银屑病是一种慢性、复发性、炎症性皮肤疾病,大约影响世界人口的2%~3%[1],其中90%是斑块型银屑病。它主要累及患者皮肤和关节,具有角蛋白细胞的过度增生和异常分化,血管膨胀、增生,以及T细胞、树突状细胞、巨噬细胞、自然杀伤细胞、中性粒细胞等炎症细胞浸润等特点[2, 3]。目前认为T细胞是银屑病发病的关键因子,此外,还有证据表明链球菌感染与银屑病之间有密切联系[4]。银屑病型关节炎是银屑病的一种特殊类型,目前研究显示银屑病患者同时具有银屑病型关节炎的比例为6%~42%[5];它能影响脊柱、外周的关节和肌腱末端,具有全身性炎症和广泛的滑膜炎表征,导致关节软骨腐蚀和骨质破坏[6, 7]。作为活动性炎症的结果,渐进的损害始于疾病早期,多达47%的患者平均间隔2年发生影像学的进展,最终引起不可逆的残疾[8]。

通常银屑病发生8~10年以后会衍生出银屑病型关节炎[9],但有一些银屑病型关节炎的患者并不表现银屑病的皮肤表征。由于两者都是免疫细胞介导的慢性、炎症性疾病,且有着相似的发病机制,共同治疗可以使药物不良反应和患者的经济负担达到最小化[9]。

本文概述和总结近年来在银屑病和银屑病关节炎的治疗发展中的小分子化学物质和生物药物(蛋白质类、修饰的蛋白质类、单克隆抗体和相关产物),重点介绍新药的作用机制、有效性和不良反应。 1 银屑病和银屑病型关节炎发病机制的相似之处

银屑病和银屑病型关节炎的发病机制都涉及到先天和获得性免疫。T细胞活化是银屑病发病机制的关键,尤其是Th1、Th17和Th22细胞在银屑病皮损组织中的正调节[10, 11]。研究者在银屑病皮损处发现高表达的IFN-γ、TNF-α和IL-12,它们是Th1炎症通路的关键细胞因子[12]。活化的T细胞由表皮向真皮迁移,与树突状细胞和组织细胞相互作用产生IL-12和IL-23。IL-23参与初始T细胞分化成Th17细胞的过程,随后Th17细胞分泌IL-17A、IL-17F、IL-6、IL-22、IL-26和TNF-α[13]。上调的Th22细胞增加了IL-22和TNF-α分泌[14],导致IL-22刺激角质形成细胞的增殖[15]。

与皮肤相似,在银屑病型关节炎中关节和发炎的肌腱末端也有大量的T细胞浸润,它们是由初始CD4+T细胞分化而来[16, 17]。T细胞衍生的细胞因子中有一些与在银屑病皮损组织中的细胞因子相似,包括TNF-α、IL-1β、IL-2和IFN-γ[18]。这些促炎的细胞因子刺激细胞黏附分子的产生,导致T细胞通过血管内皮向滑膜迁移。在关节中,TNF-α和活化T细胞释放的IL-1及间质细胞刺激滑液增生,引起基质金属蛋白酶释放,导致关节损害[19]。研究已发现大量的Th17细胞存在于银屑病型关节炎患者的滑膜组织和滑液中[20]。

全组基因研究增进了对银屑病和银屑病型关节炎遗传易感性基础的理解,研究表明有10个基因与两者发病都有关,包括人白细胞位点-C抗原(HLA-C)、IL-12B、IL-23R和人源全长重组蛋白(TRAF3IP2)[21]。 2 治疗银屑病和银屑病型关节炎的生物药物

治疗银屑病和银屑病型关节炎的传统药物包括糖皮质激素、甲氨蝶呤、环孢素、非类固醇类抗炎药和改变病情的抗风湿药物等,由于它们口服剂型方便,成本较低,因此在生物药物到来之际并不排除系统药物的使用。但是当一线治疗失败后,越来越多的生物药物用于银屑病和银屑病型关节炎的诊治,几个新型生物技术产物在疾病的治疗发展中诞生,包括抗TNF、抗IL-17、抗IL-12/IL-23和抗IL-17受体药物。 2.1 TNF抑制剂

