炎症是人体正常生理防御机制的一种表现,通常由感染、组织损伤或其他异常情况引起。然而,长期或慢性炎症会对心血管系统产生不利影响,可能会增加罹患心脏疾病的风险。例如,CRP是一种广泛用于评估全身炎症的标志物,通常与冠心病风险升高有关;一些炎症生物标志物已被证明可以预测心血管疾病,而不受传统风险因素的影响[1-2]。炎症蛋白在炎症中发挥着关键作用,并与心脏疾病产生复杂的相互作用。以往的研究探讨了某些炎症蛋白在心血管疾病中的功能和潜在影响,如IL-6和IL-1在心血管疾病中起着重要作用,并有望成为某些心血管疾病的治疗靶点[3-4]。尽管这些观察性研究探讨了炎症蛋白在诊断和治疗心血管疾病方面的作用,但其结果可能会受到混杂变量或反向因果关系的影响,从而使因果关系变得更加复杂。因此,一些常见的心脏疾病与大量炎症蛋白之间的因果关系还需要进一步阐明。

孟德尔随机化(Mendelian randomization,MR)分析源于孟德尔遗传定律,通过分析数据中的单核苷酸多态性(single nucleotide polymorphism,SNP)来阐明暴露与结果之间的因果关系[5]。这种分析方法利用了SNP的随机分配特点,将其作为工具变量进行分析[6]。由于等位基因在生殖细胞减数分裂过程中会发生随机分配,MR分析可有效减少混杂因素、测量误差和反向因果关系,从而大大提高研究结果的可靠性[6-7]。本研究利用MR分析和反向MR分析对91种炎症蛋白与5种心血管疾病的因果关系进行分析验证。

1 资料和方法 1.1 研究设计采用MR分析和反向MR分析来研究91种炎症蛋白对5种心血管疾病的双向因果效应。要进行MR分析,需要提出3个重要的假设:相关性假设,即假设工具变量与暴露因素之间存在稳固的相关性;独立性假设,即假设工具变量独立于混杂因素;排他性假设,即假设工具变量只能通过暴露因素对结果产生影响。分析中使用的所有数据都来自公开的和以前发表的数据集,因此无须伦理批准或知情同意。

1.2 数据来源5种心血管疾病的全基因组关联研究(Genome-Wide Association Studies,GWAS)数据来自芬兰基因研究项目(FinnGen),主动脉夹层、动脉瘤、冠心病、非风湿性心瓣膜病和风湿性心瓣膜病的数据编号分别为finngen_R9_I9_AORTDIS、finngen_R9_I9_AORTANEUR、finngen_R9_I9_CHD、finngen_R9_I9_NONRHEVALV、finngen_R9_I9_RHEUVALV。91种炎症蛋白的GWAS数据来自欧洲生物信息研究所GWAS目录数据库(EBI GWAS Catalog Database),其数据集来自对91种血浆蛋白质的全基因组蛋白质定量性状位点(protein quantitative trait loci,pQTL)分析[8]。该项研究利用了Olink精准蛋白质组学技术(Olink Target 96 Inflammation Panels),可以对样本进行系统免疫图谱扫描,检测其中包含的92种炎症相关蛋白标志物,但由于检测问题,该研究团队移除了脑源性神经营养性因子(brain-derived neurotrophic factor,BDNF),故而包含91种炎症蛋白。该项研究综合了11个队列,总计14 824名欧洲居民参与者。

1.3 工具变量选择为确保符合MR分析的关联假说,利用P<5×10-8或P<5×10-6的阈值[9],选择与暴露有强相关性的SNP。对于每种疾病,采用P<5×10-6的阈值鉴定出3个及以上的SNP,但对于冠心病,采用了P<5×10-8这一更为严格的阈值。为了降低连锁不平衡的风险,对这些SNP采用了聚类分析(距离设置为10 000 kb,r2设置为0.001)。在GWAS中,等位SNP在暴露和结果方面的排列不确定,因此这些SNP被排除。同时,利用每个SNP的r2值确定暴露变异的比例。工具强度通过F值来衡量,F=r2(N-2)/(1-r2),其中N表示样本量。F值低于10的SNP被排除在外,以减少弱工具带来的偏差[10-11]。丢失的SNP使用从LDlink(https://ldlink.nci.nih.gov/)获得的r2>0.9的SNP进行替代[12]。

