细胞衰老是指增殖细胞脱离细胞周期呈永久性生长停滞的状态,可由DNA损伤、氧化应激、电离辐射、抗肿瘤药物等多种因素诱发[1]。β半乳糖苷酶(β-galactosidase, β-gal)活性升高是细胞衰老的特异性指标。衰老细胞新陈代谢非常活跃,其显著的特点之一是能分泌大量生物活性物质,如白细胞介素(interleukin, IL)-6、IL-8、IL-1α/β、基质金属蛋白酶(matrix metalloproteinaese,MMP)以及生长因子等,称为衰老细胞相关分泌表型(senescence-associated secretory phenotype,SASP)因子[2-4]。衰老细胞通过旁分泌SASP因子改变细胞微环境,从而影响肿瘤的发生和发展[5-7]。化学治疗是胃癌重要的治疗手段,可诱导细胞衰老[8],但有关衰老细胞SASP现象对胃癌细胞的影响目前尚未见报道。本研究通过建立胃癌细胞衰老模型制备胃癌衰老细胞相关分泌表型条件培养基(senescence-associated secretory phenotype-conditioned medium,SASP-CM),并使用SASP-CM培养人胃癌细胞系BGC823细胞,旨在探讨SASP-CM对胃癌细胞增殖的影响,以期为临床上化学治疗诱导衰老细胞的清除提供依据。

1 材料和方法 1.1 实验试剂与细胞人胃癌细胞系BGC823由中国生物化学和细胞生物学研究所提供,用于构建衰老细胞模型和细胞增殖实验。紫杉醇(paclitaxel,PTX,纯度99.74%)购自美国APExBIO公司(批号A4393),衰老检测试剂盒购自上海碧云天生物技术有限公司,RPMI 1640培养液、胎牛血清(fetal bovine serum,FBS)购自美国Gibco公司,酶联免疫吸附实验(enzyme linked immunosorbent assay, ELISA)试剂盒购自上海酶联生物科技有限公司,Annexin Ⅴ-增强型绿色荧光蛋白(enhanced green fluorescent protein,EGFP)和碘化丙啶(propidium iodide,PI)购自江苏凯基生物技术股份有限公司,细胞增殖与活性检测试剂盒购自和元生物技术(上海)科技有限公司。

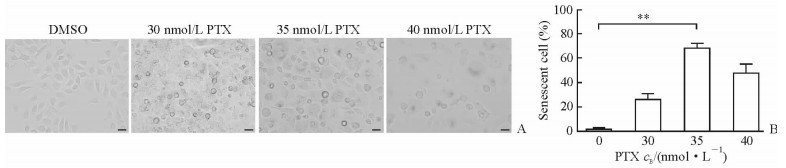

1.2 细胞衰老模型的构建于6孔板中以2×105/孔的密度接种BGC823细胞,待细胞融合达80%后换液,分别用含0、30、35、40 nmol/L PTX的完全培养液培养72 h后移除培养液,PBS洗涤1次,加入1 mL衰老相关β半乳糖苷酶(senescence-associated β-galactosidase,SA-β-gal)染色固定液室温固定15 min。吸除固定液,PBS洗涤3次,每次3 min。吸除PBS,每孔加入1 mL染色工作液,37 ℃孵育过夜。于倒置显微镜下观察衰老细胞,随机选取5个视野进行拍照,计算每个视野下衰老细胞百分率。

1.3 细胞分组与条件培养基的制备取BGC823细胞分为SASP-CM组、正常肿瘤细胞条件培养基(control-conditioned medium,CTR-CM)组和正常培养基(normal-conditioned medium,NOR-CM)组3组。SASP-CM组用SASP-CM+5% FBS培养细胞,CTR-CM组用CTR-CM+5% FBS培养细胞,NOR-CM组用含5% FBS的RPMI 1640培养液培养细胞。条件培养基的制备:(1)SASP-CM的制备。于6孔板中以2×105/孔的密度接种BGC823细胞,待细胞融合达80%后更换含35 nmol/L PTX的培养液继续培养72 h,换液,用无血清RPMI 1640培养液继续培养24 h后,12 000×g离心15 min收集上清,0.45 μm滤膜过滤,-80 ℃冰箱冻存备用。(2)CTR-CM的制备。于6孔板中以1×105/孔的密度接种BGC823细胞,用含二甲基亚砜(dimethyl surfoxide,DMSO)的完全培养液培养72 h后换液,用无血清RPMI 1640培养液继续培养24 h后,12 000×g离心15 min收集上清,0.45 μm滤膜过滤,-80 ℃冻存备用。