赛妥珠单抗(CZP)是一个较新的与聚乙二醇共价结合的TNF阻滞药,与其他单克隆抗体(英夫利昔单抗和阿达木单抗)不同,它缺乏一个Fc片段且诱导抗体依赖细胞介导的细胞毒性[22]。一项随机、Ⅱ期临床试验结果表明,中、重度斑块状银屑病患者给予赛妥珠单抗200 mg或400 mg,至第12周,2组银屑病皮损面积和严重度指数75(PASI 75)的下降比例分别为75%和83%,安慰剂组仅为7%[22]。对银屑病型关节炎,Mease 等[23]的研究显示达到PASI 75反应的患者在赛妥珠单抗组中明显高于安慰剂组。最常见的不良反应是轻或中等的鼻咽炎、头痛和皮肤瘙痒症,并且在撤药以后复发的患者也能够重新获得积极的临床反应[22]。 2.2 抗IL-12/IL-23 p40药物

IL-12和IL-23是异二聚体蛋白质,共有一个p40亚基。IL-12参与细胞向Th1方向分化,而IL-23诱导Th17细胞的激活及其相关因子的释放。

乌司奴单抗是一个全人源化IgG1单克隆抗体,与p40亚单位结合,从而阻断IL-12和IL-23细胞因子的生物活性,减少皮损处IL-12、IL-23和IFN-γ mRNA的表达。同时它也抑制IL-12和IL-23诱导IFN-γ、IL-17A、 TNF-α和IL-2的分泌[24]。乌司奴单抗能用于中重度银屑病的治疗,也有Ⅱ期和Ⅲ期双盲、安慰剂对照的临床试验评价了其对中重度斑块状银屑病的有效性[25]。另一项随机、双盲、多中心、安慰剂对照的临床试验表明,乌司奴单抗可显著减轻活动性银屑病关节炎患者的症状和体征,对银屑病关节炎具有良好的临床疗效和安全性,且大多数不良反应为轻度的,一般为鼻咽炎、上呼吸道感染和疲劳[26]。 2.3 IL-17抑制剂

IL-17A也被称为IL-17,是一个由Th17细胞分泌的促炎细胞因子。IL-17A在银屑病中的主要来源是皮肤炎性浸润的T细胞[27]。研究已经证明,IL-17RA缺乏的小鼠不能形成咪喹莫特(IMQ)诱导的类似银屑病的病理特征,其表皮中IL-17A、IL-17F和IL-23的表达也有所减少[28]。因此,通过抑制IL-17RA信号转导可有效治疗银屑病。

苏金单抗(AIN-457)是一个全人源化IgG1单克隆抗IL-17抗体,能选择性中和IL-17A。在36例银屑病患者中单独给予静脉注射苏金单抗3 mg/kg,12周以后PASI平均减少63%,明显高于安慰剂组(减少9%),差异有统计学意义(P=0.000 5)[29]。在另一项研究中,42例银屑病型关节炎患者以2∶1注射苏金单抗(10 mg/kg)或安慰剂,在第6周,两者主要终点指标——美国风湿病学会(ACR)反应率差异有统计学意义[30]。在诱导期和持续期大多数不良反应是轻度或中度的,主要是鼻咽炎、头痛和上呼吸道感染[31]。 2.4 IL-17受体抑制剂

Brodalumab(AMG-827)是一个完全人源单克隆抗体,能结合IL-17受体并阻断其信号通路,其在风湿性关节炎、克罗恩病和银屑病的临床试验已经完成。Ⅱ期、双盲、安慰剂对照、剂量梯度试验证实,brodalumab可改善第12周PASI得分,至少75% PASI病损和至少90% PASI病损得到改善的患者比例有所提高,证明brodalumab可明显改善银屑病症状[32]。最常见的不良反应是鼻咽炎、上呼吸道感染和注射部位红斑。一项Ⅱ期研究对brodalumab治疗银屑病型关节炎的疗效及安全性也进行了评价[33]。 3 治疗银屑病和银屑病型关节炎的小分子药物

当今研究方向已发展到调控细胞内信号来控制炎症介质的表达。在体内,所有细胞内信号和对环境因素的反应都是由信号通路的组分或“第二信使”介导,诸如环磷腺苷(cAMP)[34]。

磷酸二酯酶(PDE)水解cAMP产生一磷酸腺苷(AMP)。PDE有8个家族,其中PDE4家族在免疫细胞中是最普遍的,由角蛋白细胞和软骨细胞表达[35]。PDE4抑制剂增加细胞内cAMP浓度,随后减少促炎细胞因子如TNF-α、IFN-γ和IL-2,减少外周血单核细胞和T细胞的产生[36],并且增加抗炎介质,如IL-10[37]。

