认知障碍是一类以获得性认知功能损害为核心,可导致患者日常生活、社会交往和工作能力等明显减退的综合征,包括轻度认知障碍和痴呆[1]。随着社会老龄化的发展,认知障碍的发病率逐年升高,已成为影响患者生活质量的严重公共卫生问题[2]。研究表明,女性认知障碍的发生率高于男性,尤其绝经后女性认知障碍的患病风险明显增加,约为同年龄段男性的2倍[3-4]。因此,关注绝经后女性认知功能减退,探究绝经后女性认知障碍的病因,对于该病的早期诊断和干预具有重要意义。

绝经是女性必经的自然生理过程,其显著特点是卵巢功能衰退、雌激素水平下降及月经停止。随着月经停止、自主铁丢失减少,体内铁水平较绝经前明显升高[5-6]。铁死亡是一种铁依赖性的脂质过氧化物(lipid hydroperoxide,LPO)积累引起的细胞死亡方式[7],体内铁增加引起的铁死亡可能是影响绝经后女性认知功能的重要因素。基础研究证明,脑铁沉积、铁死亡在认知障碍的发生与发展中起着重要作用[8-10],但目前尚无有关外周血清铁死亡相关指标与绝经后女性认知障碍关系的报道。铁死亡过程涉及铁代谢、谷胱甘肽代谢和脂质过氧化反应等多个方面[11],本研究以绝经后女性为研究对象,探讨血清铁死亡相关指标与绝经后女性认知障碍的关系。

1 资料和方法 1.1 研究对象选择2019年8月至2021年12月就诊于海军军医大学(第二军医大学)第一附属医院神经内科的女性患者148例。纳入标准:(1)年龄≥18岁;(2)小学及以上文化程度且能够配合完成神经心理学量表评估。排除标准:(1)神经梅毒、药物滥用或酗酒等明确病因导致的认知障碍;(2)存在严重的视觉、听觉损伤;(3)有严重焦虑、抑郁等精神问题。通过面对面访谈或电话沟通,根据月经规律,有无经期延迟并出现潮热、易怒等围绝经期综合征,以及停经是否1年以上将患者分为3组:生育期组(22例)、围绝经期组(11例)和绝经后组(115例)。本研究经海军军医大学(第二军医大学)第一附属医院伦理委员会审批(B2021-047)。

1.2 研究方法 1.2.1 一般资料收集收集患者的基本情况,包括年龄、受教育年限、高血压病史、糖尿病史、高脂血症病史、吸烟史、饮酒史和卒中病史等。

1.2.2 认知功能评估采用蒙特利尔认知评估量表(Montreal cognitive assessment,MoCA)对患者进行认知功能评估[12]。MoCA的重测信度高(重测信度为0.92),内部一致性较好(Cronbach’s α系数为0.83),与简易精神状态检查量表显著相关(相关系数为0.87)[12]。

由获得国家认知测量师资质的临床医师在经过量表标准化评分培训后进行评估。根据MoCA评分规则,女性受教育年限≤12年加1分。MoCA评分最高分为30分,MoCA评分越低提示认知功能受损越严重。MoCA评分≥26分表示认知功能正常,MoCA评分<26分提示认知障碍[12]。

1.2.3 血液标本采集及检测采集患者晨起空腹静脉血送检,用ELISA检测试剂盒(上海博光生物科技有限公司)检测血清铁水平。另采集4 mL静脉血取血清,用ELISA检测试剂盒(上海博光生物科技有限公司)检测血清中铁死亡相关指标(谷胱甘肽代谢指标、脂质过氧化反应指标)。谷胱甘肽代谢指标包括谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶4(glutathione peroxidase 4,GPX4)、还原型谷胱甘肽(reduced glutathione,GSH)和胱氨酸/谷氨酸反向转运体(cystine/glutamate antiporter,Xc-系统),脂质过氧化反应指标包括酰基辅酶A合成酶长链家族成员4(acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4,ACSL4)、活性氧(reactive oxygen species,ROS)、LPO和丙二醛(malondialdehyde,MDA)[11]。

