2. 第二军医大学长海医院心内科, 上海 200433;

3. 解放军411医院心内科, 上海 200081

2. Department of Cardiology, Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200433, China;

3. Department of Cardiology, No.411 Hospital of PLA, Shanghai 200081, China

经皮冠状动脉介入治疗(PCI)术后为防止支架内血栓形成常规采用双联抗血小板及肝素抗凝治疗[1, 2]。但多个相关研究发现,PCI术后肝素抗凝不但不减少心血管事件,而且增加出血事件[3, 4, 5]。2011年、2012年美国心脏病学会基金会/美国心脏协会(ACCF/AHA)关于不稳定型心绞痛和非ST段抬高心肌梗死治疗的修订指南虽已明确,对无并发症、简单病变的患者,PCI术后可停用肝素抗凝治疗(ⅠB) [6, 7],但相关结论仍有争议。ATLAST研究[5]认为对大多数PCI术后患者,即使有复杂病变、支架血栓高危因素,抗血小板药物预防支架血栓已经足够,肝素抗凝会增加小出血的发生率。近年来的大规模临床试验结果也建议术后可允许医生根据经验决定小剂量抗凝剂肝素的使用[8, 9, 10]。高龄是PCI术后发生主要心脑血管不良事件的高危因素[11],老年患者又是术后出血高危人群[12, 13]。因此,探讨PCI术后肝素抗凝对不同年龄患者临床事件的影响具有重要的临床意义,也为PCI术后肝素个体化治疗提供重要依据。 1 资料和方法 1.1 病例选择

本研究是一项随机化、前瞻性临床试验。2010~2014年在第二军医大学长海医院入选PCI术后患者500例,安徽省宿州市立医院入选患者200例,根据计算机产生的随机数字号将入选患者随机分为伊诺肝素抗凝组和非抗凝组,术后根据年龄分为中年(<60岁)肝素抗凝组、非抗凝组,老年(60~74岁)肝素抗凝组、非抗凝组,高龄(≥75岁)肝素抗凝组、非抗凝组。

纳入标准:(1)年龄>18岁;(2)临床诊断为稳定型心绞痛、不稳定型心绞痛、非ST段抬高心肌梗死和ST段抬高心肌梗死;(3)愿意且能够接受规定的访视、治疗、实验室检查及其他研究活动;(4)择期手术者。排除标准:(1)严重肝、肾功能损害患者(GFR<30 mL/min·1.73 m2);(2)未能控制的高血压(≥180/110 mmHg,1 mmHg=0.133 kPa);(3)血红蛋白<9 g/L;(4)血小板计数小于100×109/L;(5)严重左心室功能不全(LVEF<30%或心源性休克患者);(6)正在服用其他抗凝药物如华法林;(7)股动脉穿刺部位血肿直径大于5 cm;(8)3个月内有出血性卒中史;(9)对阿司匹林、氯吡格雷、肝素及依诺肝素或其他低分子肝素过敏,有低分子肝素诱导的血小板减少症史(以往有血小板计数明显下降);(10)不能耐受抗血小板治疗患者;(11)血栓性病变、术中出现分支闭塞、冠脉夹层及慢血流或无复流等并发症以及需使用血小板糖蛋白Ⅱb/Ⅲa受体拮抗剂者。 1.2 用药方案

术前已接受长期阿司匹林冶疗的患者在PCI前服用阿司匹林100~300 mg。以往未服用阿司匹林的患者在24 h前给予阿司匹林300 mg;术前6 h或更早服用氯吡格雷者,给予氯吡格雷300 mg负荷剂量。如果术前6 h未服用氯吡格雷,给予600 mg。术前8~12 h用低分子肝素者,PCI前静脉追加依诺肝素0.3 mg/kg,如PCI术前8 h内接受过标准剂量依诺肝素皮下注射,无需追加依诺肝素。术后用药:术后患者常规服用阿司匹林100 mg/d、氯吡格雷75 mg/d,抗凝组于术后2 h加用依诺肝素(患者体质量<60 kg,依诺肝素使用40 mg,12 h 1次,皮下注射,共用3 d;体质量≥60 kg,依诺肝素使用60 mg,12 h 1次,皮下注射),非抗凝组术后不用肝素。根据患者实际情况,给予血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂(ACEI)、β受体阻滞剂、硝酸酯类、钙离子拮抗剂和他汀类治疗,以及加强对高危因素的控制。 1.3 PCI治疗