1.4 ELISA测定条件培养基中主要SASP因子的浓度取制备所得的SASP-CM和CTR-CM,按ELISA试剂盒操作说明检测各条件培养基中主要SASP因子的浓度。

1.5 检测细胞增殖活性取BGC823细胞悬液以5×103/mL的密度接种于96孔培养板内,培养6 h后吸去培养液,分别按各组要求加入相应的培养液继续培养,在24、48、72、96 h时每孔加入10 μL CCK-8,孵育2 h后使用Thermo ScientificTM MultiskanTM FC酶标仪检测450 nm波长处的光密度(D)值。各组设空白对照孔,实验重复3次,每组设5个复孔。

1.6 检测细胞克隆形成取各组细胞以300/孔的密度接种于6孔板中,实验设3个复孔;放置于37 ℃、5% CO2的培养箱中培养2周;当6孔板中出现肉眼可见的克隆时终止培养;吸出培养液,PBS洗涤1次,每孔加入500 μL甲醇固定5 min;吸出固定液,PBS洗涤,加适量吉姆萨染色液染色10 min;PBS洗涤、干燥,低倍镜下计数>50的克隆数,计算克隆形成率。

1.7 流式细胞术检测细胞周期和凋亡情况取各组细胞培养24、48、72、96 h后消化离心,以0.5 mL PBS重悬后迅速加入3.5 mL 70%预冷的乙醇,吹打均匀后4 ℃过夜;离心弃上清,用含有0.2 mg RNase A的1 mL PI/Triton X-100染色液重悬细胞,37 ℃染色15 min;应用流式细胞仪检测细胞周期。另取各组细胞培养24、48、72、96 h后消化离心,以0.5 mL结合缓冲液重悬,加入5 μL Annexin Ⅴ-EGFP混匀后,再加入5 μL PI,混匀;室温、避光反应15 min,上流式细胞仪检测细胞凋亡情况。

1.8 统计学处理采用Graphpad Prism 5.0软件进行数据分析。呈正态分布的计量资料用x±s表示,两组间比较采用非配对t检验,3组及以上样本的比较采用两两比较t检验。检验水准(α)为0.05。

2 结果 2.1 PTX诱导BGC823细胞衰老模型成功构建不同浓度PTX诱导BGC823细胞72 h后,显微镜下观察(图 1A)显示衰老细胞形态变得扁平、胀大、颗粒增多,细胞内SA-β-gal的活性增加,表明BGC823细胞衰老模型成功构建。由图 1B可见,浓度为35 nmol/L的PTX处理72 h时衰老细胞的比例最高,为(66.95±3.54)%,因此选用35 nmol/L PTX建立胃癌细胞衰老模型。

|

图 1 PTX诱导人胃癌细胞系BGC823衰老 Fig 1 Human gastric cancer cell lines BGC823 senescence induced by PTX A: Senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining results of BGC823 cells after treated with different concentrations of PTX for 72 h; B: Percentage of senescent cells after treated with different concentrations of PTX for 72 h. DMSO: Dimethyl sulphoxide; PTX: Paclitaxel. Scale bar=20 μm. **P < 0.01. n=3, x±s |

