我国《原发性肝癌诊疗规范》(以下简称《规范》)[1]于2011年发布后,有效规范了我国原发性肝癌的临床诊疗,提高了我国肝癌的综合诊治水平。但2011年版《规范》并没有像美国肝病学会2010年指南[2]或欧洲肝病学会2012年指南[3]那样,将列举的循证医学证据加以分类、分级。另一方面,随着6年间肝癌相关临床、基础研究的进展,关于肝癌诊疗的新的研究证据不断扩充。为进一步提高肝癌(本文特指肝细胞肝癌;hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC)的总体疗效和改善患者的预后,国家卫生和计划生育委员会委托中华医学会,综合了121篇高质量文献,对2011年印发的《规范》进行了修订,发布了《原发性肝癌诊疗规范(2017年版)》[4]。2017年版《规范》提出了较多的更新,并首次引入牛津循证医学中心2011年版循证医学证据等级,对所阐述的临床结论进行推荐排序,做到与国际指南通用标准接轨。本文旨在对2017年版《规范》的更新要点予以解读。

1 HCC的筛查和诊断 1.1 HCC的筛查2017年版《规范》中HCC的筛查和2011年版基本一致,重点突出了乙型肝炎病毒(hepatitis B virus,HBV)感染、丙型肝炎病毒(hepatitis C virus,HCV)感染、酗酒、非酒精性脂肪性肝炎、黄曲霉素食品污染等因素导致的肝硬化为高危人群,推荐甲胎蛋白(α-fetoprotein, AFP)及B超检查为早期筛查手段,并至少每隔6个月随访1次[5]。

1.2 HCC的诊断在诊断板块中,2017年版《规范》省略了2011年版中关于“症状”和“体征”的描述,而是从影像学、血清学和病理学3方面阐述了HCC的诊断要点。

1.2.1 HCC的影像学诊断2017年版《规范》强调了HCC在MRI及CT增强扫描中特有的“快进快出”增强方式作为HCC影像学诊断的重要特点[6-7];同时指出钆塞酸二钠注射液(Gd-EOB-DTPA,商品名为普美显)作为对比剂在提高直径小于1 cm的HCC的检出率中的作用,从而优化了HCC诊断及鉴别诊断的准确性[8-12]。近年来随着研究的不断深入,2017年版《规范》对于正电子发射型计算机断层显像(PET-CT)的认可相较2011年版有了较多的更新:通过PET-CT能够全面评价淋巴结及远处器官转移,从而对HCC进行分期[13-14];可准确显示解剖结构发生变化后或解剖结构复杂部位的复发转移灶,并指导放疗生物靶区的勾画、指引穿刺部位[15-16];评价靶向药物疗效[17-18]以及肿瘤恶性程度和预后[19-21]。

1.2.2 HCC的血清学标志物2017年版《规范》仍旧将AFP作为最常用、最重要的HCC血清分子标志物,对于AFP阴性的患者,AFP异质体、α-L-岩藻糖苷酶、异常凝血酶原等有助于提高诊断率。

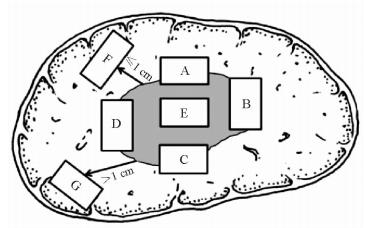

1.2.3 HCC的病理学诊断由于肝肿瘤的外周区域是肿瘤异质性的代表区域,也是微血管侵犯(microvascular invasion, MVI)和卫星结节形成的高发区域,这一区域的生物学特性直接影响了肿瘤的转移、复发和预后[22],因此基于上述对肝肿瘤异质性和微环境的新认知,2017年版《规范》推荐了“7点”基线取材法作为病理取材规范:在肿瘤的12点、3点、6点和9点位置上于肝癌与癌旁组织交界处按1:1取材;在肿瘤内部至少取材1块;对距肿瘤边缘≤1 cm(近癌旁)和>1 cm(远癌旁)范围内的肝组织分别取材1块(图 1)[23]。鉴于多结节性肝癌具有单中心和多中心两种起源方式,在不能除外由肝内转移引起的卫星结节的情况下,单个肿瘤最大直径≤3 cm的肝肿瘤应全部取材检查。实际取材的部位和数量还需根据肿瘤的直径和数量等情况考虑[24]。

|

图 1 肝脏肿瘤标本基线取材部位示意图[4, 23] Fig 1 Sketch of sampling position of liver tumor samples[4, 23] A, B, C, D indicate the 12, 3, 6 and 9 o’clock position of the junction of tumor and paracancerous tissues, respectively; E indicates the tumor section; F indicates the adjacent non-tumor tissues; G indicates the distant non-tumor tissues |