1.3 统计学处理应用SPSS 26.0软件进行数据分析。计数资料以例数和百分数表示,组间比较采用χ2检验,多重比较采用Bonferroni法。对计量资料进行Shapiro-Wilk检验,呈正态分布的计量资料以x±s表示,两组间比较采用独立样本t检验,多组间比较采用单因素方差分析,多重比较采用Bonferroni法;呈偏态分布的计量资料以中位数(下四分位数,上四分位数)表示,两组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验,多组间采用Kruskal-Wallis H检验,多重比较采用Bonferroni法。采用多重logistic回归模型,通过条件参数估计似然比检验(向前:条件)筛选变量,分析绝经后女性认知障碍的影响因素,并采用ROC曲线评估其对绝经后女性认知障碍的诊断价值。检验水准(α)为0.05。

2 结果 2.1 3组女性的一般资料及血清铁死亡相关指标比较共入组148例女性,其中生育期22例,年龄20~44岁,平均(31.36±8.73)岁;围绝经期11例,年龄45~52岁,平均(49.55±2.30)岁;绝经后115例,年龄56~79岁,平均(67.06±5.58)岁。绝经后女性受教育年限短于生育期女性(P<0.01),绝经后与围绝经期女性受教育年限差异无统计学意义(P=0.266)。绝经后女性的MoCA评分低于生育期女性(P<0.01)和围绝经期女性(P=0.037)。绝经后女性患高血压病和糖尿病的比例高于生育期和围绝经期女性(均P<0.05);绝经后女性和围绝经期女性患高脂血症及有卒中病史的比例均高于生育期女性(均P<0.05)。3组女性吸烟史和饮酒史差异无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。见表 1。

|

|

表 1 3组女性的一般资料和血清铁死亡相关指标比较 Tab 1 Comparison of general information and serum ferroptosis-related indexes among women in 3 groups |

生育期女性未常规行血清铁检测。绝经后和围绝经期女性的血清铁水平差异无统计学意义(P=0.290)。绝经后女性血清谷胱甘肽代谢指标Xc-系统高于生育期女性(P<0.01),GPX4水平高于围绝经期和生育期女性(均P<0.05);围绝经期和绝经后女性GSH水平均高于生育期女性(均P<0.05)。绝经后女性血清脂质过氧化反应指标ACSL4水平高于生育期女性(P<0.01),ROS和MDA水平均高于围绝经期和生育期女性(均P<0.01);围绝经期和绝经后女性LPO水平均高于生育期女性(均P<0.05)。见表 1。

2.2 认知障碍与无认知障碍绝经后女性的一般资料及铁死亡相关指标比较无认知障碍组绝经后女性38例,认知障碍组绝经后女性77例。两组绝经后女性年龄差异无统计学意义(P=0.097)。认知障碍组绝经后女性受教育年限短于无认知障碍组(P=0.001),患高血压病的比例高于无认知障碍组(P<0.001),有吸烟史的比例低于无认知障碍组(P=0.002)。两组血清铁水平差异无统计学意义(P=0.102)。认知障碍组血清Xc-系统、GPX4、GSH、ACSL4、ROS、LPO和MDA水平均高于无认知障碍组(均P<0.05)。见表 2。

|

|

表 2 认知障碍组和无认知障碍组绝经后女性的一般资料和血清铁死亡相关指标比较 Tab 2 Comparison of general information and serum ferroptosis-related indexes of postmenopausal women with and without cognitive impairment |

2.3 绝经后女性认知障碍的影响因素分析

将表 2中差异有统计学意义的变量及年龄纳入多重logistic回归模型,结果显示受教育年限与绝经后女性认知障碍风险呈负相关(OR=0.785,95% CI 0.662~0.930,P=0.005),而血清GSH水平(OR=1.291,95% CI 1.087~1.534,P=0.004)与绝经后女性认知障碍的发生呈正相关。

