2. 天津市第一中心医院风湿免疫科, 天津 300110

2. Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Tianjin First Central Hospital, Tianjin 300110, China

类风湿关节炎(rheumatoid arthritis,RA)为自身免疫性疾病,以关节肿胀压痛、疾病反复、缠绵难愈为特征。RA患者预期寿命相比健康人群缩短[1],心血管疾病尤其是冠状动脉粥样硬化性心脏病(以下简称冠心病,coronary heart disease,CHD)的发生是其不可忽视的危险因素。RA患者心血管疾病的发生风险较健康人群增加2倍[2],其危险因素除吸烟、肥胖、高脂血症、高血压、糖尿病等传统因素外,还包括RA患者特有的危险因素,如糖皮质激素、非甾体抗炎药(non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug,NSAID)、改善病情抗风湿药(disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug,DMARD)、TNF抑制剂等药物的使用[3]。同时IL-1、趋化因子及黏附因子等促炎细胞因子在内皮细胞及动脉粥样硬化病变组织中高表达也具有损害血管扩张的作用[4]。此外,动脉粥样硬化斑块新预测因子,如炎性因子新蝶呤[5],也对CHD的发生起促进作用。研究发现,RA患者慢性炎症不仅对促进粥样硬化斑块的形成发挥重要作用,并且与血脂异常、内皮功能障碍、胰岛素抵抗均有关[6],而这些均为CHD的危险因素。本研究通过回顾性分析近10年RA患者的临床及实验室指标及并发症发生情况,探究RA患者CHD患病率在不同年份和不同性别的分布情况及可能的影响因素,为RA患者临床预防和治疗CHD提供参考。

1 资料和方法 1.1 一般资料选择2009年1月1日至2019年3月20日于天津市第一中心医院就诊的RA患者5 426例,其中男1 065例,年龄为(66.70±12.34)岁;女4 361例,年龄为(62.23±13.16)岁。选择同期就诊的骨关节炎(osteoarthritis,OA)患者1 483例作为对照,其中男418例,年龄为(63.12±13.01)岁;女1 065例,年龄为(64.24±10.62)岁。纳入标准:(1)RA患者符合2010年美国风湿病学会/欧洲风湿病联盟分类标准的RA诊断标准[7],OA患者符合美国风湿病学会诊断和治疗标准中的OA诊断标准[8];(2)年龄≥18岁;(3)签署知情同意书。排除标准:(1)RA合并OA患者;(2)OA合并系统性红斑狼疮、皮肌炎等风湿免疫病患者;(3)患有恶性肿瘤及传染病者。

1.2 研究方法收集RA及OA患者的基本信息、实验室指标、CHD及其相关并发症的发生情况及药物使用情况。(1)基本信息,包括性别、年龄、身高、体重、病程。(2)实验室指标。①炎症指标:红细胞沉降率(erythrocyte sedimentation rate,ESR)、CRP。②炎性因子:白细胞介素2受体(interleukin 2 receptor,IL-2R)、IL-6、IL-8、IL-10、TNF-α和IL-1β。③脂质代谢指标:高密度脂蛋白胆固醇(high density lipoprotein-cholesterol,HDL-C)、低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(low density lipoprotein-cholesterol,LDL-C)、总胆固醇和三酰甘油。④自身抗体:类风湿因子(rheumatoid factor,RF)、免疫球蛋白A型类风湿因子(immunoglobulin A-rheumatoid factor,IgA-RF)、免疫球蛋白G型类风湿因子(immunoglobulin G-rheumatoid factor,IgG-RF)、抗环瓜氨酸肽(anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide,ACCP)和抗角蛋白抗体(anti-keratin antibody,AKA)。⑤Ig:IgA、IgG和IgM。⑥补体成分:补体3、补体4。⑦其他实验室指标:D-二聚体、纤维蛋白原(fibrinogen,FiB)、25-羟基维生素D[25-hydroxyvitamin D,25-(OH)D]、肌酸激酶、心肌型肌酸激酶同工酶(creatine kinase-myocardial band,CK-MB)、血糖、同型半胱氨酸(homocysteine,Hcy)和尿酸。(3)CHD及其相关并发症。CHD诊断标准:①冠状动脉造影确认冠状动脉至少1个主要分支狭窄≥50%,无论有无血运重建(冠状动脉旁路移植术或经皮冠状动脉介入治疗);②有心肌梗死病史,无论有无血运重建。具有①②之一即诊断CHD。并发症包括高血压、高脂血症、糖尿病。(4)使用药物包括DMARD、糖皮质激素、NSAID。将2009年1月1日至2019年3月20日分为4组:2009年1月1日至2011年12月31日、2012年1月1日至2014年12月31日、2015年1月1日至2017年12月31日、2018年1月1日至2019年3月20日,分析不同时间段CHD相关并发症的发生情况。