1.4 MR方法采用多种MR分析方法评估91种炎症蛋白与5种心血管疾病之间的因果关系。通过反向MR分析研究潜在的反向因果关系。主要分析采用逆方差加权(inverse variance weighted,Ⅳ)方法,该方法综合了各种SNP因果效应的Wald比值估计值,对暴露与结果的因果关系进行评估[13]。然而,该方法预设了所有工具变量的有效性,在实际应用中并不总是成立,因此补充了其他允许工具变量存在误差的方法以提高结果的可靠性。加权中位数(weighted median)对无效工具变量的容忍度更高,当有效工具变量权重超过50%时,即可提供可靠的估计值[14]。MR-Egger回归方法侧重于评估无效因果假设并确保因果关系评估的一致性,包括工具变量表现出遗传变异不足的情况[15]。加权模式(weighted mode)通过关注众数的效应值,能够有效地捕捉最具代表性的因果关系,尤其是在涉及多个工具变量的情况下。简单模式(simple mode)也是基于众数效应进行分析的一种方法,它对极端值具有更强的适应能力,不受少量极端数据的影响;同时,在工具变量效应大小分布不均或存在显著异质性的情况下,简单模式可以有效地提供中心倾向的估计值。当Ⅳ方法得出P<0.05且所有MR分析方法的β值方向相同时,判定为阳性结果。此外,当MR-Egger截距检验和MR-PRESSO方法均得出P>0.05时,判定为不存在水平多效性。

1.5 敏感性分析采用Cochran’s Q检验、MR-Egger截距检验、MR-PRESSO方法和留一法(leave-one-out)进行敏感性分析,以提高研究结果的可靠性和稳健性。Cochran’s Q检验用于检测潜在的异质性,旨在评估工具变量的变化是否会导致不同的结果[16]。MR-PRESSO方法专门用于识别表现出水平多效性的离群SNP,前提是超过50%的工具变量有效[17]。MR-Egger截距检验用于检测潜在的垂直多效性,其特点是工具变量通过独立于暴露的途径影响结果[15]。留一法逐一地剔除每个SNP后重新评估剩余SNP的效应值,旨在通过评估每个SNP对总体结果的影响来验证结果的可靠性和稳健性。

1.6 统计学处理使用R 4.1.2软件TwoSampleMR包和MR-PRESSO包进行数据分析。

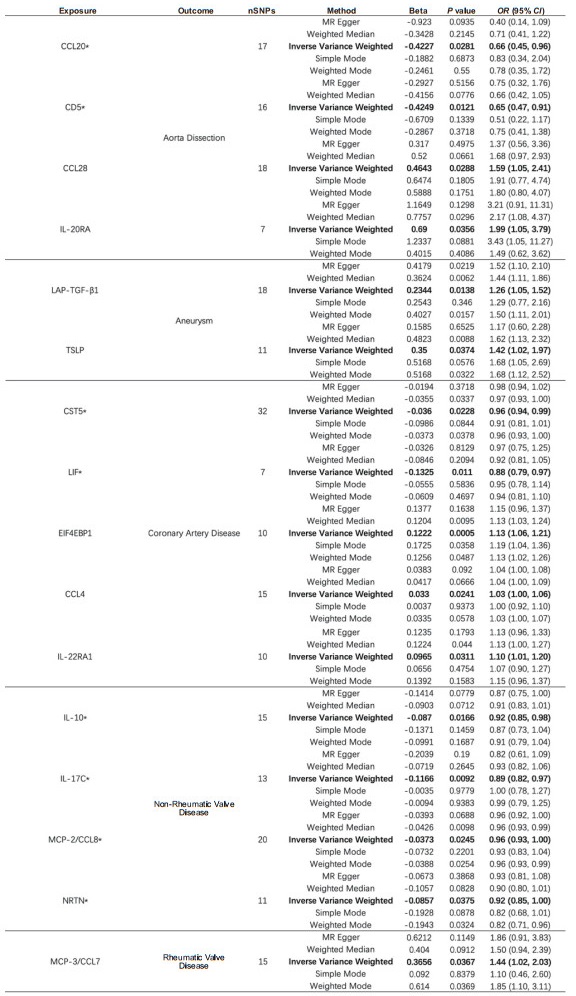

2 结果 2.1 91种炎症蛋白对5种心血管疾病的影响如图 1所示,在主动脉夹层中,C-C趋化因子配体(C-C motif chemokine ligand,CCL)20和CD5为保护因素,CCL28和白细胞介素20受体α(interleukin 20 receptor α,IL-20RA)为危险因素;在动脉瘤中,潜在转化生长因子β1前体(latency-associated peptide transforming growth factor β1,LAP-TGF-β1)和胸腺基质淋巴细胞生成素(thymic stromal lymphopoietin,TSLP)为危险因素;在冠心病中,胱抑素D(cystatin D,CST5)和白血病抑制因子(leukemia inhibitory factor,LIF)是保护因素,翻译起始因子4E结合蛋白1(eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1,EIF4EBP1)、CCL4和白细胞介素22受体α1(interleukin 22 receptor α1,IL-22RA1)是危险因素;在非风湿性心瓣膜病中,IL-10、IL-17C、单核细胞趋化蛋白(monocyte chemoattractant protein,MCP)-2/CCL8和神经秩蛋白(neurturin,NRTN)是保护因素;在风湿性心瓣膜病中,MCP-3/CCL7是危险因素。

