空气动力学直径不超过2.5 μm的颗粒物是主要空气颗粒物污染物, 称之为PM2.5(Fine particulate matter, PM2.5), 由空气中的固体颗粒和液滴组成(Block et al., 2009).PM2.5对呼吸系统的毒性影响已经成为全世界关注的问题, 长期暴露于PM2.5易于诱发各种肺部相关疾病(Neri et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019b), 世卫组织统计及流行病学资料显示每年均有上万人死于PM2.5相关的室外空气污染(Jung et al., 2019).PM2.5的致病性取决于它们的粒径大小、成分组成和来源等, 我国北方地区PM2.5主要由可溶性盐、金属元素、酸性氧化物、有机污染物、细菌、真菌和病毒等组成(焦周光等, 2016), 其中PM2.5中的金属成分一般含Fe、AL、Pb、Mn、Mg、Cu等元素(刘爱明等, 2011).研究显示, 人长期暴露于PM2.5轻则会引起呼吸系统相关细胞发生氧化应激、炎症反应、免疫异常、细胞内钙离子失调以及能量代谢紊乱等(Abrams et al., 2017; Rao et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018a), 重则引起呼吸系统相关细胞发生多种形式的死亡, 如细胞凋亡(Piao et al., 2018)、坏死(Wang et al., 2018b)、自噬(Zhu et al., 2018)、衰老和炎症介导的细胞死亡(Li et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2019).但由于PM2.5成分与样品发生季节及地域等有关, 其引起呼吸系统疾病的机制及规律还远未揭示.

最近有报道显示PM2.5暴露循环系统内皮细胞后, 可引起细胞内铁超载和氧化还原失衡, 并诱导细胞铁死亡(Ferroptosis)(Wang et al., 2019).这提示PM2.5暴露导致呼吸系统疾病可能还存在新的损伤机制.铁死亡(Dixon et al., 2012)是近年发现的一种细胞死亡方式, 是与铁离子有关并依赖脂质过氧化的程序性细胞死亡.具体表现为细胞内ROS代谢、铁代谢、氨基酸和谷胱甘肽代谢障碍(Stockwell et al., 2017).目前铁死亡诱导剂多数通过消耗谷胱甘肽(Glutathione, GSH)或使谷胱甘肽依赖性抗氧化酶-谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶4(Glutathione peroxidase 4, GPX4)失活(Cozza et al., 2017), 致使体内过多的膜磷脂氢过氧化物(Phospholipid hydroperoxides, PL-OOH)与不稳定的铁反应后生成烷氧基和过氧自由基, 进一步引起细胞膜中含多不饱和脂肪酸(Polyunsaturated fatty acids, PUFA)的磷脂(Phospholipid, PLs)持续氧化(Miotto et al., 2020), 最终导致质膜变薄并增加膜的曲率促使细胞膜破裂(Agmon et al., 2018).铁死亡发生时, 会出现细胞水平上的形态特征变化, 包括双层膜断裂和线粒体皱缩、线粒体嵴减少等.最新的研究显示铁死亡与肺部疾病包括急性肺损伤(Zhou et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020)、慢性阻塞性肺疾病(Park et al., 2019)、肺纤维化(Li et al., 2019a)和肺部炎症等密切相关, 而肺是PM2.5的重要作用器官, 因此我们大胆假设PM2.5可能通过引起肺部细胞铁死亡, 从而促进肺部疾病的发生发展.

本文以人呼吸系统支气管上皮细胞16HBE为模型, 研究了经PM2.5暴露后, 16HBE细胞产生的铁过载及铁死亡效应, 进一步证实了PM2.5可以引起呼吸系统上皮细胞铁死亡, 从而为更加全面地揭示PM2.5引起呼吸系统疾病的机制提供新的理论依据.

2 材料和方法(Materials and methods) 2.1 主要材料与试剂本实验所用细胞为人源支气管上皮细胞(Human bronchial epithelial cell line, 16HBE), 由中国科学院国家纳米科学中心惠赠.

主要试剂:CCK-8检测试剂盒(同仁公司, 日本);MDA检测试剂盒(碧云天生物技术, 上海);GSH检测试剂盒(碧云天生物技术, 上海);铁死亡荧光试剂(Fe2+荧光法)FerroOrange探针F374;脂质过氧化物荧光探针Liperfluo探针L248(同仁公司, 日本);铁螯合剂(Deferoxamine mesylate, DFOM), HY-B0988;铁死亡抑制剂(Ferrostatin-1, Fer-1), HY-100579(MCE公司, 中国).

