海军舰艇官兵是一个特殊的群体。他们工作性质特殊,训练任务繁重,社会环境相对隔绝,容易出现心理压力[1],导致主观幸福感降低[2],影响工作绩效[3]。因此,关注舰艇官兵主观幸福感具有重要的现实意义。

主观幸福感通常是指个体根据自定的标准对其生活质量的总体评估,是衡量个体生活质量的综合性心理指标[4]。依恋、自尊、负性情绪都是其重要影响因素[5-8]。依恋是个体与生俱来的一种形成和保持亲密关系的倾向[9],其对主观幸福感的影响得到研究证实[10]。Brennan等[11]将成人依恋分为依恋回避和依恋焦虑两个维度,依恋焦虑的个体会怀疑自我价值,对亲密关系充满警惕[12]。研究发现依恋焦虑对主观幸福感具有显著负向预测作用[13-14]。自尊是个体对自我价值和自我接纳的总体感受,是对自我积极或消极的态度[15]30-31,它是成年人主观幸福感最强的预测因子之一[16]。负性情绪一般是指焦虑、抑郁等消极的情绪,是评估主观幸福感的重要指标[17]。

研究显示,不安全的依恋与更低的自尊水平有关[18],且依恋焦虑与个体的自尊水平呈显著负相关[19]。根据依恋的内部工作模式理论可知,依恋通过内部工作模式对个体心理状态产生影响,而自尊是内部工作模式的重要成分[20]。因此可以推测,自尊可能是依恋焦虑影响主观幸福感的一个中介变量[21]。依恋焦虑能显著正向预测焦虑、抑郁等负性情绪[22-24],而负性情绪与主观幸福感密切相关[25],提示负性情绪在依恋焦虑和主观幸福感之间可能起着中介作用。此外,自尊与负性情绪密切相关[26],纵向研究表明,低自尊预测焦虑和抑郁的水平随着时间的推移而增加,且焦虑和抑郁并不能预测自尊水平的下降[27-28]。这提示自尊可能是依恋焦虑对负性情绪影响的中介变量,依恋焦虑可以通过自尊影响负性情绪,从而进一步影响主观幸福感。

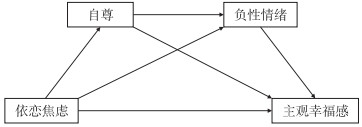

综上所述可知,自尊和负性情绪在依恋焦虑与主观幸福感之间发挥着重要作用,且自尊会影响负性情绪。因此本研究提出如下假设:自尊、负性情绪可能在依恋焦虑和主观幸福感之间起链式中介作用,假设模型见图 1。本研究聚焦海军舰艇官兵,通过问卷法对其依恋焦虑、自尊、负性情绪和主观幸福感进行测量,并在已有理论基础上利用结构方程模型探讨依恋焦虑影响主观幸福感的机制,以期为提升舰艇官兵的主观幸福感提供实证依据。

|

图 1 依恋焦虑、自尊、负性情绪和主观幸福感关系的假设模型 |

1 对象和方法 1.1 研究对象

采用G*Power3.1.9.2软件估计样本量,基于前人研究[29]设置参数,要达到90%以上的统计功效约需要88名被试。本研究采用便利抽样法抽取288名海军舰艇官兵进行问卷调查,回收有效问卷257份,回收有效率为89.24%。

1.2 调查工具 1.2.1 成人依恋量表采用Collins和Read[30]编制的成人依恋量表中的依恋焦虑维度测量官兵的依恋焦虑情况,依恋焦虑维度测量一个人担心被抛弃或不被喜爱的程度,量表采用5点计分。

1.2.2 自尊量表采用Rosenberg[15]305-307于1965年编制、汪向东等[31]1999年修订的自尊量表测量官兵的自尊水平。该量表共10个条目,采用Likert 4级评分,其中第3、5、8、9、10个条目为反向计分,总分为10~40分,得分越高表示自尊程度越高。

1.2.3 7项广泛性焦虑障碍量表(generalized anxiety disorder-7 items,GAD-7)[32]采用GAD-7测量官兵的焦虑水平。量表共7个条目,采用0~3级评分,要求报告过去2周受焦虑问题困扰的程度。GAD-7总分0~21分,其中0~5分为无焦虑、6~9分为轻度焦虑、10~14分为中度焦虑、15~21分为重度焦虑。