|

图 1 91种炎症蛋白与5种心血管疾病之间MR分析中的阳性结果 Fig 1 Positive results in MR analysis between 91 inflammatory proteins and 5 cardiovascular diseases *: Exposure was negatively associated with outcome. OR and 95% CI indicate change in outcome OR per 1 standard deviation increase in exposure. MR: Mendelian randomization; CCL: C-C motif chemokine ligand; IL-20RA: Interleukin 20 receptor α; LAP-TGF-β1: Latency-associated peptide transforming growth factor β1; TSLP: Thymic stromal lymphopoietin; CST5: Cystatin D; LIF: Leukemia inhibitory factor; EIF4EBP1: Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1; IL-22RA1: Interleukin 22 receptor α1; IL-10: Interleukin 10; IL-17C: Interleukin 17C; MCP: Monocyte chemoattractant protein; NRTN: Neurturin; nSNPs: Number of single nucleotide polymorphisms; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval. |

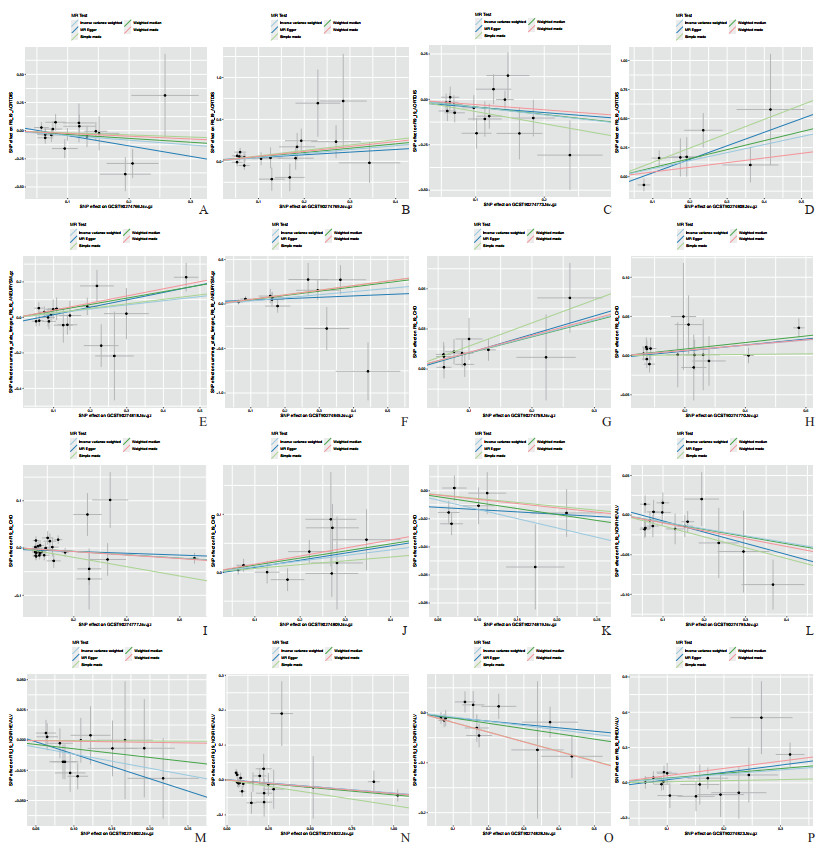

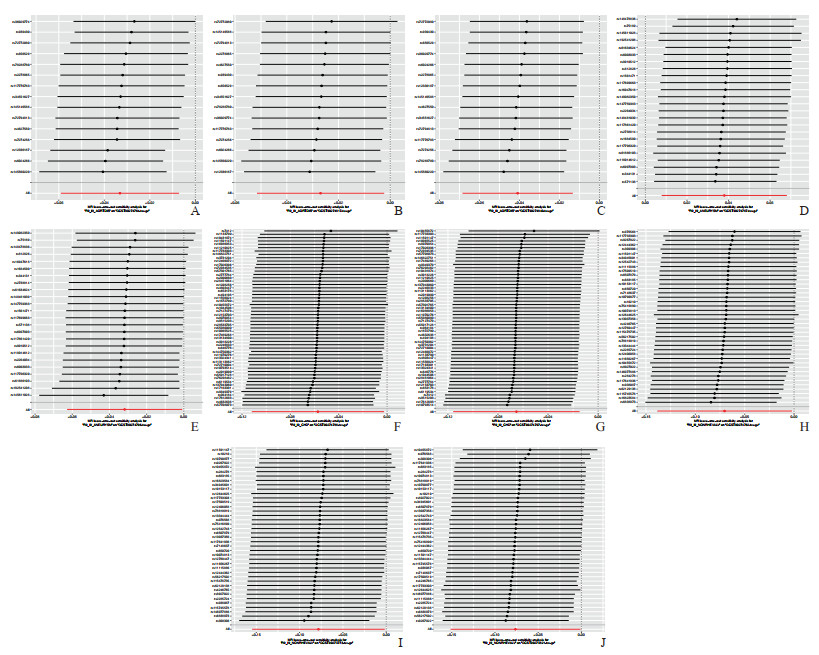

Cochran’s Q检验结果显示,暴露与结果之间的关系存在相当大的异质性。实施随机效应Ⅳ分析可一定程度减轻结果中的异质性。此外,MR-Egger截距检验和MR-PRESSO均未发现偏差,这表明MR分析的可靠性及其在异质性中抵御潜在多向性偏差的能力。留一法表明研究结果并非由单个SNP驱动。散点图和剔除敏感性分析见图 2和图 3。

|

图 2 91种炎症蛋白与5种心血管疾病之间MR分析的散点图 Fig 2 Scatter plot of MR analysis between 91 inflammatory proteins and 5 cardiovascular diseases The single inverse variance (Ⅳ) related to exposure risk and the single Ⅳ related to outcomes (indicated by black dots) correspond to each other. The 95% confidence intervals of the odds ratios for each Ⅳ are represented by vertical and horizontal lines. The slope of these lines indicates the estimated causal effect analyzed by the MR method. A-D: The relationships between aortic dissection (outcome) and inflammatory proteins CCL20, CCL28, CD5, and IL-20RA, respectively; E, F: The relationships between aneurysm (outcome) and inflammatory proteins LAP-TGF-β1 and TSLP, respectively; G-K: The relationships between coronary artery disease (outcome) and inflammatory proteins EIF4EBP1, CCL4, CST5, IL-22RA1, and LIF, respectively; L-O: The relationships