1.3 统计学处理应用SPSS 24.0软件进行统计学分析。呈正态分布的计量资料以x±s表示,若方差齐两组间比较采用独立样本t检验,否则采用近似t检验;呈偏态分布的计量资料以中位数(下四分位数,上四分位数)表示,两组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验。计数资料以例数和百分数表示,组间比较采用χ2检验。采用logistic回归分析RA患者合并CHD的影响因素。对RA组与OA组以年龄和性别按1:1进行倾向评分匹配;部分实验室指标存在少数缺失,分析时根据具体情况应用SPSS 24.0软件采用按列表排除个案(exclude cases listwise)或按对排除个案(exclude cases pairwise)。检验水准(α)为0.05。

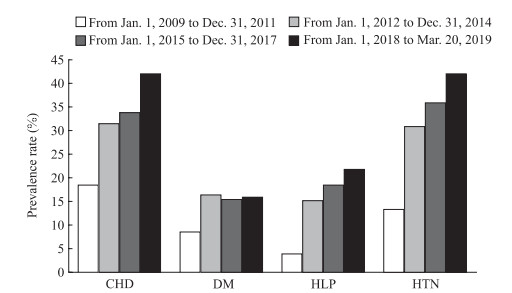

2 结果 2.1 不同性别和年份RA患者CHD及其相关并发症的发生率男性、女性RA患者CHD患病率分别为32.1%(321/1 000)、32.3%(323/1 000),差异无统计学意义(χ2=0.02,P=0.90)。见图 1,2009年1月1日至2011年12月31日、2012年1月1日至2014年12月31日、2015年1月1日至2017年12月31日和2018年1月1日至2019年3月20日4个时间段,RA患者CHD[分别为18.6%(93/500)、31.5%(63/200)、33.9%(339/1 000)和41.9%(419/1 000)]、高脂血症[分别为3.9%(39/1 000)、15.2%(19/125)、18.4%(23/125)和21.9%(219/1 000)]、高血压[分别为13.4%(67/500)、30.6%(153/500)、36.0%(9/25)、41.7%(417/1 000)]患病率均随时间有所上升(χ2=115.67、129.41、193.81,P均<0.01),而糖尿病患病率[分别为8.6%(43/500)、16.6%(83/500)、15.3%(153/1 000)、15.6%(39/250)]在2014年之后有所下降(χ2=29.99,P<0.01)。

|

图 1 不同年份RA患者CHD及其相关并发症患病率 Fig 1 Prevalence of CHD and related complications in RA patients in different years RA: Rheumatoid arthritis; CHD: Coronary heart disease; DM: Diabetes mellitus; HLP: Hyperlipidemia; HTN: Hypertension |

2.2 RA患者和OA患者CHD患病率及实验室指标差异

未进行倾向评分匹配前,与OA患者相比,RA患者CHD患病率较低[32.3%(1 751/5 426)vs 39.3%(583/1 483)],差异有统计学意义(P<0.01);RA患者炎症指标(ESR、CRP)、炎性因子(IL-2R、IL-6、TNF-α)、HDL-C、自身抗体(RF、ACCP)、IgA、IgG、IgM、D-二聚体、FiB水平和AKA阳性率均高于OA患者,而总胆固醇、三酰甘油、补体4、肌酸激酶、血糖、尿酸水平均低于OA患者,差异均有统计学意义(P均<0.01)。见表 1。

|

|

表 1 未进行倾向评分匹配前RA与OA患者CHD患病率及实验室指标比较 Tab 1 Comparison of CHD prevalence and laboratory indicators between RA and OA patients before propensity score matching |