1.2.4 患者健康问卷抑郁自评量表(patient health questionnaire-9,PHQ-9)[33]采用PHQ-9测量官兵的抑郁水平。量表共9个条目,采用0~3级评分,要求报告过去2周受抑郁问题困扰的程度。PHQ-9总分0~27分,其中0~5分为无抑郁、6~9分为轻度抑郁、10~14分为中度抑郁、15~19分为重度抑郁、20~27分为极重度抑郁。

1.2.5 纽芬兰纪念大学幸福度量表(Memorial University of Newfoundland scale of happiness,MUNSH)采用MUNSH测量官兵的主观幸福感。MUNSH共有24个条目,包括正性情感(positive affect,PA)、负性情感(negative affect,NA)、正性情感体验(positive emotional experience,PE)、负性情感体验(negative emotional experience,NE)4个部分,总主观幸福感得分=PA得分-NA得分+PE得分-NE得分,得分范围为-24~24分,统计时常加上常数24。0~12分表明主观幸福感低,13~35分表明主观幸福感中等,36~48分表明主观幸福感高[34]。

1.3 统计学处理采用SPSS 22.0软件对数据进行录入与统计分析。数据以x±s表示,采用Pearson相关分析检验变量间的相关性;采用多元线性回归分析检验依恋焦虑、自尊和负性情绪对主观幸福感的预测性;采用Amos 24.0软件构建结构方程模型,检验自尊和负性情绪在依恋焦虑和主观幸福之间的中介效应。检验水准(α)为0.05。

2 结果 2.1 相关分析257名海军舰艇官兵的依恋焦虑得分为(1.91±0.76)分,自尊得分为(32.95±4.74)分,焦虑得分为(2.56±3.07)分,抑郁得分为(3.09±3.04)分,主观幸福感得分为(30.68±9.81)分。Pearson相关分析结果(表 1)显示,依恋焦虑、焦虑和抑郁得分两两互为正相关,自尊得分与主观幸福感得分呈正相关,其余变量之间互为负相关(均P<0.01)。

|

|

表 1 各变量的相关关系 |

2.2 多元线性回归分析

以主观幸福感为因变量,依恋焦虑、自尊、焦虑和抑郁为自变量进行分层回归分析,分层回归第一层放入依恋焦虑,第二层放入自尊,第三层放入焦虑和抑郁。第一层回归分析结果显示,依恋焦虑可单独预测主观幸福感的18.1%(F=56.54,P<0.01),依恋焦虑对主观幸福感具有负向预测作用(β=-5.47,P<0.01)。第二层回归分析结果显示,依恋焦虑和自尊可共同预测主观幸福感的24.9%(F=42.18,P<0.01),依恋焦虑对主观幸福感具有负向预测作用(β=-3.86,P<0.01),自尊对主观幸福感具有正向预测作用(β=0.60,P<0.01)。第三层回归分析结果显示,依恋焦虑、自尊、抑郁和焦虑可共同预测主观幸福感的42.4%(F=46.31,P<0.01),依恋焦虑对主观幸福感无预测作用(β=-1.28,P>0.05),自尊对主观幸福感具有正向预测作用(β=0.35,P<0.01),焦虑和抑郁均对主观幸福感具有负向预测作用(β=-0.74,P<0.01;β=-0.99,P<0.01)。

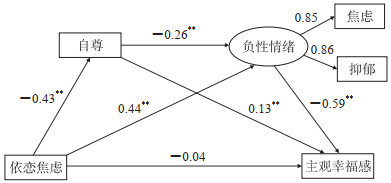

2.3 中介效应模型检验采用Amos 24.0软件构建以依恋焦虑为自变量,自尊、负性情绪为中介变量,主观幸福感为因变量的中介模型。模型各项拟合指数良好(χ2/df=0.170,P=0.844,拟合优度指数为0.999,调整拟合优度指数为0.996,规范拟合指数为0.999,相对拟合指数为0.997,比较拟合指数为1.000,近似误差均方根为0.000),中介路径如图 2所示。