2.2 制备PM2.5样品使用TH-1000C型智能大流量空气颗粒物采样器采集北京市2018.11—2019.1的空气污染物PM2.5至石英纤维膜上, 用75% 乙醇浸湿石英纤维膜, 裁剪成合适大小放入烧杯中, 加无菌水冰浴超声5~10 min, 重复3次收集洗脱液, 洗脱液经无菌纱布过滤后真空冷冻干燥称重, 最后用无菌水溶解PM2.5冻干粉末, 制成20 mg·mL-1的储存液于-80 ℃保存待用.

2.3 细胞培养和PM2.5暴露处理将16HBE细胞接种在完全型1640培养液(10% 胎牛血清、1% 青霉素、链霉素)中, 37 ℃、5% CO2培养箱饱和湿度条件下贴壁传代培养, 经2~3次传代, 取对数生长期的细胞铺96/6孔板, 过夜贴壁后做PM2.5暴露处理.将PM2.5溶液进行超声振荡使其分散均匀, 用含2% FBS的1640培养液稀释成实验所需浓度, 将16HBE细胞暴露于上述PM2.5悬液中培养后用于后续相应实验检测.

2.4 细胞活性检测取对数生长期的16HBE细胞以8×103个·孔-1密度接种于96孔板, 37 ℃、5%CO2过夜培养贴壁后, 去除原培养基, PBS清洗后加入浓度梯度为25、50、100、200、400、800 μg·mL-1的PM2.5溶液处理细胞, 100 μL·孔-1, 24 h后加入10 μL CCK-8溶液, 避光孵育2 h, 多功能酶标仪下读取450 nm处OD值.细胞存活率R的计算公式如下:

|

(1) |

将16HBE细胞接种于25 cm2培养瓶中, 37 ℃、5% CO2条件下过夜培养至贴壁, 去除原有培养基, PBS清洗3次, 加入200 μg·mL-1的PM2.5溶液培养24 h, 收集细胞, 使用戊二醛固定, 使用透射电子显微镜观察线粒体结构.

2.6 细胞内Fe2+检测将16HBE细胞以2×105个·孔-1接种至共聚焦小皿, 37 ℃、5% CO2条件下过夜培养贴壁后, 去除原有培养基, 用无血清培养基清洗3次, 加入IC50浓度(200 μg·mL-1)的PM2.5溶液处理24 h后, 再次去除原有工作液的上清, 加入1 μmol·L-1的Ferro Orange工作液在37 ℃、5% CO2条件下培养30 min, 在激光共聚焦显微镜下观察细胞.

2.7 细胞内LPO MDA GSH含量检测将16HBE细胞以2×105个·孔-1接种至共聚焦小皿, 37 ℃、5% CO2条件下过夜培养至贴壁, 去除原有培养基, PBS清洗3次, 加入200 μg·mL-1的PM2.5溶液培养24 h后, 去除上清, PBS清洗3次, 加入5 μmol·L-1的Liperfluo溶液, 37 ℃、5% CO2条件下培养30 min, 在激光共聚焦显微镜下观察细胞.

用PBS清洗细胞3次, 裂解细胞后取上清液, 采用生化法, 按照MDA检测试剂盒说明书和GSH检测说明书测定, 并用BCA蛋白定量法测出各样品的蛋白浓度, 并以此计算细胞内的MDA和GSH含量.

2.8 铁死亡相关基因表达检测将16HBE细胞以5×105个·孔-1接种在6孔板中, 37 ℃、5% CO2条件下过夜培养至贴壁, 加入200 μg·mL-1的PM2.5溶液培养24 h.使用Trizol法提取总RNA, 根据制造商的说明书, 使用PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit(Takara)将1 μg RNA逆转录成cDNA.使用SYBR Premix DimerEraser (Takara) 试剂盒, 用ViiA7实时定量PCR仪进行qPCR分析(引物序列见表 1).荧光定量PCR反应条件:95 ℃预变性30 s, 95 ℃变性5 s, 55 ℃退火延伸30 s, 共40个循环.以GAPDH的CT值为内参, 目的基因CT值采用2-ΔΔCT计算后的比值即为各基因的相对表达水平.

| 表 1 实时荧光定量PCR引物序列 Table 1 Primers used in real time PCR |

实验数据以均值±标准差(x±s)表示, 所有实验重复3次, 统计学分析软件为GraphPad Prism 8和SPSS, 采用独立样本t检验、方差检验的方法分析数据, 作图软件为GraphPad Prism 8.p<0.05时, 则认为差异有统计学意义.

