2. 暨南大学环境学院, 广州 510632

2. School of Environment, Jinan University, Guangzhou 510632

垃圾渗滤液是一种成分复杂、毒性大、难处理的高浓度有害废水.渗滤液中不仅含有毒有害的无机物和有机物(如氨、重金属和脂肪酸类物质), 而且还含难降解、致癌和致突变的毒性物质(如苯胺类化合物、酚类和酯类化合物等)(Ghosh et al., 2017;Naveen et al., 2017);近年来有研究表明, 这类物质即使在毫克乃至纳克水平仍会对生物产生毒性效应(索俊昌等, 2015).因此, 垃圾渗滤液须经工艺处理达到排放标准后方可排放, 但在现有的渗滤液排放标准中, 尚未将一些潜在的致畸、致突变的毒性物质(如酚类化合物和酯类化合物)列为监控指标.此外, 排放液中的毒性物质是否得到有效去除、对生物体的毒性情况如何尚不清楚.因此, 开展有关渗滤液排放液对环境水体及周边生物的潜在毒性效应的评估研究, 对完善垃圾渗滤液处理技术具有重要意义.

目前, 关于垃圾渗滤液毒性的研究主要从生物水平和细胞水平进行, 其毒性评估所选用的生物材料主要包括胚胎(Li et al., 2017a;Baderna et al., 2019)、水生生物(Meng et al., 2017)、植物(Zhang et al., 2014;Yang et al., 2017)及细胞等(Alimba et al., 2016;Lecomte et al., 2017).人源肝癌细胞(HepG2)通常在体外评估中起重要作用(Ghosh et al., 2014a), 主要是由于抗氧化剂和细胞色素P450(CYP)1A1的表达可以被饮食和非饮食因素抑制(Henkler et al., 2012), 且HepG2细胞可以将假阳的可能性降至最低(Van et al., 2014), 故将HepG2细胞作为哺乳动物细胞中体外微核实验、体外致突变和致畸变实验的重要研究对象.在第五届国际遗传毒性测试研讨会上, 研究人员提出人类p53感受态细胞(如HepG2细胞)可作为评估遗传毒性的良好模型(Pfuhler et al., 2011).因此, 本研究选用HepG2细胞作为体外模型, 评估经工艺处理前后的垃圾渗滤液的细胞毒性和遗传毒性.

有研究表明, 未经工艺处理的垃圾渗滤液会严重威胁生态环境, 如抑制微生物的生长(Gong et al., 2016;de Oliveira et al., 2016);此外, 垃圾渗滤液中的毒性物质可通过食物链的富集和传递进入生物体内(Toufexi et al., 2013;Huang et al., 2017), 从而严重影响着人类健康和生态系统的稳定, 故需完善垃圾渗滤液处理工艺以减少排放液对周边生态的影响.硝化反硝化(SND)+超滤(UF)+纳滤(NF)或反渗透(RO)处理工艺对污水中毒性物质的去除率高(Oumar et al., 2016;Dai et al., 2015), 因此, 被广泛用于城市填埋场的垃圾渗滤液处理工艺中.

目前, 鲜有研究对经工艺处理后出水清液及各处理阶段渗滤液的毒性进行体外评估(Baderna et al., 2019).程蓉等对渗滤液经工艺处理前后作用于HepG2细胞的细胞毒性和遗传毒性变化进行了报道(Cheng et al., 2017), 恰巧细胞凋亡和细胞周期是将细胞毒性和遗传毒性完美联系起来的媒介, 可揭露毒性物质对细胞的作用机制及毒性状况(Noureddine et al., 2017).细胞毒性常反映样品对细胞活力的影响, 细胞活力的变化可大体反映出细胞凋亡情况, 而细胞凋亡又常伴随氧化损伤和细胞周期的变化(Feng et al., 2016), 细胞周期的变化与细胞内染色体的丢失或畸变紧密相关.目前, 关于垃圾渗滤液经工艺处理前后的细胞毒性和遗传毒性的机理和凋亡情况尚未见文献进行报道, 故本文将采用HepG2细胞对经工艺处理前后垃圾渗滤液的凋亡路径进行深入研究.

本文研究经SND/UF/RO工艺处理前后垃圾渗滤液的细胞毒性和遗传毒性的变化.通过MTT实验分析垃圾渗滤液的细胞毒性, 进一步探究经工艺处理前后的垃圾渗滤液对细胞的氧化系统、细胞周期和细胞凋亡的影响, 来研究渗滤液对HepG2细胞的毒性作用机制及评估渗滤液的毒性减量情况, 并结合微核实验和彗星实验评估经工艺处理前后渗滤液遗传毒性的变化.

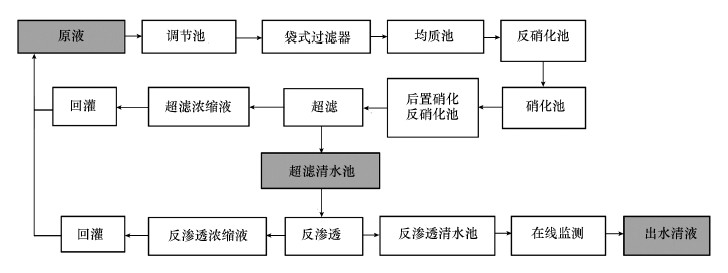

2 材料与方法(Materials and methods) 2.1 垃圾渗滤液的处理工艺及样品采集广州市兴丰垃圾填埋场已经运行了18 a, 每天的垃圾处理量约9000 t, 占全市垃圾日处理量的60%, 总量超过全市垃圾处理量的75%.目前兴丰填埋场采用的处理工艺是“预处理+生化处理+膜处理技术”, 处理工艺流程见图 1, 其中, 加粗字体且背景为灰色的区域表示本研究所采集的3种水样, 依次为渗滤液原液、超滤清液和出水清液, 分别储存在棕色玻璃瓶中并于4 ℃冰箱密封放置, 在短期内对水样进行水质参数测定.

|

| 图 1 兴丰垃圾填埋场渗滤液的处理工艺流程 Fig. 1 The technological treatment processeses of landfill leachate in Xingfeng |

pH和浊度值分别采用pHs-3C酸度计和2100Q(HACH)浊度仪进行测定.氨氮的测定主要采用纳氏试剂分光光度法, COD的测定采用快速消解分光光度法, 这两个参数均可在HACH-DR3900+DRB200型多参数水质测定仪上进行测定.