2.2 CTR-CM和SASP-CM中主要SASP因子浓度的比较

与CTR-CM相比,SASP-CM中IL-6、IL-8、CXC趋化因子配体1[chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1,CXCL1]、CC趋化因子配体2[chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2,CCL2]、γ干扰素(interferon γ, INF-γ)的浓度均升高(P均 < 0.01),而两组间IL-1β浓度差异无统计学意义,见图 2。

|

图 2 ELISA法检测SASP因子浓度 Fig 2 Concentrations of SASP factors detected by ELISA ELISA: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; SASP: Senescence-associated secretory phenotype; CTR: Control; CM: Conditioned medium; IL: Interleukin; CXCL1: Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1; CCL2: Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; INF-γ: Interferon γ. **P < 0.01 vs CTR-CM group. n=3, x±s |

2.3 各组BGC823细胞的增殖及克隆形成能力的比较

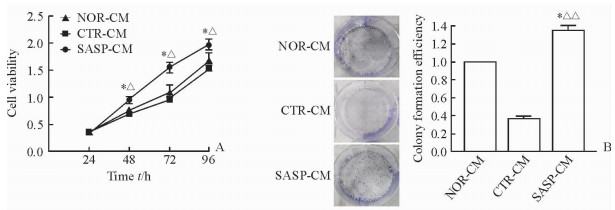

SASP-CM组细胞的增殖活性随着培养时间的延长呈现上升趋势,48、72、96 h时均高于CTR-CM组和NOR-CM组(P < 0.05,图 3A)。细胞克隆形成实验结果显示,SASP-CM组细胞的克隆形成率高于CTR-CM组(P < 0.01)和NOR-CM组(P < 0.05,图 3B),表明SASP-CM组BGC823细胞的增殖速度快于CTR-CM组和NOR-CM组。

|

图 3 SASP-CM促进人胃癌细胞系BGC823细胞增殖及克隆形成 Fig 3 SASP-CM promoted proliferation and colony formation abilities of human gastric cancer cell lines BGC823 A: Proliferation ability of BGC823 cells; B: Colony formation of BGC823 cells (Giemsa staining). CTR: Control; NOR: Normal; SASP: Senescence-associated secretory phenotype; CM: Conditioned medium. *P < 0.05 vs NOR-CM group (at same time point in Fig 3A); ΔP < 0.05, ΔΔP < 0.01 vs CTR-CM group (at same time point in Fig 3A). n=3, x±s |

2.4 各组BGC823细胞周期和凋亡率比较

流式细胞术结果(图 4)显示,培养BGC823细胞24、48、72、96 h后,SASP-CM组的S期细胞比例高于CTR-CM组和NOR-CM组,差异均有统计学意义(P均 < 0.01);而各组间G1期、G2期细胞比例以及细胞凋亡率差异均无统计学意义。

|

图 4 各组人胃癌细胞系BGC823的细胞周期及凋亡率 Fig 4 Percentage of cell phases and apoptosis of human gastric cancer cell lines BGC823 in each group A, C: Percentage of different phases of cells after culturing BGC823 cells for 72 h; B: Apoptosis of BGC823 cells after culturing for 72 h. CTR: Control; NOR: Normal; SASP: Senescence-associated secretory phenotype; CM: Conditioned medium. **P < 0.01 vs S phase of SASP-CM group.n=3, x±s |

3 讨论

长期以来,主流观点认为衰老是肿瘤进展过程中的障碍,是机体对抗肿瘤的重要手段之一,如衰老细胞通过SASP改变细胞微环境,招募中性粒细胞、巨噬细胞和自然杀伤细胞等免疫细胞到肿瘤病灶,从而杀死衰老细胞和肿瘤细胞[9-10]。然而,有研究表明衰老细胞分泌的SASP还可引起化疗耐药及肿瘤侵袭、转移;如Canino等[11]研究发现培美曲塞能诱导胸膜间皮瘤细胞发生衰老并分泌SASP,引起耐药及上皮细胞间质化。目前关于衰老细胞对肿瘤细胞增殖影响的研究主要集中于衰老成纤维细胞对上皮细胞增殖的影响,如在乳腺癌、前列腺癌中衰老的成纤维细胞促进乳腺上皮细胞、前列腺上皮细胞增殖[12],尚没有关于化学治疗诱导的胃癌衰老细胞对肿瘤增殖影响的报道。