由2名有丰富介入经验的医师严格按规程进行操作,常规经桡动脉和股动脉行冠状动脉造影检查,采用定量冠状动脉造影(QCA)法测定冠状动脉病变处狭窄程度,参照1988年美国心脏病学会/美国心脏协会(ACC/AHA) 的病变分型标准对靶病变分型,靶病变直径狭窄≥70%,参考直径2.5~4.0 mm,按标准方法行冠状动脉内支架置入术,据病变情况选择不同支架。PCI 成功标准[14]:支架置入后残余狭窄< 20%,前向血流达到心肌梗死溶栓试验(TIMI)3级,无严重并发症。 1.4 研究终点及定义

主要终点事件:1年内主要心脑血管不良事件(major adverse cardiac and cerebral events,MACCEs),包括心源性死亡、心肌梗死(MI)、支架内血栓形成(ST)、靶血管再次血运重建术(target vessel revascularization,TVR)和脑卒中。次要终点事件:住院期间发生的出血事件。采用REPLACE-2研究标准,符合以下任一标准定义为严重出血: (1)重要脏器或组织出血,如颅内、眼内、腹膜后;(2)显性出血导致血红蛋白下降≥30 g/L或无显性出血血红蛋白下降≥40 g/L;(3)需要输2个单位以上全血或红细胞的出血。小出血:严重出血以外的出血事件包括穿刺点出血、皮肤淤血、咯血、消化道出血、血尿、牙龈出血等。心肌梗死[15]:PCI相关性心肌梗死为基线肌钙蛋白水平正常的患者,在接受PCI治疗后48 h内cTn水平升高至超过参考值上限(URL)第99百分位的5倍;或者基线水平升高的患者,cTn水平上升超过20%,且保持稳定或逐渐下降,同时还要求出现下列事件中的1种:症状提示心肌缺血;新出现缺血性心电图改变;血管造影结果与PCI并发症相吻合;或有存活心肌新损失或新出现局部心壁运动异常的影像学证据。急性心肌梗死:检测到心脏生物标志物水平上升和(或)下降超过URL第99百分位,且符合下列条件中的至少1项:有缺血症状;新出现或很可能新出现ST段显著抬高/T波改变或新出现左束支传导阻滞(LBBB);心电图出现病理性Q波;有存活心肌新损失或新出现局部心壁运动异常的影像学证据;血管造影或尸检发现冠状动脉内血栓。 1.5 统计学处理

所有资料均被录入病例报告表。随访方式包括门诊复查、再住院和(或)电话随访,由专人判断并记录终点事件。随访时间为患者在PCI术后住院期间以及术后1年。采用SPSS 18.0统计软件,分类变量的描述用频数(%),比较方法采用χ2检验,计量资料描述用x±s表示,如正态分布、方差齐性采用t检验,否则采用非参数检验,检验水准(α)为 0.05。 2 结 果 2.1 患者基线资料的比较

结果表明:入选700例患者中完成随访687例,其中中年患者238例(34.6%),平均(51.3±6.6)岁;老年患者331例(48.2%),平均(66.4±4.2)岁;高龄患者118例(17.2%),平均(77.2±1.8)岁。老年组女性患者比例高于中年组(P<0.01),高龄组女性患者比例分别高于老年组、中年组(P<0.01);老年组及高龄组平均体质量均低于中年组(P<0.01);高龄组平均体质指数低于中年组(P<0.01);老年组平均体质指数低于中年组(P<0.05);老年组肾小球滤过率小于60 mL/min·1.73 m2的比例高于中年组(P<0.05);高龄组肾小球滤过率小于60 mL/min·1.73 m2的比例高于中年组(P<0.01),各年龄组内抗凝组与非抗凝组患者基线资料差异无统计学意义。 2.2 术前、术后用药情况对比