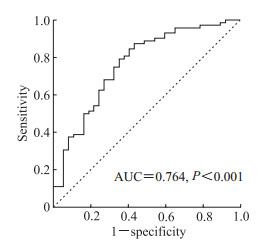

2.4 教育年限联合GSH对绝经后女性认知障碍的诊断价值ROC曲线分析结果显示,受教育年限和GSH联合诊断绝经后女性认知障碍的AUC值为0.764(P<0.001),灵敏度为0.750,特异度为0.676。见图 1。

|

图 1 受教育年限联合血清GSH诊断绝经后女性认知障碍的ROC曲线分析 Fig 1 ROC curve analysis of education level combined with serum GSH in diagnosis of cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women GSH: Reduced glutathione; ROC: Receiver operating characteristic; AUC: Area under curve. |

3 讨论

绝经后女性会出现多种不适,44%~72%的绝经后女性有主观认知障碍[13-15]。本研究中绝经后女性认知障碍的发生率为67.0%(77/115),与既往报道[13-15]一致。国内横断面调查显示,绝经后女性认知障碍的患病率约为20%[16-17],明显低于本研究结果,考虑原因可能是本研究的患者均来自神经内科门诊和病房,而门诊和病房较流行病学调查有富集效应。女性雌激素水平在绝经前后变化显著,一直是绝经后女性认知障碍研究的重点,但应用雌激素治疗绝经后女性认知障碍的随机对照研究并未发现雌激素疗法可以改善认知功能,甚至可能会加重认知损伤[18-20],提示绝经后女性认知功能的损害还存在其他机制。

月经是女性体内铁元素丢失的重要途径,绝经后女性的血清铁蛋白水平增加2~3倍,提示体内铁储存增加,过多的铁在脑内沉积会引起脑组织铁过载,亚铁离子通过芬顿反应导致脑内细胞发生铁死亡[6, 21]。少突胶质细胞前体细胞(oligodendrocyte progenitor cell,OPC)分化的少突胶质细胞的成熟和稳定对于维持和修复髓鞘完整性至关重要,但OPC缺乏谷胱甘肽还原酶,对氧化应激较其他脑细胞更敏感[22-23]。有研究表明OPC发生铁死亡可引起脑白质损伤[24],本团队前期研究观察到脑白质损伤与老年女性认知功能下降显著相关[25],提示铁过载可损伤脑白质进而损害绝经后女性的认知功能。血清铁是与转铁蛋白结合的铁,其浓度反映了机体吸收铁和储存铁释放的状况。文献报道认知障碍患者的血清铁水平更低,考虑可能与较多的铁离子进入细胞内形成不稳定铁池有关[26-27]。本研究中有认知障碍的绝经后女性血清铁水平较低,但与无认知障碍的绝经后女性比较差异无统计学意义。今后需进一步扩大样本量,并结合转铁蛋白饱和度、铁蛋白和铁调素等铁代谢相关指标整体分析其与绝经后女性认知功能的关系。

铁死亡主要是由细胞内脂质ROS生成与降解的平衡失调所致。人体最具特征的抗氧化防御系统是Xc-系统-GSH-GPX4轴[28]。Xc-系统是一种膜蛋白,以1∶1摄入胱氨酸并排出谷氨酸。摄入的胱氨酸被还原为半胱氨酸后参与GSH合成并维持细胞内GSH含量。GPX4则通过GSH抑制脂质过氧化,是铁死亡的核心调控蛋白[11]。GSH耗竭是细胞发生铁死亡的重要原因之一,因此多通过检测GSH水平及其代谢指标监测铁死亡过程。研究显示,发生铁死亡的组织和细胞中Xc-系统功能被抑制,GSH减少,GPX4活性降低[11, 29]。而Shen等[24]发现体外培养的原代OPC发生铁死亡时,随着ROS积累,GPX4活性先代偿性升高后迅速下降,提示在病程的不同阶段,铁死亡代谢产物水平可能不同。目前铁死亡研究主要是通过体外实验或基础实验,尚未正式转化到临床研究。血清Xc-系统、GPX4和GSH与绝经后女性认知障碍的关系有待大样本量的临床研究验证。