以年龄和性别按1:1进行倾向评分匹配后,两组患者CHD患病率差异无统计学意义(P=0.74);RA患者ESR、CRP、IL-2R、IL-6、HDL-C、RF、ACCP、D-二聚体、FiB、CK-MB水平和AKA阳性率均高于OA患者,肌酸激酶、血糖水平均低于OA患者,差异均有统计学意义(P均<0.05)。见表 2。

|

|

表 2 倾向评分匹配后RA与OA患者CHD患病率及实验室指标比较 Tab 2 Comparison of CHD prevalence and laboratory indicators between RA and OA patients after propensity score matching |

2.3 合并CHD与未合并CHD的RA患者实验室指标差异

合并CHD的RA患者的ESR、CRP、LDL-C、总胆固醇、三酰甘油、IgG-RF、ACCP、FiB、血糖、尿酸水平和AKA阳性率均高于未合并CHD的RA患者,而HDL-C、IgG、IgM和25-(OH)D水平均低于未合并CHD的RA患者,差异均有统计学意义(P均<0.05)。见表 3。

|

|

表 3 合并CHD与未合并CHD的RA患者实验室指标比较 Tab 3 Comparison of laboratory indexes between RA patients with or without CHD |

2.4 RA患者合并CHD影响因素分析

调整年龄、性别、身高、体重、病程及并发症等混杂因素后,并将患者服用的药物进行分类(分为DMARD、糖皮质激素、NSAID),采用logistic回归分析RA患者合并CHD的影响因素,结果显示RA患者CHD患病率与总胆固醇、ACCP、IgG、25-(OH)D水平呈负相关,与IgG-RF、尿酸水平呈正相关(P均<0.05)。但根据服用剂量将药物作为等级变量纳入logistic回归模型并调整混杂因素后,RA患者CHD患病率与总胆固醇水平则不相关(P=0.057),其他指标相关性不变。见表 4。

|

|

表 4 RA患者合并CHD影响因素的logistic回归分析 Tab 4 Logistic regression analysis of influencing factors of CHD in RA patients |

3 讨论

RA患者CHD患病风险较高,但由于其CHD临床表现与单纯CHD患者有所不同,同时一些传统危险因素如糖尿病、高血压、高脂血症等在RA患者中通常长时间未被发现或未经治疗[9],导致RA患者CHD漏诊率相对较高,更容易发生心源性猝死[10]。

CHD患病率在男女之间存在差异。性激素假说认为,雌激素和雄激素对脂蛋白浓度的影响不同是导致男女CHD患病率差异的主要原因,如雄激素的前体脱氢异雄酮硫酸盐能够影响脂质代谢,与心血管疾病的发生密切相关[11]。同时糖尿病等传统危险因素对女性的影响远远大于男性[12],然而男性存在的CHD危险因素却远远多于女性[13]。本研究回顾性分析近10年临床数据发现,男女RA患者CHD患病率差异无统计学意义,可能由于RA患者病理、服药等因素对患者脂质代谢影响所致。

值得注意的是,2009-2019年RA患者CHD患病率及其相关并发症高脂血症、高血压的发生率均有所上升。这可能与近几年人群饮食习惯、生活方式、经济状况的改变及自然环境的变化等多种因素的共同作用相关[14]。外地来院就诊危重症RA患者的比例不断提高,也可能是本研究中并发症总体发生率不断上升的原因。与之相反,日本由于实施烟草和血压的控制政策,以及制定糖尿病、胆固醇水平、BMI相关策略,2012年调查显示普通人群CHD死亡率较1980年降低56%[15]。也有研究指出,CHD患病率在发展中国家不断增高,而在发达国家逐渐下降[16]。RA与OA患者之间CHD发生率是否不同存在争议,本研究在调整年龄、性别因素后,发现CHD患病率在RA患者与同时期OA患者之间差异并无统计学意义。