between non-rheumatic valve disease (outcome) and inflammatory proteins IL-10, IL-17C, MCP-2/CCL8, and NRTN, respectively; P: The relationship between rheumatic valve disease (outcome) and inflammatory protein MCP-3/CCL7. MR: Mendelian randomization; CCL: C-C motif chemokine ligand; IL-20RA: Interleukin 20 receptor α; LAP-TGF-β1: Latency-associated peptide transforming growth factor β1; TSLP: Thymic stromal lymphopoietin; EIF4EBP1: Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1; CST5: Cystatin D; IL-22RA1: Interleukin 22 receptor α1; LIF: Leukemia inhibitory factor; IL-10: Interleukin 10; IL-17C: Interleukin 17C; MCP: Monocyte chemoattractant protein; NRTN: Neurturin; SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism. |

|

图 3 对91种炎症蛋白和5种心血管疾病进行MR分析的留一图 Fig 3 Leave-one-out analysis for MR studies on 91 inflammatory proteins and 5 cardiovascular diseases A-D: The relationships between aortic dissection (outcome) and inflammatory proteins CCL20, CCL28, CD5, and IL-20RA, respectively; E, F: The relationships between aneurysm (outcome) and inflammatory proteins LAP-TGF-β1 and TSLP, respectively; G-K: The relationships between coronary artery disease (outcome) and inflammatory proteins EIF4EBP1, CCL4, CST5, IL-22RA1, and LIF, respectively; L-O: The relationships between non-rheumatic valve disease (outcome) and inflammatory proteins IL-10, IL-17C, MCP-2/CCL8, and NRTN, respectively; P: The relationship between rheumatic valve disease (outcome) and inflammatory protein MCP-3/CCL7. MR: Mendelian randomization; CCL: C-C motif chemokine ligand; IL-20RA: Interleukin 20 receptor α; LAP-TGF-β1: Latency-associated peptide transforming growth factor β1; TSLP: Thymic stromal lymphopoietin; EIF4EBP1: Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1; CST5: Cystatin D; IL-22RA1: Interleukin 22 receptor α1; LIF: Leukemia inhibitory factor; IL-10: Interleukin 10; IL-17C: Interleukin 17C; MCP: Monocyte chemoattractant protein; NRTN: Neurturin. |

