2. 海军军医大学(第二军医大学)转化医学中心临床肿瘤研究所,上海 200433

2. Clinical Cancer Institute, Center of Translational Medicine, Naval Medical University (Second Military Medical University), Shanghai 200433, China

肝癌是威胁人类健康的主要恶性肿瘤之一。对GLOBOCAN 2020[1]数据的二次分析显示,2020年中国肝癌新发病例约为41万例,位居中国恶性肿瘤发病第5位,而死亡病例约为39.1万例,位居中国癌症相关死亡原因第2位[2]。肝细胞癌(hepatocellular carcinoma,HCC)是肝癌的主要病理类型,其治疗手段包括手术切除、肿瘤消融、肝移植等局部疗法,靶向治疗、免疫治疗等全身疗法,手术切除、消融等手段是潜在的治愈疗法,但多限于早期HCC患者,且几乎70%的患者会复发[3]。大部分HCC患者发现时已处于中晚期,不具备手术指征,需通过全身疗法延缓病情进展[4]。索拉非尼是第1个被批准用于晚期HCC一线全身治疗的靶向药物,是晚期HCC患者的标准疗法,能够延长晚期HCC患者的中位生存期,然而许多HCC患者在接受数月的索拉非尼治疗后出现耐药,导致临床获益受限[5-6]。目前,索拉非尼耐药的具体机制尚不明确,涉及MAPK14信号、肿瘤启动细胞的富集和胰岛素样生长因子/成纤维细胞生长因子信号的重激活等[7],尚缺乏有效的疗效预测指标。本研究应用生物信息学技术筛选HCC索拉非尼耐药相关基因并构建预后模型,为预测HCC的预后及索拉非尼敏感性提供依据。

1 资料和方法 1.1 数据收集从基因表达汇编(Gene Expression Omnibus,GEO)数据库GSE109211数据集[8]下载索拉非尼治疗队列的转录组测序数据和相关临床信息(包含67例索拉非尼治疗患者)。从癌症基因组图谱(The Cancer Genome Atlas,TCGA)数据库(https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/)LIHC(TCGA-LIHC)队列下载377例HCC患者转录组测序数据和相对应的临床信息数据。从基因型组织表达(Genotype-Tissue Expression Consortium,GTEx)数据库下载正常人肝组织样本的转录组测序数据。从国际肿瘤基因组协作组(International Cancer Genome Consortium,ICGC)数据库(https://dcc.icgc.org/)LIRI(ICGC-LIRI)队列下载243例HCC患者(240例为原发HCC,3例为转移HCC)肿瘤样本转录组测序数据和临床信息数据。利用Sangerbox 3.0(http://sangerbox.com/home.html)对下载的转录组测序数据进行清洗,去除重复样本,并对原始数据进行log2(X+1)标准化处理。差异基因分析样本纳入标准:(1)诊断为HCC;(2)转录组表达数据无缺失。最终获得来自TCGA-LIHC队列的371例肿瘤样本和来自GTEx数据库的276例正常肝组织样本,以及来自于ICGC-LIRI队列的240例原发HCC肿瘤样本和202例正常肝组织样本。预后模型构建样本纳入标准:(1)原发疾病诊断为HCC;(2)生存资料完整。在剔除无相关信息的患者后,TCGA-LIHC队列中有368例HCC患者被纳入训练集,ICGC-LIRI队列中的243例HCC患者被纳入验证集。

1.2 HCC索拉非尼敏感性相关基因的获取与分析使用R4.3.0软件limma包[9]分析GSE109211队列中索拉非尼敏感组和耐受组之间的差异表达基因,P值经Benjamini-Hochberg(BH)法校正,设置校正后P<0.05筛选出与索拉非尼敏感性相关的基因。使用R4.3.0软件limma包[9]识别TCGA-LIHC和ICGC-LIRI队列中肿瘤组织与正常肝组织之间的差异表达基因,P值用BH法校正,设置校正后P<0.05和|log2FC|>1(FC为差异倍数,fold change)筛选出差异表达基因。将3个队列的差异表达基因利用R4.3.0软件VennDiagram包[10]绘制维恩图并获取交集基因。采用R4.3.0软件clusterProfiler包[11]对交集基因进行京都基因与基因组百科全书(Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes,KEGG)通路富集分析,用BH法校正P值。