2.3 细胞毒性试验 2.3.1 细胞培养HepG2细胞由暨南大学医学院赠予, 细胞于37 ℃、5%CO2培养箱培养, 待贴壁长满时弃去旧培养基, 用磷酸盐缓冲液(PBS)洗涤细胞2遍, 加入1 mL胰酶后放入培养箱消化2 min, 取出加入1 mL新鲜培养基终止消化并将贴壁细胞吹入培养基中;然后将细胞悬浮液转移至15 mL无菌离心管中, 设置离心转速为800 r · min-1, 离心5 min, 弃上清液, 加入1 mL新鲜培养基重悬后转移至洁净无菌的培养瓶中, 补加3 mL新鲜培养基后放入CO2培养箱中, 隔天即可传代;步骤重复上述即可, 细胞一般优化到第4代用于实验效果最佳.

2.3.2 细胞毒性实验细胞毒性的测定常采用MTT实验, 其原理为活细胞内线粒体上的琥珀酸脱氢酶能使外源性MTT还原成水不溶性的蓝紫色结晶物甲臜并沉积在细胞中, 死细胞不具备该功能, MTT法测定细胞活力的方法是基于文献(Li et al., 2017;Cheng et al., 2017)并进行了微小修改.将HepG2细胞接种到96孔板(1×104 cells · mL-1)中培养24 h后, 弃培养基, 将细胞暴露于系列浓度(2.5%、5%、10%、15%、20%、25%、30%, V/V)的3种渗滤液水样中.染毒24 h后, 弃培养基, 每孔加入100 μL新鲜培养基和10 μL MTT(5 mg · mL-1), 继续孵育4 h后, 各孔加入100 μL二甲基亚砜将蓝紫色结晶物甲臜溶解并在490 nm处测吸光度, 根据吸光度计算细胞的存活率.

2.4 流式细胞术 2.4.1 细胞凋亡及细胞周期实验待HepG2细胞优化至最佳状态后将其接种至六孔板中, 每孔2 mL(1.0×105 cell · mL-1), 培养24 h后, 用MTT实验筛选后采用系列浓度的3种水样进行染毒24 h, 收集细胞备用.细胞凋亡(PI染液, Annexin V-FITC, 双染色法)和细胞周期(PI, 单染色)是通过流式细胞分析仪(Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA, USA)来分析细胞凋亡情况及细胞周期分布状况.

2.4.2 活性氧(ROS)的测定实验待HepG2细胞优化至最佳状态后将其接种至六孔板中, 每孔2 mL(1.0×105 cell · mL-1), 培养24 h后, 用3种水样(浓度同细胞凋亡实验)进行染毒6 h (Dos et al., 2018);然后收集细胞并离心(800 r · min-1, 5 min), 用200 μL 2, 7 -二氯二氢荧光素二醋酸盐(DCFH-DA)处理, 避光孵育20 min, 加入500 μL不含血清的培养基混匀, 800 r · min-1离心5 min, 弃上清液, 加入200 μL不含血清的培养基, 混匀, 上机测定荧光强度, 并计算实验组与对照组的相对荧光强度.

2.5 遗传毒性试验 2.5.1 微核实验微核实验根据Fenech等采用的体外微核试验方法并进行了微小修改(Nersesyan et al., 2016).实验步骤如下:染毒步骤同细胞凋亡实验, 染毒培养24 h后弃旧培养基, PBS洗涤两遍, 向各孔加2 mL新鲜培养基及Cyt-B储备液(2 μL, 6 mg · mL-1)后继续培养24 h, 同凋亡实验收集细胞(培养基中的悬浮细胞一并收集).将收集的细胞沉淀用1 mL新鲜培养基重悬后, 缓慢加入10 mL预冷氯化钾低渗液, 静置低渗2 min后, 再加5 mL预冷固定液并轻振离心管数次后离心(800 r · min-1, 5 min), 弃上清液, 重复操作加预冷固定液步骤2次后, 去上清液并预留100 μL固定液, 将细胞沉淀混合均匀.将细胞悬浮液滴在洁净的玻片上并做记号, 自然晾干后, 用Giemsa染液染色10 min, 然后将玻片在自来水下轻轻冲洗至玻片略呈微红色, 自然晾干后放于玻片盒中低温保存以备后续观察拍片.

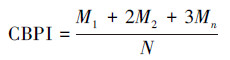

在光学显微镜中, 计算每个样品中1000个双核细胞(BNC)中含有的微核(MN)数, 同时计数1000个细胞中含有的单核细胞数、双核细胞数及多核细胞数, 然后计算出胞质阻断增殖指数(CBPI)和复制指数(RI), 计算公式如下:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

式中, M1、M2和Mn分别为单核细胞数、双核细胞数及多核细胞数, 下标T和C分别表示实验组和对照组, N为总细胞数(Wang et al., 2016).