酪氨酸蛋白激酶(JAKs)由JAK1、JAK2、JAK3和Tyk2组成[38]。抑制JAK1和JAK3共有的γ链,可导致一些细胞因子如IL-2、IL-4、IL-7、IL-9、IL-15和IL-21表达受阻[39]。这些细胞因子对淋巴细胞的生长、作用和存活至关重要,其信号抑制剂可调节免疫反应[40]。 3.1 PDE抑制剂

阿瑞米拉(CC-10004)是新颖的、可口服的小分子,特定靶点在PDE4。在小鼠银屑病模型中,它能抑制TNF-α、IL-12和IL-23细胞因子的表达,也抑制自然杀伤细胞和角蛋白细胞的反应[41]。

在银屑病型关节炎的治疗中,一项Ⅱ期、多中心、随机、双盲、安慰剂对照研究表明,阿瑞米拉20 mg、每日2次和每日40 mg与安慰剂组差异有统计学意义且普遍耐受良好[42]。美国FDA于2014年3月21日批准阿瑞米拉用于成人活跃型银屑病关节炎[43]。常见不良反应有腹泻、头痛、反胃、疲劳和鼻咽炎。 3.2 JAK抑制剂 3.2.1 托法替尼(CP-690,550)

托法替尼是口服的JAK抑制剂,选择性抑制JAK3和(或)JAK1相关的异二聚体受体的信号[44]。在Ⅰ期和Ⅱ期临床试验中已证实,它在治疗风湿性关节炎中取得较为满意的疗效[45],并在试验中发现伴发银屑病症状的改善,这为银屑病关节炎的临床试验提供了依据。

最近,一项Ⅱb期、12周、剂量梯度试验研究表明,托法替尼能显著改善中重度斑块型银屑病患者的皮肤表征且具有良好耐受性。在第12周每日2次给药的患者中PASI改善至少75%的患者有较高的比例:25%(2 mg)、40.8%(5 mg)和66.7%(15 mg),相比安慰剂组(2%)差异有统计学意义[39]。不良反应有感染、剂量依赖性血浆低密度脂蛋白升高以及总胆固醇、血红蛋白和中性粒细胞减少等。 3.2.2 INCB018424

INCB018424是一个局部用药物,能优先抑制JAK1和JAK2[46],通过阻断银屑病发病机制中JAK-STAT3信号转导通路,从而抑制其下游因子如IL-17、IL-20、IL-22和IFN-γ的表达[47]。INCB018424具有很好的耐受性,据报道其不良反应较轻,如皮肤的刺痛、瘙痒、疼痛、干燥和剥落等[47]。由于银屑病型关节炎发病也与JAK-STAT3通路有关,故推测该药也能用于银屑病关节炎的治疗。 4 治疗原则