1.3 基于索拉非尼敏感性基因的HCC预后模型的建立与验证通过R4.3.0软件survival包对上述交集基因在TCGA-LIHC队列中进行单因素Cox回归分析,设置P<0.05筛选出与样本生存显著相关的基因。以TCGA-LIHC队列为训练集,基于上述候选基因使用R4.3.0软件glmnet包进行最小绝对收缩和选择算子(least absolute shrinkage and selection operator,LASSO)回归分析[12-13],以减少过拟合的可能性。在惩罚参数λ为0.061时,基于7个与索拉非尼敏感性和预后相关的基因构建风险模型。风险评分为7个基因表达量与回归系数乘积之和,将样本按照风险评分的中位值分为高、低风险组。以ICGC-LIRI队列为验证集,采用同样的方法计算验证集中每个样本的风险得分并进行分组。利用R4.3.0软件prcomp函数对训练集和验证集进行主成分分析(principal component analysis,PCA)并通过R4.3.0软件ggplot2包[14]进行可视化以探索不同组别的分布情况。在训练集和验证集中通过R4.3.0软件survminer包和timeROC包分别绘制Kaplan-Meier生存曲线和ROC曲线,评估该模型的预测能力。绘制热图分析风险评分和临床病理特征(年龄、性别、临床分期)与生存结局的相关性,绘制小提琴图评价风险评分与生存结局、组织病理学分级、T分期、临床分期等的相关性。在TCGA-LIHC、ICGC-LIRI队列中,纳入临床病理特征和风险评分进行单因素和多因素Cox回归分析,筛选预后的独立危险因素。

1.4 索拉非尼敏感性分析用于拟合的数据来自癌症药物敏感性基因组学(Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer,GDSC)数据库(https://www.cancerrxgene.org/)GDSC1和GDSC2数据集。通过R4.3.0软件Oncopredict包[15]根据基因表达水平预测TCGA-LIHC队列中每例患者的药物敏感性,获得索拉非尼的IC50,比较高风险组与低风险组IC50的差异。

1.5 统计学处理所有数据的可视化和统计分析均通过R4.3.0软件完成。两组之间计量资料的比较采用独立样本t检验,多组之间计量资料的比较采用单因素方差分析;计数资料的比较采用χ2检验。两个变量之间的相关性采用Spearman相关分析。单因素生存分析采用Kaplan-Meier法和log-rank检验,多变量生存分析采用Cox回归分析。检验水准(α)为0.05。