在镜下病理描述中,2017年版《规范》提出MVI的概念。MVI也被称为微血管癌栓,是指在显微镜下于内皮细胞衬覆的血管腔内见到癌细胞巢团。有研究认为,哪怕是直径小于3 cm的小肝癌中,MVI的出现仍然提示复发风险增加和远期生存率降低[25],故2017年版《规范》推荐将MVI作为常规病理检查指标[26-28]。2017年版《规范》根据MVI的数量及分布情况,提出了MVI病理分级方法:M0,未发现MVI;M1(低危组),≤5个MVI,且发生于近癌旁肝组织;M2(高危组),>5个MVI,或MVI发生于远癌旁肝组织。

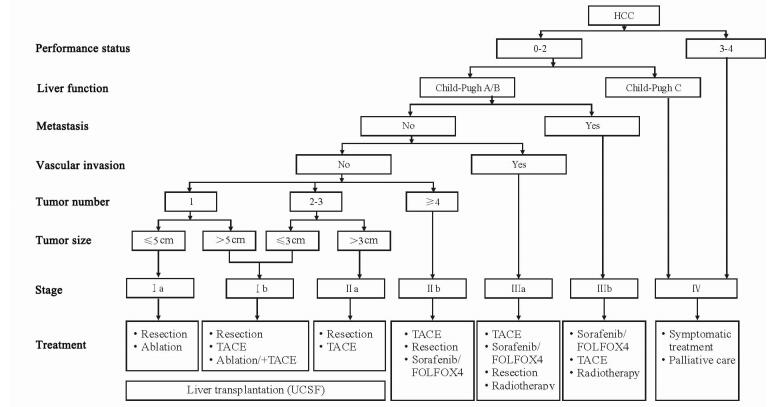

2 HCC的分期2011年版《规范》中推荐的TNM分期、巴塞罗那分期(Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer,BCLC)均为国外学术机构所提出的HCC常用分期系统,而2017年版《规范》根据我国国情和临床实践积累,提出了适合我国HCC患者的肝癌分期方案(图 2)。在肝功能和全身情况良好,不伴有肝外转移、血管侵犯的情况下,肿瘤单发且直径小于5 cm的为Ⅰa期;肿瘤单发且直径大于5 cm,以及肿瘤多发、数量不超过3个、最大直径不超过3 cm的为Ⅰb期;肿瘤多发、数量不超过3个、最大直径超过3 cm的为Ⅱa期;肿瘤数量超过3个的为Ⅱb期。有血管侵犯,但无肝外转移的为Ⅲa期;有肝外转移的为Ⅲb期。肝功能差、全身情况不理想的为Ⅳ期。可见,该分期综合了肿瘤大小、肿瘤数量、血管侵犯、肝外侵犯、肝功能和全身一般情况等各项指标,并相应给出了治疗意见。

|

图 2 肝癌临床分期及治疗路线图[4] Fig 2 Staging system and treatment roadmap of hepatocellular carcinoma[4] HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; TACE: Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization; UCSF: University of California, San Francisco |

3 HCC的治疗 3.1 HCC的外科治疗 3.1.1 肝癌切除适应证

根据上述分期系统,2017年版《规范》提出Ⅰa、Ⅰb和Ⅱa期是手术切除的首选适应证。而对于部分可能通过手术获益的Ⅱb、Ⅲa期的患者,在谨慎的术前评估下,也可尝试手术切除。同时,2017年版《规范》认为位于Couinaud Ⅱ、Ⅲ、Ⅳb、Ⅴ、Ⅵ段且大小不影响第一和第二肝门解剖、直径<10 cm的肝肿瘤是行腹腔镜肝切除的指征,而对于腔镜经验丰富的医师,半肝、三叶以及Ⅰ、Ⅶ、Ⅷ段的肝切除也并非禁忌。

