil particulate organic matter-nitrogen content or total soil nitrogen content and altitude in different soil depth |

方差分析表明,海拔和土层对土壤颗粒组分氮含量和颗粒氮含量影响极显著,对土壤全氮含量的影响显著(表 2)。差异性检验表明:在阳坡各海拔处土壤颗粒组分氮含量都随土层加深而下降,阴坡除了3 400 m、半阴坡除2 200 m外,其他海拔处都随土层加深而下降(p<0.05);在阴坡各海拔处土壤颗粒氮含量都随土层加深而显著下降,阳坡除3 300和3 600 m外,其他海拔处也随土层加深而显著下降(p<0.05)。在0~15 cm土层,阴坡3 400和3 500 m处土壤全氮含量最高,阳坡3 800 m处较高,半阴坡2 800 m处较高;在15~35 cm土层,阴坡3 400 m处土壤全氮含量最高,阳坡3 800 m处较高,半阴坡2 800 m处较高(p<0.05)。在0~15 cm土层,阴坡3 600 m处土壤颗粒氮含量最低,阳坡3 800 m处较高,半阴坡2 800 m处较高;在15~35 cm土层,阴坡3 400 m处较高,阳坡3 300 m处较高(p<0.05)。在0~15 cm土层,阴坡3 400 m处土壤颗粒组分氮含量较高,阳坡3 300和3 800 m处较高;在15~35 cm土层,阴坡3 400 m处较高,阳坡3 300 m处较高(p<0.05)(表 3)。

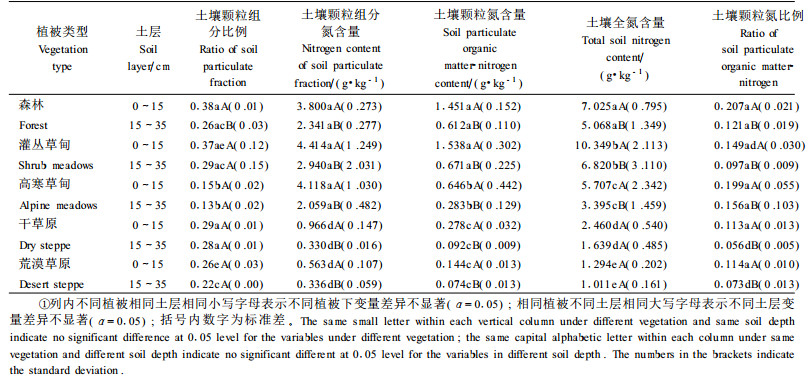

3.2 不同植被下土壤颗粒组分比例、颗粒组分氮含量、颗粒氮含量、土壤全氮含量和土壤颗粒氮比例植被和土层对土壤颗粒组分比例和土壤颗粒氮比例影响都达到显著程度(表 4)。差异性检验表明,除森林植被外,其他植被下不同土层土壤颗粒组分比例差异不显著(p>0.05)(表 5)。不同植被下土壤颗粒组分差异趋势不同:0~15 cm土层,在森林和灌丛草甸土壤中颗粒组分比例较高,高寒草甸中较低,荒漠草原和干草原在2者之间, 森林与灌丛草甸,以及干草原与荒漠草原差异不显著(p<0.05);15~35 cm土层, 森林、灌丛草甸和干草原中较高,荒漠草原次之,高寒草甸中最低,森林、灌丛草甸与干草原间的差异不显著(p<0.05)(表 5)。各植被下土壤颗粒氮比例都随土层加深而下降(p<0.05)。在0~15 cm土层,森林和高寒草甸土壤中颗粒氮比例较高,灌丛草甸、荒漠草原和干草原差异不显著;在15~35 cm土层,森林和高寒草甸中较高,灌丛草甸次之,荒漠草原和干草原中最低(p<0.05)(表 5)。

|

|

|

|

植被和土层对土壤全氮含量、颗粒氮含量和颗粒组分氮含量影响显著(表 4)。差异性检验表明,各植被下颗粒组分氮含量都随土层加深而显著下降,在0~15和15~35 cm土层,这些氮含量都在灌丛草甸中较高,高寒草甸和森林次之,干草原和荒漠草原较低(p<0.05)(表 5)。各植被下土壤颗粒氮含量都随土层加深而下降,其中森林和灌丛草甸最高,高寒草甸次之,干草原和荒漠草原最低,森林、高寒草甸与灌丛草甸中差异不显著(p<0.05)(表 5)。除荒漠草原和干草原外,其他植被下土壤全氮含量都随土层加深而显著下降(p<0.05),0~35 cm土层,灌丛草甸中土壤全氮含量最高,其次是森林和高寒草甸,荒漠草原和干草原中较低(p<0.05)(表 5)。