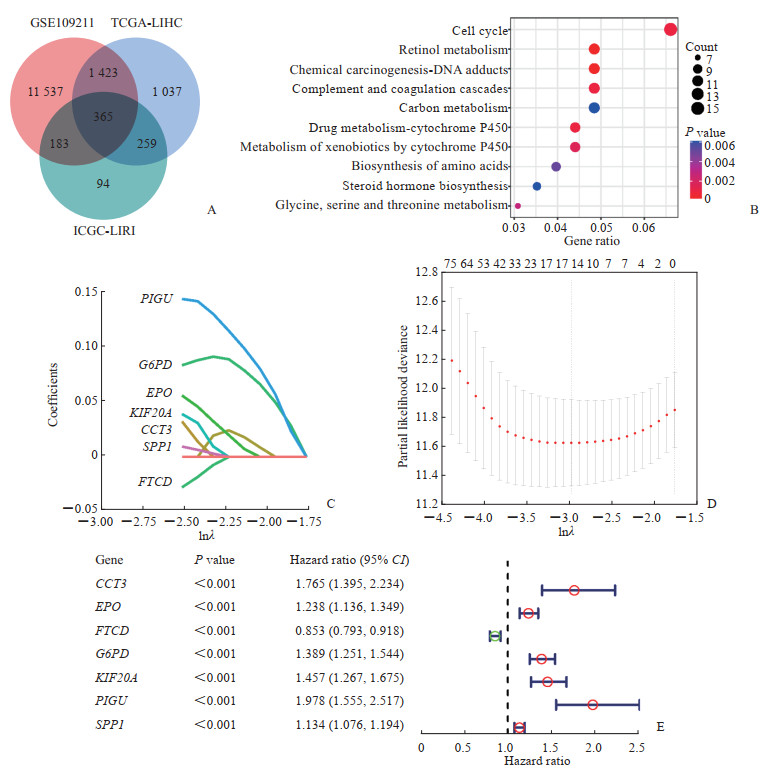

2 结果 2.1 基于索拉非尼敏感性相关基因的HCC预后模型的构建从GEO数据库GSE109211数据集筛选出与索拉非尼敏感性相关的差异基因,在TCGA-LIHC和ICGC-LIRI队列中鉴定出正常肝组织和肿瘤组织的差异表达基因,将两者进行交集,获得365个基因(图 1A)。KEGG富集分析显示这些基因与药物代谢和癌症发生等相关(图 1B),说明筛选出的基因与HCC的发生和索拉非尼的敏感性相关。通过单因素Cox回归分析上述365个基因在TCGA-LIHC队列中与总生存期之间的相关性,获得221个与HCC预后相关候选基因。以TCGA-LIHC队列为训练集,基于这些候选基因进行LASSO回归分析构建模型,根据最小准则确定的惩罚参数λ得到含TCP1伴侣蛋白亚单位3(chaperonin containing TCP1 subunit 3,CCT3)、红细胞生成素(erythropoietin,EPO)、甲酰转移酶环脱氨酶(formimidoyltransferase cyclodeaminase,FTCD)、葡萄糖-6-磷酸脱氢酶(glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase,G6PD)、驱动蛋白家族成员20A(kinesin family member 20A,KIF20A)、磷脂酰肌醇聚糖锚定生物合成U类基因(phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis class U,PIGU)、分泌型磷蛋白1(secreted phosphoprotein 1,SPP1)7个关键基因(图 1C、1D),其中FTCD为保护因素,而CCT3、EPO、G6PD、KIF20A、PIGU、SPP1为危险因素(图 1E)。

|

图 1 HCC索拉非尼敏感性相关基因的筛选及预后模型构建 Fig 1 Screening of sorafenib sensitivity-related genes and construction of prognostic model in HCC A: Venn diagram to identify differentially expressed genes correlated with sorafenib sensitivity between tumor and adjacent normal tissue. B: Bubble diagram of the top 10 terms in Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes enrichment analysis of the differentially expressed genes. C: LASSO coefficient profiles of the expression of the candidate genes. D: Selection of the penalty parameter (λ) in the LASSO model via 10-fold cross-validation. The optimal λ value is 0.061. E: Univariate Cox regression analysis of 7 key genes in the TCGA-LIHC cohort. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; LASSO: Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas; ICGC: International Cancer Genome Consortium; PIGU: Phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis class U; G6PD: Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; EPO: Erythropoietin; KIF20A: Kinesin family member 20A; CCT3: Chaperonin containing TCP1 subunit 3; SPP1: Secreted phosphoprotein 1; FTCD: Formimidoyltransferase cyclodeaminase; CI: Confidence interval. |