2.5.2 单细胞凝胶电泳实验彗星实验被广泛用于评估环境污染物的遗传毒性(Bortolotto et al., 2009).将HepG2细胞以105 cell · mL-1的细胞密度接种在六孔板中培养24 h后, 选用5%渗滤液原液和30%出水清液对细胞进行染毒, 同时设置对照组(仅含空白培养基).染毒24 h后, 收集细胞, 取10 μL细胞悬液添加到含75 μL 0.7%低熔点琼脂糖凝胶上, 再铺上一层含0.5%正常熔点琼脂糖, 置于冰上避光保存20 min待凝胶凝固后, 将玻片转移至在预冷裂解缓冲液(2.5 mol · L-1 NaCl, 100 mmol · L-1 EDTA, 10 mmol · L-1 Tris-HCl, 1%Triton X-100, pH=10)中裂解1 h.接着将载玻片置于预冷电泳缓冲液(1 mmol · L-1EDTA, 300 mmol · L-1 NaOH, pH 13)中进行解旋1 h后, 在相同的缓冲溶液中于25 V电压下电泳30 min, 再用Tris-HCl缓冲液(0.4 mol · L-1, pH 7.5)中和3次, 每次10 min, 在室温下待其干燥后取40 μL PI进行染色.于荧光显微镜(Leica DM6000)观察彗星图像, 随机选择50个细胞并通过彗星图像分析软件(CASP)对DNA拖尾百分比(拖尾DNA占比)进行分析(Widziewicz et al., 2012a;Li et al., 2017).

2.6 数据分析所有实验数据均以重复性实验的平均值±标准偏差来表示, 各组实验均平行3次(n=3).MTT实验、ROS水平测定、凋亡实验、细胞周期、微核实验和彗星实验均采用SPSS 25.0结合方差分析(ANOVA)对实验组与对照组间的统计学差异进行分析(Bryman et al., 1999), p < 0.05被认为具有统计学意义.

3 结果与分析(Results and analysis) 3.1 渗滤液处理前后水质指标分析广州市兴丰垃圾填埋场中渗滤液原液、超滤清液、出水清液的水质分析结果见表 1.由表可知, 渗滤液原液经生化处理和超滤处理后, 超滤清液中COD、氨氮和浊度的去除率分别为86.45%、99.46%和99.69%, 超滤清液进一步通过反渗透技术处理后, 可将水样中残留的部分有机物、细菌及胶体粒子截留, 出水清液中COD、氨氮和浊度的去除率依次为99.38%、99.90%和99.76%, 表明出水清液中有机污染物基本已去除, 出水清液的水质指标均达到了排放标准.

| 表 1 渗滤液3种水样的水质指标 Table 1 Water quality indicators of three samples of leachate |

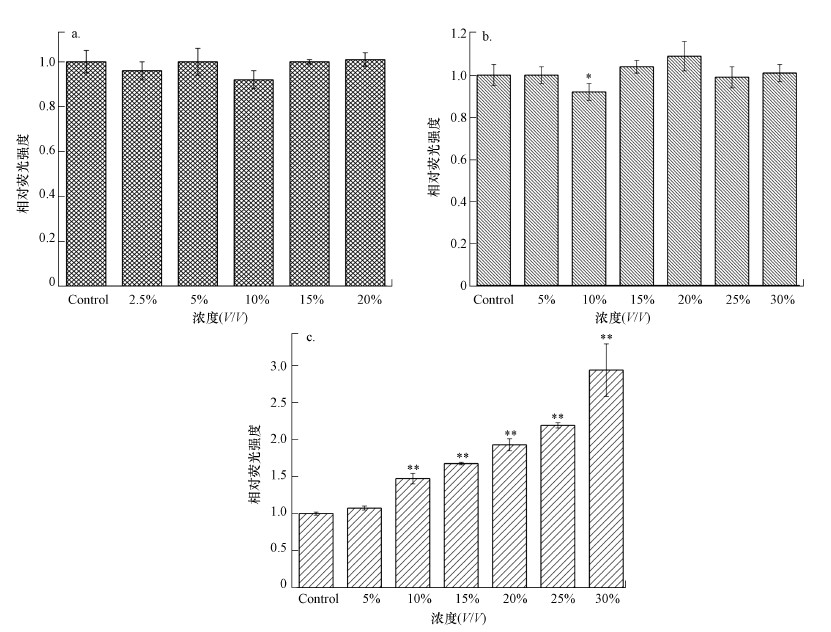

将HepG2细胞暴露在3种渗滤液水样中, 其细胞存活情况见图 2.由图可知, 暴露在渗滤液原液和经工艺处理后的出水清液间细胞活力存在着显著性差异, 尤其当暴露在浓度为30%(V/V)的水样中, 暴露在渗滤液原液和经SND/UF/RO工艺处理后的出水清液中, 细胞存活率分别为38.3%和88.4%.经SND/UF/RO处理后在浓度为10%时细胞活力表现出明显上升趋势, 细胞存活率由45.4%上升至102%, 说明SND/UF/RO工艺对垃圾渗滤液的毒性去除率较高, 但出水清液仍表现出微弱的细胞毒性.

|

| 图 2 暴露在3种水样24 h后细胞毒性的变化 (数值表示为平均值±标准差, n =3;*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01时, 表示对照组与实验组间差异显著, 下同) Fig. 2 Cytotoxicity changes in three samples after 24 h (Values represent mean±SD, n=3. "*" and "**" represent difference between control group and treatments groups at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, respectively, the same below) |

