2. 海军军医大学(第二军医大学)长海医院骨科, 上海 200433

2. Department of Orthopaedics, Changhai Hospital, Naval Medical University(Second Military Medical University), Shanghai 200433, China

牙周炎是由微生物引起、发病后会影响牙槽骨吸收和修复之间动态平衡的一种牙周支持组织的慢性炎症[1-2]。牙周炎发病后牙槽骨的修复弱于吸收,导致牙槽骨的高度降低[3-5]。牙周炎治疗的目的不仅要控制炎症、阻止病变进展,还要促进牙周组织的修复再生并形成新的组织[6-8]。因此,明确牙槽骨形成相关的基础细胞学和分子机制对于确定牙槽骨高度修复和促进牙周组织再生的特定靶标至关重要。

牙周韧带(periodontal ligament,PDL)是位于牙槽骨和牙骨质之间的纤维结缔组织带,可防止咀嚼时牙齿和牙槽骨受损[9],在牙周组织生理性形态与功能维持、病理性损坏和再生修复中发挥重要作用[10]。此外,PDL使牙齿能够在正畸治疗时通过牙周再生移动[11]。PDL由异质细胞群组成,包括成骨细胞、破骨细胞、成纤维细胞、成牙骨质细胞、间充质细胞、肥大细胞和吞噬细胞。人牙周膜干细胞(human periodontal ligament stem cell,hPDLSC)是存在于人牙周膜内间质来源的未分化细胞。Wang等[12]报道,无论是牙根还是牙槽骨表面的牙周膜干细胞(periodontal ligament stem cell,PDLSC)均具有形成牙骨质/牙周膜样结构的功能。牙周韧带成纤维细胞(periodontal ligament fibroblast,PDLF)具有产生富含胶原纤维的细胞外基质(extracellular matrix,ECM)[13]的能力,PDLSC与PDLF为相同来源的间质细胞,具有很高的相似性,可生成Ⅰ型胶原蛋白(collagen typeⅠ,ColⅠ)、Ⅲ型胶原蛋白(collagen type Ⅲ,ColⅢ)[14]并调节牙周组织中成骨细胞和破骨细胞的分化[15-16],推测PDLSC在牙周组织的完整性和修复性[17]及牙周疾病的预防[18]方面有一定作用。

降钙素(calcitonin,CT)由32个氨基酸构成,在1位和7位具有二硫键,并且末端羧基酰胺化,其生理功能多种多样,应用范围也越来越广。CT具有调节钙稳态的生理作用[19],还是骨代谢的重要调节剂[20],能有效地防止骨质流失,临床上用于治疗绝经后骨质疏松症[21-22]。Cheng等[23]报道CT不仅调节骨代谢,也通过上调胶原蛋白表达和抑制基质金属蛋白酶影响ECM的合成。然而,目前尚不清楚CT是否在牙周炎的PDLSC中参与调节ECM合成和成骨细胞分化。

本实验检测了慢性牙周炎(chronic periodontitis,CP)患者和健康受试者龈沟液(gingival crevicular fluid,GCF)中CT的表达水平,并分析了CT表达与患者临床参数之间的关系,还在体外用携带CT基因的重组腺病毒(Ad.CT)感染原代培养的hPDLSC,考察了CT对hPDLSC胶原合成和成骨作用的影响及潜在机制。

1 材料和方法 1.1 研究对象本研究方案经海军军医大学(第二军医大学)长海医院医学伦理委员会审批,患者均签署了知情同意书。50名成人受试者来自海军军医大学(第二军医大学)长海医院口腔科。CP根据美国牙周病学会的牙周病分类标准(1999年)[24]诊断。牙周临床参数包括牙周袋探诊深度(probing pocket depth,PD)、临床附着丧失(clinical attachment loss,CAL)和牙龈指数(gingival index,GI)。每个牙齿需检查6个部位:近颊、颊、离颊、近舌、舌和离舌。所有检测均由同一名检验员完成。通过GI、PD、CAL和骨丢失的影像学证据将所有受试者分为2组,每组25例。对照组受试者具有健康的牙周组织,GI<1、PD<3 mm、CAL=0 mm,未显示骨丢失的迹象;CP组患者有临床炎症迹象,GI>1、PD≥4 mm、CAL≥2 mm,有骨丢失的影像学证据。所有受试者均未患任何急性或慢性全身性疾病,且过去6个月未接受任何手术或非手术牙周治疗。排除在过去6个月内有吸烟、使用抗生素或免疫抑制药物史、怀孕或正在口服避孕药的患者。