3 结果(Results) 3.1 铁死亡抑制剂降低PM2.5对16HBE细胞的毒性作用通过CCK-8检测PM2.5对16HBE细胞存活率的影响, 随PM2.5浓度增高, 其对细胞的毒性增加, 计算得出PM2.5对16HBE细胞的IC50为200 μg·mL-1(后续实验均以200 μg·mL-1的PM2.5溶液处理细胞), 同时检测出铁死亡抑制剂DFOM和Fer-1分别在DFOM(6.25±5) μmol·L-1、Fer-1(12.50±5)μmol·L-1浓度时对细胞无毒性作用.采用此浓度的铁死亡抑制剂预先处理细胞1 h后再进行PM2.5暴露, 细胞存活率明显升高, 表明铁死亡是参与PM2.5诱导的上皮细胞损伤的重要死亡方式.

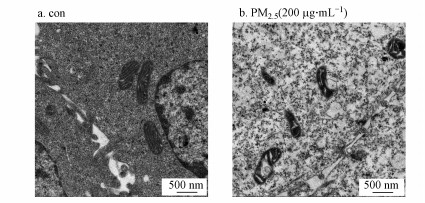

3.2 PM2.5暴露诱发16HBE细胞线粒体形态结构改变细胞铁死亡在形态学上不同于凋亡、坏死和自噬, 有着自身的超微结构特点, 电子显微镜可以观察到发生铁死亡的细胞中线粒体明显皱缩、双层膜密度增加(Yang et al. 2016b).在本研究中, PM2.5暴露后透射电子显微镜观察细胞线粒体的超微结构显示, 与对照处理的16HBE细胞相比, PM2.5暴露处理的细胞线粒体体积更小, 并出现皱褶减少等铁死亡细胞形态特征(2b), PM2.5暴露组线粒体大小尺寸明显变小, 且结构呈现出明显异常, 进一步证实了铁死亡的发生(图 2).

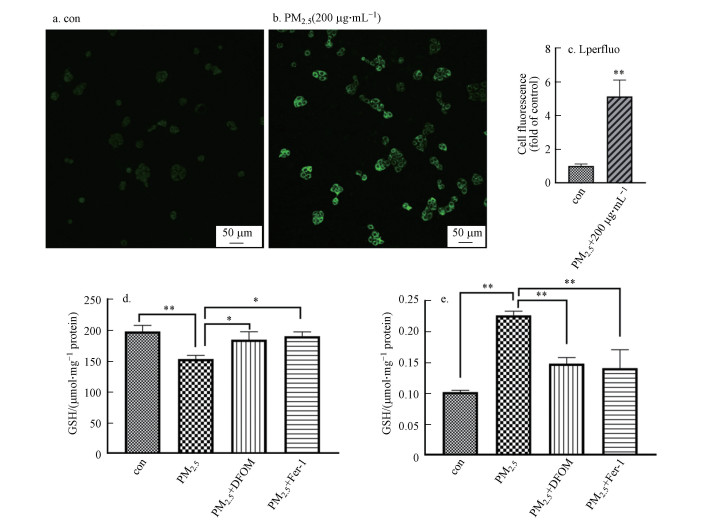

3.3 PM2.5暴露诱发16HBE细胞内铁过载由于细胞发生铁死亡时会出现铁过载, 因此本研究用FerroOrange探针来评估暴露于PM2.5后16HBE细胞内的铁浓度.铁是通过酶促反应或非酶促反应形成脂质过氧化物的重要因素, 在细胞中Fe2+会与探针反应生成稳定的有色络合物.PM2.5处理细胞后, 共聚焦显微镜下可以观察到16HBE细胞内Fe2+探针荧光强度显著增加(3b), 且Fe2+探针荧光遍布整个细胞质中.