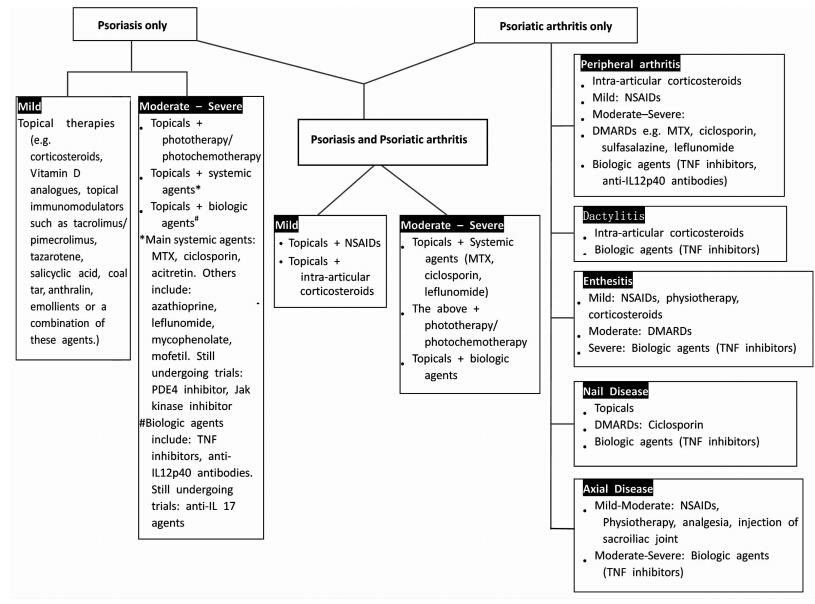

根据现有的治疗方法汇总出银屑病和(或)银屑病型关节炎患者的药物治疗原则,见图 1。传统治疗银屑病通常使用的方法包括:(1)局部用药,皮质类固醇、煤焦油、维生素D类似物(例如卡泊三醇);(2)光疗法,窄谱中波紫外线光疗法、补骨脂素长波紫外线光疗法;(3)系统性用药,口服维生素A酸类(例如阿维a)、甲氨蝶呤和环孢素。治疗银屑病型关节炎一般使用非类固醇类抗炎药、关节内的皮质类固醇注射剂和改变病情的抗风湿药物,如柳氮磺胺吡啶。但是这些传统治疗药物有一定局限性,如甲氨蝶呤和环孢素在长期服用后会导致严重的肝损害等。

| 图 1 建议银屑病和(或)银屑病型关节炎患者治疗原则 Fig 1 Suggested treatment algorithm for patients with psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis MTX: Methotrexate; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; IL:Interleukin; PDE:Phosphodiesterase; NSAIDs:Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; DMARDs:Disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs |

随着对银屑病和银屑病型关节炎发病机制的深入研究和现代制药工程技术的迅猛发展,越来越多的生物药物和小分子化学物质应运而生。本文阐述了近年来临床试验发表的新型产物,此外仍有一些药物不断问世,诸如新的T细胞活化和作用的抑制剂(阿巴西普,百时美施贵宝,纽约,美国)、p38抑制剂(BMS582949,百时美施贵宝)、IL-22抑制剂(非扎奴单抗,辉瑞公司,纽约,美国)、 组织蛋白酶S抑制剂(RWJ-445380,强生,圣地亚哥,美国)、1-磷酸-1-鞘氨醇受体催化剂(ACT-128800,爱可泰隆,阿尔施维尔,瑞士)及新的蛋白激酶C抑制剂(AEB071,诺华,巴塞尔,瑞士)[48, 49]。虽然这些药物大多数还不能确定何时上市,但令人鼓舞的是治疗银屑病和银屑病型关节炎备选药物的数量日益增加,这不仅给患者带来了福音,也为个体化治疗提供了新的机遇。

| [1] | Parisi R, Symmons D P, Griffiths C E, Ashcroft D M; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2013, 133:377-385. |

| [2] | Conigliaro P, Scrivo R, Valesini G, Perricone R. Emerging role for NK cells in the pathogenesis of inflammatory arthropathies[J]. Autoimmun Rev, 2011, 10:577-581. |

| [3] | Cai Y, Fleming C, Yan J. New insights of T cells in the pathogenesis of psoriasis[J]. Cell Mol Immunol, 2012, 9:302-309. |

| [4] | Telfer N R, Chalmeers R J, Whale L, Colman G. The role of streptococcal infection in the initiation of guttate psoriasis[J]. Arch Dermatol, 1992, 128:39-42. |

| [5] | Prey S, Paul C, Bronsard V, Puzenat E, Gourraud P A, Aractingi S, et al. Assessment of risk of psoriatic arthritis in patients with plaque psoriasis: a systematic review of the literature[J]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2010, 24(Suppl 2):31-35. |

| [6] | Chinmenti M S, Ballanti E, Perricone C, Cipriani P, Giacomelli R, Perricone R. Immunomodulation in psoriatic arthritis: focus on cellular and molecular pathways[J]. Autoimmun Rev, 2013, 12:599-506. |

| [7] | Frisenda S, Perricone C, Valesini G. Cartilage as a target of autoimmunity: a thin layer[J]. Autoimmun Rev, 2013, 12:591-598. |

| [8] | Kane D, Stafford L,Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O. A prospective clinical and radiological study of early psoiatic arthritis: an early synovitis clinic experience[J]. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2003, 42:1460-1468. |

| [9] | Rapp S R, Feldman S R, Exum M L, Fleischer A B Jr, Reboussin D M. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases[J]. J Am Acad Dermatol, 1999, 41:401-407. |

| [10] | Kagami S, Rizzo H L, Lee J J, Koguchi Y, Blauvelt A. Circulating Th17, Th22, and Th1 cells are increased in psoriasis[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2010, 130:1373-1383. |