铁死亡是细胞中ROS在亚铁离子存在下氧化脂膜上多不饱和脂肪酸产生LPO引起细胞膜损伤最终造成的细胞死亡[11],可见铁死亡的发生必然存在ROS水平升高。本研究中绝经后女性血清ROS水平升高,而绝经后认知障碍女性的血清ROS水平升高更明显,提示其氧化应激损伤更严重。细胞膜磷脂过氧化在铁死亡过程中发挥核心作用,ACSL4是人体内脂肪代谢的关键酶之一,可能通过激活多不饱和脂肪酸等途径驱动细胞发生铁死亡[30-31]。MDA是铁死亡过程中磷脂过氧化物分解代谢的脂质过氧化终末产物,Van Coillie等[32]发现血清铁和MDA水平与多器官功能衰竭患者死亡风险呈正相关,并通过基础实验推测过量脂质过氧化引起铁死亡进而导致多器官功能衰竭模型小鼠预后不良。本研究中绝经后认知障碍的女性血清ROS、ACSL4、MDA及LPO水平均升高,提示该类人群可能存在更严重的脂质过氧化反应和铁死亡过程。

本研究结果显示,绝经后认知障碍女性的受教育年限短于绝经后无认知障碍的女性,提示提高受教育水平或许可以预防女性绝经后认知障碍的发生。本研究结果显示血清GSH水平也与绝经后女性认知障碍的发生有关。ROC曲线分析结果显示受教育年限与血清GSH联合诊断认知障碍的AUC值为0.764,灵敏度为0.750,特异度为0.676,对绝经后女性认知障碍有潜在的预测价值。

综上所述,绝经后女性血清铁死亡相关指标Xc-系统、GPX4、GSH、ACSL4、ROS、LPO及MDA水平升高,其中GSH与绝经后女性认知障碍发生有关。血清GSH与受教育年限联合有望成为绝经后女性认知障碍早期诊断的潜在标志物。

本研究存在如下不足:(1)研究设计为单中心回顾性病例对照研究,样本量小,代表性不足;(2)仅探讨了血清铁死亡相关指标与绝经后女性这一特殊人群认知障碍的关系,未分析认知障碍的病因,且未深入研究铁死亡与认知障碍的相互作用机制;(3)入组女性是神经内科门诊和住院患者,且部分患者临床资料不全,可能会对结果产生影响;(4)仅研究了血清中的铁死亡相关指标,由于存在血脑屏障的影响,这些指标在脑脊液中的表达水平与外周血可能有所不同。有研究报道脑脊液铁蛋白水平升高与阿尔茨海默病患者认知功能下降及海马萎缩有关[33],但尚未见有关脑脊液铁死亡相关指标与认知障碍研究的报道。因此,本研究结果尚需在今后的临床和基础实验研究中进一步证实。

| [1] |

BATTLE D E. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM)[J]. Codas, 2013, 25(2): 191-192. DOI:10.1590/s2317-17822013000200017 |

| [2] |

PERNA L, WAHL H W, MONS U, et al. Cognitive impairment, all-cause and cause-specific mortality among non-demented older adults[J]. Age Ageing, 2015, 44(3): 445-451. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afu188 |

| [3] |

GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019[J]. Lancet Public Health, 2022, 7(2): e105-e125. DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8 |

| [4] |

CONDE D M, VERDADE R C, VALADARES A L R, et al. Menopause and cognitive impairment: a narrative review of current knowledge[J]. World J Psychiatry, 2021, 11(8): 412-428. DOI:10.5498/wjp.v11.i8.412 |