|

图 2 自尊、焦虑在依恋焦虑对主观幸福感效应中的链式中介作用 路径线上的数据为标准化回归系数. **P<0.01. |

通过偏差校正的非参数百分位Bootstrap法(重复取样5 000次)对中介效应进行检验,计算95% CI。结果显示,自尊和负性情绪在依恋焦虑与主观幸福感之间的中介效应显著,效应值的95% CI均不包括0。中介效应具体通过3条路径产生:路径1为依恋焦虑→自尊→主观幸福感,自尊的中介效应显著,占总效应的13.4%;路径2为依恋焦虑→负性情绪→主观幸福感,负性情绪的中介效应显著,占总效应的61.0%;路径3为依恋焦虑→自尊→负性情绪→主观幸福感,自尊和负性情绪的链式中介效应显著,占总效应的15.9%。依恋焦虑对主观幸福感的直接效应不显著,这说明自尊、负性情绪在依恋焦虑对主观幸福感的影响中起完全链式中介作用。见表 2。

|

|

表 2 自尊、负性情绪在依恋焦虑和主观幸福感之间的中介效应分析 |

3 讨论

本研究结果表明,舰艇官兵的依恋焦虑可通过自尊、负性情绪的单独中介作用影响其主观幸福感,也可以通过自尊和负性情绪的链式中介作用影响主观幸福感。

由依恋焦虑→自尊→主观幸福感路径可知,自尊是依恋焦虑与主观幸福感间的部分中介变量,依恋焦虑可以通过降低自尊来减少主观幸福感。依恋焦虑反映了个体对被拒绝被抛弃的恐惧[35],自尊反映了个体对自身价值的一般认识[36]。对亲密关系丧失的恐惧可能会降低对自身价值的基本认识,所以依恋焦虑高的个体自尊水平往往偏低[37],而自尊水平低的个体更可能报告更低的生活满意度和主观幸福感[38]。

由依恋焦虑→负性情绪→主观幸福感路径可知,负性情绪也是依恋焦虑与主观幸福感间的部分中介变量,依恋焦虑会诱发负性情绪来降低主观幸福感。研究发现,依恋焦虑与焦虑、抑郁的发生呈正相关[39-40],而焦虑、抑郁情绪会妨碍个体感知幸福感[41]。此路径在总中介效应中占比最高,说明在舰艇官兵依恋焦虑影响主观幸福感的过程中,负性情绪的中介作用大于自尊。

由依恋焦虑→自尊→负性情绪→主观幸福感路径可知,自尊和负性情绪在依恋焦虑与主观幸福感之间发挥着链式中介作用,依恋焦虑可以通过降低自尊来诱发负性情绪,从而降低主观幸福感。依恋焦虑导致了低自尊,低自尊个体容易因为过度寻求安慰、寻求负面反馈、反刍消极自我等而发生焦虑和抑郁[42],从而使其主观幸福感降低。

本研究揭示了自尊和负性情绪在依恋焦虑与主观幸福感关系中的完全链式中介作用,阐明了舰艇官兵依恋焦虑影响主观幸福感的心理机制,为提升舰艇官兵主观幸福感提供了可能的途径和参考依据。根据本研究结果,我们提出以下建议来提升舰艇官兵的主观幸福感:(1)舰艇部队管理部门须有针对性、有特点地开展综合心理卫生活动,普及依恋焦虑、自尊、负性情绪、幸福感等相关心理知识,帮助官兵掌握自身的心理状态。(2)定期开展丰富多彩的专业及娱乐竞赛活动,提升官兵的自我价值感和自我接纳程度。(3)通过正念训练等方式缓解工作压力,降低官兵的焦虑、抑郁情绪,提升主观幸福感。

| [1] |

陈晓丽, 刘大伟, 张淳俊, 等. 某舰艇战士身心健康状况及其影响因素[J]. 解放军预防医学杂志, 2014, 32(6): 508-510. DOI:10.13704/j.cnki.jyyx.2014.06.010 |

| [2] |

郝翠平, 杨富国, 唐凤. ICU护士心理资本、工作压力与工作幸福感的相关性研究[J]. 解放军护理杂志, 2018, 35(21): 20-23, 41. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1008-9993.2018.21.005 |

| [3] |

LESTER P B, STEWART E P, VIE L L, et al. Happy soldiers are highest performers[J]. J Happiness Stud, 2022, 23(3): 1099-1120. DOI:10.1007/s10902-021-00441-x |

| [4] |

DIENER E. Subjective well-being[J]. Psychol Bull, 1984, 95(3): 542-575. DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542 |

| [5] |

ASCONE L, SCHLIER B, SUNDAG J, et al. Pathways from insecure attachment dimensions to paranoia: the mediating role of hyperactivating emotion regulation versus blaming others[J]. Psychol Psychother, 2020, 93(1): 72-87. DOI:10.1111/papt.12208 |