| [11] | Michalak-Stoma A, Pietrzak A, Szepietowski J C, Zalewska-Janowska A, Paszkowski T, Chodorowska G. Cytokine network in psoriasis revisited[J]. Eur Cytokine Netw, 2011, 22:160-168. |

| [12] | Di Cesare A, Di Meglio P, Nestle F O. The IL-23/th17 axis in the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2009, 129:1339-1350. |

| [13] | Raychaudhuri S R. Role of IL-17 in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis[J]. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol, 2013, 44:183-193. |

| [14] | Eyerich S, Eyerich K, Pennino D, Carbone T, Nasorri F, Pallotta S, et al. Th22 cells represent a distinct human T cell subset involved in epidermal immunity and remodeling[J]. J Clin Invest, 2009, 119:3573-3585. |

| [15] | Sanchez A P. Immunopathogenesis of psoriasis[J]. An Bras Dermatol, 2010, 85:747-749. |

| [16] | Costello P, Bresnihan B, O'Farrelly C, FitzGerald O. Predominance of CD8+T lymphocytes in psoriatic arthritis[J]. J Rheumatol, 1999, 26:1117-1124. |

| [17] | Laloux L, Voisin M C, Allain J, Martin N, Kerboull L, Chevalier X, et al. Immunohistological study of entheses in spondyloarthropathies: comparison in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis[J]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2001, 60:316-321. |

| [18] | Ruderman E M. Evaluation and management of psoriatic arthritis: the role of biologic therapy[J]. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2003, 49:S125-S132. |

| [19] | Fisher V S. Clinical monograph for drug formulary review: systemic agents for psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis[J]. J Manag Care Pharm, 2005, 11:33-55. |

| [20] | Raychaudhuri S P, Raychaudhuri S K, Genovese M C. Phenotypic and functional features of Th-17 cells in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis[J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2008, 58:S352. |

| [21] | Eder L, Chandran V, Pellett F, Pollock R, Shanmugarajah S, Rosen C F, et al. IL13 gene polymorphism is a marker for psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients[J]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2011, 70:1594-1598. |

| [22] | Reich K, Ortonne J P, Gottlieb A B, Terpstra I J, Coteur G, Tasset C, et al. Successful treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with the PEGylated Fab' certolizumab pegol: results of a phase II randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a re-treatment extension[J]. Br J Dermatol, 2012, 167:180-190. |

| [23] | Mease P J, Fleischmann R, Deodhar A A, Wollenhaupt J, Khraishi M, Kielar D, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 24 week results of a phase 3 double blind randomized placebo-controlled study (RAPID-PSA) [J]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2014, 73:48-55. |

| [24] | Reddy M, Davis C, Wong J, Marsters P, Pendley C, Prabhakar U. Modulation of CLA, IL-12R, CD40L, and IL-2Ralpha expression and inhibition of IL-12- and IL-23-induced cytokine secretion by CNTO 1275[J]. Cell Immunol, 2007, 247:1-11. |

| [25] | Leonardi C I, Kimball A B, Papp K A, Yeilding N, Guzzo C, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 76-week results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 1) [J]. Lancet, 2008, 371:1665-1674. |

| [26] | Gottlieb A, Menter A, Mendelsohn A, Shen Y K, Li S, Guzzo C, et al. Ustekinumab, a human interleukin 12/23 monoclonal antibody, for psoriatic arthritis: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial[J]. Lancet, 2009, 373: 633-640. |

| [27] | Cai Y, Shen X, Ding C, Qi C, Li K, Li X, et al. Pivotal role of dermal IL-17-producing γδ T cells in skin inflammation[J]. Immunity, 2011, 35:596-610. |

| [28] | van der Fits L, Mourits S, Voerman J S, Kant M, Boon L, Laman J D, et al. Imiquimodinduced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice is mediated via the IL-23/IL-17 axis[J]. J Immunol, 2009, 182:5836-5845. |

| [29] | Hueber W, Patel D D, Dryja T, Wright A M, Koroleva I, Bruin G, et al. Effects of AIN457, a fully human antibody to interleukin-17A, on psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and uveitis[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2010, 2: 52-72. |

| [30] | McInnes I, Sieper J, Braun J, Emery P, van der Heijde D, Isaacs J, et al. Anti-interleukin 17A monoclonal antibody secukinumab reduces signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis in a 24-week multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2011, 63 (Suppl 10):779. |