2.2 基于索拉非尼敏感性基因的HCC预后模型的评价和验证

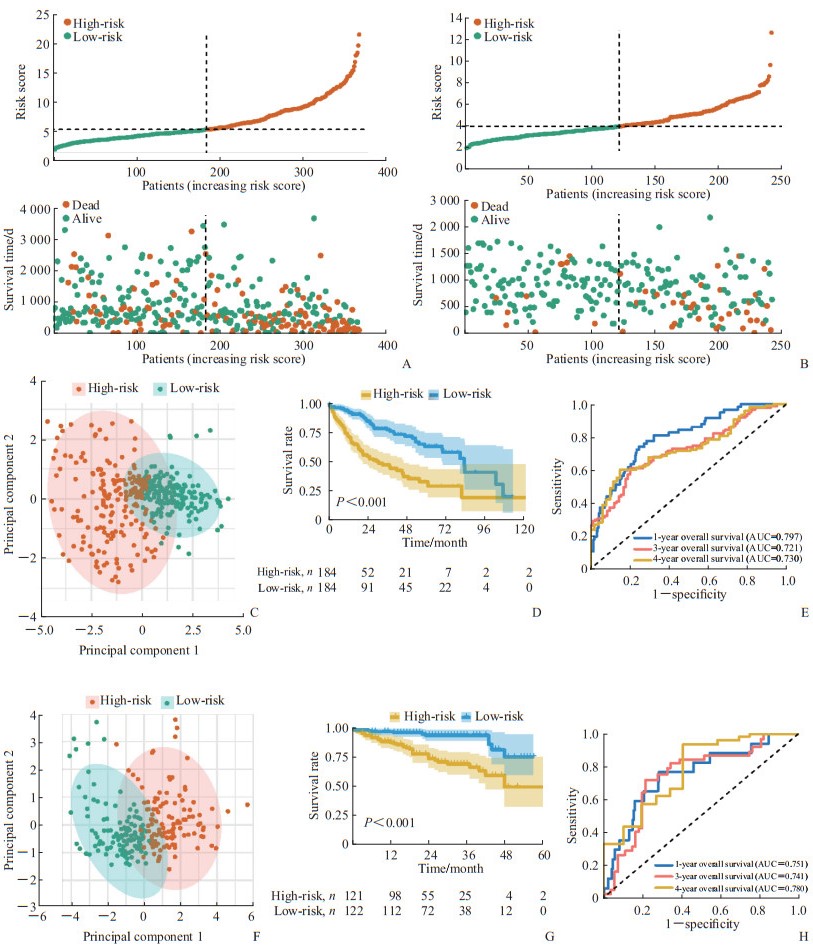

计算训练集、验证集的风险评分,依据中位值将样本分为高、低风险组(图 2A、2B),PCA分析显示训练集的高、低风险组呈不同方向分布(图 2C)。在训练集中,与低风险组相比,高风险组患者总生存期更短(P<0.002,图 2D);同时,采用ROC曲线评价风险评分对总生存期的预测性能,预测1、3、4年总生存期的AUC分别为0.797、0.721、0.730(图 2E)。与训练集结果相似,验证集的高、低风险组在PCA上也呈现为不同的方向(图 2F),高风险组的生存期短于风险组(P<0.001,图 2G),风险评分预测1、3、4年总生存期的AUC分别为0.751、0.741、0.780(图 2H)。

|

图 2 基于索拉非尼敏感性相关基因的HCC预后模型的评价 Fig 2 Evaluation of prognostic model based on sorafenib sensitivity-related genes in HCC A: The risk score distribution and patient survival status in the TCGA-LIHC cohort were depicted in ranked dot and scatter plots; B: The risk score distribution and patient survival status in the ICGC-LIRI cohort were depicted in ranked dot and scatter plots; C: PCA plot of the TCGA-LIHC cohort; D: Kaplan-Meier curves for the overall survival of patients between the high-risk group and low-risk group in the TCGA-LIHC cohort; E: AUC of time-dependent ROC curves verified the prognostic performance of the risk score in the TCGA-LIHC cohort; F: PCA plot of the ICGC-LIRI cohort; G: Kaplan-Meier curves for the overall survival of patients between the high-risk group and low-risk group in the ICGC-LIRI cohort; H: AUC of time-dependent ROC curves verified the prognostic performance of the risk score in the ICGC-LIRI cohort. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas; ICGC: International Cancer Genome Consortium; PCA: Principal component analysis; AUC: Area under curve; ROC: Receiver operating characteristic. |