动脉壁细胞、心肌细胞、免疫细胞中均发现存在维生素D受体[17]。维生素D通过多种机制,如调节免疫系统、抑制内皮细胞功能障碍和血管平滑肌细胞的增殖与迁移,以及对高血压、血脂异常、代谢综合征等动脉粥样硬化相关疾病的全身性调节[18]等,发挥着动脉粥样硬化保护作用。另有研究指出,维生素D缺乏时心脏组织中组蛋白去乙酰化酶1蛋白表达减少,p65蛋白表达增加,促进炎症反应发生,最终诱导或加重CHD状态[19]。本研究结果同样显示25-(OH)D是RA患者并发CHD的保护因素。然而在RA患者中25-(OH)D缺乏很常见,因此,在临床治疗过程中应重视25-(OH)D的检测并及早采取干预措施,以避免RA患者由于25-(OH)D缺乏导致的CHD患病风险。

血清总胆固醇水平升高是CHD的重要危险因素。研究发现,在中国人群中总胆固醇每升高1 mmol/L女性的CHD死亡率增加27%、男性增加50%[20]。一项汇集7个国家数据的研究显示,在西方国家CHD死亡率随着总胆固醇水平增高呈上升趋势,而在日本则呈现相反的趋势,即CHD死亡率随着总胆固醇水平增高呈下降趋势[21]。另一项跨越半个世纪的研究得到了同样的结果[22]。本研究将患者服用的药物进行分类(分为DMARD、糖皮质激素、NSAID)后纳入logistic回归模型,并调整年龄、性别、病程等混杂因素的影响,结果显示RA患者CHD患病率与总胆固醇水平呈负相关(OR=0.527,95% CI 0.287~0.970,P=0.040);然而,当根据患者每类药物的服用剂量,将药物作为等级变量纳入logistic回归模型并调整混杂因素后,RA患者CHD患病率与总胆固醇水平并无相关关系(OR=0.546,95% CI 0.293~1.018,P=0.057)。因此,总胆固醇对RA患者并发CHD的影响仍需进一步探究。

RA的高度特异性标志物ACCP能够较好地预测病情和影像学改变,然而ACCP与心血管疾病的关系目前尚不明确。研究者更倾向于认为ACCP是心血管疾病的独立危险因素[23],也有研究指出循环ACCP水平与RA患者亚临床动脉粥样硬化相关[24]。动脉粥样硬化斑块内存在瓜氨酸化蛋白质表达,并且与4型肽基精氨酸脱亚胺酶共定位。ACCP可能通过靶向作用于动脉粥样硬化斑块内的瓜氨酸化表位,特别是瓜氨酸化纤维蛋白原促进局部免疫复合物和炎性斑块的发展,加速动脉粥样硬化的形成[25]。但是Aubry等[26]研究发现,与普通人群相比,RA患者动脉粥样硬化组织学改变并不显著。Majka等[27]的调查结果同样显示,在整个队列中ACCP与冠状动脉钙化并无相关性,性别分层分析发现男性冠状动脉钙化与ACCP水平呈负相关。本研究结果显示RA患者CHD患病率与ACCP水平呈负相关。一项基于高血压人群的研究显示,CHD患病率与血清IgG水平呈强负相关,并指出IgG水平可能受高血压影响[28],在本研究2018-2019年入组的RA患者中高血压患病率高达41.7%(417/1 000),并通过logistic回归模型得到相似的结论。