2.2 5种心血管疾病对91种炎症蛋白的影响

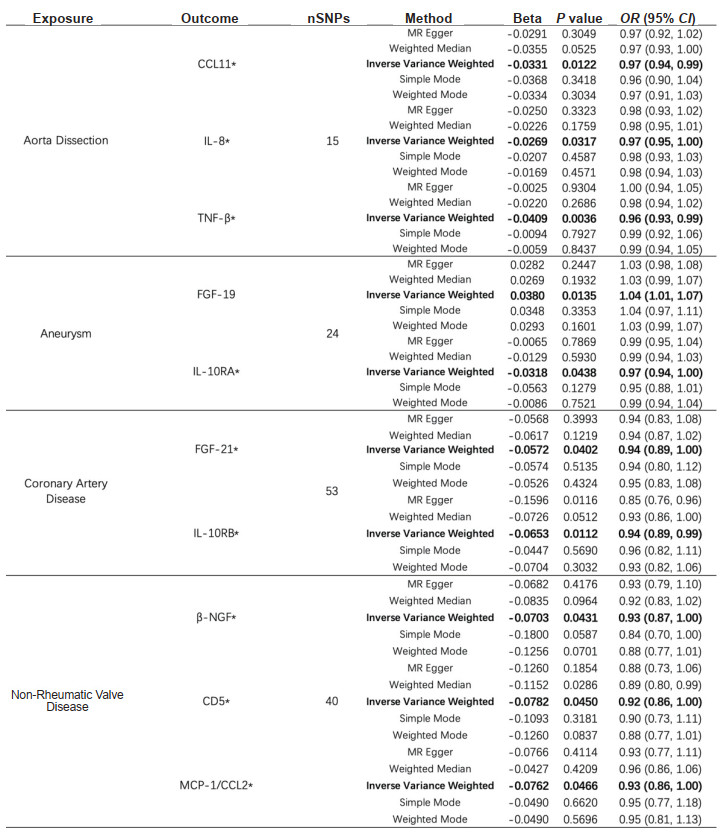

如图 4所示,主动脉夹层与CCL11、IL-8和TNF-β呈负相关;动脉瘤与成纤维细胞生长因子(fibroblast growth factor,FGF)-19呈正相关,而与白细胞介素10受体α(interleukin 10 receptor α,IL-10RA)呈负相关;冠心病与FGF-21和白细胞介素10受体β(interleukin 10 receptor β,IL-10RB)呈负相关;非风湿性心瓣膜病与β-神经生长因子(β-nerve growth factor,β-NGF)、CD5和MCP-1/CCL2呈负相关;风湿性心瓣膜病与所研究的91种炎症蛋白没有明显的反向MR因果关系。

|

图 4 91种炎症蛋白与5种心血管疾病之间反向MR分析中的阳性结果 Fig 4 Positive results in reverse MR analysis between 91 inflammatory proteins and 5 cardiovascular diseases *: Exposure was negatively associated with outcome. OR and 95% CI indicate change in outcome OR per 1 standard deviation increase in exposure. MR: Mendelian randomization; CCL: C-C motif chemokine ligand; IL-8: Interleukin 8; TNF-β: Tumor necrosis factor β; FGF: Fibroblast growth factor; IL-10RA: Interleukin 10 receptor α; IL-10RB: Interleukin 10 receptor β; β-NGF: β-nerve growth factor; MCP: Monocyte chemoattractant protein; nSNPs: Number of single nucleotide polymorphisms; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval. |

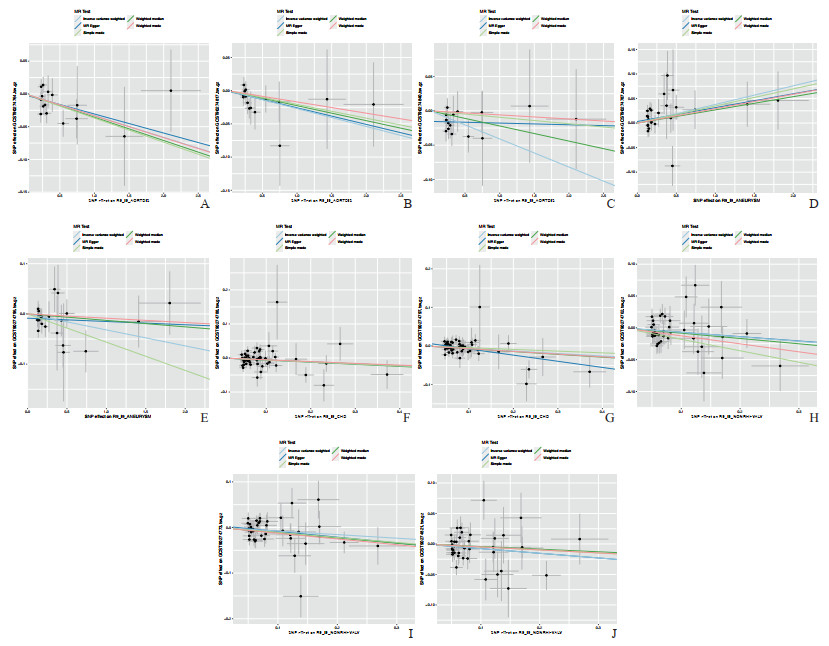

Cochran’s Q检验表明,暴露与结果之间存在异质性,但随机效应Ⅳ方法证实了反向MR分析的可靠性。这种可靠性归因于随机效应Ⅳ方法能够减轻结果中的异质性。此外,MR-Egger截距测试和MR-PRESSO方法进一步验证了MR分析结果的可靠性。留一法表明研究结果并不依赖于任何单个SNP。散点图和剔除敏感性分析见图 5和图 6。