1.2 位点选择与GCF样本采集CP组中选择探诊深度≥5 mm的上颌前部和有骨丢失影像学证据的部位,从每例患者的6个上颌位点收集GCF样本。对照组中,对没有炎症的多个部位(每名受试者10~12个)进行取样以确保收集足够量的GCF。将纸条轻轻地放置在龈沟的入口处以获得GCF样本,该区域使用棉卷隔离以避免唾液污染。小心地取出龈上菌斑并轻轻风干该部位。将条带以1~2 mm深度插入缝隙中30 s。使用Periotron 8000龈沟液测量仪(美国Oraflow公司)测定GCF体积。将来自每名受试者的条带置于含有300 μL pH为7.2的0.01 mol/L磷酸盐缓冲液(phosphate buffer saline,PBS)和蛋白酶抑制剂的标记管中。摇动20 min后除去条带,将洗脱液以5 800×g离心5 min除去菌斑和细胞成分。将收集的GCF立即转移并在-70℃储存直至测定时间。根据Tymkiw等[25]的研究,用酶联免疫吸附试验(enzyme linked immunosorbent assay,ELISA)测定GCF中CT的表达水平。

1.3 细胞培养与免疫化学测定hPDLSC细胞系来自ScienCell的健康捐献者并培养至第10代。将hPDLSC置于含有10%胎牛血清(fetal bovine serum,FBS)的DMEM培养液中,于37℃、5% CO2的加湿室中培养。每2 d更换培养液1次,在80%细胞融合度时传代。

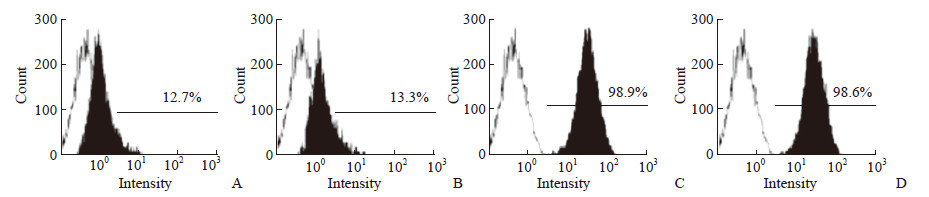

用流式细胞仪分析鉴定hPDLSC。牙周膜细胞(periodontal ligament cell,PDLC)表面抗原基质细胞抗原1(stromal cell antigen 1,STRO-1)和CD146检测阳性率较低,而在hPDLSC中阳性率较高,因此STRO-1和CD146高表达的细胞鉴定为hPDLSC。将hPDLSC继续传代培养至第5代进行细胞感染。

1.4 细胞感染使用AdEasy系统分别构建过表达人CT的重组腺病毒(Ad.CT)、过表达人头蛋白(noggin)的重组腺病毒(Ad.noggin)和特异性阻断转化生长因子β1(transforming growth factor β1,TGF-β1)小干扰RNA(small interfering RNA,siRNA)的重组腺病毒(Ad.TGF-β1 siRNA)。扩增人CT、头蛋白基因,合成TGF-β1 siRNA序列(5'-GGT GGA AAC CCA CAA CGA ATT-3'),分别克隆到pShuttleCMV质粒中。Ad.CT、Ad.noggin、Ad.TGF-β1 siRNA和空载腺病毒(Ad.Null)在人胚胎肾细胞中增殖,并使用美国BD公司Adeno-XTM病毒纯化试剂盒将其纯化。使用美国BD公司Adeno-XTM快速滴定试剂盒通过噬斑检测法测定腺病毒的分子活性。用Ad.CT或Ad.Null感染hPDLSC(感染复数为100),37℃下保持12 h。经绿色荧光蛋白(green fluorescent protein,GFP)检测,感染细胞百分比为87.3%。

1.5 实时定量PCR检测在重组腺病毒感染后72 h用TRIzol试剂提取hPDLSC总RNA并用POWERSCRIPT反转录试剂盒(美国BD公司)合成第一链cDNA。基因特异性引物如下:碱性磷酸酶(alkaline phosphatase,ALP)正义引物5'-ACT GGT ACT CAG ACA ACG AGA T-3',反义引物5'-ACG TCA ATG TCC CTG ATG TTA TG-3';骨形态发生蛋白(bone morphogenetic protein,BMP)2正义引物5'-GTA TCG CAG GCA CTC AGG TC-3',反义引物5'-CCT GAA GCT CTG CTG AGG TG-3';BMP4 正义引物5'-AAA GTC GCC GAG ATT CAG GG-3',反义引物5'-GAC GGC ACT CTT GCT AGG C-3';BMP7 正义引物5'-TCG GCA CCC ATG TTC ATG C-3',反义引物5'-GAG GAA ATG GCT ATC TTG CAG G-3';ColⅠ正义引物5'-CTC CAA CGA GAT CGA GAT CC-3',反义引物5'-GAA GCC GAA TTC CTG GTC TG-3';ColⅢ正义引物5'-CAG TTC TGG AGG ATG GTT GC-3',反义引物5'-TCT CAC AGC CTT GCG TGT TC-3';骨钙蛋白(osteocalcin,OCN)正义引物5'-GAA GTT TCG CAG ACC TGA CAT-3',反义引物5'-GTA TGC ACC ATT CAA CTC CTC G-3';TGF-β1正义引物5'-GGC CAG ATC CTG TCC AAG C-3',反义引物5'-GTG GGT TTC CAC CAT TAG CAC-3';18S rRNA正义引物5'-CGG ACA CGG ACA GGA TTG AC-3',反义引物5'-GCA TGC CAG AGT CTC GTT CG-3'。在LightCycler 480实时PCR系统(德国Roche公司)上使用即用型2×反应混合液(Fast Start Master SYBR Green Kit,德国Roche公司)进行实时定量PCR。用RealQuant软件(德国Roche公司)分析靶基因的mRNA表达,并将其标准化为18S rRNA的水平。