3.4 PM2.5暴露诱发16HBE细胞内谷胱甘肽降低, 脂质过氧化水平增加脂质过氧化在铁死亡的过程中起着核心作用, 其最终代谢产物磷脂氢过氧化物的过度积累被认为是铁死亡的标志事件(Yang et al. 2016b).本研究采用脂质过氧化氢探针来检测细胞内脂质过氧化物(Lipid peroxidation, LPO)的生成情况.结果显示, 16HBE细胞暴露于PM2.5后, 细胞内LPO生成相关的荧光信号强度显著增强(图 4b).GSH是细胞内重要的抗氧化剂, 丙二醛(Malondialdehyde, MDA)是氧化应激的典型标志物, 二者均是检测铁死亡的重要指标.细胞暴露于PM2.5后, 细胞内GSH含量降低, MDA显著增加, 而铁死亡抑制剂可以显著减少PM2.5暴露对GSH的损耗(4d)以及PM2.5暴露引起的MDA增加(图 4e).说明PM2.5引起细胞发生铁死亡相关的氧化应激, 胞内氧化还原水平失衡.

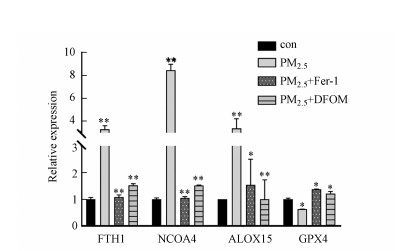

3.5 PM2.5暴露诱导16HBE细胞中铁死亡相关基因的表达改变铁死亡过程中涉及到多种基因发生变化, 尤其是铁代谢和氧化应激相关的基因, 例如铁蛋白重链(FTH1)、核受体共激活因子4(NCOA4)、脂质过氧化中的关键酶类(ALOXs)和重要的抗氧化酶(GPX4)等.16HBE细胞暴露于200 μg·mL-1的PM2.5后, RT-qPCR的结果显示, FTH1、NCOA4、ALOX15表达量较阴性对照组均显著性增加, GPX4活性在PM2.5处理组中显著性降低(图 5), 而以上基因在铁死亡抑制剂和铁螯合剂预处理组中均可以被有效恢复, 说明PM2.5暴露改变了16HBE细胞内铁稳态及铁死亡相关基因的应激表达.

4 讨论(Discussion)颗粒物随着呼吸进入人体, 通过沉降等其他过程沉积在支气管和肺部(Darquenne, 2014), 其对呼吸系统的影响取决于粒径的大小, 即不同粒径的颗粒物(Particulate matter, PM)在呼吸系统中的转运效率和渗透率不同.PM2.5因其颗粒直径小、表面积大和毒素吸收能力强而能够被吸入呼吸道深部并沉积在终末细支气管和肺泡中(Esposito et al., 2016), 对呼吸系统产生刺激作用, 并与一系列呼吸系统疾病的发病密切相关(Yamato et al., 1994).支气管上皮细胞在启动和增强呼吸系统防御机制中起着至关重要的作用, 是抵抗内源性因素和外部刺激的第一道防线(Mills et al., 1999) (Oh et al., 2011).有关病原体及环境危险因子导致肺组织尤其是肺上皮细胞毒性损伤机制的研究备受关注.