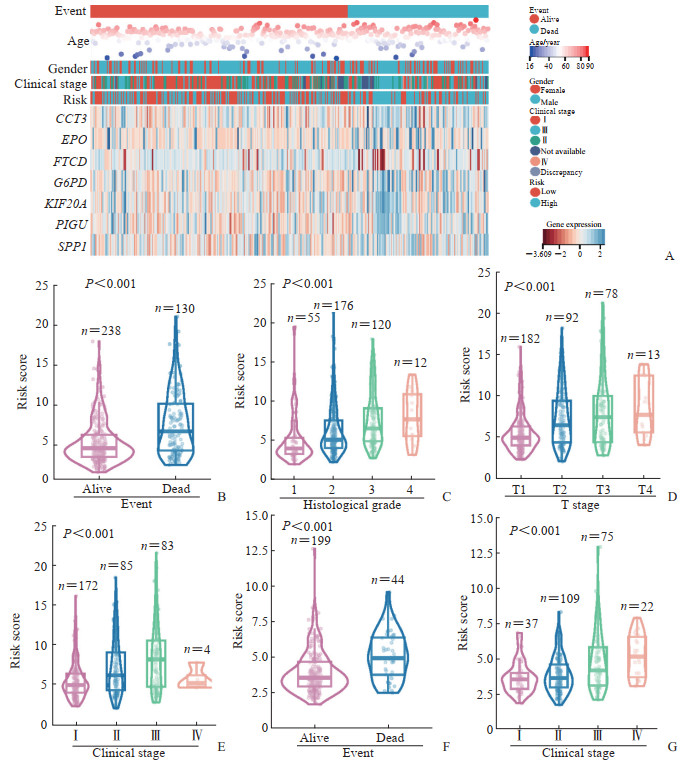

生存分析结果显示,死亡的HCC患者多属于高风险组,并且CCT3、EPO、G6PD、KIF20A、PIGU、SPP1基因的表达水平较高,而FTCD基因的表达水平较低(图 3A)。风险评分与年龄和性别无关,而发生死亡事件、组织病理学分级较高及临床分期为晚期的患者风险评分较高(图 3B~3E),并且死亡事件的发生和临床分期与风险评分的关系在验证集中获得一致的结论(图 3F、3G)。对可用变量进行单因素和多因素Cox回归分析,单因素Cox回归分析显示,在TCGA-LIHC和ICGC-LIRI队列中低风险评分为总生存期的保护因素(HR=0.34,95% CI 0.24~0.50,P<0.001;HR=0.24,95% CI 0.12~0.48,P<0.001);多因素Cox回归分析显示,在TCGA-LIHC队列和ICGC-LIRI中低风险评分为总生存期的独立保护因素(HR=0.40,95% CI 0.27~0.59,P<0.001;HR=0.29,95% CI 0.14~0.60,P<0.001)。因此,风险评分对HCC患者预后具有独立的预测价值。

|

图 3 基于索拉非尼敏感性基因的HCC预后模型风险评分与临床特征的关系 Fig 3 Relationship between clinicopathological features and risk scores of HCC prognostic model based on sorafenib sensitivity-related genes in HCC A: Heatmap of prognostic and clinicopathological features of 7 sorafenib sensitivity-related genes in 2 risk subgroups; B-E: Associations between the risk scores and clinicopathological features, including event (B), histological grade (C), clinical stage (D) and T stage (E) in the TCGA-LIHC cohort; F, G: Associations between the risk scores and clinicopathological features, including event (F) and clinical stage (G) in the ICGC-LIRI cohort. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas; ICGC: International Cancer Genome Consortium. |