3.1.2 提高肝癌可切除性对于切除范围较大导致余肝体积过少或顾忌余肝功能的HCC患者,2011年版《规范》推荐采用术前经导管动脉化学栓塞(transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, TACE)术缩小肿瘤及门静脉栓塞(PVE)术使健侧肝脏代偿增大2个策略,而2017年版《规范》在2011年版基础上引入了近年来研究的热点技术:联合肝脏分隔和门静脉结扎的二步肝切除术(associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy, ALPPS)。该术式通过Ⅰ期的肝脏分隔或离断和患侧门静脉分支结扎后,使健侧剩余肝脏体积(future liver remnant, FLR)一般在1~2周后增生30%~70%以上,FLR占标准肝脏体积至少30%以上,可接受安全的Ⅱ期患侧肝脏切除[29]。

3.1.3 肝移植治疗在肝移植适应证上,2017年版《规范》沿用2011年版推荐的国际上较为通用的米兰标准和加州大学旧金山分校(UCSF)等标准,并结合国内实际情况推荐UCSF标准。而对于国内陆续提出的杭州标准、复旦标准、华西标准、三亚共识等[30-32],2017年版《规范》认为仍需进一步高级别循证医学证据验证。对于肝移植术后患者,新的研究认为早期减少钙调磷酸酶抑制剂的用量可能降低复发率[33],而应用哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白(mammalian target of rapamycin, mTOR)抑制剂可能会提高移植术后生存率[34-35]。

3.2 HCC的局部治疗 3.2.1 局部治疗的消融手段2017年版《规范》与2011年版内容基本一致,推荐射频消融(radiofrequency ablation, RFA)、微波消融(microwave ablation, MWA)及无水乙醇注射治疗(percutaneous ethanol injection,PEI)等我国较为常用的局部消融方式。

3.2.2 局部治疗的适应证2011年版《规范》认为局部治疗适用于单个肿瘤直径≤5 cm,或肿瘤结节不超过3个、最大肿瘤直径≤3 cm,无血管、胆管和邻近器官侵犯以及远处转移的患者。2017年版《规范》在此基础上补充了对于3~7 cm的单发肿瘤或多发肿瘤,与单纯局部治疗相比,局部治疗联合TACE可改善患者生存[36-37]。此外,2011年版《规范》中对于直径≤5 cm的肝癌应首先局部治疗还是手术切除尚存争议,而2017年版《规范》总结新发表的前瞻性随机对照研究和系统回顾性分析显示,手术切除宜作为首选[38-41]。

3.3 HCC的TACE治疗 3.3.1 TACE治疗的基本原则2017年版《规范》在TACE治疗的原则上,强调超选择插管至肿瘤的供养血管内治疗;如经过4~5次TACE治疗后,肿瘤仍继续进展,应考虑换用或联合其他治疗方法,如外科手术、局部消融、系统治疗以及放射治疗等。

3.3.2 TACE的适应证结合新的肝癌分期,2017年版《规范》提出Ⅱb期、Ⅲa期及Ⅲb期患者为TACE治疗的合适人群,由于其他原因无法接受或不愿意接受手术的Ⅰb期和Ⅱa期患者也可接受TACE治疗。

3.3.3 TACE的操作程序2017年版《规范》强调在碘油乳剂栓塞后,应加用颗粒性栓塞剂(如标准化明胶海绵颗粒、微球、聚乙烯醇颗粒等),以达到更好的栓塞效果,尽可能做到肿瘤去血管化。

3.3.4 TACE术后疗效评估鉴于TACE治疗很少能改变肿瘤大小,2017年版《规范》推荐实体瘤疗效评价标准修订版(modifed Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumor,mRECIST)评估肝癌介入术后疗效。与RECIST相比,该标准的重点在于以增强MRI动脉期肿瘤血供活性范围而不是以肿瘤直径作为评估疗效的标准,更客观、准确地评估介入术后肝癌治疗效果[42]。