铁死亡是新发现的细胞死亡形式, 由具有铁依赖性的脂质过氧化作用来驱动膜损伤(Stockwell et al., 2017).近年来的研究发现许多有害因素和药物如PM2.5(Wang et al., 2019)、索拉非尼(Lachaier et al., 2014)、甲醛(李晓娜, 2018)、顺铂(Guo et al., 2018)等也可以诱导细胞发生铁死亡.其中PM2.5吸附的外源性铁可被细胞摄取, 并参与细胞内的铁代谢反应进而引发细胞铁死亡(Wang et al., 2019).发生铁死亡的细胞有着不同于凋亡等其他程序性死亡方式的形态学特征, 例如铁死亡会出现细胞膜断裂和出泡, 细胞核大小正常但缺乏染色质凝聚等.最主要的形态特征在电镜下表现为线粒体变小、膜密度增高、线粒体嵴减少或消失以及线粒体外膜断裂等(Dixon et al., 2012).铁死亡的两个主要生化特征是铁过载和脂质过氧化物积累.脂质过氧化是铁死亡的关键因素, 而铁在脂质过氧化时发挥重要作用, 铁的吸收、储存和利用等都参与铁死亡过程的调控.铁是人体中不可缺少的微量元素之一, 其含量在细胞和整个体内均保持平衡状态, 铁稳态在正常细胞的存活和发育中起着重要作用, 而铁的过度积累则是铁死亡的标志之一.通常进入胞内的铁以铁-蛋白质复合物(Ferritin, 由重链FTH和轻链FTL构成)的形式存储和运输, 当细胞异常摄入过多的铁时, 即使铁蛋白过量表达也无法容纳源源不断摄入的铁, 这时核受体共激活因子4(NCOA4)介导的铁自噬被特异性激活(Yang et al., 2019).铁自噬作用释放的Fe2+可以增加脂质过氧化的关键酶─脂氧合酶(ALOXs)的活性, 也可以通过Fenton反应直接产生过量的ROS而增加氧化损伤(Geng et al., 2018).超载的铁无论是参与自发氧化还是酶促氧化均会促进脂质过氧化物的形成(Stoyanovsky et al., 2019).脂质过氧化是一种自由基驱动的反应, 产物包括最初的脂质过氧化物(Lipid peroxidation, LPO)和随后的反应物醛类(例如, 丙二醛(MDA)).在铁死亡发生的过程中, LPO和MDA含量均会增加.LPO主要是膜磷脂中多不饱和脂肪酸(PUFA)被ROS氧化生成的磷脂氢过氧化物, 其可以被GPX4转化为相应的磷脂醇(Hydroxyl PEG-modified liposomes, PLOH)来减轻脂质过氧化的危害(Yang et al., 2016a; Wang et al., 2018b; Anthonymuthu et al., 2020).小分子诱导剂在诱导铁死亡发生时, LPO过度积累, GSH被耗竭, GPX4会失活(Gaschler et al. 2018).

本课题组前期对北京地区PM2.5化学成分的分析发现Fe元素的富集因子值大于2 (邵桐等, 2017).因此推测PM2.5细胞暴露中, 成分铁可能参与细胞应激损伤过程.本研究通过PM2.5暴露人支气管上皮细胞系16HBE细胞, 发现PM2.5可导致16HBE细胞存活率明显下降, 而铁死亡抑制剂DFOM和Fer-1可提高细胞存活率, 减少PM2.5对16HBE的暴露毒性(图 1), 证明PM2.5致16HBE细胞毒性中存在铁死亡机制.线粒体特征性超微结构(图 2b)、细胞内铁过载(图 3b)和氧化应激改变(图 4)也进一步证实了PM2.5诱导的16HBE细胞铁死亡效应.细胞内铁储存蛋白(重链FTH1或者轻链FTL)的异常变化会影响铁的代谢过程, 本研究结果显示16HBE细胞内FTH1和NCOA4的表达量显著升高(图 5), 这提示PM2.5暴露可导致16HBE胞内铁储存及释放的游离Fe2+均增加.细胞内脂质过氧化氢LPO水平升高, GSH含量降低, MDA含量增加, 说明PM2.5引起铁死亡时细胞内氧化水平升高, 而GPX4表达量降低, 则证实当细胞受到PM2.5的刺激时损害了细胞内的抗氧化机制.本课题组的进一步研究显示, PM2.5暴露诱导16HBE细胞内参与Fenton反应的关键酶ALOX15的表达水平显著升高(图 5), 而铁螯合剂DFOM可以显著减轻PM2.5对16HBE细胞抗氧化系统的损害, 使GSH含量升高、MDA含量降低并且使高表达的ALOX15恢复至正常水平(图 4d~4e和图 5), 这说明暴露细胞中是由于铁过载而引起细胞内氧化还原失衡, 从而提高脂质过氧化水平.同时证实铁过载和过度脂质过氧化是16HBE细胞铁死亡的重要原因.因此, 本研究结果证实PM2.5对人呼吸系统产生的毒性损伤中有铁死亡的参与, 并且PM2.5是通过促使细胞内铁过载和氧化还原失衡来诱发细胞发生铁死亡.实际上, PM2.5会导致细胞产生多种死亡方式, 如细胞坏死、细胞凋亡等, 其中, 细胞铁死亡、细胞坏死等还与机体细胞炎性应激有密切关系(Tsurusaki et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2020).PM2.5暴露引起肺组织损伤的机制复杂, PM2.5诱导铁死亡与其它各种死亡途径之间的联系以及与肺组织细胞炎性效应关系机制都亟需深入探究.