1.6 蛋白质印迹法检测在重组腺病毒感染后72 h用细胞裂解缓冲液提取hPDLSC总蛋白质,并通过BCA法测定总蛋白质浓度。取20 mg蛋白质进行12%十二烷基硫酸钠-聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳,并通过半干法将蛋白质转移到聚偏二氟乙烯(polyvinylidene fluoride,PVDF)膜上。将膜用5%脱脂乳在室温下封闭2 h,然后在4℃下用Tris盐酸盐缓冲液+Tween(TBST)稀释的小鼠抗人单克隆抗体(美国Santa Cruz公司)孵育过夜。次晨用TBST洗涤3次,每次5 min,并在室温下用辣根过氧化物酶标记的山羊抗小鼠二抗孵育2 h,用TBST洗涤3次后进行增强化学发光成像。使用LabWork 4.0程序分析蛋白质表达,并将其标准化为β-肌动蛋白(β-actin)的表达水平。

1.7 统计学处理用SPSS 22.0软件进行统计学分析。用Spearman相关分析评估CT表达水平与PD、CAL、GI、TGF-β1和BMP2/4/7的相关性。计量资料以x±s表示,两组间比较采用独立样本t检验。计数资料以例数和百分数表示,两组间比较采用χ2检验。检验水准(α)为0.05。

2 结果2.1两组患者基线资料比较见表 1,CP组患者GI、PD和CAL水平均高于对照组受试者(P均<0.01)。两组受试者年龄、性别差异均无统计学意义(P均>0.05),具有可比性。

|

|

表 1 两组患者基线资料比较 Tab 1 Comparison of general characteristics between two groups |

2.2 两组患者CT的表达水平比较及其与CP患者临床参数的关系

ELISA检测结果显示,CP组患者GCF中CT表达水平高于对照组[(32.62±1.46)ng/mL vs(17.70±0.76)ng/mL,P<0.01)];CP组患者CT的表达水平与GI、PD、CAL均呈负相关(P<0.01、P<0.05,表 2),而CT表达与年龄、性别等因素之间没有明显相关性(P均>0.05)。

|

|

表 2 CP患者的CT表达水平与临床参数的Spearman相关分析结果 Tab 2 Spearman correlation between CT expression and clinical parameters in CP patients |

2.3 CP患者BMP 2/4/7和TGF-β1的表达及其与CT表达的相关性

ELISA检测结果显示,CP组患者GCF中BMP2/4/7和TGF-β1的表达水平均高于对照组[BMP2:(138.67±4.04)ng/mL vs(103.96±2.78)ng/mL;BMP4:(155.53±3.55)ng/mL vs(133.15±2.92)ng/mL;BMP7:(106.59±2.85)ng/mL vs(90.22±1.56)ng/mL;TGF-β1:(105.92±3.40)ng/mL vs(89.85±2.42)ng/mL,P均<0.01],且CP患者上述指标的表达水平均与CT表达呈正相关(P<0.01、P<0.05,表 3)。

|

|

表 3 CP患者CT表达与TGF-β1和BMP2/4/7表达的Spearman相关分析结果 Tab 3 Spearman correlation of CT expression with TGF-β1 and BMP2/4/7 expression in CP patients |

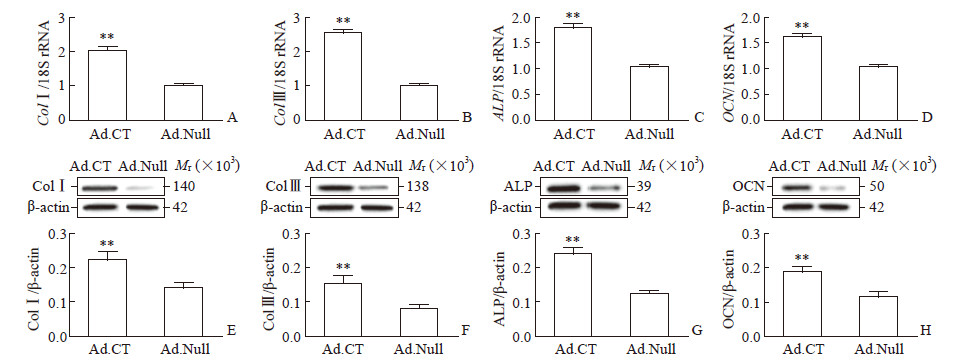

2.4 过表达CT增加ColⅠ/Ⅲ表达并诱导hPDLSC成骨细胞分化

经流式细胞仪分析鉴定,PDLC表面抗原STRO-1和CD146检测阳性率分别为12.7%及13.3%(图 1A、1B),而在hPDLSC中阳性率分别为98.9%及98.6%(图 1C、1D),表明在PDLC中成功分离出了纯度较高的hPDLSC。