结果表明:术后所有患者均使用阿司匹林、氯吡格雷以及他汀类调脂药。PPI、ACEI、ARB、β受体阻滞剂、硝酸酯类、钙离子拮抗剂用药根据患者病情需要用药。中年组、老年组、高龄组间,以及各年龄组内抗凝组与非抗凝组间患者术前、术后用药差异均无统计学意义(P<0.05)。 2.3 冠状动脉造影及PCI术结果

结果表明:高龄组C型病变比例高于老年组及中年组(P<0.05);高龄组慢性闭塞病变及多支血管病变比例高于中年组(P<0.05)。 2.4 住院期间主要临床事件的发生率 2.4.1 平均住院天数

中年抗凝组平均住院天数为(6.33±1.52) d,非抗凝组住院天数为(5.58±1.01) d,差异无统计学意义(P=0.052)。老年抗凝组平均住院天数(6.58±1.31) d,非抗凝组住院天数(5.75±1.29) d,非抗凝组住院天数少于抗凝组(P=0.032)。高龄抗凝组平均住院天数(6.79±1.35) d,非抗凝组住院天数(5.96±1.08) d,非抗凝组住院天数少于抗凝组(P=0.023)。 2.4.2 MACCEs

住院期间中年组、老年组、高龄组MACCEs的发生率分别是1.3%、2.4%、3.4%,差异无统计学意义。各年龄组抗凝组与非抗凝组间MACCEs以及支架内血栓、死亡、靶血管重建、脑卒中的发生率差异均无统计学意义 (表 1)。

|

|

表 1 住院期间主要临床事件发生率 Tab 1 Main clinical events during hospital |

中年组、老年组、高龄组住院期间小出血发生率分别为20.2%、29.9%、34.7%,随着年龄的增加而增高。老年组、高龄组小出血发生率较中年组增高(P<0.05),中年抗凝组与非抗凝组小出血发生率差异无统计学意义,老年、高龄患者抗凝组小出血发生率均高于非抗凝组(P<0.05)。中年组、老年组、高龄组住院期间大出血发生率分别是1.2%、1.5%、1.7%,各年龄段抗凝与非抗凝组患者大出血发生率差异无统计学意义 (表 1)。 2.4.4 DVT事件发生率

住院期间,各年龄段抗凝组与非抗凝组间DVT发生率差异均无统计学意义(表 1)。 2.5 PCI术后1年内主要临床事件发生率

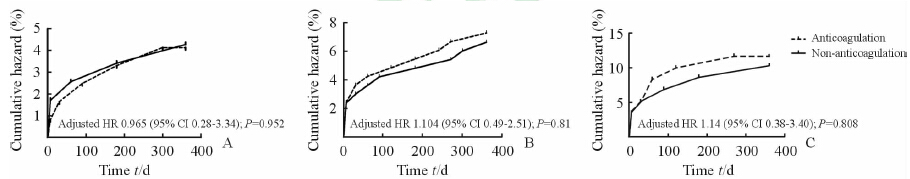

随访1年时中年组、老年组、高龄组MACCEs发生率分别是4.2%、6.9%、11%,高龄组MACCEs发生率高于中年组(P<0.05)。各年龄段抗凝组与非抗凝组间MACCEs、支架内血栓、死亡、靶血管重建、脑卒中发生率差异均无统计学意义(表 2)。各年龄段抗凝组与非抗凝组1年时MACCEs累计发生率差异均无统计学意义(图 1)。

|

图 1 不同年龄段患者PCI术后1年内两组患者间的累积风险 Fig 1 Cumulative hazard of two groups in one year after PCI among different ages A:Age <60 years group; B:60 years≤ age <75 years group; C:Age ≥75 years group |