|

图 5 5种心血管疾病与91种炎症蛋白之间反向MR分析的散点图 Fig 5 Scatter plot of inverse MR analysis between 5 cardiovascular diseases and 91 inflammatory proteins The single inverse variance (Ⅳ) related to exposure risk and the single Ⅳ related to outcomes (indicated by black dots) correspond to each other. The 95% confidence intervals of the odds ratios for each Ⅳ are represented by vertical and horizontal lines. A-C: The relationships between aortic dissection (exposure) and inflammatory proteins CCL11, IL-8, and TNF-β, respectively; D, E: The relationships between aneurysm (exposure) and inflammatory proteins FGF-19 and IL-10RA, respectively; F, G: The relationships between coronary artery disease (exposure) and inflammatory proteins FGF-21 and IL-10RB, respectively; H-J: The relationships between non-rheumatic valve disease (exposure) and inflammatory proteins β-NGF, CD5, and MCP-1/CCL2, respectively. CCL: C-C motif chemokine ligand; IL-8: Interleukin 8; TNF-β: Tumor necrosis factor β; FGF: Fibroblast growth factor; IL-10RA: Interleukin 10 receptor α; IL-10RB: Interleukin 10 receptor β; β-NGF: β-nerve growth factor; MCP: Monocyte chemoattractant protein; SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism. |

|

图 6 5种心血管疾病与91种炎症蛋白之间反向MR分析的留一图 Fig 6 Leave-one-out plot of inverse MR analysis between 5 cardiovascular diseases and 91 inflammatory proteins A-C: The relationships between aortic dissection (exposure) and inflammatory proteins CCL11, IL-8, and TNF-β, respectively; D, E: The relationships between aneurysm (exposure) and inflammatory proteins FGF-19 and IL-10RA, respectively; F, G: The relationships between coronary artery disease (exposure) and inflammatory proteins FGF-21 and IL-10RB, respectively; H-J: The relationships between non-rheumatic valve disease (exposure) and inflammatory proteins β-NGF, CD5, and MCP-1/CCL2, respectively. CCL: C-C motif chemokine ligand; IL-8: Interleukin 8; TNF-β: Tumor necrosis factor β; FGF: Fibroblast growth factor; IL-10RA: Interleukin 10 receptor α; IL-10RB: Interleukin 10 receptor β; β-NGF: β-nerve growth factor; MCP: Monocyte chemoattractant protein. |

3 讨论

本研究采用MR方法对91种炎症蛋白与5种心血管疾病之间的潜在因果关系进行了初步分析,随后用反向MR方法评估了反向因果关系的可能性。研究结果表明,CCL20和CD5可能是主动脉夹层的上游保护因素,而CCL28和IL-20RA可能是主动脉夹层的上游危险因素;此外,主动脉夹层的发生可能导致CCL11、IL-8和TNF-β水平下降。在动脉瘤中,LAP-TGF-β1和TSLP可被视为上游危险因素,而疾病进展可能导致IL-10RA水平下降和FGF-19水平上升。对于冠心病,上游保护因素包括CST5和LIF,而上游危险因素包括EIF4EBP1、CCL4和IL-22RA1;其发病可能会导致FGF-21和IL-10RB水平降低。在非风湿性心瓣膜病中,上游保护因素包括IL-10、IL-17C、MCP-2/CCL8和NRTN,而疾病进展可能会导致下游的β-NGF、CD5和MCP-1/CCL2水平降低。在风湿性心瓣膜病中,上游危险因素是MCP-3/CCL7,没有发现明显的下游变化。

值得注意的是,本研究发现CD5水平与非风湿性心瓣膜病和主动脉夹层有显著相关性。基于这一结果,我们提出了一个假设,即非风湿性心瓣膜病的进展可能会导致下游CD5水平的降低,鉴于CD5被认为是防止主动脉夹层的上游保护因子,CD5水平的降低可能会增加罹患这种疾病的风险。有趣的是,多项研究表明主动脉瓣双瓣疾病有时与主动脉逐渐扩张有关,有可能导致主动脉夹层风险增加[18-19]。虽然这种现象可能与局部血流动力学变化有关,但某些研究提出了潜在的细胞原因[20-21]。CD5是慢性淋巴性白血病中T细胞、B1-a细胞和B细胞的生物标志物,在调节T细胞和B细胞活化、促进免疫耐受和减轻过度炎症反应方面起着关键作用[22-23]。非风湿性心瓣膜病经常与慢性炎症和心瓣膜结构改变有关,这些过程涉及免疫系统的激活和调节[24]。这一疾病过程可能会破坏免疫调节的平衡,影响免疫细胞的活性和细胞因子的释放,从而对CD5水平产生负面影响。因此,这种破坏可能会引发多米诺骨牌效应,导致严重的免疫反应、炎症和动脉壁损伤,从而损害动脉壁的完整性并增加主动脉夹层的风险。然而,这些推断都是初步的,需要进一步的实验验证,其具体的机制仍未完全阐明。