2.3 基于索拉非尼敏感性的HCC预后

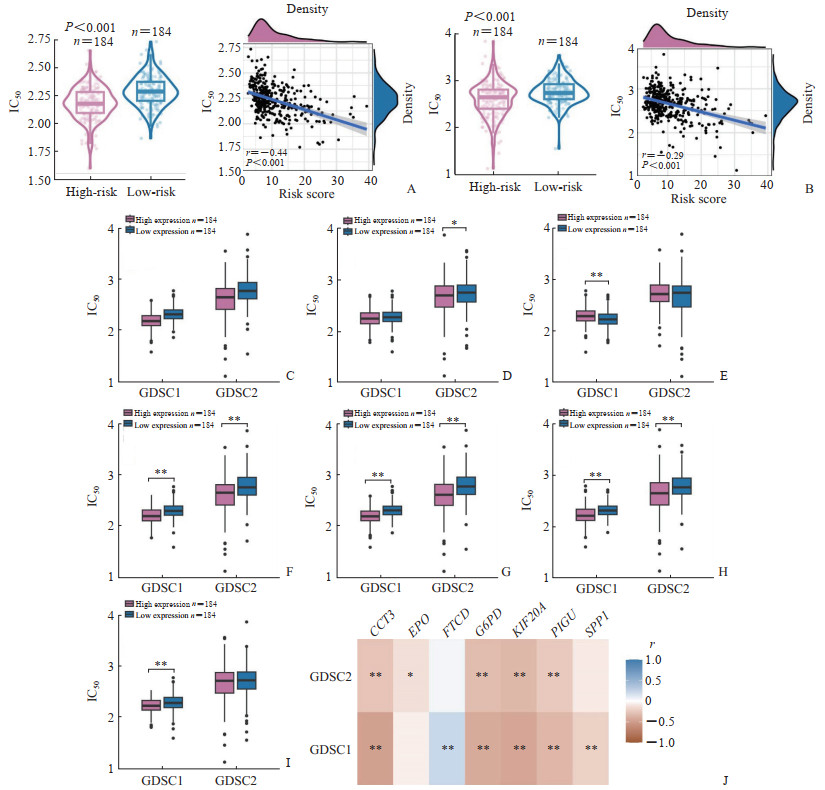

结果显示不论在GDSC1还是GDSC2数据集中,高风险组的索拉非尼IC50均低于低风险组,风险评分与索拉非尼的IC50呈负相关(图 4A、4B),说明高风险评分的患者对索拉非尼更敏感。将患者依据7个关键基因表达中位值分为高、低表达组,其中6个基因的高表达组与低表达组之间索拉非尼的IC50存在明显差异(图 4C~4I)。相关性分析结果显示,7个关键基因的表达水平均与索拉非尼的IC50相关,其中CCT3、EPO、G6PD、KIF20A、PIGU、SPP1表达水平与索拉非尼的IC50呈负相关,而FTCD表达水平与索拉非尼的IC50呈正相关(图 4J)。以上数据表明,该模型可以预测HCC患者对索拉非尼的敏感性。

|

图 4 基于索拉非尼敏感性相关基因的HCC预后模型与HCC中索拉非尼IC50的关系 Fig 4 Relationship between sorafenib IC50 and prognostic model based on sorafenib sensitivity-related genes in HCC A: Analysis of correlations between risk scores and sorafenib IC50 of GDSC1 database in the TCGA-LIHC cohort; B: Analysis of correlations between risk scores and sorafenib IC50 of GDSC2 database in the TCGA-LIHC cohort; C-I: The influence on the sorafenib IC50 of CCT3 (C), EPO (D), FTCD (E), G6PD (F), KIF20A (G), PIGU (H) and SPP1 (I) expression; J: The correlations between the sorafenib IC50 and the expression of CCT3, EPO, FTCD, G6PD, KIF20A, PIGU and SPP1. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; IC50: Half inhibitory concentration; GDSC: Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer; CCT3: Chaperonin containing TCP1 subunit 3; EPO: Erythropoietin; FTCD: Formimidoyltransferase cyclodeaminase; G6PD: Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; KIF20A: Kinesin family member 20A; PIGU: Phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis class U; SPP1: Secreted phosphoprotein 1. |

3 讨论

本研究通过GEO、TCGA和ICGC数据库筛选出365个在HCC中差异表达且与索拉非尼敏感性相关的基因,通过单因素Cox回归和LASSO回归分析,构建了包含7个关键基因(CCT3、EPO、FTCD、G6PD、KIF20A、PIGU、SPP1)的预后模型,有望为临床个体化治疗HCC提供理论依据。

CCT3是分子伴侣家族的重要成员,参与多种恶性肿瘤的发展与侵袭过程,在HCC中能够启动肿瘤细胞的转录和增殖[16]。EPO的主要功能是刺激红细胞生成,研究发现EPO与其受体在乳腺癌、膀胱癌中能够促进肿瘤细胞的增殖和恶性表型[17-18]。FTCD是一种双功能酶,有研究表明,FTCD的过表达能够抑制HCC细胞的增殖并促进其凋亡[19]。G6PD是磷酸戊糖途径的第1个限速酶,在多种代谢过程中发挥重要作用。G6PD在多种肿瘤中表达上调,并且与癌细胞的转化、转移及药物耐药等过程相关[20]。另有研究发现在索拉非尼耐药的细胞中G6PD的表达下调,与耐药细胞对葡萄糖需求增高从而抑制葡萄糖进入磷酸戊糖途径相关[21]。KIF20A是驱动蛋白超家族的成员,能够调节细胞有丝分裂。KIF20A几乎在所有肿瘤中高表达,可能是一种预后标志物。在乳腺癌、前列腺癌和结直肠癌中,KIF20A能够促进肿瘤细胞耐药[22]。在HCC中,有研究者发现KIF20A敲低能够抑制HCC细胞增殖并增强其对顺铂和索拉非尼的敏感性[23]。PIGU是糖基磷脂酰肌醇转氨酶(glycosylphosphatidylinositol transamidase,GPI-T)复合物的重要亚基,参与糖基磷脂酰肌醇中长链脂肪酸的识别,并通过增加GPI-T的活性促进癌症进展。在HCC中,PIGU通过NF-κB信号通路促进肝细胞活力、细胞周期进程、迁移和侵袭,并抑制细胞凋亡[24]。SPP1又称骨桥蛋白,在与癌症发展相关的慢性炎症期间调节宿主免疫、促进肿瘤增殖、抑制肿瘤细胞凋亡,与多种肿瘤预后不良相关[25]。有证据表明,SPP1的表达在某些癌种中与化疗耐药性相关[26]。本研究结果与上述研究基本一致,除了FTCD为HCC预后的保护因素外,其余6个关键基因均为HCC预后的危险因素。