| [5] |

TAKAHASHI T A, JOHNSON K M. Menopause[J]. Med Clin North Am, 2015, 99: 521-534. DOI:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.006 |

| [6] |

ZACHARSKI L R, ORNSTEIN D L, WOLOSHIN S, et al. Association of age, sex, and race with body iron stores in adults: analysis of NHANES Ⅲ data[J]. Am Heart J, 2000, 140(1): 98-104. DOI:10.1067/mhj.2000.106646 |

| [7] |

STOCKWELL B R, FRIEDMANN ANGELI J P, BAYIR H, et al. Ferroptosis: a regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease[J]. Cell, 2017, 171(2): 273-285. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.021 |

| [8] |

MASALDAN S, BUSH A I, DEVOS D, et al. Striking while the iron is hot: iron metabolism and ferroptosis in neurodegeneration[J]. Free Radic Biol Med, 2019, 133: 221-233. DOI:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.033 |

| [9] |

WANG F, WANG J, SHEN Y, et al. Iron dyshomeostasis and ferroptosis: a new Alzheimer's disease hypothesis?[J]. Front Aging Neurosci, 2022, 14: 830569. DOI:10.3389/fnagi.2022.830569 |

| [10] |

BAO W D, PANG P, ZHOU X T, et al. Loss of ferroportin induces memory impairment by promoting ferroptosis in Alzheimer's disease[J]. Cell Death Differ, 2021, 28(5): 1548-1562. DOI:10.1038/s41418-020-00685-9 |

| [11] |

STOCKWELL B R. Ferroptosis turns 10: emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic applications[J]. Cell, 2022, 185(14): 2401-2421. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.003 |

| [12] |

NASREDDINE Z S, PHILLIPS N A, BÉDIRIAN V, et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2005, 53(4): 695-699. DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x |

| [13] |

SULLIVAN MITCHELL E, FUGATE WOODS N. Midlife women's attributions about perceived memory changes: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study[J]. J Womens Health Gend Based Med, 2001, 10(4): 351-362. DOI:10.1089/152460901750269670 |

| [14] |

WOODS N F, MITCHELL E S, ADAMS C. Memory functioning among midlife women: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study[J]. Menopause, 2000, 7(4): 257-265. |

| [15] |

LANGA K M, LEVINE D A. The diagnosis and management of mild cognitive impairment: a clinical review[J]. JAMA, 2014, 312(23): 2551-2561. DOI:10.1001/jama.2014.13806 |

| [16] |

SONG M, WANG Y M, WANG R, et al. Prevalence and risks of mild cognitive impairment of Chinese community-dwelling women aged above 60 years: a cross-sectional study[J]. Arch Womens Ment Health, 2021, 24(6): 903-911. DOI:10.1007/s00737-021-01137-0 |

| [17] |

JIA J, ZHOU A, WEI C, et al. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and its etiological subtypes in elderly Chinese[J]. Alzheimers Dement, 2014, 10(4): 439-447. DOI:10.1016/j.jalz.2013.09.008 |

| [18] |

SAVOLAINEN-PELTONEN H, RAHKOLA-SOISALO P, HOTI F, et al. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of Alzheimer's disease in Finland: nationwide case-control study[J]. BMJ, 2019, 364: l665. DOI:10.1136/bmj.l665 |

| [19] |

ESPELAND M A, RAPP S R, MANSON J E, et al. Long-term effects on cognitive trajectories of postmenopausal hormone therapy in two age groups[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2017, 72(6): 838-845. DOI:10.1093/gerona/glw156 |

| [20] |

GLEASON C E, DOWLING N M, WHARTON W, et al. Effects of hormone therapy on cognition and mood in recently postmenopausal women: findings from the randomized, controlled KEEPS-cognitive and affective study[J]. PLoS Med, 2015, 12(6): e1001833. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001833 |