3.3 土壤全氮含量、土壤颗粒组分比例、土壤颗粒氮比例、土壤颗粒氮含量和颗粒组分氮含量的相互关系图 3显示,土壤颗粒组分比例随土壤全氮含量增加而显著增加(p<0.05),土壤颗粒氮比例随土壤颗粒组分氮含量增加显著增加(p<0.05),土壤颗粒氮含量随土壤颗粒组分氮含量增加而极显著增加(p<0.001),土壤颗粒氮比例随土壤颗粒氮含量增加而增加不显著(p>0.05),土壤颗粒组分氮含量随土壤全氮含量增加而显著增加(p<0.05),土壤颗粒氮含量随土壤全氮含量极显著增加(p<0.001),土壤颗粒氮比例随土壤全氮含量下降不显著(p>0.05),土壤颗粒氮比例随土壤颗粒组分比例下降也不显著(p>0.05)。

|

图 3 土壤全氮含量、颗粒组分比例、颗粒氮比例、颗粒氮含量和颗粒组分氮含量相互关系 Figure 3 The relationships among total soil nitrogen content, ratio of soil particulate fraction, ratio of soil particulate organic matter-nitrogen, soil particulate organic matter -nitrogen content and nitrogen content of soil particulate fraction |

土壤颗粒组分比例反映了土壤中具有非保护结构有机质的相对数量(Camberdella et al., 1994)。由于不同土层水热要素和土壤有机质输入量等的差异,不同土层的颗粒组分不同。本研究表明,阴坡和半阴坡土壤颗粒组分比例随土层加深而下降,阳坡多数海拔处不同土层差异不显著,这与阴坡和半阴坡土壤表层温度低、有利于非稳定性有机质组分积累有关。另外,不同海拔水热要素和土壤有机质输入的差异也使不同海拔处土壤颗粒组分比例不同(Luizão et al., 2004)。本研究表明:不同海拔土壤颗粒组分差异因土层和坡向而异;高海拔土壤表层不稳定部分相对多;底层土壤非稳定性有机质组分比例随海拔变化的趋势不明显。

土壤颗粒氮比例反映了土壤中非保护性氮或非稳定性氮的相对数量(Camberdella et al., 1994)。土壤颗粒氮比例越高,则土壤中氮素中不稳定部分越高,在受到自然因素和人类活动影响后,土壤氮中易分解部分也就越多(Hassink et al., 1995)。本研究表明,阳坡和阴坡不同海拔处土壤颗粒氮比例随土层加深而下降,不同坡向和土层的变化趋势较复杂,与土层、坡向和海拔差异形成的水热因素、土壤性质和有机质输入的差异等有关(Luizão et al., 2004;Gregoricha et al., 2006)。

土壤颗粒组分氮含量直接反映了非保护性组分中的氮含量,土壤颗粒氮含量却反映了土壤中非保护性氮的含量。本研究表明,土壤颗粒氮含量、颗粒组分氮含量和土壤全氮含量总体上都呈现随海拔升高而增加的趋势,土壤颗粒组分氮含量最明显,土壤颗粒氮含量最弱。这与高海拔温度低,有机质腐殖化程度弱,使土壤氮素与矿物质结合程度也弱有关(Christensen, 2001)。

植被直接影响土壤有机质输入量和化学组成及微生物功能,使不同植被下土壤颗粒组分比例不同(Christensen, 2001;熊毅等,1990;Six et al., 2002)。本研究表明,在森林和灌丛草甸土壤表层颗粒组分比例较高,高寒草甸中较低;同时,森林、灌丛草甸和干旱草原土壤底层的颗粒组分比例较高,高寒草甸中最低。Mendham等(2004)研究发现澳大利亚西南部桉树(Eucalyptus)人工林土壤中全氮含量比临近草地土壤中低,但人工林土壤中颗粒氮的比例却要比草地中高,说明不同植被下土壤颗粒氮比例差异与不同植被下土壤全氮含量差异不完全一致。本研究表明,森林和高寒草甸土壤中颗粒氮的比例比灌丛草甸、荒漠草原和干草原高,且这些植被下土壤颗粒氮比例都随土层加深而下降。

植被也会影响土壤颗粒氮、颗粒组分氮及土壤全氮含量(Six et al., 2002)。本研究表明,森林、高寒草甸和灌丛草甸土壤中非稳定性有机氮含量较高。这也主要与森林、草甸和灌丛植被生产力较高、植物残体输入量大以及土壤质地较细等有关(Christensen, 2001)。植物残体化学组成和环境因素也影响土壤有机质中非物理结合组分部分, 进而使土壤颗粒氮含量和颗粒组分氮含量不同(Gregoricha et al., 2006)。本研究中,森林、草甸和灌丛植被形成残体的化学组成、所处海拔的水热要素和土壤性质等差异都可能使土壤颗粒氮含量和颗粒组分氮含量不同(张虎等,2001;Denef et al., 2001)。

土壤全氮含量、颗粒氮含量、颗粒组分氮含量、土壤颗粒组分比例及颗粒氮组分比例这些要素之间具有密切关系(Mendham et al., 2004)。本研究表明,土壤全氮含量越高,土壤中非保护性氮含量也越高,且土壤颗粒组分中氮含量越高,土壤氮中非保护性部分比例也越高,说明土壤颗粒氮含量和颗粒组分氮含量是土壤氮素含量变化的敏感指示部分(Marriott et al., 1998),土壤颗粒氮比例与土壤全氮含量相关性不显著(p>0.5),体现了土壤氮稳定性影响因素的复杂性。