HepG2细胞暴露在3个水样24 h后的凋亡结果如表 2所示.由表可知, 渗滤液原液(2.5%、5%、10%、15%、20%, V/V)能诱导HepG2细胞发生明显的凋亡现象, 凋亡率为2.79%~28.26%, 且随着暴露浓度的增加细胞凋亡现象愈加明显, 当暴露浓度为10%时细胞凋亡率达到最大.当细胞暴露在系列浓度的出水清液(5%、10%、15%、20%、25%、30%, V/V)中时, 细胞凋亡率均低于5%, 表明出水清液不能明显诱导细胞凋亡.该结果与MTT测定结果一致, 这也证实SND/UF/RO工艺对垃圾渗滤液的毒性去除率较高.

| 表 2 SND/UF/RO工艺处理前后3种水样在不同浓度下对HepG2细胞凋亡率的影响 Table 2 The apoptosis rate of HepG2 cells exposed landfill leachate before and after SND/UF/RO treatment at different concentrations |

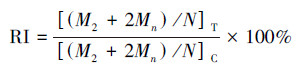

从图 3可以看出, 当暴露于SND/UF/RO工艺处理后的出水清液时, HepG2细胞内ROS的水平随暴露浓度的增加逐渐增加, 当暴露浓度为30%时ROS水平相比对照组增加了约1.7倍(p < 0.05);而暴露在渗滤液原液和超滤清液中细胞内ROS水平并未表现出明显变化.

|

| 图 3 不同渗滤液水样处理后的活性氧含量变化 (a.原液, b.超滤清液, c.出水清液) Fig. 3 The changes of reactive oxygen species in HepG2 cells with different leachate samples after treatment (a.untreated leachate, b.SND/UF tdreated leachate, c.effluent) |

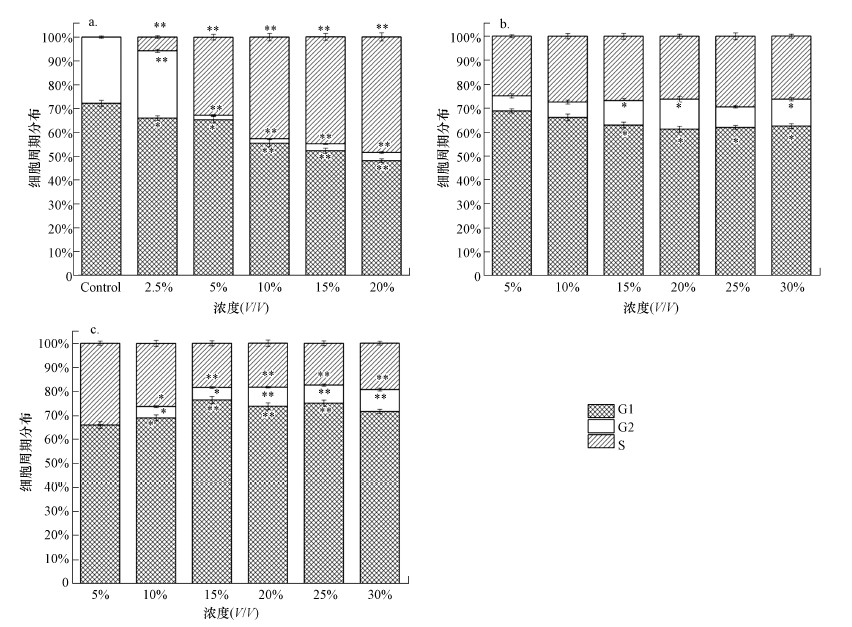

垃圾渗滤液经SND/UF/RO处理前后的3种水样对细胞周期的影响如图 4所示.从图 4a可以看出, 渗滤液原液可将细胞阻滞在S期, 且随着暴露浓度的增加阻滞在S期的细胞百分比可高达48.5%, 表明渗滤液原液会影响DNA合成并抑制细胞增殖(p < 0.05).而渗滤液经SND/UF工艺处理后, 超滤清液对HepG2细胞有微弱阻滞作用(图 4b).经SND/UF/RO工艺处理后的出水清液, 其对细胞仍有微弱的阻滞作用并可将细胞阻滞在G2期, 且随着暴露浓度的增加滞留在G2期的细胞百分比由0增加至9.15%(图 4c).

|

| 图 4 原液(a)、超滤清液(b)及出水清液(c)处理24 h后的细胞周期分布 Fig. 4 Cell cycle distribution of HepG2 cell when exposed to untreated leachate(a), SND/UF treated leachate(b) and the effluent(c) |