2010年CHD全球风险评估和应用指出,当临床医师知晓患者面临CHD高风险时,会更倾向于降低风险的治疗方案,如使用他汀类药物、阿司匹林、降血压药;当患者了解其自身CHD患病风险时,更会采取相关措施降低患病风险[29]。本研究通过探讨近10年RA患者CHD患病率及影响因素,提示临床医师在临床治疗中应重视RA患者的CHD患病风险,为RA患者提供更具针对性、更有效的治疗方案,最终降低CHD患病风险,提高患者生活质量。

| [1] |

GOODSON N. Coronary artery disease and rheumatoid arthritis[J]. Curr Opin Rheumatol, 2002, 14: 115-120. DOI:10.1097/00002281-200203000-00007 |

| [2] |

JOHN H, TOMS T E, KITAS G D. Rheumatoid arthritis:is it a coronary heart disease equivalent?[J]. Curr Opin Cardiol, 2011, 26: 327-333. DOI:10.1097/HCO.0b013e32834703b5 |

| [3] |

RAWLA P. Cardiac and vascular complications in rheumatoid arthritis[J]. Reumatologia, 2019, 57: 27-36. DOI:10.5114/reum.2019.83236 |

| [4] |

CAVALLI G, FAVALLI E G. Cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: impact of classic and disease-specific risk factors[J/OL]. Ann Transl Med, 2018, 6(Suppl 1): S82. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.10.72.

|

| [5] |

LYU Y, JIANG X, DAI W. The roles of a novel inflammatory neopterin in subjects with coronary atherosclerotic heart disease[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2015, 24: 169-172. DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2014.11.013 |

| [6] |

RAGGI P, GENEST J, GILES J T, RAYNER K J, DWIVEDI G, BEANLANDS R S, et al. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and therapeutic interventions[J]. Atherosclerosis, 2018, 276: 98-108. DOI:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.07.014 |

| [7] |

ALETAHA D, NEOGI T, SILMAN A J, FUNOVITS J, FELSON D T, BINGHAM C O 3, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria:an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative[J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2010, 62: 2569-2581. DOI:10.1002/art.27584 |

| [8] |

ALTMAN R, ASCH E, BLOCH D, BOLE G, BORENSTEIN D, BRANDT K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association[J]. Arthritis Rheum, 1986, 29: 1039-1049. DOI:10.1002/art.1780290816 |

| [9] |

KRÜGER K, NÜßLEIN H. Cardiovascular comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis[J]. Z Rheumatol, 2019, 78: 221-227. DOI:10.1007/s00393-018-0584-5 |

| [10] |

MARADIT-KREMERS H, CROWSON C S, NICOLA P J, BALLMAN K V, ROGER V L, JACOBSEN S J, et al. Increased unrecognized coronary heart disease and sudden deaths in rheumatoid arthritis:a population-based cohort study[J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2005, 52: 402-411. DOI:10.1002/art.20853 |

| [11] |

WU T T, ZHENG Y Y, YANG Y N, LI X M, MA Y T, XIE X. Age, sex, and cardiovascular risk attributable to lipoprotein cholesterol among Chinese individuals with coronary artery disease:a case-control study[J]. Metab Syndr Relat Disord, 2019, 17: 223-231. DOI:10.1089/met.2018.0067 |

| [12] |

LI J, LUO Y, GUO X, HUO X, LU J, REN Y, et al. Long exposure to type 2 diabetes and risk of non-fatal coronary heart disease in Chinese females and males:findings from a China national cross-sectional study[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2018, 137: 119-127. DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2017.10.025 |

| [13] |

IBRAHIM N K, MAHNASHI M, AL-DHAHERI A, AL-ZAHRANI B, AL-WADIE E, ALJABRI M, et al. Risk factors of coronary heart disease among medical students in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia[J/OL]. BMC Public Health, 2014, 14: 411. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-411.

|

| [14] |

PAPANDREOU C, TUOMILEHTO H. Coronary heart disease mortality in relation to dietary, lifestyle and biochemical risk factors in the countries of the seven countries study:a secondary dataset analysis[J]. J Hum Nutr Diet, 2014, 27: 168-175. DOI:10.1111/jhn.12187 |

| [15] |

OGATA S, NISHIMURA K, GUZMAN-CASTILLO M, SUMITA Y, NAKAI M, NAKAO Y M, et al. Explaining the decline in coronary heart disease mortality rates in Japan:contributions of changes in risk factors and evidence-based treatments between 1980 and 2012[J]. Int J Cardiol, 2019, 291: 183-188. DOI:10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.02.022 |