| [6] |

RABY K L, LABELLA M H, MARTIN J, et al. Childhood abuse and neglect and insecure attachment states of mind in adulthood: prospective, longitudinal evidence from a high-risk sample[J]. Dev Psychopathol, 2017, 29(2): 347-363. DOI:10.1017/S0954579417000037 |

| [7] |

DOS SANTOS S B, ROCHA G P, FERNANDEZ L L, et al. Association of lower spiritual well-being, social support, self-esteem, subjective well-being, optimism and hope scores with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia[J]. Front Psychol, 2018, 9: 371. DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00371 |

| [8] |

MALONE C, WACHHOLTZ A. The relationship of anxiety and depression to subjective well-being in a mainland Chinese sample[J]. J Relig Health, 2018, 57(1): 266-278. DOI:10.1007/s10943-017-0447-4 |

| [9] |

BOWLBY J. Attachment and loss: retrospect and prospect[J]. Am J Orthopsychiatry, 1982, 52(4): 664-678. DOI:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x |

| [10] |

ÖZTÜRK A, MUTLU T. The relationship between attachment style, subjective well-being, happiness and social anxiety among university students'[J]. Procedia Soc Behav Sci, 2010, 9: 1772-1776. DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.398 |

| [11] |

BRENNAN K A, CLARK C L, SHAVER P R. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: an integrative overview[M]//SIMPSON J N, RHOLES W S. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford Press, 1998: 46-76.

|

| [12] |

OVERALL N C, FLETCHER G J, SIMPSON J A, et al. Attachment insecurity, biased perceptions of romantic partners' negative emotions, and hostile relationship behavior[J]. J Pers Soc Psychol, 2015, 108(5): 730-749. DOI:10.1037/a0038987 |

| [13] |

WEI M, LIAO K Y H, KU T Y, et al. Attachment, self-compassion, empathy, and subjective well-being among college students and community adults[J]. J Pers, 2011, 79(1): 191-221. DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00677.x |

| [14] |

SERIN N B, SERIN O, ÖZBA L F. Predicting university students' life satisfaction by their anxiety and depression level[J]. Procedia Soc Behav Sci, 2010, 9: 579-582. DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.200 |

| [15] |

ROSENBERG M. Society and the adolescent self-image[M]. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965.

|

| [16] |

CHEN S X, CHEUNG F M, BOND M H, et al. Going beyond self-esteem to predict life satisfaction: the Chinese case[J]. Asian J Social Psycho, 2006, 9(1): 24-35. DOI:10.1111/j.1467-839x.2006.00182.x |

| [17] |

DIENER E. Assessing subjective well-being: progress and opportunities[J]. Soc Indic Res, 1994, 31(2): 103-157. DOI:10.1007/BF01207052 |

| [18] |

PARK L E, CROCKER J, MICKELSON K D, et al. Attachment styles and contingencies of self-worth[J]. Pers Soc Psychol Bull, 2004, 30(10): 1243-1254. DOI:10.1177/0146167204264000 |

| [19] |

何影, 张亚林, 杨海燕, 等. 大学生成人依恋及其与自尊、社会支持的关系[J]. 中国临床心理学杂志, 2010, 18(2): 247-249. DOI:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2010.02.041 |

| [20] |

BOWLBY J. Attachment and loss: attachment[M]. NewYork: BasicBooks, 1982: 27-42.

|

| [21] |

PENG J, ZHANG J, ZHAO L, et al. Coach-athlete attachment and the subjective well-being of athletes: a multiple-mediation model analysis[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020, 17(13): 4675. DOI:10.3390/ijerph17134675 |

| [22] |

TASCA G A, SZADKOWSKI L, ILLING V, et al. Adult attachment, depression, and eating disorder symptoms: the mediating role of affect regulation strategies[J]. Pers Individ Differ, 2009, 47(6): 662-667. DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.006 |

| [23] |

HANKIN B L, KASSEL J D, ABELA J R. Adult attachment dimensions and specificity of emotional distress symptoms: prospective investigations of cognitive risk and interpersonal stress generation as mediating mechanisms[J]. Pers Soc Psychol Bull, 2005, 31(1): 136-151. DOI:10.1177/0146167204271324 |

| [24] |

WEI M, MALLINCKRODT B, LARSON L M, et al. Adult attachment, depressive symptoms, and validation from self versus others[J]. J Couns Psychol, 2005, 52(3): 368-377. DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.368 |