|

| 图 1 PM2.5对16HBE细胞的毒性作用 (a. PM2.5暴露24 h后16HBE细胞存活率;b. 使用/不使用铁死亡抑制剂Fer-1(12.50 μmol·L-1)和DFOM(6.25 μmol·L-1)预处理的PM2.5暴露24 h后16HBE细胞存活率*p<0.05, **p<0.01) Fig. 1 The effect of PM2.5 on 16HBE cytotoxicity (a. Cell viability in16HBE cell in response to PM2.5 for 24 h; b. Cell in 16HBE cells by exposure to PM2.5 for 24 h pretreated with/without ferroptosis inhibitors of Fer-1 (12.50 μmol·L-1) and DFOM(6.25 μmol·L-1). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) |

|

| 图 2 通过透射电子显微镜观察PM2.5暴露前后16HBE细胞内线粒体形态变化 (a.对照组;b.PM2.5处理组) Fig. 2 The morphological changes of mitochondria in 16HBE cells before and after PM2.5 exposure were observed by transmission electron microscope (a. control group; b. PM2.5 exposure group) |

|

| 图 3 PM2.5暴露后16HBE细胞内Fe2+的含量 (a.对照组;b.PM2.5处理组;c.荧光统计分析*p<0.05, **p<0.01) Fig. 3 The Fe2+ content in 16HBE cells after PM2.5 exposure (a. control group; b. PM2.5 exposure group; c. Fluorescence statistical analysis *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) |

|

| 图 4 铁死亡相关的氧化还原失衡标志物检测 (a~c.PM2.5暴露24 h, 以脂质过氧化氢为探针检测16HBE细胞内LPO的释放情况;d~e.使用/不使用Fer-1(12.50 μmol·L-1)和DFOM(6.25 μmol·L-1)铁死亡抑制剂预处理的PM2.5暴露24 h后16HBE细胞内GSH和MDA含量. a.对照组;b.PM2.5处理组;c.荧光统计分析*p<0.05, **p<0.01) Fig. 4 Detection of redox imbalance markers related to ferroptosis (a~b. The GSH and MDA content in 16HBE cells by exposure to PM2.5 for 24 h pretreated with/without ferroptosis inhibitors of Fer-1 (12.5 μmol·L-1) and DFOM (6.25 μmol·L-1). c~e.PM2.5 exposure for 24 h, use lipid hydrogen peroxide as a probe to detect the release of LPO in 16HBE cells (a. control group; b. PM2.5 exposure group; c. Fluorescence statistical analysis *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) |

|

| 图 5 PM2.5暴露后16HBE细胞中差异表达的基因 (*p<0.05, **p<0.01) Fig. 5 Differentially expressed genes in 16HBE cells after PM2.5 exposure (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) |

本实验结果表明, PM2.5暴露诱发16HBE细胞毒性效应中, 细胞内产生铁积累、胞内脂质过氧化物水平上升、铁死亡特征性线粒体超微结构的改变及铁死亡相关基因表达的改变, 铁死亡抑制剂可有效减少PM2.5暴露诱发的16HBE细胞毒性.因此, PM2.5可通过诱发人肺上皮细胞铁死亡, 引起肺组织的毒性损伤作用.

Abrams J Y, Weber R J, Klein M, et al. 2017. Associations between ambient fine particulate oxidative potential and cardiorespiratory emergency department visits[J]. Environmental Health Perspect, 125: 107008. DOI:10.1289/EHP1545 |

Agmon E, Solon J, Bassereau P, et al. 2018. Modeling the effects of lipid peroxidation during ferroptosis on membrane properties[J]. Scientific Reports, 8: 5155. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-23408-0 |

Anthonymuthu T S, Tyurina Y Y, Sun W Y, et al. 2020. Resolving the paradox of ferroptotic cell death: Ferrostatin-1 binds to 15LOX/PEBP1 complex, suppresses generation of peroxidized ETE-PE, and protects against ferroptosis[J]. Redox Biology, 38: 101744. |

Block M L, Calderon-Garciduenas L. 2009. Air pollution: mechanisms of neuroinflammation and CNS disease[J]. Trends Neurosci, 32: 506-516. DOI:10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.009 |