|

图 1 流式细胞术检测PDLC和hPDLSC中STRO-1与CD146阳性细胞 Fig 1 STRO-1 and CD146 positive cells in PDLC and hPDLSC detected by flow cytometry A, B: PDLC; C, D: hPDLSC. A, C: STRO-1; B, D: CD146. PDLC: Periodontal ligament cell; hPDLSC: Human periodontal ligament stem cell; STRO-1: Stromal cell antigen 1 |

实时定量PCR和蛋白质印迹法分析结果(图 2)显示,与Ad.Null感染的hPDLSC相比,Ad.CT感染的hPDLSC中ColⅠ/Ⅲ、ALP、OCN的mRNA和蛋白质表达水平均上调,差异均有统计学意义(P均<0.01)。

|

图 2 过表达CT上调hPDLSC中ColⅠ/Ⅲ、ALP、OCN的表达 Fig 2 CT overexpression upregulating ColⅠ/Ⅲ, ALP and OCN expression in hPDLSC Relative mRNA expression of ColⅠ (A), Col Ⅲ (B), ALP (C) and OCN (D) and relative protein expression of ColⅠ (E), Col Ⅲ (F), ALP (G) and OCN (H) in hPDLSC infected with Ad.CT or Ad.Null were detected by quantitative real-time PCR and Western blotting, respectively. CT: Calcitonin; hPDLSC: Human periodontal ligament stem cell; Col: Collagen; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; OCN: Osteocalcin; Ad.CT: Recombinant adenovirus carrying CT gene; Ad.Null: Empty vector adenovirus. **P < 0.01 vs Ad.Null group. n=4, x±s |

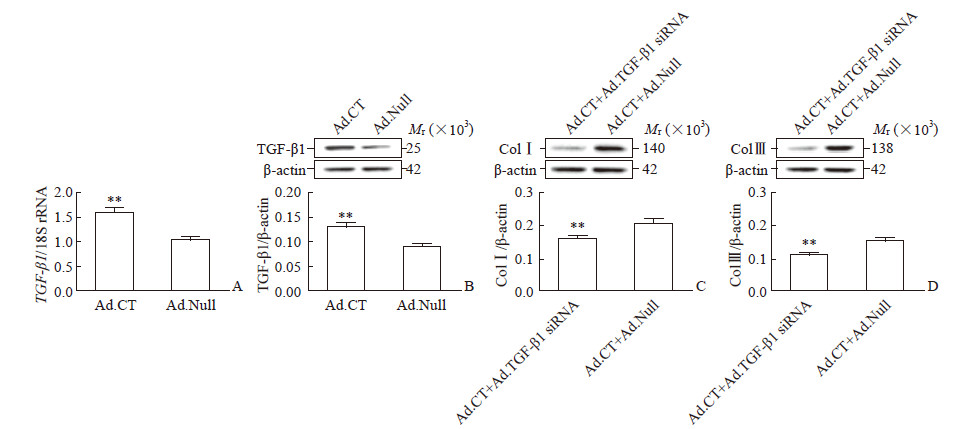

2.5 CT通过TGF-β1介导的通路上调hPDLSC中ColⅠ/Ⅲ的表达

与Ad.Null感染的hPDLSC相比,Ad.CT感染的hPDLSC中TGF-β1的mRNA和蛋白质表达均上调(P均<0.01,图 3A、3B);与Ad.CT和Ad.Null共同感染的hPDLSC相比,用Ad.CT和Ad.TGF-β1 siRNA共感染的细胞中ColⅠ/Ⅲ表达水平更低(ColⅠ:0.16±0.02 vs 0.22±0.03;ColⅢ:0.11±0.01 vs 0.15±0.02;P均<0.01;图 3C、3D)。

|

图 3 CT通过促进TGF-β1表达上调hPDLSC中ColⅠ/Ⅲ的表达 Fig 3 CT elevating ColⅠ/Ⅲ expression by increasing TGF-β1 expression in hPDLSC Relative mRNA (A) and protein (B) expression of TGF-β1 in hPDLSC infected with Ad.CT or Ad.Null, and relative protein expression of ColⅠ (C) and Col Ⅲ (D) in hPDLSC co-infected with Ad.CT+Ad.TGF-β1 siRNA or Ad.CT+Ad.Null were detected by quantitative real-time PCR and Western blotting, respectively. CT: Calcitonin; TGF-β1: Transforming growth factor β1; hPDLSC: Human periodontal ligament stem cell; Col: Collagen; Ad.CT: Recombinant adenovirus carrying CT gene; Ad.Null: Empty vector adenovirus; Ad.TGF-β1 siRNA: Recombinant adenovirus specifically blocking small interfering RNA of TGF-β1. **P < 0.01 vs Ad.Null group (A, B) or Ad.CT+Ad.Null group (C, D). n=4, x±s |