| [25] |

江倩, 许惠静, 高淇, 等. 亚丁湾护航官兵生活满意度与幸福感现状及相关因素分析[J]. 第二军医大学学报, 2021, 42(12): 1413-1418. JIANG Q, XU HJ, GAO Q, et al. Current status and related factors of lifesatisfaction and well-being of soldiers in Chinese navy escort fleets in Aden Gulf[J]. Acad J Sec Mil Med Univ, 2021, 42(12): 1413-1418. DOI:10.16781/j.0258-879x.2021.12.1413 |

| [26] |

LIU Y, WANG Z, ZHOU C, et al. Affect and self-esteem as mediators between trait resilience and psychological adjustment[J]. Pers Individ Differ, 2014, 66: 92-97. DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.023 |

| [27] |

ORTH U, ROBINS R W, MEIER L L. Disentangling the effects of low self-esteem and stressful events on depression: findings from three longitudinal studies[J]. J Pers Soc Psychol, 2009, 97(2): 307-321. DOI:10.1037/a0015645 |

| [28] |

ORTH U, ROBINS R W. The development of self-esteem[J]. Curr Dir Psychol Sci, 2014, 23(5): 381-387. DOI:10.1177/0963721414547414 |

| [29] |

MAO X, LIN X, LIU P, et al. Impact of insomnia on burnout among Chinese nurses under the regular COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control: parallel mediating effects of anxiety and depression[J]. Int J Public Health, 2023, 68: 1605688. DOI:10.3389/ijph.2023.1605688 |

| [30] |

COLLINS N L, READ S J. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples[J]. J Pers Soc Psychol, 1990, 58(4): 644-663. DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644 |

| [31] |

汪向东, 王希林, 马弘. 心理卫生评定量表手册[J]. 中国心理卫生杂志, 1999, 13(1): 31-35. |

| [32] |

SPITZER R L, KROENKE K, WILLIAMS J B, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7[J]. Arch Intern Med, 2006, 166(10): 1092-1097. DOI:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 |

| [33] |

SMARR K L, KEEFER A L. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck depression inventory-Ⅱ (BDI-Ⅱ), Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale (CES-D), geriatric depression scale (GDS), hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), and patient health questionnaire-9(PHQ-9)[J]. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2011, 63(S11): S454-S466. DOI:10.1002/acr.20556 |

| [34] |

刘仁刚, 龚耀先. 纽芬兰纪念大学幸福度量表的试用[J]. 中国临床心理学杂志, 1999, 7(2): 107-108. |

| [35] |

HAZAN C, SHAVER P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process[J]. J Pers Soc Psychol, 1987, 52(3): 511-524. DOI:10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511 |

| [36] |

MÄKIKANGAS A, KINNUNEN U. Psychosocial work stressors and well-being: self-esteem and optimism as moderators in a one-year longitudinal sample[J]. Pers Individ Differ, 2003, 35(3): 537-557. DOI:10.1016/s0191-8869(02)00217-9 |

| [37] |

WU C H. The relationship between attachment style and self-concept clarity: the mediation effect of self-esteem[J]. Pers Individ Differ, 2009, 47(1): 42-46. DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.043 |

| [38] |

ROBINS R W, HENDIN H M, TRZESNIEWSKI K H. Measuring global self-esteem: construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg self-esteem scale[J]. Pers Soc Psychol Bull, 2001, 27(2): 151-161. DOI:10.1177/0146167201272002 |

| [39] |

COLE-DETKE H, KOBAK R. Attachment processes in eating disorder and depression[J]. J Consult Clin Psychol, 1996, 64(2): 282-290. DOI:10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.282 |

| [40] |

COOPER R M, ROWE A C, PENTON-VOAK I S, et al. No reliable effects of emotional facial expression, adult attachment orientation, or anxiety on the allocation of visual attention in the spatial cueing paradigm[J]. J Res Pers, 2009, 43(4): 643-652. DOI:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.03.005 |

| [41] |

STEIN M B, HEIMBERG R G. Well-being and life satisfaction in generalized anxiety disorder: comparison to major depressive disorder in a community sample[J]. J Affect Disord, 2004, 79(1/2/3): 161-166. DOI:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00457-3 |

| [42] |

SOWISLO J F, ORTH U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies[J]. Psychol Bull, 2013, 139(1): 213-240. DOI:10.1037/a0028931 |

2024, Vol. 45

2024, Vol. 45