| [21] |

谷正盛, 杜冰滢, 吴汶, 等. 中枢神经系统铁沉积与血管性认知障碍研究进展[J]. 海军军医大学学报, 2022, 43(3): 301-307. GU Z S, DU B Y, WU W, et al. Iron deposition in central nervous system and vascular cognitive impairment: research progress[J]. Acad J Naval Med Univ, 2022, 43(3): 301-307. DOI:10.16781/j.CN31-2187/R.20220102 |

| [22] |

KUHN S, GRITTI L, CROOKS D, et al. Oligodendrocytes in development, myelin generation and beyond[J]. Cells, 2019, 8(11): 1424. DOI:10.3390/cells8111424 |

| [23] |

VAN TILBORG E, HEIJNEN C J, BENDERS M J, et al. Impaired oligodendrocyte maturation in preterm infants: potential therapeutic targets[J]. Prog Neurobiol, 2016, 136: 28-49. DOI:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.11.002 |

| [24] |

SHEN D, WU W, LIU J, et al. Ferroptosis in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells mediates white matter injury after hemorrhagic stroke[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2022, 13(3): 259. DOI:10.1038/s41419-022-04712-0 |

| [25] |

殷歌, 孙瑞, 梁萌, 等. 血清25-羟维生素D和催乳素与脑白质损伤老年女性患痴呆风险的相关性[J]. 海军军医大学学报, 2022, 43(2): 123-129. YIN G, SUN R, LIANG M, et al. Association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and prolactin levels with the risk of dementia in elderly women with white matter lesions[J]. Acad J Naval Med Univ, 2022, 43(2): 123-129. DOI:10.16781/j.CN31-2187/R.20220085 |

| [26] |

KWEON O J, YOUN Y C, LIM Y K, et al. Clinical utility of serum hepcidin and iron profile measurements in Alzheimer's disease[J]. J Neurol Sci, 2019, 403: 85-91. DOI:10.1016/j.jns.2019.06.008 |

| [27] |

RAHA A A, GHAFFARI S D, HENDERSON J, et al. Hepcidin increases cytokines in Alzheimer's disease and Down's syndrome dementia: implication of impaired iron homeostasis in neuroinflammation[J]. Front Aging Neurosci, 2021, 13: 653591. DOI:10.3389/fnagi.2021.653591 |

| [28] |

BANNAI S, KITAMURA E. Transport interaction of L-cystine and L-glutamate in human diploid fibroblasts in culture[J]. J Biol Chem, 1980, 255(6): 2372-2376. |

| [29] |

KWON H K, KIM J M, SHIN S C, et al. The mechanism of submandibular gland dysfunction after menopause may be associated with the ferroptosis[J]. Aging (Albany NY), 2020, 12(21): 21376-21390. DOI:10.18632/aging.103882 |

| [30] |

DOLL S, PRONETH B, TYURINA Y Y, et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition[J]. Nat Chem Biol, 2017, 13(1): 91-98. DOI:10.1038/nchembio.2239 |

| [31] |

ZHANG H L, HU B X, LI Z L, et al. PKCβⅡ phosphorylates ACSL4 to amplify lipid peroxidation to induce ferroptosis[J]. Nat Cell Biol, 2022, 24(1): 88-98. DOI:10.1038/s41556-021-00818-3 |

| [32] |

VAN COILLIE S, VAN SAN E, GOETSCHALCKX I, et al. Targeting ferroptosis protects against experimental (multi)organ dysfunction and death[J]. Nat Commun, 2022, 13(1): 1046. DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-28718-6 |

| [33] |

DIOUF I, FAZLOLLAHI A, BUSH A I, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid ferritin levels predict brain hypometabolism in people with underlying β-amyloid pathology[J]. Neurobiol Dis, 2019, 124: 335-339. DOI:10.1016/j.nbd.2018.12.010 |

2024, Vol. 45

2024, Vol. 45