Chen M, Qin X, Qiu L, et al. 2018. Concentrated ambient PM2.5-Induced inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in a murine model of Neural IKK2 deficiency[J]. Environmental Health Perspect, 126: 027003. DOI:10.1289/EHP2311 |

Cozza G, Rossetto M, Bosello-Travain V, et al. 2017. Glutathione peroxidase 4-catalyzed reduction of lipid hydroperoxides in membranes: The polar head of membrane phospholipids binds the enzyme and addresses the fatty acid hydroperoxide group toward the redox center[J]. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 112: 1-11. DOI:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.07.010 |

Darquenne C. 2014. Aerosol deposition in the human lung in reduced gravity[J]. Journal of Aerosol Medicine and Pulmonary Drug Delivery, 27: 170-7. DOI:10.1089/jamp.2013.1079 |

Dixon S J, Lemberg K M, Lamprecht M R, et al. 2012. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death[J]. Cell, 149: 1060-72. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042 |

Esposito E, I D, B G, et al. 2016. A new co-micronized composite containing palmitoylethanolamide and polydatin shows superior oral efficacy compared to their association in a rat paw model of carrageenan-induced inflammation[J]. European Journal of Pharmacology, 782: 107-18. DOI:10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.03.033 |

Gaschler M M, Andia A A, Liu H, et al. 2018. FINO2 initiates ferroptosis through GPX4 inactivation and iron oxidation[J]. Nature Chemical Biology, 14: 507-515. DOI:10.1038/s41589-018-0031-6 |

Geng N, Shi B J, Li S L, et al. 2018. Knockdown of ferroportin accelerates erastin-induced ferroptosis in neuroblastoma cells[J]. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 22: 3826-3836. |

Guo J, Xu B, Han Q, et al. 2018. Ferroptosis: A novel anti-tumor action for cisplatin[J]. Cancer Research and Treatment, 50: 445-460. DOI:10.4143/crt.2016.572 |

Jung E J, Na W, Lee K E, et al. 2019. Elderly mortality and exposure to fine particulate matter and ozone[J]. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 34: 311. DOI:10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e311 |

焦周光, 李敬云, 温占波, 等. 2016. 北京城区夏季PM2.5及不同组分化学和生物成分分析[J]. 环境工程学报, 10: 5009-5015. DOI:10.12030/j.cjee.201601018 |

李晓娜. 2018. 甲醛通过上调Warburg效应诱导HT22细胞铁死亡[D]. 衡阳: 南华大学

|

刘爱明, 杨柳. 2011. 大气重金属离子的来源分析和毒性效应[J]. 环境与健康杂志, 28: 839-842. |

Lachaier E, Louandre C, Godin C, et al. 2014. Sorafenib induces ferroptosis in human cancer cell lines originating from different solid tumors[J]. Anticancer Research, 34: 6417-22. |

Li R, Kou X, Xie L, et al. 2015. Effects of ambient PM2.5 on pathological injury, inflammation, oxidative stress, metabolic enzyme activity, and expression of c-fos and c-jun in lungs of rats[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 22: 20167-76. DOI:10.1007/s11356-015-5222-z |

Li X, Duan L, Yuan S, et al. 2019a. Ferroptosis inhibitor alleviates Radiation-induced lung fibrosis (RILF) via down-regulation of TGF-beta1[J]. Journal of Inflamm (Lond), 16: 11. DOI:10.1186/s12950-019-0216-0 |

Li Y, Cao Y, Xiao J, et al. 2020. Inhibitor of apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53 inhibits ferroptosis and alleviates intestinal ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute lung injury[J]. Cell Death and Differentiation, 27: 2635-2650. DOI:10.1038/s41418-020-0528-x |

Li Y, Dong T, Jiang X, et al. 2019b. Chronic and low-level particulate matter exposure can sustainably mediate lung damage and alter CD4 T cells during acute lung injury[J]. Molecular Immunology, 112: 51-58. DOI:10.1016/j.molimm.2019.04.033 |

Liang H, Qiu H, Tian L. 2018. Short-term effects of fine particulate matter on acute myocardial infraction mortality and years of life lost: A time series study in Hong Kong[J]. Science of the Total Environmental, 615: 558-563. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.266 |

Mills P R, Davies R J, Devalia J L. 1999. Airway epithelial cells, cytokines, and pollutants[J]. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 160: 38-43. DOI:10.1164/ajrccm.160.supplement_1.11 |