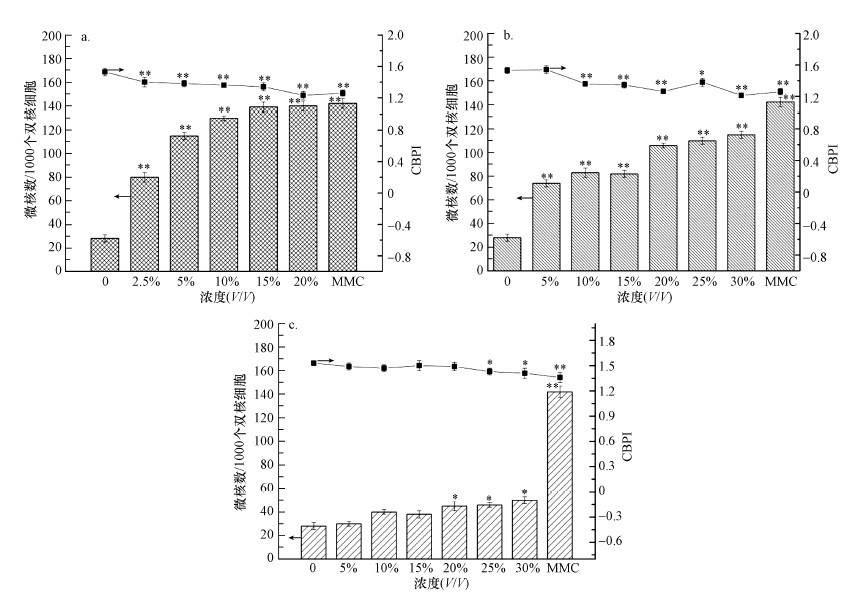

暴露于系列浓度的渗滤液原液和经工艺处理后的水样中, HepG2细胞内的微核数(MN)和胞质分裂增殖指数(CBPI)变化情况如图 5所示.从图 5a可以看出, 渗滤液原液能诱导细胞内微核数的产生, 与阴性对照组相比差异显著(p < 0.01);暴露在渗滤液原液中的HepG2细胞, 随着暴露浓度的增加微核数也逐渐增加, 与阴性对照组相比约增加了2.9~5.1倍.然而暴露在系列浓度的超滤清液和出水清液中细胞内的微核数与阴性对照组相比几乎无显著性差异(图 5b和5c).表 3所示为暴露在渗滤液原液和经工艺处理后渗滤液中HepG2细胞的复制指数(RI).由表可知, 当暴露在渗滤液原液时, RI值和CBPI值在浓度为2.5%时有明显降低趋势(p < 0.01), 且与浓度呈负相关;而暴露在出水清液中细胞的CBPI和RI值变化较小(p < 0.05), 这与细胞毒性实验的结果一致.

|

| 图 5 细胞暴露水样24 h后微核试验结果 (a.原液, b.超滤清液, c.出水清液) Fig. 5 Results of micronucleus test exposure to three samples for 24 h (a.untreated leachate, b.SND/UF treated leachate, c.effluent) |

| 表 3 微核实验复制因子RI值 Table 3 Values of replication index (RI) from micronucleus assay |

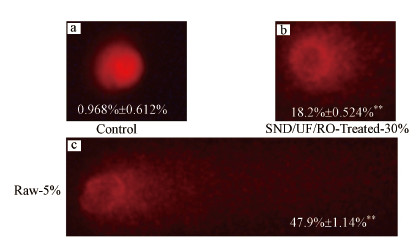

同时, 通过碱性单细胞凝胶电泳实验分析渗滤液原液和出水清液对细胞内的DNA损伤情况, 结果如图 6所示.空白对照的DNA图像为圆形红色荧光头, 表明NDA无损坏或破损;在实验组中细胞内DNA有明显的破坏甚至断裂现象.浓度为30%出水清液和5%渗滤液原液对HepG2细胞有明显的遗传毒性, 暴露于出水清液的细胞内尾部DNA含量为18.2%, 而暴露在渗滤液原液的细胞内尾部DNA百分比为47.9%, 属于DNA的高度损伤.

|

| 图 6 HepG2细胞暴露在渗滤液原液和出水清液中24 h后的彗星图像 (a.对照组, b.30%SND/UF/RO处理后的出水清液, c.5%渗滤液原液;图中数据表示尾部DNA百分比) Fig. 6 Representative images of comets of different classes of genotoxic effects on HepG2 cells after 24 h (a.control, b.30% SND/UF/RO treated leachate, c.5% untreated leachate; The data in each figure represents the percentage of tail DNA) |

垃圾渗滤液的处理是目前环境治理的关键问题, 主要是由于垃圾渗滤液中含有大量污染物威胁着生态环境的正常运行, 而垃圾渗滤液未经处理达标均不得直接排放到自然环境中(Gajski et al., 2012).经SND/UF/RO处理后出水清液的基础理化指标均低于排放标准所规定的限值(GB 16889—2008), 满足排放标准且与之前文献(Kjeldsen et al., 2002)报道的结果基本一致.在本研究中, 垃圾渗滤液经SND/UF/RO工艺处理后, 虽基础理化指标符合允许排放的标准, 但出水清液中可能仍存在痕量的环境激素(Cheng et al., 2017), 因此, 对生态的影响和威胁是不容忽视的(Jaishankar et al., 2014;Guo et al., 2017).

近年来, 对于垃圾渗滤液的毒性评估常从生物个体或细胞水平进行研究(Alimba et al., 2016;Budi et al., 2016), 反映垃圾渗滤液对周边水体、生态环境及人类的影响.因此, 本研究探讨了渗滤液在工艺处理过程中的毒性降低情况尤其是出水清液的毒性, 通过毒性实验来评估水样的细胞毒性和遗传毒性(Toufexi et al., 2013).垃圾渗滤液诱导DNA损伤的机制可能与其增强异种生物产生的氧化应激的能力有关(Bakare et al., 2012), 有研究报道了垃圾渗滤液会被吸收到细胞内而改变细胞内外的pH和环境从而破坏DNA链状(Bakare et al., 2007;Garaj-Vrhovac et al., 2013).在本研究中, 渗滤液原液浓度超过5%时细胞活力均低于50%, 而彗星实验需确保细胞存活率在50%以上(Wang et al., 2016)来满足所需的细胞数;选择30%出水清液主要是因为仅在该浓度下对HepG2细胞有微弱的细胞毒性, 故考察该浓度下的出水清液对DNA的损伤情况为遗传毒性评估提供有力依据, 也与MTT实验相呼应.彗星实验结果表明, 暴露在30%出水清液中细胞内DNA出现明显的彗星拖尾现象, 这意味着出水清液仍具有遗传毒性会损伤HepG2细胞内的DNA.而DNA损伤表现在对HepG2细胞中染色体的畸变和丢失, 微核实验表明出水清液的遗传毒性与渗滤液原液相比已显著降低, 主要表现为暴露在出水清液的HepG2细胞中的微核数、细胞分裂增殖指数和复制指数均与阴性对照组间的差异急剧缩小, 结合彗星实验也佐证出水清液仍具有出较弱的遗传毒性.在本研究中, 垃圾渗滤液引起的遗传毒性效力与部分文献(Baderna et al., 2011;Ghosh et al., 2014)报道的基本一致.