新辅助化疗是临床上进展期胃癌常用的治疗手段之一。然而,部分患者经过化疗后肿瘤呈现报复性生长。我们前期通过对此类临床标本进行衰老染色发现肿瘤组织中存在衰老细胞(数据未发表)。为了探讨胃癌衰老细胞对肿瘤增殖的影响,本研究利用体外细胞培养体系建立衰老模型,用不同浓度PTX处理BGC823细胞不同时间,最终确定浓度为35 nmol/L的PTX处理72 h时胃癌衰老细胞比例最高,可建立稳定的衰老细胞模型,为下一步实验夯实了基础。

研究衰老细胞对肿瘤细胞增殖的影响,我们认为可以从两个方面来考虑,一是衰老细胞旁分泌对周围细胞增殖的影响,二是衰老细胞与周围细胞直接接触对周围细胞增殖的影响。本实验通过建立衰老细胞模型,并收集SASP-CM来研究胃癌衰老细胞旁分泌对人胃癌细胞系BGC823增殖的影响,结果发现衰老细胞条件培养对胃癌细胞的增殖具有促进作用,且是促进细胞周期进展而非抑制细胞凋亡。本实验不足之处在于未能进行细胞接触对细胞增殖影响的研究,这将是未来研究的另一方向。

衰老细胞条件培养基的主要成分在不同类型细胞中差异并不大,本研究通过ELISA检测发现SASP-CM中主要SASP因子IL-6、IL-8、CXCL1、CCL2、INF-γ的浓度均升高。目前,关于SASP因子促进肿瘤细胞增殖的机制研究较多,如衰老细胞可通过旁分泌IL-6与周围细胞表面IL-6R结合激活IL-6/IL-6R/Akt(Ser 473)/STAT3/Cyclin D1信号通路,从而促进上皮细胞、内皮细胞增殖等[13-14]。此外,IL-6和IL-8可协同促进炎性反应和细胞增殖。在乳腺癌中衰老成纤维细胞分泌的SASP因子CXCL1能促进乳腺上皮细胞增殖,而MMP与小鼠乳腺上皮细胞癌高度成瘤性相关,这些因子能激活细胞有丝分裂相关信号通路[15-16]。在前列腺癌中,衰老成纤维细胞分泌的双调蛋白也具有类似作用[17-18]。恶性黑色素瘤细胞高表达CXCR-2受体,在配体CXCL1和IL-8刺激下导致细胞增殖速度加快[13, 19]。本实验也表明,化学治疗药物PTX诱导的胃癌衰老细胞在一定层面上能通过SASP来促进肿瘤细胞生长。但SASP促进胃癌细胞增殖是一个整体,单因子研究并不能完全反应SASP因子的作用,因此,需进一步研究SASP-CM刺激下胃癌细胞发生的改变,如对SASP-CM组及CTR-CM组的细胞进行表达谱分析,从而确定下一步研究方向。

综上所述,胃癌衰老细胞能通过SASP促进肿瘤细胞增殖,SASP因子可能是肿瘤预后不良的重要指标。随着对SASP分子调控机制了解的深入,通过药物或者基因抑制SASP有望成为胃癌重要治疗手段之一。

| [1] | HAYFLICK L, MOORHEDA P S. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains[J]. Exp Cell Res, 1961, 25: 585–621. DOI: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6 |

| [2] | WILEY C D, CAMPISI J. From ancient pathways to aging cells-connecting metabolism and cellular senescence[J]. Cell Metab, 2016, 23: 1013–1021. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.010 |

| [3] | CAMPISI J, D'ADDA DI FAGAGNA F. Cellular senescence:when bad things happen to good cells[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2007, 8: 729–740. DOI: 10.1038/nrm2233 |

| [4] | RODIER F. Detection of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)[J]. Methods Mol Biol, 2013, 965: 165–173. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-62703-239-1 |