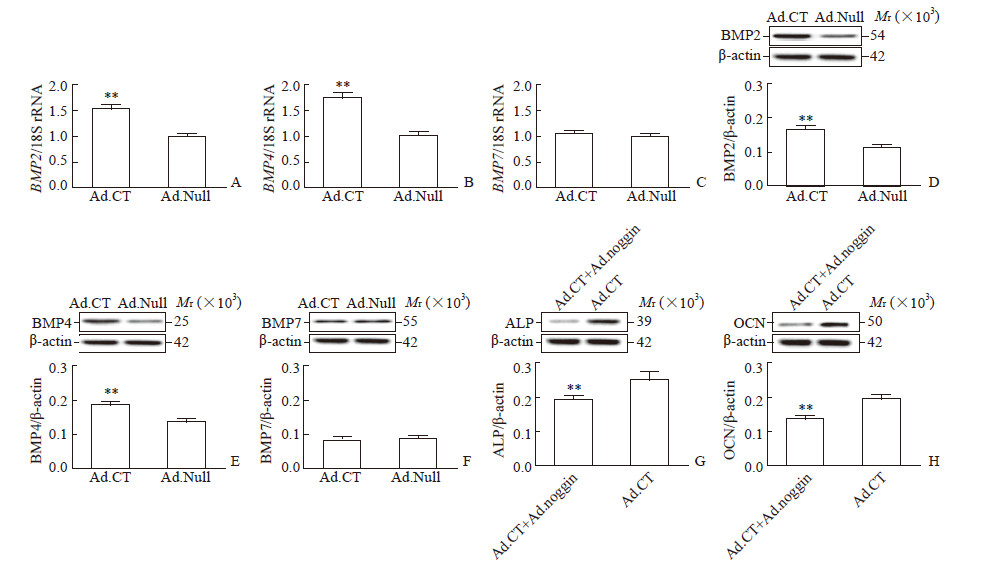

2.6 CT通过BMP2/4介导的通路诱导hPDLSC成骨细胞分化

与Ad.Null感染的hPDLSC相比,Ad.CT感染的hPDLSC中BMP2/4的mRNA和蛋白质表达水平均升高(P均<0.01,图 4A、4B、4D、4E),然而BMP7的mRNA和蛋白质表达在两组间差异均无统计学意义(图 4C、4F)。另外,与Ad.CT感染的hPDLSC相比,Ad.CT和Ad.noggin共处理的hPDLSC中ALP和OCN的蛋白质表达均降低(ALP:0.19±0.02 vs 0.25±0.03;OCN:0.13±0.01 vs 0.19±0.02;P均<0.01;图 4G、4H)。

|

图 4 CT通过BMP2/4介导的途径诱导hPDLSC成骨细胞分化 Fig 4 CT inducing hPDLSC osteoblastic differentiation through BMP2/4-meditated pathway Relative mRNA and protein expression of BMP-2 (A, D), BMP4 (B, E) and BMP7 (C, F) in hPDLSC infected with Ad.CT or Ad.Null, and relative protein expression of ALP (G) and OCN (H) in hPDLSC co-treated with Ad.CT+Ad.noggin or treated with Ad.CT alone were detected by quantitative real-time PCR and Western blotting, respectively. CT: Calcitonin; BMP: Bone morphogenetic protein; hPDLSC: Human periodontal ligament stem cell; Col: Collagen; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; OCN: Osteocalcin; Ad.CT: Recombinant adenovirus carrying CT gene; Ad.Null: Empty vector adenovirus. **P < 0.01 vs Ad.Null group (A-F) or Ad.CT group (G, H). n=4, x±s |

3 讨论

hPDLSC具有向牙周膜、牙骨质等多种牙周组织细胞分化的潜能,在牙周组织再生过程中发挥重要作用。研究显示,hPDLSC成骨分化受到牙周组织局部微环境中多种细胞因子的调控[26]。而hPDLSC与PDLF为相同来源的间质细胞,具有很大相似性。有研究报道,CT家族成员通过增强PDLF中胶原合成和成骨细胞分化,促进牙周炎发病后的损伤修复[27-28]。我们推测,CT也同样能增强hPDLSC中胶原合成和成骨分化。