Miotto G, Rossetto M, Di Paolo M L, et al. 2020. Insight into the mechanism of ferroptosis inhibition by ferrostatin-1[J]. Redox Biology, 28: 101328. |

Neri T, Pergoli L, Petrini S, et al. 2016. Particulate matter induces prothrombotic microparticle shedding by human mononuclear and endothelial cells[J]. Toxicol in Vitro, 32: 333-8. DOI:10.1016/j.tiv.2016.02.001 |

Oh S M, Kim H R, Park Y J, et al. 2011. Organic extracts of urban air pollution particulate matter (PM2.5)-induced genotoxicity and oxidative stress in human lung bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B cells)[J]. Mutation Research, 723: 142-51. |

Park E J, Park Y J, Lee S J, et al. 2019. Whole cigarette smoke condensates induce ferroptosis in human bronchial epithelial cells[J]. Toxicology Letters, 303: 55-66. |

Piao M J, Ahn M J, Kang K A, et al. 2018. Particulate matter 2.5 damages skin cells by inducing oxidative stress, subcellular organelle dysfunction, and apoptosis[J]. Arch Toxicology, 92: 2077-2091. |

Rao X, Zhong J, Brook R D, et al. 2018. Effect of particulate matter air pollution on cardiovascular oxidative stress pathways[J]. Antioxid Redox Signal, 28: 797-818. |

Stockwell B R, Friedmann Angeli J P, Bayir H, et al. 2017. Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease[J]. Cell, 171: 273-285. |

Stoyanovsky D A, Tyurina Y Y, Shrivastava I, et al. 2019. Iron catalysis of lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis: Regulated enzymatic or random free radical reaction?[J]. Free Radic Biology Medicine, 133: 153-161. |

邵桐, 苗晓燕, 周志祥, 等. 2017. 我国大气环境健康基准目标污染物筛选方法及候选清单研究[J]. 环境化学, 36: 2386-2397. |

Tsurusaki S, Tsuchiya Y, Koumura T, et al. 2019. Hepatic ferroptosis plays an important role as the trigger for initiating inflammation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis[J]. Cell Death Disease, 10: 449. |

Wang C, Chen R, Shi M, et al. 2018a. Possible mediation by methylation in acute inflammation following personal exposure to fine particulate air pollution[J]. American Journal of Epidemiology, 187: 484-493. |

Wang Y, Tang M. 2019. PM2.5 induces ferroptosis in human endothelial cells through iron overload and redox imbalance[J]. Environmental Pollution, 254: 112937. |

Wang Y, Xiong L, Wu T, et al. 2018b. Analysis of differentially changed gene expression in EA.hy926 human endothelial cell after exposure of fine particulate matter on the basis of microarray profile[J]. Ecotoxicology Environmental Safety, 159: 213-220. |

Xu M Y, Tao J, Yang Y D, et al. 2020. Ferroptosis involves in intestinal epithelial cell death in ulcerative colitis[J]. Cell Death & Disease, 11. |

Yamato H, Hori H, Tanaka I, et al. 1994. Retention and clearance of inhaled ceramic fibres in rat lungs and development of a dissolution model[J]. Occup Environmental Medicine, 51: 275-80. |

Yang M, Chen P, Liu J, et al. 2019. Clockophagy is a novel selective autophagy process favoring ferroptosis[J]. Science Advance, 5: 2238. |

Yang W S, Kim K J, Gaschler M M, et al. 2016a. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113: 4966-4975. |

Yang W S, Stockwell B R. 2016b. Ferroptosis: Death by lipid peroxidation[J]. Trends Cell Biology, 26: 165-176. |

Zhou H, Li F, Niu J Y, et al. 2019. Ferroptosis was involved in the oleic acid-induced acute lung injury in mice[J]. Acta Physiologica Sinica, 71: 689-697. |

Zhu X M, Wang Q, Xing W W, et al. 2018. PM2.5 induces autophagy-mediated cell death via NOS2 signaling in human bronchial epithelium cells[J]. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 14: 557-564. |

Zhu Z, Chen X, Sun J, et al. 2019. Inhibition of nuclear thioredoxin aggregation attenuates PM2.5-induced NF-kappaB activation and pro-inflammatory responses[J]. Free Radic Biology Medicine, 130: 206-214. |

2021, Vol. 41

2021, Vol. 41