染色体丢失及DNA损伤与细胞周期的变化有着紧密的关系, 细胞周期是当细胞分裂形成子细胞直到下一个细胞分裂成子细胞时发生的过程(金艳书等, 2006).细胞周期中两个最关键的阶段是G1期~S期和G2期~M期, 这两个阶段细胞内活性分子水平变化复杂且易受外部环境影响(Dimitris et al., 2014).本研究中细胞周期实验表明垃圾渗滤液原液诱导细胞停滞在S期, 意味着渗滤液原液会阻止细胞内染色体的合成并减慢细胞的增殖(Lazari et al., 2017);而出水清液将细胞阻滞在G2期使细胞内核苷酸在合成过程受阻并影响着染色体的形成.细胞周期异常表明在细胞周期过程中出现了DNA损伤和基因组不稳定(Dimitris et al., 2014), 有研究报道了细胞被阻滞在G2/M期的异常结果可能与微核数的增加有关(Muthusamy et al., 2018).

细胞周期阻滞和染色体异常情况反映出HepG2细胞存在凋亡和氧化损伤现象, 而凋亡是指受基因控制以维持体内稳态的细胞有序死亡, 这与细胞坏死不同, 细胞凋亡不是病理条件下的自体损伤和被动过程, 而是涉及一系列基因的激活、表达和调控以更好地适应新环境的主动过程(Wyllie et al., 1980).在本研究中, 垃圾渗滤液原液能明显地诱导HepG2细胞发生凋亡, 尤其当暴露在10%渗滤液原液中时凋亡率达到最大值;经SND/UF/RO工艺处理后, 出水清液对HepG2细胞未能表现明显的凋亡现象, 这表明渗滤液中的毒性物质已大量去除.此外, 有研究表明ROS的产生可能导致额外的基因组损伤, 因为氧化应激是导致基因组损伤的外源物质作用的主要生化机制之一(Santos et al., 2007; Widziewicz et al., 2012b).本研究中暴露在出水清液中细胞内的ROS水平明显增加, 而暴露在渗滤液原液和经SND/UF处理的超滤清液中时细胞内的ROS水平无明显变化, 这是因为ROS属于早期指标, 触发比凋亡和DNA损伤都要早, ROS变化只在凋亡早期之前出现(Mashayekhi et al., 2014).Nisar等(2015)发现敌草快除草剂在低、中浓度时对SH-SY5Y能产生较多的活性氧自由基, 而在高浓度下ROS水平与对照组基本一致, 主要由于高浓度的除草剂会使细胞坏死导致ROS水平基本不变, 这一结果与渗滤液原液和超滤清液的测定结果相近.

细胞凋亡和氧化损伤从侧面反映出HepG2细胞的细胞活力变化, 而MTT实验也是一种可靠的体外细胞毒性研究方法, 能将细胞死亡的可能原因与线粒体功能改变或线粒体损伤关联起来(Lone et al., 2017;Viola et al., 2018).此外, MTT实验也为后续实验对3种水样的浓度选择进行了合理的筛选;MTT实验结果表明, 出水清液对HepG2细胞表现出较弱的细胞毒性, 而渗滤液原液由于含有高浓度的难降解有机污染物和高浓度的无机盐而影响细胞的生长环境并破坏相应的酶活性而引发高死亡率.

5 结论(Conclusions)垃圾渗滤液原液因为有极高的细胞毒性和遗传毒性, 可诱导HepG2细胞向着凋亡路径发生;而经SND/UF/RO工艺处理后, 出水清液的细胞毒性和遗传毒性急剧降低, 但仍会损伤HepG2细胞的氧化系统及对细胞内的DNA有微弱损伤.因此, 通过系列毒性试验来评估渗滤液经SND/UF/RO工艺处理前后的毒性, 揭露渗滤液中的毒性物质对细胞的作用机制主要从氧化损伤、细胞凋亡向着染色体异常及DNA损伤方向进行.此外, 经SND/UF/RO工艺处理的渗滤液虽可达排放标准, 但出水清液仍显示出较弱的细胞毒性和遗传毒性, 意味着需完善处理技术以降低对生态环境的潜在风险.

Alimba C G, Gandhi D, Sivanesan S, et al. 2016. Chemical characterization of simulated landfill soil leachates from Nigeria and India and their cytotoxicity and DNA damage inductions on three human cell lines[J]. Chemosphere, 164: 469-479. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.08.093 |

Baderna D, Caloni F, Benfenati E. 2019. Investigating landfill leachate toxicity in vitro:A review of cell models and endpoints[J]. Environment International, 122: 21-30. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2018.11.024 |

Baderna D, Maggioni S, Boriani E, et al. 2011. A combined approach to investigate the toxicity of an industrial landfill's leachate:Chemical analyses, risk assessment and in vitro assays[J]. Environmental Research, 111(4): 603-613. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2011.01.015 |

Bakare A A, Pandey A K, Bajpayee M, et al. 2007. DNA damage induced in human peripheral blood lymphocytes by industrial solid waste and municipal sludge leachates[J]. Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis, 48(1): 30-37. DOI:10.1002/em.20272 |