3.3.5 TACE联合治疗2017年版《规范》重视TACE结合其他局部或全身治疗,包括TACE联合局部消融治疗、放疗、Ⅱ期手术切除及全身分子靶向治疗、化疗等[43]。

3.4 HCC的放射治疗2017年版《规范》中,将放射治疗分为外放射及内放射两部分予以阐述。

3.4.1 HCC的外放射治疗2017年版《规范》推荐外放射治疗的适应证为伴有门静脉/下腔静脉癌栓或肝外转移的Ⅲa期患者。

3.4.2 HCC的内放射治疗90Y微球疗法[44]、131Ⅰ单克隆抗体[45]、放射性碘化油[46]、125Ⅰ粒子等放射性粒子植入相应肿瘤或受侵犯管腔内,可分别治疗肝内病灶、门静脉癌栓、下腔静脉癌栓和胆管内癌或癌栓。

3.5 HCC的全身治疗 3.5.1 靶向药物索拉非尼仍是目前唯一经过多中心Ⅲ期临床验证,可以使晚期肝癌患者得到生存获益的分子靶向药物[47]。

3.5.2 化疗药物根据EACH研究后期随访数据,含奥沙利铂的FOLFOX4方案在整体反应率、疾病控制率、无进展生存期、总生存期方面均优于传统化疗药物多柔比星[48],可应用于不适合手术切除或局部治疗的晚期肝癌患者。

3.5.3 抗病毒药物对于乙型肝炎相关性肝癌患者,恩替卡韦、替诺福韦酯等强效、低耐药率的抗病毒药物可预防TACE治疗等引起的病毒再激活,同时还可以降低术后复发率[49-50]。

4 小结综上所述,2017年版《规范》对2011年版《规范》进行了较多补充,主要体现在以下几点:(1) 对所阐述的临床问题提出建议的同时,添加了相应的循证医学等级,让读者有更为清晰的理解;(2) 规范了肝癌病理取材和报告,强调了MVI的重要性,以便更好地指导临床诊疗、判断预后;(3) 结合相关临床研究进展,提出了适合我国国情的肝癌分期系统和治疗路径,基本做到与欧美指南接轨,在治疗上更强调局部联合全身治疗;(4) 在TACE、靶向药物的疗效评判上,应用更适合肝癌的mRECIST标准。我们有理由相信,2017年版《规范》能更好地指导我国当前的肝癌临床工作。

| [1] | 中华人民共和国卫生部. 原发性肝癌诊疗规范[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2011, 27: 1141–1159. |

| [2] | BRUIX J, SHERMAN M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma:an update[J]. Hepatology, 2011, 53: 1020–1022. DOI: 10.1002/hep.24199 |

| [3] | European Association for the Study of the Liver; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines:management of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Hepatol, 2012, 56: 908–943. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001 |

| [4] | 中华人民共和国卫生和计划生育委员会医政医管局. 原发性肝癌诊疗规范(2017年版)[J]. 中华消化外科杂志, 2017, 16: 705–720. |

| [5] | ZHANG B H, YANG B H, TANG Z Y. Randomized controlled trial of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2004, 130: 417–422. |

| [6] | CHEN B B, MURAKAMI T, SHIH T T, SAKAMOTO M, MATSUI O, CHOI B I, et al. Novel imaging diagnosis for hepatocellular carcinoma:consensus from the 5th Asia-Pacific primary liver cancer expert meeting (APPLE 2014)[J]. Liver Cancer, 2015, 4: 215–227. DOI: 10.1159/000367742 |

| [7] | MERKLE E M, ZECH C J, BARTOLOZZI C, BASHIR M R, BA-SSALAMAH A, HUPPERTZ A, et al. Consensus report from the 7th International Forum for Liver Magnetic Resonance Imaging[J]. Eur Radiol, 2016, 26: 674–682. DOI: 10.1007/s00330-015-3873-2 |

| [8] | ZENG M S, YE H Y, GUO L, PENG W J, LU J P, TENG G J, et al. Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for focal liver lesions in Chinese patients:a multicenter, open-label, phaseⅢ study[J]. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int, 2013, 12: 607–616. DOI: 10.1016/S1499-3872(13)60096-X |