研究表明,在受到气候变化影响后,祁连山中部阴坡海拔3 000、3 200 m处及阳坡海拔3 300、3 800 m处土壤中颗粒氮比例较高,可以推断,在受到气候变化影响后,森林和高寒草甸中非稳定性氮的比例较高,土壤中有效氮相对数量将增多。

鲍士旦. 1999. 土壤农化分析. 北京: 中国农业出版社.

|

孙鸿烈, 郑度. 1998. 青藏高原形成演化与发展. 广州: 广东科技出版社.

|

汤懋苍, 程国栋. 1998. 青藏高原近代气候变化及其对环境的影响. 广州: 广东科技出版社.

|

吴建国, 张小全, 王彦辉, 等. 2002. 土地利用变化对土壤物理组分中有机氮分配影响. 林业科学, 38(4): 19-29. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-7488.2002.04.004 |

熊毅, 李庆逵. 1990. 中国土壤. 北京: 科学出版社.

|

Bremer E, Janzen H H, Johnston A M. 1994. Sensitivity of total, light fr action and mineralizable organic matter to management practices in a Lethbridge soil. Canadian Journal of Soil Science, 74: 131-138. DOI:10.4141/cjss94-020 |

Camberdella C A, Elliott E T. 1993. Methods of physical characterization of soil organic matter fractions. Geoderma, 56: 449-457. DOI:10.1016/0016-7061(93)90126-6 |

Camberdella C A, Elliott E T. 1994. Carbon and nitrogen dynamics of soil organic matter fractions from cultivated grassland soils. Soil Science Society of American Journal, 58: 123-130. DOI:10.2136/sssaj1994.03615995005800010017x |

Christensen B T. 2001. Physical fractionation of soil and structural and functional complexity in organic matter turnover. European Journal of Soil Science, 52: 345-353. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2389.2001.00417.x |

Denef K, Six J, Paustian K, et al. 2001. Importance of macroaggregate dynamics in controlling soil carbon stabilization: short term effects of physical disturbance induced by dry-wet cycles. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 35(15): 2145-2153. |

Gregoricha E G, Beareb M H, McKima U F, et al. 2006. Chemical and biological characteristics of physically uncomplexed organic matter. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 70: 967-974. DOI:10.2136/sssaj2005.0111 |

Hassink J. 1995. Decomposition rate constants of size and density fractions of soil organic matter. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 59: 1631-1635. DOI:10.2136/sssaj1995.03615995005900060018x |

Koutika L S, Hauser S, Henrot J. 2001. Soil organic matter assessment in natural regrowth, Pueraria phaseoloides and Mucuna pruriens fallow. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 33(7/8): 1095-1101. |

Luizão R C C, Luizão F J, Paiva R Q, et al. 2004. Variation of carbon and nitrogen cycling processes along a topographic gradient in a Amazonian forest. Global Change Biology, 10: 592-600. DOI:10.1111/gcb.2004.10.issue-5 |

Marriott E E, Wander M M. 1998. Total and labile soil organic matter in organic and conventional farming systems. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 62(6): 1704-1711. DOI:10.2136/sssaj1998.03615995006200060031x |

Marriott E E, Wander M. 2006. Qualitative and quantitative differences in particulate organic matter fractions in organic and conventional farming systems. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 38(7): 1527-1536. |

Mendham D S, Heagney E C, Corbeels M, et al. 2004. McMurtrie soil particulate organic matter effects on nitrogen availability after afforestation with Eucalyptus globulus. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 36(7): 1067-1074. |

Parfitt R L, Salt G J. 2001. Carbon and nitrogen mineralization in sand, silt, and clay fractions of soils under maize and pasture. Australian Journal of Soil Research, 39: 361-371. DOI:10.1071/SR00028 |

Reich P B, Grigal D F, Aber J D, et al. 1997. Nitrogen mineralization and productivity in 50 hardwood and conifer stands on diverse soils. Ecology, 78: 335-347. DOI:10.1890/0012-9658(1997)078[0335:NMAPIH]2.0.CO;2 |

Six J, Conant R T, Paul E A, et al. 2002. Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant and Soil, 241: 155-176. DOI:10.1023/A:1016125726789 |

Six J, Guggenberger G, Paustian K, et al. 2001. Sources and composition of soil organic matter fractions between and within soil aggregates. European Journal of Soil Science, 52: 607-618. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2389.2001.00406.x |

Whalen J K, Bottomly P J, Myrold D D. 2000. Carbon and nitrogen mineralization from light- and heavy-fraction additions to soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 32: 1345-1352. DOI:10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00040-7 |

Yakovchenko V P, Sikora L J, Millner P D. 1998. Carbon and nitrogen mineralization of added particulate and macroorganic matter. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 30: 2139-2146. DOI:10.1016/S0038-0717(98)00096-0 |

2008, Vol. 44

2008, Vol. 44