迄今为止,已有大量研究探讨了炎症蛋白与心血管疾病之间的相关性。随机对照试验结果显示,对于服用他汀类药物的患者来说,高敏CRP比低密度脂蛋白胆固醇水平更能预测未来的心血管事件和死亡率[25]。IL-6、IL-18、基质金属蛋白酶9、可溶性CD40配体和TNF-α等促炎细胞因子都与冠心病风险的增加独立相关[26]。此外,与安慰剂相比,以IL-1β免疫性为重点的抗炎疗法可显著降低心血管事件的复发率[4, 27-28]。

之前的研究主要集中于研究炎症与心血管疾病之间的关系,通常是将特定的炎症因素与单一疾病联系起来。已有研究者通过MR方法探讨了各类暴露(如肠道菌群[29-30]、血清代谢物[31])与特定疾病之间的因果关系,但炎症与心血管疾病之间的MR分析尚未见报道。本研究通过MR和反向MR方法初步探讨了91种炎症蛋白与5种心血管疾病之间的双向因果关系,探索了这几种疾病的潜在上游影响和下游后果。

本研究还存在一些不足:(1)本研究使用的GWAS数据集主要来自欧洲居民,缺乏其他种族群体的数据,这可能会导致估计结果有偏差,并影响本研究结果的普适性。(2)本研究收集的数据为横断面数据,考虑到疾病发病率的时间依赖性,缺乏暴露测量的纵向数据可能会给分析结果带来部分偏差。(3)本研究无法全面评估独立性和排他性假说,这有可能导致偏差。未来的研究应采用综合的方法,整合多组学技术[32-33],以便在复杂的基因-环境相互作用中更深入地了解疾病的发病机制。

| [1] |

RIDKER P M. A test in context: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2016, 67(6): 712-723. DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.11.037 |

| [2] |

RIDKER P M, KOENIG W, KASTELEIN J J, et al. Has the time finally come to measure hsCRP universally in primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention?[J]. Eur Heart J, 2018, 39(46): 4109-4111. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy723 |

| [3] |

RIDKER P M, RANE M. Interleukin-6 signaling and anti-interleukin-6 therapeutics in cardiovascular disease[J]. Circ Res, 2021, 128(11): 1728-1746. DOI:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319077 |

| [4] |

ABBATE A, TOLDO S, MARCHETTI C, et al. Interleukin-1 and the inflammasome as therapeutic targets in cardiovascular disease[J]. Circ Res, 2020, 126(9): 1260-1280. DOI:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.315937 |

| [5] |

BURGESS S, DAVEY SMITH G, DAVIES N M, et al. Guidelines for performing Mendelian randomization investigations: update for summer 2023[J]. Wellcome Open Res, 2023, 4: 186. DOI:10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15555.3 |

| [6] |

BURGESS S, SCOTT R A, TIMPSON N J, et al. Using published data in Mendelian randomization: a blueprint for efficient identification of causal risk factors[J]. Eur J Epidemiol, 2015, 30(7): 543-552. DOI:10.1007/s10654-015-0011-z |

| [7] |

DAVEY SMITH G, HEMANI G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2014, 23(R1): R89-R98. DOI:10.1093/hmg/ddu328 |

| [8] |

ZHAO J H, STACEY D, ERIKSSON N, et al. Genetics of circulating inflammatory proteins identifies drivers of immune-mediated disease risk and therapeutic targets[J]. Nat Immunol, 2023, 24(9): 1540-1551. DOI:10.1038/s41590-023-01588-w |

| [9] |

MENG Y, TAN Z, SU Y, et al. Causal association between common rheumatic diseases and glaucoma: a Mendelian randomization study[J]. Front Immunol, 2023, 14: 1227138. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1227138 |

| [10] |

PALMER T M, LAWLOR D A, HARBORD R M, et al. Using multiple genetic variants as instrumental variables for modifiable risk factors[J]. Stat Methods Med Res, 2012, 21(3): 223-242. DOI:10.1177/0962280210394459 |

| [11] |

PIERCE B L, AHSAN H, VANDERWEELE T J. Power and instrument strength requirements for Mendelian randomization studies using multiple genetic variants[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2011, 40(3): 740-752. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyq151 |

| [12] |

MACHIELA M J, CHANOCK S J. LDlink: a web-based application for exploring population-specific haplotype structure and linking correlated alleles of possible functional variants[J]. Bioinformatics, 2015, 31(21): 3555-3557. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv402 |