为进一步探索预后模型在HCC中的应用,本研究分析了训练集TCGA-LIHC队列和验证集ICGC-LIRI队列中风险评分对HCC患者预后的影响,结果表明,与低风险组的患者相比,高风险组患者的总生存期短,并且风险评分与临床分期和组织病理学分级等临床特征相关,是HCC的独立预后因素,提示该模型对HCC患者的预后具有一定的预测能力。由于这些基因是基于对索拉非尼治疗的反应性筛选出来的,本研究还利用GDSC数据库中的药物IC50信息预测了TCGA-LIHC队列HCC患者对索拉非尼的敏感性,探索了不同风险分组与索拉非尼IC50的关系,结果显示高风险组的HCC患者有较低的IC50,表明高风险组的患者可能对索拉非尼更加敏感。

综上所述,本研究基于CCT3、EPO、FTCD、G6PD、KIF20A、PIGU、SPP1基因构建的预后模型对HCC患者的预后及索拉非尼敏感性具有一定的预测能力。虽然生物信息学结果显示这些基因与索拉非尼敏感性相关,但大部分基因与索拉非尼耐药的关系还未见报道,值得进一步探索。本研究的局限在于所有分析是建立在生物信息学基础上的,缺少相关分子生物学实验的验证,后续本课题组将开展相关实验工作,进一步探索关键基因与索拉非尼耐药的关系及机制,并评估该模型在HCC的风险分层、预后评价和疗效评估等方面的作用。

| [1] |

SUNG H, FERLAY J, SIEGEL R L, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3): 209-249. DOI:10.3322/caac.21660 |

| [2] |

CAO W, CHEN H D, YU Y W, et al. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: a secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020[J]. Chin Med J, 2021, 134(7): 783-791. DOI:10.1097/CM9.0000000000001474 |

| [3] |

YANG J D, HAINAUT P, GORES G J, et al. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019, 16(10): 589-604. DOI:10.1038/s41575-019-0186-y |

| [4] |

CASAK S J, DONOGHUE M, FASHOYIN-AJE L, et al. FDA approval summary: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab for the treatment of patients with advanced unresectable or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2021, 27(7): 1836-1841. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3407 |

| [5] |

HUANG A, YANG X R, CHUNG W Y, et al. Targeted therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2020, 5(1): 146. DOI:10.1038/s41392-020-00264-x |

| [6] |

KULIK L, EL-SERAG H B. Epidemiology and management of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Gastroenterology, 2019, 156(2): 477-491.e1. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.065 |

| [7] |

LLOVET J M, ZUCMAN-ROSSI J, PIKARSKY E, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2016, 2: 16018. DOI:10.1038/nrdp.2016.18 |

| [8] |

PINYOL R, MONTAL R, BASSAGANYAS L, et al. Molecular predictors of prevention of recurrence in HCC with sorafenib as adjuvant treatment and prognostic factors in the phase 3 STORM trial[J]. Gut, 2019, 68(6): 1065-1075. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316408 |

| [9] |

RITCHIE M E, PHIPSON B, WU D, et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies[J]. Nucleic Acids Res, 2015, 43(7): e47. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkv007 |