| [9] | LEE Y J, LEE J M, LEE J S, LEE H Y, PARK B H, KIM Y H, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma:diagnostic performance of multidetector CT and MR imaging-a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Radiology, 2015, 275: 97–109. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.14140690 |

| [10] | ICHIKAWA T, SAITO K, YOSHIOKA N, TANIMOTO A, GOKAN T, TAKEHARA Y, et al. Detection and characterization of focal liver lesions:a Japanese phase Ⅲ, multicenter comparison between gadoxetic acid disodium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and contrast-enhanced computed tomography predominantly in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic liver disease[J]. Invest Radiol, 2010, 45: 133–141. DOI: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181caea5b |

| [11] | YOO S H, CHOI J Y, JANG J W, BAE S H, YOON S K, KIM D G, et al. Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI is better than MDCT in decision making of curative treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2013, 20: 2893–900. DOI: 10.1245/s10434-013-3001-y |

| [12] | CHEN C Z, RAO S X, DING Y, ZHANG S J, LI F, GAO Q, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma 20 mm or smaller in cirrhosis patients:early magnetic resonance enhancement by gadoxetic acid compared with gadopentetate dimeglumine[J]. Hepatol Int, 2014, 8: 104–111. DOI: 10.1007/s12072-013-9467-7 |

| [13] | PARK J W, KIM J H, KIM S K, KANG K W, PARK K W, CHOI J I, et al. A prospective evaluation of 18F-FDG and 11C-acetate PET/CT for detection of primary and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Nucl Med, 2008, 49: 1912–1921. DOI: 10.2967/jnumed.108.055087 |

| [14] | LIN C Y, CHEN J H, LIANG J A, LIN C C, JENG L B, KAO C H. 18F-FDG PET or PET/CT for detecting extrahepatic metastases or recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Eur J Radiol, 2012, 81: 2417–2422. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.08.004 |

| [15] | OELLAARD R, DELGADO-BOLTON R, OYEN W J, GIAMMARILE F, TATSCH K, ESCHNER W, et al. European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). FDG PET/CT:EANM procedure guidelines for tumour imaging:version 2.0[J]. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2015, 42: 328–354. DOI: 10.1007/s00259-014-2961-x |

| [16] | BOELLAARD R, O'DOHERTY M J, WEBER W A, MOTTAGHY F M, LONSDALE M N, STROOBANTS S G, et al. FDG PET and PET/CT:EANM procedure guidelines for tumour PET imaging:version 1.0[J]. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2010, 37: 181–200. DOI: 10.1007/s00259-009-1297-4 |

| [17] | WAHL R L, JACENE H, KASAMON Y, LODGE M A. From RECIST to PERCIST:evolving considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors[J]. J Nucl Med, 2009, 50(Suppl 1): 122S–150S. |

| [18] | CHALIAN H, TÖRE H G, HOROWITZ J M, SALEM R, MILLER F H, YAGHMAI V. Radiologic assessment of response to therapy:comparison of RECIST Versions 1.1 and 1.0[J]. Radiographics, 2011, 31: 2093–2105. DOI: 10.1148/rg.317115050 |

| [19] | FERDA J, FERDOVÁ E, BAXA J, KREUZBERG B, DAUM O, T Ř EŠKA V, et al. The role of 18F-FDG accumulation and arterial enhancement as biomarkers in the assessment of typing, grading and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma using 18F-FDG-PET/CT with integrated dual-phase CT angiography[J]. Anticancer Res, 2015, 35: 2241–2246. |

| [20] | LEE J W, OH J K, CHUNG Y A, NA S J, HYUN S H, HONG I K, et al. Prognostic significance of 18F-FDG uptake in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization or concurrent chemoradiotherapy:a multicenter retrospective cohort study[J]. J Nucl Med, 2016, 57: 509–516. DOI: 10.2967/jnumed.115.167338 |

| [21] | HYUN S H, EO J S, LEE J W, CHOI J Y, LEE K H, NA S J, et al. Prognostic value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages 0 and A hepatocellular carcinomas:a multicenter retrospective cohort study[J]. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2016, 43: 1638–1645. DOI: 10.1007/s00259-016-3348-y |