| [16] |

ZHU K F, WANG Y M, ZHU J Z, ZHOU Q Y, WANG N F. National prevalence of coronary heart disease and its relationship with human development index:a systematic review[J]. Eur J Prev Cardiol, 2016, 23: 530-543. DOI:10.1177/2047487315587402 |

| [17] |

NORMAN P E, POWELL J T. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease[J]. Circ Res, 2014, 114: 379-393. DOI:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301241 |

| [18] |

MENEZES A R, LAMB M C, LAVIE C J, DINICOLANTONIO J J. Vitamin D and atherosclerosis[J]. Curr Opin Cardiol, 2014, 29: 571-577. DOI:10.1097/HCO.0000000000000108 |

| [19] |

LIU Y, PENG W, LI Y, WANG B, YU J, XU Z. Vitamin D deficiency harms patients with coronary heart disease by enhancing inflammation[J]. Med Sci Monit, 2018, 24: 9376-9384. DOI:10.12659/MSM.911615 |

| [20] |

CRITCHLEY J, LIU J, ZHAO D, WEI W, CAPEWELL S. Explaining the increase in coronary heart disease mortality in Beijing between 1984 and 1999[J]. Circulation, 2004, 110: 1236-1244. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.0000140668.91896.AE |

| [21] |

SEKIKAWA A, MIYAMOTO Y, MIURA K, NISHIMURA K, WILLCOX B J, MASAKI K H, et al. Continuous decline in mortality from coronary heart disease in Japan despite a continuous and marked rise in total cholesterol:Japanese experience after the seven countries study[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2015, 44: 1614-1624. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyv143 |

| [22] |

HATA J, NINOMIYA T, HIRAKAWA Y, NAGATA M, MUKAI N, GOTOH S, et al. Secular trends in cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in Japanese:half-century data from the Hisayama study (1961-2009)[J]. Circulation, 2013, 128: 1198-1205. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002424 |

| [23] |

LÓPEZ-LONGO F J, OLIVER-MIÑARRO D, DE LA TORRE I, GONZÁLEZ-DÍAZ DE RÁBAGO E, SÁNCHEZ-RAMÓN S, RODRÍGUEZ-MAHOU M, et al. Association between anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies and ischemic heart disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis[J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2009, 61: 419-424. DOI:10.1002/art.24390 |

| [24] |

GERLI R, SHERER Y, BOCCI E B, VAUDO G, MOSCATELLI S, SHOENFELD Y. Precocious atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis:role of traditional and disease-related cardiovascular risk factors[J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2007, 1108: 372-381. DOI:10.1196/annals.1422.038 |

| [25] |

SOKOLOVE J, BRENNAN M J, SHARPE O, LAHEY L J, KAO A H, KRISHNAN E, et al. Brief report:citrullination within the atherosclerotic plaque:a potential target for the anti-citrullinated protein antibody response in rheumatoid arthritis[J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2013, 65: 1719-1724. |

| [26] |

AUBRY M C, MARADIT-KREMERS H, REINALDA M S, CROWSON C S, EDWARDS W D, GABRIEL S E. Differences in atherosclerotic coronary heart disease between subjects with and without rheumatoid arthritis[J]. J Rheumatol, 2007, 34: 937-942. |

| [27] |

MAJKA D S, VU T T, POPE R M, TEODORESCU M, KARLSON E W, LIU K, et al. Association of rheumatoid factors with subclinical and clinical atherosclerosis in African American women:the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis[J]. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2017, 69: 166-174. DOI:10.1002/acr.22930 |

| [28] |

KHAMIS R Y, HUGHES A D, CAGA-ANAN M, CHANG C L, BOYLE J J, KOJIMA C, et al. High serum immunoglobulin G and M levels predict freedom from adverse cardiovascular events in hypertension:a nested case-control substudy of the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial[J]. EBioMedicine, 2016, 9: 372-380. DOI:10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.06.012 |

| [29] |

VIERA A J, SHERIDAN S L. Global risk of coronary heart disease:assessment and application[J]. Am Fam Physician, 2010, 82: 265-274. |

2020, Vol. 41

2020, Vol. 41