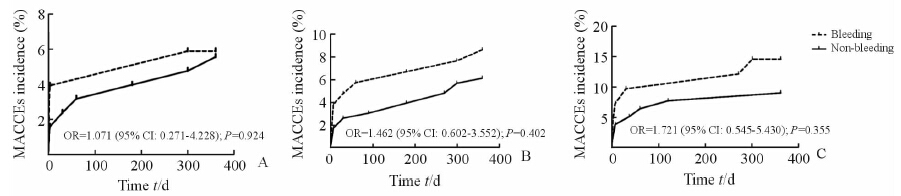

结果(图 2)显示:各年龄组住院期间小出血事件与术后1年内MACCEs均无相关性。

|

图 2 不同年龄组患者出血与MACCEs的相关性 Fig 2 The relationship between bleeding and MACCEs among different ages A:Age <60 years group; B:60 years≤ age <75 years group;C:Age ≥75 years group |

近年,随着强效抗栓药物的应用,PCI术后缺血并发症显著减少,但出血事件却随之增加,出血事件同样会给患者预后带来严重不利影响。多个研究认为PCI术后出血事件与增加的死亡、心梗等不良心血管事件有独立的相关性[16, 17, 18]。老年患者PCI后出血并发症的增加已经受到了广泛关注。Rao等[19]研究发现,大于 65岁的PCI术后患者出血发生率为3.1%。肝素抗凝是PCI术后传统的治疗方案,为减少出血,指南已不常规推荐PCI术后使用肝素抗凝,但指南对PCI术后明确停用肝素抗凝仅局限于无并发症、简单病变的患者。本研究共收集了700例PCI术后患者,其中C型病变占44%,尝试通过PCI术后肝素抗凝对不同年龄患者临床事件的影响,进一步为肝素个体化抗凝治疗提供实验依据。

|

|

表 2 12个月时主要心脑血管不良事件 Tab 2 MACCEs at one year after PCI |

本研究中住院期间中年组、老年组、高龄组小出血的发生率分别是20.2%、29.9%、34.7%,随着年龄的增加而增高,老年组、高龄组小出血发生率较中年组显著增高,中年患者肝素抗凝组与非抗凝组小出血发生率无明显差异,而老年组、高龄组肝素抗凝患者小出血发生率均高于非抗凝组。PCI术后肝素抗凝增加老年组、高龄组患者小出血风险考虑与以下因素有关:(1)高龄组、老年组患者容易合并局部动脉病变,血管内皮细胞再生能力下降,血管脆性增加,容易造成血管破裂出血。(2)本研究中老年组及高龄组体质量、体质指数低于中年组,而研究中肝素使用剂量只分为两种:体质量<60 kg,依诺肝素使用40 mg;体质量≥60 kg,依诺肝素使用60 mg。对老年及高龄患者而言可能会存在依诺肝素剂量过大,增加了出血的风险。Ang等[20]研究显示低体质量、低BMI患者与抗凝、抗血小板治疗后出血有相关性,与本研究结果一致。(3)老年组、高龄组女性比例较中年组高也是抗凝出血事件较高的原因之一。多个研究证实PCI术后女性患者出血并发症高于男性患者[21, 22]。Lichtmar等[23]研究显示,不论是老年女性还是年轻女性,PCI术后各种并发症特别是出血并发症均较男性高。本研究中,中年组、老年组、高龄组女性比例分别是14.1%、50%、77.9%,老年组及高龄组患者中女性比例明显高于中年组,因而使用肝素抗凝治疗后可能会导致出血事件增加。(4)肝素可增加慢性肾功能不全患者的出血事件。低分子肝素主要通过肾脏清除,合并肾功能不全的患者半衰期延长。采用依诺肝素后抗Ⅹa活性与肌酐清除密切相关[24]。REPLACE-2 研究显示:肌酐清除率<30 mL/min的患者出血风险增加1.72倍[25]。因此,对于严重肾功能衰竭(肌酐清除率小于30 mL/min)患者,依诺肝素的用量至少应减少50%,以免因蓄积而导致出血[26]。本研究中肾小球滤过率<60 mL/min·1.73 m2的患者比例在中年组占3.7%,而在老年组、高龄组中分别占9.6%、16.7%,导致老年组、高龄组患者使用肝素抗凝后出血事件增加。(5)高龄组患者慢性闭塞病变及多支血管病变比例较高,手术时间较长,术中使用肝素量增加,术后予以肝素抗凝也会增加出血风险。