本实验表明,CP患者组GCF中CT的表达高于对照组,同时CT的表达与CP的临床指标GI、PD、CAL均呈负相关,提示CT与CP发病有关并能促进其损伤修复。其中,hPDLSC分化是修复的一个关键过程[16]。牙周炎动物模型研究显示,牙槽骨修复时hPDLSC的增殖和基质蛋白的表达均增加(如ALP和OCN)[29],提示牙槽骨的修复可能是通过hPDLSC中的ECM合成和成骨细胞分化完成的[29-30]。本实验中,CT上调了成骨细胞标志物(BMP2/4、ALP、OCN)和ColⅠ/Ⅲ的表达,增强了胶原合成并促进了成骨细胞分化。我们认为CT可能通过增强hPDLSC中的ECM合成和成骨细胞分化来促进牙周炎发病后牙槽骨的损伤修复。

TGF-β1家族的成员如TGF-β1和BMP等都有调节hPDLSC中ECM合成和成骨细胞分化的功能[31]。Tian等[32]报道CT家族成员降钙素基因相关肽(calcitonin gene-related peptide,CGRP)可以调节人骨肉瘤细胞系MG-63中BMP2的表达和诱导成骨分化。同时,CT和CGRP识别相同的细胞受体[33],并通过与CGRP相同的途径调节hPDLSC中胶原合成和成骨细胞分化。故我们推测TGF-β1家族某些成员与CT调节ECM合成和成骨作用有关。

有学者发现用TGF-β1处理后人PDLF中基质蛋白如胶原蛋白表达增加[34],提示TGF-β1能增强PDLF的ECM合成。我们推测,与人PDLF来源相同的hPDLSC中的胶原蛋白经TGF-β1处理后表达也增加。本实验结果表明CT和TGF-β1在CP患者的GCF中表达均较高,且CT可促进TGF-β1表达,抑制TGF-β1可逆转CT对hPDLSC胶原合成的促进作用。因此,我们认为CT/TGF-β1通路可能参与了CP的发生、发展,CT通过自分泌或旁分泌作用上调内源性TGF-β1表达,促进hPDLSC的胶原合成。

目前已知多种BMP如BMP2、4、7与细胞成骨分化密切相关[35]。Hashimi[36]和Mi等[37]研究表明,上调BMP2/4可诱导人PDLF的钙化和成骨;还有研究报道BMP7的局部释放可以修复大鼠损伤修复模型中丢失的牙周支持结构[38]。我们推测,hPDLSC中BMP2/4通路也可调节成骨分化。本实验结果表明BMP2/4的表达与CP患者的CT表达有关,CT提高了BMP2/4的表达并诱导hPDLSC成骨分化,同时通过阻断BMP通路抑制CT诱导的hPDLSC成骨分化。另一方面,本实验中虽然BMP7表达在CP患者中升高,且与CT表达有关,但CT过表达并未明显增强hPDLSC中BMP7的表达,表明CT可能通过hPDLSC中的BMP2/4通路调节成骨分化,但没有激活BMP7通路。

临床研究结果显示,CT与牙周炎之间存在相关性而非因果关系[39]。结合本实验中CT可诱导hPDLSC中胶原蛋白合成和成骨分化的结果,我们认为CT可以促进CP发病后的组织修复,CT水平较高的CP患者表现出相对轻微的症状。虽然动物实验[40]和我们的体外细胞实验都表明CT过表达在牙周损伤修复过程中发挥作用,但仍需大量临床样本和动物模型进一步研究。

| [1] |

CHENG R, LIU W, ZHANG R, FENG Y, BHOWMICK N A, HU T. Porphyromonas gingivalis-derived lipopolysaccharide combines hypoxia to induce caspase-1 activation in periodontitis[J/OL]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2017, 7: 474. doi: 10.3389/fctmb.2017.00474.

|

| [2] |

KETHARANATHAN V, TORGERSEN G R, PETROVSKI B É, PREUS H R. Radiographic alveolar bone level and levels of serum 25-OH-vitamin D in ethnic Norwegian and Tamil periodontitis patients and their periodontally healthy controls[J/OL]. BMC Oral Health, 2019, 19: 83. doi: 10.1186/s12903-019-0769-6.

|

| [3] |

AVILA-ORTIZ G, NEIVA R, GALINDO-MORENO P, RUDEK I, BENAVIDES E, WANG H L. Analysis of the influence of residual alveolar bone height on sinus augmentation outcomes[J]. Clin Oral Implants Res, 2012, 23: 1082-1088. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02270.x |

| [4] |

TRIPUWABHRUT P, MUSTAFA K, BRUDVIK P, MUSTAFA M. Initial responses of osteoblasts derived from human alveolar bone to various compressive forces[J]. Eur J Oral Sci, 2012, 120: 311-318. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0722.2012.00980.x |

| [5] |

YODTHONG N, CHAROEMRATROTE C, LEETHANAKUL C. Factors related to alveolar bone thickness during upper incisor retraction[J]. Angle Orthod, 2013, 83: 394-401. DOI:10.2319/062912-534.1 |