Bakare A A, Patel S, Pandey A K, et al. 2012. DNA and oxidative damage induced in somatic organs and tissues of mouse by municipal sludge leachate[J]. Toxicology and Industrial Health, 28(7): 614-623. DOI:10.1177/0748233711420466 |

Bortolotto T, Bertoldo J B, da Silveira F Z, et al. 2009. Evaluation of the toxic and genotoxic potential of landfill leachates using bioassays[J]. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 28(2): 288-293. DOI:10.1016/j.etap.2009.05.007 |

Bryman A, Cramer D. 1999. Quantitative data analysis for social scientists[J]. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 21(3): 397-400. |

Budi S, Suliasih B A, Othman M S, et al. 2016. Toxicity identification evaluation of landfill leachate using fish, prawn and seed plant[J]. Waste Management, 55: 231-237. DOI:10.1016/j.wasman.2015.09.022 |

Cheng R, Zhao L, Yin P. 2017. Genotoxic effects of old landfill leachate on HepG2 cells after nitration/ultrafiltration/reverse osmosis membrane treatment process[J]. Journal of Applied Toxicology, 37(12): 1455-1463. DOI:10.1002/jat.3490 |

Dai Y, Song Y, Gao H, et al. 2015. Bibliometric analysis of research progress in membrane water treatment technology from 1985 to 2013[J]. Scientometrics, 105(1): 577-591. DOI:10.1007/s11192-015-1669-4 |

de Oliveira, Luciana F, Santos C, et al. 2016. Biomarkers in the freshwater bivalve Corbicula fluminea confined downstream a domestic landfill leachate discharge[J]. Environmental Science & Pollution Research, 23(14): 1-12. |

Dimitris S, Souliotis V L, Margarita B, et al.2014.Benzo[a]pyrene-induced cell cycle arrest in HepG2 cells is associated with delayed induction of mitotic instability[J].Mutation Research, 769(4): 59-68

|

Dos Santos Rodrigues B, de Avila R I, Benfica P L, et al. 2018. 4-Fluorobenzaldehyde limonene-based thiosemicarbazone induces apoptosis in PC-3 human prostate cancer cells[J]. Life Science, 203: 141-149. DOI:10.1016/j.lfs.2018.04.024 |

Feng C P, Tang H M, Huang S, et al. 2016. Evaluation of the effects of the water-soluble total flavonoids from Isodon lophanthoides var.gerardianus (Benth.) H.Hara on apoptosis in HepG2 cell:Investigation of the most relevant mechanisms[J]. Journal Ethnopharmacol, 188: 70-79. DOI:10.1016/j.jep.2016.04.042 |

Gajski G, Oreščanin V, Garaj-Vrhovac V. 2012. Chemical composition and genotoxicity assessment of sanitary landfill leachate from Rovinj, Croatia[J]. Ecotoxicology & Environmental Safety, 78(2): 253-259. |

Garaj-Vrhovac, Oreščanin V, Petra, et al. 2013. Toxicological characterization of the landfill leachate prior/after chemical and electrochemical treatment:A study on human and plant cells[J]. Chemosphere, 93(6): 939-945. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.05.059 |

Ghosh P, Das M T, Thakur I S. 2014. Mammalian cell line-based bioassays for toxicological evaluation of landfill leachate treated by Pseudomonas sp.ISTDF1[J]. Environmental Science & Pollution Research International, 21(13): 8084-8094. |

Ghosh P, Swati T, Indu S. 2014. Enhanced removal of COD and color from landfill leachate in a sequential bioreactor[J]. Bioresource Technology, 170(5): 10-19. |

Ghosh P, Indu S, Kaushik A. 2017. Bioassays for toxicological risk assessment of landfill leachate:A review[J]. Ecotoxicology & Environmental Safety, 141: 259. |

Gong Y, Tian H, Dong Y, et al. 2016. Thyroid disruption in male goldfish (Carassius auratus) exposed to leachate from a municipal waste treatment plant:Assessment combining chemical analysis and in vivo bioassay[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 554-555: 64-72. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.02.188 |

Guo Y, Wu X Y, Xiong W, et al. 2017. Prevention and treatment of lead poisoning in children-A review with recent updates[J]. Chinese Journal of Child Health Care, 4: 378-381. |

Henkler F, Stolpmann K, Luch A. 2012. Exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons:bulky DNA adducts and cellular responses[J]. Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology, 101: 107-103. |

Huang Q, Chen Y, Lin L, et al. 2017. Different effects of bisphenol a and its halogenated derivatives on the reproduction and development of Oryzias melastigma under environmentally relevant doses[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 595: 752-758. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.263 |

Jaishankar M, Tseten T, Anbalagan N, et al. 2014. Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals[J]. Interdisciplinary Toxicology, 7(2): 60-72. DOI:10.2478/intox-2014-0009 |

金艳书, 吴学敏, 娄金丽. 2006. 苦参碱对人肝癌细胞增殖、细胞周期及细胞凋亡的影响[J]. 中国临床康复, (3): 107-109. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1673-8225.2006.03.043 |

Kjeldsen P, Barlaz M A, Rooker A P, et al. 2002. Present and long-term composition of MSW landfill leachate:A review[J]. CRC Critical Reviews in Environmental Control, 32(4): 297-336. DOI:10.1080/10643380290813462 |

Lazari D, Alexiou G A, Markopoulos G S, et al. 2017. N-(p-coumaroyl) serotonin inhibits glioblastoma cells growth through triggering S-phase arrest and apoptosis[J]. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 132(3): 373-381. DOI:10.1007/s11060-017-2382-3 |