本研究中,中年组、老年组、高龄组住院期间大出血发生率分别是1.3%、1.5%、1.7%,3组间以及各抗凝组与非抗凝组大出血的比例差异均无统计学意义,且均低于目前系列研究[27, 28, 29]结果。这可能与本研究中高达74%患者经桡动脉途径[30]行PCI有关。本研究中各年龄组出血事件与术后1年时MACCEs无相关性,可能与本研究中出血事件以小出血为主有关[31, 32]。

本研究中PCI术后住院期间中年组、老年组、高龄组MACCEs的发生率分别是1.3%、2.4%、3.4%,总发生率为3.9%,随访1年时,各组MACCEs的发生率分别是4.2%、6.9%、11%,总发生率为11.9%。各组PCI术后肝素抗凝与非抗凝患者住院期间以及术后1年时死亡、ST、TVR、脑卒中、心肌梗死以及全部MACCEs差异均无统计学意义。Kaplan-Meier分析显示各年龄组抗凝与非抗凝患者PCI术后1年时MACCEs的累积风险差异无统计学意义。研究结果提示对于不同年龄患者,PCI术后肝素抗凝并不减少MACCEs的发生率。本研究中1年时高龄患者MACCEs的发生率高于中年患者(11% vs 4.2%),与国外相关研究[33, 34]结果基本一致。这可能与高龄患者冠脉慢性闭塞病变、多支血管病变比例较高以及高龄患者重要脏器代偿不全,抗病能力及免疫机能的下降等因素有关。

DVT是多因素综合作用的结果,高龄、肢体制动、手术或创伤、恶性肿瘤、妊娠、既往静脉血栓病史等被认为是DVT高危因素。低分子肝素与普通肝素相比有较强的抗血栓形成作用[35]。本研究发现,不论是中年患者还是老年患者、高龄患者,PCI术后未予肝素抗凝并不增加DVT的发生率,这可能与PCI术后卧床时间短及术后下床活动较早等因素有关。当然,本研究样本量较少,住院期间发生DVT的例数较少,对研究结果可能会产生一定的影响。

综上所述,PCI术后不予肝素抗凝并不增加MACCEs的发生率,而且减少老年、高龄患者住院期间小出血发生率及住院天数,同时也不增加住院期间DVT的发生率。结果提示,术中若未发生慢血流、无复流以及冠脉夹层等具有血栓高危因素的并发症,PCI术后患者特别是老年和高龄患者无需抗凝治疗。当然,本研究样本量有限,相关结论仍有待进一步研究证实。

| [1] | ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina)[S]. (2002-03-15). http://www.acc.org/clinical/guidelines/unstable/unstable.pdf. |

| [2] | ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ SCAI Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention)[S]. (2005-09-01). http://www.acc.org/clinical/guidelines/percutaneous/update/index.pdf. |

| [3] | Karrillon G J, Morice M C, Benveniste E, Bunouf P, Aubry P, Cattan S, et al. Intracoronary stent implantation without ultrasound guidance and with replacement of conventional anticoagulation by antiplatelet therapy. 30-day clinical outcome of the French Multicenter Registry[J].Circulation,1996,94:1519-1527. |

| [4] | Harjai K J, Stone G W, Grines C L, Cox D A, Garcia E, Tcheng J E, et al. Usefulness of routine unfractionated heparin infusion following primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction in patients not receiving glycoprotein Ⅱb/Ⅲa inhibitors[J].Am J Cardiol,2007,99:202-207. |