| [6] |

CHEN F M, JIN Y. Periodontal tissue engineering and regeneration: current approaches and expanding opportunities[J]. Tissue Eng Part B Rev, 2010, 16: 219-255. DOI:10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0562 |

| [7] |

KAO D W, FIORELLINI J P. Regenerative periodontal therapy[J]. Front Oral Biol, 2012, 15: 149-159. |

| [8] |

RAMSEIER C A, ASPERINI G, BATIA S, GIANNOBILE W V. Advanced reconstructive technologies for periodontal tissue repair[J]. Periodontol 2000, 2012, 59: 185-202. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00432.x |

| [9] |

NAVEH G R, LEV-TOV CHATTAH N, ZASLANSKY P, SHAHAR R, WEINER S. Tooth-PDL-bone complex: response to compressive loads encountered during mastication—a review[J]. Arch Oral Biol, 2012, 57: 1575-1584. DOI:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.07.006 |

| [10] |

WYGANOWSKA-SWIATKOWSKA M, NOHAWICA M M. Effect of tobacco smoking on human gingival and periodontal fibroblasts. A systematic review of literature[J]. Przegl Lek, 2015, 72: 158-160. |

| [11] |

NODA K, NAKAMURA Y, KOGURE K, NOMURA Y. Morphological changes in the rat periodontal ligament and its vascularity after experimental tooth movement using superelastic forces[J]. Eur J Orthod, 2009, 31: 37-45. DOI:10.1093/ejo/cjn075 |

| [12] |

WANG L, SHEN H, ZHENG W, TANG L, YANG Z, GAO Y, et al. Characterization of stem cells from alveolar periodontal ligament[J]. Tissue Eng Part A, 2011, 17(7/8): 1015-1026. |

| [13] |

LALLIER T E, YUKNA R, MOSES R L. Extracellular matrix molecules improve periodontal ligament cell adhesion to anorganic bone matrix[J]. J Dent Res, 2001, 80: 1748-1752. DOI:10.1177/00220345010800081301 |

| [14] |

XU H, HAN X, MENG Y, GAO L, GUO Y, JING Y, et al. Favorable effect of myofibroblasts on collagen synthesis and osteocalcin production in the periodontal ligament[J]. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 2014, 145: 469-479. DOI:10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.12.019 |

| [15] |

JACOBS C, GRIMM S, ZIEBART T, WALTER C, WEHRBEIN H. Osteogenic differentiation of periodontal fibroblasts is dependent on the strength of mechanical strain[J]. Arch Oral Biol, 2013, 58: 896-904. DOI:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2013.01.009 |

| [16] |

KONSTANTONIS D, PAPADOPOULOU A, MAKOU M, ELIADES T, BASDRA E K, KLETSAS D. Senescent human periodontal ligament fibroblasts after replicative exhaustion or ionizing radiation have a decreased capacity towards osteoblastic differentiation[J]. Biogerontology, 2013, 14: 741-751. DOI:10.1007/s10522-013-9449-0 |

| [17] |

KONERMANN A, STABENOW D, KNOLLE P A, HELD S A, DESCHNER J, JÄGER A. Regulatory role of periodontal ligament fibroblasts for innate immune cell function and differentiation[J]. Innate Immun, 2012, 18: 745-752. DOI:10.1177/1753425912440598 |

| [18] |

EL-AWADY A R, LAPP C A, GAMAL A Y, SHARAWY M M, WENGER K H, CUTLER C W, et al. Human periodontal ligament fibroblast responses to compression in chronic periodontitis[J]. J Clin Periodontol, 2013, 40: 661-671. DOI:10.1111/jcpe.12100 |

| [19] |

GRECO K V, NALESSO G, KANEVA M K, SHERWOOD J, IQBAL A J, MORADI-BIDHENDI N, et al. Analyses on the mechanisms that underlie the chondroprotective properties of calcitonin[J]. Biochem Pharmacol, 2014, 91: 348-358. DOI:10.1016/j.bcp.2014.07.034 |

| [20] |

DAVEY R A, FINDLAY D M. Calcitonin: physiology or fantasy?[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2013, 28: 973-979. DOI:10.1002/jbmr.1869 |

| [21] |

KARACHALIOS T, LYRITIS G P, KALOUDIS J, ROIDIS N, KATSIRI M. The effects of calcitonin on acute bone loss after pertrochanteric fractures. A prospective, randomised trial[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2004, 86: 350-358. |

| [22] |

MITCHNER N A, HARRIS S T. Current and emerging therapies for osteoporosis[J]. J Fam Pract, 2009, 58(7 Suppl Osteoporosis): S45-S49. |

| [23] |

CHENG T, ZHANG L, FU X, WANG W, XU H, SONG H, et al. The potential protective effects of calcitonin involved in coordinating chondrocyte response, extracellular matrix, and subchondral trabecular bone in experimental osteoarthritis[J]. Connect Tissue Res, 2013, 54: 139-146. DOI:10.3109/03008207.2012.760549 |

| [24] |

1999 International International Workshop for a classification of periodontal diseases and conditions. Papers. Oak Brook, Illinois, October 30-November 2, 1999[J]. Ann Periodontol, 1999, 4: i, 1-112.