| [5] | HOENICKE L, ZENDER L. Immune surveillance of senescent cells-biological significance in cancer-and non-cancer pathologies[J]. Carcinogenesis, 2012, 33: 1123–1126. DOI: 10.1093/carcin/bgs124 |

| [6] | SAKAKIBARA H, YAMADA S. Vibration syndrome and autonomic nervous system[J]. Cent Eur J Public Health, 1995, 3(Suppl): 11–14. |

| [7] | REIMANN M, LEE S, LODDENKEMPER C, DÖRR J R, TABOR V, AICHELE P, et al. Tumor stroma-derived TGF-beta limits myc-driven lymphomagenesis via Suv39h1-dependent senescence[J]. Cancer Cell, 2010, 17: 262–272. DOI: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.043 |

| [8] | KRIMPENFORT P, BERNS A. Rejuvenation by therapeutic elimination of senescent cells[J]. Cell, 2017, 169: 3–5. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.014 |

| [9] | D'ADDA DI FAGAGNA F. Living on a break:cellular senescence as a DNA-damage response[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2008, 8: 512–522. DOI: 10.1038/nrc2440 |

| [10] | DI MITRI D, ALIMONTI A. Non-cell-autonomous regulation of cellular senescence in cancer[J]. Trends Cell Biol, 2016, 26: 215–226. DOI: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.10.005 |

| [11] | CANINO C, MORI F, CAMBRIA A, DIAMANTINI A, GERMONI S, ALESSANDRINI G, et al. SASP mediates chemoresistance and tumor-initiating-activity of mesothelioma cells[J]. Oncogene, 2012, 31: 3148–3163. DOI: 10.1038/onc.2011.485 |

| [12] | COPPÉ J P, DESPREZ P Y, KRTOLICA A, CAMPISI J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype:the dark side of tumor suppression[J]. Annu Rev Pathol, 2010, 5: 99–118. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102144 |

| [13] | MANGAHAS C R, DELA CRUZ G V, FRIEDMA-JIMÉNEZ G, JAMAL S. Endothelin-1 induces CXCL1 and CXCL8 secretion in human melanoma cells[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2005, 125: 307–311. DOI: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23820.x |

| [14] | YUN U J, RARK S E, JO Y S, KIM J, SHIN D Y. DNA damage induces the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway, which has anti-senescence and growth-promoting functions in human tumors[J]. Cancer Lett, 2012, 323: 155–160. DOI: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.04.003 |

| [15] | LIU D, HORNSBY P J. Senescent human fibroblasts increase the early growth of xenograft tumors via matrix metalloproteinase secretion[J]. Cancer Res, 2007, 67: 3117–3126. DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3452 |

| [16] | TSAI K K, CHUANG E Y, LITTLE J B, YUAN Z M. Cellular mechanisms for low-dose ionizing radiation-induced perturbation of the breast tissue microenvironment[J]. Cancer Res, 2005, 65: 6734–6744. DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0703 |

| [17] | KIM K H, RARK G T, LIM Y B, RUE S W, JUNG J C, SONN J K, et al. Expression of connective tissue growth factor, a biomarker in senescence of human diploid fibroblasts, is up-regulated by a transforming growth factor-beta-mediated signaling pathway[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2004, 318: 819–825. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.108 |

| [18] | BAVIK C, COLEMAN I, DEAN J P, KNUDSEN B, PLYMATE S, NELSON P S. The gene expression program of prostate fibroblast senescence modulates neoplastic epithelial cell proliferation through paracrine mechanisms[J]. Cancer Res, 2006, 66: 794–802. DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1716 |

| [19] | BOTTON T, PUISSANT A, CHELI Y, TOMIC T, GIULIANO S, FAJAS L, et al. Ciglitazone negatively regulates CXCL1 signaling through MITF to suppress melanoma growth[J]. Cell Death Differ, 2011, 18: 109–121. DOI: 10.1038/cdd.2010.75 |

2017, Vol. 38

2017, Vol. 38