| [31] | Rich P, Sirgurgeirsson B, Thaci D, Ortonne J P, Paul C, Schopf R E, et al. Secukinumab induction and maintenance therapy in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase Ⅱ regimen-finding study[J]. Br J Dermatol, 2013, 168:402-411. |

| [32] | Papp K A, Leonardi C, Menter A, Ortonne J P, Krueger J G, Kricorian G, et al. Brodalumab, an anti-interleukin-17-receptor antibody for psoriasis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2012, 366:1181-1189. |

| [33] | Novelli L, Chimenti M S, Chiricozzi A, Perricone R. The new era for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: perspectives and validated strategies[J]. Autoimmun Rev, 2014, 13:64-69. |

| [34] | Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis[J]. Biochem Pharmacol, 2012, 83:1583-1590. |

| [35] | Houslay M D, Schafer P, Zhang K Y. Keynote review: phosphodiesterase-4 as a therapeutic target[J]. Drug Discov Today, 2005, 10:1503-1509. |

| [36] | Claveau D, Chen S L, O'Keefe S, Zaller D M, Styhler A, Lin S, et al. Preferential inhibition of T helper 1, but not T helper 2, cytokines in vitro by L-826,141[4-[2-(3,4-bisdifluromethoxyphenyl)-2-[4-(1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-hydroxypropan-2-yl)-phenyl]-ethyl]3-methylpyridine-1-oxide], a potent and selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor[J]. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2004, 310:752-760. |

| [37] | Eigler A, Siegmund B, Emmerich U, Baumann K H, Hartmann G, Endres S. Anti-inflammatory activities of cAMP-elevating agents: enhancement of IL-10 synthesis and concurrent suppression of TNF production[J]. J Leukoc Biol, 1998, 63:101-107. |

| [38] | Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O'Shea J J. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling[J]. Immunol Rev, 2009, 228:273-287. |

| [39] | Papp K A, Menter A, Strober B, Langley R G, Buonanno M, Wolk R, et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, in the treatment of psoriasis: a phase 2b, randomized, placebo-controlled doseranging study[J]. Br J Dermatol, 2012, 167:668-677. |

| [40] | Gudjonsson J E, Johnston A, Ellis C N. Novel systemic drugs under investigation for the treatment of psoriasis[J]. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2012, 67:139-147. |

| [41] | Schafer P, Parton A, Gandhi A K, Capone L, Adams M, Wu L, et al. Apremilast, a cAMP phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, demonstrates anti-inflammatory activity in vitro and in a model of psoriasis[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2010, 159:842-855. |

| [42] | Schett G, Wollenhaupt J, Papp K, Joos R, Rodrigues J F, Vessey A R, et al. Oral apremilast in the treatment of active psoriatic arthritis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study[J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2012, 64:3156-3167. |

| [43] | Morrow T. First oral medication ok'd to fight psoriatic arthritis[J]. Managed Care, 2014, 23:51-52. |

| [44] | Meyer D M, Jesson M I, Li X, Elrick M M, Funckes-Shippy C L, Warner J D, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity and neutrophil reductions mediated by the JAK1/JAK3 inhibitor, CP-690,550, in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis[J]. J Inflamm (Lond), 2010, 11:7-41. |

| [45] | Fox D A. Kinase inhibition-a new approach to the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2012, 367:565-567. |

| [46] | Quintaás-Cardama A, Vaddi K, Liu P, Manshouri T, Li J, Scherle P A, et al. Preclinical characterization of the selective JAK1/2 inhibitor INCB018424: therapeutic implications for the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms[J]. Blood, 2010, 115:3109-3117. |

| [47] | Punwani N, Scherle P, Flores R, Shi J, Liang J, Yeleswaram S, et al. Preliminary clinical activity of a topical JAK1/2 inhibitor in the treatment of psoriasis[J]. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2012, 67:658-664. |

| [48] | García-Perez M E, Stevanovic T, Poubelle P E. New therapies under development for psoriasis treatment[J]. Curr Opin Pediatr, 2013, 25:480-487. |

| [49] | Mabuchi T, Chang T W, Quinter S, Hwang S T. Chemokine receptors in the pathogenesis and therapy of psoriasis[J]. J Dermatol Sci, 2012, 65:4-11. |

2015, Vol. 36

2015, Vol. 36