| [5] | Batchelor W B, Mahaffey K W, Berger P B, Deutsch E, Meier S, Hasselblad V, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of enoxaparin after high-risk coronary stenting: the ATLAST trial[J].J Am Coll Cardiol,2001,38:1608-1613. |

| [6] | Wright R S, Anderson J L, Adams C D, Bridges C R, Casey D E Jr, Ettinger S M, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update of the Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (updating the 2007 guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons[J].J Am Coll Cardiol,2011,57:1920-1959. |

| [7] | Jneid H, Anderson J L, Wright R S, Adams C D, Bridges C R, Casey D E Jr, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines[J].J Am Coll Cardiol,2012,60:645-681. |

| [8] | Stone G W, McLaurin B T, Cox D A, Bertrand M E, Lincoff A M, Moses J W,et al. Bivalirudin for patients with acute coronary syndromes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2006,355:2203-2216. |

| [9] | Stone G W,Ware J H,Bertrand M E,Lincoff A M,Moses J W,Ohman E M,et al.Antithrombotic strategies in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing early invasive management: one-year results from the ACUITY trial[J].JAMA,2007,298:2497-2506. |

| [10] | Stone G W, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, Peruga J Z, Brodie B R, Dudek D, et al. Bivalirudin during primary PCI in acute myocardial infarction[J].N Engl J Med,2008,358:2218-2230. |

| [11] | SYNERGY Executive Committee. Superior Yield of the New strategy of Enoxaparin, Revascularization and GlYcoprotein Ⅱb/Ⅲa inhibitors. The SYNERGY trial: study design and rationale[J]. Am Heart J, 2002,143:952-960. |

| [12] | Piper W D, Malenka D J, Ryan T J Jr, Shubrooks S J Jr, O’Connor G T, Robb J F, et al. Predicting vascular complications in percutaneous coronary interventions[J].Am Heart J,2003,145:1022-1029. |

| [13] | Assali A R, Moustapha A, Sdringola S, Salloum J, Awadalla H, Saikia S, et al. The dilemma of success: percutaneous coronary interventions in patients > or = 75 years of age-successful but associated with higher vascular complications and cardiac mortality[J].Catheter Cardiovasc Interv,2003,59:195-199. |

| [14] | 中华医学会心血管病学分会,中华心血管病杂志编辑委员会.经皮冠状动脉介入治疗指南(2009)[J].中华心血管杂志,2009,37:4-25. |

| [15] | Costa F M, Ferreira J, Aguiar C, Dores H, Figueira J, Mendes M. Impact of ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF universal definition of myocardial infarction on mortality at 10 years[J].Eur Heart J,2012,33:2544-2550. |

| [16] | Lopes R D, Subherwal S, Holmes D N, Thomas L, Wang T Y, Rao S V, et al. The association of in-hospital major bleeding with short-, intermediate-, and long-term mortality among older patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction[J].Eur Heart J, 2012,33:2044-2053. |

| [17] | Chhatriwalla A K, Amin A P, Kennedy K F, House J A, Cohen D J, Rao S V, et al. Association between bleeding events and in-hospital mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention[J].JAMA, 2013,309:1022-1029. |

| [18] | Ndrepepa G, Neumann F J, Schulz S, Fusaro M, Cassese S, Byrne R A, et al. Incidence and prognostic value of bleeding after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients older than 75 years of age[J].Catheter Cardiovasc Interv, 2014,83:182-189. |

| [19] | Rao S V, Dai D, Subherwal S, Weintraub W S, Brindis R S, Messenger J C, et al. Association between periprocedural bleeding and long-term outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention in older patients[J].JACC Cardiovasc Interv,2012,5:958-965. |

| [20] | Ang L, Palakodeti V, Khalid A, Tsimikas S, Idrees Z, Tran P, et al. Elevated plasma fibrinogen and diabetes mellitus are associated with lower inhibition of platelet reactivity with clopidogrel[J].J Am Coll Cardiol,2008,52:1052-1059. |