| [10] |

CHEN H, BOUTROS P C. VennDiagram: a package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R[J]. BMC Bioinformatics, 2011, 12: 35. DOI:10.1186/1471-2105-12-35 |

| [11] |

YU G, WANG L G, HAN Y, et al. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters[J]. OMICS, 2012, 16(5): 284-287. DOI:10.1089/omi.2011.0118 |

| [12] |

GAO J, KWAN P W, SHI D. Sparse kernel learning with LASSO and Bayesian inference algorithm[J]. Neural Netw, 2010, 23(2): 257-264. DOI:10.1016/j.neunet.2009.07.001 |

| [13] |

FRIEDMAN J, HASTIE T, TIBSHIRANI R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent[J]. J Stat Softw, 2010, 33(1): 1-22. DOI:10.18637/jss.v033.i01 |

| [14] |

ITO K, MURPHY D. Application of ggplot2 to pharmacometric graphics[J]. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol, 2013, 2(10): e79. DOI:10.1038/psp.2013.56 |

| [15] |

MAESER D, GRUENER R F, HUANG R S. oncoPredict: an R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data[J]. Brief Bioinform, 2021, 22(6): bbab260. DOI:10.1093/bib/bbab260 |

| [16] |

LIU W, LU Y, YAN X, et al. Current understanding on the role of CCT3 in cancer research[J]. Front Oncol, 2022, 12: 961733. DOI:10.3389/fonc.2022.961733 |

| [17] |

REINBOTHE S, LARSSON A M, VAAPIL M, et al. EPO-independent functional EPO receptor in breast cancer enhances estrogen receptor activity and promotes cell proliferation[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2014, 445(1): 163-169. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.165 |

| [18] |

PARK S L, WON S Y, SONG J H, et al. EPO gene expression induces the proliferation, migration and invasion of bladder cancer cells through the p21WAF1-mediated ERK1/2/NF-κB/MMP-9 pathway[J]. Oncol Rep, 2014, 32(5): 2207-2214. DOI:10.3892/or.2014.3428 |

| [19] |

CHEN J, YANG Y, LIN B, et al. Hollow mesoporous organosilica nanotheranostics incorporating formimidoyltransferase cyclodeaminase (FTCD) plasmids for magnetic resonance imaging and tetrahydrofolate metabolism fission on hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Int J Pharm, 2022, 612: 121281. DOI:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.121281 |

| [20] |

YANG H C, STERN A, CHIU D T Y. G6PD: a hub for metabolic reprogramming and redox signaling in cancer[J]. Biomed J, 2021, 44(3): 285-292. DOI:10.1016/j.bj.2020.08.001 |

| [21] |

YOU X, JIANG W, LU W, et al. Metabolic reprogramming and redox adaptation in sorafenib-resistant leukemia cells: detected by untargeted metabolomics and stable isotope tracing analysis[J]. Cancer Commun (Lond), 2019, 39(1): 17. DOI:10.1186/s40880-019-0362-z |

| [22] |

JIN Z, PENG F, ZHANG C, et al. Expression, regulating mechanism and therapeutic target of KIF20A in multiple cancer[J]. Heliyon, 2023, 9(2): e13195. DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13195 |

| [23] |

WU C, QI X, QIU Z, et al. Low expression of KIF20A suppresses cell proliferation, promotes chemosensitivity and is associated with better prognosis in HCC[J]. Aging, 2021, 13(18): 22148-22163. DOI:10.18632/aging.203494 |

| [24] |

WEI X, YANG W, ZHANG F, et al. PIGU promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression through activating NF-κB pathway and increasing immune escape[J]. Life Sci, 2020, 260: 118476. DOI:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118476 |

| [25] |

LAMORT A S, GIOPANOU I, PSALLIDAS I, et al. Osteopontin as a link between inflammation and cancer: the Thorax in the spotlight[J]. Cells, 2019, 8(8): 815. DOI:10.3390/cells8080815 |

| [26] |

PANG X, GONG K, ZHANG X, et al. Osteopontin as a multifaceted driver of bone metastasis and drug resistance[J]. Pharmacol Res, 2019, 144: 235-244. DOI:10.1016/j.phrs.2019.04.030 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44