Lecomte S, Lelong M, Bourgine G, et al. 2017. Assessment of the potential activity of major dietary compounds as selective estrogen receptor modulators in two distinct cell models for proliferation and differentiation[J]. Toxicology & Applied Pharmacology, 325: 61-70. |

Li J, Niu A, Lu C, et al. 2017. A novel forward osmosis system in landfill leachate treatment for removing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and for direct fertigation[J]. Chemosphere, 168: 112-121. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.10.048 |

Li X, Yin P, Zhao L. 2017. Effects of individual and combined toxicity of bisphenol A, dibutyl phthalate and cadmium on oxidative stress and genotoxicity in HepG 2 cells[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 105: 73-81. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2017.03.054 |

Lone M I, Nabi A, Dar N J, et al. 2017. Toxicogenetic evaluation of dichlorophene in peripheral blood and in the cells of the immune system using molecular and flow cytometric approaches[J]. Chemosphere, 167: 520-529. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.08.131 |

Mashayekhi V, Eskandari M R, Kobarfard F, et al. 2014. Induction of mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) pore opening and ROS formation as a mechanism for methamphetamine-induced mitochondrial toxicity[J]. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Archives of Pharmacology, 387(1): 47-58. DOI:10.1007/s00210-013-0919-3 |

Meng S L, Qiu L P, Hu G D, et al. 2017. Effect of methomyl on sex steroid hormone and vitellogenin levels in serum of male tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and recovery pattern[J]. Environmental Toxicology, 32: 7. DOI:10.1002/tox.22207 |

Muthusamy S, Peng C, Ng J C. 2018. Genotoxicity evaluation of multi-component mixtures of polyaromatic hydrocarbons(PAHs), arsenic, cadmium, and lead using flow cytometry based micronucleus test in HepG2 cells[J]. Mutation Research, 827: 9-18. DOI:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2018.01.002 |

Naveen B P, Mahapatra D M, et al. 2017. Physico-chemical and biological characterization of urban municipal landfill leachate[J]. Environmental Pollution, 220: 1-12. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2016.09.002 |

Nersesyan A, Fenech M, Bolognesi C, et al. 2016. Use of the lymphocyte cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay in occupational biomonitoring of genome damage caused by in vivo exposure to chemical genotoxins:past, present and future[J]. Mutation Research, 770: 1-11. DOI:10.1016/j.mrrev.2016.05.003 |

Nisar R, Hanson P S, He L, et al. 2015. Diquat causes caspase-independent cell death in SH-SY5Y cells by production of ROS independently of mitochondria[J]. Archives of Toxicology, 89(10): 1811-1825. DOI:10.1007/s00204-015-1453-5 |

Noureddine H, Hage-Sleiman R, Wehbi B, et al. 2017. Chemical characterization and cytotoxic activity evaluation of Lebanese propolis[J]. Biomedicine Pharmacotherapy, 95: 298-307. DOI:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.067 |

Oumar D, Patrick D, Gerardo B, et al. 2016. Coupling biofiltration process and electrocoagulation using magnesium-based anode for the treatment of landfill leachate[J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 181: 477-483. |

Pfuhler S, Fellows M, Benthem J V, et al. 2011. In vitro genotoxicity test approaches with better predictivity:Summary of an IWGT workshop[J]. Mutation Research, 723(2): 101-107. DOI:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2011.03.013 |

Santos N A G D, Martins N M, Curti C, et al. 2007. Dimethylthiourea protects against mitochondrial oxidative damage induced by cisplatin in liver of rats[J]. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 170(3): 177-186. DOI:10.1016/j.cbi.2007.07.014 |

索俊昌.2015.渗滤液中酚类雌激素的去除及细胞毒性评价研究[D].广州: 暨南大学

|

Toufexi E, Tsarpali V, Efthimiou I, et al. 2013. Environmental and human risk assessment of landfill leachate:an integrated approach with the use of cytotoxic and genotoxic stress indices in mussel and human cells[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 260: 593-601. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.05.054 |

Van den Hof, van Herwijnen M, Brauers K, et al. 2014. Classification of hepatotoxicants using HepG2 cells:A proof of principle study[J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 27(3): 433-442. DOI:10.1021/tx4004165 |

Viola K S, Rodrigues E M, Tanomaru-Filho M, et al. 2018. Cytotoxicity of peracetic acid:evaluation of effects on metabolism, structure and cell death[J]. International Endodontic Journal, 51(Suppl 4): e264-e277. |

Wang G, Lu G, Yin P, et al. 2016. Genotoxicity assessment of membrane concentrates of landfill leachate treated with Fenton reagent and UV-Fenton reagent using human hepatoma cell line[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 307: 154-162. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.12.069 |

Widziewicz K, Kalka J, Skonieczna M, et al. 2012. The comet assay for the evaluation of genotoxic potential of landfill leachate[J]. Scientific World Journal, 2012(6): 435239. |

Wyllie A H, Kerr J F R, Currie A R. 1980. Cell death:The significance of apoptosis[J]. International Review of Cytology, 68(251): 251-306. |

Yang L, Sun T, Liu Y, et al. 2017. Photosynthesis of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) in response to landfill leachate contamination[J]. Chemosphere, 186: 743-748. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.08.056 |

Zhang Y, Habteselassie M Y, Resurreccion E P, et al. 2014. Evaluating removal of steroid estrogens by a model alga as a possible sustainability benefit of hypothetical integrated algae cultivation and wastewater treatment systems[J]. Acs Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 2(11): 2544-2553. |

2021, Vol. 41

2021, Vol. 41