| [22] | LU X Y, XI T, LAU W Y, DONG H, ZHU Z, SHEN F, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma expressing cholangiocyte phenotype is a novel subtype with highly aggressive behavior[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2011, 18: 2210–2217. DOI: 10.1245/s10434-011-1585-7 |

| [23] | 中国抗癌协会肝癌专业委员会, 中华医学会肝病学分会肝癌学组, 中国抗癌协会病理专业委员会, 中华医学会病理学分会消化病学组, 中华医学会外科学分会肝脏外科学组, 中国抗癌协会临床肿瘤学协作专业委员会, 等. 原发性肝癌规范化病理诊断指南(2015版)[J]. 临床与实验病理学杂志, 2015, 31: 241–246. |

| [24] | NARA S, SHIMADA K, SAKAMOTO Y, ESAKI M, KISHI Y, KOSUGE T, et al. Prognostic impact of marginal resection for patients with solitary hepatocellular carcinoma:evidence from 570 hepatectomies[J]. Surgery, 2012, 151: 526–536. DOI: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.12.002 |

| [25] | DU M, CHEN L, ZHAO J, TIAN F, ZENG H, TAN Y, et al. Microvascular invasion (MVI) is a poorer prognostic predictor for small hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. BMC Cancer, 2014, 14: 38. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-38 |

| [26] | EGUCHI S, TAKATSUKI M, HIDAKA M, SOYAMA A, TOMONAGA T, MURAOKA I, et al. Predictor for histological microvascular invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma:a lesson from 229 consecutive cases of curative liver resection[J]. World J Surg, 2010, 34: 1034–1038. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-010-0424-5 |

| [27] | FUJITA N, AISHIMA S, IGUCHI T, MANO Y, TAKETOMI A, SHIRABE K, et al. Histologic classification of microscopic portal venous invasion to predict prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hum Pathol, 2011, 42: 1531–1538. DOI: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.12.016 |

| [28] | IGUCHI T, SHIRABE K, AISHIMA S, WANG H, FUJITA N, NINOMIYA M, et al. New pathologic stratification of microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma:predicting prognosis after living-donor liver transplantation[J]. Transplantation, 2015, 99: 1236–1242. DOI: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000489 |

| [29] | D'HAESE J G, NEUMANN J, WENIGER M, PRATSCHKE S, BJÖRNSSON B, ARDILES V, et al. Should ALPPS be used for liver resection in intermediate-stage HCC?[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2016, 23: 1335–1343. DOI: 10.1245/s10434-015-5007-0 |

| [30] | ZHENG S S, XU X, WU J, CHEN J, WANG W L, ZHANG M, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma:Hangzhou experiences[J]. Transplantation, 2008, 85: 1726–1732. DOI: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816b67e4 |

| [31] | FAN J, YANG G S, FU Z R, PENG Z H, XIA Q, PENG C H, et al. Liver transplantation outcomes in 1, 078 hepatocellular carcinoma patients:a multi-center experience in Shanghai, China[J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2009, 135: 1403–1412. DOI: 10.1007/s00432-009-0584-6 |

| [32] | LI J, YAN L N, YANG J, CHEN Z Y, LI B, ZENG Y, et al. Indicators of prognosis after liver transplantation in Chinese hepatocellular carcinoma patients[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2009, 15: 4170–4176. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.15.4170 |

| [33] | RODRÍGUEZ-PERÁLVAREZ M, TSOCHATZIS E, NAVEAS M C, PIERI G, GARCÍA-CAPARRÁS C, O'BEIRNE J, et al. Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors early after liver transplantation prevents recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Hepatol, 2013, 59: 1193–1199. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.07.012 |

| [34] | LIANG W, WANG D, LING X, KAO A A, KONG Y, SHANG Y, et al. Sirolimus-based immunosuppression in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma:a meta-analysis[J]. Liver Transpl, 2012, 18: 62–69. DOI: 10.1002/lt.v18.1 |

| [35] | ZHOU J, WANG Z, WU Z Q, QIU S J, YU Y, HUANG X W, et al. Sirolimus-based immunosuppression therapy in liver transplantation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma exceeding the Milan criteria[J]. Transplant Proc, 2008, 40: 3548–3553. DOI: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.03.165 |