| [21] | Berger J S, Sanborn T A, Sherman W, Brown D L. Influence of sex on in-hospital outcomes and long-term survival after contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention[J].Am Heart J,2006,151:1026-1031. |

| [22] | Chacko M, Lincoff A M, Wolski K E, Cohen D J, Bittl J A, Lansky A J, et al. Ischemic and bleeding outcomes in women treated with bivalirudin during percutaneous coronary intervention: a subgroup analysis of the Randomized Evaluation in PCI Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events (REPLACE)-2 trial[J].Am Heart J,2006,151:1032,e1-e7. |

| [23] | Lichtman J H, Wang Y, Jones S B, Leifheit-Limson E C, Shaw L J, Vaccarino V, et al. Age and sex differences in inhospital complication rates and mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention procedures: evidence from the NCDR(®)[J].Am Heart J,2014,167:376-383. |

| [24] | The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 11A Trial Investigators. Dose-ranging trial of enoxaparin for unstable angina: results of TIMI 11A[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol,1997,29:1474-1482. |

| [25] | Chew D P, Lincoff A M, Gurm H, Wolski K, Cohen D J, Henry T, et al. Bivalirudin versus heparin and glycoprotein Ⅱb/Ⅲa inhibition among patients with renal impairment undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (a subanalysis of the REPLACE-2 trial)[J].Am J Cardiol,2005,95:581-585. |

| [26] | Becker R C, Spencer F A, Gibson M, Rush J E, Sanderink G, Murphy S A, et al. Influence of patient characteristics and renal function on factor Ⅹa inhibition pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics after enoxaparin administration in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes[J].Am Heart J,2002,143:753-759. |

| [27] | Marso S P, Amin A P, House J A, Kennedy K F, Spertus J A, Rao S V, et al. Association between use of bleeding avoidance strategies and risk of periprocedural bleeding among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention[J].JAMA,2010,303: 2156-2164. |

| [28] | Ndrepepa G, Berger P B, Mehilli J, Seyfarth M, Neumann F J, Schömig A, et al. Periprocedural bleeding and 1-year outcome after percutaneous coronary interventions: appropriateness of including bleeding as a component of a quadruple end point[J].J Am Coll Cardiol,2008,51:690-697. |

| [29] | Moscucci M, Fox K A, Cannon C P, Klein W, López-Sendón J, Montalescot G, et al. Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE)[J].Eur Heart J,2003,24:1815-1823. |

| [30] | Bagur R, Bertrand O F, Rodés-Cabau J, Rinfret S, Larose E, Tizón-Marcos H, et al. Comparison of outcomes in patients > or =70 years versus <70 years after transradial coronary stenting with maximal antiplatelet therapy for acute coronary syndrome[J].Am J Cardiol,2009,104:624-629. |

| [31] | Vavalle J P, Rao S V. Impact of bleeding complications on outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention[J]. Interv Cardiol 2009,1:51-62. |

| [32] | Eikelboom J W, Mehta S R, Anand S S, Xie C, Fox K A, Yusuf S. Adverse impact of bleeding on prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes[J].Circulation,2006,114:774-782. |

| [33] | Velders M A, James S K, Libungan B, Sarno G, Fröbert O, Carlsson J, et al. Prognosis of elderly patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention in 2001 to 2011: A report from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR) registry[J].Am Heart J,2014,167:666-673. |

| [34] | Singh M, Rihal C S, Lennon R J, Garratt K N, Mathew V, Holmes D R Jr. Prediction of complications following nonemergency percutaneous coronary interventions[J].Am J Cardiol,2005,96:907-912. |

| [35] | 董春峰,王苏杭.低分子肝素在预防大隐静脉曲张术后患肢深静脉血栓形成中的作用[J].医学综述,2012,18:2673. |

2015, Vol. 36

2015, Vol. 36