|

| [25] |

TYMKIW K D, THUNELL D H, JOHNSON G K, JOLY S, BURNELL K K, CAVANAUGH J E, et al. Influence of smoking on gingival crevicular fluid cytokines in severe chronic periodontitis[J]. J Clin Periodontol, 2011, 38: 219-228. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01684.x |

| [26] |

MAMALIS A, MARKOPOULOU C, LAGOU A, VROTSOS I. Oestrogen regulates proliferation, osteoblastic differentiation, collagen synthesis and periostin gene expression in human periodontal ligament cells through oestrogen receptor beta[J]. Arch Oral Biol, 2011, 56: 446-455. DOI:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.11.001 |

| [27] |

SUCHÁNEK J, BROWNE K Z, KLEPLOVÁ T S, MAZUROVÁ Y. Protocols for dental-related stem cells isolation, amplification and differentiation[M]//ZAVAN B, BRESSAN E. Dental stem cells: regenerative potential. Cham: Humana Press, 2016: 27-56.

|

| [28] |

MA W, ZHANG X, SHI S, ZHANG Y. Neuropeptides stimulate human osteoblast activity and promote gap junctional intercellular communication[J]. Neuropeptides, 2013, 47: 179-186. DOI:10.1016/j.npep.2012.12.002 |

| [29] |

SAITO M, TSUJI T. Extracellular matrix administration as a potential therapeutic strategy for periodontal ligament regeneration[J]. Expert Opin Biol Ther, 2012, 12: 299-309. DOI:10.1517/14712598.2012.655267 |

| [30] |

DANGARIA S J, ITO Y, LUAN X, DIEKWISCH T G. Successful periodontal ligament regeneration by periodontal progenitor preseeding on natural tooth root surfaces[J]. Stem Cells Dev, 2011, 20: 1659-1668. DOI:10.1089/scd.2010.0431 |

| [31] |

LI Y, TIAN A Y, OPHENE J, TIAN M Y, YAO Z, CHEN S, et al. TGF-β stimulates endochondral differentiation after denervation[J]. Int J Med Sci, 2017, 14: 382-389. DOI:10.7150/ijms.17364 |

| [32] |

TIAN G, ZHANG G, TAN Y H. Calcitonin gene-related peptide stimulates BMP-2 expression and the differentiation of human osteoblast-like cells in vitro[J]. Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2013, 34: 1467-1474. DOI:10.1038/aps.2013.41 |

| [33] |

NAOT D, CORNISH J. The role of peptides and receptors of the calcitonin family in the regulation of bone metabolism[J]. Bone, 2008, 43: 813-818. DOI:10.1016/j.bone.2008.07.003 |

| [34] |

LIU X, LONG X, LIU W, ZHAO Y, HAYASHI T, YAMATO M, et al. Type Ⅰ collagen induces mesenchymal cell differentiation into myofibroblasts through YAP-induced TGF-β1 activation[J]. Biochimie, 2018, 150: 110-130. DOI:10.1016/j.biochi.2018.05.005 |

| [35] |

CHEN G, DENG C, LI Y P. TGF-β and BMP signaling in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2012, 8: 272-288. DOI:10.7150/ijbs.2929 |

| [36] |

HASHIMI S M. Exogenous noggin binds the BMP-2 receptor and induces alkaline phosphatase activity in osteoblasts[J]. J Cell Biochem, 2019, 120: 13237-13242. DOI:10.1002/jcb.28597 |

| [37] |

MI H W, LEE M C, FU E, CHOW L P, LIN C P. Highly efficient multipotent differentiation of human periodontal ligament fibroblasts induced by combined BMP4 and hTERT gene transfer[J]. Gene Ther, 2011, 18: 452-461. DOI:10.1038/gt.2010.158 |

| [38] |

MOON J S, KIM M J, KO H M, KIM Y J, JUNG J Y, KIM J H, et al. The role of Hedgehog signaling in cementoblast differentiation[J]. Arch Oral Biol, 2018, 90: 100-107. DOI:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.03.006 |

| [39] |

ANKAM A, KODUGANTI R R. Calcitonin receptor gene polymorphisms at codon 447 in patients with osteoporosis and chronic periodontitis in South Indian population—an observational study[J]. J Indian Soc Periodontol, 2017, 21: 107-111. DOI:10.4103/jisp.jisp_128_16 |

| [40] |

WADA-MIHARA C, SETO H, OHBA H, TOKUNAGA K, KIDO J I, NAGATA T, et al. Local administration of calcitonin inhibits alveolar bone loss in an experimental periodontitis in rats[J]. Biomed Pharmacother, 2018, 97: 765-770. DOI:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.10.165 |

2019, Vol. 40

2019, Vol. 40