| [36] | PENG Z W, ZHANG Y J, CHEN M S, XU L, LIANG H H, LIN X J, et al. Radiofrequency ablation with or without transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma:a prospective randomized trial[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2013, 31: 426–432. |

| [37] | MORIMOTO M, NUMATA K, KONDOU M, NOZAKI A, MORITA S, TANAKA K. Midterm outcomes in patients with intermediate-sized hepatocellular carcinoma:a randomized controlled trial for determining the efficacy of radiofrequency ablation combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization[J]. Cancer, 2010, 116: 5452–5460. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.25314 |

| [38] | LIU P H, HSU C Y, HSIA C Y, LEE Y H, HUANG Y H, CHIOU Y Y, et al. Surgical resection versus radiofrequency ablation for single hepatocellular carcinoma ≤ 2 cm in a propensity score model[J]. Ann Surg, 2016, 263: 538–545. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001178 |

| [39] | FENG K, YAN J, LI X, XIA F, MA K, WANG S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection in the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Hepatol, 2012, 57: 794–802. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.05.007 |

| [40] | XU Q, KOBAYASHI S, YE X, MENG X. Comparison of hepatic resection and radiofrequency ablation for small hepatocellular carcinoma:a meta-analysis of 16, 103 patients[J]. Sci Rep, 2014, 4: 7252. DOI: 10.1038/srep07252 |

| [41] | HASEGAWA K, AOKI T, ISHIZAWA T, KANEKO J, SAKAMOTO Y, SUGAWARA Y, et al. Comparison of the therapeutic outcomes between surgical resection and percutaneous ablation for small hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2014, 21(Suppl 3): S348–S355. |

| [42] | LENCIONI R, LLOVET J M. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Semin Liver Dis, 2010, 30: 52–60. DOI: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132 |

| [43] | YANG M, FANG Z, YAN Z, LUO J, LIU L, ZHANG W, et al. Transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) combined with endovascular implantation of an iodine-125 seed strand for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumour thrombosis versus TACE alone:a two-arm, randomised clinical trial[J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2014, 140: 211–219. DOI: 10.1007/s00432-013-1568-0 |

| [44] | LAU W Y, TEOH Y L, WIN K M, LEE R C, DE VILLA V H, KIM Y H, et al. Current role of selective internal radiation with yttrium-90 in liver tumors[J]. Future Oncol, 2016, 12: 1193–1204. DOI: 10.2217/fon-2016-0035 |

| [45] | XU J, SHEN Z Y, CHEN X G, ZHANG Q, BIAN H J, ZHU P, et al. A randomized controlled trial of Licartin for preventing hepatoma recurrence after liver transplantation[J]. Hepatology, 2007, 45: 269–276. DOI: 10.1002/hep.v45:2 |

| [46] | RAOUL J L, GUYADER D, BRETAGNE J F, DUVAUFERRIER R, BOURGUET P, BEKHECHI D, et al. Randomized controlled trial for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis:intra-arterial iodine-131-iodized oil versus medical support[J]. J Nucl Med, 1994, 35: 1782–1787. |

| [47] | LLOVET J M, RICCI S, MAZZAFERRO V, HILGARD P, GANE E, BLANC J F, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. N Engl J Med, 2008, 359: 378–390. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857 |

| [48] | QIN S, BAI Y, LIM H Y, THONGPRASERT S, CHAO Y, FAN J, et al. Randomized, multicenter, open-label study of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin versus doxorubicin as palliative chemotherapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma from Asia[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2013, 31: 3501–3508. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.5643 |

| [49] | YIN J, LI N, HAN Y, XUE J, DENG Y, SHI J, et al. Effect of antiviral treatment with nucleotide/nucleoside analogs on postoperative prognosis of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma:a two-stage longitudinal clinical study[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2013, 31: 3647–3655. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5896 |

| [50] | HUANG G, LAU W Y, WANG Z G, PAN Z Y, YUAN S X, SHEN F, et al. Antiviral therapy improves postoperative survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma:a randomized controlled trial[J]. Ann Surg, 2015, 261: 56–66. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000858 |

2017, Vol. 38

2017, Vol. 38