| [13] |

PIERCE B L, BURGESS S. Efficient design for Mendelian randomization studies: subsample and 2-sample instrumental variable estimators[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2013, 178(7): 1177-1184. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwt084 |

| [14] |

BOWDEN J, DAVEY SMITH G, HAYCOCK P C, et al. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator[J]. Genet Epidemiol, 2016, 40(4): 304-314. DOI:10.1002/gepi.21965 |

| [15] |

BOWDEN J, DAVEY SMITH G, BURGESS S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2015, 44(2): 512-525. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyv080 |

| [16] |

COHEN J F, CHALUMEAU M, COHEN R, et al. Cochran's Q test was useful to assess heterogeneity in likelihood ratios in studies of diagnostic accuracy[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2015, 68(3): 299-306. DOI:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.09.005 |

| [17] |

VERBANCK M, CHEN C Y, NEALE B, et al. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases[J]. Nat Genet, 2018, 50(5): 693-698. DOI:10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7 |

| [18] |

DUNNE E C, LACRO R V, FLYER J N. Bicuspid aortic valve and its ascending aortopathy[J]. Curr Opin Pediatr, 2023, 35(5): 538-545. DOI:10.1097/MOP.0000000000001276 |

| [19] |

SIU S C, SILVERSIDES C K. Bicuspid aortic valve disease[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2010, 55(25): 2789-2800. DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.068 |

| [20] |

FEDAK P W M, DE SA M P L, VERMA S, et al. Vascular matrix remodeling in patients with bicuspid aortic valve malformations: implications for aortic dilatation[J]. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2003, 126(3): 797-806. DOI:10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00398-2 |

| [21] |

BOYUM J, FELLINGER E K, SCHMOKER J D, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase activity in thoracic aortic aneurysms associated with bicuspid and tricuspid aortic valves[J]. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2004, 127(3): 686-691. DOI:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.11.049 |

| [22] |

DALLOUL A. CD5: a safeguard against autoimmunity and a shield for cancer cells[J]. Autoimmun Rev, 2009, 8(4): 349-353. DOI:10.1016/j.autrev.2008.11.007 |

| [23] |

RAMAN C. CD5, an important regulator of lymphocyte selection and immune tolerance[J]. Immunol Res, 2002, 26(1/2/3): 255-263. DOI:10.1385/IR:26:1-3:255 |

| [24] |

MARTIN M, MOTTA S E, EMMERT M Y. Have we found the missing link between inflammation, fibrosis, and calcification in calcific aortic valve disease?[J]. Eur Heart J, 2023, 44(10): 899-901. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac787 |

| [25] |

RIDKER P M, BHATT D L, PRADHAN A D, et al. Inflammation and cholesterol as predictors of cardiovascular events among patients receiving statin therapy: a collaborative analysis of three randomised trials[J]. Lancet, 2023, 401(10384): 1293-1301. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00215-5 |

| [26] |

KAPTOGE S, SESHASAI S R K, GAO P, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and risk of coronary heart disease: new prospective study and updated meta-analysis[J]. Eur Heart J, 2014, 35(9): 578-589. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/eht367 |

| [27] |

RIDKER P M, EVERETT B M, THUREN T, et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 377(12): 1119-1131. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1707914 |

| [28] |

BUCKLEY L F, ABBATE A. Interleukin-1 blockade in cardiovascular diseases: from bench to bedside[J]. BioDrugs, 2018, 32(2): 111-118. DOI:10.1007/s40259-018-0274-5 |

| [29] |

KURILSHIKOV A, MEDINA-GOMEZ C, BACIGALUPE R, et al. Large-scale association analyses identify host factors influencing human gut microbiome composition[J]. Nat Genet, 2021, 53(2): 156-165. DOI:10.1038/s41588-020-00763-1 |

| [30] |

SUN K, GAO Y, WU H, et al. The causal relationship between gut microbiota and type 2 diabetes: a two-sample Mendelian randomized study[J]. Front Public Health, 2023, 11: 1255059. DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1255059 |

| [31] |

LIU X, TONG X, ZOU Y, et al. Mendelian randomization analyses support causal relationships between blood metabolites and the gut microbiome[J]. Nat Genet, 2022, 54(1): 52-61. DOI:10.1038/s41588-021-00968-y |

| [32] |

YAZAR S, ALQUICIRA-HERNANDEZ J, WING K, et al. Single-cell eQTL mapping identifies cell type-specific genetic control of autoimmune disease[J]. Science, 2022, 376(6589): eabf3041. DOI:10.1126/science.abf3041 |

| [33] |

ZHANG J, CHEN Z, PÄRNA K, et al. Mediators of the association between educational attainment and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a two-step multivariable Mendelian randomisation study[J]. Diabetologia, 2022, 65(8): 1364-1374. DOI:10.1007/s00125-022-05705-6 |

2024, Vol. 45

2024, Vol. 45